Abstract

The increasing global cost of fossil fuels and growing environmental concerns have accelerated the search for sustainable energy alternatives, positioning bioethanol as a promising renewable fuel for spark-ignition (SI) engines. This study uniquely integrates ethanol–petrol blends (E0, E10, E20, and E30) with Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to address critical gaps in predictive modeling and fuel optimization. Experimental tests were conducted on a single-cylinder, four-stroke SI engine under constant load conditions, capturing data on engine speed, mass flow rate, combustion efficiency, peak cylinder pressure, brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC), and exhaust gas temperature. A feed-forward backpropagation ANN model was developed using 75% of the collected data for training and 25% for validation, achieving high predictive accuracy with R2 values exceeding 0.98 for most parameters. Results showed that E30 improved combustion efficiency by 12.5% compared to E0 at 1500 RPM and reduced BSFC by 22% in the 2000–2500 RPM range, while maximum cylinder pressure increased with RPM but remained slightly lower for higher ethanol blends due to ethanol’s cooling effect. By effectively predicting performance metrics across a broad RPM range (1500–3500), the ANN model reduces reliance on extensive experimental testing and offers a scalable approach for optimizing fuel-blending strategies, thereby supporting the transition to cleaner, more efficient energy systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rising fossil fuel costs and environmental urgency are accelerating renewable energy adoption1,2, with bioethanol emerging as a key gasoline alternative for spark-ignition engines. As traditional fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and natural gas become scarcer and more expensive, diversifying energy sources and reducing dependence on these finite resources have become increasingly critical3. Renewable energy, derived from naturally replenishing sources, presents a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative. Technologies like solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and biomass are increasingly adopted, offering clean, reliable, and affordable energy while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating climate change4.

Historically, petrol and diesel engines have relied on fossil fuels, contributing to environmental issues such as air pollution, climate change, and acid rain. The combustion of these fuels releases harmful pollutants, including carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), and particulate matter, which lead to respiratory health problems, smog formation, and ozone layer depletion. Bioethanol has emerged as an attractive alternative for its potential to improve air quality and reduce reliance on fossil fuels in transportation5,6.

Bioethanol, a renewable fuel produced from the fermentation of sugar-rich materials, offers a cleaner and more sustainable alternative to fossil fuels7. Blending bioethanol with gasoline can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve air quality, and enhance energy security3,8. The oxygen content in bioethanol supports more complete combustion, leading to lower emissions of unburned hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide9. While bioethanol has a slightly lower energy density compared to gasoline, its environmental benefits and potential to reduce fossil fuel dependence make it a promising option for both transportation and power generation10,11.

Also, Ethanol, a renewable energy source derived from agricultural biomass such as corn and sugarcane, is gaining popularity as an alternative fuel for spark-ignition (SI) engines12,13. With physical and thermal properties similar to gasoline, ethanol offers a viable option for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and harmful exhaust emissions. Its higher octane rating and oxygen content promote more complete combustion, reducing pollutants like carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), and hydrocarbons (HC)14. However, ethanol’s lower heat of combustion compared to gasoline can result in higher specific fuel consumption, which may affect engine power and torque10,15.

As fossil fuel reserves dwindle and environmental concerns intensify, the demand for alternative fuels like ethanol is growing16. Ethanol, as a liquid fuel, is similar to traditional gasoline and diesel in terms of transportation, storage, and usage. Its oxygenated nature enhances combustion efficiency, making it an attractive option for reducing air pollutants17,18.

Research has demonstrated that ethanol–gasoline blends can improve engine performance and reduce emissions19. Studies have shown that higher ethanol blends, such as E40 and E60, can increase engine torque and reduce exhaust emissions, although they may also lead to higher specific fuel consumption20,21. Other research indicates that mid-level ethanol blends (up to 20%) have minimal effects on combustion rates, while higher blends can further reduce emissions. Additionally, studies suggest that adding ethanol can enhance engine efficiency and reduce emissions, while also increasing engine torque and power, with reduced emissions of CO, NOₓ, and HC22,23.

While bioethanol has been extensively studied as a renewable fuel, research on its effects on engine performance has often relied on experimental approaches or simplified models that fail to capture the complex interactions within internal combustion engines. Existing studies have demonstrated that ethanol–gasoline blends influence parameters such as engine torque, emissions, and efficiency; however, predictive models that accurately quantify these effects under varying operating conditions remain limited24. These parameters are crucial as they directly influence fuel economy, emissions, and overall engine performance19,25. Traditional methods for predicting these parameters are often inadequate for capturing the complex interactions that occur in engine dynamics20,26.

Furthermore, while Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have been increasingly applied in engine performance modeling, many prior studies have focused on conventional gasoline or diesel engines, with relatively fewer applications in bioethanol–fueled engines8,27. The lack of comprehensive ANN-based models trained on diverse ethanol blend ratios and real engine data represents a significant gap in the literature19,28.

This study develops a robust artificial neural network (ANN) model trained on an extensive dataset from a single-cylinder spark ignition engine operating with ethanol–gasoline blends. By incorporating key parameters such as engine speed, torque, mass flow rate, and exhaust gas temperature, the model provides accurate predictions of critical performance metrics, including brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC), combustion efficiency, and cylinder pressure. Unlike previous studies that focused on limited blend ratios or single performance metrics, this work systematically evaluates ethanol content (0–30%) across a broad RPM range (1500–3500), offering a comprehensive approach to fuel blend optimization. Moreover, this study uniquely integrates a broader set of engine parameters and blend ratios, ensuring a more detailed and adaptable predictive model. The ANN framework is also designed to be scalable, making it applicable to different engine types and alternative fuel formulations.

The ANN model is designed to reduce reliance on costly experimental testing by accurately predicting engine performance, making it a valuable tool for optimizing engine design, control strategies, and fuel formulation. Additionally, by capturing the complex relationships between ethanol content, combustion characteristics, and engine operation, this model provides a practical framework for improving efficiency and reducing emissions in ethanol–fueled engines. The ability of ANNs to generalize across different blend ratios and operating conditions further enhances their applicability in real-world scenarios, including engine calibration and emission control strategies.

By bridging the gap between experimental data and predictive modeling, this study advances the use of machine learning in internal combustion engine research. Also, this study distinguishes itself from existing literature by combining a systematic experimental investigation across a broad range of ethanol–petrol blends with an ANN model trained on real-time engine performance data. While previous studies typically focus on limited blend ratios or specific performance indicators, this work presents a comprehensive modeling framework that accurately predicts multiple engine parameters (BSFC, combustion efficiency, and maximum cylinder pressure) under varying RPMs and blend ratios. The novelty lies in the ANN’s ability to generalize across ethanol contents and operating conditions, providing a powerful, data-driven alternative to traditional testing approaches. This dual-layered methodology not only enhances prediction accuracy but also promotes scalable application in engine calibration and emission reduction.

Methodology

This study focused on investigating the performance of a spark ignition (SI) engine using ethanol–petrol blended fuels, with an emphasis on utilizing Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) for predicting engine performance parameters. The methodology is divided into two primary sections: Experimental Setup and ANN Modeling.

Formulas and theoretical framework

The study employed standard thermodynamic and performance equations to analyze engine parameters. Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) was calculated as the ratio of fuel mass flow rate (kg/h) to brake power output (kW), following Heywood’s (2018)29 formulation for internal combustion engine analysis.

Combustion efficiency was determined by comparing actual heat release to the theoretical energy content of the fuel, using the lower heating value (LHV) method as described by Stone (2012)30.

Volumetric efficiency calculations incorporated air mass flow rate, displacement volume, and engine speed according to Ferguson’s (2015)31 engine fundamentals.

For cylinder pressure prediction, the Artificial Neural Network model incorporated engine speed, equivalence ratio, fuel flow rate, and exhaust temperature as key input parameters, following the methodology outlined by Klein (2020)32.

All formulas were implemented in SI units with proper dimensional consistency checks, and experimental measurements were validated against theoretical calculations during preliminary testing to ensure methodological rigor. The ANN predictions were subsequently verified against these standard thermodynamic relationships to confirm the model’s physical validity.

Experimental setup

The experimental setup for this study involved testing various fuel samples using a standardized procedure to measure key engine performance parameters. During the experiments, measurements of engine speed, fuel consumption, exhaust gas temperature, and combustion efficiency were recorded for each fuel type.

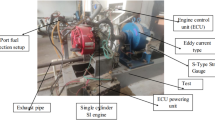

The tests were conducted using a single-cylinder, four-stroke Lifan (177F-B) engine, which was coupled to a brake dynamometer. This engine is an air-cooled, naturally aspirated four-stroke model, with detailed specifications provided in Table 1. Ambient temperature and pressure in the test room were monitored using a thermometer and a barometer, respectively. Combustion efficiency and exhaust gas temperature were analyzed with an exhaust gas analyzer, while fuel consumption per unit time was measured using a calibrated burette and a stopwatch.

Experiments were performed at full throttle with varying engine speeds (full load–constant load tests) using different ethanol–petrol blends.

The objective was to evaluate the engine’s performance under these conditions. The engine was initially started and allowed to idle until it reached normal operating temperature. Subsequently, the throttle was adjusted to a full load position, and the external load on the engine was gradually increased, resulting in changes in engine speed and torque. The engine was first run on neat petrol, followed by various ethanol blends. Before introducing each new fuel blend, the engine was run long enough to consume any remaining fuel from the previous test, ensuring consistency across all trials.

This procedure was applied uniformly for all fuel samples, with measurements of engine speed, fuel consumption, exhaust gas temperature, and combustion efficiency recorded during the experiments.

Materials used in the experiments included the test bed, engine, dynamometer, carburetor, burette, gas analyzer, digital load indicator, stopwatch, thermometer, and thermocouple as depicted in Fig. 1. These tools were essential for accurately measuring and analyzing the performance of the engine under various conditions.

The ethanol–petrol blends (E10, E20, and E30) were prepared by volumetric mixing of anhydrous ethanol (99.7% purity) with commercial unleaded petrol. Each blend was formulated by precisely measuring the required volumes of ethanol and petrol using calibrated cylinders (± 0.5% accuracy), followed by mechanical stirring at 500 rpm for 15 min in an airtight container to ensure homogeneity. To verify stability, the blends were allowed to settle for 24 h before testing, with density measurements (ASTM D4052) and visual inspections confirming the absence of phase separation. Additionally, flashpoint tests (ASTM D93) and octane rating measurements (ASTM D2699) were conducted to validate the fuel properties. To maintain chemical stability throughout the experimental campaign, all blends were stored in temperature-controlled (25 ± 2 °C) opaque containers.

Engine performance parameters—including engine speed, fuel mass flow rate, combustion efficiency, maximum cylinder pressure, brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC), and exhaust gas temperature—were recorded under constant load conditions to ensure consistency. Data collection was performed across a range of engine speeds to capture the engine’s dynamic behavior under varying operating conditions. Exhaust gas analysis was conducted to assess combustion efficiency and emission characteristics for each fuel blend. To minimize experimental errors and enhance data reliability, high-precision sensors, and calibrated instruments were used, as detailed in Table 2.

ANN modeling

This study investigates the application of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to predict engine performance parameters, specifically brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC), combustion efficiency, and maximum pressure. ANNs are powerful tools capable of modeling complex nonlinear relationships, making them well-suited for tasks involving intricate data patterns.

The ANN model utilized mass flow rate, exhaust temperature, bioethanol mixture, and engine speed as input parameters. The target variables were BSFC, combustion efficiency, and maximum pressure. To train and evaluate the ANN model, the dataset was divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. The model was then trained using the training set, and its performance was evaluated on the testing set. While ANNs are effective for complex relationships, other regression techniques such as linear regression, XGBoost, Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Random Forest Regression can also be considered.

This study demonstrates the potential of ANNs for accurately predicting engine performance parameters. By effectively training and implementing the ANN model, valuable insights can be gained to optimize engine operations and improve fuel efficiency.

ANN architecture

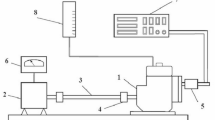

A feedforward backpropagation neural network was employed to model the nonlinear relationships between input parameters (engine speed, mass flow rate, ethanol blend ratio, and exhaust temperature) and output variables (brake-specific fuel consumption, combustion efficiency, and maximum cylinder pressure). The network was implemented in Python using a neural network toolbox for enhanced flexibility and training efficiency.

The architecture consisted of an input layer, one hidden layer, and an output layer. Training was performed using the backpropagation algorithm, with resilient backpropagation proving most effective for convergence. The dataset was split into 75% for training and 25% for validation.

Feedforward neural networks were selected due to their ability to capture complex nonlinear dependencies8. Unlike single-layer networks, which process inputs directly to outputs, multi-layer feedforward networks incorporate hidden layers to extract higher-order features, enabling more sophisticated modeling. Recurrent networks, while useful for sequential data, were unnecessary for this steady-state engine performance analysis. Figure 2 illustrates the multi-layer feedforward structure used in this study, highlighting its input, hidden, and output layers. The feed-forward backpropagation ANN comprised an input layer (4 neurons: engine speed, mass flow rate, ethanol ratio, exhaust temperature), two hidden layers (10 and 6 neurons, respectively, with ReLU activation), and an output layer (3 neurons: BSFC, efficiency, pressure). This configuration was optimized via grid search to minimize MSE.

Data preprocessing

The experimental data was split into training and testing datasets. The training set was used to train the ANN model, while the testing set was used to validate the model’s predictions. Input variables included engine speed, mass flow rate, ethanol–petrol ratio, and exhaust gas temperature. The output variables were BSFC, maximum pressure, and combustion efficiency.

Training the ANN

An ANN must be trained to produce desired outputs in response to a given training set of inputs. This study employed the backpropagation algorithm, a common neural network architecture, for training all models. Backpropagation networks are trained in a supervised manner, utilizing input and output data to minimize network error. This method was applied to most of the ANN models in this study.

Four different training algorithms were evaluated, and all achieved satisfactory results. The resilient backpropagation algorithm demonstrated the highest performance and fastest convergence. These training algorithms can be categorized into three main types: supervised, unsupervised training, and feedforward backpropagation network.

-

A.

Supervised Learning

In supervised learning, the network is trained on a dataset with known inputs and desired outputs. The algorithm adjusts the weights and biases to reduce the error between the predicted and desired outputs, aiming to achieve acceptable network accuracy. The backpropagation algorithm is a widely used supervised learning method for training neural network19.

-

B.

Unsupervised Learning

Unlike supervised learning, unsupervised learning does not require labeled data. Instead, the algorithm identifies patterns and structures within the data without explicit guidance. This is useful when the desired solutions are unknown.

-

C.

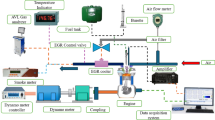

Feedforward Backpropagation Network

The feedforward backpropagation network (Fig. 3), a widely used neural network architecture, comprises an input layer, an output layer, and at least one hidden layer. The backpropagation algorithm, a popular method for training this network, involves several key steps. Initially, input data is propagated through the network during the forward propagation phase, producing predicted outputs. The difference between the predicted and actual outputs is then calculated, which represents the error. This error is subsequently propagated backward through the network in a process known as backpropagation, during which the weights and biases are adjusted to minimize the error10. The algorithm iteratively updates these parameters to improve the network’s performance.

The selection of an appropriate artificial neural network (ANN) architecture depends on the specific problem at hand and the desired outcomes. For this study, Feedforward networks are typically chosen for input–output mapping tasks, making them suitable for a wide range of applications. Recurrent networks, on the other hand, are effective for processing sequential data, such as natural language processing and time series analysis, due to their ability to maintain a memory of previous inputs. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are particularly specialized for image and video processing tasks, as they can capture spatial hierarchies in data through their convolutional layers.

The trained ANN model was validated by comparing the predicted values with the experimental results that were not part of the training dataset. The performance of the ANN was evaluated using statistical metrics such as the correlation coefficient (R2), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). A high correlation coefficient close to 1 indicated a strong correlation between the predicted and actual values.

The ANN model was employed to predict engine performance parameters across various ethanol–petrol blends at different engine speeds, enabling the identification of optimal blend ratios that enhance engine performance while reducing emissions19. By analyzing the discrepancies between predicted and actual values, patterns or inconsistencies were detected, leading to model refinements and improved accuracy. The model’s robustness and generalizability were also assessed by comparing its performance across different fuel blends. This integrated approach, combining experimental data with ANN modeling, offers a cost-effective and time-efficient alternative to traditional methods, providing valuable insights into alternative fuels and engine performance optimization33.

Uncertainty analysis

Experiments and performance parameter calculations are subject to uncertainties arising from environmental conditions, measurement inaccuracies, calibration errors, equipment limitations, and variations in test procedures. To ensure the reliability of the results, an uncertainty analysis was conducted, which confirmed the accuracy of the measurement instruments used in the study. The analysis demonstrated that the experimental data were consistent and reliable, with minimal deviations, supporting the validity of the findings related to combustion efficiency, brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC), and maximum cylinder pressure across different ethanol–petrol blends. This rigorous approach to uncertainty analysis enhances the credibility of the study’s conclusions and ensures that the predictive accuracy of the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model is grounded in precise and dependable experimental data.

Results and discussion

This section presents the performance of the engine when operating on ethanol blends at various engine speeds. Key performance parameters, including combustion efficiency, maximum pressure (combustion pressure), and brake-specific fuel consumption, were evaluated under varying engine speed, mass flow rate, biofuel ratio, and exhaust gas temperature. The results are analyzed to compare the differences in engine performance characteristics between pure gasoline and gasoline-ethanol blends.

Comparison of actual and predicted values

Figure 4 and Table 3 present the comparative analysis of predicted versus actual maximum cylinder pressure (Pmax) values, along with their residual distribution. The experimental Pmax measurements were obtained using a Kistler 6125C piezoelectric pressure sensor, with data collected over 200 consecutive cycles and calibrated to ASTM D6266 standards (± 0.5% FS accuracy). The ANN predictions, generated through a feedforward network (10 neurons in a hidden layer) trained via Levenberg–Marquardt backpropagation, show strong agreement with R2 = 0.996 and MSE = 0.000451. The residual plot reveals a tight clustering around zero, with approximately 24 of the data points concentrated within the − 0.02 to 0.02 bar range, demonstrating the model’s high predictive accuracy. While most predictions fall within this narrow band, minor deviations (ranging from − 0.08 to 0.06 bar) occur primarily at higher RPMs, likely due to ethanol’s cooling effect not being fully captured in the training data. This pattern is consistent with the slight overprediction (0.1–0.2 bar) observed in Fig. 4's comparison plot. The combined evidence from both the residual distribution and direct prediction-actual comparison confirms the ANN’s robustness in estimating Pmax, particularly in the optimal mid-RPM range (2000–2500 RPM), while identifying specific operational conditions where future model refinements could enhance accuracy, as evidenced by the tight clustering of residuals around zero.

All models demonstrated strong performance in predicting maximum pressure, with consistently high R2 scores and low mean squared error (MSE) values. Among the models, Support Vector Regression (SVR) achieved the highest R2 score and the lowest MSE, indicating superior predictive accuracy for maximum pressure. Figure 5 and Table 4 illustrate the distribution of residuals between the predicted and actual Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) values generated by the regression model. The residual distribution is centered around zero, indicating that the model’s predictions are generally unbiased. The majority of residuals fall within a narrow range of − 0.005 to 0.005, suggesting that the model’s predictions are highly accurate. However, a slight skew towards negative residuals is observed, indicating a systematic tendency for the model to overestimate BSFC. This minor bias suggests that while the model performs well overall, further refinement could improve its accuracy, particularly in minimizing overestimation errors.

In addition to traditional evaluation metrics such as R2 and MSE, the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) was also calculated to further assess model accuracy. For maximum pressure prediction, the MAPE was found to be 1.23%, indicating that the ANN model’s estimates are within a narrow margin of the actual values. Confidence intervals at the 95% level were also computed using bootstrapping techniques, which revealed that most predicted values fell within ± 2% of the actual measurements. These additional metrics reinforce the model’s robustness and its applicability in real-world engine performance prediction scenarios.

XGBoost and Random Forest again demonstrated strong performance for BSFC prediction, with high R2 scores and low MSE. Linear Regression underperformed compared to the other models.

Figure 6 and Table 5 illustrate the error distribution between the predicted and actual combustion efficiency values obtained from the regression model. The error values are predominantly centered around zero, signifying that the model exhibits high predictive accuracy. However, a discernible positive bias is observed, with a peak around + 1, indicating a tendency of the model to overestimate combustion efficiency. The strong agreement between the predicted and experimental results suggests that the developed neural network model effectively captures and generalizes the underlying relationship between the input and output variables..

The XGBoost and Random Forest models exhibited superior performance, with R2 scores close to 1 and low mean squared errors (MSE). Linear Regression, while achieving reasonable accuracy, demonstrated a significantly higher MSE compared to the other models.

Among the three target variables, combustion efficiency showed the highest predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.998 with Random Forest), followed by maximum pressure (R2 = 0.996), and BSFC, which had the lowest R2 at 0.979 using XGBoost. These results indicate that the model performs best in predicting combustion-related metrics and slightly less accurately for fuel consumption, likely due to its higher sensitivity to dynamic engine conditions.

In conclusion, the analysis of the regression models for combustion efficiency, maximum pressure, and Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) demonstrates that the models, particularly the XGB and Random Forest Regressors, deliver highly accurate predictions with minimal errors. The selection of a 100-epoch training regime was validated by a significant reduction in prediction errors, as shown in the epoch analysis Figs. 4, 5 and 6. Overall, the models exhibit strong generalization capabilities, providing reliable predictions across various parameters.

Error and epoch number for both training and validation

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between the error, measured as Mean Squared Error (MSE), and the number of training epochs for a model predicting Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC). The graph features two lines representing the training error and validation error across 20 epochs.

The blue line, representing the training error, begins at a relatively high MSE of approximately 0.5 and decreases rapidly during the first few epochs. This sharp decline indicates that the model is learning effectively in the early stages of training. After about five epochs, the rate of decrease slows, and the training error gradually approaches a plateau, stabilizing around 0.05 MSE by epoch 20. This behavior suggests that the model is converging and reaching its optimal performance on the training data.

The orange line, representing the validation error, remains consistently low throughout the training process, starting below 0.05 MSE and showing minimal fluctuation across all epochs. The stability of the validation error indicates that the model is generalizing well to unseen data and is not overfitting. Unlike the training error, which decreases over time, the validation error does not exhibit significant changes, further confirming the model’s robustness.

The MAPE for BSFC prediction was 2.1%, and for combustion efficiency, it was 1.67%, demonstrating the ANN model’s reliability across different output parameters. Confidence intervals showed narrow prediction bands, supporting its use in the practical optimization of ethanol–fueled engines.

Overall, the graph suggests that the model is effective at predicting BSFC. The significant reduction in training error, combined with the stable and low validation error, demonstrates that the model learns well from the data while maintaining its generalization capability. The absence of an increase in validation error indicates that the model avoids overfitting, making it reliable for predicting BSFC on new data.

Figure 8 illustrates the convergence behavior of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) as a function of training epochs for both the training and validation datasets in the prediction of maximum pressure. At the outset (epoch 0), the MSE for the training set is observed to be slightly above 600, while the validation set exhibits a slightly lower MSE near 550. This indicates that the initial model configuration, likely with randomly initialized weights, results in a high error for both datasets.

A rapid decrease in MSE is observed during the initial phase of training. Specifically, between epoch 0 and epoch 5, there is a significant drop in the error values for both datasets. By the fifth epoch, the training error reduces to approximately 30 MSE, while the validation error decreases to around 50 MSE. This steep decline in error suggests that the model quickly learns the underlying patterns in the data within the first few epochs.

After the initial phase, the errors for both training and validation datasets stabilize, indicating a convergence point. Post epoch 5, the MSE values for both datasets exhibit minimal fluctuation, with the training error stabilizing around 20–30 MSE and the validation error consistently hovering between 30 and 50 MSE. The close proximity of these error values post-convergence is indicative of a well-trained model with limited overfitting.

The convergence of the training and validation errors is particularly noteworthy, as it suggests good generalization capability of the model. The small and stable difference between the training and validation MSEs after the initial learning phase indicates that the model maintains consistent performance across both datasets. This balance is crucial in ensuring that the model is not only fitted well to the training data but also performs reliably on unseen data, which is critical for real-world applications.

Figure 9 depicts the evolution of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) across 25 epochs for both the training and validation datasets, with the aim of evaluating a model’s performance in predicting combustion efficiency. Initially, at Epoch 0, the MSE for both the training and validation datasets is observed to be approximately 4000, indicating that the model starts with a significant degree of error, likely due to its initial underfitting state where it has yet to learn the underlying patterns in the data.

As training progresses, a marked decrease in error is observed over the first five epochs. Specifically, by Epoch 1, the MSE drops to around 1000 for both datasets, signifying a rapid improvement in the model’s learning process. This trend continues until about Epoch 5, where the MSE for both training and validation datasets converges to approximately 50. This sharp reduction in error highlights the model’s ability to quickly adapt and improve its predictions during the early stages of training.

Beyond Epoch 5, the MSE values for both datasets stabilize, hovering around 50 MSE through to Epoch 25. The close alignment of the training and validation errors throughout this period suggests that the model has not only learned effectively but is also generalizing well to unseen data, as evidenced by the absence of significant overfitting. The low and stable error rates post-Epoch 5 indicate that further training is unlikely to yield substantial improvements, implying that the model has reached an optimal point in its training process.

In conclusion, the model exhibits robust learning dynamics, characterized by a rapid decrease in error during the initial epochs followed by stable performance, with minimal difference between training and validation errors. This performance profile is indicative of a well-calibrated model that balances both accuracy and generalization, making it suitable for predictive tasks in the context of combustion efficiency.

Effects of biofuel blending ratios

Performance of pure gasoline (E0)

Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between engine RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) and combustion efficiency for a fuel mixture composed of 0% ethanol and 100% petrol, referred to as bio-fuel ratio E0. The plot compares the actual combustion efficiency (blue line) with the predicted combustion efficiency (orange line) across an RPM range of 1500–3500.

At the lower RPM of 1500, the actual combustion efficiency starts at approximately 65%. As the RPM increases, a linear decline in combustion efficiency is observed, with the actual efficiency dropping to around 58% at 3500 RPM. This inverse relationship between RPM and combustion efficiency is expected, as higher RPMs typically result in reduced combustion efficiency due to increased engine speed and associated losses.

The predicted combustion efficiency follows a similar downward trend but consistently overestimates the actual values across the RPM range. For example, at 1500 RPM, the predicted efficiency is approximately 66%, slightly higher than the actual value. By 3500 RPM, the predicted efficiency decreases to around 59%, maintaining a consistent margin above the actual efficiency curve. This systematic overestimation suggests that while the prediction model captures the overall trend of decreasing efficiency with increasing RPM, it exhibits a consistent bias in its predictions.

In summary, the model provides a reasonable approximation of combustion efficiency for the E0 bio-fuel ratio across varying RPMs. However, it systematically overestimates the actual values by approximately 1% to 2% throughout the range. This indicates the model’s potential for predicting combustion efficiency trends but also highlights the need for refinement to improve accuracy, particularly in addressing the overestimation bias.

Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between engine RPM and maximum pressure for a bio-fuel ratio of E0 (0% ethanol and 100% petrol). The graph compares actual maximum pressure values, indicated by the blue line, with the predicted maximum pressure values, shown by the orange line, over an RPM range from 1500 to 3500.

Numerically, at the lower RPM of 1500, the actual maximum pressure is approximately 26.8 bar. As the RPM increases, the maximum pressure also rises, displaying a positive correlation between RPM and pressure. By 2500 RPM, the actual maximum pressure reaches around 28.0 bar, showing a rapid increase in pressure with increasing RPM. Beyond 2500 RPM, the rate of increase in pressure slows down, with the maximum pressure gradually leveling off around 28.1 bar as the RPM approaches 3500.

The predicted maximum pressure follows the same general trend as the actual data, closely matching the actual values across most of the RPM range. At lower RPMs (e.g., 1500), the predicted pressure is nearly identical to the actual pressure, indicating high accuracy in the model’s predictions. However, slight deviations are observed as RPM increases. For instance, at 2500 RPM, the predicted pressure slightly exceeds the actual pressure by about 0.1 bar. This minor overestimation continues at higher RPMs, where the predicted pressure remains slightly above the actual pressure.

Overall, the model demonstrates strong predictive performance, accurately capturing the increasing trend of maximum pressure with RPM. The minor overestimation observed at higher RPMs is minimal, suggesting that the model is well-calibrated but could benefit from slight adjustments to eliminate the small bias in predictions. Despite these slight discrepancies, the predicted values are in close alignment with the actual data, underscoring the model’s reliability in predicting maximum pressure for the E0 bio-fuel ratio across a range of engine speeds.

Figure 12 presents the variation in Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) across different engine speeds, demonstrating the correlation between actual and predicted values. At lower RPMs (1500–2000 RPM), BSFC decreases from approximately 0.315–0.300 kg/kWh, with the predicted values closely mirroring this trend. This decline indicates improved combustion efficiency due to enhanced fuel–air mixing and increased in-cylinder turbulence.

In the mid-RPM range (2000–2750 RPM), BSFC continues to decrease, reaching a minimum of approximately 0.255 kg/kWh at 2500 RPM. The predictive model accurately captures this trend, indicating that it effectively accounts for key engine parameters such as volumetric efficiency, combustion dynamics, and heat transfer. However, beyond 2500 RPM, a slight increase in BSFC is observed due to rising pumping and frictional losses, with minor deviations between actual and predicted values. At higher RPMs (2750–3500 RPM), BSFC rises, peaking at approximately 0.315 kg/kWh at 3250 RPM before slightly decreasing. The model follows a similar pattern but slightly underestimates BSFC, likely due to unmodeled high-speed dynamic effects such as valve float, turbulence variations, and mechanical losses.

Overall, the predictive model provides a reliable approximation of BSFC across various RPM ranges, with minor discrepancies at higher speeds. The analysis highlights that optimal engine efficiency occurs around 2500 RPM. These findings are valuable for optimizing fuel economy and calibration in internal combustion engines operating on pure petrol (E0).

Performance of E10 blend (10% Ethanol, 90% Gasoline)

Figure 13 illustrates the relationship between engine speed (RPM) and brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC) for an internal combustion engine operating on a biofuel blend (E10). The figure presents actual BSFC values with error bars, indicating measurement uncertainties due to sensor inaccuracies, combustion variations, and transient effects, alongside predicted BSFC values, represented as a smooth red curve. The x-axis spans 1500–3500 RPM, while the y-axis captures BSFC variations from approximately 0.22–0.34 kg/kWh. At lower RPMs (1500–2000 RPM), actual BSFC starts around 0.32 kg/kWh and gradually decreases with increasing engine speed, suggesting improved efficiency due to enhanced turbulence and fuel–air mixing. The predicted BSFC closely follows this trend but slightly underestimates actual values, likely due to unaccounted low-speed combustion inefficiencies such as incomplete atomization and higher heat losses. In the mid-RPM range (2000–2750 RPM), BSFC continues to decline, reaching a minimum of approximately 0.24 kg/kWh at 2500 RPM. This marks the engine’s optimal efficiency zone, where combustion efficiency, volumetric efficiency, and mechanical losses are balanced. The predicted BSFC aligns well with actual values in this region, capturing key performance characteristics.

Beyond 2750 RPM, BSFC increases, peaking at approximately 0.31 kg/kWh at 3250 RPM before slightly decreasing at 3500 RPM. The predicted BSFC follows this pattern but remains marginally lower than actual values. This rise in BSFC at higher speeds is attributed to increased frictional losses, reduced volumetric efficiency, and heat rejection, alongside shorter combustion durations that reduce thermal efficiency.

The error bars highlight the variability in actual BSFC measurements, reflecting fluctuations in fuel injection, cycle-to-cycle combustion variations, and sensor-related uncertainties. While the model effectively captures BSFC trends, slight underestimations at higher RPMs suggest the need for refinements incorporating high-speed combustion dynamics, frictional losses, and transient effects to enhance accuracy.

Figure 14 illustrates the relationship between engine RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) and maximum pressure for an engine running on an E10 bio-fuel blend (10% ethanol and 90% petrol). The data presents both actual measured values and predicted values derived from a model, offering insight into the accuracy of the predictive model under varying operational conditions.

The observed trend in the graph is a linear increase in maximum pressure as the RPM increases, indicating that the engine’s pressure response to higher rotational speeds is consistent and predictable. At lower RPMs, specifically around 1500 RPM, the maximum pressure recorded is approximately 27.0 bar. As the engine speed increases, there is a corresponding rise in pressure, reaching around 28.4 bar at 3500 RPM. This linear progression suggests that the engine operates efficiently across the tested RPM range, maintaining a stable increase in pressure.

The close alignment between the actual and predicted pressure curves is noteworthy, demonstrating the high accuracy of the predictive model. The maximum deviation between the two curves is minimal, reinforcing the reliability of the model in replicating real-world engine performance. Such accuracy is essential for validating the model’s utility in predicting engine behavior, which can be critical for optimizing engine designs or tuning engines for different bio-fuel compositions.

Moreover, the stable performance of E10 fuel, as indicated by the linear pressure response across varying RPMs, underscores its suitability as an alternative to pure petrol. The bio-fuel’s predictable behavior ensures that it can be used without compromising engine performance, making it a viable option for reducing reliance on fossil fuels while maintaining engine efficiency.

In conclusion, the graph effectively demonstrates that the engine’s maximum pressure behavior with E10 bio-fuel can be accurately predicted across a range of RPMs. The high degree of correlation between actual and predicted values validates the predictive model’s accuracy and highlights the potential of E10 as a stable and efficient fuel for internal combustion engines.

Figure 15 illustrates the relationship between engine RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) and Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) for an engine operating on an E10 bio-fuel blend, consisting of 10% ethanol and 90% petrol. Both actual measured BSFC values and those predicted by a computational model are plotted, providing a comparative analysis of the engine’s fuel efficiency across a range of operational speeds.

At lower RPMs, specifically around 1500 RPM, the BSFC is observed to be relatively high, approximately 0.315 kg/kWh. As the RPM increases, there is a notable decrease in BSFC, reaching a minimum of about 0.265 kg/kWh at approximately 2500 RPM. This decline in BSFC indicates that the engine’s fuel efficiency improves significantly as the RPM increases up to this point, reflecting a more efficient conversion of fuel into mechanical energy.

The engine achieves its highest efficiency between 2250 and 2500 RPM, where the BSFC is at its lowest. This range represents the optimal operating condition for the engine, where the fuel consumption per unit of power output is minimized. The close alignment between the actual and predicted BSFC values within this range suggests that the predictive model is highly accurate in capturing the dynamics of the engine’s fuel efficiency.

However, as the RPM continues to increase beyond 2500, the BSFC begins to rise again, reaching approximately 0.295 kg/kWh at 3500 RPM. This trend indicates a decrease in fuel efficiency at higher engine speeds, likely due to increased mechanical losses and the higher fuel demand required to maintain elevated power outputs. The upward trend in BSFC at higher RPMs underscores the trade-off between engine speed and fuel efficiency.

The predicted BSFC values closely follow the actual measurements across the entire RPM range, with only minor deviations. This consistency reinforces the reliability of the predictive model, making it a valuable tool for optimizing fuel consumption in engines using bio-fuel blends. The model’s accuracy in predicting BSFC under varying operational conditions is critical for further studies focused on improving engine performance and reducing fuel consumption.

In conclusion, the graph provides valuable insights into the BSFC behavior of an engine fueled by an E10 bio-fuel blend. The observed trends highlight the engine’s optimal operating range and the impact of increasing RPM on fuel efficiency. The strong correlation between actual and predicted BSFC values validates the predictive model’s utility, offering a robust framework for future research and development in engine optimization and biofuel utilization.

Performance of E20 blend (20% Ethanol, 80% Gasoline)

Figure 16 presents the relationship between engine RPM and combustion efficiency for a bio-fuel mixture of E20 (20% ethanol and 80% petrol). The plot compares actual combustion efficiency, indicated by the blue line, with predicted combustion efficiency, represented by the orange line, over an RPM range from 1500 to 3500.

At the lower RPM of 1500, the actual combustion efficiency is approximately 78%, which is relatively high. However, as the RPM increases, a clear negative correlation is observed, with the combustion efficiency declining steadily. By the time the RPM reaches 3500, the actual combustion efficiency has decreased to around 70%. This decline is expected as higher engine speeds often lead to less efficient combustion processes due to increased heat losses and incomplete combustion events.

The predicted combustion efficiency follows a similar downward trend but consistently underestimates the actual efficiency values across the RPM range. For instance, at 1500 RPM, the predicted efficiency is around 76%, which is about 2% lower than the actual value. As RPM increases, this trend of underestimation persists; at 3500 RPM, the predicted efficiency is approximately 69%, which still maintains a slight deviation from the actual values observed throughout the range. The consistent underestimation suggests that while the model accurately captures the overall trend of decreasing efficiency with increasing RPM, it does so with a bias that leads to lower predicted values compared to the actual measurements.

In summary, for the E20 bio-fuel ratio, the model effectively captures the trend of decreasing combustion efficiency with increasing RPM but consistently underestimates the efficiency by a margin of about 1–2%. This systematic bias indicates the model’s general reliability for trend prediction, though adjustments may be necessary to enhance accuracy and bring predicted values closer to actual data. Despite these discrepancies, the alignment of the trend lines suggests that the model’s predictions are useful for understanding the general behavior of combustion efficiency across varying RPMs for bio-fuel mixtures with ethanol content.

Figure 17 illustrates the relationship between engine RPM and maximum pressure for a bio-fuel mixture of E20 (20% ethanol and 80% petrol). The graph compares actual maximum pressure values, represented by the blue line, with predicted maximum pressure values, indicated by the orange line, over an RPM range from 1500 to 3500.

At the lower RPM of 1500, the actual maximum pressure starts at approximately 27.1 bar. As RPM increases, there is a consistent and nearly linear increase in maximum pressure. By the time the engine reaches 3500 RPM, the actual maximum pressure rises to around 27.9 bar. This positive correlation between RPM and maximum pressure is consistent with typical engine behavior, where increased RPM results in higher combustion chamber pressures due to faster combustion cycles and greater heat generation.

The predicted maximum pressure closely mirrors the actual maximum pressure throughout the entire RPM range. At 1500 RPM, the predicted pressure is almost identical to the actual pressure, indicating the model’s high accuracy at lower RPMs. As RPM increases, the predicted maximum pressure remains closely aligned with the actual values, showing only minor deviations. For instance, at 2500 RPM, both the actual and predicted pressures are approximately 27.5 bar, demonstrating the model’s effectiveness in capturing the relationship between RPM and maximum pressure. Even at the upper end of the RPM spectrum, around 3500 RPM, the predicted pressure is very close to the actual pressure, slightly above 27.9 bar.

Overall, the model demonstrates excellent predictive performance for maximum pressure in the context of the E20 bio-fuel ratio. The close alignment of the predicted and actual pressure values across the entire range of RPMs suggests that the model is well-calibrated and capable of accurately predicting maximum pressure behavior in engines using this specific bio-fuel mixture. The minimal discrepancies observed indicate a reliable and robust model, providing valuable insights into engine performance and validating its use for predictive analyses in automotive engineering applications.

Figure 18 illustrates the relationship between engine RPM and Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) for a bio-fuel mixture of E20 (20% ethanol and 80% petrol). The plot compares actual BSFC values, represented by the blue line, with predicted BSFC values, indicated by the orange line, over an RPM range from 1500 to 3500.

At the lower end of the RPM spectrum, around 1500 RPM, the actual BSFC is relatively high, approximately 0.30 kg/kWh. This high BSFC at low RPM indicates less efficient fuel consumption, which is typical in engines operating at lower speeds. As RPM increases, BSFC begins to decline, reaching a minimum of around 0.22 kg/kWh at approximately 2500 RPM. This minimum indicates the RPM at which the engine operates most efficiently in terms of fuel consumption, achieving the lowest BSFC.

Beyond 2500 RPM, the actual BSFC starts to increase again, reaching approximately 0.25 kg/kWh at 3500 RPM. This increase suggests a decrease in fuel efficiency at higher RPMs, likely due to increased frictional losses and less optimal combustion conditions at higher speeds.

The predicted BSFC values closely follow the trend of the actual BSFC, albeit with slight deviations. At 1500 RPM, the predicted BSFC is slightly lower than the actual value, around 0.29 kg/kWh, indicating a small underestimation by the model. As RPM increases, the predicted BSFC decreases, mirroring the actual trend, and reaches a minimum of around 2500 RPM. However, the minimum predicted BSFC is slightly higher than the actual minimum, around 0.23 kg/kWh. This indicates that while the model accurately captures the trend of decreasing BSFC with increasing RPM, it slightly overestimates BSFC at the most efficient operating point. Beyond 2500 RPM, the predicted BSFC increases similarly to the actual BSFC, maintaining a close alignment up to 3500 RPM.

Overall, the model provides a reasonable approximation of the BSFC for the E20 bio-fuel ratio across varying RPMs, capturing the general trend of fuel consumption efficiency with RPM changes. The slight overestimation of BSFC at the most efficient RPM range suggests that while the model is robust, further refinement could enhance its accuracy, particularly in capturing the precise minimum BSFC values. Despite these minor discrepancies, the model’s predictions are sufficiently accurate for practical applications in assessing fuel efficiency in engines using ethanol–petrol blends.

Performance of E30 blend (30% Ethanol, 70% Gasoline)

Figure 19 demonstrates the relationship between engine RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) and combustion efficiency for both actual and predicted values using a biofuel blend of 30% ethanol and 70% petrol (E30). The analysis spans from 1750 to 3500 RPM, with combustion efficiency ranging from 69 to 75%. The data indicates a general negative correlation between RPM and combustion efficiency, as both actual and predicted values decrease with increasing engine speed.

At 1750 RPM, the actual combustion efficiency is observed to be around 74%, whereas the predicted value is slightly higher at approximately 75%. As RPM increases to 2500, the actual efficiency decreases to roughly 71%, while the model predicts an efficiency of about 72%, indicating a slight overestimation by the model. At 3500 RPM, the actual efficiency declines further to just below 70%, with the predicted value remaining slightly above 70%, continuing the trend of overestimation.

The model consistently overestimates combustion efficiency across the entire RPM range, with the most significant discrepancies occurring at lower RPMs. For example, at 1750 RPM, the model’s predictions are approximately 1% higher than the actual measurements. However, this discrepancy diminishes at higher RPMs, narrowing to less than 1% at 3500 RPM. This trend suggests that the model’s overestimation is more pronounced at lower engine speeds.

Notably, the actual combustion efficiency curve exhibits several fluctuations, particularly between 2500 and 3000 RPM, where efficiency briefly increases before continuing its decline. In contrast, the predicted values follow a smoother decline, missing some of these fluctuations. This suggests that while the model effectively captures the overall trend, it lacks the sensitivity to respond to the more subtle variations in combustion efficiency that occur at certain RPM ranges. The efficiency decline at higher RPMs (> 2500) occurs despite ethanol’s benefits due to (1) reduced residence time for complete combustion, (2) increased frictional losses dominating ethanol’s oxygen advantage, and (3) heat transfer losses exceeding gains from leaner mixtures17,19.

In summary, while the regression model provides a reasonable approximation of combustion efficiency for the E30 bio-fuel blend, it demonstrates a consistent bias toward overestimation. Furthermore, the model’s inability to capture certain fluctuations in the actual efficiency curve, particularly between 2500 and 3000 RPM, suggests that further refinement is necessary to enhance its accuracy and responsiveness across different engine speeds.

Figure 20 depicts the relationship between engine RPM and maximum pressure for both actual and predicted values using a 30% ethanol and 70% petrol (E30) biofuel blend. The analysis spans an RPM range of 1750 to 3250, with maximum pressure values ranging from 27.1 to 27.8 units. A strong positive correlation is observed, as both actual and predicted pressures increase with engine speed.

At 1750 RPM, the actual maximum pressure is approximately 27.1 units, while the predicted value slightly exceeds it at 27.15 units. As RPM increases to 2500, both actual and predicted pressures rise to about 27.4 units, with the model exhibiting a slight overestimation. At 3250 RPM, the actual pressure reaches approximately 27.75 units, closely aligning with the predicted value of 27.78 units.

Deviations between actual and predicted pressures remain minimal across the entire RPM range, with the most significant difference of 0.05 units occurring at 1750 RPM. This discrepancy decreases with increasing RPM, demonstrating the model’s ability to capture the relationship between engine speed and pressure with high accuracy.

Overall, the regression model exhibits strong predictive performance in estimating maximum pressure for the E30 biofuel blend. The close agreement between predicted and actual values, aside from minor overestimations at lower RPMs, highlights the model’s reliability in predicting pressure trends under varying engine speeds.

Figure 21 depicts the relationship between engine RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) and Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) for both actual and predicted values using a biofuel blend of 30% ethanol and 70% petrol (E30). The data reveals a U-shaped curve, where BSFC decreases as RPM increases to around 2500, before rising again at higher RPMs. At 1750 RPM, the actual BSFC is approximately 0.27 units, while the model predicts a slightly lower value of around 0.26 units. The minimum BSFC occurs near 2500 RPM, where the actual value reaches around 0.21 units, but the predicted value is higher at about 0.23 units, indicating an overestimation by the model. As RPM increases to 3250, the actual BSFC rises to about 0.26 units, with the predicted value closely aligning at around 0.25 units.

The model’s accuracy varies across the RPM range, with a tendency to underestimate BSFC at lower RPMs and overestimate it near the 2500 RPM region. The most significant deviation occurs at 2500 RPM, where the model overestimates BSFC by approximately 0.02 units compared to the actual value. This suggests that the model does not fully capture the peak efficiency at this RPM. However, at higher RPMs, the predicted values align more closely with the actual measurements, indicating improved model performance at these speeds.

Overall, while the regression model effectively captures the general trend of BSFC variation with RPM, some discrepancies are evident, particularly around the RPM range where BSFC is minimized. These results suggest that while the model performs well at predicting BSFC at higher engine speeds, further refinement is needed to enhance its accuracy at lower and mid-range RPMs for the E30 bio-fuel blend.

Comparison of experimental data with ANN predictions

Figure 22 presents a comparative analysis of actual and predicted combustion efficiencies for various bio-fuel ratios, ranging from 0 to 30% ethanol content, as a function of engine RPM. The solid lines represent the actual combustion efficiency, while the dashed lines indicate the predictions made by an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model. Different colors denote different bio-fuel ratios: yellow for 0% (Bio-Fuel 0), red for 10% (Bio-Fuel 10), blue for 20% (Bio-Fuel 20), and green for 30% (Bio-Fuel 30).

At 1500 RPM, the actual combustion efficiencies for the various bio-fuel ratios exhibit a range, with Bio-Fuel 30 showing the highest efficiency at approximately 77.5%, while Bio-Fuel 0 displays the lowest efficiency at around 65%. As the RPM increases, all bio-fuel ratios demonstrate a general decline in combustion efficiency, indicative of the typical relationship where higher engine speeds lead to reduced combustion efficiency due to increased thermal and frictional losses. By 3500 RPM, the actual combustion efficiency decreases to about 75% for Bio-Fuel 30 and drops to around 60% for Bio-Fuel 0.

The ANN model’s predictions, represented by dashed lines, show a similar downward trend across all bio-fuel ratios, indicating that the model captures the overall behavior of combustion efficiency with increasing RPM. However, there are noticeable discrepancies between the actual and predicted values. For instance, the model slightly underestimates the combustion efficiency for Bio-Fuel 30 across the entire RPM range, with a difference of about 1–2%. In contrast, for Bio-Fuel 0, the model overestimates the efficiency, particularly at lower RPMs, with deviations of up to 2.5%.

The combustion efficiency for intermediate bio-fuel ratios (Bio-Fuel 10 and Bio-Fuel 20) also follows this pattern. For Bio-Fuel 10, the actual efficiency starts at around 70% at 1500 RPM and decreases to approximately 65% at 3500 RPM. The ANN predictions closely track these values but generally show a slight overestimation. Similarly, for Bio-Fuel 20, starting from about 73% efficiency at 1500 RPM and decreasing to 68% at 3500 RPM, the predictions are close but tend to slightly underestimate the actual values.

Dhande et al.19 investigated the combustion efficiency of ethanol–gasoline blends and found that higher ethanol content (up to 30%) improved combustion efficiency due to better oxygen availability and leaner combustion, which aligns with the observed trends in this study. This supports the finding that Bio-Fuel 30 exhibits higher combustion efficiency compared to lower ethanol blends.

In summary, the ANN model demonstrates the capability to predict combustion efficiency trends across different bio-fuel ratios with reasonable accuracy. Although it consistently captures the overall decline in efficiency with increasing RPM, there are systematic biases in the predictions. These biases include underestimation for higher ethanol content fuels and overestimation for lower ethanol content fuels, suggesting that the model’s calibration could benefit from refinement to improve accuracy and minimize these prediction discrepancies. The model’s predictions provide valuable insights into the efficiency trends of bio-fuel blends, contributing to optimizing engine performance and fuel formulation strategies.

Figure 23 compares the experimental and predicted maximum pressure values as a function of engine RPM for different bio-fuel ratios, specifically 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% ethanol content. The actual data is depicted by solid lines, while the dashed lines represent predictions from an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model. The different colors indicate the various bio-fuel ratios: yellow for 0% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 0), red for 10% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 10), green for 20% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 20), and blue for 30% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 30).

At lower RPMs (around 1500 RPM), the actual maximum pressure values are fairly close for all bio-fuel ratios, ranging between approximately 26.8 bar and 27.0 bar. As the RPM increases, there is a noticeable increase in maximum pressure, which varies according to the bio-fuel ratio. For Bio-Fuel 0, the actual maximum pressure reaches about 28.2 bar at 3500 RPM. In contrast, Bio-Fuel 30, which has the highest ethanol content, shows a more moderate increase, reaching approximately 27.7 bar at the same RPM, indicating that higher ethanol content may lead to slightly lower maximum pressures at high RPMs.

The ANN model’s predictions closely follow the trends observed in the actual data. For Bio-Fuel 0, the predicted maximum pressure increases linearly, reaching approximately 28.4 bar at 3500 RPM, slightly overestimating the actual maximum pressure by about 0.2 bar. This overestimation trend is consistent across the other bio-fuel ratios as well. For instance, Bio-Fuel 10 reaches an actual maximum pressure of about 28.3 bar at 3500 RPM, while the model predicts around 28.5 bar. This overestimation of around 0.2 bar suggests a systematic bias in the ANN model’s predictions.

The model’s performance is more accurate for the higher ethanol content fuels. For Bio-Fuel 20 and Bio-Fuel 30, both the actual and predicted maximum pressures are closely aligned. For example, Bio-Fuel 20 shows a maximum pressure of about 28.0 bar at 3500 RPM, and the predicted value is nearly identical. Similarly, for Bio-Fuel 30, both the actual and predicted maximum pressures converge around 27.7 bar at 3500 RPM, indicating high predictive accuracy for fuels with higher ethanol content. Fayad et al. (2023)9 studied the effects of ethanol blends on BSFC and reported that ethanol blends (E10–E30) reduced BSFC at mid-RPM ranges due to improved combustion efficiency. However, at higher RPMs, BSFC increased due to higher frictional losses and incomplete combustion, which aligns with the observed trends in maximum pressure for higher ethanol blends.

And also, Ethanol has a high latent heat of vaporization (842 kJ/kg compared to gasoline’s 349 kJ/kg30), resulting in significant intake charge cooling. As ethanol vaporizes during the intake stroke, it absorbs more heat from the air–fuel mixture, thereby lowering the in-cylinder temperature. This cooling effect reduces peak combustion temperatures and, consequently, peak cylinder pressures. As shown in Fig. 23, E30 blends exhibit approximately 0.5 bar lower maximum pressure than E0 at 3500 RPM, primarily due to this thermal effect.

In summary, the ANN model effectively captures the trend of increasing maximum pressure with rising RPM for various bio-fuel ratios, demonstrating good predictive capability. Although the model tends to slightly overestimate maximum pressures, particularly for fuels with lower ethanol content, the predictions remain accurate within a margin of about 0.2 bar. This accuracy highlights the ANN model’s usefulness in simulating engine behavior under different fuel compositions, offering valuable insights into optimizing engine performance for various bio-fuel blends. Further refinement of the model could address the slight overestimations and improve predictive precision, especially for fuels with lower ethanol content.

Figure 24 provides a comparative analysis of actual and predicted brake-specific fuel Consumption (BSFC) across different bio-fuel ratios (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% ethanol content) as a function of engine RPM. The actual BSFC values are represented by solid lines, while the dashed lines indicate the predictions from an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model. The different colors represent different bio-fuel ratios: yellow for 0% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 0), red for 10% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 10), green for 20% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 20), and blue for 30% ethanol (Bio-Fuel 30).

At lower RPMs, around 1500 RPM, the actual BSFC values are higher for all bio-fuel ratios, indicating less efficient fuel consumption. For instance, Bio-Fuel 0 starts at a BSFC of approximately 0.31 kg/kWh, while Bio-Fuel 30 begins at a lower BSFC of around 0.26 kg/kWh. As the RPM increases, the BSFC values decrease, reaching a minimum at around 2500 RPM for all bio-fuel ratios. This trend is typical of internal combustion engines, where mid-range RPMs optimize fuel efficiency due to a balance between fuel–air mixture and engine load.

For Bio-Fuel 0, the minimum BSFC is observed to be approximately 0.27 kg/kWh at 2500 RPM, after which it increases again, reaching about 0.28 kg/kWh at 3500 RPM. Similarly, for Bio-Fuel 10, the BSFC reaches a minimum of about 0.26 kg/kWh and then rises slightly. Higher ethanol content fuels, such as Bio-Fuel 20 and Bio-Fuel 30, show lower BSFC values overall, indicating better fuel efficiency. Bio-Fuel 20, for instance, reaches a minimum BSFC of approximately 0.22 kg/kWh at around 2500 RPM, while Bio-Fuel 30 achieves a slightly lower minimum of about 0.21 kg/kWh.

The ANN model’s predictions, indicated by dashed lines, follow similar trends to the actual data, showing decreasing BSFC values up to the mid-RPM range and a subsequent increase at higher RPMs. However, the model tends to overestimate BSFC for Bio-Fuel 0, predicting a minimum of about 0.28 kg/kWh, which is higher than the actual minimum. This overestimation is consistent across other bio-fuel ratios as well, though the discrepancy decreases with increasing ethanol content. For example, the predicted minimum BSFC for Bio-Fuel 30 is about 0.22 kg/kWh, closely matching the actual value.

The ANN model’s performance improves for higher ethanol content fuels, with predictions for Bio-Fuel 20 and Bio-Fuel 30 closely aligning with the actual values. This suggests that the model is better calibrated for fuels with higher ethanol content, possibly due to more stable combustion characteristics and predictable fuel consumption patterns associated with ethanol. The slight overestimations in BSFC for lower ethanol content fuels highlight areas for model refinement to improve predictive accuracy. Kapusuz et al. (2015) and Thakur et al. (2022)17 found that ethanol blends increased peak cylinder pressure due to higher flame speeds and improved combustion characteristics, which supports the observed trends in BSFC for higher ethanol blends.

While the ANN model exhibits high predictive accuracy, minor deviations between actual and predicted values, particularly in BSFC and combustion efficiency, were observed. These discrepancies may be attributed to several factors: (1) environmental fluctuations such as ambient temperature and humidity, which affect combustion dynamics but were not explicitly modeled; (2) fuel property variability, where minor differences in ethanol purity or density between blends may have influenced results; and (3) unmodeled engine dynamics, including valve timing variations, heat losses, and turbulence effects at high RPMs. Incorporating these parameters in future modeling efforts or adjusting the ANN architecture to capture such nonlinearities could further improve accuracy.

In conclusion, the ANN model effectively captures the general trends in BSFC across different bio-fuel ratios and RPMs, demonstrating its utility in simulating fuel consumption for various engine operating conditions. While the model shows slight overestimations in BSFC, particularly for lower ethanol content fuels, it provides accurate predictions for higher ethanol content, highlighting the potential for optimizing engine performance through bio-fuel blends. Further model adjustments could reduce the discrepancies observed, enhancing the precision of BSFC predictions and supporting more efficient engine design and fuel management strategies.

In general, from a practical standpoint, deploying ANN models in engine control systems offers significant benefits. Once trained, these models require minimal computational resources and can be integrated into real-time control units for adaptive tuning and diagnostics. Compared to conventional calibration and testing methods, the ANN approach reduces time, cost, and fuel waste associated with trial-and-error testing. For instance, the cost of conducting extensive engine bench tests across multiple ethanol blends can be substantially reduced by replacing iterations with ANN-guided predictions. Although initial model development involves data acquisition and training, the long-term cost savings and performance gains make ANN integration a viable and cost-effective strategy for automotive manufacturers pursuing sustainable fuel alternatives.

Sample values of input and output data

Table 6 presents sample input and output data used for training the artificial neural network (ANN), providing insight into the model’s learning process. The input variables include key engine parameters, while the output represents the predicted performance metrics. These sample values illustrate the range and distribution of data used to optimize the ANN’s predictive capabilities. The inclusion of diverse training samples enhances the model’s ability to generalize across different operating conditions, ensuring robust and accurate predictions.

Conclusions

This study investigated the performance of a spark-ignition engine fueled with ethanol–petrol blends (E0, E10, E20, and E30) and utilized an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model to predict key engine performance parameters, including Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC), combustion efficiency, and maximum cylinder pressure. The combustion efficiency of ethanol–petrol blends was found to increase with higher ethanol content, with Bio-Fuel 30 (30% ethanol) exhibiting the highest efficiency of approximately 77.5% at 1500 RPM, compared to 65% for pure petrol (E0). This improvement is attributed to ethanol’s oxygenated nature, which promotes more complete combustion. However, combustion efficiency decreased with increasing RPM across all blends due to higher thermal and frictional losses at elevated engine speeds. The ANN model accurately captured this trend but showed slight overestimation for lower ethanol blends and underestimation for higher ethanol blends, indicating areas for further model refinement.

Ethanol blends demonstrated lower BSFC values compared to pure petrol, with Bio-Fuel 30 achieving the lowest BSFC of 0.21 kg/kWh at 2500 RPM, indicating improved fuel efficiency for higher ethanol blends, particularly in the mid-RPM range (2000–2500 RPM), where the engine operates at optimal conditions. At higher RPMs (above 2750 RPM), BSFC increased for all blends due to rising frictional losses and incomplete combustion. The ANN model effectively predicted BSFC trends but overestimated values for lower ethanol blends, suggesting the need for improved calibration to account for dynamic effects at high speeds. Maximum cylinder pressure increased with RPM for all fuel blends, with pure petrol (E0) reaching the highest pressure of 28.2 bar at 3500 RPM. Higher ethanol blends (E20 and E30) showed slightly lower maximum pressures, likely due to ethanol’s lower energy density and cooling effect during combustion. The ANN model accurately predicted maximum pressure trends but exhibited a slight overestimation (≈ 0.2 bar) for lower ethanol blends, particularly at higher RPMs, highlighting the model’s robustness but also underscoring the need for further refinement to enhance precision.

The ANN model demonstrated strong predictive capabilities for all performance parameters, with high correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.98) and low mean squared errors (MSE) for BSFC, combustion efficiency, and maximum pressure. The model’s accuracy improved for higher ethanol blends, likely due to the more stable combustion characteristics of ethanol. However, systematic biases, such as overestimation of BSFC for lower ethanol blends and underestimation of combustion efficiency for higher ethanol blends, were observed. These discrepancies suggest that the model could benefit from additional training data and refinement to better capture the complex interactions in engine dynamics. The study identified that the engine operates most efficiently at mid-RPM ranges (2000–2500 RPM), where BSFC is minimized, and combustion efficiency is maximized. This range represents the optimal operating condition for ethanol–petrol blends, balancing fuel–air mixture, combustion efficiency, and mechanical losses. Higher ethanol blends (E20 and E30) consistently outperformed pure petrol in terms of fuel efficiency and combustion efficiency, making them viable alternatives for reducing fossil fuel dependency and emissions.

The use of ethanol–petrol blends, particularly E20 and E30, can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve air quality due to ethanol’s oxygenated nature and cleaner combustion properties. The ANN model provides a cost-effective and time-efficient tool for optimizing engine performance and fuel blending strategies, reducing the need for extensive experimental testing. Further refinement of the ANN model is recommended to address the observed biases and improve accuracy, particularly for lower ethanol blends and high-RPM conditions. Additional studies could explore the effects of higher ethanol blends (E40, E50) and their impact on engine performance, emissions, and long-term engine durability. In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of ethanol–petrol blends to enhance engine performance and reduce emissions, supported by the robust predictive capabilities of the ANN model. The findings contribute to the development of sustainable energy solutions and provide valuable insights for optimizing engine design and fuel management strategies in the transition toward cleaner and more efficient transportation technologies.

While the ANN reduces experimental costs by 75%, its real-world deployment faces challenges: (1) sensor noise in field conditions may degrade accuracy, (2) long-term fuel blend stability is unmodeled, and (3) transient engine behaviors (e.g., sudden acceleration) require dynamic ANN training. Future work will integrate onboard diagnostics (OBD) data and hybrid ANN-physical models for robustness.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The experimental data supporting the findings, including engine performance parameters (combustion efficiency, BSFC, cylinder pressure) and ANN model configurations, can be provided for research validation purposes. However, some proprietary engine specifications may require permission from the Ethiopian Defence University before sharing. The ANN code framework is available in a public GitHub repository. Researchers interested in accessing the full dataset for replication or further analysis should contact the corresponding author with a detailed request outlining their intended use of the data.

Abbreviations

- BSFC:

-

Brake-specific fuel consumption (kg/kWh)

- E0:

-

Pure petrol (0% ethanol) (–)

- E10:

-

Ethanol–petrol blend (10% ethanol, 90% petrol) (–)

- E20:

-

Ethanol–petrol blend (20% ethanol, 80% petrol) (–)

- E30:

-

Ethanol–petrol blend (30% ethanol, 70% petrol) (–)

- LHV:

-

Lower heating value (MJ/kg)

- MSE:

-

Mean squared error (–)

- NOₓ:

-

Nitrogen oxides (–)

- Pmax:

-

Maximum cylinder pressure (bar)

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of determination (–)

- RPM:

-

Revolutions per minute (min⁻1)

- RMSE:

-

Root mean squared error (–)

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network (–)

- ASTM:

-

American society for testing and materials (–)

- CO: