Abstract

In the context of birdsong recognition, conventional modeling approaches often involve a significant number of parameters and high computational costs, rendering them unsuitable for deployment in embedded field monitoring devices. To improve the convenience of birdsong recognition, this study proposes a more lightweight model based on the original EfficientNet-B0 architecture. The proposed method introduces the ECA attention mechanism to reduce the parameter complexity while improving feature expression. Furthermore, by adjusting the convolution kernel in the MBConv structure, and incorporating the CBAM attention mechanism in several intermediate layers, we achieve further enhancement in model accuracy. Finally, we employ the Adam optimization algorithm to improve network convergence speed. Our approach attains an impressive 96.04% accuracy in recognizing ten bird species—an improvement of 3.2% over the original model—while reducing parameter count by 16.4%, thereby enhancing both accuracy and convenience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The impact of industrialization and social progress on bird survival has been profound1. There has been a significant decline in bird species diversity, with certain species even facing the threat of extinction. Bird organisms play a vital role in monitoring and preserving the ecological environment2, serving as an indispensable component for maintaining its delicate balance3. Consequently, urgent measures are required to safeguard bird populations. In recent years, researchers have increasingly employed artificial intelligence to aid in the protection of bird species diversity.

Bird recognition plays a pivotal role in bird monitoring, enabling ecologists to conduct more comprehensive ecological assessments and propose targeted conservation measures4. Commonly employed recognition methods are primarily categorized into image-based and sound-based approaches. However, in comparison to bird vocalization-based recognition, image-based recognition is susceptible to the influence of foliage shading and adverse weather conditions5. Meanwhile, Birdsongs play a crucial role in providing essential ecological information, including valuable species identification as each species has distinct songs. Reproductively isolated bird populations demonstrate notable variations in their vocalizations2. Therefore, analyzing birdsong data can offer profound insights into bird species distribution patterns and facilitate the examination of migration trends among bird flocks, serving as a fundamental basis for monitoring ecological environments.

The process of automatic recognition of bird vocalization comprises two pivotal stages: comprehensive feature extraction and subsequent classification of the ascertained vocalizations. The initial step involves extracting acoustic characteristics, which entails mapping the input sound waveform to the domain of feature space. Subsequently, a classification model is then trained using feature vectors, and for identify and categorize the diverse repertoire of birdsongs.

The process of feature extraction involves utilizing a specific model to calculate characteristic parameters that reflect the unique features of bird species present in birdsong signals. This comprehensive procedure typically includes energy features6, time domain features7, and frequency domain features8. Noteworthy audio features commonly employed in this context encompass frequency, amplitude, short-time over-zero rate, spectrogram, waveform, Linear Predictive Cepstral Coefficient (LPCC), Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC), and Short-time energy, among others. In a study by Chen et al.9, successfully extracted time-frequency texture features from birdsong signals, and then used a Random Forest (RF) classifier to accurately recognize 20 different bird species. Deneva et al.10 automatically segmented birdsongs into acoustic events and modeled each segment using a GMM (Gaussian Mixture Model)-based short-term energy interpolation of the dominant frequency components. The resulting segments were then classified to recognize birdsong syllable types. Similarly, Zhang et al.11 employed a GMM to estimate the logarithmic energy distribution of the frames. After applying Mel band-pass filtering to the spectrograms, they used an autoregressive (AR) model to parameterize the output of each subband. This process resulted in a parameterized feature set. Recent multi-view representation learning frameworks, such as the elastic deep autoencoder with diversity embedding12 have demonstrated success in handling heterogeneous data sources. However, their computational complexity limits deployment in resource-constrained scenarios, motivating our focus on lightweight single-view specialization. Li et al.13 used the Inception module to extract multi-scale local time-frequency domain features from the bird song feature map, the CSA module to obtain the global attention weights of the bird song feature map, and finally combined the outputs of the two to obtain a stronger feature map.

Birdsong recognition methods can be broadly categorized into two groups: traditional machine learning-based methods and deep learning-based methods. Traditional machine learning relies on manually extracted feature parameters, with commonly used classification models such as the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) algorithm, Hidden Markov Model (HMM), GMM, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and RF. However, these traditional methods have certain limitations. For example, RF requires spectral statistical information as input, but its computational complexity hampers its application in large-scale bird classification13. HMM is not well-suited for medium and long-term prediction, while SVM faces challenges with large-scale training samples and multiple classification tasks15. Compared to conventional methods, deep learning lies in its robust learning capabilities, which addresses the limitations of manual feature learning and the inadequate generalization ability of traditional methods.

Given the exceptional performance of deep learning models in recognition tasks, they have become the standard approach for birdsong recognition research. In previous studies, CNN has become the main network architecture used.

Incze et al.16 uses CNN for birdsong recognition, going beyond other methods in the LifeCLEF Bird Challenge. In subsequent research, it has been demonstrated that Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) yield superior results in analyzing spectrograms. Qiao et al.17 proposed an RNN-based sequence-to-sequence deep learning method, effectively classifying birdsongs by extracting higher-level features. In time series signals, CNN can be used as the starting point of RNN to get better results. Cakir et al.18 proposed a combined CNN-RNN approach to extract high-dimensional features and short-term inter-frame correlation features from birdsongs, and achieving an impressive results.

With the rapid advancements in various network models, researchers have begun integrating birdsong classification into diverse network architectures to enhance recognition accuracy. For example, Takahashi et al.19 proposed a bird species recognition method employing the VGGNet convolutional neural network model, they coupled it with a data augmentation algorithm and performed recognition experiments on birds from the Xeno-Canto song database using a Softmax classifier. Liu et al.20 introduced a birdsong classification model combining a Bidirectional Long-Short Term Memory (BiLSTM) with a DenseNet convolutional neural network cascade, and utilized Mel-spectrograms as input, achieving an average accuracy rate of 92.2% for 20 bird species. Jeanp et al.21 utilized spectrograms generated by the Short-time Fourier Transform as input to the Transformer neural network after grid processing, yielding high recognition accuracy. Qiu et al.22 employed 128-dimensional VGGish depth features for bird recognition, attaining a recognition accuracy of 94.43% for 38 bird species associated with power grid faults using the pre-trained VGGish transfer learning network from AudioSet.

The preceding studies underscore the prevalent adoption of deep learning models for birdsong recognition, almost of which have yielded positive outcomes. However, previous investigations predominantly employed models characterized by excessive network parameters, larger memory requirements, and intricate structures, rendering them unsuitable for field-based bird recognition devices. Zhang et al.23 introduced a lightweight method is proposed for the classification of bird sound based on continuous frame sequence and spectrogram-frame linear network (SFLN), the mean average precision (MAP) achieves the highest value of 0.97. Wang et al.24 proposed a lightweight point by point depth multi receptive field attention residual network (LPDMR-NET) for bird song recognition, which achieved good results. EfficientNet series model23 demonstrates superior performance and convenience in almost aspects compared to previous CNNs in classification related tasks. Chang et al.26 thoroughly examined various deep learning models to assess their efficacy in birdsong recognition and determined that the EfficientNet network achieves high recognition accuracy with fewer parameters than alternative models.

To further enhance the accuracy and convenience of birdsong recognition, we propose a more lightweight model based on the original EfficientNet-B0 architecture for practical applications in birdsong recognition. The key contributions of this study are outlined as follows:

-

1.

Integrate the characteristics of the ECA attention mechanism, to address information loss caused by compressing high-dimensional features using the SE attention mechanism in the original model structure. This enhancement improves the model’s ability to express information while reducing the number of parameters.

-

2.

Adjusting the kernel size in the convolutional layers further reduces parameters and enhances the model’s discriminative power.

-

3.

Enhancement of the model’s recognition accuracy by incorporating the CBAM attention mechanism in several intermediate layers, leveraging position information that is not included in the ECA attention mechanism.

-

4.

To tackle the slow convergence speed of the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimization algorithm and the issue of convergence to local optima during training, we employ the Adam optimization algorithm to accelerate the model’s convergence.

Research methods

This study presents an improved lightweight method for birdsong recognition by proposing an enhanced EfficientNet-B0 model. The refinement involves the integration of two distinct attention mechanisms, namely ECA and CBAM, achieved through adjustments to the convolution kernel in the model backbone and the modifications to the optimization technique.

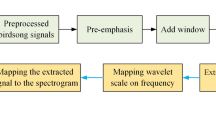

Preprocessing

To improve the accuracy and stability of birdsong recognition, the dataset undergoes preprocessing techniques. This study employs pre-emphasis and frame-windowing as primary techniques. Initially, a high-pass filter is introduced to amplify the amplitude of the high-frequency portion, thereby increasing its energy and enhancing high-frequency features in the birdsong signal spectrum. Subsequently, a Hamming window is applied to interleave frames in the audio, ensuring more reliable and accurate spectral information while eliminating boundary effects. The window calculation can be determined as follows.

where \(\:a\) is the window formula parameter, with a value of 0.46, and N represents the size of the frame. The signal after the addition of the window is given in the following:

where \(\:S\left(n\right)\) is the signal after framing, \(\:n=\text{0,1},\dots\:,N-1\).

Feature extraction

Acoustic classification commonly employs MFCC extraction as a feature extraction method due to its frequency growth aligning with the auditory characteristics of the human ear, and the Mel filter bank accurately simulating the response of the human auditory system23. And based on the characteristics of bird songs, the nonlinear division of the Mel scale in MFCC perfectly aligns with the formant energy range of bird vocalizations (1–8 kHz). As a result, it has found widespread application in studies such as speech recognition and birdsong identification. This paper initially obtains static features using the MFCC method and subsequently derives more dynamic features associated with birdsong through the difference transform. The specific feature extraction steps encompass preprocessing the raw signal with operations like pre-emphasis and frame-windowing. The spectrum of each frame is acquired by applying the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) to each frame post windowing, with the calculation method can be expressed as follows:

where \(\:x\left(f,r\right)\) represents the frequency domain signal,\(\:\:f\:\)denotes the frequency,\(\:\:y\:\)denotes the audio signal of birdsong after pre-weighting,\(\:\:{e}^{-i2fr}\) is the Fourier change factor and\(\:\:r\:\)denotes the frame obtained by STFT of the current window. The power spectrum is processed through M triangular filter banks with of Mel scales, and the resultant Mel-time spectrum is obtained by calculation of the outputs of the M filters. The filter \(\:{f}_{mel}\) can be expressed as follows:

In formula 4, \(\:{f}_{mel}\) represents the calculated Mel scale frequency and \(\:f\) denotes the normal Hertz frequency. The logarithmic transformation yields the logarithmic power spectrum. Subsequently, the energy in distinct frequency bands, post-logarithmic transformation, is reverted to the time domain through DCT to regain the original MFCC. However, these original MFCCs are static features and may not adequately capture dynamic sound signals. To address this limitation, first-order and second-order difference operations are applied, enhancing the temporal information of features in both the front and back frames. This process extracts more dynamic features pertinent to the sound. The differential operation can be determined as follows:

where \(\:\varDelta\:{y}_{x}\) denotes the difference between two consecutive neighboring frames, \(\:x\) denotes the number of frames.

Network model

The EfficientNet network model is a lightweight deep learning model21. Unlike traditional neural network architectures that enhance performance by independently adjusting dimensions such as network depth, channel width, and input image resolution, this model proposes a composite scaling method. A mixing factor, denoted as ϕ, uniformly scales the width, depth, and resolution parameters. The calculation for ϕ is as follows:

where \(\:d\), \(\:w\), and \(\:r\) are width, depth, and resolution, respectively, \(\:\varphi\:\) is the scaling mixing factor, \(\:\alpha\:\), \(\:\beta\:\), and \(\:\gamma\:\) are the corresponding scaling parameters. When ϕ = 1, the most lightweight benchmark model, EfficientNet-B0, can be derived by combining formula (7) with the MNAS (Automated Mobile Neural Architecture Search) method24, utilizing scaling factors of α = 1.2, β = 1.1, and γ = 1.15, respectively. Based on these three proportional coefficients, the B1 to B7 network models are obtained by incrementally varying the mixture coefficient ϕ. In this study, we opt to use EfficientNet-B0 as the benchmark model due to its relatively low parameter count. The model structure of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

ECA attention

In the original EfficientNet-B0 model, each MBConv structure integrates the SE attention mechanism. However, the SE attention compresses high-dimensional feature maps, leading to information loss and impacting the efficacy of channel attention learning. To address these issues, we incorporate the properties of the ECA attention mechanism25. The ECA attention mechanism employs one-dimensional convolution within the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to circumvent dimensionality reduction. This method effectively captures cross-channel interactions, enhancing channel attention and ultimately improving model performance. Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the ECA attention mechanism.

The input features undergo an initial aggregation through average-pooling. Subsequently, a one-dimensional convolution operation is applied to the aggregated features, employing a convolution kernel size denoted as k. Channel weights are generated using the Sigmoid activation function. The resultant output features are obtained by element-wise multiplication of the input features and the channel weights. The formula for adaptive determination of the convolution kernel size is expressed as follows25:

where \(\:{F}_{E}\) is the output feature, \(\:F\) is the input feature, \(\:{\upsigma\:}\) is the Sigmoid activation function, \(\:{f}^{k\times\:k}\) denotes the convolution kernel as a \(\:k\times\:k\) convolution, \(\:\otimes\:\) denotes element-wise multiplication, \(\:k\) denotes the size of the convolution kernel, \(\:C\) denotes the number of channels, and \(\:|{.|}_{odd}\) denotes to take the odd number. \(\:\gamma\:\) and \(\:b\) are set to 2 and 1, respectively, for varying the ratio between the number of channels \(\:C\) and the size of the convolution kernel.

CBAM attention

Given the absence of positional information in the ECA attention mechanism, this study incorporates the characteristics of the CBAM attention mechanism to enhance model performance in the recognition task by augmenting the learning of positional information.

CBAM represents a novel attention mechanism that integrates the Channel Attention Module (CAM) and Spatial Attention Module (SAM) within a convolutional block26. The CBAM attention mechanism assigns distinct weights to various segments of the intermediate feature maps generated by any convolutional neural network in both the channel and spatial dimensions, allowing a focused emphasis on more crucial information. The structure of the CBAM attention is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Within CBAM, spatial information from the feature map is aggregated through average-pooling and max-pooling operations. The resultant input features traverse the channel attention mechanism, producing two feature vectors with distinct spatial contexts. These vectors are subsequently fed into a shared network comprising a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and a hidden layer. Channel attention feature vectors are generated in the channel domain through the Sigmoid activation function applied to the feature attention weights. These weights are then multiplicatively applied to the input features to yield the channel attention feature vector. The corresponding formula is provided as follows26:

where \(\:F\) is the input feature map, \(\:{M}_{c}\left(F\right)\) denotes the computed channel attention weight, \(\:{\upsigma\:}\) denotes the Sigmoid activation function, and \(\:{F}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the weighted channel attention map, \(\:\otimes\:\) denotes element-wise multiplication. The feature vectors for channel attention are subsequently fed into the spatial attention mechanism. Channel information from the amalgamated feature vectors undergoes aggregation using average-pooling and max-pooling, yielding two 2D vectors. Spatial attention weights are computed by applying the Sigmoid activation function to the features extracted using a 7 × 7 convolution kernel. The ultimate feature vectors are acquired by incorporating both feature and location information through element-wise multiplication with F’. The corresponding formula is provided as follows26:

where \(\:{M}_{s}\left({F}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\) is the computed spatial attention weight, \(\:{F}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) is the final feature vector, and \(\:{f}^{7\times\:7}\) denotes the convolution kernel is a 7 × 7 convolution. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the structure of channel attention and spatial attention.

In order to mitigate adverse outcomes, such as suboptimal learning or overfitting, stemming from the inclusion of positional information in either forward or backward positions, the CBAM attention mechanism is integrated into the intermediate layers (layers 3–5) of the MBConv structure within the model backbone. This augmentation enhances the model’s attentional focus.

Regulating the sensory field

The backbone MBConv module of the EfficientNet-B0 model partitions the convolution kernel size k in the DW convolution (Depthwise Convolution) into 3 and 5. Specifically, in the 3rd, 5th, and 6th MBConv modules of the backbone, k is set to 5, while in the remaining modules, k is set to 321. In deep learning models, a larger convolution kernel corresponds to an expanded receptive field. The incorporation of an attention mechanism further amplifies the receptive field size13. However, an excessively large receptive field can compromise the efficacy of the attention mechanism. Consequently, this study modifies the convolution kernel in the DW convolution of the MBConv module. Additionally, to prevent an undue expansion of the receptive field that could undermine the attention mechanism’s effectiveness, all 5 × 5 convolutions are substituted with 3 × 3 convolutions. These adjustments contribute to a notable enhancement in the model’s performance.

Adaptive moment estimation

The original optimization algorithm employed by the EfficientNet-B0 model was SGD. However, it has been observed that SGD converges slowly and often to a local optimum during training, leading to suboptimal recognition models27. To remedy these challenges, this study adopts the Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) optimization algorithm for model training.

Adam is an adaptive optimization algorithm that dynamically adjusts the learning rate based on historical gradient information28. By computing a distinct adaptive learning rate for each parameter, it achieves accelerated convergence and improved generalization. Integrating concepts from RMSProp and Momentum, Adam normalizes parameter updates, ensuring uniform magnitude for each parameter update and thereby enhancing training efficacy.

Experiments and results

Data resources

The study employed two publicly available datasets: the BirdsData dataset, released by BirdsData Technology, and the World’s Wild Bird Sounds dataset obtained from the Xeno-canto website (https://xeno-canto.org). We acquired birdsong audios that corresponded to the BirdsData dataset from the Xeno-canto website and augmented the dataset. To ensure consistency, we employed the Pydub tool to uniformly slice and convert the downloaded birdsong audio data. Subsequently, we processed them into WAV files with a fixed duration of 2 s, aligning with the BirdsData dataset. Detailed information regarding the scientific names, counts, and recording durations of the included bird species can be found in Table 1.

Experimental environment and evaluation metrics

To assess the effectiveness of our proposed model, we conducted experiments on an experimental platform equipped with an Intel i7-13700 F processor, 32GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4070Ti graphics processor. The software environment consisted of a 64-bit Windows 11 operating system, and we utilized PyTorch version 2.0 as our deep learning framework.

To facilitate birdsong recognition across diverse species, we partitioned a dataset of 32,219 birdsong samples into training and test sets at a ratio of 7:3. The training set encompassed 22,553 samples, while the test set comprised 9666 samples. The specific parameters employed in training the model are presented in Table 2.

The model’s classification performance on birds was assessed using accuracy rate, precision rate, recall rate, and F1-Score as evaluation metrics. Accuracy represents the proportion of samples correctly classified by the model to the total number of samples, precision reflects the model’s ability to distinguish between negative samples, while recall indicates the its ability to recognize positive samples. The F1 score is directly proportional to the classification effect, and a higher value indicates an improved effectiveness of the model. Formulas 14, 15 and 16 can be utilized for precision and recall calculations.

where TP denotes the number of correctly predicted positive instances, FP represents the number of incorrectly predicted positive instances, TN denotes the number of correctly predicted negative instances, and FN denotes the number of incorrectly predicted negative instances. The precision and recall obtained can be utilized to calculate the F1-Score, which serves as a comprehensive evaluation metric reflecting the overall performance of a model based on precision and recall rates. The closer the F1-Score is to 1, the better the model’s classification effect. The calculation formula is as follows:

CBAM position and parameters

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of parameters and the specific insertion point for integrating the CBAM attention mechanism on the performance of the model. To achieve this, we conducted experiments on Model-1 (EfficientNet-B0 + ECA + 3 × 3DW convolution), which had already undergone prior improvement.

-

(1)

We tested two values, 8 and 16, for the scaling parameter (r) of the MLP in the CAM of CBAM attention mechanism.

-

(2)

In order to investigate its optimal placement, we incorporated the CBAM attention mechanism into the middle layer of the MBConv structure through two different schemes.

We propose two approaches for the insertion position of CBAM in the intermediate layers. Option 1 focused on replacing all ECA attention mechanisms with CBAM attention mechanisms in the intermediate layer (layer 3–5) of the MBConv structure in the model backbone. Option 2 specifically targeted only the first layer of the ECA attention mechanism within the intermediate layer (layers 3–5) of the MBConv structure in the model backbone.

The experimental results, including recognition accuracy and the number of parameters, are presented in Table 3. Optimal results were achieved with a scaling parameter of 8 and the position described in Option 2. Therefore, for this study, we set the scaling parameter (r) to 8 and incorporated the CBAM attention mechanism into the 3rd to 5th layers of the MBConv structure within the main architecture during the experimental process.

Comparison of the effects of different models

The performance of the models proposed in this study is compared with several popular lightweight deep learning models, including MobileNetV2(2018), MobileNetV3(2019), EfficientNetV2(2021), GhostNetV2(2022), and ShuffleNet(2018). To ensure the scientific rigor and comparability of the experimental results, all models utilized a standardized dataset and were implemented using the Pytorch 2.0 deep learning framework. Each model performed three independent experiments with an epoch of 100, and the highest value among the results was considered as the final recognition accuracy. The experimental results of different models are presented in Table 4.

The experimental results show that the proposed model achieves an accuracy of 96.04%, surpassing other models proposed in the literature. In comparison to the MobileNetV2 model, our model exhibits a performance improvement of approximately 1.43% while reducing the parameter count by 4%. Similarly, when compared to the GhostNetV2 model, our model achieves a remarkable accuracy increase of 3.35% with a reduction in parameters by 31%. Compared to the MobileNetV3 small model and the ShuffleNet model, our model demonstrates an improvement in accuracy by 2.15% and 3.3%, respectively, despite an increase in the number of parameters by 32% and 47%. Furthermore, when compared to the official enhanced version of the EfficientNetV2 small model, our model exhibits an accuracy improvement of 1.42%, accompanied by a reduction in parameter count by 84%.

To comprehensively compare the performance of the models in terms of both accuracy and parameter quantity, this study standardized the two metrics into a unified dimensionless scale and calculated overall scores using weighted averages. Accuracy was transformed to a decimal range from 0 to 10, while the reciprocal of parameter count ranged from 0 to 1. The difference unit between these metrics was set at 0.1 to ensure consistency and scientific calculation in the weighted score. The initial weight ratio of accuracy to parameter count was set at 9:1, which means that accuracy is more important than parameter count in this overall score. Subsequently, the proportion of accuracy was continuously reduced while the proportion of parameter count was increased (from 9:1 to 1:9). Model scores were then obtained for nine groups with different weight ratios. The specific scoring results are depicted in Fig. 6.

The results clearly demonstrate that our model outperforms other models, achieving the highest scores among the top six groups within the nine scoring sets. In the seventh group, our model’s score is comparable to that of MobileNetV3 and ShuffleNet, both of which exceed the scores of the remaining three models. In the last two groups, our model’s score is slightly lower than those of MobileNetV3 and ShuffleNet due to their smaller parameter count. Overall, our model consistently exhibits strong performance across the seven over nine weighted scoring sets, showcasing its ability to effectively adapt to a wide range of requirements.

Figure 7 shows the variation in recognition accuracy of six models over 100 epochs. The accuracy of all models exhibits a gradual increase with the number of iterations. In the initial five rounds, all models, except for EfficientNetV2, demonstrate a faster rate of improvement, resulting in noticeable changes in their respective curves. However, beyond these initial rounds, the improvement curves for each model become less distinct and exhibit fluctuations. Following minor oscillations, the growth rate of accuracy begins to decelerate. By the 55th round, the accuracy curves for each model start to stabilize. The curves of our improved model surpassed those of the other models at the 15th iteration, and from that point onwards, they consistently maintained a significantly higher level until convergence.

To further demonstrate the performance of the proposed model, we conducted a detailed comparison with four state-of-the-art sound recognition methods. All models were trained for 100 epochs, and the best-performing model for each method was selected based on the validation set. Considering the significant impact of hyperparameters on model performance, we used publicly available implementations with default hyperparameters when applicable to ensure fairness in the comparison. The results are shown in Table 5. Experimental results indicate that our model achieved the highest accuracy on the same dataset. Compared to Method 1, our model reduced the number of parameters by 36.6%, while achieving accuracy gains of 4.22%, respectively. Although the parameter count of our model is higher than that of Method 2 and Method 4, the accuracy improved by 3.25% and 0.26%, respectively. When compared to Method 3, our model exhibited a slight increase in parameter count but achieved the highest accuracy improvement of 5.28% among the five models.

Ablation experiment

To evaluate the effectiveness of the various improvements and their impact on the model’s performance, ablation experiments were performed using EfficientNet-B0 as the benchmark model. In the study, only the EfficientNet-B0 benchmark model was utilized, where the SE attention mechanism in the MBConv structure of the EfficientNet-B0 backbone was substituted with the ECA attention mechanism. Additionally, the convolution kernel size of the DW convolution in the MBConv structure was set to 3 for the 3rd, 5th, and 6th layers in the model backbone. Then, the CBAM attention mechanism replaces the ECA attention mechanism in the first layer of the MBConv structure within the middle layer (layers 3–5) of the model backbone. Lastly, based on above modifications mentioned, the Adam optimization algorithm is employed. This study conducted three independent experiments, each comprising 100 epochs, to test various enhancement strategies. The final experimental result was determined by selecting the highest recognition accuracy achieved among these three experiments.

Table 6 shows the experimental results of the methods mentioned above. Method 2, which incorporates the ECA attention mechanism, exhibits a recognition accuracy that is 0.46% higher and utilizes 0.64 M fewer parameters compared to Method 1 employing the SE attention mechanism. This demonstrates the superior efficiency of the ECA attention mechanism in parameter reduction. The experimental results from Methods 2 and 3 indicate that adjusting the convolution kernel of DW convolution to a size of 3 × 3 leads to a notable enhancement in the model’s recognition accuracy by 2.1%, while also effectively reducing the parameter count. This observation suggests that employing DW convolution with a 3 × 3 convolution kernel can efficiently accommodate the ECA attentional mechanism, expand the receptive field, and improve the generalization ability of the model. Consequently, resulting in a significant improvement in recognition accuracy. The comparative results of Methods 3 and 4 demonstrate that the incorporation of the CBAM attention mechanism can improve recognition accuracy with minimal parameter increment, thereby substantiating its efficacy. Furthermore, the results of Methods 4 and 5 (ours) show that the integration of the Adam optimization algorithm can further augment model accuracy. Hence, the proposed improvement scheme in this study is both effective and feasible.

To analyze the classification results of the model, this study utilized a confusion matrix to visualize the test outcomes and assess the model’s effectiveness in classifying each bird species. A confusion matrix, comparing the predicted labels with the true labels, was plotted for 10 classifications, as shown in Fig. 8. The figure illustrates the true label values of the birdsong samples along the rows and the predicted label values along the columns. The color intensity represents prediction effectiveness, with darker shades indicating higher recognition accuracy. Correctly predicted results are predominantly located on the diagonal line within the figure. Moreover, this confusion matrix facilitates efficient calculation of precision, recall, and F1 score for each bird species. Table 7 presents detailed results.

The confusion matrix presented in Fig. 8 reveals that Tringa totanus and Himantopus himantopus exhibited a higher frequency of misclassified predictions and lower F1-scores compared to other species. Both birds were misclassified as each other during the identification process. This misclassification can be attributed to their shared genus Sandpiper, which possesses similar and shorter songs resulting in comparable characteristics, thereby leading to misclassification.

The results presented in Table 7 demonstrate with a precision, recall, and F1-score of 1 for Passer, indicating accurate prediction of all 590 test samples. Anas platyrhynchos and Phasianus colchicus both exhibited a recall of 0.997, with only one misclassified sample each. Anas platyrhynchos was erroneously classified as Phasianus colchicus, while Phasianus colchicus was misclassified as Vanellus vanellus. Both Ardea cinerea and Cygnus cygnus achieved a recall score of 1.000, demonstrating the successful prediction of all true samples, with a precision of 0.999. The confusion matrix reveals that in the case of Cygnus cygnus, a Phalacrocorax carbo was incorrectly classified as Cygnus cygnus, while in the case of Ardea cinerea, a Tringa glareola was misclassified as Ardea cinerea. The precision of 1.000 in the Phalacrocorax carbo sample indicates that the predicted samples for Phalacrocorax carbo are accurate, with a recall of 0.995. The confusion matrix shows three predicted errors in the Phalacrocorax carbo sample, which were classified as Cygnus cygnus, Vanellus vanellus, and Tringa tetanus. In contrast, Himantopus himantopus and Tringa tetanus, belonging to the same genus, exhibited lower scores compared to the other eight species, suggesting that approximately 15% of the samples from both species were misclassified as each other.

In summary, through targeted adjustments to the model’s architecture and the integration of more effective attention mechanisms, we have enhanced its discriminative ability while also achieving a reduction in model complexity.

Model performance experiment

We performed a t-test analysis on the baseline model and ours model to ensure the statistical significance of the experimental comparison. The detailed results are presented in Table 8.

As shown in Table 8, based on the t-statistic calculation method, we obtained a t-statistic of 45.67 and a p-value of < 0.0001, indicating that the accuracy difference between the improved model and the baseline model is highly statistically significant. Additionally, the mean difference is 3.06%, with a confidence interval of [2.91%, 3.21%], further confirming the reliability of the improvement.

we also employed 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate the generalization ability of the model and eliminate potential biases. The detailed results are presented in Table 9. Based on the results in Table 9, we calculated the mean and standard deviation of accuracy, obtaining a mean value of 96.04% (± 0.18% standard deviation). The results indicate that accuracy fluctuates between 95.87% and 96.33% across different folds, demonstrating the strong robustness of the model to varying data partitions. The standard deviation of 0.18% further confirms that the model effectively mitigates overfitting.

Comparison of convergence speeds

To enhance the convergence speed and accuracy of the model, we replaced the original SGD optimization algorithm with the Adam optimization algorithm. We conducted three independent experiments with a fixed epoch of 100 using different strategies. Based on the obtained results, we calculated both the average training time for each model and their corresponding average recognition accuracy.

Table 10 displays the specific experimental outcomes. The results indicate that under different learning rates, the Adam optimizer significantly reduces training time compared to the SGD optimizer. When the learning rate is set to 0.001, Adam achieves the optimal training performance, with an accuracy of 96.04% and a training duration of 809 s. Compared to SGD, the training time is reduced by 28%, 33%, and 37%, while the accuracy is improved by 6.72%, 0.27%, and 0.22%, respectively. Figure 9 presents the error curves for the Adam(lr = 0.001) and SGD(lr = 0.01) optimizers. The figure indicates that as the number of epochs increases, the error curve for Adam converges more rapidly than that of SGD. Furthermore, the error for Adam is smaller when the curve levels off. These experimental results indicate that using the Adam optimization algorithm can enhance convergence speed and improve model recognition accuracy.

Conclusion

This study proposes a lightweight birdsong recognition method based on an improved EfficientNet-B0, aiming to address the current challenges of monitoring birdsongs in field settings and improve the convenience and accuracy of birdsong recognition. The incorporation of the ECA attention mechanism enhances the original model by mitigating the negative impact of the SE attention mechanism on compressing high-dimensional features, thereby enhancing its information expression ability while reducing the number of parameters. Moreover, certain convolutional kernels within the model’s backbone have been refined to prevent large sensory fields from affecting the effectiveness of attention mechanisms, consequently improving its discriminative ability. Furthermore, by incorporating the characteristics from CBAM attention mechanism and introducing positional information to the features, recognition accuracy is further improved. Finally, through utilization of Adam optimization algorithm, convergence speed of the model is enhanced. In comparison to other lightweight models, our proposed model exhibits higher accuracy and relative convenience for recognizing birdsongs in field settings.

Data availability

The code and data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lin, D. L. et al. Taiwan’s breeding bird survey reveals very few declining species. Ecol. Ind. (2023).

Yu, Q., Kun, Q. & Ziping, Z. A survey on Chinese literature for bird sound recognition based on machine listening. J. Fudan Univ. (Nat. Sci.). 59 (02), 375–380 (2020).

Kovaˇr´ık, P. et al. Are birds reliable indicators of most valuable natural areas? Evaluation of special protection areas in the context of habitat protection. Ecol. Ind. 132, 108298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108298 (2021).

Tuncer, T., Akbal, E. & Dogan, S. Multileveled ternary pattern and iterative relieff based bird sound classification. Appl. Acoust. 176, 107866 (2021).

Cai, J. et al. A deep feature fusion-based method for bird sound recognition and its interpretability analysis. Biodivers. Sci. (2023).

Cheng, R. S. & Verdú, S. Capacity of root-mean-square bandlimited Gaussian multiuser channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 37, 453–465 (1991).

Shao, X. et al. Fault diagnosis of bearing based on convolutional neural network using multi-domain features. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 15, 1610–1629 (2021).

Jeong, J. Y. et al. DC series Arc diagnosis based on deep-learning algorithm with frequency-domain characteristics. J. Power Electron. 21, 1900–1909 (2021).

Chen, S. S. & Li, Y. Automatic recognition of bird songs using time-frequency texture. In 2013 5th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks, 262–266 (2013).

Deneva & Prolet and Todor Dimitrov Ganchev. Automatic recognition of the characteristic melody of bird vocalizations. In 2019 International Conference on Biomedical Innovations and Applications (BIA), 1–4 (2019).

Zhiyong, Z. S. Z. Z. et al. Automatic bird vocalization identification based on mel-subband parameterized feature. J. Comput. Appl. 37 (4), 1111–1115 (2017).

Daneshfar, F. et al. Elastic deep multi-view autoencoder with diversity embedding. Inf. Sci. 689 (2025).

Li, H. et al. Bird song classification based on inception CSA deep learning model. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 42 (3), 97–104 (2023).

Koh, C. Y. et al. Bird sound classification using convolutional neural networks. In Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Birdsong classification based on multi feature channel fusion. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81, 15469–15490 (2022).

Incze, Á. et al. Bird sound recognition using a convolutional neural network. In 2018 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Intelligent Systems and Informatics (SISY), 000295–000300 (2018).

Qiao, Y. L. et al. Learning higher representations from bioacoustics: A Sequence-to-sequence deep learning approach for bird sound classification. In International Conference on Neural Information Processing (2020).

Çakir, E. et al. Convolutional recurrent neural networks for bird audio detection. In 2017 25th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), 1744–1748 (2017).

Takahashi, N. et al. Deep convolutional neural networks and data augmentation for acoustic event detection. ArXiv. abs/1604.07160 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Bird song classification based on improved Bi-LSTM-DenseNet network. In 2021 4th International Conference on Robotics, Control and Automation Engineering (RCAE), 152–155 (2021).

Puget, J. F. STFT transformers for bird song recognition. In Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum (2021).

Qiu, Z. et al. Sound recognition of harmful bird species related to power grid faults based on VGGish transfer learning. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 18, 2447–2456 (2022).

Zhang, X. C. el al. Spectrogram-frame linear network and continuous frame sequence for bird sound classification. Ecol. Inform. 54 (2019).

Wang et al. Bird song recognition based on LPDMR-NET. Comput. Eng. 50 (10), 174–184 (2024).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. V. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. ArXiv abs/1905.11946 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Spectrogram-frame linear network and continuous frame sequence for bird sound classification. Ecol. Inf. 54 (2019).

Ganchev, T. D. et al. Comparative evaluation of various MFCC implementations on the speaker verification task. (2007).

Tan, M. et al. MnasNet: Platform-aware neural architecture search for mobile. In 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2815–2823 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 11531–11539 (2019).

Woo, S. et al. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. ArXiv abs/1807.06521 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. A lightweight rice disease identification network based on attention mechanism and dynamic Convolution. Ecol. Inf. 78, 102320 (2023).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. CoRR. abs/1412.6980 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62101114), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (2572021BH02) and Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (LH2023F002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H.: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, visualization, validation, writing-original draft preparation. H.L.: Supervision, writing-reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, H., Luo, H. An improved lightweight method based on EfficientNet for birdsong recognition. Sci Rep 15, 23727 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07875-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07875-w