Abstract

Collar rot, caused by Agroathelia rolfsii, is a devastating soil-borne disease affecting Cicer arietinum L (chickpea) leading to significant agricultural productivity losses. This study investigates the antifungal potential of the cyanobacterium Desertifilum dzianense, isolated from monument stone crusts in Odisha, India, as a natural biocontrol agent against A. rolfsii. Phytochemical screening of crude extracts revealed the presence of bioactive secondary metabolites, including alkaloids and phenolic compounds. The methanolic extract demonstrated the highest antifungal activity, with significant inhibition of A. rolfsii growth in agar well diffusion assays. Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) analysis identified active fractions, which were further characterized by UV-Vis and FTIR spectroscopy, confirming the presence of alkaloids as the primary antifungal compounds. The bioautography assay validated the antifungal efficacy of the purified fractions. These results support that D. dzianense have strong antifungal potency and can be used as eco-friendly biocontrol agent to control collar rot in chickpea cultivation. However, field trials and cytotoxicity assessment can reflect the safety and efficacy of this biocontrol system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), one of the most valuable leguminous pulse crops worldwide, is a key source of protein, carbohydrates, lipids, and essential vitamins and minerals. It plays a crucial role in soil fertility through nitrogen fixation and sustains agricultural systems, particularly in regions such as South Asia, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. Despite its importance, chickpea cultivation faces numerous challenges, including fungal diseases that significantly threaten crop yield and quality. Among these, collar rot caused by Agroathelia rolfsii (anamorph: Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc.) is particularly devastating, leading to seedling mortality rates as high as 95% under favourable conditions. This disease not only reduces seed yield and weight but can result in complete crop failure under severe infestations1,2.

The management of A. rolfsii remains a significant challenge due to its high pathogenic variability, wide host range, and the long-term survival of its sclerotia in soil3,4,5. Traditional control measures, such as chemical fungicides and crop rotation, have limited effectiveness and pose environmental concerns6,7,8,9. Therefore, there is a growing need to explore sustainable, non-toxic alternatives for managing this phytopathogen10,11,12,13,14. In this context, the use of natural bioactive compounds derived from microorganisms has gained considerable attention15,16,17,18,19.

Cyanobacteria, often referred to as blue-green algae, are photosynthetic prokaryotes known for their remarkable adaptability to diverse and extreme environments. These microorganisms produce a wide range of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, and other bioactive compounds, which have been demonstrated to possess antimicrobial, antifungal, and antiviral properties20,21. Several studies have demonstrated the antifungal potential of cyanobacterial extracts against phytopathogenic fungi. For instance, extracts from species such as Nostoc sp., Oscillatoria sp., and Anabaena sp. have shown significant antifungal activity against pathogens like Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus flavus, and Rhizoctonia solani3,4,17,22,23,24. These findings highlight the potential of cyanobacteria as natural biocontrol agents for managing plant diseases, thereby reducing reliance on chemical pesticides and promoting sustainable agriculture25. Sub-aerial cyanobacteria, in particular, thrive in extreme habitats such as building facades and rocky surfaces, where they form microbial biofilms. These extremophiles have recently been identified as a potential source of bioactive compounds with various applications, including plant disease management26,27.

The current study focuses on a cyanobacterium, Desertifilum dzianense, isolated from the stone walls of monuments in the Bolangir district of Odisha, India. This species was selected for its potential to produce secondary metabolites with antifungal properties. The research aimed to evaluate the phytochemical composition and antifungal efficacy of the cyanobacterial extracts against Agroathelia rolfsii, the causal agent of collar rot in chickpea. The study involved phytochemical screening, characterization of bioactive compounds, and assessment of their antifungal activity through in vitro experiments.

Materials and methods

Microbial cultures

The sample, a cyanobacterium, D. dzianense (Gene bank accession number ON358232.1) isolated from the stone wall of monuments from Bolangir district of western region, Odisha available as specimen at Botany Laboratory (Voucher No. BOT/UAT-046) was taken as an experimental organism.

Sub-culturing and mass production of the sample

A small amount of homogenized sample was transferred into clean sterile conical flasks containing BG-11 (N+) media. The inoculated conical flasks were kept in culture rack under the white fluorescent light maintaining a condition of 3000 lx and 28 ± 1 °C for 15 days. A state of 16 h light and 8 h dark was maintained during the incubation period28.

Harvesting of biomass

After 15 days of incubation, the biomass was harvested and centrifuged at 8500 rpm for 20 min. The pellet was collected, dried in the shade and ground to a fine powder using mortar and pestle. The powder was stored in glass bottle under cold conditions.

Preparation of crude extract

A 2 g of the powdered sample was wrapped in a filter paper and tied using a long thread making packets. The prepared packets were dipped in 50 ml of the desired solvent in air tight containers. The solvents used in the experiment were Acetone, Methanol, Benzene, Hexane and an aqueous solution. These were exposed to freezing and thawing cycles. The air tight containers were exposed to repeated cycles of freezing at -20 °C and thawing at 25 °C conditions till the colour change of the powdered sample occurs29.

Phytochemical screening of crude extract

Phytochemical screening of the crude extracts for the detection of secondary metabolites like alkaloids, phenols and flavonoids were carried out by following the standard protocols30,31.

Test for alkaloids

Three ml of the crude extract was dissolved in 3 ml of dilute Hydrochloric acid and filtered using filter paper. The filtrate was tested for presence of alkaloids by Dragendorff’s test, Mayer’s test, and Wagner’s test.

Test for phenolic compound

The presence of phenolic compound has been tested by Ferric Chloride test. Few drops of neutral 5% ferric chloride solution were added to 1 ml of crude extract dissolved in 5 ml of distilled water. Observation of dark green colour indicated the presence of phenolic compounds.

Test for flavonoids

The presence of flavonoid has been tested by Alkaline Reagent Test. 1 ml of crude extract was added to 10% Ammonium hydroxide (alkaline reagent) solution. Occurrence of yellow fluorescence indicated the presence of flavonoids.

Purification of bioactive compound from crude extract of sub-aerial cyanobacteria through thin layer chromatography (TLC)

The crude extracts were purified using Thin Layer Chromatography for obtaining bands and each band was tested for antimicrobial property. The purification was carried out using a preparatory TLC plate with silica gel as stationary phase (H-60 Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and a mixture of acetone and hexane in the ratio 1:1 as mobile phase. 100 µl of each rich fraction of potential crude extracts of potential was loaded on the TLC plates and allowed to run over the stationary phase. The bands were visualized under visible light to obtain the clear bands followed by calculation of the Retention Factor (Rf) of each band. All the bands were scraped out separately using sharp blade and dissolved in 3 ml of respective solvents separately. Their bioactivities were tested against the test pathogen using Agar Well Diffusion methods to select the potent extract showing best results32. The crude extracts showing the highest antimicrobial properties against plant fungal pathogen during screening were further purified to obtain the single band.

Selection of the potent organic solvent

All the bands obtained from the crude solvents showing strong positive tests for presence of secondary metabolites were screened separately using Agar Well Diffusion technique32,33. The band of the potential solvent showing clear inhibition zone was purified further using TLC and the scrapped purified band dissolved in that particular solvent was further used for the antimicrobial susceptibility test. The Antimicrobial activity Indexes (AI) of the respective compounds were calculated using the following formula:

Fungal strain collection

The fungal strain was collected from the farm land of Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology, Bhubaneswar for the experimental purpose. The diseased stem of chickpea plant was collected and surface sterilized by 70% ethanol and kept in 3% sodium hypochlorite for 1 min for commercial bleaching34. The fungus affected part was inoculated in the Potato Dextrose Agar plates and incubated at 22 °C in dark. The pure strain was maintained in slants on Potato Dextrose Agar medium (Food and Drug Administration, USA) in the Department of Botany, College of Basic Science & Humanities, OUAT. The fungal pathogenic strain collected from the Chickpea plant was identified as Agroathelia rolfsii through 18 S rRNA molecular sequencing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

Agar Well Diffusion technique was used to test antifungal activity of the crude extracts against the test fungal pathogen32. The potential antifungal activities of sub-aerial cyanobacteria strain were assessed using the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines (NCCLS) for Agar Well Diffusion assay according to Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines. The fungal sample was spread uniformly over the PDA plates using a clean sterile swab. Wells of size 8 mm diameter were created at the centre of the pathogen- inoculated agar plates. The bottoms of the wells were sealed with 1% soft agar and loaded with a total of 10 µl (MIC concentration) of the potential extract solution. As the positive control, antifungal (Thiram-10 mg/ml) agent was used and for the negative control, wells without extract and containing only the potential organic solvent were included in the assays. The purified bands were dissolved in the appropriate solvent for the experiments and all experiments were carried out in triplicate. The fungal plates were incubated at 22 °C and the inhibition zone was observed after 48–72 h.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The lowest concentration of the antimicrobials at which the zone of inhibition appears inhibiting the growth of the microorganism is called as the Minimum Inhibition Concentration (MIC). The values were determined using the micro dilution method described in the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines32. Purified compounds were serially diluted with respective solvents to obtain extract concentrations ranging from 0.312 mg/ml to 10 mg/ml. These extracts were then poured into the wells of PDA fungal plates. The highest dilution at which no pathogen growth was observed was considered the extract’s Minimum Inhibitory Concentration. Each extract was treated in the same way.

Identification of bioactive compound

Partial characterization of the active compound of potent isolates through UV- visible and FTIR spectroscopy analysis.

The extract having highest active component and showing best antifungal action against plant fungal pathogen was selected and examined using UV/Vis and FTIR spectroscopy35,36. The active component received from the extract of the powerful isolate was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min and filtered using Whatman No.1 filter paper under a high-pressure vacuum pump for UV-Vis and FTIR spectrophotometer measurement. The sample was diluted to a ratio of 1:10 in the same solvent. The active compound extracted from each solvent extract was scanned in the wavelength range of 200 800 nm using a Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer, and the distinctive peaks were identified. To identify their functional groups, an FTIR analysis was done using a Nicolet 6700 spectrophotometer from the United States.

Identification of chemical nature of active spot/band by Bio-autography

After obtaining the single purified band/spot of the potent solvent showing antimicrobial property, the plates were bio-autographed for identification of the chemical nature of the obtained band37. The TLC plate was visualized under the visible light to obtain the colour spot and the Rf value was calculated. Direct bioautography on TLC plate was used to determine the chemical nature of the band obtained from the selected potent solvent by spraying with Dragendorff’s reagent for alkaloid38.

Statistical analysis

All the data obtained from the experiments were expressed as mean ± SD of three replicates.

Results

During the study, a cyanobacterium identified as D. dzianense (ON358232.1), isolated from the stone sculpture, Surda Shiv temple from Bolangir district of western region, Odisha available as specimen at Botany Laboratory, College of Basic Science and Humanities, OUAT were taken as an experimental organism (Fig. 1a-d) for specific phytochemical screening and evaluation of anti-fungal potential against soil borne fungal pathogen of collar rot of Chick pea.

Habitat and light microscopy images of D. dzianense (a) Stone sculpture in Surda Shiv Temple in Bolangir district of Western Odisha showing the sampling point (pointed with red arrow). (b) Filaments of D. dzianense. (c) Filament showing elongated apical cell. (d) Matured filament showing formation of hormogonia. (Scale bar: b-d = 10 μm), (e) & (f) Showing the photographs of mass production through sub culture of cyanobacterium under laboratory condition.

Sub-culturing and mass production of the sample

The provided sample D. dzianense was incubated in the culture rack under the white fluorescent light maintaining a condition of 3000 lx and 28 ± 1 °C for 15 days where 16:8 h light and dark was maintained28. After the incubation, green mass growth of the cyanobacteria was observed in the conical flasks (Fig. 1e, f).

Preparation of crude extract of experimental organism using Polar and non- Polar solvents

To prepare the crude extract of a cyanobacterium taken as experimental organism, selected polar and non-polar solvents such as an aqueous solution (as control), acetone, methanol, benzene and hexane, were used and exposed to freeze-thaw cycles. Two grams of powdered form cyanobacteria was used for 50 ml of solvent. Repeated cycles of freezing (-20 °C) and thawing (25 °C) led to the colour change of the powdered form of the sample indicating the completion of extraction39,40,41. The results are depicted in Fig. 2.

Screening of phytochemicals of the Cyanobacterium crude extract

The preliminary screening of phytochemicals of the cyanobacterium, D. dzianense was performed through various qualitative tests. Selected polar and non-polar solvents such as aqueous solution as control, methanol, ethanol, benzene and hexane were used for this purpose. Among these solvents used, methanol as polar solvent was considered best for extracting bioactive compounds or secondary metabolites from the studied cyanobacterium. However, the phytochemical screening indicated the presence of bioactive compounds in acetone and benzene solvents in higher degree than hexane. The presence of alkaloids and phenolic compounds was found in acetone and methanol while it was absent in hexane and benzene. The test for flavonoids was negative for all the taken solvents. The phytochemical components from selected solvents of the cyanobacterium crude extract are depicted in Table-1 and shown in Fig. S1 (a-e).

Fungal strain collection, isolation and culturing

The disease infected stem of Chickpea plant was collected during the month of April-May month, 2024 from the farmland of Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology, Bhubaneswar and were surface sterilized by 70% ethanol and kept in 3% sodium hypochlorite for 1 min34. Later, the fungus affected part was inoculated in the PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar) media plates and were incubated at 22 °C in dark. On the third day of incubation, there was initiation of white mycelia growth and by the fifth day the plate was fully covered with the white mycelia. The round brown-coloured structures called sclerotia were observed between seventh to tenth days of incubation (Fig. 3a-d).

Identification of fungal strain

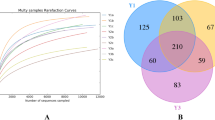

Molecular sequencing and phylogenetical analysis

The DNA isolated from the fungal culture was amplified with 18s rRNA specific Primer where a single discrete PCR amplicon band of ~ 600 bp was observed. Further application of Sanger Sequencing resulted in the identification of the fungal strain to be Agroathelia rolfsii (Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc.) as it showed high similarity with top based on nucleoside homology and phylogenetical analysis (Figs. 4 and 5). The organism was submitted to the NCBI Gene Bank to get Accession number of PQ496901.

DNA was isolated from the culture. Quality was evaluated on 1.8% Agarose Gel; a single band of high-molecular weight DNA has been observed. Isolated DNA was amplified with 18s rRNA Specific Primer (ITS1 and ITS4) using Veriti® 96 well Thermal Cycler. A single discrete PCR amplicon band of ~ 600 bp was observed.

Purification of crude extract of a Cyanobacterium through thin layer chromatography

The solvent crude extracts of a cyanobacterium, D. dzianense showing positive results in high degree were purified using Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) to obtain bands. For the purification process, silica gel was taken as stationary phase (H-60 Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and a mixture of acetone and hexane in the ratio 1:1 as mobile phase. The initial phytochemical screening showed positive results for alkaloids in acetone, methanol and benzene in higher degree, whereas, for phenolic compounds accept acetone and methanol showed response to it. Based on the results, three different crude extracts of acetone, methanol and benzene were selected respectively. Acetone solvent showed three bands, methanol showed four bands and benzene was seen with a single band (Fig S 2 a-c).

Screening of potential band and solvent for antifungal activity against Agroathelia rolfsii (PQ496901) using agar well diffusion method

All the bands obtained from the three crude solvents of acetone, methanol and benzene that showed strong positive tests for presence of alkaloids and phenols were screened separately using agar well diffusion technique for observation of clear Inhibition zone32. Each band was separately scrapped and mixed with the respective solvents in the Eppendorf tube and centrifugation was performed. 100 µl of centrifuged supernatant were tested in separate wells in the respective fungal agar plates. The three bands (1, 2 and 3) of acetone extract did not show any zone of inhibition (Fig. 6a). Same negative result was shown by the single band of benzene extract with no zone of inhibition (Fig. 6b). Out of the four bands, one band (M2) of methanol extract showed a clear zone of inhibition (Fig. 6c). Hence, from the above observation, methanol solvent was selected for the antimicrobial susceptibility test.

Anti-fungal activity test

Initial screening of crude extract for antimicrobial efficacy

For primary screening of different selected solvent extracts of the cyanobacterium strain, D. dzianense, agar well diffusion method was performed. Among all the solvents used, only methanol extract revealed anti-fungal activities in terms of zone of inhibitions against the targeted soil borne fungal pathogen. Generally, the degree of anti-fungal activity of different extracts varies in terms of zones of inhibition. More than or equal to 10 mm zone of inhibition was considered as a standard for the potency of crude extract against Agroathelia rolfsii (PQ496901)42.

Fractionation of Cyanobacterium crude extracts through thin layer chromatography (TLC) and their antimicrobial activities against Agroathelia rolfsii (PQ496901)

The methanol extract of the cyanobacterium strain was purified through TLC for their further anti-fungal analysis. Results estimated through TLC analysis from purified compound, was examined for its anti-fungal activities (zone of inhibition and anti-fungal activity index respectively) of the solvent extracts against soil borne fungal pathogen is summarized in Table-2 and 3.

The compound, M-2 of methanol extract of D. dzianense showed anti-fungal activity against Agroathelia rolfsii (PQ496901) with high inhibition of 12 ±1.0 mm. The commercial antifungal, Thiram taken as positive control was found with an inhibition zone of 10.6 ± 0.5 mm indicating that the methanolic extract (M-2 band) showed slightly better anti-fungal activities in comparison to the positive control (Thiram) examined (Fig. 7a-c). Phytochemical constituents of compounds obtained from methanol fractions of D. dzianense, henceforth, were subjected to UV-Vis, FTIR analysis and bioautography. The MIC value of active fractions was determined by using the tube dilution technique.

Isolated TLC bands of cyanobacterial extract and its bioautography

Chemical nature of purified bands obtained through TLC were determined by spraying with Dragendorff’s reagent for alkaloids and 10% FeC13 for phenolic compounds38. By bioautography, presence of alkaloids was observed in the bioactive compounds of methanol extract (M-2, Rf value = 0.90) of D. dzianense which showed brownish yellow colour change (Fig S 3).

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of TLC purified active compounds of cyanobacterial strain

Tube dilution technique was adopted for the calculations of MIC value of active fractions. The MIC value of methanol extract of purified compounds M-2 with Rf value − 0.90 obtained from methanol extract of the sub-aerial cyanobacterium D. dzianense exhibit significant antifungal activity with least MIC value of 10 mg/ml. However, Thiram (positive control) also exhibited least MIC value (10 mg/ml) with highest degree of antifungal activity (Fig. 8and Fig. 9). The antimicrobial index of compound M-2 of methanol extract was calculated in Table 3.

Characterization of purified active compounds using UV-Vis and FT-IR analysis

UV-Vis and FTIR were used to characterize the antifungal active compounds in methanol extract of the cyanobacterial isolates. UV-vis analysis of compound-M2 (methanol extract) obtained with Rf value 0.90 exhibited the peak at 661 nm (Fig S 4). Functional groups of the potent purified compounds produced by Cyanobacteria species were characterized by FTIR analysis (Fig S 5). The band that occurred at 3307.46 cm− 1 confirmed the presence of O-H monomeric carboxylic hydrogen bonded alcohols, phenols and the band that occurred at 2948.09 cm− 1 and 2835.59 cm− 1 represented the CH and CH2 stretching aliphatic groups. Band at 2206.18 cm− 1 represented C = C conjugated and carbon-carbon triple bonds. Similarly, bands at 1655.8 cm− 1 confirmed the presence of C = O, C = C, C = N aromatic rings and band at 1449.33 cm− 1 confirmed the presence of CH aliphatic bending groups. Band 1411.56 cm− 1 represented the stretching –C = O inorganic carbonates whereas the band at 1112.16 cm− 1 represented the C-O-C polysaccharides. The band at 1016.45 cm− 1 showed C-C, C-O, C-O-C and C-O-P of saccharides and the band at 576.24 cm− 1 confirmed stretching C-Br groups.

Discussion

The overreliance on synthetic fungicides in modern agriculture has raised significant environmental and health concerns, including the emergence of resistant fungal strains, contamination of soil and water resources, and harmful impacts on non-target organisms. In light of these issues, biocontrol strategies that harness the natural antagonistic potential of microorganisms offer a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative for managing plant diseases3,4,5,6,7. Cyanobacteria, in particular, have garnered attention for their capacity to produce a wide array of bioactive secondary metabolites with antimicrobial properties, making them promising candidates in the search for novel biopesticides10,17,19.

In the present study, D. dzianense, a sub-aerial cyanobacterial strain isolated from monument stone crusts in Odisha, was evaluated for its antifungal activity against Agroathelia rolfsii, the causal agent of collar rot in chickpea. Among various solvent extracts tested, the methanolic extract exhibited the most pronounced antifungal activity, highlighting methanol as the most effective solvent for extracting active compounds from this cyanobacterial strain.

Phytochemical screening revealed the presence of key secondary metabolites, particularly alkaloids and phenolic compounds, in the methanol, acetone, and benzene extracts, while the hexane extract lacked these constituents. The absence of antimicrobial activity in the hexane extract corroborated the phytochemical results. Previous research has established that naturally derived alkaloids and phenolics possess broad-spectrum antifungal properties, supporting their potential application as effective biocontrol agents in agriculture.

In antimicrobial assays, the methanolic fraction labeled M-2 showed a clear zone of inhibition measuring 12.0 ± 1 mm against A. rolfsii, exceeding the 10.6 ± 0.5 mm inhibition zone produced by the commercial fungicide Thiram. This result suggests that the bioactive compounds in the methanol extract possess significant antifungal efficacy, potentially exceeding that of conventional chemical treatments. Both M-2 and Thiram shared a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value of 10 mg/ml, further supporting the potency of the cyanobacterial extract.

To elucidate the nature of the active compounds, UV-Vis and FTIR spectroscopy were employed. The analyses revealed the presence of multiple functional groups—including CH and CH₂ aliphatic stretches, aromatic C = C and C = N rings, O-H bonded alcohols, carbonyl (C = O), and carboxylic functionalities—indicating a chemically diverse profile of secondary metabolites. The dominance of alcohol and alkaloid-related functional groups in the FTIR spectrum points toward the alkaloidal nature of the antifungal constituents.25,42,43,44,45.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that D. dzianense is a promising natural source of antifungal compounds, with methanol proving to be the most suitable solvent for extracting these bioactive agents. The observed antifungal activity against A. rolfsii underscores the potential of this cyanobacterium as a biocontrol agent in chickpea cultivation. Future research, including field trials and toxicity assessments, is essential to confirm its practical applicability and safety for large-scale agricultural use.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Bank with the primary accession code PQ496901.

References

Arriagada, O. et al. A comprehensive review on Chickpea (Cicerarietinum L.) breeding for abiotic stress tolerance and climate change resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6794–6818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23126794 (2022).

Maleki, H. H. et al. Exploring resistant sources of Chickpea against fusariumoxysporum f. Sp. ciceris in dryland areas. Agri 14, 824–832. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060824 (2024).

Sharma, S. et al. The combination of α-Fe2O3NP and Trichoderma sp. improves antifungal activity against Fusarium wilt. J. Basic. Microbiol. e2400613. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.202400613 (2025).

Anbalagan, S. A. et al. Deciphering the biocontrol potential of Trichoderma asperellum (Tv1) against Fusarium-nematode wilt complex in tomato. J. Basic. Microbiol. e2400595, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.202400595 (2024).

Praveen, V. et al. Harnessing Trichoderma asperellum: Tri-Trophic interactions for enhanced black gram growth and root rot resilience. J. Basic. Microbiol. e2400569. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.202400569 (2024).

Dave, A. et al. Harnessing plant growth-promoting and wilt-controlling biopotential of a consortium of actinomycetes and mycorrhizae in pigeon pea. J. Phytopathol. 172, e13399. https://doi.org/10.1111/jph.13399 (2024).

Vinothini, K. et al. Rhizosphere engineering of biocontrol agents enriches soil microbial diversity and effectively controls Root-Knot nematode. Microb. Ecol. 87, 120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-024-02435-7 (2024).

Najla, A. A. et al. In Silico analysis of LPMO Inhibition by ethylene precursor ACCA to combat potato late blight. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 36, 103436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103436 (2024).

Showkat, M. et al. Optimization of fermentation conditions of Cordyceps militaris and in-silico analysis of antifungal property of cordycepin against plant pathogens. J. Basic. Microbiol. e2400409, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.202400409 (2024).

Aktar, S. N. et al. Beneficial microbes in plant health, immunity and resistance. In: (eds Mathur, P. & Roy, S.) Plant Microbiome and Biological Control. Sustainability in Plant and Crop Protection, vol 20. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-75845-4_1 (2025).

Chaithra, M. et al. Fungal Bio-stimulants: Cutting-Edge bioinoculants for sustainable agriculture. In: (eds Mathur, P. & Roy, S.) Plant Microbiome and Biological Control. Sustainability in Plant and Crop Protection, vol 20. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-75845-4_13 (2025).

Yatoo, A. M. et al. Effect of macrophyte biomass-based vermicompost and vermicompost tea on plant growth, productivity, and biocontrol of Fusarium wilt disease in tomato. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 60, 103320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103320 (2024).

Krishna, N. R. U. et al. Triamcinolone acetonide produced by Bacillus velezensis YEBBR6 exerts antagonistic activity against Fusarium oxysporum f. Sp. Cubense: A computational analysis. Mol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-023-00797-w (2023).

Sudha, A. et al. Unraveling the tripartite interaction of volatile compounds of Streptomyces rochei with grain mold pathogens infecting sorghum. Front. Microbiol. 13, 923360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.923360 (2022).

GhadirnezhadShiade, S. R. et al. Nitrogen contribution in plants: recent agronomic approaches to improve nitrogen use efficiency. J. Plant. Nutr. 47 (2), 314–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2023.2278656 (2024).

Marteau-Bazouni, M. et al. Grain legume response to future climate and adaptation strategies in europe: A review of simulation studies. Eur. J. Agron. 153 (2), 127056–127065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2023.127056 (2024).

Paliwal, K. et al. Enhancing biotic stress tolerance in soybean affected by Rhizoctonia Solani root rot through an integrated approach of biocontrol agent and fungicide. Curr. Microbiol. 80, 304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-023-03404-y (2023).

Kadiri, M. et al. Pan-genome analysis and molecular Docking unveil the biocontrol potential of Bacillus velezensis VB7 against. Phytophthora infestans Microbiol. Res. 268, 127277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2022.127277 (2023).

Ruparelia, J. et al. Bacterial secondary metabolites (B-SMs): empowering agriculture against fungal disease challenges. In: (eds Mathur, P. & Roy, S.) Plant Microbiome and Biological Control. Sustainability in Plant and Crop Protection, vol 20. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-75845-4_12 (2025).

Mehdizadeh Allaf, M. & Peerhossaini, H. Cyanobacteria: model microorganisms and beyond. Microorganisms 10 (4), 696. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10040696 (2022).

Kumla, D. et al. Specialized metabolites from cyanobacteria and their biological activities. In: (eds Lopes, G., Silva, M., & Vasconcelos, V.) The Pharmacological Potential of Cyanobacteria in Academic Press, 21-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821491-6.00002-8 (2022).

Panigrahi, S. et al. Antibacterial activities of Scytonema Hofman extracts against human pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 7 (5), 123–126 (2015).

Sahu, E. et al. Phytochemical screening of a corticolous Cyanobacterium Hassalia Byssoidea hass. Ex born. Et flah. For antibacterial and antioxidant activity. WJPPS 6 (3), 1161–1172 (2017).

Bhakat, S. et al. Antibacterial activity of desiccated CyanobacteriumAnabaena sp. isolated from terracotta monuments of bishnupur, West Bengal. IJPSDR 12 (2), 1333–1340 (2020).

Khan, P. A. et al. Valorization of Coconut Shell and Blue Berries Seed Waste into Enhance Bacterial Enzyme Production: Co-fermentation and Co-cultivation Strategies. Indian J Microbiol., 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12088-025-01446-3 (2025).

Kumar, J. et al. Cyanobacteria: applications in biotechnology. Cyanobacteria 327, 346 (2019).

Safari, M. et al. Biological activity of methanol extract from Nostoc sp. N42 and Fischerella sp. S29 isolated from aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. InterJAlgae 21 (4), 373–391 (2019).

Rippka, R. et al. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure culture of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111 (2), 1–61. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-111-1-1 (1979).

Kumar, V. & Malik, D. P. Trends and economic analysis of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) cultivation in India with special reference to Haryana. Legume Research-An Int. J. 45 (2), 189–195 (2022).

Raaman, N. Phytochemical Techniques. New India Publishing Agency, New Delhi, India, 287. (2006).

Roy, P. et al. Applications of algal based therapeutics in human health. Bombay Technologist. 10 (2), 01–08 (2022).

Wayne, P. A. Evaluation of detection capability for clinical laboratory measurement procedures; approved guideline. Clin. Lab. Stand. Inst. (2012).

WellingPG Oral controlled drug administration. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 9 (7), 1185–1225. https://doi.org/10.3109/03639048309046316 (1983).

Njambere, E. N. et al. Stem and crown rot of Chickpea in California caused by Sclerotinia trifoliorum. Plant. Dis. 92 (6), 917–922. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-92-6-0917 (2008).

Rastogi, R. P. & Incharoensakdi, A. UV radiation-induced accumulation of photoprotective compounds in the green Alga Tetraspora sp. CU2551. PPB 70 (4), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.04.021 (2013).

Bakir, E. M. et al. Cyanobacteria as Nanogold factories: chemical and antimyocardial infarction properties of gold nanoparticles synthesized by Lyngbya majuscule. Mar. Drugs. 16 (6), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/md16060217 (2018).

Dewanjee, S. et al. Bioautography and its scope in the field of natural product chemistry. J. Pharm. Anal. 5 (2), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2014.06.002 (2015).

Waldi, D. Spray Reagents for Thin-layer Chromatography. Thin-Layer Chromatography: A Laboratory Handbook, 483–502. (1965).

Bennett, A. & Bogorad, L. Complementary chromatic adaptation in a filamentous blue-green Alga. JCB 58 (2), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.58.2.419 (1973).

Kumar, D. et al. Extraction and purification of C-phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis (CCC540). Indian J. Plant. Physiol. 19, 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40502-014-0094-7 (2014).

De Los Ríos, A. et al. Ultrastructural and genetic characteristics of endolithic cyanobacterial biofilms colonizing Antarctic granite rocks. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 59 (2), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00256.x (2007).

Saranraj, P. et al. Plant Growth-Promoting and Biocontrol Metabolites produced by Pseudomonas fluorescence. In: Secondary Metabolites and Volatiles of PGPR in Plant-growth Promotion. R. Z. Sayyed and Virgilio Gavicho Uarrota (eds), Springer, Cham, pp 349 – 81. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07559-9_18

Sagar, A. et al. in Bacillus Subtilis: A Multifarious Plant Growth Promoter, Biocontrol Agent, and Bioalleviator of Abiotic Stress. Bacilli in Agrobiotechnology. 561–580 (eds Islam, M. T., Rahman, M. & Pandey, P.) (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85465-2_24

Swain, S. S. et al. Antibacterial activity, computational analysis and host toxicity study of thymol-sulfonamide conjugates. Biomed. Pharmacother. 88, 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.036 (2017).

Chittora, D. et al. Cyanobacteria as a source of biofertilizers for sustainable agriculture. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 22 (2), 100737–100742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2020.100737 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. Conceptualization, writing–original draft, A.N. Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing–original draft, M.B. conceptualization, formal analysis, validation, supervision, writing-review, editing. G.S. data curation, software, visualization. S.S.A., J.B. and R.S. Writing-Review and editing, formal analysis, validation and funding acquisition, D.K.B. data curation, software. V.A. data curation, software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, L., Nayak, A., Behera, M. et al. Antifungal potential of Cyanobacterium Desertifilum dzianense against collar rot pathogen in Chickpea. Sci Rep 15, 23740 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08395-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08395-3