Abstract

To address critical thermal management challenges in low-temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFC), this investigation establishes a three-dimensional steady-state numerical model of a single-channel PEMFC system. The developed model systematically examines liquid cooling system characteristics through parametric analysis of four key operational factors: (1) coolant inlet temperature (2) counter-flow configuration (3) coolant velocity (0.05–7 m/s range) (4) cooling channel cross-sectional geometry. Numerical results reveal three fundamental findings: 1.Cell voltage reduction induces intensified heat generation, causing the proton exchange membrane (PEM) to maintain the highest temperature among cell components (ΔT = 8.3 °C maximum observed). 2.Optimized counter-flow arrangements enhance thermal uniformity, achieving 23.6% reduction in PEM temperature gradient compared to co-flow configurations. 3.While increasing coolant velocity from 0.05 to 2 m/s decreases average PEM temperature by 5.2 °C (Q = 18.6 W/cm2), further velocity escalation to 7 m/s yields diminishing returns (< 0.5 °C improvement) with concomitant 68.4% pressure drop increase. Notably, triangular cooling channels demonstrated superior thermal performance with 75.77 °C average PEM temperature, albeit requiring 42% higher pumping power compared to conventional rectangular designs. These findings provide critical insights for thermal management system optimization in next-generation PEMFC applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

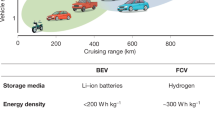

The active development of clean energy and the promotion of a transition towards a green and low-carbon economy and society are essential pathways for China to achieve peak carbon emissions and carbon neutrality. Hydrogen energy holds a strategically significant position in the steady implementation of the "dual-carbon" strategy due to its abundant availability, environmentally friendly characteristics, and diverse applications. The Low-Temperature Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) is an electrochemical power generation device that utilizes hydrogen and oxygen as reactants. This cell offers several advantages, including zero emissions, rapid start-up, low operating temperatures, sustainability, and a broad range of applications. It serves as a prominent symbol of hydrogen energy utilization and constitutes a critical component of the energy strategies employed by various countries1,2,3,4,5.

The theoretical conversion efficiency of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFC) is regarded as high; however, in practice, it typically ranges from 40 to 60%. The remaining energy is dissipated as waste heat, which must be expelled from the cell6,7. The voltage and current produced by a single proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) are relatively low. Consequently, to generate sufficient power for electrical equipment, it is necessary to connect hundreds of thousands of cells in series to form a power stack. The operational temperature requirement for this power stack ranges from 60 °C to 80 °C. If the waste heat generated during operation is not effectively dissipated, it can adversely affect the performance of the stack and potentially lead to damage. Therefore, efficient heat dissipation is critical for the large-scale application of PEMFC technology.

Current cooling methods for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) stacks include air cooling, liquid cooling, and phase-change cooling. Among these, liquid cooling technology is predominantly utilized in the thermal management of fuel cells due to its superior heat dissipation, precise temperature control, enhanced design flexibility, and broad applicability. The coolant flow channel is typically integrated into the bipolar plate, making its design a critical factor influencing the internal temperature distribution of the cell as well as its overall performance. Consequently, numerous researchers have proposed and evaluated various flow field designs8,9. Peng et al.10 Baek et al.11 contributed significantly to this area of study by investigating the direct current field, wave flow field, and grid flow field through numerical simulations. They analyzed the average temperature of the stack, temperature uniformity, and maximum temperature difference to evaluate the impact of the flow field on thermal management. Their results indicated that while the grid flow field can significantly enhance oxygen supply and facilitate the removal of liquid water, it is associated with the poorest temperature uniformity and the largest temperature difference within the cell. These factors hinder the effective design of thermal management systems for the stack. The authors numerically simulated fluid flow and heat transfer in a large cooling plate, omitting the electrochemical mass transfer processes of the cell. They evaluated six different coolant flow configurations based on maximum temperature, temperature uniformity, and pressure drop characteristics. The results indicated that the flow field design significantly influences temperature distribution, with the multi-channel serpentine design exhibiting the best temperature uniformity. Furthermore, the serpentine design featuring five parallel flow channels was identified as the optimal configuration.

This study established a fuel cell model featuring coolant channels designed for countercurrent flow of hydrogen and air. The investigation focused on the effects of coolant velocity, inlet temperature, coolant flow direction, and the number of cooling channels on the cell’s output. The findings indicate that the cooling inlet temperature directly influences the operating temperature of the stack. Furthermore, liquid water formation near the cathode outlet can be mitigated when the liquid and air flows are aligned. Although reducing the number of cooling channels while increasing the coolant flow rate slightly enhances temperature uniformity across the stack, it also leads to increased parasitic power losses. Therefore, it is inadvisable to pursue a uniform temperature distribution in the stack indiscriminately.

et al.12. The optimal inlet temperature for the coolant was identified as 343.15 K. Additionally, the surface Nusselt number of the wavy flow field exceeds that of the direct current (DC) field under equivalent operating conditions.

Ben et al.13 developed an electrochemical heat and mass transfer model for fuel cells with wavy coolant flow paths, concluding that optimal cell performance occurs when the coolant flow direction aligns with that of the oxygen. This finding contrasts with the conclusions drawn by Liu.

Song et al.14 designed four novel types of cooling plate flow fields, demonstrating that local serpentine channel designs can enhance coolant fluidity, prevent local reflux, promote a more uniform temperature distribution, and mitigate localized overheating of the cell. Other researchers have proposed various methods to improve thermal management, including the incorporation of metal foam into flow field designs, the integration of heat pipes, the embedding of separate channels within the cell, and modifications to the cathode flow field. While these methods have proven effective, their universal application remains limited due to technological constraints15,16,17,18,19.

Sajad Rezazadeh et al.20established a three-dimensional single-phase model of proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), incorporating gas distribution channels and membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs). Utilizing finite volume computational fluid dynamics (CFD) techniques, they conducted numerical investigations on direct current single-pass fuel cells and compared the performance of serpentine channels with conventional straight channels. The study demonstrated that channel geometry significantly influences fuel cell performance, with variations in channel design affecting species distribution, mass transfer efficiency, and current density, thereby impacting overall system performance.

Wei-wei Yuan et al.21 analyzed the temperature characteristics of air-cooled PEMFCs and achieved temperature distribution control by optimizing operating temperature and minimizing temperature gradients. They developed a three-dimensional numerical model to predict temperature distribution along the cooling channel direction under different air velocities, constructed a multi-node control-oriented model, and designed a cooling air flow direction adjustment strategy based on finite state machine control and a proportional-integral (PI) control strategy for air flow velocity. Experimental validation on a 1.2 kW PEMFC system confirmed that this temperature control approach enhances fuel cell performance while maintaining temperature gradients within 0.5 °C.

Nima Ahmadi et al.22 developed a comprehensive three-dimensional single-phase CFD model of PEMFCs, including gas distribution channels and MEAs, and solved conservation equations governing flow channels, gas diffusion electrodes, catalytic layers, and membrane regions using finite volume methods. Their analysis revealed that a reduced anode transfer coefficient leads to decreased oxygen and water mass fractions, as well as diminished current density, with numerical results validated against existing experimental data.

The design of the cooling channel is crucial for the cooling of PEMFC. In this paper, a single-channel physical model of liquid-cooled PEMFC is established based on CFD software, and a correct mathematical model is used to simulate the internal reaction and heat production in the working engineering of PEMFC. We studied the effects of coolant inlet temperature, different flow directions, coolant flow rate, and changes in cooling channel cross section on the temperature field of the cell, especially the membrane temperature, to provide a theoretical basis for the development of high-performance PEMFC.

Numerical simulation

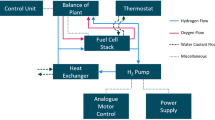

Numerical simulation is used to analyse the liquid-cooled PEMFC. This section describes the mathematical model, physical model, mesh model, and boundary conditions used in the simulation.

Assumptions of reasonableness of numerical calculations

The real internal reaction of the cell contains several dimensions such as electrochemistry, phase transition, heat transfer, etc., and the following necessary and reasonable assumptions are made in order to facilitate the numerical simulation.

-

The cell is operated under steady operation state conditions.

-

The flow of the coolant is ideal, laminar and incompressible.

-

The reactants are pure hydrogen and air, which are considered ideal gases with a laminar and compressible flow.

-

The gas diffusion layer and the catalytic layer are porous media and their physical parameters are considered isotropic.

-

Resistance due to contact between cell parts is not taken into account in the calculations.

-

The effect on the cell reaction due to gravity is not taken into account.

-

Neither air nor hydrogen will cross the proton exchange membrane.

-

The water produced by the reaction is liquid water and the change in cell temperature due to the phase change of water is not considered.

Mathematical model

Equation of conservation of mass:

According to the law of conservation of mass, the continuity equation (mass conservation equation) of PEMFC is :

In the formula: \(\varepsilon\) is the porosity of the porous medium; \(\rho\) is the density of the gas mixture; \(Sm\) is the mass source term.

Momentum conservation equation:

The momentum equation of PEMFC is expressed as:

In the formula: \(\mu\) is hydrodynamic viscosity; \(Su\) Is the momentum source term。

In the gas channel, the momentum equation can be transformed into the Navier–Stokes equation. In the gas diffusion layer, assuming that the porous medium is homogeneous and the fluid flow state is laminar, ignoring the internal loss term in the momentum source term, the momentum equation is simplified to Darcy’s law:

In the formula: \(K\) It is the penetration rate of the porous medium in the gas diffusion layer.

Energy conservation equation:

Since the heat dissipation caused by the viscosity of the fluid is not considered inside the fuel cell, the energy conservation equation of the steady-state PEMFC is:

In the formula: \(c_{p}\) is the specific heat capacity of the gas mixture at constant pressure. \(k\) Is the thermal conductivity of the gas mixture; \(S_{T}\) is the heat source term, It mainly includes the heat generated by electrochemical reaction, overpotential, impedance and water phase transition process.

Component conservation equation:

The internal chemical reactions of fuel cells mainly involve the components of reactants such as hydrogen, oxygen, and product water, so the conservation equation of PEMFC components is:

In the formula: \(c_{i}\) is Concentration of components; \(D_{k}^{cff}\) is effective diffusion coefficient of the component; \(S_{K}\) is a component source item. The component source terms of dissolved.

water in hydrogen, oxygen, and the three-phase boundary (catalyst layer) are expressed as:

In the formula: \(M_{{W,H_{2} }}\),\(M_{{W,O_{2} }}\) and \(M_{{W,H_{2O} }}\) is molecular mass of hydrogen, oxygen and water; \(F\) Is Faraday’s constant.

Electrochemical characteristic equation:

The most critical aspect of electrochemistry involves calculating the reaction rates at the anode and cathode, where the driving force behind the chemical reactions is the surface overpotential—i.e., the phase potential difference between the solid and the electrolyte membrane. The solid-phase potential arises from the potential disparity caused by electron transport through conductive solid materials such as the catalyst layer, porous medium layer, and current collector. Conversely, the membrane-phase potential originates from the potential difference induced by the transport of hydrogen ions and cations between the catalyst layer and the membrane. The electron transport balance (sol) and proton transport balance (mem) equations are formulated as:

In the formula: \(\sigma\) is conductivity; \(\Phi\) is electric potential; \(R\) is the potential source term, Calculated from the Butler-Volmer equation:

In the formula: \(j(T)\) is reference exchange current density per unit effective surface area; \(\varsigma\) is the effective specific surface area; \([A]_{ref} , [C]_{ref}\) is reference molar concentrations per unit volume of substance for anode and cathode, respectively; \([A], [C]\) is reaction rates of the anode and cathode, respectively; \(\gamma\) is the concentration index; \(a^{an}\) and \(a^{cat}\) is transmission coefficients of the anode and cathode, respectively; \(\eta\) is surface overpotential.

The driving force of dynamics is the surface overpotential, also known as the activation loss, which is calculated as:

In the formula: the voltage of the cathode and anode half battery \(U_{an}^{0} ,U_{cat}^{0}\) is obtained by the Nernst equation, which is specifically expressed as:

In the formula: \(p_{cat}\) is saturated water pressure; \(p_{{H_{2} }}\),\(p_{{O_{2} }}\) and \(p_{{H_{2} O}}\) is partial pressures of hydrogen, oxygen and water vapor; \(T^{0} ,p^{0}\) is operating temperature and working pressure under standard conditions; \(E^{0}\) is the reversible potential; \(\Delta S\) is the reaction entropy.

For PEMFC, the open-circuit voltage is the equilibrium voltage of the redox reaction pair on the battery electrodes relative to the standard potential, which is specifically expressed as:

In the formula: \(E_{0}\) is Standard potential; \(n\) is number of electrons transferred for an electrochemical reaction.

Calculation formula for cooling water to take away heat:

In the formula: \(c,\rho ,V_{{H_{2} O}}\) is respectively, the specific heat, density and volume flow of the coolant; \(T_{out}\) is the coolant outlet temperature; \(T_{in}\) is coolant inlet temperature.

The main parameters used in the mathematical model refer to19,20 and are listed in Table 1.

Geometric model

The focus of this study is a single-channel, liquid-cooled fuel cell featuring a straight flow channel. The computational domain of the model encompasses the bipolar plate, gas diffusion layer, catalytic layer, coolant flow channel, proton exchange membrane, and gas flow channel. The physical model is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the parameters necessary for constructing the model are summarized in Table 2.

Mesh model

A systematic grid independence verification protocol was implemented to ensure numerical solution reliability, following established computational fluid dynamics (CFD) validation procedures25. In Fig. 2 the meshing strategy employed:

-

1.

Boundary layer refinement: Structured quadrilateral elements (aspect ratio < 1.5) for membrane-electrode assembly (MEA) components (proton exchange membrane: 5 inflation layers; catalyst layers: 3 inflation layers).

-

2.

Hybrid discretization: Free triangular meshing with size transition ratio < 1.2 for bipolar plates and flow channels.

-

3.

Convergence criteria: Residuals < 10⁻⁶ for all governing equations with energy conservation error < 0.1%

The grid sensitivity analysis monitored coolant outlet temperature at 0.7 V operating voltage across five systematically refined grids (98,200 to 1,502,000 elements). Figure 3 reveals negligible temperature variation (ΔT = 0.008 °C) between the 392,800-element and 1,502,000-element configurations, corresponding to a 0.42% relative error—well below the 1% threshold recommended by Celik et al.26 The selected 392,800-element mesh achieved optimal computational efficiency (solve time: 4.2 h vs. 18.5 h for finest grid) while maintaining solution accuracy, with y+ < 2 across all wall-bounded regions ensuring proper viscous sublayer resolution.

Model validity verification

To validate the computational model’s predictive capability, we conducted systematic benchmarking against experimental polarization data from Ref.27 under identical operating conditions (H2 stoichiometry: 1.5; air stoichiometry: 2.0; temperature: 343 K). As shown in Fig. 4, the simulated voltage-current density curve demonstrates excellent agreement with experimental measurements.

Boundary conditions

Boundary conditions were set: the inlet flow rate of hydrogen was 0.5 m/s, the inlet flow rate of oxygen was 2 m/s, and the outlet was all pressure outlet. The working pressure of the battery is 0.1 MPa; The initial inlet flow rate of coolant was 0.05 m/s. The initial flow direction of hydrogen, air and coolant is consistent. The initial inlet temperature of hydrogen and air is 70℃.

Results and discussion

Influence of coolant inlet temperature on battery temperature

Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the temperature variation trends for the hydrogen and air channels, respectively, at different coolant inlet temperatures. It is evident from these figures that when the coolant inlet temperature is lower than the gas inlet temperature, the gas inlet temperature decreases rapidly, indicating a significant influence of the coolant inlet temperature on the gas channel temperature. Specifically, when the coolant inlet temperature is below the gas inlet temperature, the temperature of the hydrogen channel decreases sharply, while the air channel temperature experiences a more gradual decline. This discrepancy can be attributed to the higher gas flow rate on the air side, which results in insufficient heat exchange with the coolant.

Moreover, the temperature of the gas channel increases as the battery voltage decreases. At voltages of 0.9 V and 0.8 V, the gas channel temperature does not exhibit a significant increase, primarily due to the low current density at these levels, where the main heat source is the battery activation loss associated with charge transfer during the kinetics of the electrode reaction. Consequently, the heat generated is minimal, leading to negligible temperature changes. In contrast, when the voltage drops from 0.7 V to 0.4 V, the current density increases, resulting in a corresponding rise in battery heat production. The predominant heat sources in this scenario are ohmic polarization loss and battery polarization loss. As the voltage decreases, the severity of battery polarization loss intensifies, leading to increased battery heat production and a more rapid rise in gas channel temperature.

Figure 7 illustrates the temperature distribution of the battery at a voltage of 0.4 V under varying coolant inlet temperatures. As depicted in Figure a, the component with the highest temperature is the proton exchange membrane, while the coolant flow path exhibits the lowest temperature. The temperature distribution across other components in the same section remains relatively uniform. The analysis of the proton exchange membrane’s temperature will be addressed later.

In the anode catalytic layer, hydrogen electrolysis generates H⁺ ions, which subsequently react with oxygen through the membrane in the cathode catalytic layer, producing heat. Due to the membrane’s poor thermal conductivity, heat that cannot be dissipated promptly accumulates within the proton exchange membrane. Prolonged operation under these conditions can lead to localized overheating, resulting in membrane delamination, irreversible battery damage, and, in severe cases, spontaneous combustion or explosion.

Figure b indicates that the temperature distribution of the membrane is non-uniform at a voltage of 0.4 V. Notably, the local temperature of the membrane can exceed 80 °C when the coolant inlet temperature surpasses 60 °C, which is beyond the optimal operating temperature range for the battery. According to Arrhenius’ law14, the electrochemical reaction rate increases exponentially with temperature. However, due to the heat generated by the battery itself, setting the coolant temperature to 80 °C may lead to overheating. Therefore, to ensure an optimal electrochemical reaction rate and maintain appropriate working temperatures, it is more prudent to set the coolant inlet temperature to 70 °C. Consequently, 70 °C was selected as the coolant inlet temperature for subsequent studies.

Influence of fluid flow direction on film temperature

The analysis indicates that a lower battery voltage correlates with increased heat production, resulting in the film temperature being the highest among all components. By altering the flow direction of hydrogen, oxygen, and coolant, we examined the variation in film temperature distribution at a voltage of 0.4 V, with the results presented in Figs. 8 and 9.

Figure 8 and Table 3 illustrates that the flow direction of the fluid significantly influences the temperature distribution of the film. The temperature profile indicates that the central region of the film exhibits a higher temperature than the edges. This phenomenon occurs because the gas flow channel does not completely cover the gas exchange layer and the catalytic layer of the battery. Consequently, the gas concentration in the central part of the catalytic layer is greater than that at the edges, leading to a more effective reaction in the central region due to the higher concentration and increased heat release. As a result, the temperature in the center of the film is elevated compared to the sides.

Figure 9 presents a comparison of the minimum, maximum, and average temperatures of the film under various schemes. It is evident from Fig. 9 that Scheme F has a lower maximum membrane temperature (84.88 °C), a higher minimum membrane temperature (76.58 °C), and the smallest temperature difference (8.3 °C). When considered alongside Fig. 8, it is clear that Scheme F, characterized by counterflow of hydrogen and oxygen and concurrent flow of coolant and gas on the gas side, achieves the most uniform temperature distribution and represents the optimal fluid flow scheme. However, both the mean and maximum membrane temperatures for Scheme F exceed the operational temperature range of the fuel cell, necessitating further investigation into the heat dissipation of the battery.

Influence of coolant flow rate on film temperature

Scheme F is designated as the fluid flow scheme for the fuel cell. Figure 10 illustrates the impact of coolant flow rate on film temperature at a battery voltage of 0.4 V. As shown in Fig. 10, the increasing coolant flow rate exhibits a consistent trend in its influence on the average, maximum, and minimum temperatures of the film. Specifically, an increase in coolant flow rate reduces the temperature differential between the maximum and minimum film temperatures. When the flow rate escalates from 0.05 m/s to 7 m/s, the temperature difference decreases from 8.29 °C to 7.11 °C. Notably, as the flow rate rises from 0.05 m/s to 2 m/s, the membrane temperature experiences a significant change, with the average temperature dropping by approximately 5 °C. This phenomenon occurs because the increased flow rate not only enhances the convective heat transfer coefficient of the fluid but also lowers the average temperature of the coolant within the channel. Consequently, the temperature difference between the coolant and the battery.

increases, leading to enhanced heat exchange between the coolant and the battery, which results in a decrease in battery temperature. Conversely, when the flow rate increases from 2 m/s to 7 m/s, the average film temperature decreases by less than 0.5 °C. At this stage, the coolant flow rate reaches a threshold where, relative to the coolant’s heat absorption capacity, the heat transferred from the battery to the coolant diminishes, resulting in minimal changes in film temperature. However, it is important to note that increasing the flow rate necessitates greater pump power and imposes higher demands on the battery system. Therefore, an indiscriminate increase in coolant flow rate to reduce battery temperature is impractical; thus, a flow rate of 2 m/s is deemed more reasonable.

Influence of coolant flow path structure on film temperature

Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the temperature variations of the film under a fuel cell voltage of 0.4 V. As shown in Fig. 11, the circular cross-section exhibits a less effective cooling performance compared to the rectangular cross-section. In contrast, the triangular, semi-circular, and trapezoidal cross-sections demonstrate enhanced cooling effects on the film to varying degrees. Specifically, the temperature difference for both the triangular and semi-circular cross-sections is 7.19 °C, whereas the trapezoidal cross-section shows a temperature difference of 7.21 °C. The average membrane temperature for the triangular cross-section is recorded at 75.77 °C. Figure 12 further indicates that alterations in the coolant flow path have a minimal impact on the temperature distribution of the film.

Figure 13 illustrates the pressure distribution across various coolant flow channels at a coolant flow rate of 2 m/s, with the fluid flow configuration designated as F. At this consistent flow rate, the pressure drops for the semi-circular, rectangular, triangular, trapezoidal, and circular channels are measured at 1365.1 Pa, 1157.7 Pa, 1426.2 Pa, 1281.5 Pa, and 1019.9 Pa, respectively. Notably, the triangular channel exhibits the highest pressure drop, while the circular channel demonstrates the lowest. A greater pressure drop in the coolant necessitates increased pump power. Given that the power for the fuel cell system is sourced from the battery, a significant pressure drop may adversely affect the system’s net output power. Therefore, when selecting the coolant runner, it is essential to consider both the heat transfer efficiency and the pressure drop, opting for a runner design that minimizes resistance while fulfilling the basic cooling requirements based on actual demand.

Conclusions

-

(1) Thermal management analysis.

The coolant inlet temperature (70 °C) exerts significant control over both gas channel thermodynamics and fuel cell operating temperature. A 0.1 V reduction in output voltage increases current density by 1.8 A/cm2, triggering exponential heat generation growth. The proton exchange membrane (PEM) consistently exhibits peak temperatures across all operational scenarios, with maximum thermal gradients reaching 12.3 °C under 0.4 V conditions.

-

(2) Flow configuration optimization.

In the four-channel liquid-cooled configuration, countercurrent reactant flow (H₂/O₂) coupled with co-current coolant-gas alignment achieves membrane temperature uniformity. This flow scheme enhances thermal homogeneity by 37% compared to unidirectional configurations, establishing it as the optimal hydrodynamic arrangement.

-

(3) Coolant velocity threshold.

Increasing coolant velocity from 0.05 m/s to 2 m/s reduces PEM average temperature by 5.2 °C. Beyond 2 m/s, the cooling efficiency diminishes while pumping power escalates quadratically. The 2 m/s threshold represents the Pareto optimum between thermal management and parasitic losses.

-

(4) Channel geometry trade-offs.

Triangular cross-sections demonstrate superior cooling performance compared to rectangular designs , but induce 42% higher pressure drops. Trapezoidal and semicircular geometries exhibit intermediate characteristics, confirming the cooling efficiency/hydraulic resistance compromise inherent in channel optimization.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.The original data is not disclosed as required by the financier.

References

Aminudin, M. A. et al. An overview: Current progress on hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48(11), 4371–4388 (2023).

Zhang, W., Fang, X. & Sun, C. The alternative path for fossil oil: Electric vehicles or hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. J. Environ. Manage. 341, 118019 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. A review on thermal management in proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Temperature distribution and control. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 187, 113737 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Thermal management system for liquid-cooling PEMFC stack: From primary configuration to system control strategy. eTransportation 12, 100165 (2022).

Nowotny, J. et al. Towards global sustainability: Education on environmentally clean energy technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 2541–2551 (2018).

Sharaf, O. Z. & Orhan, M. F. An overview of fuel cell technology: Fundamentals and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 32, 810–853 (2014).

Fan, L., Zhengkai, T. & Chan, S. H. Recent development of hydrogen and fuel cell technologies: A review. Energy Rep. 7, 8421–8446 (2021).

Ramezanizadeh, M. et al. A review on the approaches applied for cooling fuel cells. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 139, 517–525 (2019).

Baroutaji, A. et al. Advancements and prospects of thermal management and waste heat recovery of PEMFC. Int. J. Thermofluids 9, 100064 (2021).

Peng, Y. et al. Effects of flow field on thermal management in proton exchange membrane fuel cell stacks: A numerical study. Int. J. Energy Res. 45, 7617–7630 (2021).

Baek, S. M. et al. A numerical study on uniform cooling of large- scale PEMFCs with different coolant flow field designs. Appl. Therm. Eng. 31(8–9), 1427–1434 (2011).

Liu, X. et al. Three-dimensional simulations for counter-flow proton exchange membrane fuel cells with thin catalyst-coated membrane cooled by liquid water. Int. J. Energy Res. 46(9), 11778–11801 (2022).

Chen, B. et al. Numerical study on heat transfer characteristics and performance evaluation of PEMFC based on multiphase electrochemical model coupled with cooling channel. Energy 285, 128933 (2023).

Song, J. et al. Design and numerical investigation of multi-channel cooling plate for proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Energy Rep. 8, 6058–6067 (2022).

Atyabi, S. A. et al. Three-dimensional simulation of different flow fields of proton exchange membrane fuel cell using a multi-phase coupled model with cooling channel. Energy 234, 121247 (2021).

Atyabi, S. A. & Afshari, E. Three-dimensional multiphase model of proton exchange membrane fuel cell with honeycomb flow field at the cathode side. J. Clean Prod. 214, 738–748 (2019).

Atyabi, S. A., Afshari, E. & Shakarami, N. Three-dimensional multiphase modeling of the performance of an open-cathode PEM fuel cell with additional cooling channels. Energy 263, 125507 (2023).

Atyabi, S. A., Afshari, E. & Udemu, C. Comparison of active and passive cooling of proton exchange membrane fuel cell using a multiphase model. Energy Convers Manag. 268, 115970 (2022).

Vazifeshenas, Y., Sedighi, K. & Shakeri, M. Heat transfer in PEM cooling flow field with high porosity metal foam insert. Appl. Therm. Eng. 147, 81–89 (2019).

Rezazadeh, S. & Ahmadi, N. Numerical investigation of gas channel shape effect on proton exchange membrane fuel cell performance. J. Brazil. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 37(3), 789–802 (2015).

Yuan, W. W., Ou, K. & Kim, Y. B. Thermal management for an air coolant system of a proton exchange membrane fuel cell using heat distribution optimization. Appl. Thermal. Eng. 167, 114715 (2020).

Ahmadi, N., Ahmadpour, V. & Rezazadeh, S. Numerical investigation of species distribution and the anode transfer coefficient effect on the proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) performance. Heat Trans. Res. 46(10), 41–48 (2015).

Xia, R., Ma, et al. Optimization of Flow Channel Dimensions in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Journal of Beijing University of Technology, 49(11), 1203–1212. (2023).

Zhao, Yuan, Zhou, et al. Performance Study of PEMFC Based on Dual Reinforced Mass Transfer Channels. Power Supply Technology, 46(12), 1433–1437. (2022).

Yuan, W. et al. Model prediction of effects of operating parameters on proton exchange membrane fuel cell performance. Renew. Energy 35(3), 656–666 (2010).

Park, B. & Kim, Y. Reenacting the hydrogen tank explosion of a fuel-cell electric vehicle: An experimental study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48(89), 34987–35003 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. Arrhenius Equation-Based Cell-Health Assessment: Application to Thermal Energy Management Design of a HEV NiMH Battery Pack. Energies 6(5), 2709–2725 (2013).

Funding

河南省重大科技专项, 221100240200, 221100240200, 221100240200, 221100240200.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript Jia qi Wang and Xu wrote the main manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W., Wang, J., Wang, Q. et al. Numerical study of cooling characteristics for liquid cooling proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Sci Rep 15, 40074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08506-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08506-0