Abstract

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and its subtypes are serious concerns affecting a woman’s quality of life and pose a challenge for her social reintegration. Prolonged labor leading to trauma of the pelvic floor muscles during delivery, surgical or other trauma, aging and menopause, lifestyle changes, and genetic factors may contribute to the tissue degeneration and prolapse of pelvic organs. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the potential contributions of IGF-1 and LARP6 to the pathophysiology of poliomyelitis- dysplastic scoliosis and help in devising preventive and therapeutic measures. This study included a population of 15 women suffering from POP as a case group and a control group of 15 women who underwent total hysterectomy for benign gynecological diseases. Their vaginal wall tissue samples were obtained, and differences in expression of IGF-1, LARP6, Collagen I/III and MMP2 were analyzed using Western blot (WB), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and multiplex immunofluorescence (mIHC) techniques. Collagen deposition and other histopathological changes were examined by HE staining and Masson staining. Patients’ with POP’s vaginal wall tissues were used for isolating and culturing primary fibroblasts, which were then subjected to varying concentrations and time durations of IGF-1 treatment to optimize the culture conditions, measuring Collagen I and III expression levels as indicators. Changes in the expression levels of LARP6, collagen metabolism related proteins, and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway were investigated using WB and RT-qPCR, further analysis was done by applying PI3K/AKT signaling pathway inhibitors; CCK-8 and Tunnel histomorphology analysis were used to evaluate cell proliferation and apoptosis, respectively. Moreover, a LARP6 knockdown model was created whereby siRNAs specifically targeting the LARP6 transcript were transfected into cells, and subsequently, the protein and mRNA levels of collagen I, III, MMP2, and TIMP1 were analyzed by WB and RT-qPCR. LARP6 and IGF-1 expression was found to be significantly lower in the vaginal wall tissues of POP patients compared with controls. Histological staining revealed that collagen fiber structures in the POP group were loose, disorganized, and discontinuous. In primary fibroblasts, IGF-1 was able to up-regulate LARP6 and collagen expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner and favorable to the secretion of LARP6 and collagen through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. The knockdown of LARP6 by siRNA technology demonstrated significant reduction of collagen secretion expression suggesting interferences of LARP6 inhibits collagen synthesis in fibroblasts. IGF-1 has a strong correlation with LARP6 in relation to the development of POP. The reduction in fibroblasts in the subepithelial layer of the vaginal wall is probably associated with POP, while depletion of collagen synthesis and escalation of collagen breakdown may serve as the pathophysiologic foundation for POP. In patients suffering from POP, IGF-1 has the capability to enhance the expression of LARP6 and collagen in their fibroblasts, which highly depends on the activity of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. This study unveils new insights and possible molecular approaches to the pathophysiology of POP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) is a common gynecological condition caused by the displacement and damage of pelvic organs, severely impairing the health of women around the globe1. Due to the gradual increase in the elderly population, the populace suffering from POP has shown an increase leading to newer public health problems in contemporary society. The clinical consequences of POP varies from asymptomatic to organ prolapse that can be severe enough to cause urovaginal bleeding and inflammation2. While, it is well understood that with the advancement in medicine life can be prolonged, managing quality of life becomes a vital crucial challenge pop has shown to deeply impact3,4.

POP’s pathogenesis is complicated and has many interacting factors, particularly molecular level changes in connective tissue. In patients with POP, fibroblast activity is diminished, resulting in impaired collagen metabolism that compromises the structural and mechanical properties of the tissues5. Pelvic connective tissue forms the extracellular matrix (ECM) of collagen and elastin fibers, which are primary constituents of the ECM, and are crucial for the maintenance of tissue structure and function6. Other significant constituents of the extracellular matrix are fibronectin, fibrinogen, hyaluronic acid, laminin, and integrins, which are linked to the membrane of the cell and facilitate the cell adhesion process7. Integrins are of fundamental importance in the metabolism of ECM proteins and in biological cell replacement which is a constant process8. A major player in collagen metabolism and extracellular matrix cleanse is fibroblast.

Types I and III collagen are crucial for the strength of the pelvic floor tissues. The pelvic floor connective tissue collagen is produced by fibroblasts which, after being secreted into the intercellular matrix, can be degraded by Metalloproteinase (MMP) synthesized by fibroblasts. If the function or number of fibroblasts declines, and if there is an increase in MMP expression, this leads to a decrease in collagen. As a result, there is a frail pelvic floor organ supporting fibroelastic tissue which cannot maintain the pelvic organs and tissues, leading to prolapse5.

Structurally, the most predominant protein among all vertebrates is Type I collagen, which also happens to have the slowest rate of synthesis due to possessing a long protein half-life of 60–70 days. Type I collagen synthesis has the potential to increase several hundred times during reparative or reactive fibrosis. This massive upregulation is achieved through several regulatory mechanisms9. Within this context, post-transcriptional regulation is primary and includes mRNA processing, transport, stabilization, and translation which is done by proteins called RNA-binding proteins. Out of all the numerous RNA-binding proteins, the only one that has been found to control Type I collagen synthesis is La ribonucleoprotein structural domain family member 6 (LARP6)9.

Research have indicated that LARP6 is crucial to the biosynthesis of type I collagen in human lung fibroblasts and other cell types10. Most LARP6-expressing cells are fibroblasts, and keloid fibroblasts express LARP6 more than normal skin and proliferative scarring fibroblasts11. LARP6 post-translational modification includes phosphorylation of Ser451 chiefly by the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and AKT blockade diminishes type I collagen secretion12. Therefore, LARP6 is a critical factor in collagen metabolism. Disordered collagen metabolism indeed may cause directly the structural and functional alterations in the pelvic floor tissue that leads to descensus. Considering LARP6’s putative capability to modulate collagen metabolism, we proposed a working hypothesis that LARP6 is a contributory factor in the pathology of POP.

Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) is classified as a mitogen and an inhibitor apoptosis13which is involved in a wide variety of physiological processes like tissue14muscle growth, as well as bone and cartilage healing15. IGF-1 also promotes the secretion of extracellular matrix molecules such as poly-glycoproteins and collagen type I (COLI)16 by fibroblasts. IGF-1 binds to the cell membrane IGF-1 receptor initiating self-phosphorylation of the IGF-1 receptor, activating insulin receptor substrate-1 and the downstream PI3K/AKT pathway16. Evidence suggests that IGF-1 promotes collagen fibrillogenic through LARP6, thus proposing LARP6 as an important mediator of type I collagen synthesis in vascular smooth muscle13. In primary mouse cranial preosteoblasts, IGF-1 post- transcriptionally upregulates LARP6 and promotes COL1A2 expression along with osteoblast differentiation17.

While much is known about the roles of IGF-1 and LARP6 in different physiological functions and processes, their associations with POP remain unresolved. The objectives of this study were to examine IGF-1 and LARP6 concerning POP, explore their molecular mechanisms, and widen the horizons regarding the etiology of POP, as well as pave the way towards establishing novel approaches for the predictive and corrective intervention.

Materials and methods

Participants and specimen collection

This investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baiqun Hospital located in Shanxi Province of China. Thirty patients who had surgical procedures performed at Baiqiu’en Hospital in Shanxi Province were included. These encompassed 15 patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in the case group, and 15 patients in the control group presenting for total abdominal hysterectomy for benign lesions of the uterus.

The patients in the control group had a total abdominal hysterectomy due to benign gynecological conditions. All patients in the POP group had previously undergone a vaginal delivery, and the selected control group had some patients who had completed childbirth, but did not have prolapse. This was done to ensure that both groups had experienced childbirth and to investigate other possible causes of POP apart from vaginal delivery. While women who are multiparous or those without POP may be adequate controls, they were excluded for ethical and logistical reasons of healthy subjects’ vaginal wall biopsy procurement.

Participants in the POP group were stratified as having stage III-IV prolapse according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system. The following exclusion criteria were established:

-

i.

Acute exacerbation of chronic pelvic inflammatory disease.

-

ii.

Endometriosis or adenomyosis, either of which qualifies on the basis of past medical history.

-

iii.

Any history of cancer, PF surgery, or other forms of connective tissue disorder.

-

iv.

Estrogen treatment in the three months leading up to the surgery.

-

v.

Smoking history in any of the study subjects.

With the patient under appropriate aseptic conditions, all tissues of the vaginal wall approximately one cubic centimeter in dimension at the anterior vaginal wall close to the dome were scrubbed with saline during the operation. These surgical specimens were treated as follows:

-

i.

Histological Studies: Some specimens were fixed in 10% formalin for 48 h and then completely processed into paraffin blocks.

-

ii.

Molecular and Biochemical Research: Other specimens were refrigerated at -80 degrees centigrade after being wrapped in aluminum foil and transported in ice boxes for further molecular biological and biochemical analysis.

-

iii.

Fibroblast Culture: Some of these samples were placed into DMEM/F12 culture medium with 3% antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and then immediately aliquoted into the intercellular compartment for primary fibroblast culture.

Histological examination

The specimens were first preserved in 10% formalin before being dehydrated by an alcohol gradient. After being cleared by xylene, the specimens were wax dipped, embedded, and sectioned. The sections underwent preparation were subsequently stained with H&E to evaluate the tissue morphology, and stained with Masson’s trichrome to assess the collagen fiber distribution. The processed specimens were used for a light microscope examination for their histopathological analysis.

Immunochemistry (IHC)

Sections were dewaxed with water and treated with hydrogen peroxide to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity. Antigen retrieval was performed, followed by incubation with primary and secondary antibodies. They were color developed with diaminobenzidine (DAB), stained with hematoxylin, then underwent differentiation, bluing, dehydration, clearing, and mounting. Negative control reagents for primary and secondary antibody were Phosphate buffer solution (PBS). The following were the relevant antibodies:

-

i.

collagen type I (COL1) antibody (1/100, CY5120, Abways),

-

ii.

collagen type III (COL3) antibody (1/1000, 22734-1-AP, Proteintech),

-

iii.

IGF-1antibody (1/200, 28530-1-AP, Proteintech),

-

iv.

LARP6 antibody (1/200, bs-17105R, BIOSS),

-

v.

MMP2 antibody (1/100, CY5189, Abways).

Multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC)

Target protein labelling was executed utilizing the TSA Fluorescence Kit (Melady®Biosciences) following the outlined procedures from the manufacturer. Sections were dewaxed and hydrated; heat induced antigen repair was done. Primary antibodies were followed by secondary antibodies with washes in PBS in between. The sections were incubated with suitable dyes used for TSA staining. In this step, the same primary antibodies used for conventional IHC were applied. After TSA staining was completed with the first antibody, the procedure was repeated with the second antibody. After all target staining was completed, the sections were washed with PBS and DAPI was used for restaining. The sections were then mounted with the required mounting media and whole slide scanned using a multichannel fluorescence scanner (3DHISTECH, Pannoramic MIDI) for imaging. The images were scanned and analyzed using SlideViewer software.

Western blot analysis

Total protein extraction

The collected tissues were precisely weighed, sheared, and ground before being homogenized in a lysis buffer solution (RIPA: PMSF 100:1). The BCA Protein Assay Kit was used to determine the protein concentration. The lysates were mixed with 5× protein sampling buffer prior to being denatured and stored at -80 °C for further analysis.

For the cell samples, the culture medium was aspirated and the cells were washed with PBS. Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer containing both protease and phosphatase inhibitors on the ice for 30 min. The lysate was collected via scraping and sonication, before being mixed with 5× protein uploading buffer, denatured, and stored at -80 °C.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

SDS-PAGE was performed to isolate protein samples. To begin, a separation gel was poured into the gel plate, with the concentrated gel placed on top. After it solidified, I conducted electrophoresis at 80 V for 30 min, and 120 V for 90 min in order to carry out proper protein separation.

Proteins were then loaded onto a PVDF membrane at 300 mA for 2.5 h. The membrane was incubated in 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1 h in order to block non-specific binding sites. Once washed with 1×TBST to remove excess blocking reagent after 1×TBST, non-specific binding methods were no longer applicable.

Antibody incubation and detection

The membrane was prepared for the experiment by incubating at 4 °C overnight with the primary antibodies designated for target proteins. Following subsequent washing steps with 1xTBST (5 min per wash), the membrane was incubated with tertiary antibodies for 2 h at 4 °C. Additional washes with 1×TBST of 10 min were undertaken to ensure that no free antibodies remained bound. The imaging outcomes of the protein bands were captured and set aside for later interpretation, after being exposed to a light-sensitive photographic plate and imaged using photoluminescence capture.

The following antibodies were used: LARP6 antibody (1/1000, CQA4919, Cohesion), IGF-1 antibody (1/1000, 28530-1-AP, Proteintech), COL1 antibody (1/1000, CY5120, Abways), COL3 antibody (1/1000, 22734-1-AP, Proteintech), MMP2 antibody (1/1000, CY5189, Abways), TIMP1 (1/1000, CY6616, Abways), p-PI3K (1/1000, CY6427, Abways), PI3K (1/1000, CY5322, Abways), p-AKT (1/1000, CY6016, Abways), AKT (1/1000, CY5561, Abways). For internal controls, β-Actin (1:5000, AB2001, Abways) and GAPDH (1:5000, AB2000, Abways) were used.

Primary fibroblast culture and identification

Primary Human Vaginal Fibroblasts (hVFs) were procured from Pop patient’s fresh vaginal wall tissue. Under sterile conditions, the tissues were mechanically cut into small pieces, followed by enzymatic digestion using 1% type I Collagenase (C9722, Sigma) in a 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator for two hours, followed by trypsin digestion for 30 min. After the enzymatic digestion, the suspension was passed through a 100 μm filter to remove undigested tissue and transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

Following filtration, the suspension underwent centrifugation, and the resultant supernatant was removed. The pellet underwent resuspension within 2% double antibody solution in PBS, followed by a second centrifugation and subsequent removal of the supernatant. The remaining cells were suspended in DMEM/F12 medium with 15% fetal bovine serum (AUS-01 S-02, Cell-Box) and placed at 37 °C within a 5% CO₂ incubator. Cell expansion was allowed until confluence was achieved. For monitoring of cell identity, the second-passage cells were utilized.

Using antibodies Vimentin (CY5134, Abways) and Cytokeratin 19 (CY5312, Abways), hVFs were characterized by immunostaining. For following experiments, cells from passages 3 to 7 were utilized. For further investigations, recombinant human insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) protein was purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE).

Cell freezing and recovery

PBS was used to wash the harvested cells in stable condition twice, before they placed into an incubator for five minutes. They were then digested with 0.125% trypsin for the next two minutes. After trypsin was added, a digestion medium was added which was rich in nutrients, followed by a centrifuge to gather the cell pellet. The supernatant was removed before collection, after which the cells were resuspended in 1 mL of freezing solution. For long-term storage of the samples, the suspension was blended, collected in a freezing tube, and placed in a -80 °C tank.

Inhibitors suppress PI3K and AKT cell signaling pathways

The fibroblasts undergoing logarithmic phase growth were trypsinized and evenly distributed in 6 well plates. Cells were allowed to attach to the surface of the plate, after which the culture medium was changed and supplemented. Following an incubation period, total protein and RNA was extracted for further analysis by Western blot and RT-qPCR.

Extraction of total RNA and RT-qPCR detection

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol Total RNA Extraction Kit. For cDNA synthesis, total RNA was 1 µg for template and was treated with First-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit in accordance with the manufacturer instructions. Then cDNA was subjected to qPCR with commercially integrated qPCR kit. Relative expression values of target genes were calculated through the 2−ΔΔCt method. To maintain the quality of RNA, all possible measures were taken during the procedure, such as performing reactions on ice and shielding from light. Each primer was written in Table 1.

Cell proliferation assay

Fibroblasts from the logarithmic growth phase were digested and washed for quantification with haematocrit plates. 100 µL of cell suspension was seeded per well in a 96-well plate with three replicate wells for each group. PBS was added to the edge wells for plate seeding at 3000 cells per well to minimize evaporation. Once the cells settled to the bottom, the corresponding drugs were dosed based on the experimental groups. The plates were then cultured under standard conditions and cell viability measured with CCK-8 assay at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h.

Apoptosis assay

The prepared fibroblasts were detached from the culture vessel and washed, then counted using a haematocrit plate. Each well of a 96-well plate was supplemented with 10,000 cells and three replicate wells were used for each group. Once the cells settled to the bottom of the plate, drugs were administered corresponding to the cell plate’s experimental grouping. The plates were incubated under standard culture conditions for 24 h after which the cells were evaluated for apoptosis using TUNEL assay.

Transfection of SiRNA from fibroblasts

Cells were seeded in a suitable volume of growth media without antibiotics one day prior to transfection. Subsequently, DNA and RNAi constructs were diluted in separate syringes in Opti-MEM I medium, which is serum-free, and mixed gently. Lipofectamine 2000 was mixed vigorously before use; a set volume was diluted into serum-free Opti-MEM I medium and kept at room temperature for 5 min. Lipofectamine was then mixed with the DNA/RNAi solution that had previously been prepared. After shaking gently, the resulting mixture was placed at room temperature for 20 min. With the pre-warmed transfection mixture, each well containing cells and media was added to in turn and gently swirled with the culture plate to mix. The cells were harvested after 48 h, which served as incubation time at 37 °C in a CO₂ incubator, for subsequent analysis. Western blots and RT-qPCR tests were performed as indicated earlier.

Statistical analysis

The data was scrutinized and analyzed with SPSS 26.0, while the graphs were made with GraphPad Prism 9.1. The measurements were presented as mean ± standard deviation. In order to strengthen the statistical analysis, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the most important variables in order to determine how precise the estimates were. Normality of the distribution was measured with Shapiro-Wilk (for small sample sizes, n < 50), followed by the examination of Q-Q plot visually. The results showed that all experimental data passed Pitot for normal distribution and did not exceed grade > 0.05, thus could pass t-test. An independent sample t-test was used for intergroup comparisons. Had the data been non-normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U test would have been used instead. Categorical data was presented in absolute numbers and percentages and differences were tested using chi square or Fisher’s exact test. For intergroup comparison, one-way analysis of variance (or one-way ANOVA) was used on the normally distributed data and the Kruskal-Wallis test for the other. Statistically significant results were considered to be those where P value was lower than 0.05.

Results

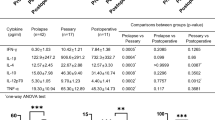

Comparison of the general data between the two patient groups

The baseline characteristics of the study population did not differ significantly between the POP and control groups which helps in comparison (Table 2). The Shapiro-Wilk test determined the normality of the data distribution (P > 0.05 for all variables), and this was also confirmed by Q-Q plots. So, for group comparisons, parametric tests were used. There was no statistically significant difference in age, pregnancy time, parity, and body mass index (BMI) of the two groups (P > 0.05). Inclusion of 95% confidence intervals supports these findings being robust since all intervals containing zero confirms no significant difference. These findings indicate that the demographic factors does not account on the molecular differences observed in the vaginal wall tissues. Moreover, none of the studied patients were either smokers or were in hormonal therapy three months before the surgery which guarantees these variables did not affect the results.

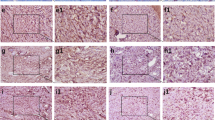

Histomorphological features of the vaginal wall observed by HE and Masson staining

The examination of histology shows that POP tissues had poorly organized collagen fibers that were fragmented compared to the dense and well-organized fibrillar structure observed in the controls (Fig. 1). These results indicate tissue damage and structural degeneration of the vaginal connective tissue in POP, which could hinder its mechanical support function.

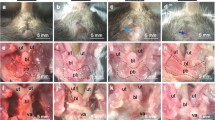

Expression of LARP6, IGF-1, COL1, COL3, MMP2 in vaginal wall tissues of the POP group and control group

LARP6 was predominantly found in the nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas IGF-I was found predominantly at the cell membrane. COL1, COL3, and MMP2, on the other hand, were mostly located in the interstitial compartment. LARP6, IGF-1, COL1, and COL3 expression in the vaginal wall tissue of POP subjects was diminished compared to the control group, whereas MMP2 expression was found to be elevated in the POP group compared to the control group (see Figs. 2, 3 and 4). These findings indicates reduction in collagen synthesis and elevation in ECM degradation in POP condition.

Culture and identification of primary fibroblasts

Fibroblasts derived from the anterior vaginal wall of POP patients possessed a characteristic spindle-shaped morphology. Their identity as a fibroblast was substantiated through immunocytochemistry as they were positive for waveform protein while being negative for keratin staining (Fig. 5). These observations confirm that primary vaginal fibroblasts have been successfully isolated for additional functional analyses.

IGF-1 promotes secretion of LARP6 and COL1 and COL3 from vaginal wall fibroblasts

To investigate how IGF-1 might influence POP collagen metabolism, we obtained primary fibroblasts from human vaginal anterior wall tissues and treated them with IGF-1 at 0, 20, 50, and 100 ng/ml and 0–48 h (0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h) serum free DMEM/F12 medium (control with 0 ng/ml IGF-1). The time and dose parameters were previously established from studies that showed IGF-1’s time and dose related influence on fibroblast proliferation and collagen production12,13. Subsequent analyses verified these conditions in preliminary experiments that sought to establish stimulation parameter optimization. With prolonged culture time, IGF-1 stimulated both COL1 and COLL3 expression in primary fibroblasts in a dose dependent fashion. With 36 h stimulation for the 100 ng/ml IGF-1, the expression trend for both COL1 and COL3 was maximized (Figs. 6 and 7). These results signify the stimulating effect of IGF-1 on fibroblast collagen production.

Human foreskin fibroblasts were treated with IGF-1 at 100 ng/ml for 36 h. Comparison of protein and mRNA expression levels of LARP6, p-PI3K, p-AKT, COL1, COL3, and TIMP1 in the treated vs. control group (serum free medium, 0 ng/ml IGF-1) showed the treated group had higher levels for every factor except MMP2 which was significantly lower in the treated group (P < 0.05). There were no significant changes in expression levels of PI3K and AKT. Co-expression levels of COL1 and COL3 showed an increase (Figs. 8 and 9). These results suggest that IGF-1 aids in the remodeling of the ECM by increasing collagen preservation and decreasing its degradation.

IGF-1 regulates LARP6 and collagen secretion by promoting the PI3K/Akt pathway

In the study, it was shown that collagen- and LARP6-synthesis due to the influence of IGF-1 was PI3K/AKT dependent. As shown in Figs. 10 and 11, both p-AKT and LARP6, COL1, and COL3 levels were lower in the 10µM AKT inhibitor treatment group when compared to the 5µM group. Levels of AKT did not differ significantly between groups. Clearly, the PI3K/AKT pathway is indispensable to the pathway for IGF-1–dependent collagen synthesis and ECM remodeling in POP.

For showing function of the PI3K/AKT pathway, example phosphorylation assays are not necessary to demonstrate what is involved without prior evidence of it operating. Specific pathway inhibitors serve a more direct functional proof by actively blocking the PI3K or AKT and evaluating the biological actions that follows. Inhibitor based analysis facilitates functional proof of involvement of these pathways by looking at proliferation, apoptosis and collagen secretion in cells. The control of gene expression and analysis of effector molecules bring other forms of proof add supplementary information for pathway involvement. These methods are helpful in understanding the mechanistic detail behind the problem as well as getting around the problem of missing phosphorylation being detected due to its low level or some random variation. While non-direct biochemical confirmation of the activation of the pathway relies on phosphorylation, proof on functionality of the pathway comes with much stronger detail without any dimension when dealing with non-phosphorylation logic.

The expression of COL1, COL3, and LARP6 in the IGF-1 treatment group was significantly greater than that of the control group. In the group with 10 µM AKT inhibitor, COL1, COL3, and LARP6 expression was significantly lower than the control group. There was no significant difference in the expression of COL1, COL3, and LARP6 in the IGF-1 + 10 µM AKT inhibitor group compared to the control group. Therefore, the PI3K/AKT pathway is proposed to mediate the effect of IGF-1 on the regulation of LARP6 and collagen expression in fibroblasts (Figs. 12 and 13). Since collagen is the main structural protein that forms the scaffold of the ECM, this evidence suggests that the lack of collagen in the tissues of Prolapse Of Pelvis (POP) is due to dysfunctional signaling through the IGF-1/PI3K/AKT pathway, thus, diminishing support to the vaginal wall which leads to further aggravation of prolapse.

Increased IGF-1 promotes fibroblast proliferation

The CCK-8 method showed variations in fibroblast proliferation after the application of 100 ng/ml of IGF-1 was used to treat fibroblasts for 36 h. IGF-1 treated groups showed greater proliferative activity in contrast to the control group, and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). (Refer to Fig. 14). This suggests that IGF-1 has a possible function in ECM sustenance and tissue healing in POP.

The analysis of Table 3 suggests that for Days 1 and 2, the confidence intervals include 0, meaning that there is no statistically significant difference between IGF-1 and Control groups, indicating that IGF-1 does not have much impact on cell viability during the early phase. Nevertheless, from Day 3 later, the confidence intervals are negative and do not include 0, supporting that IGF-1 does improve fibroblast viability compared to the Control group. Over time, the difference in magnitude suggests a stepwise improvement of IGF-1 effects. The observers difference by Day 5 which had the greatest amount of difference where the confidence interval range is widest, which suggests the strongest effect. The pattern shown would suggest that IGF-1 impacts cumulatively or for an extended period once cell proliferation is initiated. Biologically, during early phase (Days 1 and 2), IGF-1 is unlikely to be effective as there could be a delay in cell responsiveness. Mid-phase (Days 3 and 4), there is evidence of significant IGF-1 mediated cell viability due to increased fibroblast and metabolic activity. Late phase (Day 5), this effect is much more profound suggesting important signaling mechanisms that regulate mitosis and extracellular matrix remodeling remains active for long time. In summary, IGF-1 shows dramatic increases in fibroblast viability from Day 3 and the strongest impact at Days 4 and 5. Its impact at earlier time points is minor, suggesting the effect of IGF-1 stimulation is on a cellular timescale.

Increased IGF-1 inhibits apoptosis in fibroblasts

IGF-1 group showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in survival, compared with the control group. (See Fig. 15) This indicates that it may help in preserving ECM integrity in POP tissues, and suggests a protective role in fibroblast survival.

Decreased collagen secretion by fibroblasts after construction of a LARP6 knockdown fibroblast model

After LARP6 knockdown, we analyzed the levels of COL1, COL3, TIMP1, and MMP2 using Western Blot and RT-qPCR. We observed that COL1, COL3, and TIMP1 expressions were significantly down-regulated while MMP2 was significantly up-regulated in si1, si2, and si3 treated cases in comparison to the NC group. (Figures 16 and 17). Importantly, COL1 was reduced more than COL3, indicating that COL1 is more prone to undergo sensitivity in response to LARP6 depletion resulting in decreased COL1/COL3 ratio. This implies that LARP6 has a main role in synthesizing COL1, but when LARP6 is removed, there are also impacts on COL3 levels because there is some effect on the fibroblast collagen metabolism in which the fibroblasts lose collagen. That shows the importance of LARP6 as a controller of collagen subtypes which disrupts collagen metabolism and undermines the stability of extracellular matrix (ECM).

Discussion

Considering the pathomechanisms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), we consider the pathologic process while noting the importance of the pelvic floor fascia and ligaments as the major supportive soft tissues that sustain the normal posture of the pelvic organs. The most important constituent of these fabrics are the constituent cells termed as fibroblasts together with the collagen and elastin enriched extracellular matrix (ECM) which they secreted and which indeed form the bulk of the ECM and give structural support and elasticity required to pelvis floor18. The vaginal wall is made up predominantly of fibroblast cells and any alteration in their activity has a direct influence on collagen metabolism which directly influences the mechanical characteristics of the tissue5,6,19.

Still, it does remain vague whether these ECM changes are causing POP or are rather the result from imbalanced mechanical strain. Normally it is believed that the starting event of POP is ligament injury linked with vaginal delivery which tears down the supporting elements of the pelvic organs. Fracture of the vaginal wall is more probable to be an outcome rather than a primary start and is the result of more effective displacement of stress and changed ECM structures after ligament tearing. Our results illustrate pronounced collagen breakdown and altered functioning of fibroblasts in the wall tissues of vagina from patients with prolapse, but the relationship of these alterations with the development of prolapse is still unknown. Further research will focus on distinguishing the primary structural pathologies and those that developed due to weakened pelvic floor.

Genetic factors and mechanical factors can incur acquired defects which subsequently may result in functional differences in fibroblast cells of prolapsed tissue. This, in turn, affects collagen content for POP20,21. With collagen being the main component of connective tissue, it makes up 80% of the pelvic floor tissue, of which collagen types I and III are the most dominant and dictate the strength and elasticity of the tissue22. In this research, it was observed that patients suffering from prolapsed had reduced collagen content overall, in addition to reduced COL1 to COL3 ratios compared to non-prolapsed patients (Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13). Their histological staining showed that the collagen fiber network in the tissues forming the vaginal wall of patients with POP was loose, fragmented, and highly suggestive of ECM degradation. In addition, in vitro experiments showed that treatment with IGF-1 increased collagen expression in fibroblasts and raised the COL1/COL3 ratio, which indicates that IGF-1 has a role in collagen homeostasis. Notwithstanding, the effect of IGF-1 on the vaginal wall tissues of women suffering from POP is still to be investigated, considering the fact that while stimulation from IGF-1 may increase the COL1/COL3 ratio in vitro. Taking into account the in vivo remodeling of ECM, further research is required to determine whether an insufficiency in IGF-1 is an underlying factor in the altered COL1/COL3 ratio in tissues from POP. Further studies will need to address the question of whether restoration of collagen homeostasis and ECM integrity in POP is possible through IGF-1 supplementation using functional assays with fibroblasts from patients or through in vivo models.

Also, POP23 represents the culmination point of Abnormal and Disorganized Collagen Fibers In the disorganization, MMPs and TIMPs are known as the master modifiers of degradation within the ECM of the POP tissues, which undergo quantitative alterations that foster the fragmentation of collagen fibers24,25,26.

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is a peptide hormone which participates in skeletal and cartilaginous tissues healing, as well as tendon and skin tissues’ proliferation and repair. Its physiological activity is complex and includes the secretion of insulin-like growth factor (IGF), which begins healing of tissue17. Through the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, IGF-1 increases the secretion of ECM components: polysaccharide proteins and collagen I (COL1) by fibroblasts15. Our findings suggest, and prior studies support, that IGF-1 increases type I collagen synthesis and collagen fiber production via the downstream LARP6 (a member of the La family)-dependent mechanism signaled by the PI3K/AKT pathway16 (Figs. 10, 11, 12 and 13).

The functional studies utilizing pathway-specific inhibitors, which disengage the activity of the pathway and cause appropriate changes in the cellular responses, corroborate the importance of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Such approaches offer direct proof for the participation of the pathways, in this case, the proof being that these pathways are needed for the effects which IGF-1 brings about. Besides validation through inhibitors, validation is also achieved through expression analysis of the genes where the putative control of the pathway was shown to change under certain experimental conditions having the alteration of PI3K/AKT-associated genes turned on or off. These supplementary techniques provide a greater understanding of the participation of the pathways.

Although phosphorylation assays can act as a molecular marker for pathway activation, they do not measure permanent pathway activity and instead measure only spatially and temporarily local-ordered-transitioned phosphorylated states. Because of the time dependent nature of events that cause phosphorylation, cell cycle progression functional tests give a broader view of the active pathway. Further functional analyses based on phosphorylation where signal transduction mediated by PI3K/AKT is dissected could be performed in order to deepen the understanding of the mechanistic clues and will be planned for further studies about complete description of the activation of the pathways.

We found no references in the available literature that discussed if the IGF-1 induced effects are reversible following a cessation period. In our research, we incorporated primary fibroblasts, which exist within a determinate timeframe and eventually undergo senescence. Because of these self-imposed limits, we did not witness reversibility within the study frame. Hence, it was omitted from the results section.

LARP6 is an RNA binding protein that not only enhances collagen synthesis in fibroblasts but also stimulates proliferation and invasion of tumor cells. It has been reported that LARP6 expression can be upregulated by IGF-1 via a post-transcriptional mechanism that also leads to COL1 expression and osteoblast differentiation13. Our data validated the fact that collagen expression was severely diminished in fibroblasts harvested from POP patients with a LARP6 knockdown model, further proving the central role of LARP6 in collagen metabolism. (Figures 16 and 17). While LARP6 is known to be the primary factor regulating type I collagen (COL1), here we report that knockdown of LARP6 also decreased expression of COL3. This implicates that COL3 expression might be controlled by COL1 expression in a more indirect manner, possibly involving some common transcription or remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Furthermore, LARP6 depletion resulted in lower ratio of COL1/COL3 despite the reduction of both collagen types, which suggests the regulatory effect of LARP6 on COL1 is more profound than that of COL3. This disruption might result in deterioration of ECM structural integrity, which highlights the importance of LARP6 in collagen homeostasis. Further investigations should be conducted to understand how LARP6 impacts balance of collagen and stability of ECM in fibroblasts.

Considering that both collagen inadequacies and ECM remodeling deficiencies play a role in the pathophysiology of POP, new non-surgical approaches that focus on fibroblast activation and collagen production have emerged. These include laser technologies, particularly diode lasers and CO₂ fractional lasers, which have been shown to significantly stimulate fibroblast activity, improve ECM remodeling, and enhance collagen deposition27,28. Strikingly, in our research, we uncovered what we term the IGF-1 → LARP6 → collagen regulatory circuit as a prominent pathway in collagen metabolism which leads to the proposition that laser therapy may, at least in part, operate by activating IGF-1 signaling.

A significant merit of this investigation is that all examined subjects did not have any history of smoking or recent usage of hormonal therapy. This assisted in avoiding any masking effects, which increases the dependability of our results further. Our research adds important knowledge about the contribution of IGF-1 and LARP6 in the pathogenesis of POP. However, some shortcomings need to be pointed out.

First, this analysis concentrated on how the LARP6 knockdown affected collagen metabolism. It is still unknown whether these effects can be rescued by IGF-1. Considering that IGF-1 alters collagen synthesis and degradation by means of pathways like PI3K/AKT, it is likely that IGF-1 is capable of partially restoring the effects of LARP6 depletion through different means other than LARP6. Nonetheless, the interplay of IGF-1 and LARP6 in collagen homeostasis remains to be elucidated. Further studies should incorporate attempts to rescue the LARP6-deficient fibroblasts with IGF-1 to ascertain if supplementation of this factor would aid in restoring collagen synthesis and ECM remodeling to equilibrium. Elucidation of these mechanisms would represent another step toward understanding the intricate network regulating collagen metabolism, as well as contribute to targeting therapy for POP and other disorders of connective tissues.

Second, The sample size was also small (n = 15 per group) which may lead to reduced statistical power and generalizability. This study’s limitation is the absent documentation of menopausal status, which could affect collagen metabolism and tissue remodeling. Future studies would need to evaluate menopausal status to better understand its role in POP pathogenesis in consideration. Also, all participants were drawn from one medical facility which can result in selection bias. It is important to conduct larger, multicenter studies with more representative patient populations in order to verify our results and broaden their relevance to other POP patients.

Third, this study was performed in vitro with primary vaginal fibroblasts which, while clinically relevant, cannot simulate the entirety of the in vivo environment. The absence of animal models or patient derived xenografts hinders our capacity to evaluate the ramifications of IGF − 1/LARP6 signaling on ECM remodeling and the progression of POP over time. Other in vivo models should be used for further research to confirm these molecular mechanisms in a living organism.

Fourth, while our study concentrated on fibroblast-mediated collagen Synthesis, POP is a multicausal problem with aetiological components from hormonal shifts, mechanical forces, and hereditary factors. Laparoscopic sterilization contributes to collagen loss, however, its crosstalk with IGF-1/LARP6 signaling is not known. Similarly, mechanical loading causes changes to the ECM, and its effect on IGF-1 dependent fibroblast activity should be studied more closely. Also, other important constituents of the ECM like elastin, fibronectin and MMPs may interact with IGF-1/LARP6 signaling, which calls for more extensive research.

Lastly, while considering potential therapeutic targets, our results underscore IGF-1 and LARP6 modulators. However, their clinical use remains unsupported. There is no data on the best route of administration (for example, local injection or systemic), long-term safety, and efficacy. Moreover, evaluating off-target effects and dose optimization require great scrutiny. Further research needs to be done focused on the possibility of combining already existing treatment modalities, like laser treatment or estrogen replacement, with IGF-1 based therapies in order to formulate effective, less invasive treatment approaches for POP management.

Even though this conclusion has some limitations, it provides a sound molecular rationale that can aid in future preclinical and clinical research for novel therapeutic approaches POP treatment.

Further research efforts need to determine if laser therapies increase IGF-1 expression and PI3K/AKT signaling, and if these events lead to increased LARP6-dependent collagen production in vaginal fibroblasts from women with POP. If this hypothesis is correct, then the fusion of laser therapy with IGF-1 therapy may be a novel means to enhance the integrity of the ECM and the support tissues for the vaginal wall in patients with POP. Such an approach may be less invasive and more beneficial than conventional surgical repairs, especially for patients with early stages of POP or for those who prefer less invasive procedures.

Besides the laser therapies, stimulating fibroblast activity and ECM remodeling in POP patients could be achieved through the potential injectable therapies of exogenous IGF-1 delivery and LARP6-targeted modulators. Their use in recombinant formulation for wound healing, bone repair, and tissue regeneration makes them applicable in pelvic floor disorders. Likewise, vaginal fibroblasts’ collagen synthesis and ECM integrity could be improved by small molecule LARP6 activators or targeted gene therapy approaches. The effectiveness, safety, and delivery methods of these PAMs in LARP6 should be studies in non-surgical POP interventions and could be a step towards surgery-free treatment alternatives.

Conclusion

Both LARP6 and IGF-1 have important functions in the regulation of collagen metabolism, and their communication is relayed via the PI3K/AKT pathway which serves as a new theoretical basis for the development of POP. These results not only deepen the knowledge regarding the pathological mechanisms of POP, but also suggest possible molecular approaches towards the development of new preventive and therapeutic targets. More work should be done to convert those molecular ideas into real-world strategies that improve the health outcomes of the patients.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- POP:

-

Pelvic organ prolapse

- IGF-1:

-

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- LARP6:

-

La ribonucleoprotein structural domain family member 6

- COL:

-

Collagen

- WB:

-

Western blot

- RT-qPCR:

-

Real-Time quantitative PCR

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin-Eosin

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- mIHC:

-

Multiplex immunofluorescence

- SiRNA:

-

Small interfering RNA

- MMP:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase

- TIMP:

-

Inhibitors of metalloproteinase

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

References

Marcu, R. D. et al. Oxidative stress: A possible trigger for pelvic organ prolapse. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 3791934. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3791934 (2020).

Heit, M. et al. Predicting treatment choice for patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 101, 1279–1284. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00359-4 (2003).

Barber, M. D., Visco, A. G., Wyman, J. F., Fantl, J. A. & Bump, R. C. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 99, 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01727-6 (2002).

Guler, Z. & Roovers, J. Role of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts on the pathogenesis and treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Biomolecules 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12010094 (2022).

Ewies, A. A., Al-Azzawi, F. & Thompson, J. Changes in extracellular matrix proteins in the Cardinal ligaments of post-menopausal women with or without prolapse: a computerized Immunohistomorphometric analysis. Hum. Reprod. 18, 2189–2195. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deg420 (2003).

Kufaishi, H., Alarab, M., Drutz, H., Lye, S. & Shynlova, O. Comparative characterization of vaginal cells derived from premenopausal women with and without severe pelvic organ prolapse. Reprod. Sci. 23, 931–943. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719115625840 (2016).

Reddy, K. V. & Mangale, S. S. Integrin receptors: the dynamic modulators of endometrial function. Tissue Cell. 35, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0040-8166(03)00039-9 (2003).

Zhang, Y. & Stefanovic, B. LARP6 Meets collagen mRNA: specific regulation of type I collagen expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17030419 (2016).

Stefanovic, B., Manojlovic, Z., Vied, C., Badger, C. D. & Stefanovic, L. Discovery and evaluation of inhibitor of LARP6 as specific antifibrotic compound. Sci. Rep. 9, 326. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36841-y (2019).

Chen, L. et al. LARP6 regulates keloid fibroblast proliferation, invasion, and ability to synthesize collagen. J. Invest. Dermatol. 142, 2395–2405e2397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2022.01.028 (2022).

Zhang, Y. & Stefanovic, B. Akt mediated phosphorylation of LARP6; critical step in biosynthesis of type I collagen. Sci. Rep. 6, 22597. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22597 (2016).

Blackstock, C. D. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 increases synthesis of collagen type I via induction of the mRNA-binding protein LARP6 expression and binding to the 5’ stem-loop of COL1a1 and COL1a2 mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 7264–7274. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.518951 (2014).

Guo, Y. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes osteogenic differentiation and collagen I alpha 2 synthesis via induction of mRNA-binding protein LARP6 expression. Dev. Growth Differ. 59, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/dgd.12342 (2017).

Venken, K. et al. Impact of androgens, growth hormone, and IGF-I on bone and muscle in male mice during puberty. J. Bone Mineral. Research: Official J. Am. Soc. Bone Mineral. Res. 22, 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.060911 (2007).

Hansen, M. et al. Local administration of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) stimulates tendon collagen synthesis in humans. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 23, 614–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01431.x (2013).

Hung, C. F., Rohani, M. G., Lee, S. S., Chen, P. & Schnapp, L. M. Role of IGF-1 pathway in lung fibroblast activation. Respir. Res. 14, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-14-102 (2013).

Tian, F., Wang, Y. & Bikle, D. D. IGF-1 signaling mediated cell-specific skeletal mechano-transduction. J. Orthop. Research: Official Publication Orthop. Res. Soc. 36, 576–583. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.23767 (2018).

Huang, L. et al. Cellular senescence: A pathogenic mechanism of pelvic organ prolapse (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 22, 2155–2162. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2020.11339 (2020).

Diedrich, C. M., Roovers, J. P., Smit, T. H. & Guler, Z. Fully absorbable poly-4-hydroxybutyrate implants exhibit more favorable cell-matrix interactions than polypropylene. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 120, 111702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2020.111702 (2021).

Bailey, A. J. Molecular mechanisms of ageing in connective tissues. Mech. Ageing Dev. 122, 735–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00225-1 (2001).

Hu, Y., Wu, R., Li, H., Gu, Y. & Wei, W. Expression and significance of metalloproteinase and collagen in vaginal wall tissues of patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 47, 698–705 (2017).

Söderberg, M. W., Falconer, C., Byström, B., Malmström, A. & Ekman, G. Young women with genital prolapse have a low collagen concentration. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 83, 1193–1198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00438.x (2004).

Ra, H. J. & Parks, W. C. Control of matrix metalloproteinase catalytic activity. Matrix Biology: J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biology. 26, 587–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2007.07.001 (2007).

Budatha, M. et al. Extracellular matrix proteases contribute to progression of pelvic organ prolapse in mice and humans. J. Clin. Investig. 121, 2048–2059. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci45636 (2011).

Alperin, M. & Moalli, P. A. Remodeling of vaginal connective tissue in patients with prolapse. Curr. Opin. Obst. Gynecol. 18, 544–550. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gco.0000242958.25244.ff (2006).

Ruiz-Zapata, A. M. et al. Fibroblasts from women with pelvic organ prolapse show differential mechanoresponses depending on surface substrates. Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 1567–1575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2069-z (2013).

Vitale, S. G. et al. Efficacy and safety of Non-Ablative dual wavelength diode laser therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A Single-Center prospective study. Adv. Ther. 41(12), 4617–4627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-03004-7 (2024).

Woźniak, A. et al. Efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause in Short-Term Evaluation-Preliminary study. Biomedicines 11(5), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11051304 (2023).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81971365) and the Science and Technology Innovation Team of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 202204051002031), 2019 Shanxi Provincial Key Research and Development Program (International Science and Technology Cooperation) Project (No.: 201903D421060), 2020 Overseas Students Science and Technology Activities Project (Key Project) (No.: 20200007), 2024 Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project (Approval No.: 2024ZYY2C037) and Research on the Collagen Metabolism Mechanism of ADMSCs Exosome-Composite Hydrogel in the Treatment of SUI(Project No. YDZJSX2025D076).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K.: investigation, methods, analyses, writing the original manuscript, further writing, reviewing and editing.L.W., L.W.: conceptualisation, design and revisions.L.W., M.G.: participation in sample collection and clinical data collection.W.W., X.L.: supervision and obtaining funding. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The acquisition of human data for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Baiqun Hospital, Shanxi Province, China (no. SBQLL-2024-404). The aims and the methods of the study were verbally explained to the participants. Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants could withdraw from the study at will. They were assured of the confidentiality of their data. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, L., Wei, L., Wang, L. et al. IGF-1 regulates LARP6-mediated collagen metabolism in vaginal fibroblasts of POP patients via the PI3K/AKT pathway. Sci Rep 15, 21977 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08509-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08509-x