Abstract

A Pi-Sigma neural network (PSNN) is a kind of neural network architecture that blends the structure of conventional neural networks with the ideas of polynomial approximation. Training a PSNN requires modifying the weights and coefficients of the polynomial functions to reduce the error between the expected and actual outputs. It is a generalization of the conventional feedforward neural network and is especially helpful for function approximation applications. Eliminating superfluous connections from enormous networks is a well-liked and practical method of figuring out the right size for a neural network. We have acknowledged the benefit of L2/3 regularization for sparse modeling. However, an oscillation phenomenon could result from L2/3 regularization’s nonsmoothness. This study suggests a smoothing L2/3 regularization method for a PSNN in order to make the models more sparse and help them learn more quickly. The new smoothing L2/3 regularizer eliminates the oscillation. Additionally, it enables us to show the PSNN’s weak and strong convergence findings. In order to guarantee convergence, we also link the learning rate parameter and the penalty parameter. Results of the simulation are provided. We present the simulation results, which demonstrate that the smoothing L2/3 regularization performs significantly better than the original L2/3 regularization, thereby supporting the theoretical conclusions are offered as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pi-sigma neural networks (PSNNs)1,2,3,4,5,6, a category of higher-order neural networks, demonstrate superior mapping capabilities compared to conventional feedforward neural networks. These networks have shown efficacy in multiple applications, including nonlinear satellite channel equalization, seafloor sediment classification, and image coding. In3, introduced the PSNN. It computes the product of the sums originating from the input layer, as opposed to the sums of the products. Hold the weights connecting the product layers and the summation layers constant at a value of 1. The gradient descent algorithm, in the context of data samples, is a fundamental and extensively utilized method for training neural networks. It includes both the batch gradient algorithm and the online gradient algorithm. The network processes all training samples before the weight updates in the batch gradient algorithm7. Upon processing each training sample, the online gradient algorithm updates the weights8. This research utilizes the batch gradient algorithm. Enhancing a network’s generalization performance is essential for achieving effective model performance on previously unexplored data. There are Researchers may utilize various techniques to accomplish this objective. Researchers improved the capabilities of PSNN, leading to its broader application in these domains. Most researchers have carefully looked into how common these networks are, focusing on their ability to do parallel computing, have non-linear mapping functions, and be adaptable. They can mitigate the limitations of conventional neural networks, such as slow learning rates and insufficient generalization performance. Furthermore, they can serve as a component in higher-order neural networks, such as Pi-sigma-pi. Thus, the examination of PSNN optimization and its theoretical analysis is crucial9,10.

Overfitting is a common problem in both machine learning and statistical modeling. It happens when a model adapts too much to the training data, picking up noise and fluctuations instead of the main pattern. This leads to a model that exhibits strong performance on the training dataset while demonstrating inadequate performance on the test dataset. Researchers have proposed various regularization approaches to address overfitting in neural networks. This category encompasses \({L}_{2}\) regularization11, \({L}_{1}\) regularization12, and elastic net regularization13. Dropout is an additional method for regularizing neural networks14. This research utilizes a neural network penalty term to facilitate pruning. The principle involves incorporating a regularizer into the standard error function, as outlined below:

where \(\widetilde{E}\left(w\right)\) is the standard error depending on the weights \(w\), \({\Vert w\Vert }_{\text{p}}={\left(\sum_{k=1}^{n}{\left|{w}_{i}\right|}^{p}\right)}^{1/p}\) is the \({L}_{p}\)-norm, and \(\lambda >0\) is regularization parameter. The \({L}_{0}\) regularizer is the variable selection regularization method that has been solved the fewest times. This is because it is an NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem15. In references16,17,18, researchers present a smoothing \({L}_{0}\) regularizer. In19, researchers discuss the popular \({L}_{1}\) regularizer. References20,21,22 present a smoothing \({L}_{1}\) regularizer. In23, the authors present the \({L}_{1/2}\) regularizer and show that it is more sparse than the \({L}_{1}\) regularizer, among other beneficial features. In references24,25,26, the authors present a smoothing \({L}_{1/2}\) regularizer. In this paper, we will use the \({L}_{2/3}\) regularizer for network regularization.

Finding a weight vector \({w}^{*}\) such that \(E\left({w}^{*}\right)=\text{min}E(w\)) is the aim of network learning. The associated weight vectors for each iteration by

where \(\eta\) is the learning rate. The authors of27 examined the usefulness of \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization for deconvolution in imaging processes. This study demonstrated that applying the restricted isometry condition and the \({L}_{2/3}\) technique for \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization can achieve sequential convergence. A number of tests demonstrate that using closed-form thresholding formulas for \({L}_{P}\) (\(P=1/2, 2/3\)) regularization improves the performance of \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization for image deconvolution when compared to \({L}_{0}\)28,29 \({L}_{1/2}\), and \({L}_{1}\)30. In some situations, the \({L}_{2/3}\) algorithm converges to a local minimizer of \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization, and its rate of convergence grows linearly asymptotically. In31, this is demonstrated. Many other algorithmic applications can theoretically use the obtained results. Additionally, the study in32 showed how the \({L}_{2/3}\) strategy subsequently converged with regard to \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization. The study also established an error limit for the limit point of any convergent subsequence, which was determined by the constrained isometry condition.

This article adds the \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term to the batch gradient method for PSNN computation. The conventional \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term is not smooth at the origin, according to our research. Our numerical studies show that this feature leads to oscillations in numerical calculations and presents challenges for convergence analysis. The \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization concentrates extensively on image processing, demonstrating its efficiency and quality through experiments that yielded remarkable results. This regularization lacks effective methods for processing neural networks, which are responsible for regulating weight adjustments to minimize error rates. Consequently, we aim to elucidate this organization and showcase its efficacy in managing neural networks from both theoretical and practical perspectives. We propose a modified \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term that smoothes the traditional term at the origin in order to get around this restriction. Four numerical examples demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed strategy.

This paper is organized as follows. “Numerical results” section delineates PSNN and the batch gradient method with smoothing \({L}_{2/3}\) regularizer. “Classification problems” section supporting simulation results. A concise conclusion is presented in “Conclusion” section. Finally, we have relegated the proof of theorem to the Appendix.

Materials and methods

In computational mathematics and applied mathematics, optimization theory and methods are rapidly gaining popularity due to their numerous applications in various fields. Through the use of scientific methods and instruments, the “best” solution to a practical problem can be identified among a variety of schemes. This is the subject’s involvement in the optimal solution of mathematically defined problems. In this process, optimality requirements of the problems are studied, model problems are constructed, algorithmic techniques of solution are determined, convergence theory of the algorithms is established, and numerical experiments with typical and real-world situations are conducted. The reference [33] provides a detailed discussion of this subject.

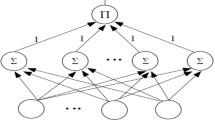

Pi-sigma neural network

This section describes the batch gradient approach, which uses smoothing \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization, as well as the network structure of PSNN. The input layer, summation layer, and product layer dimensions of PSNN are \(p, n,\) and 1, respectively. An activation function, \(f:R\to R\), is presented. For every result in this study, the logistic function \((x)=1/(1 +\text{exp}(-x))\) is chosen for a nonlinear activation function \(f(x)\) and an input data vector \(x\in {R}^{p}\). If you need a binary result, you can utilize the thresholding or signum procedures. Connections made by adding units to an output will always have a weight of 1. This means the network isn’t taking advantage of the concept of hidden units, which would otherwise allow for very quick calculations. In a j-th summing unit, \({w}_{j}\) the stands for the weight vector that links the input layer to that unit.

and write

Then, the output of the network is calculated by

where \({w}_{j}\cdot x\) is the usual inner products of \({w}_{j}\) and \(x\).

The originally \({{\varvec{L}}}_{2/3}\) regularization method (O \({{\varvec{L}}}_{2/3}\))

Suppose that we are supplied with a set of training samples \({\left\{{O}^{l},{y}^{l}\right\}}_{l=1}^{L}\subset {R}^{p}\times R\), where \({O}^{l}\) is the desired ideal output for the input \(x\). By adding an \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term into the the usual error function, the final error function takes the form

The partial derivative of the above error function with respect to \({w}_{ji}\) is

where \(\lambda >0\) is the regularization parameter, \({\widehat{E}}_{{w}_{ji}}\left(w\right)=\partial \widehat{E}\left(w\right)/\partial {w}_{j}\), and \({\delta }_{l}^{\prime}\left(t\right)=-\left({O}^{l}-f\left(t\right)\right)f^{\prime}(t)\). The batch gradient method with originally \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term (O \({L}_{2/3}\)) systematically increases the weights \({w}^{m}\) from an unlimited initial amount \({w}^{O}\) by

where \(i=\text{1,2},\cdots ,p;j=\text{1,2},\cdots n;m=\text{0,1},\cdots\), and \(\eta >0\) is the learning rate.

The smoothing \({{\varvec{L}}}_{2/3}\) regularization method (S \({{\varvec{L}}}_{2/3}\))

The literature’s earlier work on non-convex regularization, specifically \({L}_{1/2}\) regularization, motivates this method to produce a better approximation. Nevertheless, it generates an optimization problem that is neither Lipschitz nor convex or smooth. This complicates the convergence analysis and, more significantly, results in oscillations in the numerical computation, as observed in numerical experiments. In order to get over this limitation, the author used a smoothing function to approximate the goal function, which is usually Eq. (8) (see25). Similar to \({L}_{1/2}\) regularization, the standard \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization also lacks differentiation at the origin. We employ the same method mentioned in reference Eq. (8), which is known as the following formula, to eliminate any conundrum from our newly suggested algorithm:

where \(\varepsilon\) is a small positive constant. Then, we have

It is easy to get

Let \(G\left(z\right)\equiv {\left(g\left(z\right)\right)}^{2/3}\). Note that

and that

Now, the new error function with smoothing \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term is

The derivative of the error function \(E\left(w\right)\) in Eq. (9) with respect to \({w}_{ji}\) is

The new batch gradient method with smoothing \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term (S \({L}_{2/3}\)) systematically increases the weights \({w}^{m}\) from an unlimited initial amount \({w}^{O}\) by

where \(i=\text{1,2},\cdots ,p;j=\text{1,2},\cdots n;m=\text{0,1},\cdots\), and \(\eta >0\) is the learning rate.

Numerical results

Function approximation is one of the many areas in which PSNNs may be used; they work especially well in jobs where polynomial functions can be used to approximate the relationship between inputs and outputs. We examine the numerical simulations of the examples to demonstrate the effectiveness of our suggested learning approach. We compared our smoothing \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization approach (SL2/3) with smoothing \({L}_{1/2}\), originally \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization (OL2/3), and originally \({L}_{1/2}\) regularization (OL1/2).

Example 1

In this example, we study the sin function to compare the approximation performance of the above algorithms.

The algorithm selects 101 training samples using an evenly spread interval from \(-4\) to \(+4\). We choose to use 70% of the 101 input training samples for training purposes and 30% for testing purposes. One output node, two input nodes, and four summation nodes make up the neural network. We adjusted the learning rate and the regularization parameter to approximately 0.05 and 0.003, respectively. We choose the starting weights at random from the range \([-0.5, +0.5]\). Ten thousand is the maximum number of iterations.

See the error function’s performance curve for SL2/3, OL2/3, OL1/2, and SL1/2 in Fig. 1. When compared to the other approaches, SL2/3 clearly provides the best approximation performance. Figure 1 displays an improved approximation for the SL2/3 valid function. Table 1 display the average training error (AvTrEr), and running duration of ten experiments. Furthermore, Table 1 displays the the average numbers of neurons eliminated (AvNuNeEl) and the time required by four pruning algorithms across 10 trials. Initial findings demonstrate that SL2/3 outperforms competitors in terms of speedup and generalization, which is highly encouraging.

Example 2

A nonlinear function Eq. (14) has been devised to compare the approximation capabilities of the SL2/3 OL2/3, O \({L}_{1/2}\) and SL1/3.

The technique uses a uniformly distributed interval between − 4 and + 4 to choose 101 training samples. Of the 101 input training samples, we decide to employ 70% for training and 30% for testing. The neural network is composed of four summation nodes, two input nodes, and one output node. We changed the regularization value to about 0.001 and the learning rate to about 0.05. The initial weights are randomly selected from the interval [− 0.5, + 0.5]. The maximum number of iterations is 10,000.

Figure 2 shows the performance curve of the error function for SL2/3, OL2/3, OL1/2, and SL1/2. It is evident that SL2/3 offers the best approximation performance when contrasted with the other methods. An enhanced approximation for the SL2/3 valid function is shown in Fig. 2. Ten experiments’ running times and average training error (AvTrEr) are shown in Table 2. Additionally, Table 2 shows the time needed by four pruning algorithms across ten trials as well as the average number of neurons removed (AvNuNeEl). It is quite encouraging to see that preliminary results show that SL2/3 performs better than competitors in terms of speedup and generalization.

Example 3

Examining how batch gradient algorithms that incorporate four penalty terms perform is the primary goal of this test. By applying penalties using the 2D Gabor function (see Eq. (15)), we demonstrate that the PSNN can approximate functions effectively. The 2D Gabor function takes the following form:

An evenly distributed 6 × 6 grid on \(-0.5\le x\le 0.5\) and \(-0.5\le y\le 0.5\) is used to pick 36 input training samples. Also, the input test samples consist of 256 points chosen at random from a 16 × 16 grid with a range of \(-0.5\le x\le 0.5\) and \(-0.5\le y\le 0.5\). There are 2 input nodes, 5 nodes for summation, and 1 node for output in the neural network. Around 0.6 was the learning rate, and about 0.002 was the regularization parameter that we set. We choose the starting weights at random from the range \([-0.5, +0.5]\). Ten thousand is the maximum number of iterations.

Figure 3 display the four methods’ typical network approximations. Our method SL2/3 provides the best error performance approximation. Each of the four learning algorithms (SL2/3, OL2/3, OL1/2 and SL1/2) had its AvTrEr, and AvNuNeEl given in Table 3. Our SL2/3 approach once again demonstrates superior accuracy and a superior sparsity-promoting characteristic.

Example 4

Because the machine learning algorithm must discover a complicated pattern in the data, the parity problem is difficult. The problem is challenging due to a number of features, such as symmetry, non-linearity, and high dimensionality. The well-known XOR problem can be thought of as a particular instance of the two-dimensional parity problem. The 5-bit parity problem is used in this example. Five input nodes, six summation nodes, and one output node make up the network, which has a regularization parameter of \(\lambda =0.001\) and a learning rate of \(\eta =0.03\). Figure 4 shows the average performance of each of the four algorithms with a maximum number of iterations of 4000. We choose the initial weights at random from the interval \([-0.5, 0.5]\). Table 4 shows the input samples of the 5-dimensional parity problems (Table 5).

Figure 4 shows that SL1/2 error function decreases more monotonically than that of OL2/3, OL1/2, and SL1/2. As expected by Theorem A.1, Fig. 4 illustrates how the error functions become closer to very small positive constants. Additionally, the oscillation is eliminated by the SL2/3. The error of SL2/3 is less than that of OL2/3, OL1/2, and S \({L}_{1/2}\) when the training settings are the same. The outcomes of the 10 trials for each learning algorithm are displayed in Tab. 5 for anerge error AvErTr, norm of gradient (AvNoDr), and AvNuNeEl.

Classification problems

In order to verify the performance of the new algorithm proposed in this paper, we compared it with the other three learning algorithms. The classification data sets are selected from the UCI database (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/) and listed in Table 6, which including thirteen binary classification problems. The specification of the network structure and learning parameters for classification problem datasets are listed in Table 6. Each data set is randomly divided into two subsets with a fixed percentage, training, and testing samples are separately set to be 2/3 and 1/3.

To analyze the effectiveness of the experiments, Table 7 lists two performance metrics, namely training accuracy and testing accuracy to show the classification capability of the network. From Table 7, the testing accuracy and training accuracy of the S\({L}_{2/3}\) algorithm is higher than the O\({L}_{2},\) O\({L}_{1}\), O\({L}_{2/3}\), O\({L}_{1/2}\), and S\({L}_{1/2}\) algorithms, it can be concluded that the proposed new algorithm performs well, with better generalization. And in terms of training time, it can be found that the proposed new algorithm takes less time.

Conclusion

In this paper, a new batch gradient method for SPNN with smoothing \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization. This work presents an approach for learning a modified smoothed \({L}_{2/3}\) regularization term. We have identified the strategy to mitigate oscillation and demonstrated its convergence. This technique streamlines the computation of the gradient error function and enhances learning efficiency compared to current results. Consequently, this method produces a more efficient pruning outcome. Furthermore, our study bases its convergence outcomes on a novel premise. Moreover, the theoretical results and advantages of this algorithm are also illustrated by four numerical examples.

Data availability

The datasets and code used during the current study are available from the corresponding author and also professor Yan Xiong (Email: xy-zhxw@163.com) on reasonable request, and the UCI Machine Learning Repository datasets are available in (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/).

References

Hussain, A. J. & Liatsis, P. Recurrent pi-sigma networks for DPCM image coding. Neurocomputing 55(1–2), 363–382 (2003).

Jiang, L. J., Xu, F. & Piao, S. R. Application of pi-sigma neural network to real-time classification of seafloor sediments. Appl. Acoust. 24, 346–350 (2005).

Shin, Y. & Ghosh, J. The pi-sigma network: An efficient higher-order neural network for pattern classification and function approximation. In IJCNN-91-Seattle international joint conference on neural networks Vol. 1, 13–18. (IEEE, 1991).

Shin, Y., Ghosh, J. & Samani, D. Computationally efficient invariant pattern recognition with higher order Pi-Sigma Networks. The University of Texas at Austin. (1992).

Akram, U., Ghazali, R. & Mushtaq, M. F. A comprehensive survey on Pi-Sigma neural network for time series prediction. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. (JTEC) 9(3–3), 57–62 (2017).

Husaini, N. A. et al. Pi-Sigma neural network for a one-step-ahead temperature forecasting. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Appl. 13(04), 1450023 (2014).

Liu, Y., Yang, D., Nan, N., Guo, L. & Zhang, J. Strong convergence analysis of batch gradient-based learning algorithm for training pi-sigma network based on TSK fuzzy models. Neural Process. Lett. 43, 745–758 (2016).

Mohamed, K. S. et al. Convergence of online gradient method for pi-sigma neural networks with inner-penalty terms. Am. J. Neural Netw. Appl. 2(1), 1–5 (2016).

Kang, Q., Fan, Q. & Zurada, J. M. Deterministic convergence analysis via smoothing group Lasso regularization and adaptive momentum for Sigma-Pi-Sigma neural network. Inf. Sci. 553, 66–82 (2021).

Fan, Q., Kang, Q., Zurada, J. M. & Life Fellow, I. E. E. E. Convergence analysis for sigma-pi-sigma neural network based on some relaxed conditions. Inf. Sci. 585, 70–88 (2022).

Groetsch, C. The Theory of Tikhonov Regularization for Fredholm Equations 104 (Boston Pitman Publication, 1984).

Ranstam, J. & Cook, J. A. LASSO regression. J. Br. Surg. 105(10), 1348–1348 (2018).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat Methodol. 67(2), 301–320 (2005).

Zhang, Z. & Xu, Z. Q. J. Implicit regularization of dropout. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 46, 4206 (2024).

Wang, C., Venkatesh, S. & Judd, J. Optimal stopping and effective machine complexity in learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 6. (1993).

Nguyen, T. T., Thang, V. D., Nguyen, V. T. & Nguyen, P. T. SGD method for entropy error function with smoothing l 0 regularization for neural networks. Appl. Intell. 54, 1–16 (2024).

Zhang, H. & Tang, Y. Online gradient method with smoothing ℓ0 regularization for feedforward neural networks. Neurocomputing 224, 1–8 (2017).

Fan, Q. & Liu, T. Smoothing l0 regularization for extreme learning machine. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020(1), 9175106 (2020).

Mc Loone, S. & Irwin, G. Improving neural network training solutions using regularisation. Neurocomputing 37(1–4), 71–90 (2001).

Mohamed, K. S. Batch gradient learning algorithm with smoothing L 1 regularization for feedforward neural networks. Computers 12(1), 4 (2022).

Mohamed, K. S. & Albadrani, R. M. Convergence of batch gradient training-based smoothing L1regularization via adaptive momentum for feedforward neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Technol. Eng. Explor. 11(116), 1005 (2024).

Huang, Y. M., Qu, G. F. & Wei, Z. H. A new image restoration method by Gaussian smoothing with L 1 norm regularization. In 2012 5th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing 343–346 (IEEE, 2012).

Xu, Z., Zhang, H., Wang, Y., Chang, X. & Liang, Y. L 1/2 regularization. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 53, 1159–1169 (2010).

Yu, D., Kang, Q., Jin, J., Wang, Z. & Li, X. Smoothing group L1/2 regularized discriminative broad learning system for classification and regression. Pattern Recogn. 141, 109656 (2023).

Wu, W. et al. Batch gradient method with smoothing L1/2 regularization for training of feedforward neural networks. Neural Netw. 50, 72–78 (2014).

Li, W. & Chu, M. A pruning feedforward small-world neural network by dynamic sparse regularization with smoothing l1/2 norm for nonlinear system modeling. Appl. Soft Comput. 136, 110133 (2023).

Gao, W., Sun, J. & Xu, Z. Fast image deconvolution using closed-form thresholding formulas of lq (q= 12, 23) regularization. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 24(1), 31–41 (2013).

Blumensath, T., Yaghoobi, M., & Davies, M. E. Iterative hard thresholding and l0 regularisation. In 2007 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing-ICASSP’07 Vol. 3 III-877 (IEEE, 2017).

Xu, Z., Chang, X., Xu, F. & Zhang, H. $ L_ 1/2 $ regularization: A thresholding representation theory and a fast solver. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 23(7), 1013–1027 (2012).

Daubechies, I., Defrise, M. & De Mol, C. An iterative thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems with a sparsity constraint. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. J. Issued Courant Inst. Math. Sci. 57(11), 1413–1457 (2004).

Zhang, Y. & Ye, W. L2/3 regularization: Convergence of iterative thresholding algorithm. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 33, 350–357 (2015).

Liu, L. & Chen, D. R. Convergence of ℓ2/3 regularization for sparse signal recovery. Asia-Pacific J. Oper. Res. 32(04), 1550023 (2015).

Yuan, Y. & Sun, W. Optimization Theory and Methods (Springer, 1997).

Acknowledgements

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Khidir Shaib Mohamed: Conceptualization, writing original draft and editing, analysis and interpretation of results, review and supervision. Raed Muhammad Albadrani: Writing original draft and editing, Writing – review and editing. Ekram Adam: Writing – review and editing, Writing – review and editing, review and verify results. Yan Xiong: Writing–dataset and review the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, K.S., Albadrani, R.M., Adam, E. et al. Batch gradient based smoothing L2/3 regularization for training pi-sigma higher-order networks. Sci Rep 15, 24424 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08324-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08324-4