Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of dietary protein (DP) and lipid (DL) levels on the growth, nutrient retention, and flesh quality of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). A 3 × 3 factorial design was used with three protein levels (28%, 30%, 32%) and three lipid levels (4%, 6%, 8%). Nine experimental diets were fed to fish (initial weight 167.91 ± 0.03 g) for 8 weeks. Results showed significant (p < 0.05) effects of DP and DL on growth performance and flesh quality. The DP28/DL4 diet yielded better growth, feed conversion ratio (FCR), and specific growth rate (SGR) while reducing intraperitoneal fat index (IPFI) and oxidative stress markers. Whole-body chemical analysis indicated higher protein retention (16.65 ± 0.04%) and lower lipid deposition (5.39 ± 0.07%) in the DP28/DL4 group. Flesh quality assessments revealed higher water-holding capacity (WHC), pH, and sensory attributes in DP28/DL4-fed fish. In contrast, higher lipid levels (6–8%) led to increased fat accumulation and oxidative instability. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing DP and DL levels for better growth, nutrient efficiency, and fish quality, supporting sustainable aquaculture and improved production efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus), widely known as Asian catfish, is a freshwater species of considerable economic significance, especially in Southeast Asian countries1,2,3. Owing to its rapid growth, resilience to intensive aquaculture conditions, high consumer preference for boneless fillets, and high export value, this species has become an important candidate species in global aquaculture4,5. Despite its economic importance in aquaculture, it faces quality challenges such as inconsistent texture, high-fat deposition in the muscle and visceral region, suboptimal nutrients, and poor sensory attributes, hindering its export potential6,7,8. Optimised feed formulation caters to industry demands by boosting growth performance, enhancing nutrient utilisation, ensuring good flesh quality to meet consumer expectations, and promoting eco-friendly aquaculture practices9,10. Often, feed formulations are mainly focused on growth and production performance11. However, for this species, fillet quality is a major attribute affecting market demand and price, thereby impacting farmers’income. Consumers now prioritise high-quality, safe, and nutritious food, demanding better sensory characteristics and nutritional profiles12.

Protein and lipid are essential macronutrients in aquafeeds and play pivotal roles in supporting fish growth, body composition, and overall physiological health11,13. Proteins act as fundamental building blocks for muscle development, while lipids serve as a concentrated energy source and provide essential fatty acids critical for various metabolic processes14,15. Optimisation of these nutrients is vital for achieving maximum growth performance and better product quality. Recent studies have focused on the effects of varying dietary protein levels on the growth performance of fry-striped catfish. For example Bano et al.16, demonstrated that a 40% protein diet, formulated using locally sourced ingredients, also improved and significantly enhanced muscle quality in fry-striped catfish. Similarly Lubis et al. 17, demonstrated that different protein levels significantly affected protein and lipid retention in striped catfish. A study by Van Nguyen et al.18 found that incorporating specific oils into the diet of striped catfish juveniles improved growth performance, body composition, and fatty acid profils. Excess dietary protein can increase costs and lead to inefficient utilisation, producing higher nitrogenous waste11,19,20,21. These findings underscore the importance of balancing protein and lipid levels in aquafeeds to achieve desired production outcomes and flesh quality.

The flesh quality is primarily determined by its nutrient composition, including proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates16,17. Studies have highlighted that dietary protein and fat content play a pivotal role in influencing flesh quality22,23. Flesh quality, encompassing factors such as texture, flavor, and nutritional composition, plays a crucial role in determining the market value of fish beyond simple growth metrics24. Sensory attributes such as taste and texture significantly influence consumer acceptance, while biochemical factors such as lipid oxidation and protein content impact both shelf life and nutritional value25. Despite the existing nutritional requirements, there is a need for comprehensive studies that concurrently assess the combined effects of dietary protein and lipid levels on the growth performance, nutrient retention, and flesh quality of growing striped catfish. Such investigations are essential for developing optimised feed and feeding strategies that enhance production efficiency and product quality.

Despite the importance of optimising feed formulations for striped catfish, limited studies have explored the combined effects of protein and lipid on the flesh quality of grow-out pangasius. To address this knowledge gap, a 3 × 3 factorial experiment was designed to investigate the impacts of varying dietary protein and lipid levels on the growth performance and flesh quality of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). The present study integrated sensory and biochemical assessments to offer a holistic view about the influence of dietary nutrients (protein and lipid). The results can guide the development of optimised feed formulations that align with industry standards and consumer preferences, thereby supporting the sustainable growth of striped catfish.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) for the care and use of animals in research. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental diets and design

This study used a 3 × 3 factorial design to investigate the effects of dietary protein (DP) (28%, 30%, and 32%) and dietary lipid (DL) levels (4%, 6%, and 8%) on growth performance and flesh quality of grow-out striped catfish (Table 1). Nine extruded diets (DP28/DL4, DP28/DL6, DP28/DL8, DP30/DL4, DP30/DL6, DP30/DL8, DP32/DL4, DP32/DL6, and DP32/DL8) were prepared. Required ingredients were thoroughly ground and mixed according to the specified formulation (Table 1) to achieve a uniform particle size. The mixture was pre-conditioned and extruded using a single-screw extruder (P98-SANJIVANI, Nagpur, India), producing floating pellets with a diameter of 3 mm. Post-extrusion, the pellets were dried, cooled, and packaged into designated storage bags.

The prepared diets were transported to the experimental site (ICAR-CIFE, Powarkheda, Madhya Pradesh, India) and stored at a cool room temperature until use. The diets were formulated using highly palatable and digestible ingredients at permissible and commercially viable inclusion levels. Key protein sources included oilseed cakes such as deoiled soybean meal (DSBM), groundnut oilcake (GNOC), and mustard oilcake (MOC), alongside high-quality fishmeal (prime grade, TJ Marine Products Pvt. Ltd., Ratnagiri, India). Lipid requirements were met using fish oil and soybean oil (1:1). Deoiled rice bran (DORB), wheat flour, and corn starch served as carbohydrate sources. Additional additives included a vitamin-mineral mixture, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) as binder, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) as antioxidant, and betaine as attractant.

Fish were fed to apparent satiation twice daily, at 08:30 h and 17:30 h, with each feeding session lasting a minimum of five minutes per hapa. Daily feed intake was meticulously recorded to ensure precise data collection.

Experimental fish and conditions

The grow-out striped catfish used in this study were procured from the PRAYAS Fish Farm, Narmadapuram, Madhya Pradesh, India. The acclimatisation period, lasting four weeks, was conducted at the ICAR- Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Powerkheda Centre, Madhya Pradesh, India, within a farm facility (800 m2). During acclimatisation, the fish were fed a commercial diet containing 30% crude protein (CP) and 6% crude lipid (CL). After the acclimatisation period, the experimental fish, with an average initial body weight of 167.91 ± 0.03 g, were starved for 24 h and then randomly distributed to nine treatment groups, each based on a specific experimental diet. Each treatment group consisted of three replicates, with ten fish stocked per m3 / hapa. In total, 27 synthetic nylon mesh hapas [dimensions: 2 m (W) × 3 m (L) × 1.5 m (H), mes h size: 2 mm] were placed in an earthen pond covering 1.1 ha with a depth of 1.6 m. Pond water quality was maintained through partial water exchange using tube-well water, as needed. The hapas were secured with bamboo frames, and mosquito nets were used to cover their tops to prevent fish escape and predation. The feeding trial was conducted for eight weeks.

Water quality parameters

Water quality parameters (except temperature) were monitored twice a week and found within optimal ranges to support the growth of pangasius throughout the study26. The water temperature, recorded daily in the morning and afternoon using a digital thermometer (Eutech Instruments, India), averaged 28.7 ± 1.8 °C, with a range of 27.0 to 30.5 °C. Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels were measured using a DO meter (Lutron DO-5509, Madhya Pradesh, India), with an average of 6.4 ± 0.03 mg L⁻1, ranging from 6.3 to 6.9 mg L⁻1. The pH was measured with a pH meter (Hanna, Amit Engineering Equipments, Indore, India) and remained steady at 7.2 ± 0.13, within a range of 7.1 to 7.4. Additionally, total ammonia nitrogen was recorded with an average concentration of 0.02 ± 0.06 mg L⁻1, ranging from 0.02 to 0.03 mg L⁻1.

Samples collection

Prior to the feeding trial, 4–5 fish were randomly selected and stored at − 20 °C to analyse their initial biochemical composition. After the eight weeks of feeding, all fish were fasted for 24 h before counting and weighing. Sixteen fish were randomly selected from each hapa and anesthetized with MS-222 at a concentration of 350 mg L⁻1. Three fish were preserved whole at − 20 °C for subsequent biochemical analyses. Another three fish were dissected to measure visceral organs, liver, and visceral fat weights, enabling the calculation of indices such as the viscerosomatic index (VSI %), hepatosomatic index (HSI %), gastrosomatic index (GaSI %), intraperitoneal fat index (IPFI %). From the same fish, six dorsal muscle blocks (5–8 g) were collected to evaluate water-holding capacity (WHC) and pH. The remaining ten fish were retained for sensory evaluation and additional biochemical analyses.

Growth performance and nutrient utilisation

The growth performance and body indicators, including weight gain (WG), weight gain percentage (WG%), specific growth rate (SGR), feed conversion ratio (FCR), feed efficiency ratio (FER), protein efficiency ratio (PER), and survival rate (%), were evaluated27 using the following formulas:

Body indices

The following body indices were evaluated using established formulas: hepatosomatic index (HSI), gastrosomatic index (GaSI), intraperitoneal fat index (IPFI), and viscerosomatic index (VSI).

Biochemical composition of feed and fish

The proximate composition of feed and fish was carried out in accordance with28 official method. The moisture content of the samples was determined by oven drying (HAO-9325P; LABLINE Instruments, Mumbai, India) at 105 °C until a constant weight was reached. Total ash (TA) content was assessed by incinerating the samples at 550 °C in a muffle furnace (AI-7982; Sanjeev Scientific, Udyog, Ambala Cantt, India) until a constant weight was obtained. The crude protein (CP) content was calculated using the Kjeldahl method with a nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 6.25, by using a Kjeldahl apparatus (Classic DX VA TS; Pelican Equipments, Chennai, India). Crude lipid (CL) content was determined by Soxhlet extraction with petroleum ether as the solvent, performed using a Soxhlet apparatus (CBNSSP001; Pelican Equipments, Chennai, India). The crude fibre (CF) content was analysed using the FibroTRON (FRB-8, Tulin Equipment, India). The nitrogen-free extract (NFE) content of the diet and the total carbohydrate (TC) content of the whole body were calculated using the following equations27,29:

The contents of CP, CL, TA, and TC were reported on a % wet-weight basis for the fish sample.

Flesh quality indices

Sensory evaluation of muscle

The fish muscle samples were steamed at 100 °C for 5 min and then served on white plates to a panel of 10 trained evaluators from the ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Technology, Kochi, India30. All panel members possessed prior experience in assessing fish-based products. Mineral water was provided to cleanse the palate between tastings to ensure accurate sensory evaluation. The assessments were conducted in a specially designed sensory booth under controlled lighting conditions. The fillet samples were evaluated for key sensory attributes: appearance, colour, odour, taste, flavour, texture, and overall acceptability. A 9-point hedonic scale was used for scoring, where 9 indicated “like extremely”and 1 denoted "dislike extremely”.

Water-holding capacity (WHC) and pH

The water-holding capacity (WHC) and pH of the muscle were measured immediately after fish dissection. The method for calculating the WHC was adapted from31, along with some slight modifications. Approximately 5 g of wet muscle tissue was placed on a Whatman No. 1 filter paper and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. Following centrifugation, the sample was reweighed to determine its weight. The WHC of fish muscle was calculated as follows:

The pH measurement method was adapted from32 using a digital pH meter. To determine the pH, 10 g of homogenized fish muscle was mixed with distilled water in a 1:2 (w/v) ratio, and the measurement was performed using a glass electrode digital pH meter (Testo 205, Germany).

Peroxide value (PV)

A 10% tissue extract in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected for lipid peroxidation analysis. Using a modified IDF33, spectrophotometric method, peroxides were quantified based on their ability to oxidise Fe2⁺ to Fe3⁺. In a 10 mL test tube, 0.1 mL of homogenate was mixed with a chloroform/methanol solution (to 10 mL), followed by 50 μL each of ammonium thiocyanate and Fe2⁺ solutions. After 5 min of incubation in the dark, absorbance at 500 nm was measured against a blank, and the peroxide value (PV) was expressed as milliequivalents of oxygen/kg.

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) content

TBARS content was determined using the method of34. A 10 g fish muscle sample was homogenised with 50 mL distilled water (DW), then mixed with 47.5 mL DW and 2.5 mL 4N HCl (pH 1.5) in a 500 mL round-bottom flask. The mixture was heated, and 50 mL of distillate was collected within 10 min. Then, 5 mL of distillate was mixed with 5 mL of TBA reagent and incubated in a boiling water bath at 100 °C for 55 min. A blank was prepared similarly using DW. After cooling, the absorbance was measured at 538 nm to determine lipid oxidation.

Data analysis and statistics

The data were analysed statistically using SPSS version 25.0. A factorial two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to examine the interaction effects of dietary protein and lipid levels on growth performance, body composition, body indices, and flesh quality in cultured fish. Two-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) was applied to assess the individual effects of dietary protein or lipid levels. If interaction effects were significant, a one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test was conducted to evaluate the influence of one factor on the other. Statistical significance was measured at p < 0.05.

Results

Growth performance and diet utilisation

The two-way ANOVA results (Table 2) demonstrated significant (p < 0.05) effects of dietary protein (DP) on growth performance, nutrient utilization, and flesh quality in striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). In contrast, dietary lipid (DL) had no significant impact (p > 0.05). Notably, a significant interaction effect (p < 0.05) was observed between DP and DL, indicating their combined effect influence on these parameters. DP levels significantly influenced (p < 0.05) growth parameters, including weight gain (WG), specific growth rate (SGR), feed efficiency ratio (FER), protein efficiency ratio (PER), and feed conversion ratio (FCR). All growth parameters were comparable among the 28–30% protein-fed groups. While FCR was lowest in the 28% protein (DP28) fed group, which increased significantly (p < 0.05) in the 30% and 32% protein-fed groups. However, no significant variation in FCR was observed between the DP30 and DP32 fed groups. DL levels did not exhibit any significant (p > 0.05) effect on the growth-related parameters. A significant interaction (p < 0.05) was observed between DP and DL on FBW, WG, WG%, SGR, FER, FCR, and PER. Interaction effects revealed that the effect of dietary protein levels was influenced by lipid levels in the diets as well. Thus, the diet combining DP28/DL4 shows the best growth performance with the lowest FCR.

Tissue somatic indices

Two-way ANOVA indicated that dietary protein (DP) level, dietary lipid (DL) level, and their interaction (DP × DL) significantly (p < 0.05) influenced the body morphometric indices in growing Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Table 3). HSI was significantly affected (p < 0.05) by the dietary protein levels, with lower values in the 28% protein fed group compared to the 30% and 32% protein fed groups. GaSI and VSI remained unaffected significantly (p > 0.05) by protein levels. IPFI was significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the 30% and 32% protein fed groups compared to their 28% counterpart. All body indices showed significant responses (p < 0.05) to varying dietary lipid levels. HSI increased progressively with the increasing lipid levels. GaSI showed the highest values at 8% lipid, followed by 4%, and the lowest at 6%. IPFI and VSI also increased significantly (p < 0.05) with the increasing lipid levels, with substantial changes at each level. A significant (p < 0.05) interaction between DP and DL was observed for all body indices. HSI increased significantly (p < 0.05) with the increasing DP levels, with the highest values observed at 30 and 32%, where values remained statistically comparable. DP and DL in combination had significant effects (p < 0.05) on all response parameters. DP28/DL4 group showed the lowest (p < 0.05) HSI values, while other groups showed non-significant differences (p > 0.05). IPFI was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in DP28/DL8 and lower (p < 0.05) in DP28/DL4 fed group.

Whole body composition

A significant effect (p < 0.05) of dietary protein (DP) and lipid (DL) levels was observed on the whole-body proximate composition of growing Pangasius hypophthalmus (Table 4). The interaction between DP and DL (DP x DL) also significantly influenced (p < 0.05) the whole-body CP and CL contents. Whole body CL content exhibited a significant increase (p < 0.05) with increasing DL levels, reaching a maximum in the DL8 group at DP levels of 30% or 32%. Conversely, lipid content declined when DP was reduced to 28%. Notably, the DP28/DL4 fed group exhibited elevated crude protein content alongside relatively low lipid content in the whole body. Also, DP and DL, individually and in combination, had a significant effect (p < 0.05) on total ash, total carbohydrate, and gross energy content.

Flesh quality indicators

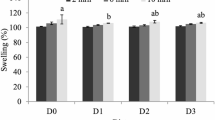

Organoleptic and sensory attributes

Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in fillet organoleptic and sensory profiles across all dietary treatments. Hedonic attributes, as evaluated by consumer preference, are summarised in Fig. 1. Remarkably, fish from the DP28/DL4 fed group showed the highest mean consumer-liking scores. Sensory panel assessments identified statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in the muscle slabs of fish fed various experimental diets. To our knowledge, this study represents the first evaluation of how the varying levels of DP and DL levels impact the sensory properties of grow-out P. hypophthalmus. Irrespective of DP and DL levels, the tested samples were positively characterised by their appearance, texture, flavour, and taste, with no significant negative attributes reported. The most frequently noted attributes regarding appearance were the juicy, moist texture and white flesh observed in the DP28 and DL4-6 treatment groups. Flavour characteristics were predominantly described as fresh, particularly in the DP28/DL4 fed group fish. Texturally, fillets were generally rated as easy to flake, while taste was consistently described as good. Negative sensory descriptors such as musty or earthy odor and taste were minimally perceived and did not reach statistical significance (p < 0.05). Overall, consumer-liking scores were highest for samples from the DP28 and DL4-6 treatment groups, underscoring the favorable sensory attributes associated with these diets.

pH and water-holding capacity (WHC)

The effect of dietary protein (DP) and dietary lipid (DL) levels on the physicochemical properties of Pangasius hypophthalmus flesh was assessed through one-way and two-way ANOVA (Table 5). Two-way ANOVA revealed that DP and DL had a significant effect (p < 0.05) on both pH and WHC. pH was significantly affected (p < 0.05) by protein levels, with higher values in the 32% protein fed group compared to the 28% and 30% groups. WHC was significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the 30% protein group compared to the 28% and 32% fed groups. The individual effect of dietary lipid revealed that pH showed significant variation (p < 0.05) with the highest values in the 4% lipid group, followed by 8% and 6% groups. WHC remained unaffected by lipid levels (p > 0.05). Significant interactions (p < 0.001) were observed between DP and DL for pH and WHC. The DP28/DL4 group showed the highest pH, while DP28/DL8 showed the lowest. WHC was highest in DP28/DL4 and lowest in DP30/DL4. Differences in WHC across treatments were statistically significant (p < 0.05), with lower lipid levels generally associated with increased WHC.

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) of muscle

Varying DP and DL levels had a significant effect (p < 0.05) on the flesh peroxide value (PV) and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) and key lipid oxidation parameters (Table 5). Individual effects of DP and DL were significant (p < 0.05) for both PV and TBARS. PV and TBARS were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the 30% protein fed group compared to other groups. Both PV and TBARS increased significantly (p < 0.05) with increasing lipid levels, except for TBARS, which showed the lowest values at 6% dietary lipid. The DP and DL in combination had a significant effect (p < 0.05) on TBARS, while PV showed no significant change (p > 0.05)). TBARS values were higher in DP30/DL4, DP30/DL8, and DP32/DL8 groups. The DP28/DL4 diet exhibited the lowest PV and TBARS values. In contrast, higher lipid diets, such as DP30/DL8 and DP32/DL6, showed elevated PV and TBARS.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of varying dietary protein (DP) and lipid (DL) levels on growth performance, nutrient utilisation, whole-body proximate composition, and flesh quality of grow-out striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). The findings indicate that dietary protein and lipid levels significantly influence the growth dynamics and flesh quality. The combination of 28% protein (DP28) and 4% lipid (DL4) shows highest WG and SGR along with the lowest FCR, indicating better nutrient utilisation. Further, the diets containing 28% protein and low lipid (4%) levels showed higher or similar growth rates with other treatments while reducing the whole body lipid deposition. The FCR, which measures the efficiency of converting feed into body mass, improved 28% dietary protein but plateaued at a higher inclusion level, suggesting that beyond a certain protein level, the efficiency of feed conversion did not improve further35. On the other hand, the study found that variation in DL levels had no significant impact on growth matrices, indicating that lipid levels alone are not a key factor in determining growth outcomes. These results suggest that optimizing protein and lipid levels in diets promotes maximal growth while minimizing excess fat accumulation, aligning with previous research highlighting the advantages of efficient dietary energy allocation for lean tissue development11. He et al.36 demonstrated that balanced protein and lipid levels improved growth performance and reduced fat accumulation in juvenile Furong crucian carp. Talukdar et al. (2020) reported that optimum dietary protein level with moderate lipid levels improved growth performance along with reduced lipid storage in grey mullets. The study also revealed that dietary lipid levels exceeding 6%, despite increasing energy density, stimulated lipogenesis, and reduced protein utilisation efficiency. This metabolic shift was evidenced by elevated body lipid levels at higher lipid levels. Balanced dietary composition facilitated efficient energy partitioning toward somatic growth rather than lipid deposition, as supported by reduced lipid storage observed in earlier body composition analyses. These findings align with37 reported similar benefits of optimised lipid levels in the diet of tilapia, and38 who found that excessive lipids in black carp diets increased lipid deposition and oxidative stress. Higher lipid diets (DP28/DL6 and DP28/DL8) demonstrated comparable WG but increased FCR and reduced protein utilisation efficiency, inconsistent with studies linking high-lipid diets to suppress protein efficiency due to lipogenesis11,39). The DP28/DL4 diet can be used for improved feed efficiency, reduced environmental impact, and production of high-quality, lean Pangasius for human consumption. The growth results underscore the importance of optimising DP and DL levels to promote efficient growth, minimise lipid accumulation, and preserve flesh quality in striped catfish, providing practical insights for sustainable aquaculture practices.

Both DP and DL levels significantly influenced the hepatosomatic index (HSI), a key marker of liver health and nutrient metabolism. Lower HSI values observed in the low protein and lipid levels, as in DP28/DL4 fed group, indicate reduced hepatic lipid accumulation, suggesting improved energy utilisation efficiency in the group. These results are inconsistent with the findings in Sebastes schlegeli (rockfish), where lower dietary lipid levels enhanced liver health13,40. Gastro somatic index (GaSI) values varied with dietary lipid levels, showing higher values in high-lipid fed group (DP28/DL8). However, the DP28/DL4 fed group exhibited normal GaSI values, indicative of optimised digestive efficiency under moderate protein and lipid levels41. Intraperitoneal fat index (IPFI) increased with higher DL levels and lower protein levels, peaking in DP28/DL8 group. These results indicated lipogenesis and deposition in the peritoneal region because of the higher level of lipids in the DL8 group and higher digestible carbohydrates used in the 28% protein-fed group. Conversely, the DP28/DL4 group showed the lowest IPFI, reflecting reduced visceral fat deposition. Excessive lipid intake led to undesirable fat accumulation, particularly in the abdominal region, corroborating findings from previous studies42,43. The higher viscerosomatic index (VSI) at higher lipid levels indicated that dietary lipid levels showed a more significant influence on visceral fat deposition than dietary protein content. Optimal VSI values in the DP28/DL4 group reflect balanced energy distribution, aligning with studies on Acipenser dabryanus (Yangtze sturgeon), where optimised lipid intake minimised visceral fat deposition44,45. Overall, significant effects were observed for all morphometric indices (HSI, GaSI, IPFI, VSI) with the variation in DP and DL levels, indicating the lipid deposition in striped catfish from dietary lipids and carbohydrates, as both varied in the treatments. Thus, the 28% protein and 4% lipid diet can promote efficient protein utilisation, reduce lipid deposition and maintain physiological homeostasis.

The DP28/DL4 treatment exhibited significantly higher protein retention and energy utilisation efficiency than the other groups. These findings corroborate previous studies suggesting that moderate protein intake and balanced lipid supplementation enhance protein synthesis without inducing metabolic inefficiency46,47. In contrast, as observed in the DP32 groups, excessive dietary protein is often excreted, leading to reduced growth efficiency48,49. This observation aligns with reports by Wang et al.50 who demonstrated similar patterns in lipid deposition with increasing dietary lipid levels, emphasizing the role of dietary lipids in enhancing energy density and lipid storage. However, some earlier researchers have also observed potential risks associated with excessive lipid intake, including hepatic lipid accumulation51. The gross energy values observed in this study suggest that DP28/DL4 facilitates balanced energy distribution without promoting excessive fat deposition. The significantly higher energy levels of the DP28/DL4 fed group appear to stem from the optimal protein-sparing effect. Optimum dietary lipid provide an alternative energy source, allowing dietary protein to be preferentially allocated for growth and tissue repair52,53. Additionally, the significantly lower ash content in the DP28/DL4 fed group than in the DP32 groups indicates reduced mineral wastage, likely due to improved nutrient absorption facilitated by a balanced protein-lipid ratio. Similar observations have been reported in mandarin fish, where a balanced dietary protein-lipid enhanced nutrient utilisation and reduced whole-body ash and mineral content35.

This study demonstrates that DP and DL levels significantly influence sensory characteristics and overall acceptability of Pangasius. Among the treatments, a diet of 28% protein and 4% lipid (P28/L4) showed significantly higher sensory scores, with overall acceptability, outperforming other groups. These results align with those of Iv and Robel54 who reported that moderate protein levels and low lipid content enhance sensory qualities in freshwater fish. The superior texture observed in DP28/DL4 fed fish suggests improved muscle fibre development and protein deposition, consistent with Sankian et al.35 at optimum protein and lipid levels. High taste scores further support the quality of this diet, likely due to improved nutrient utilisation and muscle macro and micronutrient composition. Similar findings in striped bass55 also highlight the benefits of balanced protein-lipid diets for enhancing sensory appeal. In general, higher dietary lipid levels (6% and 8%) resulted in lower sensory scores across all protein concentrations, indicating adverse effects on flesh quality. Excess dietary lipids may impair texture and flavour56,57.

Water holding capacity (WHC) of food is defined as the ability to have its own water or water added through the application of force58. The increased pH and WHC suggest enhanced muscle integrity and water retention, which are critical for the post-harvest quality of fish muscle59,60. Furthermore, fish-fed diets with balanced protein and lipid levels (DP28/DL4) exhibited enhanced WHC, reflecting improved muscle integrity and water retention key parameters for maintaining post-harvest quality56.

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) markers such as PV and TBARS were also estimated from flesh, as these biochemical markers are critical for evaluating the long-term impact of diet on fish health, and flesh quality61. LPO indices also highlighted that the DP28/Dl4 diet showed the lowest value, and the low lipid (4%) and protein (28%) are optimal for maintaining oxidative stability and flesh quality in Pangasius. Lower PV and TBARS values reflect reduced oxidative stress, thereby preserving the nutritional and sensory properties of the fish62. Liu et al.63 found that excessive dietary lipids led to increased oxidative stress and compromised flesh quality in common carp, which parallels the observed trends with higher dietary lipid levels. Conversely56, reported that although higher dietary lipid levels enhanced growth rates in mandarin fish, they also induced oxidative stress, indicated by elevated TBARS levels.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that balanced dietary protein (28%) and lipid (4%) levels (DP28/DL4) optimize the growth performance, nutrient retention, and flesh quality in striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). The DP28/DL4 diet significantly improved feed efficiency, reduced fat deposition, and enhanced sensory attributes, making it a sustainable and cost-effective feed for the aquaculture of striped catfish. Whole-body proximate analysis indicated a synergistic effect of DP and DL on nutrient retention, with DP28/DL4 exhibiting the highest protein retention and minimal lipid deposition. Flesh quality assessments highlighted higher water-holding capacity (WHC), pH, and sensory attributes, including texture, flavour, and overall acceptability of fish fed DP28/DL4. Conversely, higher lipid levels (6%−8%) were associated with increased fat deposition and oxidative instability in the flesh. These findings offer valuable insights for optimizing nutrients for aquafeed formulations to enhance both production efficiency and product quality of Pangasius while meeting the environmental sustainability goals. Future research should explore long-term and species-specific applications to further advance sustainable aquaculture practices.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the findings of this study will be made accessible by the corresponding author, without redundant registration, to any competent scholar.

References

Haque MM Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (sutchi catfish). Identity (2011)

Liu, X. Y., Wang, Y. & Ji, W. X. Growth, feed utilization and body composition of asian catfish (Pangasius hypophthalmus) fed at different dietary protein and lipid levels. Aquac. Nutr. 17, 578–584 (2011).

Suong, N. T. et al. Skeletal deformities in cultured striped catfish Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Sauvage, 1878) in the mekong delta, vietnam. Asian Fish Sci. 36, 85–101 (2023).

Singh, A. K. & Lakra, W. S. Culture of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus into India: impacts and present scenario. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 15, 19 (2012).

Zannat, M. M. et al. An overview of climate-driven stress responses in striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus)–prospects in aquaculture. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res. 9, 70–88. https://doi.org/10.3329/ajmbr.v9i3.66474 (2023).

Belton, B., Haque, M. M. & Little, D. C. Certifying catfish in Vietnam and Bangladesh: Who will make the grade and will it matter?. Food Policy 36, 289–299 (2011).

Little, D. C. et al. Whitefish wars: Pangasius, politics and consumer confusion in Europe. Mar. Policy 36, 738–745 (2012).

Rahmah, S. et al. Aquaculture wastewater-raised Azolla as partial alternative dietary protein for pangasius catfish. Environ. Res. 208, 112718 (2022).

Hassoun, A. et al. Emerging technological advances in improving the safety of muscle foods: Framing in the context of the food revolution 4.0. Food Rev. Int. 40, 37–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2022.2149776 (2024).

Prakash, P. et al. Optimization of weaning strategy in the climbing perch (Anabas testudineus, Bloch 1792) larvae on growth, survival, digestive, metabolic and stress responses. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 49, 1151–1169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-023-01248-8 (2023a).

Routroy, S. et al. Effect of varied levels of dietary protein and lipid on growth response, nutrient utilization, and whole body composition of climbing perch, anabas testudineus (Bloch, 1792) fry. Aquac. Int. 33, 29 (2025).

Aussanasuwannakul, A. & Butsuwan, P. Evaluating microbiological safety, sensory quality, and packaging for online market success of roasted pickled fish powder. Foods 13, 861 (2024).

Li, P. et al. Effects of dietary protein and lipid levels in practical formulation on growth, feed utilization, body composition, and serum biochemical parameters of growing rockfish sebastes schlegeli. Aquac. Nutr. 2023, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9970252 (2023).

Prakash P, Marbaniang BJ, Satheesh M, Baraya RS (2023b) Fish protein hydrolysate (FPH): Excellent protein source for aquafeeds

Singh P, Kesharwani RK, Keservani RK (2017) Protein, carbohydrates, and fats: Energy metabolism. In: sustained energy for enhanced human functions and activity. Elsevier, 103–115

Bano, S. et al. Impact of various dietary protein levels on the growth performance, nutrient profile, and digestive enzymes activities to provide an effective diet for Striped Catfish (Pangasius hypophthalmus). Turk J Fish Aquat Sci 23, 7 (2023).

Lubis, R. A., Alimuddin, A. & Utomo, N. B. P. Enrichment of recombinant growth hormone in diet containing different levels of protein enhanced growth and meat quality of striped catfish (Pangasionodon hypophthalmus). Biotropia 26, 1–8 (2019).

Van Nguyen, N., Hao, P. N., Hai, P. D. & Hung, L. T. Improved growth, body composition, and fatty acid composition in striped catfish juveniles, Pangasianodon hypophthalmus, fed with diets containing different oil sources. J. World Aquac. Soc. 55, e13064 (2024).

Coelho, M. et al. Glycerol supplementation in farmed fish species: A review from zootechnical performance to metabolic utilisation. Rev. Aquac. 16, 1901 (2024).

Mosier, A. R., Syers, J. K. & Freney, J. R. Nitrogen fertilizer: An essential component of increased food, feed, and fiber production. Agric Nitrogen Cycle Assess Impacts Fertil. Use Food Prod. Environ. 65, 3–15 (2004).

Wilson RP (2003) Amino acids and proteins. In: Fish nutrition. Elsevier 143–179

Xu, J. et al. Different dietary protein levels affect flesh quality, fatty acids and alter gene expression of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzymes in the muscle of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture 493, 272–282 (2018).

Zhang, Y.-L. et al. Effects of dietary protein and lipid levels on growth, body composition and flesh quality of juvenile topmouth culter, culter alburnus basilewsky. Aquac. Res. 47, 2633–2641 (2016).

Sant’Ana ASRRR de (2019) Farmed fish as a functional food: fortification strategies with health valuable compounds

Abraha, B. et al. Effect of processing methods on nutritional and physico-chemical composition of fish: A review. MOJ Food Process. Technol. 6, 376–382 (2018).

Da CT, Xuyen BTK, Nguyen TKO, et al Vitamin solutions effects on reproduction of broodstock, growth performance and survival rate of pangasius catfish fingerling (2024)

Mule, S. R. et al. Effect of dietary anabaena supplementation on nutrient utilization, metabolism and oxidative stress response in catla catla fingerlings. Sci. Re.p 14, 27329. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78234-4 (2024).

Aoac C Official methods of analysis of the association of analytical chemists international. off methods Gaithersburg MD USA 2005

Halver JE The nutritional requirements of cultivated warmwater and coldwater fish species. (1979)

David, F. Sensory quality and the consumer: viewpoints and directions1. J. Sens. Stud. 5, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-459X.1990.tb00490.x (1990).

Gómez-Guillén, M. C., Montero, P., Hurtado, O. & Borderías, A. J. Biological characteristics affect the quality of farmed atlantic salmon and smoked muscle. J. Food Sci. 65, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb15955.x (2000).

Fuentes, A., Fernández-Segovia, I., Serra, J. A. & Barat, J. M. Comparison of wild and cultured sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) quality. Food Chem. 119, 1514–1518 (2010).

Standards II (International DF. IDF-Square vergote 41, Brussels. Sec. 74A, 1991 (1991).

Tarladgis, B. G., Watts, B. M., Younathan, M. T. & Dugan, L. A distillation method for the quantitative determination of malonaldehyde in rancid foods. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 37, 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02630824 (1960).

Sankian, Z., Khosravi, S., Kim, Y.-O. & Lee, S.-M. Effect of dietary protein and lipid level on growth, feed utilization, and muscle composition in golden mandarin fish siniperca scherzeri. Fish Aquat. Sci. 20, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41240-017-0053-0 (2017).

He, Z. et al. Effects of dietary protein and lipid levels on the growth performance and serum biochemical indices of juvenile furong crucian carp. Fishes 9, 466 (2024).

Paul, M. et al. Effect of dietary lipid level on growth performance, body composition, and physiometabolic responses of Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT) juveniles reared in inland ground saline water. Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5345479 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. High levels of erucic acid cause lipid deposition, decreased antioxidant and immune abilities via inhibiting lipid catabolism and increasing lipogenesis in black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus). Animals 14, 2102 (2024).

Kutty IM A Study On Protein Sparing Effect Of Dietary Lipids In Labeo Rohita (Pisces: Cyprinidae)

Yan, J. et al. Dietary lipid levels influence lipid deposition in the liver of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) by regulating lipoprotein receptors, fatty acid uptake and triacylglycerol synthesis and catabolism at the transcriptional level. PLoS ONE 10, e0129937 (2015).

Sattanathan G, Venkatalakshmi S (2017) Research article cow urine distillate as an ecosafe and economical feed additive for enhancing growth, food utilization and survival rate in Rohu, Labeo rohita (Hamilton)

Lu, K.-L. et al. Hepatic triacylglycerol secretion, lipid transport and tissue lipid uptake in blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fed high-fat diet. Aquaculture 408, 160–168 (2013).

Naiel, M. A. E. et al. The risk assessment of high-fat diet in farmed fish and its mitigation approaches: A review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 107, 948–969. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpn.13759 (2023).

Azaza, M. S., Saidi, S. A., Dhraief, M. N. & El-Feki, A. Growth performance, nutrient digestibility, hematological parameters, and hepatic oxidative stress response in juvenile nile tilapia, oreochromis niloticus, fed carbohydrates of different complexities. Animals 10, 1913 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Dietary lipid affects growth, feed utilization, liver histology and physiological biochemistry of juvenile Yangtze sturgeon, Acipenser dabryanus, an endangered sturgeon in the Yangtze River. Aquac. Res. 53, 5946–5956. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.16063 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Effects of dietary protein and lipid levels on growth, body composition, enzymes activity, expression of IGF-1 and TOR of juvenile northern whiting Sillago sihama. Aquaculture 533, 736166 (2021).

Rahimnejad, S. et al. Effects of dietary protein and lipid levels on growth, body composition, blood biochemistry, antioxidant capacity and ammonia excretion of European grayling (Thymallus thymallus). Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 715636 (2021).

Siddiqui, T. Q. & Khan, M. A. Effects of dietary protein levels on growth, feed utilization, protein retention efficiency and body composition of young heteropneustes fossilis (Bloch). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 35, 479–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-008-9273-7 (2009).

Yang, S.-D., Liou, C.-H. & Liu, F.-G. Effects of dietary protein level on growth performance, carcass composition and ammonia excretion in juvenile silver perch (Bidyanus bidyanus). Aquaculture 213, 363–372 (2002).

Wang, J.-T. et al. Effect of dietary lipid level on growth performance, lipid deposition, hepatic lipogenesis in juvenile cobia (Rachycentron canadum). Aquaculture 249, 439–447 (2005).

Yin, P. et al. Dietary supplementation of bile acid attenuate adverse effects of high-fat diet on growth performance, antioxidant ability, lipid accumulation and intestinal health in juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquaculture 531, 735864 (2021).

Jin, Y. et al. Interactions between dietary protein levels, growth performance, feed utilization, gene expression and metabolic products in juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture 437, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.11.031 (2015).

Sheridan, M. A. Lipid dynamics in fish: Aspects of absorption, transportation, deposition and mobilization. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Comp. Biochem. 90, 679–690 (1988).

Iv, E. C. & Robel, A. Sensory characteristics of selected species of freshwater fish in retail distribution. J. Food Sci. 58, 508–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1993.tb04312.x (1993).

Nogueda Torres, E. & Lazo, J. P. The effect of protein to lipid ratios on growth, digestibility, and feed utilization of striped bass (Morone saxatilis) raised in seawater at 21 °C. Aquac. Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-024-01639-5 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Effects of dietary lipid and protein levels on growth, body composition, antioxidant capacity, and flesh quality of mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquac. Int. 33, 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-024-01716-9 (2025).

Yu, Y. et al. Recent advances in the effects of protein oxidation on aquatic products quality: Mechanism and regulation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 59, 1968–1978. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.16620 (2024).

Zayas, J. F. Water holding capacity of proteins. In Functionality of proteins in food 76–133 (Springer, 1997).

Ofstad, R., Kidman, S., Myklebust, R. & Hermansson, A.-M. Liquid holding capacity and structural changes during heating of fish muscle: Cod (Gadus morhua L.) and salmon (Salmo salar). Food Struct. 12, 4 (1993).

Swain, S. et al. Significance of water pH and hardness on fish biological processes: A review. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 8, 330–337 (2020).

Ateş M, Çakır Sahilli Y, Korkmaz V Determination of the level of malondialdehyde forming as a result of oxidative stress function in fish 2018

Odour-Odote PM (2020) Effect of natural antioxidants on protein and lipid oxidation in fish (Siganus sutor) processed in a locally fabricated hybrid windmill-solar tunnel dryer. PhD Thesis University of Surrey

Liu, D. et al. Taurine alleviated the negative effects of an oxidized lipid diet on growth performance antioxidant properties, and muscle quality of the common carp. Aquac. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5205506 (2024a).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Director/Vice-Chancellor of ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education (CIFE), Mumbai, which enabled the successful completion of this research. The first author is particularly indebted to ICAR-CIFE for the fellowship received during the study period.

Funding

This research was conducted independently, without external funding from public, private, or non-profit sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Patekar Prakash: Data curation, investigation, software analysis, and original draft preparation. K.N. Mohanta: Conceptualization, supervision, and manuscript review and editing. N.P. Sahu: Experimental design, supervision, and manuscript review and editing. Renuka V: Technical supervision and manuscript review and editing. Tincy V: Chemical analysis and data curation. S.K. Naik: Formal analysis and manuscript review and editing. Ravi Baraiya: Formal analysis and software implementation. Yash Khalasi : Formal analysis and manuscript review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), a regulatory body of the Government of India (approval number: 542/CPCSEA).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prakash, P., Mohanta, K.N., Sahu, N.P. et al. Optimizing dietary protein and lipid levels for better growth performance, nutrient retention and flesh quality of grow-out striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Sci Rep 15, 33874 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07933-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07933-3