Abstract

Phenol, a persistent toxicant in industrial effluents, poses a risk to ecosystems and public health. As an environmentally sustainable solution, microbial bioremediation has gained attention. In this study, next-generation whole-genome sequencing was performed on two phenol-degrading halophilic bacteria, PT-11 and PT-20. Strain PT-11 encoded 10 key genes related to phenol degradation, compared to 9 key genes in strain PT-20. Notably, strain PT-11 possessed two genes for catechol 1, 2-dioxygenase, which was involved in the ortho-cleavage pathway. In contrast, strain PT-20 contained two genes for catechol 2, 3-dioxygenase, which was associated with the meta-cleavage pathway. These findings suggested that the complementary metabolism between the two strains might enhance phenol degradation. The mixed strains demonstrated remarkable efficiency in phenol degradation under hypersaline conditions (5% NaCl), achieving complete phenol degradation within 42 h at 800 mg/L, 54 h at 1000 mg/L, and 72 h at 1200 mg/L. Moreover, the mixed strains showed high efficiency in remediation of soil contaminated with 5% NaCl and 300 mg/kg phenol, with rapid reduction in phenol content within 48 h and full degradation by 72 h. Soil microbial diversity analysis showed that the relative abundance of Oceanobacillus peaked at 95.59% at 0 h, slightly dropped to 94% at 24 h, and significantly decreased to 21.15% by 72 h. As phenol content decreased over time, the community composition diversified and gradually resembled that of the blank control group. Overall, these findings demonstrated the potential of these halophilic bacteria for bioremediation of phenol-contaminated environments, particularly in high-salinity conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phenol is a highly toxic and persistent industrial pollutant released from various industrial processes, including textile processing, oil refining, leather manufacturing, resin synthesis, and perfume production1. It is both highly toxic and poorly degradable, posing significant environmental and health risks, including mutagenesis and carcinogenesis2. Due to its widespread use in industrial applications, phenol inevitably contaminates water and soil, contributing to the pollution of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Even at low concentrations, phenol can cause substantial ecological harm due to its high toxicity3. Furthermore, phenol tends to accumulate in the environment and reacts readily with other organic compounds to form even more toxic phenolic derivatives, such as chlorophenols, methylphenols, and alkylphenols4. The toxicity of these phenolic compounds varies depending on their structure and functional groups, and they tend to be more persistent and recalcitrant, complicating remediation efforts and increasing the potential health risks5,6. Traditional physical and chemical methods for treating phenol-contaminated soil, like ozonation, the Fenton reaction, ultraviolet irradiation, and hydrogen peroxide treatment, are often costly and environmentally harmful7. In contrast, microbial remediation, which leverages microorganisms’ metabolic abilities to degrade phenol into harmless compounds8, has garnered growing interest. This approach is more cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and easier to implement, making it a promising solution for pollution control.

Phenol pollution is frequently associated with high salinity, which significantly increases the difficulty of microbial degradation. High salinity conditions can inhibit the activity of many phenol-degrading microorganisms, making it challenging to achieve efficient bio-remediation9. Therefore, isolating microbial strains capable of both high salinity tolerance and efficient phenol degradation is essential for the biological treatment of high-salinity phenol-contaminated environment. For instance, the novel salt-tolerant phenol-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas sp. SAS26 exhibited robust phenol-degrading capabilities even under high salinity (up to 30 g/L NaCl), achieving complete degradation of 1500 mg/L phenol within 60 h, with the highest degradation rate of 0.360 g/(g CDW·h) observed at approximately 24 h under a higher NaCl concentration of 30 g/L10. Additionally, Bacillus paralicheniformis BL-1, a bioflocculant-producing bacterium, showed phenol degradation at high salinity, achieving a 73.83% phenol removal rate in the synthetic medium (supplemented with 10% NaCl, 500 mg/L phenol, and 250 μM FeCl3)11. A halophilic strain of Citrobacter was also capable of withstanding high phenol (up to 1,100 mg/L) environment under varying salinity conditions (0–10% NaCl), with complete degradation of 400 mg/L phenol within 20 h under hypersaline conditions12. In addition, several other strains, such as Halomonas organivorans13, Debaryomyces sp. JS414, Candida sp. JS315, and Halomonas sp. PH2-216, have also demonstrated phenol-degrading capabilities in high-salinity environments.

The aerobic microbial degradation of phenol has been extensively studied, with a particular focus on the key initial step: the oxidation of phenol to catechol by phenol hydroxylase (PH), which is rate-limiting in the entire phenol metabolism pathway17. Catechol, an important intermediate in the peripheral pathways of aerobic degradation of various aromatic compounds in bacteria18, undergoes ring-opening cleavage via two major pathways: the ortho and meta pathways19,20. These pathways ultimately generate intermediates that integrate into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, completing phenol metabolism. In the ortho metabolic pathway, catechol is catalytically cleaved by catechol-1, 2-dioxygenase (C12O) to form cis, cis-muconic acid. This intermediate is subsequently converted to β-ketoadipate, which undergoes further transformation by the β-ketoadipate pathway into succinate and acetyl-CoA-both key intermediates of the TCA cycle21. In the meta metabolic pathway, catechol is cleaved by catechol 2, 3-dioxygenase (C23O) to form 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde, which is then converted into 4-hydroxy-α-ketoglutarate and ultimately into acetate and pyruvate22. These products are subsequently channeled into the TCA cycle. Current research suggested that the cleavage of catechol primarily follows one of these two metabolic pathways.

In this study, whole-genome sequencing was conducted on two previously isolated phenol-degrading halophiles, Oceanobacillus rekensis PT-11 and Oceanobacillus damuensis PT-20. Their genomes were analyzed for phenol degradation-related genes. The phenol degradation capacity of a mixed PT-11 and PT-20 culture was assessed under high-salinity conditions. Additionally, the mixed bacterial strains were applied to remediate phenol-contaminated saline soil, with monitoring of phenol degradation and changes in soil microbial diversity throughout the bioremediation process.

Material and methods

Materials

Two halophilic species, Oceanobacillus damuensis PT-20 and Oceanobacillus rekensis PT-11 used in this experiment, were isolated from soil and preserved in our laboratory23. Soil samples were collected from an abandoned leather factory site in Xinji, Hebei Province. Tryptone, soy peptone, NaCl, phenol, lysozyme, and other reagents are commercially available.

Culture medium and conditions

The culture medium used was TSB (Tryptone Soy Broth) with 5% NaCl, composed of tryptone (15 g/L), soy peptone (5 g/L), NaCl (50 g/L), and pH 8.0. O. damuensis PT-20 and O. rekensis PT-11 were inoculated into TSB medium with 5% NaCl. The cultivation temperature and stirring were maintained at 200 rpm and 30 °C for 36 h. The bacterial cells were collected from 10 mL of PT-11 and PT-20 cultures (logarithmic growth phase, OD600≈1.6) by centrifugation. Then, the cells were resuspended in 5 mL of culture medium, mixed well in a 1:1 ratio, and used as inoculum for phenol degradation experiments in high-salinity conditions and bioremediation of phenol-contaminated soil.

Genome sequencing and analysis of PT-20 and PT-11

O. damuensis PT-20 and O. rekensis PT-11 were cultured in 100 mL TSB medium with 5% NaCl in shake flasks at 200 rpm and 30 °C for overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and then washed thrice by ultra-pure water. Genomic DNA was isolated from fresh-collected cells and purified as described previously24. DNA quality was assessed by running the sample on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel, and its concentration was quantified by a Nanodrop Life spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The genome of PT-20 and PT-11 was sequenced by using Illumina MiSeq 2500 sequencing platform by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The raw sequence data were processed with Adapter Removal v2.1.7 and reads were assembled by SOAPdenovo v2.0425. Gene prediction was carried out using Glimmer 3.0226. Functional predictions of the ORFs were conducted by searching against multiple databases: non-redundant (NR, http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) 27, Gene Ontology (GO, http://www.geneontology.org/) and Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG, http://eggnog.embl.de/)28.

Phenol degradation performance of PT-20 and PT-11 in high salt environment

Phenol was added to TSB medium with 5% (w/v) NaCl at concentrations of 800 mg/L, 1000 mg/L and 1200 mg/L. Strains PT-20 and PT-11 were inoculated into medium. The cultures were maintained at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Samples (3 mL) were harvested every 6 h. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm, and the growth curves were plotted. The supernatant was collected and analyzed for phenol content by using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with ultraviolet detector.

Phenol-contaminated soil bio-remediation by using mixed bacteria

The soil samples were collected from an abandoned leather factory site in Xinji, Hebei Province. Soil samples were prepared by removing rocks and impurities, air-drying, and passing through a 10-mesh sieve. A 200 g portion of the soil was weighed into a beaker, amended with phenol to achieve a concentration of 300 mg/kg, and inoculated with a mixture of bacterial strains PT-11 and PT-20. The soil moisture content was adjusted to 30%, and the NaCl concentration was set to 5%. The soil was then mixed thoroughly and incubated at 30 °C. Samples were collected every 12 h for analysis. The soil samples without adding bacterial strains were used as blank control group. The phenol content in soil was determined by Headspace-Gas Chromatography (HS-GC). Each treatment was replicated three times.

Soil microbial diversity analysis

Soil samples (2 g) were collected every 12 h, transferred to sampling tubes, and sent to Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for microbial diversity analysis. Total microbial genomic DNA was extracted from soil samples by using the E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.). The DNA quality and concentration were assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, United States). The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primers 338F and 806R. The PCR product was extracted from 2% agarose gel and purified using the PCR Clean-Up Kit (YuHua, Shanghai, China) and quantified using Qubit 4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina Nextseq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). After demultiplexing, the resulting sequences were quality filtered with fastp (0.19.6)29 and merged with FLASH (v1.2.11)30. Then the high-quality sequences were de-noised using DADA231 plugin in the Qiime232 (version 2020.2) pipeline with recommended parameters. DADA2 denoised sequences are usually called amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Taxonomic assignment of ASVs was performed using the Naive bayes consensus taxonomy classifier implemented in Qiime2 and the SILVA 16S rRNA database (v138). The metagenomic function was predicted by PICRUSt233 based on ASV representative sequences.

Bioinformatic analysis of the soil microbiota was carried out using the Majorbio Cloud platform34. Based on the ASVs information, rarefaction curves and alpha diversity indices including observed ASVs, Chao1 richness, Shannon index and Good’s coverage were calculated with Mothur v1.30.135. The similarity among the microbial communities in different samples was determined by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–curtis dissimilarity using Vegan v2.5–3 package. The PERMANOVA test was used to assess the percentage of variation explained by the treatment along with its statistical significance using Vegan v2.5–3 package. The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe)36 was performed to identify the significantly abundant taxa (phylum to genera) of bacteria among the different groups (LDA score > 2, P < 0.05). The distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) was performed using Vegan v2.5–3 package to investigate effect of soil physicochemical properties parameters on soil bacterial community structure. Forward selection was based on Monte Carlo permutation tests (permutations = 9999). Values of the X- and Y-axes and the length of the corresponding arrows represented the importance of each soil physicochemical properties parameters in explaining the distribution of taxon across communities. Linear regression analysis was applied to determine the association between major physicochemical properties parameters identified by db-RDA analysis and microbial alpha diversity indices. The co-occurrence networks were constructed to explore the internal community relationships across the samples37.

Analysis method

Determination of phenol content by HPLC

The chromatographic conditions were as follows: Column, C18 reverse-phase column (Diamonsil, 5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm); mobile phase, methanol: water (50: 50, v/v); flow rate, 0.8 mL/min; detection wavelength, 270 nm; column temperature, 35 °C; injection volume, 20 μL.

Determination of phenol content by HS-GC

Sample preparation A 2-g soil sample was collected for phenol extraction. The sample was mixed with 8 mL of saturated sodium chloride solution and shaken at 200 rpm for 30 min, followed by sonication for 30 min. These shaking and sonication steps were repeated twice. The mixture was then centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for subsequent analysis.

Headspace sampler conditions The headspace sampler conditions were as follows: equilibration temperature, 85 °C; equilibration time, 50 min; sample needle temperature, 100 °C; transfer line temperature, 110 °C; pressure equilibrium time, 1 min; injection time, 0.2 min; needle retraction time, 0.4 min.

Gas chromatograph conditions The gas chromatograph conditions were as follows: column type, HP-5 (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 µm); temperature program, 40 °C for 6 min, then ramped at 5 °C/min to 110 °C and held for 1 min, followed by a ramp at 6 °C/min to 200 °C and held for 3 min; injector temperature, 220 °C; detector temperature, 240 °C; carrier gas, nitrogen; column flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; hydrogen flow rate, 40 mL/min; air flow rate, 400 mL/min; injection method, split injection (split ratio, 10: 1).

Results and discussion

Genome analysis of strain PT-11 and PT-20

In this study, the genomes of two halophilic stains, PT-11 and PT-20, were sequenced by next-generation sequencing based on the Illumina MiSeq platform. The basic sequencing information was summarized in Table 1. The genome sizes of strain PT-11 and PT-20 were 3,865,100 bp and 4,118,651 bp, respectively. These genomes were composed of 21 scaffolds for PT-11 and 75 scaffolds for PT-20. The G + C content of their genomes was 37.5 mol% for PT-11 and 39.3 mol% for PT-20 (Figure S1). These genomic data were submitted to the NCBI database, with GenBank accession numbers MTBQ00000000 for PT-11 and LQNF00000000 for PT-20.

Genomic annotation revealed that strains PT-11 and PT-20 contained 3865 and 4011 genes, respectively. Of these, 3681 and 3875 were protein-coding genes, 112 and 62 were RNA genes, and 72 and 74 were pseudogenes. The KEGG27 database was employed to annotate and cluster the predicted genes of these strains. The results were shown in Fig. 1. In both strains, genes associated with metabolic pathways constituted the largest proportion. Specifically, the abundance of genes related to carbohydrate metabolism and the degradation of xenobiotic compounds provides valuable references for subsequent gene analysis38. Additionally, pathways involved in fatty acid metabolism and the metabolism of amino acid analogs offer insights for further investigation into stress resistance39.

Notably, genes related to environmental adaptation, particularly those involved in membrane transport and signal transduction, accounted for over 5% of the total genes in both strains. This indicated that these halophilic bacteria possessed a robust capacity to rapidly respond to environmental changes. The diversity and abundance of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) are critical determinants of a microorganism’s nutritional versatility and metabolic capacity40. A richer repertoire of CAZymes generally confers a greater ability to adapt to varied environmental conditions41. According to the analysis using the CAZymes Database (http://www.cazy.org/), the genomes of strains PT-11 and PT-20 were found to encode 95 and 97 carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) genes, respectively. This highlights their potential for carbohydrate metabolism and adaptation to diverse environments. The classification results were depicted in Fig. 2. The genomes of PT-11 and PT-20 contained six and five classes of carbohydrate-active enzymes, respectively. Within these enzyme categories, the two genomes exhibited comparable quantities of carbohydrate esterases, glycosyltransferases, carbohydrate-binding modules, and auxiliary activities. The highly similar CAZyme profiles of strains PT-11 and PT-20 suggest that both strains possessed comparable capabilities for carbohydrate metabolism and were likely to thrive under similar nutritional conditions. This shared profile also implied that both strains possessed equivalent types and quantities of glycoside hydrolases, thereby enhancing their ability to utilize carbohydrates. Notably, despite their overall similarity, the genome of PT-20 lacks genes encoding polysaccharide lyases.

KEGG database was utilized to predict the metabolic pathways and key enzyme-encoding genes involved in phenol metabolism. Analysis revealed key genes implicated in the degradation of benzene homologs, with the findings presented in Table 2. The genes involved in phenol degradation tend to be clustered and are located either on large plasmids or within the chromosome42. The preliminary degradation pathway of phenol by aerobic degradation was illustrated in Figure S2. The initial step in phenol biodegradation was the conversion of phenol to catechol by phenol 2-hydroxylase43. Catechol was then degraded through two primary pathways: the ortho-cleavage pathway and the meta-cleavage pathway44.

In the ortho-cleavage pathway, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase cleaved the aromatic ring between the two hydroxyl groups, producing cis,cis-muconate. This compound was then transformed into muconolactone by muconate cycloisomerase45. Muconolactone was subsequently converted to 3-oxoadipate-enol-lactone by muconolactone isomerase and then to 3-oxoadipate by 3-oxoadipate-enol-lactonase. Next, 3-oxoadipate and succinyl-CoA were converted to 3-oxoadipyl-CoA and succinic acid by 3-oxoadipate CoA-transferase. Finally, 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase converted 3-oxoadipyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, which entered the tricarboxylic acid cycle for complete oxidation into carbon dioxide and water46.

In the meta-cleavage pathway, catechol 2,3-dioxygenase converted catechol to 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde47. This compound was then transformed into 4-oxalocrotonic acid by dehydrogenase. Decarboxylase subsequently converted 4-oxalocrotonic acid to 2-oxopent-4-enoate. Hydratase then acted on this compound to form 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate. Finally, aldolase broke down 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate into acetaldehyde and pyruvate. Acetaldehyde was further converted to acetic acid by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetic acid was then catalyzed by acetate kinase and acetyl-CoA synthetase to bind with CoA and form acetyl-CoA. Pyruvate was converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase, releasing CO2 in the process. The acetyl-CoA was subsequently metabolized and integrated into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, completing the degradation process.

Whole-genome analysis of the strains revealed that strain PT-11 encoded 10 genes related to phenol degradation enzymes, while strain PT-20 encoded 9 such genes. Specifically, strain PT-11 contained two genes encoding catechol 1, 2-dioxygenase, indicating a preference for the ortho pathway in phenol degradation. In contrast, strain PT-20 contained two genes encoding catechol 2, 3-dioxygenase, suggesting a stronger inclination towards the meta pathway48. Despite these differences, both strains were capable of degrading phenol through both ortho and meta pathways. Moreover, strain PT-11 harbored two genes encoding ring-cleaving dioxygenase and one gene encoding 4-hydroxybenzoate decarboxylase. Strain PT-20, on the other hand, contained one gene encoding ring-cleaving dioxygenase and one gene encoding 4-nitrophenol 2-monooxygenase, indicating that these strains may have evolved to handle specific aromatic substrates, enhancing their metabolic versatility. The remaining genes related to phenol degradation were similar between the two strains. Understanding the genetic basis of phenol degradation in strains PT-11 and PT-20 offers important insights for bioremediation. Strain PT-11, with its robust ortho pathway, and strain PT-20, with its emphasis on the meta pathway, both emerge as valuable candidates for bioremediation in complex environments, such as contaminated soil or mixed-waste sites. Combining these strains into microbial consortia could enhance phenol degradation efficiency, offering a robust solution for industrial waste treatment22.

The effects of phenol on bacterial growth and phenol degradation in high salt environment

The growth and phenol degradation of mixed strains were measured in 5% (w/v) NaCl, and the results were shown in Fig. 3. During the first 12 h, the mixed bacterial strains exhibited slow phenol degradation and growth at initial phenol concentrations of both 800 mg/L and 1000 mg/L. Subsequently, phenol degradation accelerated, with near-complete depletion occurring by 42 h at 800 mg/L and by 48 h at 1000 mg/L. The optical density (OD600) of mixed bacteria increased from 1.159 to 3.348 at 800 mg/L and from 1.053 to 3.355 at 1000 mg/L phenol, indicating robust bacterial growth. At an initial phenol content of 1200 mg/L, phenol degradation was slow during the first 24 h, with the OD600 of the mixed bacteria reaching 1.823. From 24 to 72 h, the degradation rate accelerated, and the phenol content was nearly depleted by 72 h, with the OD600 of the mixed bacteria rising to 4.995.

As shown in Fig. 3A, initial phenol concentrations significantly impacted the growth rates and biomass accumulation of the mixed bacterial strains. Compared to 800 mg/L phenol, the growth rate at 1000 mg/L phenol was delayed by 6 h, with a 16.69% reduction in biomass. At 1200 mg/L phenol, biomass accumulation was further delayed by 12 h, with a substantial decrease of 25.80% compared to the biomass at 800 mg/L phenol. As the experimental results revealed that the phenol concentration significantly inhibited the biomass growth of mixed bacterial strains during fermentation, with the inhibitory effect intensifying as phenol concentration rises49.

As shown in Fig. 3B, the phenol degradation rates of the mixed strains varied significantly depending on the initial phenol concentration. At an initial concentration of 800 mg/L, phenol was completely degraded within 42 h. At 1000 mg/L, the degradation rate reached 81.04% within the same timeframe. However, when the initial concentration was increased to 1200 mg/L, the degradation rate dropped to only 40.22% within 42 h. These results indicated that higher phenol concentrations inhibit the metabolic activity of the halophilic strains, thereby reducing phenol degradation efficiency8.

The effect of mixed strains on phenol removal in high-salinity soil

The contaminated soil was prepared with 5% (w/v) NaCl and 300 mg/kg phenol, adjusted to a moisture content of 30% and pH 7.0. These contaminated soil samples were then inoculated with a mixture of bacterial strains PT-11 and PT-20. Soil samples were collected at regular intervals from both the blank control and experimental groups to determine the residual phenol content. A two-sample t-test was used for statistical analysis to compare the phenol content between the two groups at the end of the cultivation period. A p-value of 0.03 was obtained, indicating that the difference between the two groups was statistically significant. The results were shown in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 4, the phenol content in both the blank control and experimental groups decreased significantly over the cultivation period. In the experimental group with mixed bacterial strains, the phenol content decreased rapidly within 48 h, with a residual amount of just 22.5 mg/kg and achieving a degradation rate of 5.78 mg/kg/h. Complete phenol degradation was achieved within 72 h. In contrast, the blank control group without adding bacterial strains retained 24% residual phenol (70.6 mg/kg) after 72 h. The significant phenol reduction in the blank control group, despite the absence of added phenol-degrading bacteria, could be attributed to two primary factors. First, the saline soil samples were cultured in an open container at 30 °C, which facilitated the volatilization of phenol50. Second, the saline soil contained indigenous microorganisms which contributed to phenol degradation51. Compared to the blank control group, the experimental group exhibited a significantly higher phenol degradation rate, indicating that the mixed strains with PT-11 and PT-20 effectively remediate phenol-contaminated saline soil. In previous studies, researchers have explored the use of phenol-degrading strains for soil bio-remediation. Liu et al.52 employed the strain Acinetobacter radioresistens APH1 to treat soil contaminated with 450 mg/L phenol, achieving a removal rate of 99.03% within 3 d, with a degradation rate of 148.5 mg/kg/d. Chen et al.53 used Burkholderia sp. XTB-5 to treat soil containing 250 mg/kg phenol, achieving a 90% removal rate after 8 d at a degradation rate of 37.5 mg/kg/day. Wang et al.54 applied Pseudomonas aeruginosa SZH16 to soil contaminated with 100 mg/kg phenol, achieving an 85% removal rate after 15 d, with a degradation rate of 5.7 mg/kg/d.

Analysis of soil microbial diversity

Annotation and evaluation of saline soil microorganisms

Illumina MiSeq PE300 sequencing was performed on the extracted DNA from saline soil, generating a total of 904,111 sequences with an average length of 424 bp. The number of effective sequences for the blank control group (CK) and experimental group (PT) samples is shown in Table S1. Taxonomic annotation of the amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) was performed using the Silva 138/16S_bacteria database, and the abundance of each annotated ASV was quantified for each sample. The taxonomic annotation results revealed that the bacterial communities were classified into 17 phyla, 43 classes, 103 orders, 51 families, 232 genera, 323 species, and a total of 865 ASVs.

Analysis of soil microbial community diversity during microbial bio-remediation

Alpha diversity primarily reflects species richness and overall diversity within microbial communities55. Higher values of the Chao1 and Ace indices, a higher Shannon index, and a lower Simpson index collectively indicate greater microbial diversity in the samples56. The comparison of microbial richness at the genus level between the blank control group and experimental groups was shown in Table 3. In the blank control group, the Chao1, Ace, and Shannon indices were significantly higher than those in the experimental groups, while the Simpson index was significantly lower. These results suggest that the soil microbial community in the control group was richer and more diverse than that in the experimental groups. Additionally, no significant differences in microbial richness and diversity were observed across different fermentation times in the experimental groups, indicating that bacterial richness and diversity remained relatively stable throughout the fermentation period. The coverage index values for all samples exceeded 0.99, confirming a high probability of detecting sequences in the samples and suggesting comprehensive sampling coverage.

To intuitively assess the similarity of community structure among different samples, principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was used to compare microbial communities57. PCoA reduced dimensionality based on the selected distance matrix to identify main components influencing community composition differences, with shorter distances between samples indicating greater similarity in community structure58. The results were shown in the Fig. 5. The first principal coordinate accounted for 46.29% of the community variation, while the second principal coordinate accounted for 21.8%. The cumulative contribution rate of the two principal coordinates was 68.09%, which was greater than 50%, indicating that the coordinate axis showed a good overall explanatory power for bacterial community structure59. Samples from the experimental and blank control groups were distinctly separated at different sampling times, indicating that the addition of phenol and the mixed bacterial strains significantly altered community structure. Moreover, as extension of processing time, the differences between the experimental and blank control groups gradually diminished, with samples from both groups clustering more closely together at 72 h.

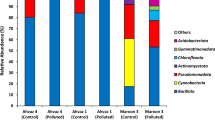

Analysis of species components during microbial bio-remediation

The presence of phenol showed a significant impact on the community composition of microorganisms in soil. With extension of processing time, microorganisms with phenol tolerance and degradation capabilities were relatively more likely to survive60. As shown in Fig. 6, the Venn diagram based on genus-level analysis revealed that all samples shared 25 common genera. Except for the blank control group sample at 0 h, the number of unique genera in the remaining samples was lower than the number of overlapping genera. Additionally, the community Circos diagram showed that the top-ranked genera were present in all samples but with varying abundances. As depicted in Fig. 7A, the genus-level community composition abundance map indicated that in the control group, the genera such as Baccilus, Clostridiisalibacter, Micrococcaceae, Chungangia, and Oceanobacillus exhibited higher abundances. This suggested these genera showed strong adaptability to phenol-contaminated environments, likely due to their inherent metabolic capabilities for phenol degradation or tolerance mechanisms61. Notably, the abundance of Oceanobacillus increased significantly with extension of processing time. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the phenol-degrading abilities of certain Oceanobacillus strains, which are known for their robustness in saline and contaminated environments62.

In the experimental group inoculated with the mixed strains, the abundance of the genus Oceanobacillus initially peaked at 95.59% at 0 h, then slightly decreased to 94% at 24 h. With extension of processing time, its abundance dropped significantly to 21.15% by 72 h. Meanwhile, the abundance of the genus Bacillus increased gradually, rising from an initial 1.14–42.33%, becoming the predominant genus. Additionally, the community heatmap further revealed that by 72 h (Fig. 7B), the experimental and blank control groups clustered together, with differences in community composition diminishing and the composition and abundance of dominant genera becoming increasingly similar. The introduction of exogenous microbial agents profoundly altered the soil microbial community structure8. Initially, the abundance of Oceanobacillus peaked, due to the inoculation of the mixed strains. However, with extension of processing time, phenol content decreased, the microbial community composition tended to diversify and eventually resembled the structure of the microbial community in blank control group63. This observation underscores that the composition of microbial community structure in the environment is shaped by long-term natural evolution, and the addition of exogenous microbial agents can only induce short-term changes in community composition64,65. Therefore, soil remediation through the addition of microbial agents, which alters soil community structure, is a long-term acclimatization process.

Conclusion

The genomic analysis of strains PT-11 and PT-20 offers key insights into their phenol degradation capabilities and their potential for bio-remediating saline soils. Strain PT-11, with its strong ortho pathway, and strain PT-20, which mainly uses the meta pathway, both show great potential for treating environments contaminated with phenol, especially in highly saline conditions. The mixed culture of PT-11 and PT-20 demonstrated efficient phenol degradation in saline soil, highlighting their potential for industrial waste treatment. The addition of the mixed strains significantly altered the soil microbial diversity, with the abundance of certain genera, such as Oceanobacillus, increasing initially and then stabilizing over time. This suggests that the introduction of exogenous microbial agents can induce short-term changes in the soil microbial community. Overall, the findings of this study support the use of microbial remediation as a sustainable and effective approach for treating phenol-contaminated soil, particularly in high-salinity environments.

In future research, the potential application of mixed bacterial strains in the coexistence of phenol and other pollutants will be explored, and the interaction mechanisms between various pollutants will be explored in depth to achieve effective treatment of multiple pollutants. Additionally, it is necessary to expand the scale of microbial remediation methods. This could be achieved by developing efficient technologies for cultivating and delivering bacterial strains to contaminated sites, as well as by evaluating the economic feasibility and technical challenges associated with scaling up from small-scale laboratory experiments to full-scale practical applications. Furthermore, it is crucial to implement a long-term monitoring plan for microbial remediation of contaminated soil. This plan aims to evaluate the actual efficacy of mixed bacterial strains in soil remediation processes and assess their long-term effects on soil microbial communities. Such monitoring is fundamental to revealing the ecological impacts of introducing external microbial agents and is critical for guaranteeing the sustained health and stability of soil ecosystems. Finally, by delving into these key future research directions, the study aims to enhance the practicality and sustainability of microbial remediation strategies for phenol-contaminated soil, thereby providing more reliable and effective solutions for environmental pollution control.

Data availability

The sequence data in this study has been deposited in the NCBI database under the accession number MTBQ00000000 for PT-11 and LQNFO00000000 for PT-20. All the other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alshabib, M. & Onaizi, S. A. A review on phenolic wastewater remediation using homogeneous and heterogeneous enzymatic processes: Current status and potential challenges. Sep. Purif. Technol. 219, 186–207 (2019).

Ahmaruzzaman, M. et al. Phenolic compounds in water: From toxicity and source to sustainable solutions-An integrated review of removal methods, advanced technologies, cost analysis, and future prospects. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12(3), 12964 (2024).

Zeng, X. et al. Ecological risk of phenol on typical biota of the northern Chinese river from an integrated probability perspective: The Hun River as an example. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195(12), 1512 (2023).

Raza, W. et al. Removal of phenolic compounds from industrial waste water based on membrane-based technologies. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 71, 1–18 (2019).

Khatri, I., Singh, S. & Garg, A. Performance of electro-Fenton process for phenol removal using iron electrodes and activated carbon. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6(6), 7368–7376 (2018).

Busca, G. et al. Technologies for the removal of phenol from fluid streams: A short review of recent developments. J. Hazard. Mater. 160(2–3), 265–288 (2008).

Annamalai, S. et al. Remediation of phenol contaminated soil using persulfate activated by ball-milled colloidal activated carbon. J. Environ. Manage. 310, 114709 (2022).

Zhao, W. et al. Development of a microbiome for phenolic metabolism based on a domestication approach from lab to industrial application. Commun. Biol. 7, 1716 (2024).

Sun, S. et al. Competitive mechanism of salt-tolerance/degradation-performance of organic pollutant in bacteria: Na+/H+ antiporters contribute to salt-stress resistance but impact phenol degradation. Water Res. 255, 121448 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Phenol degradation at high salinity by a resuscitated strain Pseudomonas sp. SAS26: Kinetics and pathway. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11(4), 10182 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Isolation of Bacillus paralichenifromis BL-1 and its potential application in producing bioflocculants using phenol saline wastewater. Microbiol. Res. 16(1), 23 (2025).

Deng, T., Wang, H. & Yang, K. Phenol biodegradation by isolated Citrobacter strain under hypersaline conditions. Water Sci. Technol. 77(2), 504–510 (2018).

Bonfá, M. R. L. et al. Phenol degradation by halophilic bacteria isolated from hypersaline environments. Biodegradation 24(5), 699–709 (2013).

Jiang, Y. et al. Phenol degradation by halophilic fungal isolate JS4 and evaluation of its tolerance of heavy metals. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 100(4), 1883–1890 (2016).

Jiang, Y. et al. Characteristics of phenol degradation in saline conditions of a halophilic strain JS3 isolated from industrial activated sludge. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 99(1–2), 230–234 (2015).

Haddadi, A. & Shavandi, M. Biodegradation of phenol in hypersaline conditions by Halomonas sp. strain PH2–2 isolated from saline soil. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 85, 29–34 (2013).

Zhang, C. et al. Dual metabolic pathways co-determine the efficient aerobic biodegradation of phenol in Cupriavidus nantongensis X14. J. Hazard. Mater. 460, 132424 (2023).

Agarry, S. E. & Solomon, B. O. Kinetics of batch microbial degradation of phenols by indigenous Pseudomonas fluorescence. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 5(2), 223–232 (2008).

Tuah, P. M., Rashid, N. A. A. & Salleh, M. M. Degradation pathway of phenol through ortho-cleavage by Candida tropicalis RETL-Cr1. Borneo Sci. 24, 432–567 (2009).

Zhou, W. et al. Phenol degradation by Sulfobacillus acidophilus TPY via the meta-pathway. Microbiol. Res. 190, 37–45 (2016).

Tawfeeq, H. R., Al-Jubori, S. S. & Mussa, A. H. Purification and characterization of catechol 1,2-dioxygenase (EC 1.13.11.1; catechol-oxygen 1, 2-oxidoreductase; C12O) using the local isolate of phenol-degrading Pseudomonas putida. Folia Microbiol. 69(3), 579–593 (2024).

Vasudeva, G. et al. Bioremediation of catecholic pollutants with novel oxygen-insensitive catechol 2,3-dioxygenase and its potential in biomonitoring of catechol in wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 367, 125613 (2025).

Long, X. et al. Oceanobacillus damuensis sp. nov. and Oceanobacillus rekensis sp. nov., isolated from saline alkali soil samples. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 108(3), 731–739 (2015).

Li, W. J. et al. Georgenia ruanii sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from forest soil in Yunnan (China), and emended description of the genus Georgenia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57(7), 1424–1428 (2007).

Luo, R. et al. SOAPdenovo2: An empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience 1, 18 (2012).

Delcher, A. et al. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 23, 673–679 (2007).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucl. Acids Res. 53, 672–677 (2025).

Tatusov, R. et al. The COG database: A tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucl. Acids Res. 28, 33–36 (2000).

Tanja, M. et al. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27(21), 2957–2963 (2011).

Chen, S. et al. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34(17), 884–890 (2018).

Robert, C. UPARSE: Highly accurate ASV sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 10(10), 996–998 (2013).

Wang, Q. et al. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73(16), 5261–5267 (2007).

Douglas, G. et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 685–688 (2020).

Han, C. et al. Majorbio cloud 2024: Update single-cell and multiomics workflows. Imeta 3(4), e217 (2024).

Schloss, P. et al. Introducing mothur: Open-Source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75(23), 7537–7541 (2009).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

Barberan, A. et al. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. 6, 343–351 (2012).

Griffiths, D. B. et al. Comparative genomics of the highly halophilic Haloferacaceae. Sci. Rep. 14, 27025 (2024).

Bustos, A. Y. et al. Recent advances in the understanding of stress resistance mechanisms in probiotics: Relevance for the design of functional food systems. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins 17, 138–158 (2025).

Boraston, A. B. et al. Carbohydrate-binding modules: Fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem. J. 382(3), 769–781 (2004).

Yu, Z. et al. The CAZyme family regulates the changes in soil organic carbon composition during vegetation restoration in the Mu Us desert. Geoderma 452, 117109 (2024).

Nešvera, J., Rucká, L. & Pátek, M. Catabolism of phenol and its derivatives in bacteria: Genes, their regulation, and use in the biodegradation of toxic pollutants. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 93, 107–160 (2015).

Setlhare, B. et al. Phenol hydroxylase from Pseudomonas sp. KZNSA: Purification, characterization and prediction of three-dimensional structure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 146, 1000–1008 (2020).

Shebl, S. et al. Aerobic phenol degradation using native bacterial consortium via ortho-and meta-cleavage pathways. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1400033 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Expression and characterization of catechol 1,2-dioxygenase from Oceanimonas marisflavi 102-Na3. Protein Expr. Purif. 188, 105964 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Biodegradation of phenol in saline or hypersaline environments by bacteria: A review. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 184, 109658 (2019).

Krastanov, A., Alexieva, Z. & Yemendzhiev, H. Microbial degradation of phenol and phenolic derivatives. Eng. Life Sci. 13, 76–87 (2013).

Anokhina, T. O. et al. Biodegradation of phenol at high initial concentration by Rhodococcus opacus 3D strain: Biochemical and genetic aspects. Microorganisms 13, 205 (2025).

Bonfá, M. R. L. et al. Phenol degradation by halophilic bacteria isolated from hypersaline environments. Biodegradation 24, 699–709 (2013).

Wang, Q., Bian, J. & Ruan, D. Volatilization of benzene on soil surface under different factors: Evaluation and modeling. Sustain. Environ. Res. 34, 18 (2024).

Sabri, I. et al. Novel insights into indigenous phenol-degrading bacteria from palm oil mill effluent and their potential mechanisms for efficient phenol degradation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 37, 103983 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Phenol biodegradation by Acinetobacter radioresistens APH1 and its application in soil bioremediation. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 104(1), 427–437 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Characterization of Burkholderia sp. XTB-5 for phenol degradation and plant growth promotion and its application in bioremediation of contaminated soil. Land Degrad. Dev. 28(3), 1091–1099 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. In situ degradation of phenol and promotion of plant growth in contaminated environments by a single Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain. J. Hazard. Mater. 192(1), 354–360 (2011).

Cassol, I., Ibañez, M. & Bustamante, J. P. Key features and guidelines for the application of microbial alpha diversity metrics. Sci. Rep. 15, 622 (2025).

Vance, E. D., Brookes, P. C. & Jenkinson, D. S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 19(6), 703–707 (1987).

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microb. 71(12), 8228–8235 (2005).

Shi, Y. et al. aPCoA: Covariate adjusted principal coordinates analysis. Bioinformatics 36(13), 4099–4101 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Microbial community composition and co-occurrence network analysis of the rhizosphere soil of the main constructive tree species in Helan Mountain of Northwest China. Sci. Rep. 14, 24557 (2024).

Huang, L. et al. The mechanism of survival and degradation of phenol by Acinetobacter pittii in an extremely acidic environment. Environ. Res. 260, 119596 (2024).

Long, X. et al. Glycine betaine enhances biodegradation of phenol in high saline environments by the halophilic strain Oceanobacillus sp. PT-20. RSC Adv. 9(50), 29205–29216 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Meta-analysis reveals the effects of microbial inoculants on the biomass and diversity of soil microbial communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1270–1284 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Composition and metabolism of microbial communities in soil pores. Nat. Commun. 15, 3578 (2024).

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (No. 2024GXNSFBA010351), and Guangxi University of Science and Technology Doctoral Fund (No. 20Z18).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. Tian and X. Long designed the experiments; J. Tian, Y. Qing, M. Zang and Y. Ma performed experiments; J. Tian and X. Long analyzed the data; J. Tian wrote the manuscript draft; X. Long and G. Liu reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, J., Qing, Y., Zang, M. et al. Genomic insights into phenol degradation by halophilic bacteria and their potential application in saline soil remediation. Sci Rep 15, 32740 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08348-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08348-w