Abstract

There has been a dramatic increase in flood events over Greater Jakarta since 2019. However, little study has been found regarding physical characteristics of rainfall during flood events. This study investigates the rainfall drop size distribution during the three cases of severe flood events in the Jakarta area on 31 December 2019–1 January 2020 (Case 1), 15–16 July 2022 (Case 2), and 6–12 October 2022 (Case 3). The characteristic of rainfall drop size is analysed and categorised based on stratiform, convective, and mixed convective-stratiform rainfall. This research used the Automatic Weather Station, Laser Precipitation Monitor, and ERA5 reanalysis datasets from December 2019 to October 2022. Overall, results show that raindrops with particle diameters up to 4 mm exist during the three flood cases over the lowland and mountainous regions. The mountainous region has a higher number of larger diameter sizes compared to the lowland. In Cases 1 and 2, the occurrence of stratiform rainfall dominated the lowland areas, while the convective rainfall was also present in the mountain during Case 1. In contrast to Cases 1 and 2, over the lowland during Case 3, mixed stratiform and convective rainfall have a significant proportion. Meanwhile, the stratiform and convective rainfall over the mountainous region occurred equally. The most prominent feature in Case 1, the stratiform rainfall persisted from 14 to 13 LT on the following day, coinciding with the severe flood over the Jakarta region. The anomaly of high moisture convergence and substantial negative vertical velocity over the lowland during Case 1 might generate a long duration stratiform rainfall that likely contributed significantly to floods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an archipelagic country located between two oceans and two continents, the complex atmospheric system over Indonesia influences global weather and climate patterns1,2. These intricate weather patterns often lead to hydrometeorological disasters. As the capital city of Indonesia, the Jakarta region is one of the most prone cities to climate-related hazards, such as flooding3. The database from the Indonesian National Agency for Disaster Management during 2020–2022 recorded at least 277 flood events in Jakarta and its surrounding areas4. Numerous research studies have been conducted to analyse various drivers associated with meteorological and climatological factors inducing Jakarta floods. Studies about floods related to extreme rainfall show that floods were not only caused by large-scale circulations such as El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO)5,6,7, Cross Equatorial Northerly Surge (CENS)8,9, and equatorial waves10 but also by local factors such as land–sea breeze circulation and the complex local topography11. Moreover, the interconnection between these phenomena is known to be responsible for the development of the mesoscale convective system. Analysing the rainfall characteristics, such as rainfall drop size distribution during the flood event, is a crucial part of understanding the mechanism behind rainfall events.

Drop size distribution (DSD) is one of the fundamental microphysical properties of rainfall formation and play an essential role in improving short-term prediction of extreme rainfall events and estimation. Several instruments are used to measure DSD including disdrometers, ground-based weather radar, and space-borne weather radar. Despite the advancements of the DSD observation technology, disdrometer is acknowledged as the instrument that can provides the highest accuracy of the DSD data12.

Based on prior studies, DSD characteristics showed significant differences between convective and stratiform rainfall13. In situ DSD measurements indicate that larger drops are mostly generated by convective rainfall. In contrast, stratiform rainfall produces smaller drops13. The large raindrops in convective rainfall are caused by the dominant coalescence, rimming, and aggregation processes of the small drops. Meanwhile, the smaller raindrops in stratiform rainfall are formed by deposition from vapor onto ice particles14,15. The updraft velocity in the convective clouds plays a vital role in the drop growth process enabling the drops to transform into a larger size before falling as precipitation16. Regional variability of DSD shows the terrain effect on the DSD characteristics17. The raindrops tend to be smaller in convective and stratiform rainfall due to the orographic force that triggers collision and coalescence processes18.

There has been various research in understanding the variability of DSD over regions in Indonesia, such as Java, Sumatera, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua Islands12,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. These studies analysed the ground-based DSD measurements, the DSD’s vertical profile, and the diurnal and seasonal variations. One key finding from these studies is that the vertical gradient of the DSD in convective rainfall is larger than in stratiform rainfall, indicating that a stronger updraft in convective clouds can modify the drops through drop sorting and enhancement of the collision-coalescence process12. Although extensive research has been conducted to examine DSD characteristics in Indonesia in recent years, the number of studies specifically focusing on variations of DSD over Jakarta and its surrounding areas is scarce, particularly on the analysis of the DSD during heavy rainfall possibly leading to floods. Meanwhile, understanding detailed rainfall types (such as convective and stratiform rainfall) and investigating which dominant rainfall types induce extreme rainfall are imperative to better mitigate floods and associated risks. A better understanding of precipitation and microphysical processes and structures are crucial factors for improving weather prediction and precipitation estimation. Currently, simulation and prediction of weather and climate in Indonesia have not been very accurate due to the complexity of the climate and weather system and a lack of understanding of the main processes driving the system.

Despite some research related to floods existed in Jakarta, there was a limited investigation about the microphysical properties and the microstructure of the extreme rainfall. In this study, we will use rainfall DSD data from the disdrometer in Serpong (lowland) and Bogor (mountain) to examine microphysical features of rainfall during three different flood events in the Jakarta area. The flood events were selected based on the highest casualties in Jakarta and the surrounding area during 2020–2022. The first case happened during the wet season (December–February/DJF) in January 2020, the second flood took place during the transitional phase (September–October/SON) in October 2022, and the third one occurred during the dry season (June–August/JJA) in July 2022.

Data and methods

Jakarta and its surrounding regions have a monsoonal rainfall pattern characterised by distinct wet and dry seasons29,30. This pattern significantly influences extreme rainfall events that might lead to severe flooding. However, significant flood events can still occur outside the usual wet season due to unusual atmospheric conditions. Three different study cases were selected from major flood events in and around Jakarta, which include Case 1 (31 December 2019–1 January 2020), Case 2 (15–16 July 2022), and Case 3 (6–12 October 2022). Based on the floods database during 2020–2022 obtained from the Indonesian National Agency for Disaster Management portal, during the first case, the heavy rainfall commenced on 31 December 2019. The severe flooding began in the early morning of 1 January 2020, inundating large parts of the Greater Jakarta Area including Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi. The floodwaters persisted in some areas until 4 Jan 2020, causing widespread disruption and damage with casualties of 51 fatalities, 7410 damaged houses, 109,121 inundated houses, and 115 damaged public infrastructures4. The second case is considered a rare event as it occurred during the dry season. Despite this, the flooding affected substantial areas, including parts of North, South, East, and West Jakarta, as well as Bogor and South Tangerang on 15 July 2022. The following day, the inundated area covers Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi, affecting a total of 4969 flooded residences. The third case, which happened during the transitional season, involved multiple flooding events. The 6 and 7 October 2022 floods covered the southern part of Greater Jakarta, including South Jakarta, South Tangerang, Bogor, and the southern part of Bekasi. Additional flooding on 9 and 12 October primarily impacted Bogor. These third flood events resulted in ten fatalities, six injuries, 11 damaged houses, 3310 inundated homes, and one damaged public infrastructure. These three selected cases represent a general seasonal pattern during the wet, dry, and transitional seasons over Indonesia, particularly over Jakarta and surrounding regions.

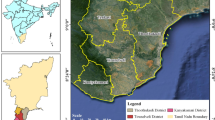

This study used a laser precipitation monitor sensor, Thies Clima Laser Precipitation Monitor (LPM), to observe surface rainfall and its characteristics based on the Drop Size Distribution (DSD) information. The two sites of LPM observations are selected to represent the lowland region at Serpong (106.67° E, 6.36° S) and the mountainous regions at Bogor (106.80° E, 6.60° S). Figure 1a presents the study area covering Greater Jakarta in the coastal region in the northwestern part of Java Island, the lowland, and the mountainous regions in the southern part of Jakarta. The altitude of the region is ranging up to 2 km. Rainfall observations using LPM in Serpong have been conducted continuously since 2017, whereas observations in Bogor commenced in 2019 and are limited to the rainy season, with no data recorded between March and November. Therefore, during case 2 (15–16 July 2022) in Bogor, no analysis was conducted. The time unit used in this study is Local Time (LT = UTC + 7h), which represents West Indonesian Standard Time (WIB).

Greater Jakarta is situated in the coastal region in the northwestern part of Java Island, as well as the lowland and mountainous regions in the southern part of Jakarta (a) with LPM disdrometer locations ( ). The spatial distribution of total rainfall amount during each rain event from Automatic Weather Stations (¡) around Jakarta for Case 1: 31 December 2019–1 January 2020 (b), Case 2: 15–16 July 2022 (c), and Case 3: 6–12 October 2022 (d). Map generated in this figure was plotted using opensource software named Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) v632, the topography data was derived from NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Global 3arc second33.

). The spatial distribution of total rainfall amount during each rain event from Automatic Weather Stations (¡) around Jakarta for Case 1: 31 December 2019–1 January 2020 (b), Case 2: 15–16 July 2022 (c), and Case 3: 6–12 October 2022 (d). Map generated in this figure was plotted using opensource software named Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) v632, the topography data was derived from NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Global 3arc second33.

In general, the LPM records raindrop size and rainfall speed data with a 1-minute resolution. This laser-based instrument uses a laser-optical beaming source to produce a parallel light beam (infrared, 785 nm, not visible) with a horizontal sample area of (228 × 20) mm2. A photodiode with a lens is situated on the receiver side to measure the optical intensity by transforming it into an electrical signal. The analysis includes the events that occur in the wet (Case 1), dry (Case 2), and transitional to wet (Case 3) seasons over the lowland and mountainous regions. However, due to the missing data, no analysis was conducted for Case 2 in the mountain area.

The Automatic Weather Stations (AWS) and C-band weather radar data belong to the Indonesia Agency for Meteorological, Climatological, and Geophysics (BMKG). ERA5 reanalysis31 is secondary data used in this study. Figure 1b, c, and d show spatial distributions of rainfall amount from the Automatic Weather Stations (AWS) around Jakarta for Cases 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The spatial distribution of rainfall in Fig. 1b indicates extreme rainfall exceeding 350 mm, while Fig. 1c shows consistent high rainfall across all AWS data in Greater Jakarta, ranging between 50 and 100 mm. The relatively uniform rainfall distribution in Fig. 1c shows that the flood event impacted almost the entire Greater Jakarta area, as nearly all AWS stations recorded similar rainfall amounts. Fig. 1d highlights the highest recorded rainfall in the affected areas in the southern part of the Greater Jakarta area, with the most intense rainfall in the range of 350–400 mm spotted in the Bogor area.

LPM data processing

The LPM measures the number of raindrops at each diameter (i) and velocity (j) bin. Each sample of data consists of 22 diameter sizes and 20 speed class bins, respectively, with different bin widths. Due to the inherent limitation of LPM measurement, quality control has been applied prior to the data analysis, such as (1) selecting data with rainfall intensity greater than 0.1 mm, (2) eliminating data that falls outside the range of 60% of the empirical equation34, (3) removing the first two bins (0–0.125 mm and 0.125–0.25 mm) due to the low signal-to-noise ratio, and (4) excluding samples with 1-min total counts of raindrop less than 10.

To differentiate between two rainfall categories (convective and stratiform), methods from previous studies were used35,36. The classification uses the LPM rainfall intensity data; if the rainfall rates of 10 consecutive 1-min samples are ≥ 5 mm h−1 and the standard deviation is > 1.5 mm h−1, the rainfall is considered convective rainfall, and if the rainfall rates are ≥ 0.5 mm h−1 but less than 1.5 mm h−1 and the standard deviation is ≤ 1.5 mm h−1, is categorised as stratiform rainfall. Cases that do not meet these criteria are classified as mixed convective–stratiform rainfall.

After separating the rainfall based on stratiform and convective categories, the droplet concentrations are next calculated to explore the DSD and other physical characteristic conditions that occurred at each LPM observation location. The raindrop concentration for the i-th diameter bin per unit volume (m−3 mm−1) is expressed as follows:

where \({D}_{i}\) is the mean diameter class i, Δnij is the drop number at i-th size and j-th speed, Δt is the sampling time, which was every 60 s, v(Di) is the fall velocity in the i-th size bin (mm s−1), Ai (m−2) is the effective sampling area, which can be estimated by Eq. (2):

where \(l\) and \(w\) are the length and width of the infrared beam area, respectively.

The integral parameters of rainfall rate R (mm h−1), radar reflectivity factor Z (mm6 m−3), liquid water content W (g cm−3), mass-weighted mean diameter Dm (mm), and normalised intercept parameter Nw (mm−1 cm−3) are calculated using equations (3) to (7):

where ρw is the water density (1.0 g cm−3).

Characterisation of DSD can be expressed by the Gamma distribution37, with three parameters: No, µ, Λ, which are intercept parameter (mm−1−µ m−3), shape parameter, and slope parameter (mm−1), respectively, expressed in equation (8):

These three parameters can be calculated using the moment fitting method.

Reanalysis data

The ERA5 hourly data on single levels and pressure levels with 0.25° × 0.25° spatial resolution and hourly temporal resolution are used for this study. There are five variables selected to support the analysis for this study, i.e., MVIMD (Mean Vertically Integrated Moisture Divergence), CAPE (Convective Available Potential Energy), vertical velocity (w), also \(u\) and \(v\) component at 850 mb.

MVIMD is the rate of moisture flow transported horizontally, and the unit is expressed in kg m−2 s−1. Positive values of MVIMD indicate moisture divergence, where moisture is dispersed, while negative values indicate moisture convergence, where moisture is concentrated in specific areas. Moisture convergence has been known to be associated with heavy precipitation38. The ERA5 data will be used to understand general background conditions during the flood events. Since ERA5 provides a coarser resolution both spatially (≈27 km × 27 km) and temporally (hourly data), a single grid point may not align well with the LPM’s exact location, thus failing to capture the localised precipitation. The areal average is calculated for the Bogor area (106.73° E–106.84° E, 6.68° S–6.50° S) and the Serpong area (106.65° E–106.75° E, 6.41° S–6.25° S). This approach aims to minimise error between the two locations by smoothing out small-scale variations and providing a better representation of the broader atmospheric conditions. For the analysis purpose, the hourly anomaly is calculated by subtracting the hourly data from the respective month’s long-term hourly average.

Results

Physical properties of rainfall

Figure 2 presents the type, droplet size, and number of rainfalls in the Serpong (lowland) and Bogor (mountainous) regions during three different flood events on 31 December 2019–1 January 2020 (Case 1), 15–16 July 2022 (Case 2), and 6–12 October 2022 (Case 3). The results show that many raindrops (n > 100) with particle sizes up to 4 mm in diameter exist during three flood cases in the two regions. The distinct part is that the mountainous area has a considerably high number of larger sizes of diameter (approximately up to 4 mm) compared to the lowland (up to 3 mm).

Raindrop number and rainfall classification (coloured marks in the upper panel) from LPM observation for Case 1 in Serpong (a) and Bogor (b); Case 2 in Serpong (c); Case 3 for 6–7 October 2022 in Serpong (d) and Bogor (e); and Case 3 for 11–12 October 2022 in Bogor (f). There was no data for Case 2 (15–16 July 2022) in Bogor and no rainfall for Case 3 (11–12 October 2022) in Serpong.

In Case 1, Greater Jakarta experienced a severe flood coincident with a high rainfall amount of up to 377 mm (Fig. 1b). During this precipitation event, the LPM captures a long-duration rainfall period from 15 LT on 31 December 2019 to 15 LT on 1 January 2020 over the lowland (Fig. 2a). In contrast to the lowland, precipitation initiates earlier in the mountainous region, starting at 12 LT and continuing until 13 LT the following day, with no and less rainfall observed between 21–02 LT and 13–01 LT (Fig. 2b). The most distinct part is that a larger drop number with a small diameter (≤ 2 mm) prevails more over the lowland relative to the mountain. Over the mountainous region, a large drop number with a high diameter (≥ 3 mm) is predominant. It is suggested that stratiform rainfall is the main responsible driver in generating small rainfall intensity over the lowland, as shown in Fig. 2a. In contrast, the convective rainfall that develops over the mountain has resulted in large rainfall intensity. The relative contribution of stratiform rainfall has reached around 58% (Table 1) during Case 1 of all samples measured in the LPM. This indicates that the occurrence of stratiform rainfall is more dominant than the occurrence of convective rainfall in Case 1.

In case 2, which represents the flood event during the dry season, the long-duration rainfall occurred between 18 LT on 15 July 2022 and 13 LT on 16 July 2022 over the lowland area (Fig. 2c), mostly generated from the stratiform cloud. However, a small fraction of convective rainfall may produce a significant number of raindrops with a diameter greater than 2 mm, particularly in the evening (18–20 LT) on 15 July 2022. Figure 3b also supports this analysis, as the black line (lowland) shows reflectivity of 30–40 dBZ during 16–21 LT, highlighting a convective system that later transitioned to a lower echo of 20–30 dBZ and persisted until 13 LT the next day, indicating long-lasting stratiform rain. In Case 2, the occurrence of stratiform rainfall has a major contribution to the total rainfall types in the lowland, contributing approximately 51% (Table 1).

The rainfall characteristics in Case 3 notably differ from those in Case 1, particularly over the lowland. In Case 3, a short duration of rainfall with a drop size greater than 2 mm occurs on 6–7 October 2022 and begins earlier than in Case 1, specifically during 13–19 LT on 6 October 2022 and 15–19 LT on the following day over the lowland (Fig. 2d). Meanwhile in the mountain, rainfall starts later than in the lowland (Fig. 2e). Moreover, rainfall with a high number of drops (n > 100) and a large diameter (up to 4 mm) is found over the mountain in the afternoon (16 LT) on 11 October 2022 and 15–19 LT on 12 October 2022 (Fig. 2f), while no rainfall is recorded over the lowland during this period (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). Like Case 1, the larger raindrops originated from the convective rainfall.

In the wet season (Case 1), stratiform and convective rainfall appear simultaneously with the peak timing of the flood which aligns with the convective rainfall that occurred from afternoon (16 LT) on 31 December 2019 to morning (07 LT) on the following day over the lowland. Meanwhile, stratiform rainfall has a longer duration than convective rainfall, which appears from the afternoon (16 LT) to the afternoon of the following day (13 LT) (Fig. 2a). The result is quite similar to a previous study39 due to the same sequential variation that mentioned the convective rainfall occurs at 16 LT and is transitioned to stratiform in the evening (19 LT) during January through February 2010 (wet season). The time-latitude cross-section along 106.5° E–107.0° E of C-band radar composite reflectivity (Fig. 3a) further confirms the similarity, showing the large extent of the area of echoes that appeared in the afternoon (16 LT)40. Cases 2 and 3 also tend to have similar features, even though the stratiform and convective rainfall occur later in Case 2 and earlier in Case 3. For example, in Case 3, in the lowland area the convective rainfall appears in the afternoon at around 13 LT; afterwards, it was dominated by the stratiform rainfall at 15 LT onwards and finally diminishes in the early morning (Fig. 2d). Radar reflectivity in Fig. 3c further supports this finding, with reflectivity reaching 30–40 dBZ at 13 LT before transitioning to widespread stratiform precipitation, indicated by lower echoes of 20–30 dBZ. This precipitation persists overnight before gradually weakening below 20 dBZ the next morning, particularly over the lowland area, as shown by the black line. Similarly, Fig. 3d exhibits a nearly identical pattern, with convective rainfall developing in the afternoon, followed by widespread stratiform precipitation lasting through the night before weakening in the morning. In Case 2, the occurrence of convective rainfall is seen to be later than in a previous study39 at around 17 LT (Fig. 2c). It suggests that the season regulates the timing of stratiform and convective forms of rainfall41 over the region.

It is noteworthy that during Case 1, a prolonged stratiform rainfall over the lowland is prominent, and this might induce severe floods over Greater Jakarta (Fig. 2a). Flood is potentially exacerbated by large amounts of rainfall caused by a high concentration of rainfall drops in a large diameter over the mountainous region due to the convective activity (Fig. 2b). We speculated that due to limited holding river capacity, overflow water over the Ciliwung River source (over the mountain) commonly happens and is distributed to the downstream regions in Greater Jakarta. This condition often amplifies the flood risk over the Jakarta region42. However, further analysis shall be thoroughly investigated, for example, considering delineated watersheds and their respective contributing areas.

Different from Case 1, the stratiform rainfall might not be predominant over the lowland in Case 3 (Fig. 2d). During Case 3, mixed convective and stratiform rainfall has the most significant contribution to the total rainfall (Table 1). Unlike Case 1, where the timing of rainfall peaks begins from the afternoon (16 LT on 31 December 2019) to the afternoon the following day (13 LT on 1 Jan 2020), the occurrence of rainfall in Case 3 is more instantaneous, with the highest number of drops and largest diameter observed only in the afternoon (13–16 LT). Over the mountain, convective and stratiform rainfall have nearly the same contribution to total rainfall (around 35%, see Table 1). This result shows the convective rainfall is quite dominant in the mountain.

Rainfall drop size distribution in different types of rain

Figure 4a describes the mean DSDs for all types of rainfall in both sites. In general, both lowland and mountainous regions have similar key features, aligning with findings from previous studies35. The DSD spectrum for both sites indicates that the smaller drops dominate the rainfall for each case. However, Bogor tends to experience a higher number of larger drops compared to Serpong. During the transition to the wet season in mountainous area (Case 3), the raindrop concentration (N(D)) is higher for large drop sizes, and lower for small drop sizes compared to the other cases in Serpong and Bogor.

Gamma function of DSD for all types of rainfall (a), stratiform rainfall (b), and convective rainfall (c) during the three flood cases: 31 December 2019–1 January 2020 (Case 1, red line), 15–16 July 2022 (Case 2, blue line), and 6–12 October 2022 (Case 3, green line) observed by LPM in Serpong (solid) and Bogor (dot-dashed).

Figure 4b and c demonstrate DSD spectrum profiles for each rainfall category, highlighting the distinction between stratiform and convective rainfall. Stratiform rainfall exhibits a relatively higher N(D) for smaller drops and a lower N(D) for larger drops compared to convective rainfall. Figure 4 also indicates a significant difference in the number of larger drops (D > 3 mm) between the two rainfall categories; with convective rainfall producing more larger drops than stratiform rainfall.

During Case 3 in Bogor, the gamma function of the DSD spectrum for convective rainfall (Fig. 4c) closely resembles that of all rainfall types (Fig. 4a, blue dashed line). This finding suggests that precipitation in the mountainous region during that season was likely dominated by convective rainfall. However, this conclusion is based on a single case, and no further climatological analysis has been conducted.

Table 2 shows the integral parameters for each rainfall type. In Case 1, the accumulated time of samples for the stratiform rainfall over the lowland (Serpong) is 909 minutes, with 36.69 mm of total rainfall. For the convective rainfall, the accumulated time of samples is only 255 minutes, with a higher total rainfall (47.79 mm). Likewise, in the mountainous region, in Case 1, stratiform rainfall events have a longer duration than the convective rainfall events. However, convective rainfall produces higher intensity than stratiform rainfall. According to the data from Tables 1 and 2, stratiform rainfall is predominant in Cases 1, 2 and 3 in the lowland area. However, in Case 3, over the mountainous region, convective rainfall is more dominant. This condition may cause flooding in the Jakarta area, with such an accumulated time of convective rainfall and rainfall amounts of 523 minutes and 335.43 mm, respectively, and the rainfall intensity of 138.74 mm h−1.

Rainfall development mechanism

During Case 1, over the lowland region (Serpong), the LPM recorded the rainfall event from 15 LT on 31 December 2019 to 16 LT on 1 January 2020. The ERA5 data shows the CAPE anomaly peaking at 1062 J kg−1 at 14 LT around one hour before the precipitation, suggesting pre-existing deep convective potential. Following this peak, CAPE anomaly decreased to 386 J kg−1 and in general continued to decline gradually, exhibiting moderate to low values coincided with the timing of the recorded precipitation. The MVIMD anomaly remained positive then dropped to − 1.1 g m−2 s−1 indicating strong moisture convergence accompanied by a significant decrease in vertical velocity by − 1.10 Pa s−1 at 17 LT on 31 December 2019, suggesting strong upward motion. The combination of moderate to low CAPE anomaly, significant vertical velocity (w) upward motion, and strong moisture convergence (MVIMD) suggests a stable atmospheric environment with limited convective potential. In this condition, the rainfall is more likely to be associated with large-scale ascent or synoptic scale forcing rather than a strong dynamic lifting. The LPM data also suggests that that stratiform rainfall was the responsible driver in generating this flood event (see Fig. 2a). Although the LPM detected rainfall on 1 Jan at 07–13 LT, the background environment was not necessarily conducive for rainfall development, as indicated by low CAPE and a slight increase of w (Fig. 5a). However, a relatively low MVIMD was observed during this time which might indicate that moisture convergence still existed for the rainfall initiation. The pre-existing large negative anomaly of MVIMD on 31 December at 17 LT likely contributed to the persistence of stratiform cloud until 1 Jan 2020 at 13 LT. As a result, light rainfall still existed until 15 LT on 1 Jan 2020, which was also observed by weather radar (see Figure 3a).

Anomaly of mean vertically integrated moisture divergence (MVIMD) (blue line); vertical velocity (w) (green line); anomaly of Convective Activity Potential Energy (CAPE) (red line), and rainfall from disdrometer data (grey bar chart) presented for different cases and locations. Panels (a) and (b) represent Case 1 in Serpong (lowland) and Bogor (mountain), respectively. Panel (c) shows Case 2 in Serpong. Panels (d), (e) and (f) represent Case 3 in Serpong and Bogor.

During Case 1, over the mountainous region, the high rainfall started earlier, from 12 LT on 31 December 2019 and lasted until 1 January 2020. At 12 LT on 31 December 2019 a substantial negative vertical velocity (− 0.76 Pa s−1) indicated strong vertical motion. At the same time, the MVIMD value peaked at − 0.6 g m−2 s−1, suggesting that the moisture converges in this area. The CAPE anomaly also increased during this hour by around 546 J kg−1 and reached a peak of 640 J kg−1 at 14 LT. After that, the values fluctuated until 19 LT, indicating a constant instability which is also favourable for the development of the convective activity (Fig. 5b). The mountainous terrain over Bogor might enhance atmospheric instability and trigger convective processes due to the orographic effect on the rainfall at 17 LT on 31 December 2019. This result is further confirmed by the analysis of LPM data in Fig. 2b which illustrates the peak of convective rainfall that happened during 14 LT coinciding with the peak of CAPE value. After 19 LT, the atmosphere began stabilising, with lower CAPE and reduced vertical motion, leading to light precipitation indicating a transition toward stratiform rain. However, at 06 LT on 1 January 2020, intense rainfall resumed with 33.48 mm precipitation, driven by a significant increase of CAPE, strong vertical ascent (− 0.48 Pa s−1) and moisture convergence until finally dissipated at 14 LT on 01 January 2020. In general, the rainfall mechanism in Bogor transitioned from intense convective rainfall followed by widespread stratiform rain.

During Case 2, over the lowland region, the high rainfall occurred from 17 LT on 15 July 2022 to 13 LT on 16 July 2022 (Fig. 2c). Negative CAPE was observed throughout this period, indicating a lower-than-normal potential for convective activity. However, the vertical velocity indicated strong upward motion, and the moisture convergence anomaly fluctuated, with negative values particularly between 17–21 LT during the rainfall peaks, indicating periods of moisture convergence. This suggest that the lifting mechanism indicated by the negative value of w and MVIMD was primarily driven by the mesoscale or synoptic scale drivers. As a result, the dominant rainfall type during this period was stratiform and mixed, with convective rainfall accounting for the smallest proportion (18.75%, Table 1), aligns with the observed low CAPE anomaly (Fig. 5c).

In Case 3 during 6–7 October 2022, the LPM data recorded that stratiform rainfall over the lowland is more dominant compared to the mountain region (Table 1). Over the lowland at 12 LT on 6 October 2022, CAPE anomaly briefly turned positive (55 J kg−1), coinciding with increasing moisture convergence and strong upward motion, leading to rainfall peaking at 14 LT (19.47 mm). The combination of a slight increase of CAPE anomaly, a moderate moisture convergence, and strong upward motions during 12–15 LT on 6 October 2022 might indicate the development of convective cloud (Fig 2d). Afterward, as the instability and vertical motion weakened, the rainfall decreased. From 15 to 18 LT on 7 October 2022, an upward motion (negative w) appears (Fig. 5d) at the same time with a small diameter of stratiform rainfall drop (Fig. 2d). In general, over the mountain, the CAPE anomalies, moisture convergence and the vertical velocities are showing a similar trend, indicated the rainfall started in the afternoon by a convective activity followed by widespread rainfall. Despite the similarity, the CAPE anomaly is slightly higher and shows a sharper decline following the rain, the MVIMD suggesting a stronger moisture convergence, and instability compared to the lowland leading to more intense localised rainfall (Fig 5e).

During 11–12 October 2022 (Case 3), no rainfall is observed over the lowland area (Supplementary Fig. S1 online), which is supported by the environmental condition. For example, at 14 LT on 11 October 2022, the maximum value of CAPE anomaly is relatively low, with a moderate ascending velocity, and the limited moisture availability in Serpong, which is possibly not favourable for further cloud development. At 04 LT and 15–19 LT on 12 October 2022, the ERA5 data also shows the combination of low CAPE and moisture divergence.

During Case 3, over the mountain, the underlying condition during the flood is quite different from the lowland. In general, over the mountain, the high positive values of CAPE anomaly (up to 1473 J kg−1, Fig. 5f) seem to generate more convective rainfall, with its anomaly intensity being almost four times higher than the highest CAPE anomaly over the lowland (358 J kg−1). This convective activity might be strengthened by a high anomaly of moisture convergence and followed by a strong vertical ascent. For example, at 14 LT on 11 October 2022 around one hour before the rainfall peak (86.3 mm), CAPE anomaly reaches the maximum value at around 1473 J kg−1 (w) of − 1.45 Pa s−1 and an intense moisture convergence anomaly of − 2 g m−2 s−1, indicating a towering cumulus cloud (Fig. 5f). Almost similar patterns were also observed during the rainfall on 12 October 2022. This suggests rainfall on both days was driven by moisture convergence and strong upward motion, likely leading to deep convective clouds during peak rainfall hours. The MVIMD, CAPE, and ω anomaly plot for all cases can be found in Supplementary Figs. S2–S25 online.

Discussion

This study investigated detailed rainfall types that might contribute to severe flood events on 31 December 2019 to 1 January 2020 (Case 1), 15 to 16 July 2022 (Case 2), and 6 to 12 October 2022 (Case 3) in Jakarta and its surrounding areas, represented by lowland (Serpong) and mountainous (Bogor) regions. Results show that the rainfall drop size generally reaches 4 mm during the peak of flood in those two locations observed by the LPM. The most noticeable feature is that in Case 1, where floods occur during the wet season, rainfall associated with the flood generally originates from a long-duration stratiform rainfall with a low intensity (up to 2 mm). It can be observed from LPM observations that stratiform rainfall continuously occurs from the afternoon of the 31st of December 2019 to the afternoon of the following day (1 January 2020). In Case 1, the stratiform contributes around 58% over the lowland and 48% over the mountainous regions (Table 1). Like case 1, the stratiform rainfall also dominantly exists during case 2 (51%) over the lowland (Table 1). Meanwhile, in case 3, the relative contribution of mixed stratiform and convective rainfall is prevalent over the lowland, and nearly the equal contribution of stratiform and convective rainfall is observed over the mountainous regions (Table 1). Different from the rainfall characteristics found in Case 1, in the dry (Case 2) and transitional (Case 3) seasons, the convective and stratiform rainfall over the lowland is not continuous (Fig. 2c and d). However, the pattern is relatively like the rainfall observed in the previous study39, which states that the convective rainfall takes place in the afternoon (16 LT) and shifts to the stratiform rainfall between evening (19 LT) and midnight (00 LT). However, a slightly different peak timing of stratiform and convective rainfall is found, for example, they occur within 1–3 hours later, as observed in Case 2 and 1–3 hours ahead, as observed in Case 3. The difference in timing of the peak of stratiform and convective rainfall found in this study implies that the season in the Jakarta area is one of the controlling factors for the development of stratiform and convective rainfall, as found by a previous study41. When floods occur, it is clearly shown that convective rainfall in the afternoon produces a droplet size of more than 4 mm.

In the three flood cases, we found that convective rainfall has a higher concentration of large droplets than stratiform rainfall (Fig. 4b and c), and it has a similar finding with previous research14,27,43. One intriguing finding is that the concentration of large rainfall droplets in the mountainous area (Bogor) is higher than in the lowland area (Serpong), as shown in Fig. 2a. Furthermore, this finding is mainly found in the stratiform rainfall if we compare the µ, Dm parameter in Serpong and Bogor as shown in Table 2. The µ and Dm values in the lowland for all 3 cases range from 4.33 to 4.41 and 1.31 to 1.54 mm, respectively. These values are relatively smaller compared to the value observed in Bogor, which ranges from 4.98 to 5.00 and 1.49 to 1.59 mm for µ and Dm, respectively. Nevertheless, among the three flood cases, the contribution of convective rainfall over the mountainous area is highest in Case 3, which occurred in October 2022. In addition, during the wet season, as in Cases 1 and 3, the concentration of larger raindrops (diameter up to 4 mm) associated with convective rainfall is notably observed over the mountainous regions. During Cases 1 and 3, the convective rainfall over the mountain might be influenced by a continuous anomaly of positive CAPE both in Case 1 (31 December 2019 at 10 LT and 1 January 2020 at 08 LT) and Case 3 (11 October 2022 at 14 LT and 12 October 2022 at 13 LT) as shown in Fig. 5b and e, respectively.

Our result has shown that the characteristics of rainfall during flood events come from different physical characteristics. The stratiform rainfall is more predominant over the lowland than the mountainous region, and it might be one of the major causes of the Jakarta flood. A relatively small intensity but overnight stratiform rainfall has led to uncommonly high accumulated rainfall intensity, likely causing a severe flood over the Jakarta region as happened during Case 1. Conversely, over the mountainous areas (upper stream river), convective rainfall in a relatively short period might result in high surface runoff over the narrow river, as occurred in Case 3. This overflow is subsequently transported to the downstream river near Jakarta, which resulted in more severe flooding, as observed in Case 1. This observation aligns with42 who documented significant influence of diurnal rainfall patterns on diurnal water level variations in the Ciliwung River, West Java, Indonesia. In Case 1, the combination of CENS and atmospheric waves caused wet moisture to converge10, which led to the development of significant stratiform rainfall over the Jakarta area from the lowland in the north to the mountainous region in the south. In addition, minor activity of convective rainfall was observed in the mountainous region in the south. These two rainfall types then led to a flood disaster in Jakarta. For Case 2, a high negative anomaly of MVIMD indicates a moisture convergence area in the Jakarta area that induces some stratiform and convective rainfall development. Even though the stratiform rainfall is not as much as in Case 1, it might be one of the driving factors that cause flooding in Jakarta. Meanwhile, in Case 3, a robust convective rainfall that occurs in the upstream area in the mountainous area (south of Jakarta) shall contribute to a flood disaster over the capital city located in a downstream area44,45. Although the convective rainfall over the mountainous area might increase the risk of flood, some stratiform rainfall occurring over Serpong (lowland) is also observed during Case 3, and these simultaneous activities might intensify the flood risk in the capital city. We recognize that relying solely on local rainfall measurements may not adequately address the comparison of flooding events in lowland and mountainous regions. For instance, it is essential to include delineated watersheds and their respective contributing areas in our analysis. However, this aspect is beyond the scope of our current study and will be addressed in future research.

The different features of the climatology of N(D) between lowland and mountainous regions during the wet season (December–January–February from 2019 to 2021) are compared as a gamma function of DSD in Fig. 6 (red and blue solid lines representing Serpong and Bogor, respectively). This season was selected because it generally experiences the most severe flood impacts. This figure indicates that the N(D) curve over both regions has no distinctive patterns. For example, the diameter that falls between 5 and 6 mm has the number of raindrop density of around 10−6 m−3 mm−1 over lowland and mountainous regions for stratiform (Fig. 6a) and around 10−2 m−3 mm−1 for convective (Fig. 6b). However, the gamma function graphs for DJF show a similar pattern to that in the flood event depicted in Figure 4b and c, in which convective rainfall is characterised by a higher concentration of large droplets compared to stratiform. Nonetheless, in these two graphs, the distribution of raindrops in the lowlands and highlands is nearly identical. In comparison to the DSD spectrum during the flood event in case 1 (dashed line in Figure 6), the N(D) value for stratiform rainfall is higher throughout all droplet diameters but lower for convective. This suggests that during the flood event in case 1, stratiform rainfall predominates in extended duration in both areas.

Results of this study have shown that high rainfall intensity is not only the main factor causing flooding in the Jakarta region. Light and moderate rainfall with long-duration clearly contribute to rainfall in total that can induce the risk of flood. Understanding the physical characteristics of the rainfall measured by combined instruments of rainfall observations, such as using very high spatial and time resolutions of weather radar, LPM, and observation station datasets, is crucial, especially for the Indonesian region, with the nature of the rainfall being markedly local and topographically complex. Previous studies have not comprehensively examined the physical characteristics of rainfall related to flood events over Jakarta. This research shall provide fundamental knowledge of better predicting surface runoff over the upper and downstream areas based on the type of rainfall and timing of the peak. The main aim is to minimise the risks of flood disasters over Jakarta and its surrounding regions.

Considering the proximity between the Serpong and Bogor regions (approximately 60 km), the coarse spatial and temporal resolutions of ERA5 data may not accurately represent the local meteorological conditions during the development of stratiform and convective rainfall. Despite this limitation, the ERA5 dataset has reasonably illustrated the background conditions for rainfall development in this study. However, further research using local atmospheric-sounding data is necessary to gain a more detailed understanding of the surrounding meteorological background. This is particularly important when considering the influence of large-scale drivers, such as the Madden–Julian Oscillation and the Cross Equatorial Northerly Surge (CENS), which are known to influence changes of stratiform rainfall in the region. Investigating these factors, especially during the wet season, is imperative. In addition, studying the climatology of the physical characteristics of rainfall (both stratiform and convective) over Jakarta, seasonally and diurnally, using extended timescale datasets and analysing the spatial characteristics of their physical properties with weather radar, would be an important topic for future research.

This study only focuses on understanding the physical characteristics of rainfall during the flood events and investigating the underlying mechanisms or phenomena possibly shaping those characteristics. This article does not examine the causal factors of flooding in the study area. Several previous studies have provided more detailed analyses of the causes of flooding in the Greater Jakarta area (Jabodetabek), which primarily lies within the Ciliwung River Basin. These include factors such as climate change and extreme rainfall46,47,48, land use change49,50, topography51, as well as numerous other contributing factors such as human activities and urbanization. Further and more comprehensive research is necessary to better elucidate the relationship between rainfall events and flood occurrences.

Data availability

LPM Disdrometer data generated during and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Rainfall data recorded from the Automatic Weather Station (AWS) and Maximum Reflectivity (CMAX) images from weather radar are obtained from BMKG. ERA5 hourly reanalysis data on single level and pressure levels are available through Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) (2023): ERA5 hourly data on single levels and pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47; https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6 (Accessed on 28 February 2023).

References

Ramage, C. S. Role of a tropical “maritime continent” in the atmospheric circulation. Mon. Weather Rev. 96, 365–370 (1968).

Slingo, J., Inness, P., Neale, R., Woolnough, S. & Yang, G. Scale interactions on diurnal to seasonal timescales and their relevanceto model systematic errors. Annals Geophys. 46, (2003).

Firman, T., Surbakti, I. M., Idroes, I. C. & Simarmata, H. A. Potential climate-change related vulnerabilities in Jakarta: Challenges and current status. Habitat Int. 35, 372–378 (2011).

BNPB. Geoportal data Bencana Indonesia (Indonesian Disaster Data Geoportal). 2023 https://gis.bnpb.go.id.

Wu, P. et al. The impact of trans-equatorial monsoon flow on the formation of repeated torrential rains over Java Island. SOLA 3, 93–96 (2007).

Wu, P. et al. The effects of an active phase of the Madden-Julian oscillation on the extreme precipitation event over Western Java Island in January 2013. SOLA 9, 79–83 (2013).

Kurniadi, A., Weller, E., Min, S. & Seong, M. Independent ENSO and IOD impacts on rainfall extremes over Indonesia. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 3640–3656 (2021).

Hattori, M., Mori, S. & Matsumoto, J. The cross-equatorial northerly surge over the maritime continent and its relationship to precipitation patterns. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan Ser. II 89A, 27–47 (2011).

Yulihastin, E., Hadi, T. W., Ningsih, N. S. & Syahputra, M. R. Early morning peaks in the diurnal cycle of precipitation over the northern coast of West Java and possible influencing factors. Ann. Geophys. 38, 231–242 (2020).

Lubis, S. W. et al. Record-breaking precipitation in Indonesia’s Capital of Jakarta in Early January 2020 linked to the Northerly Surge, equatorial waves, and MJO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL101513 (2022).

Lestari, S. et al. Variability of Jakarta Rain-Rate characteristics associated with the Madden–Julian oscillation and topography. Mon. Weather Rev. 150, 1953–1975 (2022).

Marzuki, M. et al. Comparison of vertical profile of raindrop size distribution from micro rain radar with global precipitation measurement over Western Java Island. Remote Sens. Appl. 29, 100885 (2023).

Sauvageot, H. & Lacaux, J.-P. The shape of averaged drop size distributions. J. Atmos. Sci. 52, 1070–1083 (1995).

Wu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Zheng, H. & Huang, X. A comparison of convective and stratiform precipitation microphysics of the record-breaking Typhoon In-Fa (2021). Remote Sens. (Basel) 14, 3445 (2022).

Houze, R. A. Nimbostratus and the separation of convective and stratiform precipitation. In International Geophysics Vol. 104 (Elsevier, 2014).

Thomas, A., Kanawade, V. P., Chakravarty, K. & Srivastava, A. K. Characterization of raindrop size distributions and its response to cloud microphysical properties. Atmos. Res. 249, 105292 (2021).

Han, Y. et al. Regional variability of summertime raindrop size distribution from a network of disdrometers in Beijing. Atmos. Res. 257, 105591 (2021).

Konwar, M., Das, S. K., Deshpande, S. M., Chakravarty, K. & Goswami, B. N. Microphysics of clouds and rain over the Western Ghat. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 6140–6159 (2014).

Kozu, T., Shimomai, T., Akramin, Z., Shibagaki, Y. & Hashiguchi, H. Intraseasonal variation of raindrop size distribution at Koto Tabang, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL022340 (2005).

Kozu, T. et al. Seasonal and diurnal variations of raindrop size distribution in Asian monsoon region. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan Ser. II 84A, 195–209 (2006).

Renggono, F. et al. Raindrop size distribution observed with the Equatorial Atmosphere Radar (EAR) during the Coupling Processes in the Equatorial Atmosphere (CPEA-I) observation campaign. Radio Sci. 41, RS5002 (2006).

Marzuki, F. et al. Raindrop size distributions of convective rain over equatorial Indonesia during the first CPEA campaign. Atmos. Res. 96, 645–655 (2010).

Marzuki, et al. Raindrop axis ratios, fall velocities and size distribution over Sumatra from 2D-Video Disdrometer measurement. Atmos. Res. 119, 23–37 (2013).

Marzuki, M., Hashiguchi, H., Yamamoto, M. K., Mori, S. & Yamanaka, M. D. Regional variability of raindrop size distribution over Indonesia. Ann. Geophys. 31, 1941–1948 (2013).

Marzuki, et al. Precipitation microstructure in different Madden–Julian Oscillation phases over Sumatra. Atmos. Res. 168, 121–138 (2016).

Marzuki, M. et al. Land – sea contrast of diurnal cycle characteristics and rain event propagations over Sumatra according to different rain duration and seasons. Atmos. Res. 270, 106051 (2022).

Ramadhan, R., Vonnisa, M., Hashiguchi, H. & Shimomai, T. Diurnal variation in the vertical profile of the raindrop size distribution for stratiform rain as inferred from micro rain radar observations in Sumatra. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 37, 832–846 (2020).

Vonnisa, M., Shimomai, T., Hashiguchi, H. & Marzuki, M. Retrieval of vertical structure of raindrop size distribution from equatorial atmosphere radar and boundary layer radar. Emerg. Sci. J. 6, 448–459 (2022).

Aldrian, E. & Susanto, R. D. Identification of three dominant rainfall regions within Indonesia and their relationship to sea surface temperature. Int. J. Climatol. 23, 1435–1452 (2003).

Hamada, J.-I. et al. Spatial and temporal variations of the rainy season over Indonesia and their Link to ENSO. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn 80, 285–310 (2002).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Wessel, P. et al. The generic mapping tools version 6. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5556–5564 (2019).

NASA JPL. NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Global 3 arc second. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center. https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/srtmgl3v003/ (2013) https://doi.org/10.5067/MEaSUREs/SRTM/SRTMGL3.003.

Brandes, E., Zhang, F. & Vivekanandan, J. Experiments in rainfall estimation with a polarimetric radar in a subtropical environment. J. Appl. Meteorol. 41, 674–685. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(2002)041 (2002).

Pu, K. et al. A comparison study of raindrop size distribution among five sites at the urban scale during the East Asian rainy season. J. Hydrol. (Amst) 590, 125500 (2020).

Chen, B., Yang, J. & Pu, J. Statistical characteristics of raindrop size distribution in the Meiyu season observed in Eastern China. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan Ser. II 91, 215–227 (2013).

Ulbrich, C. W. Natural variations in the analytical form of the raindrop size distribution. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 22, 1764–1775 (1983).

Trenberth, K. E., Dai, A., Rasmussen, R. M. & Parsons, D. B. The changing character of precipitation. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 84, 1205–1218 (2003).

Katsumata, M. et al. Diurnal cycle over a coastal area of the Maritime Continent as derived by special networked soundings over Jakarta during HARIMAU2010. Prog. Earth Planet Sci. 5, 1–19 (2018).

Mori, S. et al. Meridional march of diurnal rainfall over Jakarta, Indonesia, observed with a C-band Doppler radar: An overview of the HARIMAU2010 campaign. Prog. Earth Planet Sci. 5, 1 (2018).

Yang, S. & Smith, E. A. Convective-stratiform precipitation variability at seasonal scale from 8 Yr of TRMM observations: Implications for multiple modes of diurnal variability. J. Clim. 21, 4087–4114 (2008).

Sulistyowati, R. et al. Rainfall-driven diurnal variations of water level in the Ciliwung river, West Jawa, Indonesia. Sci. Online Lett. Atmos. 10, 141–144 (2014).

Steiner, M. & Smith, J. A. Convective versus stratiform rainfall: An ice-microphysical and kinematic conceptual model. Atmos. Res. 47–48, 317–326 (1998).

Stingl, S. Resilience of urban systems in the face of natural hazards: To what extent do humanitarian organisations contribute to flood preparedness in Jakarta? (Uppsala University, 2018).

JICA. The Simulation Study on Climate Change in Jakarta, Indonesia. https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12150942.pdf (2012).

Emam, A. R., Mishra, B. K., Kumar, P., Masago, Y. & Fukushi, K. Impact assessment of climate and land-use changes on flooding behavior in the upper Ciliwung river, Jakarta, Indonesia. Water (Switzerland) 8, 559 (2016).

Asdak, C., Supian, S. & Subiyanto,. Watershed management strategies for flood mitigation: A case study of Jakarta’s flooding. Weather Clim. Extrem. 21, 117–122 (2018).

Sulistyowati, R. et al. Distributed flood simulation based on satellite rainfall data at the Ciliwung River Basin, Jawa, Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science vol. 1127 (2023).

Remondi, F., Burlando, P. & Vollmer, D. Exploring the hydrological impact of increasing urbanisation on a tropical river catchment of the metropolitan Jakarta, Indonesia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 20, 210–221 (2016).

Moe, I. R. et al. Future projection of flood inundation considering land-use changes and land subsidence in Jakarta, Indonesia. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 11, 99–105 (2017).

Ariyani, D., Purwanto, M. Y. J., Sunarti, E. & Perdinan,. Contributing factor influencing flood disaster using MICMAC (Ciliwung Watershed Case Study). J. Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Alam dan Lingkungan 12, 268–280 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP19H01378 and JP20K21852, corresponding to the Jakarta Heavy Rainfall Experiment (JaHE) (JFY 2019–2023) and the Development of Maritime Continent automatic dependent Air-sea observation Network (MaCAN) projects respectively. The authors would like to acknowledge the Indonesian Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysical Agency (BMKG) for providing the Automatic Weather Station (AWS) and Weather Radar imageries. The authors also thank the National Laboratory for Weather Modification BRIN, Geospatial Research (PRG) BRIN, and the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Sciences and Technology (JAMSTEC) for providing the LPM data at Serpong and Bogor. Hersbach, H. et al., (2023) was downloaded from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) (2023). The results contain modified Copernicus Climate Change Service information 2020. Neither the European Commission nor ECMWF is responsible for any use that may be made of the Copernicus information or data it contains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. Renggono, S. Lestari, H.A. Belgaman, R. Syahdiza, S. Dewi, designed conceptualization, methodology and wrote the manuscript; F. Renggono, S. Lestari, S. Dewi performed LPM Disdrometer data processing; H.A. Belgaman, and R. Syahdiza performed ERA5 data processing; B. Harsoyo, B. Budianto, R. Sulistyowati and N. Nurdiansyah performed disdrometer data acquisition; H. J. W. Argo performed radar data acquisition; S. Mori, F. Syamsudin, R. Sulistyowati, E. Mulyana and E. Riawan reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Renggono, F., Lestari, S., Belgaman, H.A. et al. Rainfall microphysical characteristics observed in the Jakarta flood events. Sci Rep 15, 33879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08328-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08328-0