Abstract

The growing demand for environmentally sustainable technologies has intensified research into high-frequency motors and transformers, where Fe-Si soft magnetic alloys play a crucial role due to their exceptional magnetic properties. However traditional manufacturing methods limit geometric freedom and degrade alloy performance capabilities, hindering the development of advanced applications. To overcome these issues, laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) offers a promising route by enabling complex shapes, yet mitigating eddy current losses remains challenging at elevated frequencies. As a preliminary study, this work investigates the effect of adjusting laser beam profiles (Gaussian versus ring) on the eddy current losses and magnetic properties of Fe-Si alloys produced by L-PBF. A microstructural analysis demonstrates that the ring beam produces a broader, shallower melt pool, fostering coarser grains and a pronounced < 100 > crystallographic texture along the build direction. These microstructural features significantly reduce the coercivity and core loss of the material, strongly highlighting their effectiveness in addressing the aforementioned challenges related to the eddy current. Additionally, the ring beam increased the build rate by approximately 108%, clearly illustrating enhanced productivity without compromising quality. This study confirms that modifying the laser beam profile effectively controls eddy current losses, enhancing the magnetic performance of Fe-Si soft magnetic alloys fabricated via additive manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global push towards environmental sustainability has intensified the demand for energy-efficient technologies across various sectors1. In the context of electric motors and power systems, this shift has driven significant advancements in high-efficiency components. Soft magnetic materials, known for their ability to be easily magnetized and demagnetized, play a decisive role in power generation and conversion for electronic devices2,3. These materials exhibit high saturation magnetization, electrical resistivity, and permeability, along with low core loss and coercivity, making them essential for energy conversion and efficiency in applications such as electric vehicles (EVs), motors, generators, and transformers3,4,5,6,7,8. Among these materials, Fe-Si (iron-silicon) alloys are the most widely used in electrical machines, such as motor cores, due to their notable magnetic properties, including high resistivity, permeability, magnetic saturation, and low energy loss. Although adding silicon can slightly reduce the magnetic saturation, its primary benefit is to increase the electrical resistivity, which effectively reduces the eddy current losses and improves the overall energy efficiency9. Consequently, these alloys exhibit low core loss and enhanced performance in motors and transformers3,4,5,6. In particular, electric motor components require lightweight designs and 3D-complex geometries to maximize efficiency and performance in modern applications10,11. However, meeting these demands remains a challenge with conventional processing routes, primarily continuous casting followed by rolling12, as well as powder metallurgy3. These methods often limit geometric flexibility and introduce mechanical stresses that degrade the magnetic performance of Fe-Si alloys13,14.

In this context, additive manufacturing (AM), particularly laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF), presents a promising alternative by enabling the fabrication of complex geometries with high precision while also reducing material waste15. L-PBF offers remarkable design flexibility, allowing the creation of intricate geometries and facilitating the development of advanced materials with unique properties and functionalities13,16,17. However, the traditional single-mode Gaussian beam profile, widely used in conventional L-PBF systems, is characterized by highly concentrated heat at the beam center18. This configuration leads to excessive spatter, soot, and defects in metal parts, particularly the formation of narrow and deep melt pools, which are susceptible to keyhole instability—a phenomenon that can cause defects such as porosity, gas entrapment, a lack of fusion, and irregular solidification structures19,20. These defects negatively affect the overall quality and functional properties of the fabricated parts. Additionally, the steep thermal gradients associated with Gaussian beam profiles result in rapid solidification, yielding grain refinement and an increasing grain boundary density21. In soft magnetic materials such as Fe-Si alloys, the high density of grain boundaries acts as pinning sites for magnetic domain walls, thus suppressing their movement22,23. This microstructural characteristic leads to increased coercivity and core losses, significantly diminishing the magnetic performance capabilities of Fe-Si alloys and limiting their applicability in advanced electromagnetic systems.

Addressing these challenges requires innovative strategies. In recent years, there has been increased interest in altering the energy distribution of the laser source by controlling the laser beam profiles, which has emerged as a promising approach. By tailoring the laser beam profile, it is possible to influence the melt pool dynamics, control the evolution of the microstructure, and reduce defect formation during the L-PBF process24,25. Recently, advanced beam-shaping techniques have been actively studied for their potential to enhance process stability and overall material performance outcomes. One such method is the adoption of ring-shaped (donut) laser beam profiles, which have garnered significant attention for modulating thermal gradients and reducing keyhole porosity26,27,28. Advanced laser systems, such as an nLight AFX laser, enable dynamic transitions between Gaussian and ring-shaped beam profiles, thereby providing enhanced process control. The benefits of laser beam shaping have been observed in several domains, including increased hatch spacings and scan speeds to enhance productivity26, reduced spatter and porosity for improved part density levels27, and improved melt pool stability to minimize defects28. Specifically, with the ring-shaped beam, the melt pool becomes more stable—leading to fewer keyhole defects, less spatter, and better overall part integrity. By redistributing the laser energy around a broader perimeter, this beam configuration mitigates the extreme temperature gradients typical of a Gaussian beam, thus minimizing soot formation and recoater crashes. Despite these advancements in beam shaping, there remains a significant knowledge gap regarding the extent to which these improvements translate into useful functional properties, particularly improved magnetic performance. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between beam shaping, microstructural evolution, and the resulting magnetic characteristics remains an active area of investigation.

This paper aims to investigate the effects of an adjustable laser beam profile, the Gaussian and ring beam, on the microstructure and magnetic properties of Fe-Si soft magnetic alloys fabricated using the L-PBF process. The findings are expected to provide valuable insights into optimizing additive manufacturing strategies to achieve tailored properties, broadening the applicability of L-PBF for functional materials, such as soft magnetic alloys and related materials.

Methods

Schematic of the custom-built L-PBF system. The image was created by the authors using Autodesk Inventor Professional 2024, Build 343 (Autodesk Inc., https://www.autodesk.com/products/inventor/).

The laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) system employed in this study was a retrofitted, self-developed machine equipped with an AFX-1000 variable beam profile laser (nLight Inc., USA), as illustrated in Fig. 1. The system features a cylindrical build platform (build volume: ϕ 150 mm × H 150 mm), housed within an argon-filled chamber measuring 810 mm × 460 mm × 320 mm. Powder spreading, or recoating, is performed in a linear manner using a rubber blade with an effective length of 155 mm. The AFX-1000 laser is capable of switching among seven distinct intensity profiles, ranging from a single-mode beam to an almost fully ring-shaped beam. This beam-shaping flexibility is achieved by redistributing the laser power between the central core (core energy) and the first fiber cladding layer (ring energy). The laser operates at a wavelength of 1070 nm, with a maximum power output of 500 W. Figure 2 depicts representative laser intensity profiles for two configurations: the Gaussian beam and the ring beam, highlighting different power distributions between the fiber core and the annular ring. The Gaussian beam corresponds to the conventional profile commonly used in L-PBF processes, whereas the ring beam approximates an annular distribution, with reduced central intensity and energy propagating from the surrounding ring.

The material used in this study was gas-atomized spherical Fe-4.5 wt.%Si powder with a median particle size (D50) of 26.5 μm, supplied by MK Co., Republic of Korea. The L-PBF process was carried out on a stainless steel substrate using a custom-built L-PBF machine. An argon atmosphere with an oxygen concentration maintained below 100 ppm was employed to prevent oxidation during fabrication. In this work, two types of specimens were fabricated: (1) cubic samples (10 × 10 × 10 mm³) for a microstructural analysis, and (2) toroidal samples (outer diameter 25 mm, inner diameter 15 mm, height 1 mm) aligned parallel to the build direction (BD) for a magnetic property evaluation. The L-PBF process was conducted using a laser power of 200 W, a scan speed of 1000 mm/s, an overlap ratio of 30%, and a layer thickness of 30 μm. A zigzag scanning pattern was employed for all specimens. For the cubic specimens, the scanning axis was fixed along the x-axis. In contrast, for the toroidal specimens, the scanning axis alternated between the x-axis and the y-axis in successive layers to promote isotropy and minimize residual stresses. Additionally, the scanning direction of each track was reversed by 180 degrees in alternating layers to reduce residual stresses further and achieve a more uniform microstructure.

To reveal the melt pool structure, the as-built specimens were subjected to a series of preparation steps. First, the specimens were ground using a 1 μm carbon abrasive, followed by two hours of mechanical polishing in a vibrating polisher (VibroMet 2, Buhler, Switzerland) with a 20 nm silica solution. The polished specimens were then etched with 1.5–3% nitric acid for one to two minutes. Microstructural observations were conducted by means of optical microscopy (OM, GX51, Olympus, Japan) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-+RA3, TESCAN, Czech Republic), with the devices equipped with electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), ensuring high-resolution visualization of the melt pool morphology. An EBSD analysis was also conducted using a scanning electron microscope operating at 20 kilovolts, with a step size of 5 microns, to investigate the detailed microstructural evolution during the L-PBF process, including the crystallographic orientation and grain characteristics. The magnetic properties of the toroidal specimens were evaluated using a BH tracer (SY-8219, Iwatsu, Japan) at a frequency of 50 Hz and a maximum magnetic flux density of 1 Tesla in order to assess the core loss and coercivity.

Results and discussion

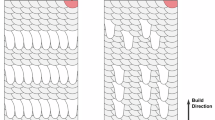

Figure 3 presents optical microscopy (OM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the melt pool cross-sections (XZ plane) of the as-built Fe-Si soft magnetic alloy parts. It was found that specimens fabricated using both the Gaussian and ring beam profile achieved a sound microstructure, without critical defects such as pores or cracks and with nearly full density, exceeding 99%, as shown in Figs. 3(a) and (b). The results reveal that the process window used in this study enables effective material consolidation with both beam profiles, potentially resulting in high-quality components with excellent structural integrity. Despite the small difference in the overall porosity, distinct differences in the melt pool structure were observed; these are attributable to the characteristics and behaviors of the different beam profiles.

Patel et al.29 identified a depth-to-width ratio of approximately 0.5 as a practical boundary between keyhole-mode and conduction-mode melting. When the ratio exceeds approx. 0.5, the melt pool is generally considered to be the keyhole mode, whereas lower values indicate the conduction mode. In Fig. 3(c), the Gaussian beam specimen exhibits a narrower, deeper melt pool with a half-width of 70.3 μm and a depth of 92.0 μm, resulting in a ratio of approximately 0.65, which places it in the keyhole mode29. This case is associated with potential defects such as keyhole porosity, gas entrapment, a lack of fusion, and irregular solidification structures due to unstable keyhole formation and collapse, which can degrade the mechanical properties and reduce the performance capabilities of the final components19,20. In contrast, Fig. 3(d) shows the ring beam specimen, indicating the formation of a broader, shallower melt pool with a half-width of 108.5 μm and a depth of 47.9 μm, resulting in a depth-to-width ratio of approximately 0.22, which corresponds to conduction-mode melting24,29. The more distributed heat input across a larger area provides more uniform heat dispersion and lower peak temperatures, leading to reduced thermal gradients and enabling increased hatch spacing without compromising the melt pool stability. As conduction-mode operation typically offers improved process stability and a lower risk of defects compared to the keyhole mode30, the ring beam profile thus fosters a more stable melt pool regime.

To investigate these observations further, a scanning electron microscope (SEM) was employed to characterize the cross-sectional microstructure of the melt pool. As illustrated in Fig. 3(e), the Gaussian beam specimen contains several small pore-like voids, which may arise from transient keyhole instability or the partial collapse of a mini-keyhole. To clarify their characteristics and spatial distribution, additional high-magnification SEM images were acquired. A representative higher-magnification SEM image is presented in the insert of Fig. 3(e). A quantitative analysis found that most pores are concentrated near the bottom of the melt pool, suggesting that localized mini-keyhole collapse occurs preferentially close to the beam axis. This observation is in good agreement with the “instant-bubble” mechanism and sporadic pores reported by Zhao et al.31 under near-threshold laser conditions. Wang et al.32 further showed—through a combination of simulations and experiments—that keyhole pores accumulate at the bottom of the laser-scanning track because the local liquid-velocity field and Bernoulli pressure prevent the bubbles from rising and pin them at the solidification front. Accordingly, no extensive porosity network or continuous vapor channel could be observed in the samples, indicating that the melt pool under the Gaussian beam remains in a transitional regime between the conduction and keyhole modes.

In contrast, Fig. 3(f) shows that the ring beam specimen exhibits a broader, shallower melt pool free of these voids, consistent with conduction-mode melting. A more uniform heat distribution and reduced thermal gradients help prevent abrupt keyhole collapses, diminishing the likelihood of keyhole-related defects. Overall, the SEM results indicate that while the Gaussian beam condition can occasionally produce localized pores indicative of partial keyhole activity, the ring beam promotes a more stable conduction-mode melting process.

The difference in the melt pool formation behavior between the two beam profiles has a significant effect on the productivity of the L-PBF process. To obtain a quantitative estimate of this effect, the build rates for both beam profiles were calculated based on the melt pool dimensions and process parameters. Figure 4 illustrates the scanning paths for the Gaussian and ring beams, along with the corresponding process parameters and calculated build rates. Specifically, at a scan speed of 1000 mm/s and with 30% overlap and a 30 μm layer thickness, the Gaussian beam exhibited a calculated build rate of 1.932 mm³/s, whereas the ring beam achieved a calculated build rate of 4.032 mm³/s. This corresponds to an approximate 108% increase in the build rate when using the ring beam compared to the Gaussian beam. The significant productivity enhancement is primarily attributed to the broader melt pool of the ring beam and its operation in conduction mode. By avoiding the instabilities and defects associated with the keyhole mode, the ring beam ensures greater process stability, allowing for an increase in the hatch spacing. The stable melt pool dynamics in the conduction mode, with low to negligible turbulence in the melt pool, can provide potential benefits such as reduced spatter, fewer defects such as porosity and cracks33, and minimal formation of undesirable intermetallic compounds due to limited metal mixing34.

Previous studies35,36,37 have reported the benefits of using a ring-shaped laser beam to stabilize the melt pool and enhance the surface quality when utilizing laser processing techniques. Specifically, Sun et al.37 demonstrated the impact of adjustable laser beams on the microstructure and mechanical performance outcomes of certain welding processes, highlighting how an adjustable ring-mode laser can modify cooling rates and improve the resultant grain structures. Other recent numerical and experimental investigations38,39,40 have also shed light on the mechanisms by which ring-shaped or spatially extended beams reduce peak temperatures, moderate thermal gradients, and promote conduction-mode melting. For instance, a power-ratio study by Sun et al.37 indicated that distributing energy between a core and ring beam can yield a more uniform thermal field and suppress keyhole tendencies, while Xiong et al.38 emphasized the role of an outward convection flow in creating a wider mushy zone and facilitating equiaxed grain growth. Moore et al.39 showed that ring and Bessel beams tend to form shallower melt pools and lower peak temperatures compared to Gaussian beams, enhancing both process stability and grain control. A recent modeling approach40 similarly revealed that ring-shaped energy distributions help mitigate excessive thermal gradients and steer the melt pool toward the conduction mode—much like the behavior observed in this study. These trends are also reflected in our results, where similar effects of beam profiles on the microstructural evolution during L-PBF were observed. Such improvements in the melt pool behavior are expected to influence the microstructure and, consequently, the magnetic properties of the fabricated Fe-Si soft magnetic alloys.

As shown in Fig. 5(a), the EBSD analysis provided detailed insights into the grain structure and orientation on both the XY and XZ planes for samples produced using the Gaussian and ring laser beam profiles. On the XY plane, the Gaussian beam resulted in a fine equiaxed grain structure, typically observed when using rapid solidification processes. High cooling rates from the concentrated heat input generated numerous nucleation sites, resulting in smaller grain sizes, consistent with the grain refinement effect observed in the keyhole mode41. In contrast, the ring beam promoted the formation of coarse grains due to the broader heat distribution and slower cooling rates. The reduced thermal gradients allowed for extended grain growth during solidification, leading to grain coarsening. This coarser grain structure is beneficial for magnetic applications, as it reduces the density of grain boundaries that can restrict the movement of magnetic domain walls42.

On the XZ plane, the printed samples prepared using the ring beam exhibited elongated grains aligned along the build direction (BD), resulting in the formation of a strong < 100>//BD texture. Although columnar grains were observed to grow along the BD for both beam profiles, significant differences were found in the average grain size and texture intensity (Fig. 5(b)). Specifically, the ring beam specimen exhibited an average grain diameter and height of 69 μm and 341 μm, respectively, approximately 1.5 times larger than those measured for the Gaussian beam specimen (45 μm and 200 μm). Meanwhile, the < 100>//BD texture intensity was markedly enhanced, increasing from 9.6 under the Gaussian beam to 22.0 under the ring beam, reflecting the strong influence of beam topology on preferred grain orientation. These observations can be attributed to differences in the melt pool morphology; the broader and shallower melt pool associated with the ring beam facilitates more uniform heat flow along the BD, promoting directional solidification and the growth of coarser, more textured grains compared to the Gaussian beam. This behavior is consistent with previous findings43, which demonstrated that the application of a ring-shaped laser beam significantly influenced crystallographic texture evolution by promoting more uniform thermal gradients and directional solidification. Specifically, a linear correlation was found between the curvature radius at the bottom of the melt pool and the resulting texture index, particularly under ring beam conditions. This suggests that the observed increase in < 100>//BD texture intensity and grain size in our Fe-Si samples processed with the ring beam may have similarly resulted from the mitigation of the thermal gradients and a flatter melt pool geometry.

These microstructural differences significantly affected the magnetic properties of the printed samples. Figure 5(c) presents the magnetic hysteresis behavior of specimens fabricated using Gaussian and ring beam profiles. Notably, the ring beam specimen achieved magnetic flux density of 1 T under a lower applied field compared to the Gaussian counterpart. In addition, the coercivity, indicated by the x-intercept, was significantly reduced in the ring beam specimen, suggesting improved soft magnetic performance. Figure 5(d) presents comprehensive overview of the specific coercivity and core loss values for both beam profile. The core loss and coercivity for the ring beam specimens were 2.75 W/kg and 159 A/m, respectively, indicating improvements over the Gaussian beam specimen, for which the corresponding values were 3.74 W/kg and 190 A/m. These enhancements can be mainly attributed to a reduction in the grain boundaries, which suppresses movement of the magnetic domain. Additionally, the increased texture strength of the < 100>//BD orientation is known to exhibit superior magnetic properties44. Nevertheless, the magnetic performance of the ring beam specimen did not match that of commercial-grade steel. This discrepancy is likely due to the presence of numerous low-angle grain boundaries, as indicated by color variations within individual grains in the IPF maps. These boundaries promote the formation of finer magnetic domains and suppress domain movement, ultimately degrading the magnetic properties45. Therefore, further post-processing steps, such as a heat treatment, may be required to eliminate these boundaries and improve the magnetic performance further.

The results demonstrated in this study clearly show that the ring beam profile not only improves productivity but also enables in-situ manipulation of the microstructure and magnetic properties of Fe-Si soft magnetic alloys fabricated via L-PBF. Traditionally, control over microstructure and magnetic properties has relied on adjusting process parameters or applying post-processing treatments. However, modifying the laser beam profile allows for a more direct and efficient approach to tailoring these properties. By manipulating the solidification process through beam shaping, desired material characteristics can be achieved without the need for additional processing steps. This represents a significant advancement in the additive manufacturing of magnetic materials, providing a pathway for the tailored fabrication of components to meet specific application requirements.

This work represents a preliminary step toward verifying the feasibility of controlling the microstructural and magnetic properties of Fe-Si soft magnetic alloys through laser beam profile adjustments. Building on these promising findings, future studies will aim to expand the process–structure–property–performance (PSPP) framework by exploring advanced beam profiles, such as ring and hybrid beams, alongside refined scanning strategies. To be specific, previous studies have demonstrated that laser energy input and scanning parameters significantly influence melt pool characteristics and the resulting microstructures, including the grain morphology and crystallographic textures in Fe-Si alloys46,47. This foundational understanding highlights the potential for tailoring properties further through precise control of beam shape and scan strategy47,48.

To this end, establishing a correlation between real-time melt pool behavior, microstructural evolution, and magnetic response will be critical for developing predictive models that support the systematic optimization of processing conditions for tailored microstructures and enhanced magnetic properties in soft magnetic materials. In this context, advanced multi-physics simulations can provide valuable insights into the interrelated phenomena of melt pool dynamics, thermal gradients, solidification rates, and texture development under various processing conditions46,47,49. Such modeling efforts, when closely integrated with experimental validation, can offer a more comprehensive understanding of these complex interdependencies48. Moreover, post-processing treatments such as stress-relief annealing or controlled heat treatments should be systematically investigated under varying as-built conditions determined by beam mode, in order to mitigate residual stresses and suppress the formation of detrimental low-angle grain boundaries. Extensive research has emphasized the importance of annealing in relieving residual stresses, promoting grain growth, and enhancing magnetic performance in additively manufactured soft magnetic materials, often while preserving beneficial crystallographic textures48,49,50. Tailoring such heat treatments to the beam-profile-dependent microstructure is essential for realizing optimal magnetic functionality47.

Together, these research directions will provide the necessary foundation for establishing robust, beam-profile-based design strategies for next-generation soft magnetic components fabricated through laser-based additive manufacturing.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of controlling both microstructural and magnetic properties in Fe-Si soft magnetic alloys fabricated by L-PBF through adjustments to laser beam profiles, specifically comparing Gaussian and ring beam configurations. The key findings are summarized as below.

-

The ring beam consistently produced a broader and shallower melt pool indicative of the conduction mode melting, whereas the Gaussian beam generated a narrower and deeper melt pool, typically associated with the keyhole mode behavior.

-

A microstructural analysis revealed that the ring beam promoted coarser grain growth and a more pronounced < 100>//BD crystallographic texture. Additionally, pore-like voids were observed near the melt pool bottom in Gaussian beam specimens, which are likely the result of the localized mini-keyhole collapse phenomenon.

-

These distinct microstructural features directly contributed to enhanced magnetic performance; the ring beam reduced the coercivity from 190 A/m to 159 A/m and significantly lowered the core loss from 3.74 W/kg to 2.75 W/kg (at 50 Hz and 1 T) compared to the Gaussian beam.

-

Beyond the magnetic enhancements, the ring beam improved build productivity by approximately 108% compared to the Gaussian beam, primarily due to its ability to accommodate wider hatch spacing distances without compromising part integrity, thereby reducing the number of fusion lines per built surface.

These findings collectively highlight the potential of adjustable laser beam profile engineering as a powerful approach for in-situ control of microstructures and functional properties in additively manufactured materials, with promising applicability to next-generation high performance electrical machines.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lamichhane, T. N. et al. Additive manufacturing of soft magnets for electrical machines – a review. Mater. Today Phys. 15, 100255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2020.100255 (2020).

Dietrich, D. W. Magnetically soft materials. In: Properties and Selection: Nonferrous Alloys and Special-Purpose Materials (ed. ASM Handbook Committee), 761–781. ASM International (1990).

Sun, K. et al. Direct energy deposition applied to soft magnetic material additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 84, 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.10.004 (2022).

Stornelli, G., Faba, A., Di Schino, A. & Ceschini, L. Properties of additively manufactured electric steel powder cores with increased Si content. Materials 14, 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14061489 (2021).

Shokrollahi, H. & Janghorban, K. Soft magnetic composite materials (SMCs). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 189, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.02.034 (2007).

Calvillo, P. R. et al. Plane strain compression of high silicon steel. Mater. Sci. Technol. 22, 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1179/174328406X114207 (2006).

Żukowska, M., Rad, M. A. & Górski, F. Additive manufacturing of 3D anatomical models — review of processes, materials and applications. Materials 16, 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16020880 (2023).

Lehmhus, D. et al. Customized smartness: a survey on links between additive manufacturing and sensor integration. Procedia Technol. 26, 284–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2016.08.038 (2016).

Choi, Y. S. et al. A study on the optimization of metalloid contents of Fe–Si–B–C based amorphous soft magnetic materials using artificial intelligence method. Arch. Metall. Mater. 67, 1459–1463. https://doi.org/10.24425/amm.2022.141074 (2022).

Paul, R. et al. New production techniques for electric motors in high performance lightweight applications. Proc. IEEE EDPC. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1109/EDPC51184.2020.9388183 (2020).

Nikita, G. B. et al. Modeling and simulation of electric motors using lightweight materials. Energies 15, 5183. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15145183 (2022).

Ouyang, G., Chen, X., Liang, Y., Macziewski, C. & Cui, J. Review of Fe-6.5 wt%si high silicon steel — a promising soft magnetic material for sub-kHz application. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 481, 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2019.02.089 (2019).

Zanni, M. et al. Relationship between microstructure, mechanical and magnetic properties of pure iron produced by laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) in the as-built and stress-relieved conditions. Prog Addit. Manuf. 7, 505–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-021-00219-8 (2022).

ASM International. Blanking and piercing of electrical steel sheet. In: Metalworking: Sheet Forming, 171–176. ASM International. (2006).

Stornelli, G. et al. Development of fesi steel with increased Si content by laser powder bed fusion technology for ferromagnetic cores application: microstructure and properties. MRS Adv. 8, 1845–1853. https://doi.org/10.1557/s43580-023-00646-7 (2023).

Herzog, D., Seyda, V., Wycisk, E. & Emmelmann, C. Additive manufacturing of metals. Acta Mater. 117, 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2016.07.019 (2016).

Hebert, R. J. Viewpoint: metallurgical aspects of powder bed metal additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Sci. 51, 1165–1175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-015-9479-x (2016).

Metelkova, J. et al. On the influence of laser defocusing in selective laser melting of 316L. Addit. Manuf. 23, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.08.006 (2018).

King, W. E. et al. Observation of keyhole-mode laser melting in laser powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 214 (12), 2915–2925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2014.06.005 (2014).

Li, Q. et al. Identifying the keyhole stability and pore formation mechanisms in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 321, 118153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2023.118153 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Additive manufactured high entropy alloys: a review of the microstructure and properties. Mater. Des. 220, 110875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.110875 (2022).

Tan, X. et al. Enhanced DC and AC soft magnetic properties of Fe–Co–Ni–Al–Si high-entropy alloys via texture and iron segregation. Metals 14, 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/met14101113 (2024).

Rodriguez-Vargas, B. R. et al. Recent advances in additive manufacturing of soft magnetic materials: a review. Materials 16, 5610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16165610 (2023).

Ebrahimi, A. et al. Revealing the effects of laser beam shaping on melt pool behaviour in conduction-mode laser melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 27, 3955–3967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.11.046 (2023).

Wischeropp, T. M., Tarhini, H. & Emmelmann, C. Influence of laser beam profile on the selective laser melting process of AlSi10Mg. J. Laser Appl. 32, 022059. https://doi.org/10.2351/7.0000100 (2020).

Grünewald, J. et al. Influence of ring-shaped beam profiles on process stability and productivity in laser-based powder bed fusion of AISI 316L. Metals 11, 1989. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11121989 (2021).

Mohammadpour, M. et al. Adjustable ring mode and single beam fiber lasers: a performance comparison. Manuf. Lett. 25, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mfglet.2020.07.003 (2020).

Holla, V. et al. Laser beam shape optimization in powder bed fusion of metals. Addit. Manuf. 72, 103609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103609 (2023).

Patel, S. & Vlasea, M. Melting modes in laser powder bed fusion. Materialia 9, 100591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtla.2020.100591 (2020).

Kaplan, A. F. H. & Powell, J. Spatter in laser welding. J. Laser Appl. 23 (3), 032005. https://doi.org/10.2351/1.3597830 (2011).

Zhao, C. et al. Critical instability at moving keyhole tip generates porosity in laser melting. Science 370, 1080–1086. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd1587 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Mechanism of keyhole pore formation in metal additive manufacturing. Npj Comput. Mater. 8, 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00699-6 (2022).

Gunenthiram, V. et al. Analysis of laser–melt pool–powder bed interaction during the selective laser melting of a stainless steel. J. Laser Appl. 30 (3), 032601. https://doi.org/10.2351/1.5040624 (2018).

Cao, L. et al. Investigation of intermetallics formation and joint performance of laser welded Ni to al. Appl. Sci. 13, 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031356 (2023).

Rasch, M. et al. Shaped laser beam profiles for heat conduction welding of aluminium–copper alloys. Opt. Lasers Eng. 115, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2018.11.025 (2019).

Duocastella, M. & Arnold, C. B. Bessel and annular beams for materials processing. Laser Photon Rev. 6, 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201100031 (2012).

Sun, T. et al. The impact of adjustable-ring-mode (ARM) laser beam on the microstructure and mechanical performance in remote laser welding of high-strength aluminium alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 21, 2247–2261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.10.055 (2022).

Xiong, F., Gan, Z., Chen, J. & Lian, Y. Evaluate the effect of melt pool convection on grain structure of IN625 in laser melting process using experimentally validated process-structure modeling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 303, 117538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2022.117538 (2022).

Moore, R. et al. Microstructure-based modeling of laser beam shaping during additive manufacturing. JOM 76, 1726–1736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-023-06363-8 (2024).

Choi, S. H., Kim, J. H. & Choi, H. W. Ring beam modulation-assisted laser welding on dissimilar materials for automotive battery. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 9, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9020028 (2025).

Zhang, D. et al. Grain refinement of alloys in fusion-based additive manufacturing processes. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 51, 4341–4359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-020-05880-4 (2020).

Shiozaki, M. & Kurosaki, Y. The effects of grain size on the magnetic properties of non-oriented electrical steel sheets. J. Mater. Eng. 11 (1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02833749 (1989).

Pérez-Ruiz, J. D. et al. Laser beam shaping facilitates tailoring the mechanical properties of IN718 during powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 328, 118393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2024.118393 (2024).

Sidor, J. J. et al. Through process texture evolution and magnetic properties of high Si non-oriented electrical steels. Mater. Charact. 71, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2012.06.005 (2012).

Lindquist, A. K. et al. Domain wall pinning and dislocations: investigating magnetite deformed under conditions analogous to nature using transmission electron microscopy. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 120 (3), 1415–1430. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011335 (2015).

Garibaldi, M., Ashcroft, I., Simonelli, M. & Hague, R. Metallurgy of high-silicon steel parts produced using selective laser melting. Acta Mater. 110, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2016.03.037 (2016).

Meng, F. et al. The selection of scanning strategy and annealing schedule for the optimization of texture and magnetic properties of Fe-3.5 wt%si alloy parts fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 97, 104614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2024.104614 (2025).

Shen, X. et al. Evaluation of microstructure, mechanical and magnetic properties of laser powder bed fused Fe-Si alloy for 3D magnetic flux motor application. Mater. Des. 234, 112343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112343 (2023).

Garibaldi, M., Ashcroft, I., Hillier, N., Harmon, S. A. C. & Hague, R. Relationship between laser energy input, microstructures and magnetic properties of selective laser melted Fe-6.9 wt% Si soft magnets. Mater. Charact. 143, 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2018.01.016 (2018).

Garibaldi, M., Ashcroft, I., Lemke, J. N., Simonelli, M. & Hague, R. Effect of annealing on the microstructure and magnetic properties of soft magnetic Fe-Si produced via laser additive manufacturing. Scripta Mater. 142, 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2017.08.042 (2018).

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Research Program funded by the Korea Institute of Machinery and Materials (KIMM) (No. NK255C), and the Technology Innovation Program funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE, Korea) (No. RS-2024-00441774).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.K., J.P.C; Methodology: Y.K., H.L; Software: Y.K. H.L; Validation: Y.K., H.L; Formal Analysis: Y.K, H.L, J.P.C; Investigation: Y.K, J.P.C; Resources: T.H., J.K; Data Curation: Y.K, H.L; Writing—Original Draft: Y.K., J.P.C.; Writing—Review and Editing: J.P.C.; Visualization: H.L, J.K.; Supervision: J.P.C.; Project Administration: T.H., J.P.C.; Funding Acquisition: T.H., J.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Lee, H., Ha, T. et al. Effects of laser beam profiles on the microstructure and magnetic properties of L-PBF soft magnetic alloys. Sci Rep 15, 22336 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08385-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08385-5