Abstract

Soil salinity surge, and accumulation of heavy metals in soil, due to agricultural malpractices and natural calamities, is a growing concern worldwide. The use of bacteria for bioremediation, and the potential of halotolerant bacteria have not been fully explored. This study aimed to find indigenous halotolerant bacteria, from the agricultural soils of Indian Sundarbans that have multi-metal removal and fertility intensification abilities. Three halotolerant (≥ 20% NaCl) indigenous Bacillus strains (T37, T40, T41) isolated from our soil samples demonstrate exceptional heavy metal tolerance and removal abilities. T40 removed 79.62% Lead and 86.20% Chromium—which is more effective than previous reports. T41 removed 88.46% Nickel, twice that from earlier findings. Secretion of Exopolysaccharide, and FESEM-EDX mapping confirmed metal adhesion. Additionally, AES’s quantification of heavy metal in exopolysaccharide explains the biosorption mechanism. These bacteria could also solubilize phosphorus significantly under metal stress, offering sustainable soil remediation potential for wasteland reformation and agriculture. Accordingly, farmers may effectively use these bacterial strains as biofertilizers to reclaim the contaminated soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heavy metal (HM) contamination in soil poses a serious health risk globally, including in Central and Eastern Europe, the USA, China, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh1. HM contamination arises from various sources, including compost, fertilizers and pesticides, anthropogenic and industrial activities2,3, such as industrial effluents, mine tailings, municipal waste, and HM-enriched waste4. HMs are non-biodegradable, persist in the soil for extended periods, and potentially enter the food chain5. Their availability and mobility in soil are influenced by precipitation, mineralization, adsorption, and protonation6.

Soil microbes play a crucial role in HM removal through bioremediation and help to maintain soil health7. Over time, several HM-tolerant bacteria have been identified. Strains of Bacillus cereus can tolerate Nickel (Ni²⁺), Copper (Cu²⁺), Cobalt (Co), and Cadmium (Cd²⁺)8, whereas strains of Raoultella sp. and Klebsiella sp. can effectively remove various metal cations, such as Arsenic (As³⁺), Lead (Pb²⁺), Cu²⁺, Manganese (Mn²⁺), Zinc (Zn²⁺), Cd²⁺, Chromium (Cr⁶⁺), and Ni²⁺, both individually and in multi-metal solutions9. Bacterial strains are often studied for their bioremediation potential–minimal disruption of the natural soil environment, ability to enhance soil fertility, and cost-effective application10,11. Bacteria employ several mechanisms to remediate HMs from soil, including bioleaching, biosorption, and biotransformation into non-toxic compounds. Their adaptability to environmental changes and rapid rate of growth make them well-suited for remediation7,11,12.

Soil salinity is another significant agricultural challenge, affecting approximately 8.7% of the world’s agricultural land, totaling over 833 million hectares13,14. Bacteria capable of surviving in saline conditions are known as halophiles. In contrast, halotolerant bacteria could survive in 0 to ≥ 20% salt concentrations, which is particularly noteworthy15,16,17,18. Halotolerant bacteria have demonstrated beneficial properties, including the solubilization of inorganic phosphates, siderophore production, nitrogen fixation in soil19,20,21, and anti-pathogenic abilities22. They have also shown tolerance to HMs; for example, halophiles like Halomonas sp. and Halobacillus trueperi have exhibited tolerance to Lead, Copper, and Zinc, respectively8. Stenotrophomonas maltophila strain BN123. Similarly, Halomonas sp. Exo1, isolated from the halophilic areas of the Indian Sundarbans mangroves has metal resistance properties24.

Bioremediation using bacteria aims to maintain soil structure integrity, and aid in the degradation of both inorganic and organic hydrocarbons25. Previously, strains of Pseudomonas alcaligenes, Bacillus vietnamensis, and Kocuria flava isolated from the Indian mangroves have been seen to remediate Arsenic and hydrocarbons26. However, bacterial remediation’s drawbacks include a potentially extended time frame, specificity to specific environments, and the possibility of toxic byproducts27. While considerable research has focused on bacteria, including halotolerant strains, the range of explored bacterial strains remain limited, and the effect of salinity variations on their bioremediation capabilities requires further investigation9. Additionally, there is a need to identify single bacterial strains that are capable of simultaneously remediating multiple metals. This is crucial for developing effective bacterial-based bioremediation methods for soil28.

This study focuses on identifying and isolating halotolerant, free-living bacteria from the saline soils of Indian Sundarban agricultural soils. These bacteria must also exhibit multi-metal tolerance, and soil NPK restoration abilities. Hence we also investigate their ability to enhance Nitrogen-Phosphorus-Potassium (NPK) levels in the soil. The aim is to develop a bioremediation technique that not only removes HMs from soil but also restores fertility in degraded soils, potentially transforming wastelands into valuable cultivable lands sustainably. To summarize, the objectives of this study may be framed as.

-

To identify halotolerant bacterial strains from soil samples with multi-metal tolerance.

-

To study and confirm the removal of HMs by these strains {focusing on Lead (Pb), Chromium (Cr), and Nickel (Ni) based on initial screening responses, as these are hazardous and often found only in traces}.

-

To investigate these strains’ fertility enhancement properties (N₂ fixation, P- and K solubilization).

Results

Isolation of halotolerant bacteria

Fifty halotolerant bacteria were isolated from the agricultural soils of Sagar Island, an Indian mangrove region. These isolates showed growth in low NaCl concentrations (1.5% NaCl supplemented Nutrient Medium) and high NaCl concentrations (Nutrient Medium with 20% NaCl).

Screening of HM-tolerant bacteria

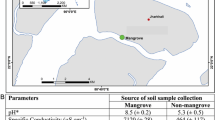

All 50 isolated strains were grown in HM concentrations. A Venn diagram generated through R-software (Fig. 1(1.1)) illustrates that most of the bacterial strains could not tolerate HMs; 37 of them showed a response to either of the HMs, and 24 isolates responded significantly to all three- Pb, Cr and Ni. Further, the map in Fig. 1(1.2) (generated through ArcGIS 10.8 software) shows Cr-tolerant bacterial strains being restricted to a few places, whereas there is an abundance of Ni-tolerant bacteria. Also, the locations having more Pb-tolerant halotolerant bacteria had fewer Cr-tolerant halotolerant bacteria. Among all of the strains, three bacterial strains were found that could show significant growth in Pb, Cr and Ni (minimum 50 ppm concentration). They were all characterized as gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria.

Spatial distribution of HM tolerant bacteria in sampling areas and their nature of tolerance towards each HM: 1.1: In the image the sampling locations are shown using ArcMap 10.8, featuring a part of the Indian Sundarbans focusing on the sampling area of Sagar Island. 1.2: The map shows the varying number of salt tolerant bacterial strains tolerating Pb, Cr and Ni separately. The three colors are for the Number of Lead tolerating Bacteria (No. of LTB), Number of Chromium tolerating Bacteria (No. of CTB) and Number of Nickel tolerating Bacteria (No. of NTB). The map has been created using ArcMap10.8. 1.3: The Venn diagram generated through R v4.1.3, the total number of isolates responding to the minimum concentrations of 50ppm of HM were 24, only Pb = 2, only Cr = 1, only Ni = 4, just Pb&Cr = 3, just Pb&Ni = 6, just Cr&Ni = 4, Pb&Cr&Ni = 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

Three isolated strains have been shown to be highly efficient in tolerating all three metals. They could tolerate high concentrations of Cr, with T40 being able to tolerate > 2500 ppm. These strains could also tolerate high concentrations of Pb but had a lower tolerance towards Ni (given in Table 1 and shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). Comparison between the HM-tolerance levels in Table 1 and their respective permissible limits in Supplementary Table 1 showed that the bacterial strains could effectively tolerate HM in higher concentrations.

Biochemical tests

All the bacterial strains tested positive for Catalase and Indole production. None of the isolates responded to Urease or Oxidase. Isolates T40 and T41 tested positive for Voges-Proskaeur, and T37 tested positive for Lactose fermentation and Citrate utilization.

Identification of the bacterial strains

In this study, out of 37 bacterial strains, several isolates showed tolerance towards one or two of the three HMs. However, only three displayed tolerance towards all three metals (Pb, Cr, and Ni) at higher concentration levels. These bacterial strains were identified based on 16S rRNA sequencing and BLAST, and the sequences were deposited in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database. The BLAST results along with accession numbers of the respective sequences are as follows: T37 was identified as Bacillus megaterium with 99.86% similarity (Accession number: OQ979046), T41 was identified as Bacillus aryabhattai (Accession number: OQ979125) with 99.89% similarity, and T40 was identified as Bacillus altitudinus (Accession number: OQ983889) with a similarity percentage of about 99.71%. Their similarity with other Bacillus species using a phylogenetic tree (with MEGA7 software) has been illustrated in Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic Tree Of The Bacterial Isolates: The Phylogenetic tree for strains with accession number of OQ979046, OQ979125 and OQ983889 were prepared with MEGA 7 taking Escherichia coli strain as the out-group. The identified strains are marked in red. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-3686.92) is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths (0.299) measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 11 nucleotide sequences. There were a total of 1749 positions in the final dataset. The Test of Phylogeny was using Bootstrap method with 1000 Bootstrap Replications.

Bacterial potential of HM removal

The potential for reducing HM was measured using the difference between the initial and final HM concentration in the solution. The percentage removal was calculated using the formula mentioned in “Sample preparation and atomic emission spectroscopy (AES) analysis”. The samples prepared were analyzed using MP-AES, and it was found that the three strains were able to remove Pb, Cr and Ni as given in Table 1 and shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Scanning electron microscopy- energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) analysis of bacterial metal adsorption

All the bacterial strains exhibited effective removal of HMs, and their removal process was studied using SEM-EDX. In Fig. 3, a comparison in appearances of the bacterial cell walls among the bacterial isolates before being treated by HMs {images (1), (5) and (9)} and post application (with magnification), is shown. Additionally, the metals attached to and sequestered within the bacterial cell walls was confirmed through EDX mapping of the T40 strain as given in Fig. 3(13,15 &17). The peaks of the relevant HMs in Fig. 3 (14, 16 &18) confirm this. Images given in Fig. 4 provide a broader view of HM absorbance by individual bacteria in a mixture of HMs, within the bacterial network, proving their ability to remove HM in the broth, as shown in Table 1. In 4.1, 4.2, and 4.3, the absorbance of HMs by the bacteria is visualized when treated together, and the peaks of the respective strains in 4.4, 4.5, and 4.6 support this. Additionally, images 4.7, 4.8 and 4.9 for T37; 4.10, 4.11 and 4.12 for T41; and 4.13, 4.14 and 4.15 for T40 show the presence of HM ions separately and in varying concentrations within the network, color coded for clarity as mentioned in the caption for Fig. 4.

Images showing differences in bacterial cells in HMs and in control; EDX mapping to confirm the presence of respective HMs on cell surface: (Top): The images on of the bacterial isolates are taken through SEM [Hitachi, Japan; Model: SU8010 series] (1–12). Images (1), (5) and (9) with 30000X magnification, are control images of T37, T40 and T41 bacterial strains respectively; (2), (3) and (4) are images of T37 in presence of Pb, Cr and Ni respectively with magnified images of the same at the bottom [magnification 35000X]; (6), (7) and (8) are images of T40 in presence of Pb, Cr and Ni respectively with magnified images of the same at the bottom [magnification 35000X]; (10, (11) and (12) are images of T41 in presence of Pb, Cr and Ni respectively with magnified images of the same at the bottom [magnification 35000X]. (Bottom): The images of the bacterial isolate T40 are generated using FESEM-EDX [Hitachi, Japan; Model: SU8010 series]. The images (13), (15) and (17) shows the heavy metal ions- Pb, Cr and Ni respectively, attached and embedded along cell wall and EPS network of the bacterial cells. Alongside the images, the graphs generated through EDX-mapping as shown in (14), (16) and (18) also proved the presence of these HM on the bacterial cells.

SEM-EDX showing the presence of HMs on bacterial cell walls and network in HM mixture: the above images are generated through FESEM [Hitachi, Japan; Model: SU8010 series]-EDX and EDX mapping. Images (1), (2) and (3) shows the elements Pb (in yellow), Cr (in red) and Ni (in green) altogether at the same time attached to the bacterial cell wall and cell network for strains T37, T41 and T40 respectively. Images (4), (5) and (6) confirmed the presence of these elements on the bacterial cells through generation of peaks of the mentioned elements for T37, T41 and T40 respectively. Images (7, 8 & 9) for T37; (10, 11 & 12) for T41; and (13, 14 & 15) for T40, shows the elements individually (without the bacterial cells) as found in SEM images of bacterial cells. Here, Chromium = Red, Lead = Yellow and Green = Nickel.

Exopolysaccharide (EPS) formation by bacterial strains under HM stress

When the bacterial strains were grown under HM concentrations, they developed biofilms visible in borosilicate tubes. These biofilms, as seen in Figs. 5.4 and 5.5 appeared as purple rings in the tubes, confirming the presence of EPS and its involvement in the removal or absorption of HMs. It is evident that the HMs were located on the bacterial cell walls, attached to them, or within the EPS.

EPS extraction and EPS bound-HM measurement

Figures 4 and 5 provide an insight into the bacteria’s secretion of EPS when grown in the presence of all three HMs, demonstrating their ability to trap them. Extraction and measurement of the EPS secreted by the bacterial strains in the MIC concentration of the HMs, as given in Table 2, confirms it. Additionally, the concentrations of HMs found in the EPS, as analyzed by MP-AES, are also stated in Table 2, referring to the involvement in HM removal.

Fertilization abilities of the bacterial strains

All three bacterial strains tested positive for their fertilizing capabilities. They were able to fix nitrogen by growing in a nitrogen-free medium, solubilize insoluble forms of phosphate and potassium (grow in Pikovskaya agar and Aleksandrow agar), as shown in Fig. 5.

Phosphate solubilization efficiency under HM stress

Quantitative estimation of phosphorus solubilized by the bacterial strains in control and the presence of HMs is given in Supplementary Table 3. The notable difference in the capacity to solubilize phosphorus in control and in different HM-induced media can be seen clearly in Fig. 5 (bottom). It was found that in the presence of HM, the solubilizing potential of the bacterial strains significantly lowered, with T40 in Pb being the only exception. This unusual behavior has been further explained in “Discussions”.

(Top left) fertilizing properties, (top right) biofilm formation of the isolates and (bottom) difference in phosphate solubilization among bacterial isolates under HM stress: image (1, 2 and 3) of bacterial cultures, their capabilities for fertilizing properties are shown. The zone of potassium (2) and phosphate (3) solubilization are marked. All of the above images are of T40, with (1) in Jensen’s media, (2) in modified Aleksandrow media and (3) in Pikovskaya media. 4 & 5 shows formation of purple rings, circled in red, confirming biofilm formation by the isolates. Bottom graph shows the phosphate solubilization capabilities of the three Bacterial Strains with strain T40 exhibiting similar capability to solubilize phosphorus as much as in presence of Cr and Pb as in control conditions. The values are given in mean of triplicate values ± SD. The test was done using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test to find the level of significance. “*” means significant difference between phosphate present in negative control of Cr with Cr added broth treated with bacterial strains. The “**” means significant difference between phosphate present in negative control of Pb with Pb added broth treated with bacterial strains. The “***” means significant difference between phosphate present in negative control of Ni with Ni added broth treated with bacterial strains. (Significance means p < 0.05).

Discussions

Halotolerant bacteria have a unique physiology that allows them to grow in high concentrations of HMs, essential for bioremediation45. Earlier studies have shown HM tolerance among salt tolerant bacteria. It is exhibited due to its shared mechanism of ion removal, secretion of EPS in toxic environments and stress-responsive genes46,47. Some strains of Klebsiella sp. and Pseudomonas putida could survive in 15% of salinity as well as effectively tolerate and remove Mercury, Cadmium, Copper and Nickel48. The current work discusses three halotolerant Bacillus strains exhibiting tolerance towards Pb, Cr and Ni (Table 1). Their individual tolerance levels were higher than the respective permissible limits (Supplementary Table 1) with some MICs higher than previously reported. The multi-tolerance behavior of bacteria towards Pb, Cr and Ni were earlier found in: Bacillus safensis (Pb: 250ppm, Cr: 210ppm, and Ni: 110ppm), Enterobacter tabaci (Pb: 130ppm, Cr: 160ppm, and Ni: 90ppm), Planococcus maritimus (Cr: 500ppm), and Brevebacterium casei (Cr: 250ppm)49. T40 exhibited high tolerance towards Cr with an MIC of 2536 ± 5.29 ppm. In the past, Cr hyper tolerance has been seen in Bacillus sp. MH778713 tolerating up to 15,000 ppm as shown in Ramirez et al. 201950.

The abilities of the bacterial strains to remove HMs were found in the order—Cr: T40 > T37 > T41, highest by T40 with 86.20 ± 0.69%; Pb: T40 > T41 > T37, highest by T40 with 79.62 ± 1.84% and Ni: T41 > T37 > T40, highest by T41 with 88.46 ± 0.90% (given in Table 1). This when compared to previous findings like- a strain of P. aeruginosa removing approximately 29%, 30%, 35%, and 28% of Pb, Cr, Ni, and Cd, respectively51 and Lactobacillus plantarum MF042018 being able to efficiently remove Ni2+ and Cr2+ from broth medium by 33.8 ± 0.8% and 30.2 ± 0.5%52 was found to be significantly higher. Other studies showing higher removal percentage of Cr (approx 92%) by Bacillus licheniformis53, contradict the removal ability of Cr by T40. But, in this study, the novelty of the strains lies in multi-metal removal along with individual effects. Therefore, when grown in a mixture containing three HMs, their removal potential decreased, compared to individual HM removal31. Despite this, T40 shows the highest removal of Cr in mixture of 44.46 ± 6.09%, T41 could remove Pb by 47.60 ± 2.12% and T37 efficiently could remove 58.74 ± 3.62% of Ni. These prove the strains’ efficacy over other strains previously reported and discussed.

Earlier investigations have shown EPS production by bacteria playing a key role in HM removal, like— Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing EPS under HM stress54, Bacillus sp. GH-s29 reducing Arsenic, Chromium, and Cadmium by producing EPS30, Sporosarcina pasteurii generating EPS under Nickel stress55, Parapedobacter sp. ISTM3 strain identified in biosorption of Cr ions through EPS56 and so on. The present work also demonstrates removal of HM in broth by the combined effect of biosorption of HM and EPS (Table 2). The removal of HM through EPS formation, as observed under the microscope is given in Fig. 3 (1, 2 and 3). This mechanism can be attributed to the presence of uronic acids in EPS along with negatively charged functional groups like carboxyl, phosphoryl, and hydroxyl groups. These negatively charged groups present in EPS interact with the positively charged metal ions, resulting in biosorption process57. These findings are supported by FESEM-EDX mapping images and MP-AES, which have deciphered the considerable presence of HM in EPS. FESEM produces high-resolution images of these EPS structures. The more rugged bacterial surface shows enhanced metal adsorption capacity58. EDX-Mapping complements FESEM by providing elemental analysis which in turn confirms the presence of the metals on EPS surfaces The results can be found similar to Ni removal through EPS by Klebsiella oxytoca J7 from contaminated water59and, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Azotobacter chroococcum efficiently remediating lead, copper and lead, mercury respectively54,58. These findings consolidate the potential of the bacterial strains as bioremediating agents in saline multi-metal contaminated lands.

Further, particular Bacillus species60,61,62, Mesorhizobium63 and different bacterial consortia64 were seen to improve soil nutrient availability and plant growth, respectively. Similarly, these strains also exhibited NPK abilities, serving their purpose in soil fertility enhancement as well. Some bacterial strains also show a synergistic effect in HM remediation and enhancement of nutrient availability in plants65,66. Bacillus subtilis have been seen to solubilize phosphorus and improve wheat growth under Cr stress67. Here, the bacterial strains could also solubilize phosphorus under HM stress as shown in Fig. 4. Although the presence of HM decreased their level of solubilization, Strain T40 showed more phosphorus solubilization in presence of Pb than in absence of it. This, on further investigation was found to be due to the difference in pH during the experiment. Phosphate solubilization alters the pH of the media due to the release of organic acids involved in the process of solubilization and addition of HMs might alter this pH. Although Potassium chromate and Nickel chloride do not react with phosphate, lead shares a different dynamic. Pb forms precipitate with the soluble phosphate, facilitating in an increased release of soluble phosphorus from insoluble sources68. Here, it was observed, that at the end of the experiment the pH of Pb incorporated media had reduced to 4.42 while the positive control had pH of 4.67. This was comparatively lower than the ones enhanced with Cr and Ni (4.7 and 4.58 respectively). The increased production of phosphorus causes the release of higher organic acids and hence the drop in pH69. The complexity of the reactions and different pH levels caused the unusual result that was seen in Fig. 5. (bottom). Therefore, these isolates can also be tested for soil reformation in contaminated areas in the future.

Conclusion

In this current study, three halotolerant Bacillus sp. strains, with multi-metal removal and soil fertility enhancement abilities were isolated. The strain T40 (Bacillus altitudinus) showed the highest potential. Alongside, these strains exhibited effective phosphate solubilization under HM stress. In contrast to most of the previous reports/studies, this work extensively shows the superior potency of halotolerant bacterial strains in multi-metal removal as well as phosphate solubilization under HM stress. Beneficial indigenous bacteria aid in land reformation and also help preserve the original microhabitats, providing a sustainable solution. In the future, these bacterial strains could be applied as biofertilizers to facilitate land transformation and benefit farmers. Thus, this research contributes to the reformation of affected areas, including highly saline, contaminated, or waste lands, as well as mining areas.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

25 soil samples (S1-S25) were collected from several areas of the Sagar Island in the Indian Sundarbans (Co-ordinates given in Supplementary Table 2). Soils were collected from areas named Kirtankhali, North and South Haradhanpur, Digambari, Harinbari, etc. (as shown in Fig. 1). Soil samples were collected aseptically, following random sampling, from crop fields, at a depth of 10–12 cm, and carried to labs in ziplock bags.

Isolation of halotolerant bacteria

In the isolation process, serially diluted soil samples were spread across 2%, 5% and 10% Sodium chloride (NaCl) [Merck, Germany] modified Nutrient agar (Himedia, India) plates. 100 µl of inoculum was taken from three dilution factors- 10− 3, 10− 5, 10− 7. The plates were incubated at 37 ℃ for 24–48 h. Replication was maintained using triplicate for each test variety. Each colony grown on plates was further isolated using 20% NaCl-enhanced NA plates for studying the extent of their salt tolerance.

Screening of HM-resistant halotolerant bacteria

The experiments were conducted following the methods described in Kalaimurugan et al. 202029 and Divakar et al. 201830 with necessary modifications. Stock solutions of Pb (1000 ppm), Ni (1000 ppm), and Cr (3000 ppm) were carefully prepared using Lead nitrate [Pb (NO3)], Nickel chloride [NiCl2], and Potassium chromate [K2CrO4], respectively. The reagents used were sourced from Merck, Germany. Various media solutions were prepared using Nutrient Broth (NB), and HM solutions were added to achieve the desired concentrations. All 50 isolates were screened initially using 50ppm of each of the HMs solutions. Bacterial isolates were grown in these solutions for 48 h at 120 rpm and 37 °C. The growth was assessed by measuring the optical density at 660 nm using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer. The screened isolates were further subjected to increased concentrations of HMs (concentrations increased by 2ppm in each step initially). Through the screening, only three isolates were found that could tolerate > 200ppm of Pb, > 100 Cr and > 70ppm of Ni. The maximum tolerance of the bacteria towards each of the HMs was then further studied.

Determination of MIC

The MIC of the screened isolates for each of the HM was determined using the methods outlined by Maity et al. 202331 and Haroun et al. 201732. The halotolerant strains were inoculated in increasing concentrations (by 2ppm for Ni, 25ppm for each Pb and Cr) of HM in each step. Cr was increased by 100pm in each step for T40 due to its higher tolerance. The culture tubes were kept at 37 °C and 120 rpm for 48 h. The MIC was determined by critically altering HM concentrations by ± 2ppm. Two controls were taken during the MIC determination experiments: Broth + inoculum and NB + HM. The MIC was recorded after confirming the growth of the bacteria at that particular concentration and the absence of growth of the isolate beyond that concentration. Bacterial growth was confirmed by OD600 = 0.5, and growth on NA agar plates (inoculum taken from the cultured tube with respective bacteria and HM). Agar plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C.

Morphological and biochemical characterization of bacterial isolates

Morphological and Biochemical characteristics of the bacterial isolates were observed using methods given in Breed et al. 202233 and Cappuccino 201334.

Molecular identification using 16S rRNA gene sequencing

The genomic DNA of the screened bacterial strains was extracted using a commercial bacterial genome extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers 27 F (5′- AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG − 3′) and 1492R (5′-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) were used in Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) (5 min. 95 °C; 40 s. 95 °C, 40 s. 65 °C, 1.5 min 72 °C for 30 cycles; 10 min. 72 °C)35 for the amplification of 16S rRNA gene. Sequencing was performed using Sanger sequencing, and the sequences were evaluated using MEGA 7 software. The sequences were identified by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), and the phylogenetic tree was generated using MEGA 7 software through maximum-likelihood (MLH) and with 1000 bootstraps. Finally, the acquired sequences were submitted to the GenBank database. All the required kits and chemicals were from Genie Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, India.

Sample preparation and atomic emission spectroscopy (AES) analysis

The samples were prepared following the method described by Wang et al. 202036. In summary, the culture tubes containing Pb, Cr and Ni, at the MIC concentrations of each bacterial isolates, were inoculated with the isolates and kept at 37 °C and 120 rpm for 48 h. After 48 h, the tubes were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were collected and digested using a Block digester with 10 ml of Nitric acid (69%, Molarity = 15.4 M), 4 ml of Perchloric acid (70%, Molarity = 11.6 M), and 1 ml of Sulfuric acid (98%, Molarity = 18.4 M). These acids were obtained from Merck, Germany (Quality grade: Emparta). A control without inocula was maintained for each concentration for each type of HM. The digested samples were filtered through Whatman 42 filter paper and diluted. After filtration, the samples were prepared for analysis using AES (MP-AES, Agilent Technologies, Model: 4210). The HM removal efficiency of each bacterial strain was calculated using the following formula37: Co = initial heavy metal concentration in the solution, Cs = concentration of heavy metal in the solution after treatment with the bacterial isolates.

\({\text{Heavy metal removal efficiency }}={\text{ }}\frac{{{{\text{C}}_{\text{o}}} - {{\text{C}}_{\text{s}}}}}{{{{\text{C}}_{\text{o}}}}} \times 100\%\)

Sample preparation for SEM-EDX analysis

The bacterial strains were prepared for SEM-EDX analysis following the methodology described by Kammoun et al. 202038, with slight modifications as required. Initially, the isolates were allowed to grow in HM-containing NB, where the concentrations of HM varied according to their respective MICs for each of the metals, and in mixture. The tubes were kept incubated at 37 °C and 120 rpm for 48 h. Then, the tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed thrice with Na-P Buffer, and a small amount of the pellet was placed on a glass coverslip. The specimen was fixed using 2.5% Glutaraldehyde for 30 min, and then washed with Na-P Buffer. The slides were then treated with different grades of ethanol: 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and finally absolute alcohol for 10 min each, respectively. The slides were stored at 4 °C until further analysis. All reagents were from Merck, Germany. The samples were then analyzed using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy equipped with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (FESEM-EDX). [FESEM: Hitachi, Japan; Model: SU8010 series]

Biofilm formation and EPS secretion by the isolates

The method outlined in Qurashi & Sabri 201239 was followed to test biofilm production before checking the EPS secretion. The bacterial isolates were grown in Luria Bertani (LB) broth and LB supplemented with the three HMs in their respective MICs in glass tubes. The tubes were inoculated with a culture of 0.5 optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) for 48 h. Later, the tubes were emptied, washed once with distilled water, and treated with a 0.1% aqueous solution of crystal violet for 20–30 min. Purple rings then appeared in the tube walls, and were visible to the naked eye under natural light, post ethanol and distilled water wash.

Further, EPS extraction was conducted according to Senthilkumar et al. 202140 with necessary modifications. Briefly, the bacterial cultures were inoculated in 50 ml of NB and HMs solutions (at their individual MICs’) in 250 Erlenmeyer flasks and kept at 37℃ for 48 h at 100 rpm. After 48 h, the cultures were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, and twice the volume of chilled Isopropanol was added to the supernatant and kept at 4℃ overnight for the precipitation of the EPS. Post incubation, EPS was extracted by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. Afterwards, the pellet was filtered, air dried, and weighed using a Weighing balance (Mettler Toledo New Classic MF ML204) and expressed in g per litre of culture broth. Control with only bacteria in media in the absence of HM and blank with only media were maintained. The content of HM present in the EPS extracted was then measured using MP-AES following the sample preparation and method explained in “Sample preparation and atomic emission spectroscopy (AES) analysis” of this article.

Capability of the bacterial isolates in fixing nitrogen, solubilizing phosphorus, and solubilizing potassium

As the bacterial strains were isolated from crop fields, their efficacy in NPK restoration served as a crucial point. They were tested for their abilities in phosphorus solubilization following zones in insoluble tri-calcium phosphate containing Pikovskaya media as mentioned in Tariq et al. 202241. Similarly the growth of bacterial isolates in Nitrogen-free Jensens’ media proved their nitrogen fixating abilities as shown in Ali et al. 202242 and the formation of yellow zones around the bacterial colonies in Bromothymol blue (2%) added Aleksandrow media confirmed their capabilities in potassium solubilization as given in Rajawat et al. 201643.

Efficacy of phosphate solubilization of halotolerant bacteria under HM stress

The fertilizing abilities of the bacterial strains were tested in the presence of HMs. While nitrogen fixation and potassium solubilization did not yield promising results, phosphate solubilization showed positive results even in the presence of high concentrations of HMs. The method outlined by Aliyat et al. 202244 was used to quantify phosphate solubilization, using NBRIP media with slight adjustments as needed. The media without HM was used as a control, and the test media were supplied with HMs at the different MICs. 50 ml of each type of media was taken and inoculated with 200µL of each isolate. The inoculated media were then incubated at 120 rpm/min for 48 h and subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The soluble phosphate was quantified using the molybdenum blue colorimetric method at a wavelength of 882 nm.

Statistical analysis

All the tests were performed in triplicate. The statistical analysis of one-way ANOVA was done with the help of R software followed by the Tukey HSD test to find significance. The graphs were prepared with the help of MS Excel.

Data availability

Sequence datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository with the Accession numbers (OQ979046, OQ979125 and OQ983889). Data available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OQ979046, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OQ979125 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OQ983889 respectively.

References

Sharma, P. & Pandey, S. Status of phytoremediation in world scenario. Int. J. Environ. Bioremediat. Biodegradation. 2, 178–191 (2014).

Gebeyehu, H. R. & Bayissa, L. D. Levels of heavy metals in soil and vegetables and associated health risks in Mojo area, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 15, e0227883 (2020).

Naman, D. et al. Pollution assessment and Spatial distribution of roadside agricultural soils: a case study from India. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 30, 146–159 (2020).

Kafle, A. et al. Phytoremediation: mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. Environ. Adv. 8, 100203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2022.100203 (2022).

Gupta, N. et al. Evaluating heavy metals contamination in soil and vegetables in the region of North india: levels, transfer and potential human health risk analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 82, 103563 (2021).

Shah, V., Daverey, A. & Phytoremediation: A multidisciplinary approach to clean up heavy metal contaminated soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 18, 100774 (2020).

Pande, V., Pandey, S. C., Sati, D., Bhatt, P. & Samant, M. Microbial interventions in bioremediation of heavy metal contaminants in agroecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 13, 824084 (2022).

Abdel-Razik, M. A., Azmy, A. F., Khairalla, A. S. & AbdelGhani, S. Metal bioremediation potential of the halophilic bacterium, Halomonas sp. strain WQL9 isolated from lake qarun, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 46, 19–25 (2020).

Pagnucco, G. et al. Metal tolerance and biosorption capacities of bacterial strains isolated from an urban watershed. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1278886 (2023).

Tang, H., Xiang, G., Xiao, W., Yang, Z. & Zhao, B. Microbial mediated remediation of heavy metals toxicity: mechanisms and future prospects. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1420408 (2024).

Rebello, S. et al. Bioengineered microbes for soil health restoration: present status and future. Bioengineered 12, 12839–12853 (2021).

Azubuike, C. C., Chikere, C. B. & Okpokwasili, G. C. Bioremediation techniques–classification based on site of application: principles, advantages, limitations and prospects. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32, 180 (2016).

FAO. Global Soil Partnership. Soil Salinity. Oct (2024). https://www.fao.org/global-soil-partnership/areas-of-work/soil-salinity/en/ (accessed 11.

Hassani, A., Azapagic, A. & Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 12, 6663 (2021).

Das, R. S., Rahman, M., Sufian, N. P., Rahman, S. M. A. & Siddique, M. A. M. Assessment of soil salinity in the accreted and non-accreted land and its implication on the agricultural aspects of the Noakhali coastal region, Bangladesh. Heliyon 6, e04926 (2020).

Reang, L. et al. Plant growth promoting characteristics of halophilic and halotolerant bacteria isolated from coastal regions of Saurashtra Gujarat. Sci. Rep. 12, 8151 (2022).

Rahman, S. S., Siddique, R. & Tabassum, N. Isolation and identification of halotolerant soil bacteria from coastal Patenga area. BMC Res. Notes. 10, 531 (2017).

Singh, A. & Singh, A. K. Isolation, characterization and exploring biotechnological potential of halophilic archaea from salterns of Western India. 3 Biotech. 8, 45 (2018).

Kumar, S., Karmoker, J., Pal, B. K., Luo, C. & Zhao, M. Trace metals contamination in different compartments of the sundarbans mangrove: a review. Mar. Pollut Bull. 148, 47–60 (2019).

Etesami, H. & Glick, B. R. Halotolerant plant growth–promoting bacteria: prospects for alleviating salinity stress in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 178, 104124 (2020).

Khumairah, F. H. Halotolerant plant Growth-Promoting rhizobacteria isolated from saline soil improve nitrogen fixation and alleviate salt stress in rice plants. Front. Microbiol. 13, 905210. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.905210 (2022).

Sagar, A. et al. Molecular characterization reveals biodiversity and biopotential of rhizobacterial isolates of Bacillus spp. Microb. Ecol. 87, 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-024-02397-w (2024).

Nayak, B., Roy, S., Mitra, A. & Roy, M. Isolation of multiple drug resistant and heavy metal resistant Stenotrophomonas maltophila strain BN1, a plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, from Mangrove associate Ipomoea pes-caprae of Indian sundarbans. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 10, 3131–3139 (2016).

Mukherjee, P., Mitra, A. & Roy, M. Halomonas rhizobacteria of Avicennia marina of Indian sundarbans promote rice growth under saline and heavy metal stresses through exopolysaccharide production. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1207 (2019).

Das, B. K. et al. Comparative metagenomic analysis from sundarbans ecosystems advances our Understanding of microbial communities and their functional roles. Sci. Rep. 14, 16218 (2024).

Bala, S. et al. Recent strategies for bioremediation of emerging pollutants: a review for a green and sustainable environment. Toxics 10, 484 (2022).

Sharma, P. et al. Recent advancements in microbial-assisted remediation strategies for toxic contaminants. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2, 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clce.2022.100020 (2022).

Al-Mailem, D. M., Eliyas, M. & Radwan, S. S. Ferric sulfate and proline enhance heavy-metal tolerance of halophilic/halotolerant soil microorganisms and their bioremediation potential for spilled-oil under multiple stresses. Front. Microbiol. 9, 394 (2018).

Kalaimurugan, D. et al. Isolation and characterization of heavy metal resistant bacteria and their applications in environmental bioremediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 17, 1455–1462 (2020).

Divakar, G., Sameer, R. S. & Bapuji, M. Screening of multi-metal tolerant halophilic bacteria for heavy metal remediation. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 7, 2062–2076 (2018).

Maity, S. et al. Biofilm-Mediated heavy metal removal from aqueous system by Multi-Metal-Resistant bacterial strain Bacillus sp. GH-s29. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195, 4832–4850 (2023).

Haroun, A. A., Kamaluddeen, K. K., Alhaji, I., Magaji, Y. & Oaikhena, E. E. Evaluation of heavy metal tolerance level (MIC) and bioremediation potentials of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from Makera-Kakuri industrial drain in kaduna, Nigeria. Eur. J. Exp. Biol. 7, 28 (2017).

Breed, R. S., Murray, E. G. & Smith, N. R. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. 10th Ed. (Wiley, 2022).

Cappuccino, J. G. & Sherman, N. Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual. 10th Ed. (Pearson Education Limited, 2013).

Diba, H., Hemmat, J., Vaez, M. & Amoozegar, M. A. Screening of bacteria producing acid-stable and thermostable Endo-1, 4-β glucanase from hot springs in the North and Northwest of Iran. Adv. Res. Microb. Metab. Technol. 1, 23–30 (2018).

Wang, T. et al. Screening of heavy Metal-Immobilizing Bacteria and its effect on reducing Cd2 + and Pb2 + Concentrations in water spinach (Ipomoea aquatic Forsk). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 3122 (2020).

Ghasemi, H., Afshang, M., Gilvari, T., Aghabarari, B. & Mozaffari, S. Rapid and effective removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution using nanostructured clay particles. Results Surf. Interfaces. 10, 100097 (2023).

Kammoun, R., Zmantar, T. & Ghoul, S. Scanning electron microscopy approach to observe bacterial adhesion to dental surfaces. MethodsX 7, 101107 (2020).

Qurashi, A. W. & Sabri, A. N. Bacterial exopolysaccharide and biofilm formation stimulate Chickpea growth and soil aggregation under salt stress. Braz J. Microbiol. 43, 1183–1191 (2012).

Senthilkumar, M., Amaresan, N. & Sankaranarayanan, A. Extraction of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) from Bacteria: Plant-Microbe Interactions. 135–137 (Springer, 2021).

Tariq, M. R. et al. Phosphate solubilizing microorganisms isolated from medicinal plants improve growth of mint. PeerJ 10, e13782 (2022).

Ali, Y., Simachew, A. & Gessesse, A. Diversity of culturable alkaliphilic Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria from a soda lake in the East African rift Valley. Microorganisms 10, 1760 (2022).

Rajawat, M. V. S., Singh, S., Tyagi, S. P. & Saxena, A. K. A modified plate assay for rapid screening of Potassium-Solubilizing Bacteria. Pedosphere 26, 768–773 (2016).

Aliyat, F. Z., Maldani, M., Guilli, E., Nassiri, M., Ibijbijen, J. & L. & Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria isolated from phosphate solid sludge and their ability to solubilize three inorganic phosphate forms: calcium, iron, and aluminum phosphates. Microorganisms 10, 980 (2022).

Diba, H. et al. Isolation and characterization of halophilic bacteria with the ability of heavy metal bioremediation and nanoparticle synthesis from Khara salt lake in Iran. Arch. Microbiol. 203, 3893–3903 (2021).

González Henao, S. & Ghneim-Herrera, T. Heavy metals in soils and the remediation potential of Bacteria associated with the plant Microbiome. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 604216 (2021).

Veluchamy, C., Sharma, A. & Thiagarajan, K. Assessing the impact of heavy metals on bacterial diversity in coastal regions of southeastern India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 828 (2024).

Orji, O. U. et al. Halotolerant and metalotolerant bacteria strains with heavy metals biorestoration possibilities isolated from Uburu salt lake, southeastern, Nigeria. Heliyon 7, e07512 (2021).

Rashed, R. O. & Muhammed, S. M. Evaluation of heavy metal content in water and removal of metals using native isolated bacterial strains. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 22, 810 (2021).

Ramírez, V. et al. Chromium hyper-tolerant Bacillus sp. MH778713 assists phytoremediation of heavy metals by mesquite trees (Prosopis laevigata). Front. Microbiol. 10, 1833 (2019).

Sanuth, H. A. & Adekanmbi, A. O. Biosorption of heavy metals in dumpsite leachate by metal-resistant bacteria isolated from Abule-egba dumpsite, Lagos state, Nigeria. Brit Microbiol. Res. J. 17, 1–8 (2016).

Ameen, F. A., Hamdan, A. M. & El-Naggar, M. Y. Assessment of the heavy metal bioremediation efficiency of the novel marine lactic acid bacterium, Lactobacillus plantarum MF042018. Sci. Rep. 10, 314 (2020).

Ake, A. H. J. et al. Microorganisms from tannery wastewater: isolation and screening for potential chromium removal. Environ. Technol. Innov. 31, 103167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2023.103167 (2023).

Balíková, K. et al. Role of exopolysaccharides of Pseudomonas in heavy metal removal and other remediation strategies. Polymers 14, 4253 (2022).

Budamagunta, V. et al. Nanovesicle and extracellular polymeric substance synthesis from the remediation of heavy metal ions from soil. Environ. Res. 219, 114997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114997 (2023).

Tyagi, B., Gupta, B. & Thakur, I. S. Biosorption of cr (VI) from aqueous solution by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) produced by Parapedobacter sp. ISTM3 strain isolated from mawsmai cave, meghalaya, India. Environ. Res. 191, 110064 (2020).

Concórdio-Reis, P., Reis, M. A. M. & Freitas, F. Biosorption of heavy metals by the bacterial exopolysaccharide FucoPol. Appl. Sci. 10, 6708 (2020).

Gupta, P. & Diwan, B. Bacterial exopolysaccharide mediated heavy metal removal: a review on biosynthesis, mechanism and remediation strategies. Biotechnol. Rep. 13, 58–71 (2016).

Ljubic, V. et al. Removal of Ni2 + ions from contaminated water by new exopolysaccharide extracted from K. oxytoca J7 as biosorbent. J. Polym. Environ. 32, 1105–1121 (2024).

Abo-Koura, H. A., Bishara, M. M. & Saad, M. M. Isolation and identification of N2- fixing, phosphate and potassium solubilizing rhizobacteria and their effect on root colonization of wheat plant. Int. J. Microbiol. Res. 10, 62–76 (2019).

Sagar, A., Yadav, S. S., Sayyed, R. Z., Sharma, S. & Ramteke, P. W. Bacillus subtilis: A multifarious plant growth promoter, biocontrol agent, and bioalleviator of abiotic stress. In Bacilli in Agrobiotechnology. Bacilli in Climate Resilient Agriculture and Bioprospecting (Islam, M.T., Rahman, M. & Pandey, P. eds). (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85465-2_24

Kapadia, C. et al. Evaluation of plant Growth-Promoting and salinity ameliorating potential of halophilic Bacteria isolated from saline soil. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 946217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.946217 (2022).

Naz, H. et al. Mesorhizobium improves Chickpea growth under chromium stress and alleviates chromium contamination of soil. J. Environ. Manage. 338, 117779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117779 (2023).

Kapadia, C. et al. Halotolerant microbial consortia for sustainable mitigation of salinity stress, growth promotion, and mineral uptake in tomato plants and soil nutrient enrichment. Sustainability 13 (15), 8369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158369 (2021).

Hu, X. & Chen, H. Phosphate solubilizing microorganism: a green measure to effectively control and regulate heavy metal pollution in agricultural soils. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1193670 (2023).

Dey, R. et al. Characterization of halotolerant phosphate-solubilizing rhizospheric bacteria from Mangrove (Avicennia sp.) with biotechnological potential in agriculture and pollution mitigation. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 55, 102960 (2024).

Ilyas, N. & et el. The potential of Bacillus subtilis and phosphorus in improving the growth of wheat under chromium stress. J. Appl. Microbiol. 133 (6), 3307–3321. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.15676 (2022).

Sharma, S. B. et al. Phosphate solubilizing microbes: sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. SpringerPlus 2, 587 (2013).

Amri, M. et al. Isolation, identification, and characterization of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria from Tunisian soils. Microorganisms 11, 783 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are obliged to Prof. Arup Bose, Statistics and Mathematics Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, for his expertise. We would like to thank Punjab University (SAIF-Chandigarh) for carrying out the analysis of FESEM-EDX at their facility. Lastly, we are thankful to the Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India, for providing financial support in conducting our research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors Contributions: SM: Writing- original Draft and figure preparation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis. JD: Investigation. SS: Writing- review and editing, visualization. PB: Writing- review and editing, resources, Funding acquisition, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitra, S., Dey, J., Sarkar, S. et al. Halotolerant bacteria isolated from the soils of Indian mangrove ecosystem for metal removal and NPK enhancement. Sci Rep 15, 20804 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07839-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07839-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced nickel bioremediation by mutant strains of Kluyvera cryocrescens M7: a promising approach for environmental remediation

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2025)