Abstract

This study investigates the impact of dermatological diseases on work activity, with a particular focus on potential gender differences. The primary objectives are to evaluate the severity of these conditions and their implications for job performance, productivity, and non-work-related daily activities. A cross-sectional analysis was conducted on employed patients with dermatological conditions between September 2021 and November 2023. Participants completed a new self-reported survey, including the Dermatological Diseases Work Impact Questionnaire (2DWIQ), along with two validated tools: the Work Ability Score (WAS) and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire. Participants were stratified by occupational category (blue- and white-collar workers). Statistical analyses were adjusted for factors influencing questionnaire outcomes, and the internal reliability of the 2DWIQ was assessed using Cronbach’s α. The study included 417 participants (231 men and 186 women) affected by a dermatological disease primarily atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Women reported significantly higher levels of absenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment compared to men. Additionally, they had lower WAS scores, indicating poorer work ability. Dermatological diseases have a greater impact on women, affecting both their work performance and daily lives. Gender-specific interventions are crucial to reducing the physical and psychological burden of these conditions and improving occupational health management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide impact of skin disease is a significant and growing public health challenge. According to the 20191 and 20212 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) studies, dermatosis collectively ranked as the eight leading cause of nonfatal burden globally. These conditions were responsible for 42.9 million DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Years)3, where one DALY equates to 1 year of healthy life lost4. In Europe, prevalence data from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Burden of Skin Disease survey indicates that 43.35% of respondents reported at least one skin disease in the past twelve months, equating to over 185 million adults potentially affected by skin diseases each year5. A European population-based survey estimates that conditions such as alopecia, acne, eczema, and rosacea were more common in women, whereas men were more likely to experience psoriasis and sexually transmitted infections6. Males are generally more commonly afflicted with infectious skin diseases, while women are more susceptible to psychosomatic problems, pigmentary disorders and allergic diseases. The reasons behind these gender differences in skin diseases remain unclear but factors such as skin structure and physiology, sex hormones, ethnicity, cultural behaviors, and environmental influences may all contribute7.

Although skin diseases are often perceived as non-life-threatening, their impact on physical health, quality of life, and economic productivity is profound. Recent studies in dermatology have revealed a multidimensional disease burden that impairs functionality and reduces health-related quality of life, as evidenced in conditions such as atopic dermatitis8. Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis significantly impair quality of life and are frequently associated with psychological comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, and suicidal ideation. Systemic inflammation may represent a biological link between these dermatological and psychiatric conditions9.

The integration of highly effective biological therapies for chronic inflammatory skin disorders has highlighted the need for more precise methods for measuring both direct and indirect costs, including the impact on work productivity, as a key endpoint for evaluating the effectiveness of treatments10,11,12,13,14,15.

The scientific literature underscores the negative effect of dermatological disease on work-related aspects, such as absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work productivity, which result in increased indirect costs. Conditions like hidradenitis suppurativa16, psoriasis17, atopic dermatitis18,19 and chronic urticaria20,21 are particularly implicated.

For instance, Gisondi et al.22 have shown that workers with skin diseases often face career limitations, such as the need to shift their career focus, reject job offers, or the face rejected for desired position, with the highest impact observed in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Additionally, these individuals frequently experience feelings of embarrassment, anxiety, depression, social stigmatization, sleep disruptions, and adverse effects on their professional lives.

Although the impact of dermatological conditions on quality of life and work is well-documented, the specific effects of skin diseases on work activities, particularly from a gendered perspective, remain underexplored in scientific literature. Furthermore, these issues have not yet been thoroughly examined within the field of occupational medicine, which traditionally focuses exclusively on occupational skin diseases. To address these gaps, this study was conducted on a working-age population in Italy to investigate the impact of skin diseases on professional life. Specifically, the study examines how these conditions influence work dynamics, including absenteeism, presenteeism, and the ability to perform work-related tasks across different job categories, with a focus on gender differences. Additionally, the study aims to raise awareness among employers and occupational health physicians regarding the detrimental effects of dermatological conditions on the work capabilities of affected individuals.

Methods

Design and ethics

This cross-sectional analysis is based on data collected from September 2021 until November 2023 at the Department of Dermatology of the University of Pisa. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board named Comitato Etico Regione Toscana—Area Vasta Nord Ovest (Approval number: 24522_FODDIS) and is being performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. All participants included in the study provided written informed consent.

Setting and study population

Eligible subjects were patients over 18 years of age with a dermatological condition who were currently employed. Subjects under the age of 18 were excluded as well as individuals not engaged in work activities. A consecutive recruitment was carried out, and only four eligible patients declined participation, citing time constraints as the reason for non-enrollment.

Occupational medicine physicians worked alongside dermatologists in the following dermatologic specific outpatient clinics, which were accessible to patients either via first-level referrals from community-based primary care providers or through second-level specialist referrals initiated within the hospital setting: General, Psoriasis, Hidradenitis Suppurativa, Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer, Allergology, Acne and Rare Diseases.

Measures

A self-reported survey was developed by the researchers to collect data on the patient’s work situation, their dermatological condition, and how the latter impacts their work activities. It was divided into two sections.

The first section titled “General framework” ( 7 questions) aims to collect gender, age, work sector, job role, job seniority, whether the individual has a recognized occupational dermatological disease, and whether they undergo regular occupational health medical examinations.

During data analysis, based on the chosen work sector, each worker was classified according to the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) occupational classification system23. The classification is the tool used to categorize the various professions in the labor market into specific professional groupings.

A profession is defined as the set of tasks an individual performs within their job, tasks that involve specific knowledge, skills, identity, and status. Professions within the same grouping are those that require the same competencies, both in terms of level and field. The classification system includes five hierarchical levels of aggregation. We used the first level, the highest level of synthesis, that consists of nine major professional groups:

-

1.

Legislators, Entrepreneurs, and Senior Management

-

2.

Intellectual, Scientific, and Highly Specialized Professions

-

3.

Technical Professions

-

4.

Executive Office Workers

-

5.

Skilled Trades in Commercial Activities and Services

-

6.

Craftsmen, Specialized Workers, and Farmers

-

7.

Plant Operators, Machine Operators, and Vehicle Drivers

-

8.

Unskilled Professions

-

9.

Armed Forces

Based on the nine ISTAT groups, participants in the study were subsequently divided into two broad macro-categories: blue-collar workers and white-collar workers24. These terms are commonly used to describe the nature of work and the level of manual versus intellectual labor involved.

The Blue-collar workers group typically refers to individuals engaged in manual labor or skilled trades, often in industrial or physical work environments, such as factory workers, craftsmen, and machine operators. The White-collar workers category includes individuals whose work is primarily intellectual or administrative, often performed in office settings, such as managers, professionals, and clerical staff. This classification helps to better analyze the occupational characteristics and work-related dynamics of the participants of the study.

The second section, titled "Dermatological Condition and Work" (20 questions), aims to collect the following data: diagnosed dermatological diseases, presence or absence of allergies, age at diagnosis, duration of the condition, and most affected body areas. In addition to gathering information about the participant’s dermatological condition, a questionnaire developed by the study’s researchers, the Dermatological Diseases Work Impact Questionnaire (2DWIQ), was administered in this section. This tool assessed the impact of the dermatological condition on work activities. Furthermore, the Work Ability Score (WAS) and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaires were also administered.

Dermatological diseases work impact questionnaire

The 2DWIQ is a tool designed to evaluate the impact of dermatological conditions on an individual’s work and related activities. The questionnaire assesses various factors, including the severity of the condition, its influence on job performance, and its broader effects on workplace interactions and productivity. The 2DWIQ includes 13 items, each addressing a specific aspect of the subject’s work-life and health. These items are scored based on the subject’s responses as showed in Table 1.

The total score is calculated by summing the scores of all items, with each item weighted as described above. The results categorize the impact of the dermatological condition as follows:

-

2–5: Mild impact on work and related activities.

-

6–16: Moderate impact on work and related activities.

-

17–28: Severe impact on work and related activities.

This scoring system enables researchers and clinicians to assess how a dermatological condition affects an individual’s professional life and identify potential areas for intervention. To assess the internal consistency or reliability of the 2DWIQ we chose the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. The Internal consistency evaluates how closely related the items in a questionnaire are as a group. It assumes that all items measure the same underlying trait. This coefficient can assess the consistency of questions designed to evaluate the same construct25,26. The minimum acceptable coefficient was set at 0.627. The internal consistency of 2DWIQ was found to be an acceptable value (α = 0.624), supporting the robustness of the study’s findings.

Work ability score

Work ability refers to an individual’s capacity to perform their work tasks effectively, taking into account their physical, mental, and social resources in relation to the demands of their job. It is a dynamic concept influenced by personal health, skills, work environment, and societal factors28.

The first Work Ability Index (WAI) item ("How would you rate your current work ability compared to your lifetime best?") is often used as an indicator of subjective work ability and it is often called WAS29,30. The WAS is commonly used when a quick assessment of individual’s current ability to work compared to their lifetime best is needed, as it is faster and easier to administer than the full WAI31,32. The individual rates their work ability on a scale from 0 (Completely unable to work) to 10 (Work ability at its lifetime best). Similar to WAI, a WAS score is categorized into four distinct groups: a score of 0 to 5 indicates poor work ability, suggesting that the person may be struggling significantly with their work tasks, possibly due to health or other factors; a score of 6 or 7 reflects moderate work ability, where the person is managing their work but might experience some challenges or limitations; a score of 8 to 9 suggests good work ability, meaning the individual is performing well at work, with only minimal limitations; a score of 10 indicates excellent work ability, showing that the person feels their work ability is at its best, comparable to their peak performance. The WAS and WAI are comparable tools, as they demonstrate similar effectiveness in assessing work ability and its related factors29,30. For this study we used the Italian version of first WAI item corresponding to WAS33,34.

Work productivity and activity impairment

The WPAI is a validated questionnaire designed to assess the impact of general health conditions on work productivity and daily activities during the last 7 days35. Four domains are generated:

-

1.

Absenteeism Time missed from work due to health issues.

-

2.

Presenteeism Reduced productivity while at work due to health problems.

-

3.

Overall Work Impairment (OWI) Combines absenteeism and presenteeism to provide a total productivity impairment score.

-

4.

Activity Impairment (AI) Impact of health issues on non-work-related daily activities.

WPAI outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages. Higher WPAI scores indicate greater impairment and less productivity36. If the dermatological condition for which the patient was evaluated was psoriasis, chronic urticaria, or melanoma, we used the specific Italian version of the WPAI: WPAI:PSO (Italian-Italy, v2.0), WPAI:CU (Italian-Italy, v2.3), or WPAI: Melanoma (Italian-Switzerland, v2.1), respectively37. For other dermatological conditions we used the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem (WPAI:SHP)38. We adapted the WPAI:SHP to a specific dermatological disease replacing “problem” throughout with the name of the skin condition for which the patient was seen by the dermatology colleagues. For the Italian version we used the template created for other diseases37.

Administration of the survey

At the end of the physical examination conducted by the dermatologists, the subject’s current employment status and age were inquired about. If the responses met the study’s inclusion criteria, participation in the study was proposed, and the objectives of the questionnaire were explained. After obtaining the signed consent, a tablet was provided to the patient, allowing them to access the questionnaire created using the Microsoft Office Forms platform. Completing the survey, 2DWIQ, WAS and WPAI took approximately 15 min.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, the sample size was determined based on the calculation of the effect size for the results of the WAS. We estimated that a difference of 1 unit between males and females, with SD = 3, should be statistically significant (p value 5%, power 90%). Under these conditions, the aforementioned effect size will require the enrollment of 400 subjects to achieve statistical significance. Continuous data were summarized with mean and standard deviation. Continuous and categorical factors influencing questionnaire outcomes were compared with gender using t-test for independent samples and chi square test, respectively. Successively, to compare the questionnaire outcomes with gender together with factors significant to the univariate tests multiple linear regressions as multivariate analyzes were performed and autocorrelation was also assessed calculating Durbin-Watson statistic.

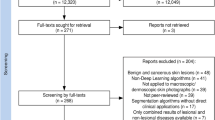

Results

In accordance with the effect size, the study population consists of 231 men (mean age 45.9 years ± 11.40) and 186 women (mean age 43.87 ± 12.05). It can be observed in Table 2 that the most commonly reported skin disease was psoriasis (141 males, 91 females), followed by atopic dermatitis (33 males, 27 females) and hidradenitis suppurativa (18 males, 15 females).

Regarding disease localization, 114 subjects reported involvement exclusively in the upper body (head/neck/trunk/back/upper limbs), 66 in the lower body (sacral/genital/lower limbs), and 237 in both areas. Specifically, the hand region was affected in 36.45% of the sample (152 subjects) and the face in 20.62% (86 subjects). In addition, 84 women and 67 men reported a previous diagnosis of allergic diathesis.

Regarding the occupational history, in this study manual and non-manual workers were distinguished based on the type of tasks performed: 153 men and 107 women perform jobs in the blue-collar category (non-office workers), while 78 men and 79 women belong to the white-collar category (non-manual workers). In the white-collar category, the most represented job for both men and women is office clerk (n = 46, 59% M; n = 39, 49% F). In the blue-collar category, the most common occupation for men is skilled tradesman/craft worker (n = 63, 41%), while for women, it is a sales/services sector worker (n = 41, 38%).

As showed in Tables 2 and 3, the male and female groups were homogeneous in terms of age, duration of dermatological disease and distribution by work role. However, factors influencing questionnaire outcomes included the average seniority in the job (M 17.25 years ± 12.48; F 13.68 years ± 11.11, p = 0.002) and, among the recorded types of diseases, to suffer from psoriasis (more associated with males, p = 0.013), lichen (more associated with females, p = 0.028) and seborrheic dermatitis (more associated with males, p = 0.24).

Table 4 shows the linear regression models for the different questionnaires, where the results have been standardized to eliminate the aforementioned continuous and categorical factors influencing questionnaire outcomes. Of all the factors influencing questionnaire outcomes, sex was the only variable that significantly influenced the outcome of 2DWIQ (M mean 8.42 DS 4.64; F mean 9.72 DS 4.04) and WPAI in terms of absenteeism (M mean 1% DS 5%; F mean 5% DS 16%), OWI (M mean 8% DS 16%; F mean 14% DS 24%), and AI (M mean 12% DS 24%; F mean 20% DS 29%). WAS is the only outcome influenced by both gender (M mean 7.44 DS 2.49; F mean 6.89 DS 2.61) and job seniority.

Multivariate analysis revealed that being female is associated with higher average scores for 2DWIQ (p = 0.030), Absenteeism (p = 0.006), OWI (p = 0.006), and AI (p = 0.004). However, the difference in average presenteeism values between the two sexes was not statistically significant (M mean 6% DS 15%; F mean 9% DS 18%; p > 0.05).

All the multivariate analyzes showed Durbin-Watson statistic near 2 indicating autocorrelation absence.

Finally, being female was significantly associated with lower WAS values compared to males (p = 0.012).

Discussion

To date, numerous studies in occupational medicine focus on the causal relationship between dermatological conditions and work activities, particularly allergic and irritant dermatitis39,40,41,42.

However, evidence on the inverse relationship—how dermatological conditions affect work life—remains limited, especially beyond their impact on productivity, with few studies examining how these conditions alter work activities and whether these changes differ by sex43,44.

To assess the gender-specific repercussions of dermatological diseases on work activity, two validated questionnaires (WPAI and WAS) were administered, along with the newly developed 2DWIQ, which investigates both occupational and non-occupational aspects of daily life.

The study accounted for factors influencing questionnaire outcomes, including job seniority and disease type, by employing standardized linear regression models. While sex remained the most influential variable, it is worth noting that psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and lichen exhibited differing associations with males and females, emphasizing the need for tailored work-related accommodation based on disease type and patient characteristics.

The observed population exhibited equal gender distribution in the most dermatological diseases, except for psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and lichen. These conditions were more commonly associated with males (psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis) and females (lichen), respectively. These findings align with existing literature for lichen and seborrheic dermatitis, but not for psoriasis. In fact, some studies reported a higher incidence of psoriasis in women than in men, whereas other studies presented contrasting results6,45,46,47.

Regarding occupational history, the recruited male and female workers were equally distributed within white-collar and blue-collar roles. In Tuscany, ISTAT 2022 data highlights that the industrial sector is predominantly composed of male workers, while the service sector tends to include more women48. That supports the observed trend in our study, where men were more likely to be employed as skilled tradesmen/craft workers, and women were more represented in sales and services roles.

The results reveal that women reported significantly higher scores for absenteeism, OWI, and AI compared to men. Despite this, dermatological conditions appeared to impact non-work activities slightly more than work-related ones for both sexes. Notably, in the non-work context, women reached significantly higher negative impact values (≥ 20%).

WAS analysis showed that both sexes had moderate work ability relative to their lifetime best. However, women reported lower WAS scores, positioning them in the lower half of the moderate range (better classified as poor-to-moderate), while men reported scores in the upper half (moderate-to-good). These results parallel the findings of the 2DWIQ, which also demonstrated a “moderate impact” of dermatological disease on work activities, with significantly higher scores among women. Female respondents reported scores more than one point higher on average than their male counterparts, particularly in domains related to work discomfort, sleep disturbances and general health assessment.

These findings suggest that the cumulative burden of dermatological diseases on woman life has a greater impact than man beyond their professional roles49,50.

Women often experience greater psychological and functional impairment due to chronic dermatological conditions, driven by heightened emotional distress, body image concerns, and societal pressure49.

Chronic inflammatory diseases are particularly noteworthy in this context, as they are often associated with multiple comorbidities that collectively contribute to a significant decline in patients’ quality of life. The assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has become an essential component in the evaluation of clinical endpoints, as it provides valuable insights that can inform therapeutic optimization, enhance symptom control, and improve the overall continuum of care 51. The deterioration in quality of life among dermatological patients is largely influenced by disease-specific factors such as anatomical location and severity, in addition to the presence of comorbidities. Psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa are paradigmatic examples of this clinical scenario52,53,54.

From a gender perspective, hidradenitis suppurativa represents the dermatological condition most profoundly associated with impaired quality of life, particularly among female patients. In women, the various phases of life are characterized by physiological fluctuations in hormone levels, which may further exacerbate disease burden and psychosocial impact54. Emotional stress, psychosocial burden, and psychiatric comorbidities are additional factors contributing to the complex clinical profile of dermatological patients experiencing reduced quality of life. Besides psoriasis52 and hidradenitis suppurativa54, other notable examples include atopic dermatitis55,56, rosacea57, and alopecia areata58.

Furthermore, studies indicate that skin diseases such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis have a more significant impact on women’s quality of life and work-related functioning, particularly in roles requiring frequent social interaction. This heightened impact may be explained also by the large burden of unpaid caregiving and household responsibilities often shouldered by women59,60,61,62, which worsens psychological stress and exposure to sensitizing chemicals. Indeed, it has been observed that factors such as the higher prevalence of allergic and psychosomatic conditions in women, likely contribute to these disparities63,64,65.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, its cross-sectional design and the absence of a control group does not allow for the establishment of causal relationships between dermatological diseases and their impact on work-related activities.

Second, the study is monocentric, conducted at a single university center that serves as a referral point for chronic inflammatory skin diseases in Tuscany. In our study, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa emerged as the most represented conditions. The possibility of selection bias cannot be excluded, and consequently, the sample may not fully represent the entire spectrum of dermatological conditions.

Another important limitation is the inclusion criterion requiring current employment, which may have introduced a second selection bias. This criterion excluded all individuals who were not employed at the time of the study, regardless of the reason. However, this does not result in an underestimation of absenteeism and presenteeism, since these outcomes are inherently measured only among currently employed individuals, in line with their definition and standard methods of assessment. Notably, 19 participants in our sample reported having changed jobs in the past due to their dermatological condition, further highlighting the broader professional impact of these diseases.

Moreover, most patients in this study were undergoing biologic therapies, which likely contributed to low or moderate disease severity scores. This may have underestimated the true burden of disease, as individuals with more severe, untreated conditions might experience a greater impact on work and daily functioning. Additionally, the study did not account for potential factors influencing questionnaire outcomes, such as comorbid mental health conditions or socioeconomic status, which could further influence work-related outcomes. In this regard, further studies are warranted to investigate the impact of factors known in the literature, but not addressed in the present study, on work-related activity. Such factors include disease-specific severity scores and the type of treatment administered.

Finally, the study provides only an instant capture of patients’ health status and work-related impact, as the questionnaires (2DWIQ, WAS, and WPAI) were administered at a single time point. This limits the ability to assess longitudinal changes, fluctuations in disease activity, and their evolving impact on work productivity.

Conclusion

This study highlights notable sex-based differences in the impact of dermatological diseases on work and daily life outcomes. Women reported higher levels of disease-related absenteeism, work impairment, and activity impairment, along with lower work ability scores compared to men.

Our research contributes to the limited body of literature addressing the occupational impact of dermatological conditions from a gender perspective. While previous studies have primarily focused on occupational skin diseases or treatment efficacy, this study expands the scope by exploring the broader effects of dermatological diseases on work performance and quality of life in a diverse blue- and white-collar workforce. The use of validated tools such as WAS and WPAI, along with the novel 2DWIQ, provides a multidimensional framework for assessment.

These findings emphasize the need for increased awareness among employers and occupational health professionals about the burden of dermatological diseases. Future research should focus on developing and evaluating such interventions to foster supportive and gender equitable work environments for individuals affected by dermatological diseases.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the presence of information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yakupu, A. et al. The burden of skin and subcutaneous diseases: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front. Public Health 11, 1145513. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1145513 (2023).

Ferrari, A. J. et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 403(10440), 2133–2161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 (2024).

Global Health Metrics Skin and subcutaneous diseases—Level 2 cause https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-skin-and-subcutaneous-diseases-level-2, accessed 7 September 2024 (2021)

Murray, C. J. et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 380(9859), 2197–2223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 (2012).

Trakatelli, M. et al. The burden of skin disease in Europe. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 37(Suppl 7), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.19390 (2023).

Richard, M. A. et al. Prevalence of most common skin diseases in Europe: A population-based study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 36(7), 1088–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18050 (2022).

Chen, W., Mempel, M., Traidl-Hofmann, C., Al Khusaei, S. & Ring, J. Gender aspects in skin diseases. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 24(12), 1378–1385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03668.x (2010).

Argenziano, G. et al. Burden of disease in the real-life setting of patients with atopic dermatitis: Italian data from the MEASURE-AD study. Dermatol. Pract. Concep. 14(1), e2024079 (2024).

Balato, A. et al. The impact of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis on quality of life: A literature research on biomarkers. Life Basel 12(12), 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12122026 (2022).

Finlay, A. Y. The burden of skin disease: Quality of life, economic aspects and social issues. Clin. Med. 9(6), 592 (2009).

Bickers, D. R. et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004: A joint project of the American academy of dermatology association and the society for investigative dermatology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 55(3), 490–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048 (2006).

Kimball, A. B. et al. The effects of adalimumab treatment and psoriasis severity on self-reported work productivity and activity impairment for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 66(2), e67-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.10.020 (2012).

Armstrong, A. W. et al. Effect of Ixekizumab treatment on work productivity for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: Analysis of results from 3 randomized phase 3 clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 152(6), 661–669. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0269 (2016).

Warren, R. B. et al. Secukinumab significantly reduces psoriasis-related work impairment and indirect costs compared with ustekinumab and etanercept in the United Kingdom. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 32(12), 2178–2184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15094 (2018).

Saeki, H. et al. Work productivity in real-life employed patients with plaque psoriasis: Results from the ProLOGUE study. J. Dermatol. 49(10), 970–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.16517 (2022).

Schneider-Burrus, S. et al. The impact of hidradenitis suppurativa on professional life. Br. J. Dermatol. 188(1), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljac027 (2023).

Villacorta, R. et al. A multinational assessment of work-related productivity loss and indirect costs from a survey of patients with psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 183(3), 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.18798 (2020).

Andersen, L., Nyeland, M. E. & Nyberg, F. Increasing severity of atopic dermatitis is associated with a negative impact on work productivity among adults with atopic dermatitis in France, Germany the UK and the USA. Br. J. Dermatol. 182(4), 1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.18296 (2020).

Eckert, L. et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: An analysis using the national health and wellness survey. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 77(2), 274-279.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.019 (2017).

Vietri, J. et al. Effect of chronic urticaria on US patients: Analysis of the national health and wellness survey. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 115(4), 306–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2015.06.030 (2015).

Staubach, P. et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic urticaria is differentially impaired and determined by psychiatric comorbidity. Br. J. Dermatol. 154(2), 294–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06976 (2006).

Gisondi, P. et al. Quality of life and stigmatization in people with skin diseases in Europe: A large survey from the burden of skin diseases EADV project. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 37(7), 6–14 (2023).

ISTAT Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Classificazione delle professioni https://www.istat.it/classificazione/classificazione-delle-professioni, accessed 10 November 2024 (2023)

Lips-Wiersma, M., Wright, S. & Dik, B. Meaningful work: Differences among blue-, pink-, and white-collar occupations. Career Dev. Int. 21(5), 534–551. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-04-2016-0052 (2016).

Sijtsma, K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika 74(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0 (2009).

McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychol. Methods 23(3), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144 (2018).

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Babin, B. & Black, W. Data Analysis 7th edn. (Pearson New International, 2013).

Ilmarinen, J. Work ability-a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 35(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.130 (2009).

El Fassi, M. et al. Work ability assessment in a worker population: Comparison and determinants of work ability index and work ability score. BMC Public Health 13, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-305 (2013).

Mokarami, H., Cousins, R. & Kalteh, H. O. Comparison of the work ability index and the work ability score for predicting health-related quality of life. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 95(1), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01740-9 (2022).

Mokarami, H., Mortazavi, S. B., Asgari, A. & Choobineh, A. Work ability score (WAS) as a suitable instrument to assess work ability among Iranian workers. Health Scope 6(1), e42014. https://doi.org/10.17795/jhealthscope-42014 (2017).

Ebener, M. & Hasselhorn, H. M. Validation of short measures of work ability for research and employee surveys. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(18), 3386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183386 (2019).

Costa, G., Goedhard, W. & Ilmarinen, J. Assessment and Promotion of Work Ability, Health and Well-Being of Ageing Workers (Elsevier, 2005).

Costa, G. & Sartori, S. Ageing, working hours and work ability. Ergonomics 50(11), 1914–1930. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130701676054.783632316 (2007).

Reilly, M. C., Zbrozek, A. S. & Dukes, E. M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 5, 353–365. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006 (1993).

Reilly Associates WPAI Scoring http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_Scoring.html, accessed 12 November 2024 (2002)

Reilly Associates WPAI Translation http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_Translations.html, accessed 12 Novembre 2024 (2002)

Reilly Associates WPAI:SHP V2.0 http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_SHP.html, accessed 12 Novembre 2024 (2002)

Murshid, M. L. et al. Exploring the effect of occupational dermatitis at the workplace: A literature review. J. Sci. Manag. Res. 14(2), 2600–2738 (2024).

Fowler, J. et al. Impact of chronic hand dermatitis on quality of life, work productivity, activity impairment, and medical costs. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 54(3), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1053 (2006).

Kalboussi, H. et al. Impact of allergic contact dermatitis on the quality of life and work productivity. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 3(2019), 3797536. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3797536 (2019).

Raulf, M., Brüning, T., Jensen-Jarolim, E. & van Kampen, V. Gender-related aspects in occupational allergies—secondary publication and update. World Allergy Organ J. 10(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40413-017-0175-y (2017).

Nørreslet, L. B., Ebbehøj, N. E., Ellekilde Bonde, J. P., Thomsen, S. F. & Agner, T. The impact of atopic dermatitis on work life—a systematic review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 32(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14523 (2018).

Wu, Y., Mills, D. & Bala, M. Impact of psoriasis on patients’ work and productivity: a retrospective, matched case-control analysis. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 10(6), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.2165/11310440-000000000-00000 (2009).

Zander, N. et al. Epidemiology and dermatological comorbidity of seborrhoeic dermatitis: Population-based study in 161 269 employees. Br. J. Dermatol. 181(4), 743–748. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17826 (2019).

Kyriakis, K. P. et al. Sex and age distribution of patients with lichen planus. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 20(5), 625–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01513.x (2006).

Parisi, R. et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: Systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ 369, m1590. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1590 (2020).

Occupazione e disoccupazione in Toscana: dati 2022 https://www.regione.toscana.it/-/occupazione-e-disoccupazione-in-toscana-dati-2022, accessed 16 Novembre 2023 (2022)

Lagacé, F. et al. The role of sex and gender in dermatology—from pathogenesis to clinical implications. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 27(4), NP1–NP36. https://doi.org/10.1177/12034754231177582 (2023).

Hassanin, A. M., Ismail, N. N., El Guindi, A. & Sowailam, H. A. The emotional burden of chronic skin disease dominates physical factors among women, adversely affecting quality of life and sexual function. J. Psychosom. Res. 115, 53–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.10.011 (2018).

Haraldstad K et al. LIVSFORSK network. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. ;28(10):2641–2650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9.(2019)

Scala, E., Kaczmarczyk, R., Zink, A. & Balato, A. Sociodemographic, clinical and therapeutic factors as predictors of life quality impairment in psoriasis: A cross-sectional study in Italy. Dermatol. Ther. 35(8), e15622. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15622 (2022).

Armstrong, A. W. et al. Patient perspectives on psoriatic disease burden: Results from the global psoriasis and beyond survey. Dermatology 239(4), 621–634. https://doi.org/10.1159/000528945 (2023).

Dattolo, A. et al. Beyond the skin: Endocrine, psychological and nutritional aspects in women with hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Transl. Med. 23(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-06175-1 (2025).

Courtney, A. & Su, J. C. The psychology of atopic dermatitis. J. Clin. Med. 13(6), 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061602 (2024).

Gonzalez-Uribe, V., Vidaurri-de la Cruz, H., Gomez-Nuñez, A., Leyva-Calderon, J. A. & Mojica-Gonzalez, Z. S. Comorbidities and burden of disease in atopic dermatitis. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 41(2), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.12932/AP-231022-1484 (2023).

Chiu, C. W., Tsai, J. & Huang, Y. C. Health-related quality of life of patients with Rosacea: A systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world data. Acta Derm. Venereol. 104, adv40053. https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.40053 (2024).

Toussi, A., Barton, V. R., Le, S. T., Agbai, O. N. & Kiuru, M. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: A systematic review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 85(1), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.047 (2021).

Alya, A., Saleh, A., Sawsan, A. & Louai, S. Psychosocial implications and quality of life in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa compared to those with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: A cross-sectional case-control study. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 13(2), e2023076. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.1302a76 (2023).

Sampogna, F., Tabolli, S., Abeni, D., IDI Multipurpose Psoriasis Research on Vital Experiences (IMPROVE) investigators. Living with psoriasis: Prevalence of shame, anger, worry, and problems in daily activities and social life. Acta Derm. Venereol. 92(3), 299–303. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1273 (2012).

Colombo, D., Cassano, N., Bellia, G. & Vena, G. A. Gender medicine and psoriasis. World J. Dermatol. 3(3), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.5314/wjd.v3.i3.36 (2014).

EU-OSHA report. Gender aspects of safety and health at work—A summary. https://osha.europa.eu/de/tools-and-publications/publications/reports/209, accessed 18 December 2024 (2006)

Chorna, N, Psychosomatic aspects of women’s health. An in-depth analysis https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4747275 (2024)

Pali-Schöll, I. & Jensen-Jarolim, E. Gender aspects in food allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 19(3), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACI.0000000000000529 (2019).

Jensen-Jarolim, E. Gender effects in allergology–secondary publications and update. World Allergy Organ. J. 10(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40413-017-0178-8 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to extend their heartfelt gratitude to the resident physicians from the School of Occupational Medicine of University of Pisa for their contribution to the data collection. The authors also express their appreciation to the resident and specialist physicians of the Dermatology Department of University of Pisa.

Funding

This research receives no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Martina Padovan contributed to conceptualization, methodology, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data collection, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing- review and editing. Bianca Benedetta Benincasa contributed to methodology, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data collection, formal analysis. writing-original draft, writing- review and editing. Salvatore Panduri contributed to data collection, supervision, project administration. Valentina Dini contributed to supervision, project administration. Riccardo Morganti contributed to formal analysis and visualization. Riccardo Marino contributed to supervision, project administration. Poupak Fallahi contributed to editing, Marco Romanelli contributed to supervision, project administration. Rudy Foddis contributed to methodology, definition of intellectual content, supervision, project administration, writing-original draft, writing- review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board: Comitato Etico Regione Toscana—Area Vasta Nord Ovest (24522_FODDIS, 12 September 2023). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Padovan, M., Benincasa, B.B., Panduri, S. et al. Assessing the burden of dermatological diseases on work life from a gender perspective. Sci Rep 15, 24014 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07804-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07804-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Quality of life and patient satisfaction among individuals with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Syria: a cross-sectional study

Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2026)