Abstract

This study presents an investigation into enhancing heat transfer in parabolic trough collectors (PTCs). The research focuses on improving convective heat transfer by incorporating longitudinal fins within the tubular absorber of a PTC. The study examines a PTC (parabolic trough collector) system with the following specifications: a 1.84 m focal length, a 5 m aperture width, and an absorber measuring 70 mm in outer diameter. The variable solar flux on the absorber is determined using SolTrace software. The receiver was simulated using the finite volume method. The heat flux derived from SolTrace simulations serves as a boundary condition. A comparative analysis is conducted between the findings from a parametric investigation on a standard receiver and those equipped with finned tubular absorbers. This comparison spans Reynolds numbers from 0.25 × 105 to 2.82 × 105. Studies have demonstrated that absorbers with fins substantially improve heat transfer. The tubular absorber equipped with fins shows a significant rise of 40.1% in the Nusselt number. Its performance evaluation criteria reach a peak of 1.28 when the Reynolds number is 2.82 × 105.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solar power generation at an industrial scale is achieved through technology utilizing parabolic trough collectors (PTC)1,2,3. Over the last several decades, numerous researchers have conducted a variety of numerical and experimental investigations aimed at enhancing the performance of the PTC4. These investigations focused on enhancing various aspects, including design, thermal efficiency of receivers, performance of selective coatings, advancements in optical error measurement techniques, and the effectiveness of working fluids.

A significant challenge in PTC systems is enhancing the thermal energy transfer from the absorbing component to the fluid responsible for heat transport5. Improving the rate at which heat is transferred to the heat transfer fluid (HTF) boosts the thermal output of each receiver component, resulting in a decrease in the overall number of receiver components needed. The utilization of fewer receiver components reduces both setup and operational costs, thereby enhancing the overall cost-effectiveness of the PTC system. Increasing the fluid’s contact area improves heat transmission in the absorber. Incorporating fins into the absorber is considered an effective method for expanding the fluid contact surface and thereby improving heat transfer efficiency. In PTCs, both passive and active heat transfer methods are utilized to enhance efficiency. Passive methods, such as conduction and radiation, occur naturally within the receiver, wherein solar radiation heats the working fluid. Nevertheless, active methodologies such as forced convection are frequently utilized, wherein pumps circulate heat transfer fluids (HTFs) through the system to facilitate more efficient heat transport. This combination facilitates effective heat collection and transfer for energy applications, thereby optimizing the overall performance of the PTC system. While both passive and active techniques exist, the passive approach is more commonly adopted. Active heat transfer methods, such as forced convection, increase costs due to energy consumption and maintenance requirements but enhance efficiency in PTCs. Passive methods, such as fins or geometric optimization, are more cost-effective initially but may provide limited efficiency improvements, rendering a combination of both approaches a potentially economical solution. However, the integration of fins within the absorber may result in increased pressure drop, potentially necessitating additional pumping power. Thus, this approach represents a combination of both aforementioned strategies. As a result, it is crucial to evaluate both the heat transfer characteristics and pressure loss in a finned receiver.

One passive technique for enhancing heat transfer involves improving the heat absorption of the heat transfer fluid (HTF) by applying specialized coatings composed of materials with high absorptivity and low emissivity on the outer surface of the absorber6.Recent research has explored the use of nanofluids as a heat transfer fluid to augment thermal transfer within the absorber. Talem et al. conducted an investigation into the performance of parabolic trough solar collectors (PTSC) utilizing Dowtherm A oil-based nanofluids containing Pd, Au, and NiO nanoparticles. The principal findings of the study reveal that the Au-based nanofluid achieved the highest outlet temperature, with a maximum increase of approximately 8%7.

Panja et al. analyzed the thermal performance of PTSCs using porous inserts and nanofluids. Their results demonstrate an enhancement in thermal efficiency, with an increase of 7.73% for Al₂O₃ nanofluids and 8.59% for CuO nanofluids. While nanofluids exhibit improved thermal performance, they are associated with several limitations. The production of these materials is costly, and they face stability challenges due to the agglomeration of nanoparticles, which can lead to sedimentation and reduced efficiency. Increased viscosity necessitates greater pumping power, and the presence of nanoparticles may cause erosion and corrosion in system components. Furthermore, the substantial preparation costs and the requirement for high-quality equipment render the current use of nanofluids economically impractical8.

Furthermore, the rate of heat absorption by the HTF can be enhanced by either increasing the heat transfer efficiency within the absorber or by minimizing heat loss from the absorber9. This study examines the improvement of the heat absorption rate of the HTF through the optimization of heat transfer efficiency within the absorber. A substantial body of existing research has concentrated on augmenting heat transfer within the absorber10. Various techniques have been proposed in the literature, including the use of nanofluids, alterations to absorber tube geometries, and the implementation of diverse flow inserts to enhance heat transfer within the absorber.

Research has previously explored the use of fins to improve heat transfer rates in absorbers. Reddy, Kumar5 conducted a study examining the heat transfer properties of PTC receivers incorporating longitudinal porous fins. These fins were integrated along the entire inner circumference of the absorber. Their findings revealed that the introduction of porous fins to the receiver led to a 17.5% increase in heat transfer, accompanied by a 2 kPa pressure drop. Reddy and Satyanarayana9 carried out a numerical simulation of a PTC receiver by using trapezoidal porous inserts inside the absorber and about 13.8% improvement in the heat transfer with 1.7 kPa pressure penalty has been reported. Muñoz and Abánades11 have utilized helically finned absorbers for the PTC to improve internal heat transmission. It was stated that the total performance of a 20 MWe power plant might be improved by up to 2%. To improve heat transfer, Cheng, He12 implemented vortex generators in the absorber’s lower section. The alteration resulted in a peak improvement of 1.14 in the assessment criteria. Amina, Miloud13 studied the performance of the PTC by using longitudinal fins and nanofluids. Simulations have been carried out for the Reynolds number ranging from 2.57 × 104 to 2.57 × 105 with an operating temperature of 573 K. Studies have shown that the Nusselt number experienced an increase ranging from 1.3 to 1.8 times. Bellos, Tzivanidis14 examined the thermal efficiency of the PTC by incorporating longitudinal fins within the absorber. Various fin dimensions were evaluated using carbon dioxide, helium, and air as working fluids. The study concluded that a 10 mm fin demonstrated the highest exergetic efficiency. A study conducted by Bellos, Tzivanidis15 examined the efficiency of the LS2 collector using various sizes of longitudinal fins within the absorber, with syltherm800 as the working fluid. Their findings revealed that an absorber with dimensions of 2 mm thickness and 10 mm length yielded the best results, leading to a 0.82% improvement in thermal efficiency. Bellos, Tzivanidis15,16 studied the performance of the LS2 collector by analyzing the longitudinal fins of various lengths and thicknesses with syltherm800 as the working fluid. It was determined that a fin with dimensions of 4 mm in length and 20 mm in thickness increased thermal efficiency by 1.27%. Gong, Wang17 conducted a computational study to evaluate the effectiveness of internal pin fin arrays in enhancing heat transfer within a PTC receiver. The findings of their investigation demonstrated that the heat transfer performance factor exhibited an increase of 12%, while the average Nusselt number showed an increase of 9%. Bellos, Tzivanidis18 carried out the numerical simulation of the PTC receiver by employing various numbers of rectangular longitudinal fins inside the absorber. Around 0.51% improvement in thermal efficiency has been reported for the case of an absorber with three fins placed at the lower portion of the absorber. The studies5,17 indicate that while pin fins can improve heat transfer, they also cause a substantial increase in pressure drop. Efficiency may be enhanced by placing fins at the absorber’s maximum solar radiation points, as this could increase the effective area for heat transfer18. To evaluate the improvement in heat transfer and the associated decrease in pressure, a thorough thermal analysis must be performed. Several studies have focused on enhancing heat transfer in solar collectors using passive techniques such as wire-coils, twisted tapes, metal foams, and nanofluids. Abu-Hamdeh et al. (2020) investigated the impact of internal rectangular ribs on curved absorber tubes in cylindrical solar collectors. Their numerical analysis showed that ribbed configurations, especially on the upper side, significantly improved thermal performance—enhancing heat absorption by up to 47.7% with an overall performance increase of 120%19. Farnam and Khoshvaght-Aliabadi (2022) conducted a detailed numerical and experimental study on twisted absorber tubes for solar collectors. By analyzing various twisted structures—including combinations of twisted tubes and inserts—they found significant improvements in thermal performance, with Nusselt number enhancement up to 3.72 times and energy efficiency reaching 90.4%20.

Various studies have explored innovative methods to enhance the performance of PTC systems, such as helical rotating shaft inserts, corrugated tube receivers with conical strip inserts, helical screw tape inserts, and integrated helical coil heat exchangers. Allam et al.21 have conducted an experimental investigation into the performance of a PTC utilizing a helical rotating shaft insert within the absorber. The researchers have reported a significant improvement in the performance of the PTC, with a rotational shaft speed of 21 RPM and a flow rate of 1 LPM resulting in a 37% enhancement in thermal efficiency. Ramalingam Venkatesaperumal. R. et al.22. have investigated the enhancement of PTC performance through increased heat transfer, utilizing a corrugated tube receiver with conical strip inserts. In the study of corrugated tube receivers with conical strip inserts, researchers reported a 177% enhancement in the Nusselt number, a 38% increase in the friction factor, and a 9% improvement in thermal efficiency. Roohi, R. et al.23. conducted a numerical study on the performance enhancement of the PTC utilizing helical screw tape inserts. The research findings indicate that the Performance Evaluation Criterion (PEC) exhibited an improvement of up to 105.9%. Said, S. et al.24 introduced an innovative evacuated tube solar collector (ETSC) integrated with a helical coil heat exchanger to enhance the performance of the PTC for domestic water heating. Through this novel design, the researchers achieved a higher thermal efficiency of 72%. Limboonruang, T. et al.25. investigated the enhancement of heat transfer and thermal efficiency through the utilization of external fins. They reported a substantial improvement in the thermal performance of the PTC with external fins. These approaches have demonstrated significant improvements in thermal efficiency and heat transfer capabilities, marking promising advancements in solar thermal technology. Golzar et al. have conducted an investigation into the performance of the PTSC, employing a novel geometric design characterized by an elliptical absorber tube under the influence of a magnetic field. The findings suggest that the integration of an elliptical cross-section in the PTSC substantially enhances thermal efficiency. The impact of the magnetic field on the elliptical absorber tube is shown to improve hydrodynamic performance, achieving the highest exergy efficiency across the tested Reynolds numbers and parameters26. Donga et al. evaluated the PTC using a rhombus-shaped absorber tube, discovering a maximum increase of 1.4% in overall efficiency, 1.45% in exergy efficiency, and 2.88% in thermal efficiency compared to the traditional circular absorber27. Furthermore, Donga et al. examined the performance of the PTC with cylindrical attachments of radii 5, 10, 15, and 20 mm, reporting that the modified PTC with 20 mm cylindrical attachments exhibited increases in thermal efficiency and overall efficiency of up to 1.18% and 1.05%, respectively, at an inlet temperature of 650 K28.

Two approaches for examining the heat transfer capabilities of PTC receivers have been elaborated on in recent years29,30. One of the methods suggested was to consider the homogeneous heat flow over the surface of the absorber while conducting the heat transfer analysis of the PTC receiver30,31. Because the heat flux distribution over the absorber is non-uniform in real situations, the results of this research may not be applicable to outside conditions. Another approach is to consider the varying heat flux on the absorber’s outer surface5,32 for conducting heat transfer analysis in the PTC receiver. Adopting this approach would necessitate performing a separate optical examination of the PTC to determine the heat flux distribution over the absorber. The thermal analysis makes use of the optical simulation-obtained heat flux as a boundary condition. Numerous analytical and computational strategies for determining the heat flux distribution over the absorber have been presented33,34,35. Out of various available techniques, the Monte Carlo Ray Tracing (MCRT) method is widely preferred due to its superior convenience and accuracy5,32,35,36,37,38,39,40. The heat transfer in the PTC receiver has been examined by Cheng, He38,39 through the integration of MCRT and FVM. Their findings aligned with the experimental outcomes of Dudley, Kolb41demonstrating a mean relative deviation in the PTC efficiency of less than ± 2%. Thereafter, numerous researchers have employed a comparable approach to investigate heat transfer in PTC receivers32,36,37,39,42,43,44,45.

The aim of this research is to enhance the performance of the parabolic trough collector (PTC) by increasing the heat absorption of the heat transfer fluid (HTF) through an improved heat transfer rate within the absorber, achieved by incorporating fins. This study employs longitudinal fins with triangular and rectangular cross-sections within the absorber of the PTC to augment heat transfer. The concentrated solar power is directed to the receiver’s lower section, indicating that the strategic placement of fins in this area could potentially enhance heat transfer, thereby increasing the heat absorption of the HTF. Consequently, in this study, fins are positioned at the lower portion of the absorber. To examine this hypothesis, the study employs a numerical simulation utilizing a combination of Monte Carlo Ray Tracing (MCRT) and finite volume method (FVM) techniques. The LS 2 collector considered in the study of is considered for the analysis.

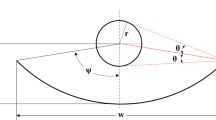

PTC geometry

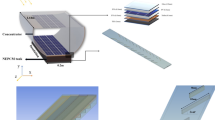

The fundamental components of the PTC system, namely the cylindrical parabolic reflector and the receiver assembly, are depicted in Fig. 1. The sun rays incident on the mirror are concentrated on a receiver situated at the focal line of a parabolic reflector. In the receiver assembly, a metal tubular absorber is encased in a glass cover to allow concentrated rays to reach the absorber. To reduce convective losses, the area between the tubular absorber and the glass cover is evacuated. At the absorber, the energy of the incident concentrated ray is absorbed and transferred to the HTF in the form of heat. The geometrical and optical parameters of the LS2 collector have been considered for study as presented in Table 141.

This study examines three distinct absorber designs, labeled AT1, AT2, and AT3, as illustrated in Fig. 2, a and b, and c, respectively46,47. AT1 represents a basic absorber without fins. AT2 features a single longitudinal triangular fin positioned at the absorber’s inner bottom section. AT3, another finned design, incorporates two longitudinal rectangular fins situated at the absorber’s areas of highest flux concentration39.

SolTrace simulation

The study of heat transfer within the absorber tube necessitates an understanding of the concentrated variable heat flux incident on its surface. This has been calculated using the SolTrace 2016.12.22 software48. SolTrace uses the MCRT method to carry out the numerical ray racing. For the PTC system, simulations were conducted using the parameters outlined in Table 1. A Gaussian distribution with a 2.6 mrad cone angle was used to model the sun32. In all ray-tracing simulations, the tracking system of the PTC was assumed to be flawless, with a direct normal irradiation (DNI) of 1000 W/m2.Both the mirror’s specularity and slope errors were configured at 3 mrad32,49. The SolTrace 2016.12.22 software is validated by comparing the peripheral local heat flux obtained from the numerical ray tracing with peripheral heat flux obtained from the analytical technique of Jeter33. The numerical ray tracing results are well agreed with analytical results as presented in the authors’ recent article, Donga, R. K. et al.46,47.

Thermal analysis

Heat flux distributions derived from ray-tracing simulations were utilized in the thermal analysis of the receiver. The numerical simulations of the receiver provided data on the useful heat gain by the heat transfer fluid (HTF) and the pressure drop during fluid flow. These results were crucial in determining both thermal and overall efficiency. Furthermore, the simulations revealed temperature gradients within the absorber. The numerical simulations of the parabolic trough collector (PTC) receiver assembly were conducted using the finite volume method (FVM) implemented in Fluent 2019R3 software, which employs the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equation50.The time-averaged formulations for turbulent flow, expressed through these equations, encompass the principles of mass, momentum, and energy conservation46,47,51. The specific mathematical expressions for these principles are detailed in Eqs. (1)–(3)32. In all simulations, the Realizable k-ε turbulence model with enhanced wall treatment was utilized32. This model was chosen for its superior capability in predicting turbulent flows. The enhanced wall treatment improves near-wall resolution, thereby ensuring precise heat transfer predictions, which is crucial for assessing the thermal performance of the absorber tube. For modeling radiative heat transfer, the discrete ordinates (DO) radiation model was employed. This approach was used alongside the equations governing mass, momentum, and energy conservation. To enhance the convergence speed of the numerical simulations while maintaining high stability, the pressure and velocity were integrated using the coupled algorithm. The energy and momentum equations were discretized using the second-order upwind scheme, whereas the pressure discretization was conducted with the PRESTO scheme. For turbulent kinetic energy, turbulent dissipation, and discrete ordinates, the first-order upwind scheme was applied. The convergence criteria for scaled residuals were set to be less than 10 < sup>-6</sup > for all simulations conducted.

Continuity equation:

Momentum equation:

Energy equation:

Assumptions in the simulations

The thermal analysis considers the following assumptions: (I) the flow is steady, (II) all surfaces are diffusive and gray, (III) homogeneous and isotropic material properties, (IV) incompressible fluid, (V) the turbulent kinetic energy generated by buoyancy effects is neglected, (VII) the vacuum level between the glass cover and absorber is very high, meaning that the conduction and convection are neglected and only radiation is considered in the evacuated space, and (VIII) HTF is syltherm800 and temperature-dependent fluid properties are considered. The viscosity (µ), specific heat (cp.), density (ρ), and thermal conductivity (λ) are given in Appendix36.

Boundary conditions

The following boundary conditions have been considered in this study:

Inlet: The mass flow rate (0.5 to 5.5 kg/s) and temperature (300 to 650 K) are specified for the HTF.

Outlet: A pressure outlet boundary condition is applied at the outlet.

Absorber’s interior surface: A no-slip boundary condition has been implemented.

Absorber’s exterior surface: A non-uniform peripheral solar flux, derived from SolTrace 2016.12.22, was applied to the outer surface of the absorber tube.

The emissivity of the coated material Luz Cermat on the absorber was calculated using Eq. (4) as proposed by Forristall (Forristall 2003).

Outer surface of the glass tube: Radiation and convection boundary conditions have been applied to the outer surface of the glass cover. The Stefan–Boltzmann law has been employed to determine the radiative heat transfer occurring between the sky and the outer surface of the glass cover. The sky was represented as a vast dome, and its effective temperature was calculated using Eq. (5)32,37.

The ambient temperature and heat transfer coefficient derived from Eq. (6), as presented by Mullick and Nanda52were employed in the calculation of heat loss from the glass cover’s exterior surface through convective heat transfer.

For all simulations in this research, the surrounding temperature was maintained at 298 K, while the air velocity was fixed at 2 m/s.

To conduct the FVM analysis, a structured mesh has been created for the geometry, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Near the wall, a finer mesh was constructed to capture the strong temperature and velocity gradients. The scaled residual limit was set to 10−6 as the convergence criterion for all governing equations.

Mesh independent test and validation

A mesh independence analysis was conducted to determine the optimal mesh size, as outlined by46,47. The analysis identified that the optimal number of cells for AT1, AT2, and AT3 were 857,472, 1,003,574, and 2,386,271, respectively. The simulation results were validated against experimental findings by Dudley and Kolb41. The computational and experimental results exhibit excellent correlation, as demonstrated in Table 2.

The following parameters have been evaluated from the thermal analysis. Equation (7) was utilized to compute the average Nusselt number. In this equation, \(\bar {h}\) denotes the average heat transfer coefficient, which is determined using Eq. (8). The thermal energy absorbed by the HTF, represented by Qa, is calculated using Eq. (9), where \(\:\bar{{T}_{i}}\) represents the average HTF temperature at the inlet and \(\:\bar{{T}_{o}}\) represents the average HTF temperature at the outlet. The average inlet and outlet temperatures are determined using the mass-weighted average function in the Fluent2019R3 software.

The friction factor (f) is calculated using Eq. (10). In this formula, the pressure loss per unit length is denoted by ΔPl.

To assess the improvement in PTC heat transfer efficiency, performance evaluation criteria (PEC) can be employed for the PTC receiver at a specified pumping power17,53.

The formula for calculating the PEC is outlined in Eq. (11). In this equation, fuf and Nuuf represent the average friction factor and average Nusselt number for the absorber without fins, respectively. Similarly, ff and Nuf indicate the average friction factor and average Nusselt number for the absorber with fins, respectively. When the PEC values exceed one, it signifies that the overall heat transfer performance of the PTC receiver is enhanced by the addition of fins to the absorber, given a constant pumping power.

Equation (12) was utilized to compute the PTC’s thermal efficiency28.

Results and discussion

The PTC simulation outcomes for the three absorbers are displayed and compared. In the current analysis, 3 mrad of slope error was assumed, which was experimentally determined in study. Table 1 presents the parameters of the PTC examined in this investigation. Figure 4 depicts the circumferential heat flux on the absorber. The absorber’s lower section experiences higher heat flux due to focused solar radiation, while the upper portion experiences less intense heat flux directly from the sun. The variable heat flux generates substantial temperature gradients within the absorber. These increased temperature gradients induce thermal strains, and thus distort the absorber.

Figure 5 compares the temperature gradients in the three absorbers for the HTF volumetric flow rate of 31.05 m3/h and entry temperature of 600 K. The flow rate of 31.05 m3/h examined in this study approximates the value of 30.8 m3/h utilized in the investigations of Mwesigye, Huan32 and the value of 31.8 m3/h employed in the study of Forristall54. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the absorbers’ temperature gradients resemble the heat flux profile pattern. In all three scenarios, the bottom portion of the absorber demonstrates higher temperatures than the top portion. This thermal gradient is caused by the non-uniform distribution of heat flux across the absorber’s surface. Figure 5a–c illustrates that the temperature gradients in AT1, AT2, and AT3 are nearly identical. The integration of fins, as depicted in Fig. 5b, c, leads to improved heat transfer and a more uniform temperature distribution compared to the smooth tube shown in Fig. 5a. The configuration with two fins (Fig. 5c) exhibits superior performance relative to the one-fin configuration (Fig. 5b), as indicated by the more uniform temperature distribution across the absorber tube. In all instances, the absorbers exhibit a maximum temperature differential of 28 K between their highest and lowest points, which is within the acceptable range for the reliable operation of the PTC receiver50. The AT3 design incorporates longitudinal fins located at the absorber’s peak heat flux area, thereby enhancing the rate of heat transfer46,47.

Figure 6 demonstrates the relationship between the Re and both the average Nu and average friction factor at a 600 K inlet temperature. The graph demonstrates that for all three absorbers, the average Nusselt numbers are lower when Reynolds numbers are smaller. Additionally, the Nusselt number shows an upward trend as the Re increases. The finned absorbers (AT2 and AT3) demonstrate higher average Nusselt number values compared to the un-finned absorber, revealing improved heat transfer efficiency. Among the finned absorbers, AT3, which features two longitudinal fins, exhibits greater average Nusselt number values than AT2. This suggests that the absorber AT3 transfers a larger amount of heat to the fluid, attributed to the presence of two longitudinal fins positioned at the absorber’s maximum flux points. Compared to AT1, the Nusselt number shows a maximum enhancement of 18.3% for AT2 and 40.1% for AT3. At a Reynolds number of 2.82 × 105, the maximum value of the Nusselt number is attained for all three absorbers. As shown in Fig. 6, the average friction factors are highest for the three absorbers with the lowest Reynolds numbers, and they decrease as the Re increases. The research conducted by Cheng, He17,36,39 demonstrates a comparable trend in friction factor. The finned absorbers (AT2 and AT3) exhibit marginally increased friction factor values compared to the un-finned absorber (AT1), which can be attributed to the greater pressure loss experienced in the finned configurations. There is no noticeable variation between the absorber with two fins and the absorber with one fin in terms of the average friction factor.

Figure 7a illustrates the relationship between PEC and Re for the three absorbers. The results indicate that the PEC values for AT2 and AT3 exceed one, while the un-finned absorber demonstrates a PEC value of one. This suggests an improvement in the overall heat transfer efficiency for both types of finned absorbers. Compared to AT2, AT3 exhibits greater PEC values. For an absorber equipped with two fins, the PEC shows no notable changes across different Reynolds numbers. For AT2, the PEC reaches its peak value of 1.19 when the Reynolds number is 0.25 × 105. In contrast, AT3 exhibits a maximum PEC of 1.28 at a Reynolds number of 2.83 × 105. The results suggest that placing two longitudinal fins at the absorber’s maximum flux point is more effective than using a single longitudinal fin. Given that the density of the Heat Transfer Fluid (HTF) is temperature-dependent, temperature variations within the absorber region lead to the formation of density gradients. These gradients generate buoyancy-driven forces, which subsequently induce the movement of the HTF in the y-direction (typically vertical or transverse to the primary flow). This movement enhances fluid mixing and promotes more effective convective heat transfer. Consequently, the finned absorber tubes exhibit improved thermal performance, as the increased flow in the y-direction facilitates enhanced heat absorption and distribution along the tube surfaces. Figure 7b demonstrates the influence of HTF inlet temperature on thermal efficiency.

The results demonstrate that thermal efficiency exhibits an inverse relationship with inlet temperature, reaching its maximum at lower inlet temperatures and decreasing as inlet temperature increases. This phenomenon occurs due to the reduced heat loss from the absorber at lower inlet temperatures and the inverse relationship at higher temperatures. Figure 7b demonstrates that the PTC equipped with finned absorbers (AT2 and AT3) achieves greater thermal efficiency compared to the configuration using an un-finned absorber (AT1). The thermal efficiency exhibits a higher value for the absorber AT3 in comparison to AT2. The study shows that enhanced heat transfer is attained in the AT3 absorber through the incorporation of two lengthwise fins positioned at the areas of peak flux on the absorber. AT2 and AT3 may boost the PTC’s thermal efficiency by 0.9% and 1.45%, respectively, as compared to AT1.

Conclusions

The study investigates the enhancement of heat transfer in parabolic trough collectors (PTCs) by incorporating longitudinal fins within the tubular absorber. Numerical simulations were performed on different absorber designs to improve heat transfer in the PTC receiver. The setup includes a receiver without any fins, one with a single fin, and another with two fins. The performance improvement of the LS2 collector has been investigated. A comprehensive investigation of heat transfer, encompassing radiation, is conducted. Given the variable heat flux on the absorber. Using the MCRT and FVM techniques, simulations were conducted for Reynolds numbers ranging from 0.25 × 105 to 2.82 × 105.

For the three absorbers, the variation in friction factor and Nusselt number with Re is shown. PEC variation with Re is also shown. The PEC serves as an indicator of overall enhancement in heat transfer efficiency. It incorporates both the Nusselt number and friction factor to provide a comprehensive assessment of heat transport improvement. The incorporation of finned absorbers significantly enhances the overall heat transfer efficiency of the PTC. In comparison to the conventional smooth absorber, the Nusselt number exhibits a maximum enhancement of 18.3% for the absorber equipped with one fin and 40.1% for the absorber equipped with two fins. At a Reynolds number of 2.82 × 105, the maximum value of the Nusselt number is attained for all three absorbers. The absorber with two fins demonstrates a higher PEC value compared to the one with a single fin. The absorber equipped with two fins and the absorber equipped with one fin demonstrate maximum PEC values of 1.28 and 1.19, respectively.

The friction factor, a critical parameter for quantifying flow resistance, was evaluated, revealing that finned absorbers marginally increased pressure losses in comparison to the finless configuration. Nevertheless, this increase was counterbalanced by the corresponding enhancement in heat transfer efficiency, as demonstrated by the PEC values.

This investigation examines two distinct fin configurations in the tubular absorber of a parabolic trough collector (PTC) receiver. The investigation reveals that the placement of fins at the two points of maximum solar flux substantially enhances heat transfer in comparison to the utilization of a single fin at the base of the absorber. This configuration enhances the absorber’s capacity to distribute thermal energy more efficiently, resulting in improved system performance. Nevertheless, the research underscores the necessity for additional investigation to ascertain the optimal dimensions of these longitudinal fins. Critical parameters such as fin length, thickness, and height necessitate thorough investigation to optimize heat transfer while minimizing material costs and pressure losses.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are provided within the manuscript. Any additional data required will be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Absorber inner surface area (m2)

- a:

-

Focal length (m)

- \({c}_{p}\) :

-

HTF specific heat (J/kg K)

- \({d}_{gti}\) :

-

Glass cover inner diameter (mm)

- \({d}_{gto}\) :

-

Glass cover outer diameter (mm)

- \({d}_{rti}\) :

-

Absorber inner diameter (mm)

- \({d}_{rto}\) :

-

Absorber outer diameter (mm)

- \({d}_{h}\) :

-

Hydraulic diameter (m)

- f :

-

Average friction factor

- \({f}_{f}\) :

-

Average friction factor for finned absorber

- \({f}_{uf}\) :

-

Average friction factor for un-finned absorber

- h:

-

Heat transfer coefficient at the outer surface of glass cover (W/m2 K)

- \(\overline{h }\) :

-

Average heat transfer coefficient at the inner surface of absorber (W/m2 K)

- L:

-

Receiver length (m)

- \(\dot{m}\) :

-

Mass flow rate of HTF (kg/s)

- Nu:

-

Average Nusselt number

- \({\text{Nu}}_{\text{f}}\) :

-

Average Nusselt number for finned absorber

- \({\text{Nu}}_{\text{uf}}\) :

-

Average Nusselt number for un-finned absorber

- \(\Delta {\text{P}}_{l}\) :

-

Pressure drop per unit length (Pa/m1)

- \({\text{Q}}_{a}\) :

-

Heat absorbed by HTF (W)

- \(Q\) :

-

Local heat flux on absorber (W/m2)

- Re:

-

Reynolds number

- \({\text{T}}_{\text{a}}\) :

-

Ambient air temperature (K)

- \({\text{T}}_{\text{htf}}\) :

-

Average HTF temperature (K)

- \({\text{T}}_{rto}\) :

-

Surface temperature of absorber (K)

- \({\text{T}}_{i}\) :

-

HTF inlet temperature (K)

- \({\text{T}}_{o}\) :

-

HTF outlet temperature (K)

- \({\text{T}}_{s}\) :

-

External radiation temperature (K)

- \({\text{T}}_{wall}\) :

-

Average absorber inner wall temperature (K)

- \(\overline{\text{T} }\) :

-

Average temperature of heat transfer fluid at a cross-section (K)

- \({V}_{w}\) :

-

Wind velocity

- W:

-

Aperture width (m)

- \(\alpha {\text{}}_{\text{r}}\) :

-

Absorber absorptivity

- \({\upvarepsilon }_{\text{ro}}\) :

-

Absorber coating emissivity

- \({\upeta }_{\text{th}}\) :

-

Thermal efficiency

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of HTF (W/m K)

- \(\mu\) :

-

Viscosity of HTF (Pa/s)

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density of the HTF (kg/m3)

- \({\rho }_{m}\) :

-

Mirror reflectivity

- \({\rho }_{\text{g}}\) :

-

Glass cover reflectivity

- \({\rho }_{r}\) :

-

Absorber reflectivity

- \({\tau }_{\text{g}}\) :

-

Glass cover transmissivity

- \({\tau }_{m}\) :

-

Mirror transmissivity

References

Caballero, G. C. et al. Thermal analysis of a parabolic trough collectors system coupled to an organic Rankine cycle and a two-tank thermal storage system: case study of Itajubá-MG Brazil. Energies 15, 8261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15218261 (2022).

Rodat, S. & Thonig, R. Status of concentrated solar power plants. Clean. Technol. 6, 365–378. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol6010018 (2024).

Forman, P. et al. A survey of solar concrete shell collectors for parabolic troughs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 134, 110331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110331 (2020).

Ajbar, W., Parrales, A., Huicochea, A. & Hernández, J. A. Different ways to improve parabolic trough solar collectors’ performance over the last four decades and their applications: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 156, 111947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111947 (2021).

Reddy, K. S., Kumar, K. R. & Satyanarayana, G. V. Energy-efficient receiver for solar concentrator. Heat. Transf. Eng. 29, 961–972 (2008).

Ray, S. et al. Performance analysis of receiver: coating, vacuum and glass cover. Int. J. Energy Res. 42, 4235–4249. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.4137 (2018).

Talem, N. et al. Thermal performance of parabolic trough collector with nanofluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 256, 124128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.124128 (2024).

Panduro, E. A. C. et al. A review of the use of nanofluids in parabolic-trough collectors. Appl. Therm. Eng. 211, 118346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.118346 (2022).

Reddy, K. S. & Satyanarayana, G. V. Porous finned receiver study for solar concentrator. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2, 172–184 (2008).

Akbarzadeh, S. & Valipour, M. S. Heat transfer enhancement in parabolic trough collectors: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 92, 198–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.093 (2018).

Muñoz, J. & Abánades, A. A technical note on application of internally finned tubes in solar parabolic trough absorber pipes. Sol Energy. 85, 609–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2011.01.002 (2011).

Cheng, Z. D., He, Y. L. & Cui, F. Q. Numerical study of heat transfer enhancement by unilateral longitudinal vortex generators inside parabolic trough solar receivers. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 55, 5631–5641 (2012).

Amina, B., Miloud, A., Samir, L., Abdelylah, B. & Solano, J. P. Heat transfer enhancement in a parabolic trough solar receiver using longitudinal fins and nanofluids. J. Therm. Sci. 25, 410–417 (2016).

Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C. & Tsimpoukis, D. Thermal enhancement of parabolic trough collector with internally finned absorbers. Sol Energy. 157, 514–531 (2017).

Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C., Daniil, I. & Antonopoulos, K. A. The impact of internal longitudinal fins in parabolic trough collectors operating with gases. Energy Convers. Manag. 135, 35–54 (2017).

Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C. & Tsimpoukis, D. Multi-criteria evaluation of parabolic trough collector with internally finned absorbers. Appl. Energy. 205, 540–561 (2017).

Gong, X. et al. Heat transfer enhancement analysis of tube receiver for parabolic trough solar collector with pin fin arrays inserting. Sol Energy. 144, 185–202 (2017).

Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C. & Tsimpoukis, D. Optimum number of internal fins in parabolic trough collectors. Appl. Therm. Eng. 137, 669–677 (2018).

Abu-Hamdeh, N. H., Bantan, R. A., Khoshvaght-Aliabadi, M. & Alimoradi, A. Effects of ribs on thermal performance of curved absorber tube used in cylindrical solar collectors. Renew. Energy. 161, 1260–1275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.07.077 (2020).

Farnam, M. & Khoshvaght-Aliabadi, M. Analysis of twisted structure absorber tube and effects of specific design factor in solar collectors. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 52, 102113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.102113 (2022).

Allam, M., Tawfik, M., Bekheit, M. & El-Negiry, E. Experimental investigation on performance enhancement of parabolic trough concentrator with helical rotating shaft insert. Sustainability 14, 14667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214667 (2022).

Venkatesaperumal, R. et al. Heat transfer in parabolic trough collector using corrugated tube. Sustainability 15, 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010378 (2022).

Roohi, R. et al. Absorber tube of a parabolic trough collector with helical inserts. Sustainability 15, 10637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310637 (2023).

Said, S. et al. New evacuated tube solar collector for domestic water heating. Sustainability 15, 11497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511497 (2023).

Limboonruang, T. et al. Optimizing solar parabolic trough receivers with external fins. Energies 16, 6520. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16186520 (2023).

Golzar, A. et al. Numerical simulation of a parabolic through solar collector with a novel geometric design. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09374-y (2024).

Donga, R. K., Kumar, S. & Velidi, G. Numerical investigation of performance and exergy analysis in parabolic trough solar collectors. Sci. Rep. 14, 31908. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83219-4 (2024).

Donga, R. K. & Karn, A. Improving the thermal performance of parabolic trough solar collectors by incorporating cylindrical attachments within the absorber tube. Appl. Therm. Eng. 126587 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.126587 (2025).

Liang, H., You, S. & Zhang, H. Comparison of different heat transfer models for parabolic trough solar collectors. Appl. Energy. 148, 105–114 (2015).

Padilla, R. V. et al. Heat transfer analysis of parabolic trough solar receiver. Appl. Energy. 88, 5097–5110 (2011).

Burkholder, F. & Kutscher, C. Heat-Loss Testing of Solel’s UVAC3 Parabolic Trough Receiver. NREL Tech. Rep. NREL/TP-550-42394 (2008).

Mwesigye, A. et al. Influence of optical errors on thermal and thermodynamic performance. Sol Energy. 135, 703–718 (2016).

Jeter, S. M. Calculation of the concentrated flux density distribution in parabolic trough collectors. Sol Energy. 37, 335–345 (1986).

Khanna, S. & Sharma, V. Analytical expression for solar flux distribution on undeflected absorber tube. J. Sol Energy Eng. 138, 011010 (2015).

Zhao, D. et al. Installation and tracking error effects in solar parabolic trough collector. Renew. Energy. 94, 197–212 (2016).

Cheng, Z. D. et al. Numerical simulation of a parabolic trough solar collector with nonuniform solar flux conditions by coupling FVM and MCRT method. Sol Energy. 86, 1770–1784 (2012).

Ghomrassi, A., Mhiri, H. & Bournot, P. Numerical study and optimization of parabolic trough solar collector receiver tube. J. Sol Energy Eng. 137, 051003 (2015).

Cheng, Z. D. et al. Three-dimensional numerical study of heat transfer characteristics in the receiver tube of parabolic trough solar collector. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Transf. 37, 782–787 (2010).

He, Y. L. et al. A MCRT and FVM coupled simulation method for energy conversion process in parabolic trough solar collector. Renew. Energy. 36, 976–985 (2011).

Donga, R. K. & Kumar, S. Parabolic trough collector with rhombus tube absorber for higher concentration ratio. Energy Sources A. 40, 2620–2631 (2018).

Dudley, E. V. et al. Test Results: SEGS LS-2 Solar Collector. SAND94-1884 (1994).

Roesle, M., Coskun, V. & Steinfeld, A. Numerical analysis of heat loss from a parabolic trough absorber tube with active vacuum system. J. Sol Energy Eng. 133 https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4004276 (2011).

Mwesigye, A., Bello-Ochende, T. & Meyer, J. P. Numerical investigation of entropy generation in a parabolic trough receiver. Energy 53, 114–127 (2013).

Wu, Z. et al. 3D numerical study of heat transfer in parabolic trough receiver. Appl. Energy. 113, 902–911 (2014).

Li, Z. Y., Huang, Z. & Tao, W. Q. Three-dimensional numerical study on fully-developed mixed laminar convection in parabolic trough solar receiver tube. Energy 113, 1288–1303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.07.148 (2016).

Donga, R. K. & Kumar, S. Three-Dimensional Optical and Thermal Analysis of Parabolic Trough Solar Collector: A Numerical Study. Ph.D. Thesis, UPES, India (2019).

Donga, R. K. & Kumar, S. Thermal performance of parabolic trough collector with absorber tube misalignment and slope error. Sol Energy. 184, 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.04.007 (2019).

Wendelin, T. & SolTRACE optical modeling tool for concentrating solar optics. In ASME Conf. Proc. 2003, 253–260 (2003).

Wendelin, T. & Parabolic Trough, V. S. H. O. T. Optical Characterization 2005–2006. US DOE/NREL (2006).

Wang, P., Liu, D. Y. & Xu, C. Heat transfer enhancement using metal foams in parabolic receiver. Appl. Energy. 102, 449–460 (2013).

Emani, S. et al. Effects of wavy structure, ambient conditions and solar intensities on flow and temperature distributions in a mini solar flat plate collector using computational fluid dynamics. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/19942060.2023.223619

Mullick, S. C. & Nanda, S. K. An improved technique for computing the heat loss factor of a tubular absorber. Sol Energy. 42, 1–7 (1989).

Wang, S., Guo, Z. Y. & Li, Z. X. Metallic filament insert for heat transfer enhancement. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 44, 1373–1378 (2001).

Forristall, R. Heat Transfer Analysis and Modeling of a Parabolic Trough Solar Receiver. NREL Tech. Rep. (2003).

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was self-funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K.D.: methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, project administration. S. K.: conceptualization, review and editing. G.V.: conceptualization, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent to participate

All authors confirmed that informed consent was obtained, and that no human subjects or human factors were involved in this study.

Consent to publish

All authors have given their consent for publication of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The properties of the heat transfer fluid syltherm800 are temperature dependent. The viscosity (µ), specific heat (cp.), density (ρ), and thermal conductivity (λ) are given in the Eqs. (13) to (16).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Donga, R.K., Kumar, S. & Velidi, G. Heat transfer enhancement in a parabolic trough collector using finned tubular absorber. Sci Rep 15, 24142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07825-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07825-6