Abstract

Mosquitoes are carriers of infectious diseases due to the presence of disease-transmitting vehicles such as parasites and vectors, causing severe health-related consequences to other millions of people yearly. The study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of utilizing Persea americana plant extracts in the management of mosquitoes and establishing eco-friendly methods of eradicating the vector. Methanol, ethanol, hexane, and acetone extracts of the leaves of Persea americana were prepared and examined for their insecticidal potency on the fourth instar larvae of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. All the extracts of the plants observed after 24 exposure hours showed significant larvicidal effects. More importantly, the LC50 of the ethanol, methanol and hexane extracts of P. americana were 14.606, 22.548 and 146.157 ppm, respectively. The combined synergistic insecticidal activity for the ethanol and methanol extract was found to be 15.181 ppm, while ethanol and hexane gave the LC50 of 22.548 ppm, and the ethanol and acetone extract had the LC50 of 54.606 ppm. Phytochemical screening confirmed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, and saponins in some of the extracts. GC-MS identified the plant contains fatty acids, heterocyclic compounds, and esters responsible for larvicidal action. The plant could be considered an economically and eco-friendly control in curbing the spread of some mosquito diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mosquitoes are part of the family Culicidae, and they comprise species with diverse behavioral features and ecological zones. Little insects have been living with mankind for a couple of millions of years with more than 3500 unique and identified species all over the globe. Included among these are the significant mosquito genera Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex. Each type of the mentioned species has certain characteristics, such as specific areas, feeding activities on humans, salient animals, and vectors of diseases. They are highly infectious agencies, particularly responsible for the transmission of different infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, Zika, and the West Nile virus, positioning themselves among the most dangerous creatures of mankind. Nevertheless, the tiny mosquitoes inflict major health, economic, and ecological impacts on people. Despite their small size, mosquitoes are deadly beasts that have the ability to infect humans with diseases, and in most cases they constitute an economic pest for human beings1,2. Mosquitoes are a group of insects that are characterized by slender and long legs with elongated mouth parts carrying the licking tube, the proboscis, that pierces the skin of the which facilitate the insect’s blood-feeding behavior. Male and female mosquitoes have to get nourishment from either nectars or ochre of plants; both, however, only female mosquitoes, after having had oestrous, require more feeding of blood3.

This aspect is related to the ability of mosquitoes to act as vectors. For example, if a mosquito drinks the blood of an infected animal, it transfers all biological materials taken with that blood—pathogens included. Further, these pathogens may be infected and injected into another human through the carrier of the dengue fever; the mosquito assumes that infection. For these geographical conditions, it was proper to perform many infectious diseases due to the presence of disease-transmitting vehicles such as carriers of parasites and pathogens4.

In ecology, mosquitoes have been involved in numerous activities. When the population of an organism increases dramatically in an ecosystem, in this case, the mosquito, the people or animals at the center of that ecosystem suffer negative effects. Moreover, their incidence may limit or interfere with some human activities, particularly in the areas where malaria occurs, resulting in losses on health care and reduced productivity5.

Interventions that are aimed at killing or reducing the population of mosquitoes and hence controlling the incidences of diseases associated with that have been in use for a number of years now. Measures include applying insecticides, adding or applying larvicides in various denying the mosquitoes breeding sites, and use of genetically modified mosquitoes purposely to lower their numbers or break the disease transmission cycle. However, there are other issues, such as insecticide resistance and new diseases that have appeared, that have made it difficult to control mosquitoes6.

The employment of vegetation in the management of mosquito larvae, referred to as larvicidal activity, is a method that has been in use in many societies over the years. Plants have different chemical substances that are larval control agents, meaning they are efficient in the place of synthetic pesticides. This method is also not only less detrimental to the ecology but also more practical and cheaper in many regions with few resources available7.

Many reports revealed the presence of contrasting studies in which plant extracts with aggressive properties to reduce the number of larvae of mosquitoes like the Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex species have been used8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Such extracts often comprise of active substances such as alkaloids, terpenes and terpenoids, flavonoids, and essential oil loads that adversely affect larval development, promote non-growth, or kill larvae. Interestingly, controlling the use of plant materials as larvicides reduces the likelihood of replacement of plant insecticides with chemical ones, as mosquitoes will not build resistance against them10.

Importantly, the use of larvicides made from plants is one of the options that can assist in the realization of successful and sustainable mosquito control methods commensurate with integrated vector management systems and environmentally benign pest management techniques: the use of plant-based larvicides8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Nonetheless, it would be beneficial to conduct further studies on how to improve the method of extraction, content of bioactive compounds, effectiveness, and cruelty evaluation of plant extract larvicides subjected to many environmental conditions15.

There has been growing interest in the study of Persea americana (avocado leaves) in the last few years, particularly because of some studies describing their medicinal activity. Investigation has shown the presence of active compounds such as flavonoids, phenols, and terpenoids, which allow the leaves to become therapeutic. It is also believed that it is the co-action of such compounds that is responsible for their effectiveness in producing health benefits16,17.

For example, the work of Ojewole16 showed that the avocado leaf extracts produced a more marked effect on blood pressure than any of its active constituents and went on to explain this observation by phytochemicals, quercetin malodour, and kaempferol in all providing an antihypertensive but not solely so. Also, the works of Rodriguez-Sanchez et al.17 included tests for the antimicrobial activity of avocado leaves, elucidating the presence of various active principles that could work together to eliminate various microbial infectious agents.

The favorable actions of avocado leaves towards different systems of the body are also useful in alleviating diabetes, heart diseases, and biofilm-associated infections. Additionally, their free radical scavenging and anti-penyakit terursol properties have been recognized for their likely potential in reducing oxidative stress and inflammation-based chronic disease, which is caused by several constant illnesses18.

There are several documented studies on the larvicidal properties exhibited by various plant species8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,19.

Relying solely on a single compound for insecticidal purposes can risk the development of resistance, similar to what is observed with chemical insecticides. Therefore, there is an increasing focus on creating mixtures of extracts to both amplify insecticidal effectiveness and minimize the likelihood of resistance in pest populations. Studies have shown that the active compounds in extract mixtures may interact in synergistic or antagonistic ways, influencing the overall activity of the extracts. This approach has been well-documented in prior research, underscoring the importance of leveraging these combinations for enhanced pest control strategies20,21,22.

Plant-based substances for controlling the mosquito population need to be employed, for which there is a need for a lot of regulatory approval and compliance to safety and environmental measures and laws, a factor that complicates and takes time to sort out. Furthermore, the synthesis, isolation, and preparation of the plant-derived larvicides may be expensive and therefore may not be cost-effective and readily available for use, especially in developing nations where mosquito-borne illnesses are common. The purpose of this research is to determine the effectiveness of utilizing plant-derived products in the management of mosquitoes via screening of plant extracts to determine which among them is most effective and their interaction in eliminating the mosquito vectors, with the general objective of establishing eco-friendly methods of eradicating the vector.

Hence, mosquitoes are more than merely nuisance insects; in fact, they are key players in the world’s health and environment. Knowledge of their biology, ethology, and pathogen epidemiology is essential to designing and implementing proper strategies for mosquito vector population control and consequently, the diseases these vectors transmit to humans and animals. Thus, the possibilities of using plants for enhancement of larvicidal efficacy present a viable direction in the fight against mosquito-borne diseases, as well as a potential to positively contribute to the protection of the environment and enhancement of the health and welfare of the community.

Materials and methods

Plant sample collection

The fresh leaves of a plant sample of Persea americana were collected, and the plant was identified by Mr. Alfred Ozioko, a taxonomist from the Bio-Resources Development and Conservation Programme (BDCP), Nsukka, Enugu State. The leaves of Persea americana were washed with a stream of water and air dried for two weeks at room temperature 25–27º C and room humidity 75–81%. The dried leaves were pulverized into a fine powder using an electric grinder and a sieve with a 0.4 mm mesh cloth. The resulting powder leaves were stored in an opaque container and preserved in a refrigerator at -4 degrees Celsius until further extraction processes were conducted23,24,25,26.

Preparation of phytochemical extract

The air-dried components of 100 g each of the leaf parts of Persea americana were precisely weighed and subjected to methanol, N-hexane, ethanol, and acetone extractions using a cold maceration method in the School of Preliminary Studies laboratory of the Federal College of Dental Technology and Therapy, Trans-Ekulu, Enugu State. The procedure involved two days of intense shaking. After that, the suspension was filtered using a Buchner funnel with ‘Whatman® No. 1’ filter paper measuring a size of 24 cm. The methanol crude extract obtained from the plant parts was then concentrated to dryness using a rotary vacuum evaporator with the model RE300 of ROTAFLO England at a temperature of 40 ± 5 °C. These crude methanol (CMPL), N-hexane (CHPL), ethanol (CEPL), and acetone (CAPL) extracts of Persea americana were held in a refrigerator at -4 °C until used27,28.

Test organism

The Ae. aegypti larvae were obtained from the National Arbovirus and Vectors Research Centre in Enugu. These larvae were kept and raised in tap water as well as housed in the School of Preliminary Studies, Federal College of Dental Technology and Therapy, Trans-Ekulu, Enugu State. To support the growth of the larvae, the following diets were offered to them: chicken feed (Grower) and fish in proportion of 3:1. The water in their rearing containers was replaced every other day until the larvae reached the fourth instar stage, at which point they were utilized for bioassays. The mosquitoes were reared under standard environmental conditions of temperature that ranged between 26 ± 03ºC, relative humidity of 80 ± 4%, and photoperiod regimes of 12 h light /12 hours dark29.

Mosquito larvicidal activity

Examined was the toxicity of different plant extract concentrations on Ae. aegypti larvae IV instar following the standard procedure29. The bioassays were carried out at a room temperature of 26 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 81 ± 2%. For the preparation of the stock solution of the extract, an emulsifier, which is Tween-80, was used so as to help dissolve the plant material in water. One gram of each of the plant extracts were weighed and mixed with 2 mL of Tween 80 to give the stock solution, which was then made up to 100 mL with tap water. Dilutions of the test solutions were made with appropriate diluents and serially diluted from 125 to 1000 ppm of each stock solution. For each replication, extract, and mosquito species, use 1 ml of the feed solution and 99 ml of tap water, respectively, as the negative control19.

Early IV instar larvae (25) were introduced into each 250-ml beaker containing 100 ml of the test solution, and larval mortality was recorded 24 h post-treatment. Four replicates were conducted simultaneously alongside the controls for each dose. Throughout the trials, the larvae received no nourishment. The number of dead larvae at each concentration was used to calculate the percentage mortality. The observed mortality was corrected using Abbott’s formula when the negative control mortality ranged from 5 to 20%. If bioassay tests showed > 20% negative control mortality or if larvae were unresponsive to gentle prodding with a fine needle, the experiments were discarded and repeated30.

Similar procedures were followed to assess the synergistic activities of four different solvents in the Persea americana extracts. Synergistic effects were determined against combinations of leaf parts of Persea americana. The combinations were prepared in the ratios of 50%:50% for Ethanol extract Persea leaf and Methanol Persea leaf extracts (CEPL&CMPL), Ethanol extract Persea leaf and Hexane Persea leaf extracts (CEPL&CHPL), and Ethanol extract Persea leaf and Acetone Persea leaf extracts (CEPL&CAPL). Using the method previously developed, the synergistic factor (SF) was determined. A value of greater than one suggests synergism, whereas a value of less than one shows antagonism31.

Phytochemical screening

Qualitative phytochemical screening to identify the components responsible for insect toxicity was conducted following the methods outlined by Ujam et al.32 and Onah et al.33. These methods are based on identifying the presence of specialized metabolites such as alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, phenolic compounds, steroids, terpenoids, oil, and lipids, which are recognized for having insecticidal qualities.

GC-MS analysis

The sample was analyzed using Agilent technologies 7890 A GC and 5977B MSD with experimental conditions of GC-MS system were as follows: Hp 5-MS capillary standard non-polar column, dimension: 30 M, 1D: 0.25 mm, film thickness: 0.25 μm. Flow rate of mobile phase (carrier gas: He) was set at 1.0 ml/min. In the gas chromatography part, temperature programme (oven temperature) was 40ºC raised to 250ºC at 5ºC/min and injection volume was 1 µl. Samples dissolved in methanol were run fully scan at a range of 40–650 m/z and the results were compared by using NIST Mass Spectral search programme.

Statistical analysis

When necessary, corrected mortality rates were calculated using Abbott’s formula. The percentage mortality data was subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 17.0)31. Means were separated using the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) test at a significance level of p < 0.05. Probit analysis was employed to determine the lethal concentrations (LC50 and LC90) that caused 50% and 90% mortality of larvae 24 h post-exposure. Additional statistical parameters calculated included slope, chi-square, and 95% confidence limits (upper and lower)12.

Results

\(\% \;{\text{yield}}={\text{weight}}\;{\text{ extract}}\;{\text{ divided }}\;{\text{by }}\;{\text{5}}0\;{\text{g}}\;{\text{ of }}\;{\text{plant }}\;{\text{material}}\;{\text{ multiplied }}\;{\text{by}}\;{\text{ 1}}00\)

The results of the percentage yield of the different leaf extracts of Persea americana are shown in Table 1. The result showed that the acetone had the highest percentage yield (2.6%), followed by ethanol (2.2%) and methanol (1.9%), while N-hexane extract had a yield of 0.6%.

Four solvent Persea americana leaf extracts with concentrations ranging from 125 to 1000 ppm were investigated for their larvacidal efficacy against Ae. aegypti. All four (4) extracts of Persea americana leaf had LC50 and LC90 values ranging between (14.606–441.181 ppm) and (46.517–1974.076 ppm), respectively, that caused potency against Ae. aegypti. Ethanol (CEPL) extract showed the highest potency, followed by methanol (CMPL), hexane (CHPL), and acetone (CAPL) in Table 2.

The synergistic of CEPL with other solvents of Persea americana leaf extracts with concentrations ranging from 125 to 1000 ppm had LC50 between 15.181 and 54.606 ppm after exposure to Aedes aegypti larvae for 24 h. It was discovered that CEPL and CMPL showed the highest toxicity in larvicidal activity at the lowest concentration of 125 ppm when compared with other synergy of solvent extracts (Table 3).

The phytochemical constituents of four solvent extractions of Persea americana leaf were found to be very strongly present, strongly present, moderately present, low present, and absent. The phytochemical investigation demonstrated the presence of alkaloids and saponins in CMPL and CAPL. However, these compounds were absent in CHPL and CEPL, despite the observed larvicidal activities of the latter. Three solvent extracts of Persea americana leaf, CMPL, CEPL, and CAPL, contained either flavonoids or resin flavonoids while found absent in CHPL (Table 4).

Discussion

Research into the potential application of phytochemically bioactive secondary metabolites for controlling mosquito vectors of vector-borne diseases has become increasingly essential. This urgency arises from the growing resistance of mosquitoes to synthetic insecticides, along with other challenges such as toxicity to humans and the need for environmentally friendly solutions.

The findings of this research showed that the acetone extract had the highest percentage yield among the tested solvents. These results align with the study conducted by Singh et al.34 on Andrographis paniculata leaf extracts, where the acetone extract demonstrated a yield of 22.5%, outperforming other solvents—ethanol (18.2%), methanol (15.6%), and hexane (10.3%). This similarity emphasizes the efficiency of acetone as an extracting solvent for bioactive compounds.

In this study, the larvicidal activities of methanol, N-hexane, ethanol, and acetone extracts of Persea americana leaf were evaluated against Aedes aegypti to determine which solvent caused the most physiological damage. The extracts demonstrated larvicidal potency at concentrations ranging from 125 to 1000 ppm, allowing for an assessment of potency as concentration increased. The observed larval mortality was attributed to the presence of secondary metabolites in the plant extracts, which are known for their larvicidal properties. Among the extracts, the ethanol leaf extract exhibited the highest larvicidal potency at concentrations of 125–1000 ppm, outperforming the methanol, N-hexane, and acetone extracts. Our findings align with those of Swathi et al.35who investigated the larvicidal and mosquito repellent properties of ethanolic extracts from Datura stramonium leaves. Their study reported LD50 values for larvicidal activity as 86.25 ppm for Aedes aegypti, 16.07 ppm for Anopheles stephensi, and 6.25 ppm for Culex quinquefasciatus. Additionally, Swathi et al. highlighted that the ethanolic extracts of Annona squamosa and Spondias mombin leaves demonstrated the highest efficacy in larvicidal and repellent activity against adult Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, emphasizing the potential of natural extracts in vector control8,35,36,37.

The findings of this study align with those of Yankanchi et al.38who observed that Lantana camara, Tridax procumbens, and Datura stramonium exhibited toxic effects on the larvae of Aedes aegypti. Additionally, combinations of these extracts, prepared at different concentrations, were found to be effective in controlling mosquito vector-transmitted diseases. Similarly, this study supports the research on Sterculia guttata seed extracts of hexane, ethanol, and chloroform, which demonstrated LC50 values of 35.52 ppm and 21.55 ppm against Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus larvae, respectively, within 24 h of treatment. These results highlight the promising potential of plant-based extracts in mosquito control efforts39.

Grace et al.40 documented the synergistic larvicidal effects of Citrus limon and Bacillus thuringiensis against the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Methanolic extracts of Citrus limon and Bacillus thuringiensis were tested on the 3rd instar larvae at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg/L. The LC50 values for Citrus limon were found to be 285.1 mg/L and 219.5 mg/L after 24 and 48 h, respectively. For Bacillus thuringiensis, the LC50 values were significantly lower at 1.9 mg/L and 1.4 mg/L after the same periods. When used together, the synergistic action resulted in enhanced larval mortality, with LC50 values of 158.5 mg/L and 109.9 mg/L after 24 and 48 h of exposure, respectively. This study highlights the potential benefits of combining these agents for effective vector control.

Matura et al.41 highlighted the larvicidal effects of a methanolic seed oil extract of Warburgia ugandensis against Aedes aegypti larvae at concentrations of 25, 50, 100, and 200 ppm. The seed oil was found to contain phytochemicals with significant larvicidal properties against Aedes aegypti. Similarly, Famuyiwa et al.42 investigated the larvicidal activity of various plant extracts and their fractions against Culex quinquefasciatus. The n-hexane fractions of Spondias mombin (0.81 ± 0.03 mg/mL) and Solanum macrocarpon (0.78 ± 0.03 mg/mL) exhibited the highest activity. A similar trend was observed with the leaf methanol extract and its n-hexane fraction, which demonstrated efficacy against both Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes aegypti. These findings emphasize the potential of plant-based extracts in mosquito vector control.

This study assessed the synergistic 24-hour bioassay effects of CEPL & CMPL, CEPL & CHPL, and CEPL & CAPL at concentrations of 125, 250, 500, and 1000 ppm on early IV instar Aedes aegypti larvae. Among these combinations, CEPL & CMPL exhibited the highest toxicity, with an LC50 value of 15.181 ppm. CEPL & CHPL followed with an LC50 value of 22.548 ppm, while the combination of CEPL & CAPL had the lowest toxicity, with an LC50 value of 54.606 ppm. The synergistic effects of the Persea americana leaf extract combinations demonstrated concentration-dependent mortality in A. aegypti larvae, supported by associated parameters such as slope ± SE and Chi-square values. This study aligns with prior research on the efficacy of pyriproxyfen and spinosad, both independently and in combination, against A. aegypti. Larval bioassays on susceptible mosquito larvae revealed mortality responses to these agents, individually and as a mixture. When combined in a 1500 rate admixture, pyriproxyfen and spinosad achieved LC50 and LC95 values of 0.019 (0.016–0.022) mg/L and 0.050 (0.040–0.065) mg/L, respectively. These findings highlight the enhanced larvicidal synergy achieved through synergistic combinations for A. aegypti mosquito control43.

Research has shown that combinations of plant extracts and microbial agents can significantly enhance larvicidal activity. For instance, studies involving mixtures of Aerval anata and Cynodon dactylon, as well as Boerhaavia diffusa and Commelina benghalensis, achieved 100% larval mortality. Similarly, a combination of Bacillus thuringiensis with chemical fungicides demonstrated a synergistic effect, reducing LC50 values by 30.68 for Aedes aegypti and 22.36 for Anopheles stephensi compared to individual fungicides40,44. Further supporting this, Darriet and Corbel43 highlighted the synergistic combination of pyriproxyfen and spinosad, which enhanced larvicidal efficacy against Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. These findings emphasize the potential of synergistic approaches for more effective mosquito vector control.

Phytochemical analysis of CMPL, CHPL, CEPL, and CAPL extracts from Persea americana demonstrated the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, and tannins. Notably, alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, and saponins were found in CMPL and CAPL extracts but were absent in CEPL. These bioactive metabolites are known for their larvicidal properties, primarily acting as mitochondrial toxins and inhibiting energy production44. The larvicidal efficacy observed in this study is likely due to the contribution of alkaloids and flavonoids, as these compounds have been previously documented for their bioactivity. Similarly, other secondary metabolites, such as saponins and tannins, are also known to enhance larvicidal activity, aligning with findings from earlier studies45,46. This is consistent with the work of Indabo and Zakari47who explored the larvicidal potency of methanolic leaf extract from Azadirachta indica against Dermestes maculatus. Their study identified a wide range of bioactive compounds, including alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, steroids, cardiac glycosides, glycosides, triterpenes, and carbohydrates. They reported a dose-dependent increase in larval mortality over 24, 48, 72, and 96 h at extract dosages of 0.20 g, 0.40 g, 0.60 g, and 0.80 g. Based on these findings, they advocated for the use of A. indica leaf extract in developing larvicides against D. maculatus.

Otabor et al.48 investigated the larvicidal efficacy of methanolic leaf extracts from Cymbopogon citratus, Ocimum gratissimum, and Vernonia amygdalina on third instar larvae of Culex quinquefasciatus. Their phytochemical analysis identified terpenoids, flavonoids, saponins, steroids, tannins, alkaloids, and glycosides in all three plant extracts. The findings demonstrated dose-dependent larvicidal activity, with O. gratissimum extract showing 18.33% and 43.3% mortality at 250 ppm and 1000 ppm, respectively, after 72 h. Additionally, Mamadou et al.49 examined the larvicidal potential of cyclohexane, chloroform, and methanol extracts from Cassia sieberiana leaves against Anopheles gambiae larvae. Four concentrations of each extract were tested over 48 h, revealing varying degrees of larval mortality. The chloroform extract exhibited the highest efficacy, achieving nearly 90% mortality after 48 h. Phytochemical screening indicated a wealth of secondary metabolites, including polyphenols and alkaloids, which are likely responsible for the observed larvicidal activity. These studies underscore the potential of plant-based extracts in vector control strategies.

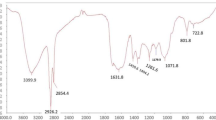

The spectra of the unknown compounds detected were compared to the known spectrum of compounds, which was stored in the database of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which has more than 70,000 patterns, and was employed for the GC-MS analysis. This present result showed the presence of twenty-nine compounds in the active extract (CEPL) of Persea americana that was subjected to GC-MS analysis. Twenty-nine bioactive compounds detected were: methyl valerate, 1,3-Propanediol, 2-ethyl-2-(hydroxymethyl)-, 5-Ethyl-1,3-dioxane-5-methanol, 2,4-Nonadienal, (E, E)-, 2-dodecenal, (E)-, octanoic acid, methyl ester, nonanoic acid, 9-oxo-, methyl ester, 2-n-octylfuran, tridecanoic acid, 12-methyl-, methyl ester, dodecanoic acid, methyl ester, 7-hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester, (Z)-, pentadecanoic acid, 14-methyl-, methyl ester, hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester, formamide, N-1-naphthalenyl-, pentadecanoic acid, 13-methyl-, methyl ester, Z,E-2,13-octadecadien-1-ol, 11-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, 1-azabicyclo(2.2.2)octane, 4-methyl-, 6-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, (Z)-, 9-octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester, cis-13-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, 9-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, (E)-, methyl stearate, hexadecanoic acid, 14-methyl-, methyl ester, oxiraneoctanoic acid, 3-octyl-, cis-, eicosanoic acid, methyl ester, 6-nitroundec-5-ene, bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid, methyl ester and docosanoic acid, methyl ester as shown in Table 5; Fig. 1.

Dey et al.50 identified several larvicidal compounds through GC-MS analysis, including tetradecanoic acid, cis-vaccenic acid, propanoic acid 2-oxo-methyl ester, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol, n-hexadecanoic acid, pentanal, and oleic acid. Similarly, Elumalai et al.51 conducted GC-MS analysis on Leucas aspera leaves, detecting compounds such as 1-hexadecanol, 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (zz)-methyl ester, 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester (zzz), heptadecanoic acid, 9-methyl-methyl ester, and eicosanoic acid, methyl ester, among others. Dakun et al.52 also analyzed methanolic extracts of Hyptis suaveolens, identifying twelve major compounds, including oleic acid (33.33%), octadecanoic acid (13.52%), and n-hexadecanoic acid (9.01%). In addition, Abutaha et al.53 and Priya and Jones54 identified twenty-nine bioactive components in their respective studies on Aloe ferox mill, Commiphora abyssinica, and P. longum, with common compounds such as hexadecanoic acid and its methyl ester being highlighted. A significant number of these phytochemicals, including monounsaturated fatty acids, cis-vaccenic acid, tetradecanoic acid, and hexadecanoic acid, are well-documented for their larvicidal, pesticidal, and nematicidal activities55. The GC-MS analysis of Persea americana revealed its phytochemical profile, which includes fatty acids, heterocyclic compounds, and esters, reinforcing its potential as a potent larvicide against Aedes aegypti. These findings further underline the plant’s bioactive capacity for effective vector control.

The study confirms that Persea americana extracts display remarkable larvicidal efficacy against Aedes aegypti mosquito larvae. Among the tested extracts, CEPL emerged as the most potent, as evidenced by its LC50 value and F-value. CMPL and CHPL demonstrated high toxicity, while CAPL showed moderate larvicidal activity. Notably, the combination of CEPL and CMPL had the strongest larvicidal effect, significantly increasing larval mortality. Most extracts, excluding CHPL, were rich in secondary metabolites like alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, and saponins, contributing to their larvicidal activity. GC-MS analysis identified the presence of fatty acids, heterocyclic compounds, and esters, which are key to the plant’s bioactivity. These findings underscore the potential of Persea americana extracts as eco-friendly and cost-effective agents for mosquito larvae control. Their application offers promising prospects for sustainable mosquito disease management.

Data availability

All datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article.

References

Harbach, R. E. The Culicidae (Diptera): A review of taxonomy, classification and phylogeny. Zootaxa 3609 (1), 1–80 (2013).

World Health Organization. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/aedes-aegypti-and-aedes-albopictus-mosquitoes (2016).

World Health Organization. Mosquito-borne diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mosquito-borne-diseases (2020).

Clements, A. N. The Biology of Mosquitoes: Development, Nutrition, and Reproduction, Vol. 1 (Springer, 1992).

Lounibos, L. P. Invasions by insect vectors of human disease. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 47 (1), 233–266 (2002).

World Mosquito Program. About Aedes mosquitoes. https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/en/our-work/mosquito-borne-diseases/aedes-mosquitoes (2021).

Pavela, R. Essential oils for the development of eco-friendly mosquito larvicides: a review. Ind. Crops Prod. 76, 174–187 (2015).

Eze, E. A., Pierre, S., Danga, Y. & Okoye, F. B. C. Larvicidal activity of the leaf extracts of Spondias mombin linn. (Anacardiaceae) from various solvents against malarial, dengue and filarial vector mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Vector Borne Dis. 51, 300–306 (2014).

Lame, Y., Nukenin, N. E., Danga, Y. S. P., Ajaegbu, E. E. & Esimone, C. O. Laboratory evaluations of the fractions efficacy of Annona senegalensis (Annonaceae) leaf extract on immature stage development of malarial and filarial mosquito vectors. J. Arthropod-Borne Dis. 9, 2:226–237 (2015).

Govindarajan, M. & Benelli, G. Facile biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Barleria cristata: mosquitocidal potential and biotoxicity on three non-target aquatic organisms. Parasitol. Res. 115 (2), 925–935 (2016).

Danga, S. P. Y., Aboubakar, O. B. F., Ndouwe, H. M. T., Yonki, B. & Ngadvou, D. Towards the use of extracts from Plectranthus glandulosus (Lamiaceae) and Callistemon rigidus (Myrtaceae) leaves to indoor-spray (control) malaria and other arboviral diseases vector mosquitoes. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 8 (5), 2049–2054 (2020). Lame Y, Ajaegbu EE, Esimone CO, Nukenine EN.

Onah, G. T. et al. Larvicidal and synergistic potentials of some plant extracts against Aedes aegypti. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 10 (2), 177–180 (2022).

Ibe, I. C., Ajaegbu, E. E., Younoussa, L., Danga, S. P. Y. & Ezugwu, C. O. Larvicidal Property of the Extract and Fractions of Hannoa klaineana against the Larvae of Aedes aegypti. Current. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 39 (17), 127–132 (2020).

Nwaso, B. C. et al. Larvicidal efficacy of Hyptis pectinate leaf extracts against Aedes aegypti 4th instar larvae in Nigeria. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. (JESP). 54 (3), 491–498 (2024).

Priyanka, P. & Senthilkumar, N. Larvicidal activity of selected plant extracts against Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry. 7 (2), 2168–2171 (2018).

Ojewole, J. A. Hypoglycemic and hypotensive effects of Persea americana mill (Lauraceae) leaf aqueous extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 115 (3), 387–392 (2008).

Rodriguez-Sanchez, D. G. Antibacterial activity of leaf extracts of Mexican avocado (Persea Americana Mill.) against Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. Pharmacognosy Res. 7 (Suppl 1), S12–S18 (2015).

Abd Elkader, A. M. et al. Phytogenic compounds from avocado (Persea Americana L.) extracts; antioxidant activity, amylase inhibitory activity, therapeutic potential of type 2 diabetes. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29 (3), 1428–1433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.11.031 (2021).

Ajaegbu, E. E., Onah, G. T., Ikuesan, A. J. & Bello, A. M. Larvicidal potency of some selected Nigerian plants against Aedes aegypti. Chem. Proc. 14 (1), 35 (2023).

Hummelbrunner, L. A. & Ismam, M. B. Acute, sub-lethal, antifeedant, and synergistic effects of monoterpenoid essential oil compounds on the tobacco cutworm, Spodoptera litura (Lep. Noctuidae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 715–720 (2001).

Pavela, R., Vrchotova, N. & Triska, J. Mosquitocidal Activities of Thyme Oils (Thymus Vulgaris L.) against Culex quinquefasciatus (Culicidae, 2009). Parasitology research 105.

Sarma, R., Adhikari, K., Mahanta, S. & Khanikor, B. Combinations of plant essential oil based terpene compounds as larvicidal and adulticidal agent against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci. Rep. 9, 9471 (2019).

Ikuesan, A. J., Ajaegbu, E. E., Ezeh, C. U., Dieke, A. J. & Onuora, A. L. HPLC analysis and antimicrobial screening of methanol extract/fractions of the root of Millettia aboensis (Hook.f.) Baker against Streptococcus mutans. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 39 (22), 1–11 (2020).

Ajaegbu, E. E. et al. Antimicrobial Evaluation of the Extract/Fractions of the Millettia aboensis (Leguminosae) Stem against Streptococcus mutans. European J. Med. Plants. 31 (13), 1–11 (2020).

Ezeh, C. U. et al. Secondary metabolites from the leaf of Milletia aboensis against Streptococcus Mutans isolated from carious lesions. Int. J. Cur Res. Rev. 12 (19), 172–177 (2020).

Ezeagha, C. C. et al. Molucidine and desmethylmolucidine as immunostimulatory lead compounds of Morinda Lucida (Rubiaceae). Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 5 (5), 977–982 (2021).

Ajaegbu, E. E., Eboka, C. J., Okoye, F. B. C. & Proksch, P. Cytotoxic effect and antioxidant activity of pterocarpans from Millettia aboensis root. Nat. Prod. Res. 18, 1–6 (2023).

Ajaegbu, E. E., Danga, S. P. Y., Ikemefuna, U., Chijoke, I. U. & Okoye, F. B. C. Mosquito adulticidal activity of the leaf extracts of Spondias mombin L. against Aedes aegypti L. and isolation of active principles. J. Vector Borne Dis. 53, 17–22 (2016).

Ajaegbu, E. E. et al. Mosquitoes’ larvicidal activity of Phoenix dactylifera Linn extracts against Aedes aegypti. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 10, 4:54–58 (2022).

Ajaegbu, E. E., Onah, G. T., Ikuesan, A. J. & Bello, A. M. Larvicidal synergistic efficacy of plant parts of Lantana camara against Aedes aegypti. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 10 (1), 187–192 (2022).

Ujam, N. T. et al. The phyto-chemical screening, antibacterial and antipyretic properties of extracts of Chrysophyllum albidum leaves. Inter J. Res. Innovat Appl. Sci. (IJRIAS). 9 (3), 461–472 (2024).

Onah, G. T., Ajaegbu, E. E. & Enweani, I. B. Proximate, phytochemical and micronutrient compositions of Dialium guineense and Napoleona imperialis plant parts. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 18 (03), 193–205 (2022).

Singh, R., Singh, P., Kumar, M. & Kumar, V. Comparative study of the extraction yields of Andrographis paniculata leaf extracts using different solvents. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry. 7 (3), 248–253 (2018).

Swathi, S., Murugananthan, G., Ghosh, S. K. & Pradeep, A. S. Larvicidal and repellent activities of ethanolic extract of Datura stramonium leaves against mosquitoes. Int. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemical Res. 4 (1), 25–27 (2012).

Ajaegbu, E. E., Younoussa, L., Danga, S. P. Y., Uzochukwu, I. C. & Okoye, F. B. C. Mosquito-repellant activity of Spondias mombin L (family: Anacadaceae) crude methanol extract and fractions against Aedes aegypti L. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 7 (3), 240–244 (2016).

Okoye, T. C. et al. Antimicrobial effects of a lipophilic fraction and Kaurenoic acid isolated from the root bark extracts of Annona senegalensis. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2012, 831327. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/831327 (2012).

Yankanchi, S. R., Yadav, O. V. & Jadhav, G. S. Synergistic and individual efficacy of certain plant extracts against dengue vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J. Biopest. 7 (1), 22–28 (2014).

Katade, S. R., Pawar, P. V., Wakharkar, R. D. & Deshpande, N. R. Sterculia guttata seeds extractives- an effective mosquito larvicide. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 44, 662–665 (2006).

Grace, M., Subramanian, A. & Samuel, T. Synergistic larvicidal action of Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck (Rutaceae) and Bacillus thuringiensis Berliner 1915 (Bacillaceae) against the dengue vector Aedes aegypti Linnaeus 1762 (Diptera: Culicidae). GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 10 (01), 25–33 (2020).

Matura, J. A. N., Walekhwa, M. N. & Otieno, F. O. Larvicidal activity of the methanolic extract of warburgia ugandensis seed oil on Aedes aegypti. J. Sci. Innov. Creat. (2022).

Famuyiwa, F. G., Adewoyin, F. B., Oladiran, O. J. & Obagbemi, O. R. Larvicidal activity of some plants extracts and their partitioned fractions against Culex quinquefasciatus. Int. J. Trop. Disease Health. 41 (11), 23–34 (2020).

Darriet, F. & Corbel, V. Laboratory evaluation of Pyriproxyfen and spinosad, alone and in combination, against Aedes aegypti larvae. J. Med. Entomol. 43 (6), 1190–1194 (2006).

Rajasekaran, A. & Duraikannan, G. Larvicidal activity of plant extracts on Aedes aegypti L. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2 (S3), S1578–S1582.

Wiseman, Z. & Chapagain, B. P. Larvicidal effects of aqueous extracts of Balanties aegyptiaca (desert date) against the larvae of Culex pipens mosquitoes. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 4 (11), 1351–1354 (2005).

Khana, V. G. & Kannabiran, K. Larvicidal effect of Hemidesmus indicus, Gymnema sylvestre and Eclipta prostrate against Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larvae. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 3, 307–311 (2007).

Indabo, S. S. & Zakari, R. Phytochemical screening and larvicidal effect evaluation of Azadirachta indica (l) leaf extract on Dermestes maculatus (De geer, 1774) infestation of smoked clarias gariepinus (burchell, 1822). FUDMA J. Sci. (FJS). 4 (2), 41–45 (2020).

Otabor, J. I., Rotimi, J., Opoggen, L., Egbon, I. N. & Uyi, O. O. Phytochemical constituents and larvicidal efficacy of methanolic extracts of Cymbopogon citratus, Ocimum gratissimum and Vernonia amygdalina against Culex quinquefasciatus larvae. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage 23(4), 701–709 (2019).

Mamadou, K. et al. Phytochemical screening and evaluation of the larvicidal activities of three organic extracts derived from the leaves of Cassia sieberiana to control Anopheles gambiae, the vector of malaria. Chem. Sci. Int. J. 33 (1), 47–53 (2024).

Dey, P., Mandal, S., Goyary, D. & Verma, A. Larvicidal property and active compound profiling of Annona squamosa leaf extracts against two species of diptera, Aedes aegypti and Anopheles stephensi. J. Vector Borne Dis. 60, 401–413 (2023).

Elumalai, D., Hemalatha, P. & Kaleena, P. K. Larvicidal activity and GC–MS analysis of Leucas aspera against Aedes aegypti, Anopheles stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Saudi Soc. Agricultural Sci. 16, 306–313 (2017).

Dakum, Y. D. et al. Larvicidal efficacy and GC-MS analysis of Hyptis suaveolens leaf extracts against. Anopheles Species. 30 (1), 8–19 (2021).

Abutaha, N., Al-mekhlafi, F. A., Wadaan, M. A. & Al-Khalifa, M. S. Larvicidal activity and chemical compositions of Aloe ferox mill, and Commipora abyssinica (O.Berg) combination against the mosquito vectors larvicidal Culex pipiens L. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 34, 101962 (2022).

Priya, N. R. P. & Jones, R. D. S. Larvicidal activity and GC-MS analysis of Piper longum L. leaf extract fraction against human vector mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Int. J. Mosq. Res. 8 (4), 31–37 (2021).

Tewari, H., Jyothi, K. N., Kasana, V. K., Prasad, A. R. & Prasuna, A. L. Insect attractant and oviposition enhancing activity of hexadecenoic acid ester derivatives for monitoring and trapping Caryedon serratus. J. Stored Prod. Res. 61, 32–38 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E.A. and G.T.O.; Investigation: E.E.A., and A.M.B.; methodology, E.E.A., G.T.O., A.J.I., A.M.B.; formal analysis, E.E.A., G.T.O., A.J.I., A.M.B.; resources, E.E.A. and G.T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.I.; writing—review and editing, E.E.A., G.T.O., A.J.I., A.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ajaegbu, E.E., Onah, G.T., Ikuesan, A.J. et al. Synergistic potency and GC-MS analysis of Persea americana extracts against Aedes aegypti. Sci Rep 15, 33902 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08105-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08105-z