Abstract

PAPE (post-activation performance enhancement) has gained attention in sports science due to its potential to enhance athletic performance. This study aimed to investigate the effects of different PAPE activation methods, including non-activation (CON), Dynamic High Inertia Load (DYN), Specific Isometric Contraction (ISO), and Back Squat (BSQ), on standing start sprint performance in elite female track cyclists. A randomised, counterbalanced experimental design was used, with eight elite female track cyclists (age: 23.3 ± 1.3 years; height: 1.66 ± 0.02 m; weight: 62 ± 1 kg). Each participant participated in four activation experiments, each performing one of the four activation protocols (CON, DYN, ISO, BSQ). Each experiment included four tests: pre-activation (PRE), post-activation at 4 min (POST 4), post-activation at 8 min (POST 8), and post-activation at 12 min (POST 12). Each test consisted of a 62.5-metre standing start time trial (TT), with TT time, peak power output (PPO), and peak torque (PT) measured. The Friedman test was used for the main effect analysis. The DYN significantly improved sprint performance, with TT time decreased at POST 4 (p = 0.019) and PT increased (p = 0.003). The ISO improvements in PT at POST 12 (p = 0.044), but the TT time remained unchanged (p > 0.05). The BSQ showed no significant performance enhancement in TT time or PT (p > 0.05). DYN activation is the most effective PAPE method for improving standing start sprint performance in elite female track cyclists, with optimal effects observed 4 min post-activation. While ISO may improve peak torque, it did not enhance sprint time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sprint track cycling, a dynamic and intensely competitive sport, distinguishes itself from other forms of cycling through its unique demands and characteristics1. Unlike road cycling, which emphasizes endurance and strategy over long distances, or mountain biking (MTB), which demands technical skill and adaptability to varied terrains, sprint track cycling is characterized by its explosive power, precision, and the highly controlled environment of the velodrome2. The differences between these disciplines extend beyond the physical demands placed on athletes; they encompass equipment, training methodologies, and even the psychological approach to competition3. This makes sprint track cycling a distinct and fascinating area of study within the broader world of cycling sports.

Studies have shown that the anaerobic capacity and peak power output of sprint track cyclists are significantly higher than those of athletes in other cycling disciplines. For example, research has found that elite sprint track cyclists can achieve peak power outputs exceeding 2000 watts during the initial acceleration phase, whereas road cyclists typically reach peak power outputs between 1000 and 1500 watts1. Additionally, sprint track cyclists demonstrate remarkable muscular coordination efficiency during high-speed riding, particularly in the start and sprint phases, with highly specific activation patterns and force output in the lower limb muscles4. the design features of track cycling, such as fixed gear ratios and the absence of braking systems, demand exceptional technical precision and body control from athletes when riding at high speeds. Research indicates that fixed gear ratios not only enhance energy transfer efficiency but also require athletes to maintain a stable cadence and posture during high-speed riding to minimise energy loss5. Furthermore, when navigating banked turns, sprint track cyclists must precisely adjust their body lean angles and centre of gravity to maintain balance and speed, placing significant demands on core strength and coordination6. These unique physiological and biomechanical characteristics shape the training and competition strategies of sprint track cyclists. Post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) is a physiological phenomenon that refers to the enhancement of muscle force output or power performance in subsequent movements following pre-conditioning with high-intensity or maximal muscle contractions (such as weighted squats, sprinting, etc.)7. This phenomenon is commonly used to improve athletic performance in short-duration, high-intensity activities, such as sprinting, jumping, or cycling sprints8.

In recent years, several studies have focused on the effects of PAPE on track cycling performance. Munro et al. (2017) found improvements in laboratory tests of fatigue-free power-frequency curves following dynamic and isometric activation protocols9. Dynamic activation (DYN) and isometric activation (ISO) are two distinct methods of muscle activation, each inducing the PAPE effect through dynamic and isometric contractions, respectively. DYN involves dynamic movements under high inertial loads, such as rapid pedaling, to stimulate muscles and enhance explosive power within a short timeframe. In contrast, ISO enhances neuromuscular excitability and coordination through isometric contractions, such as maintaining maximal force, with its effects manifesting over a longer period. The differing mechanisms and recovery time windows of these activation methods underscore their unique scientific and practical significance in improving sprint and explosive performance9,10. Li and Liang (2024) further refined activation protocols and discovered enhanced effects of dynamic and isometric activation on the 250 m time trial performance and improvements in fatigue-free power-frequency curves during field tests11. Their findings provide further support for the power-frequency profile model for track cycling, initially established by Gardner et al. (2011)12 and later corroborated by Dunst et al. (2021, 2022, 2023)13,14,15,16.

The application of PAPE in track cycling and its impact on cycling performance has garnered some attention, but research in this area is still in its early stages. Current research on PAPE in track cycling has primarily focused on laboratory-based protocols or isolated performance metrics, with limited translation to real-world sprint performance, particularly leaving a significant gap in understanding its effects on standing start performance (62.5-metre time trial; TT).

To address these gaps, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of four distinct PAPE activation protocols—DYN, ISO, back squat activation (BSQ) and CON—on 62.5-metre standing start sprint performance in elite female track cyclists. We hypothesised that: 1.DYN would elicit the greatest improvement in sprint time and peak power output (PPO) due to its biomechanical specificity to the acceleration phase of track cycling; 2.ISO would enhance peak torque (PT) but show limited impact on sprint time, as it maximises force production without directly replicating sprint-specific movement patterns. 3.BSQ, despite its widespread use in strength training, would yield no significant performance benefits due to insufficient neuromuscular specificity to the demands of track cycling. 4.CON (control condition) would show no significant changes in sprint time, PPO, or PT, as it lacks any specific activation stimulus to induce PAPE. By integrating field-based 62.5 m TT with temporal analysis of post-activation intervals (4, 8, and 12 min), this study aims to provide actionable insights into optimising PAPE protocols for elite female athletes, bridging the gap between laboratory findings and competitive practice.

Materials and methods

Participants

Eight elite female track cyclists from the Henan Province track cycling team and the Chinese National Cycling Team were selected as participants (mean ± standard deviation: age: 23.3 ± 1.3 years; height: 1.66 ± 0.02 m; weight: 62 ± 1 kg; training years: 7.6 ± 0.7 years). All participants provided written informed consent, were informed of the study’s procedures, benefits, and risks, and voluntarily agreed to participate.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: track cyclists aged 18 to 25 years; at least a elite Level athlete (Competing at the international level)17 with a minimum of five years of track cycling experience, primarily competing in sprint cycling events (e.g., team sprint, 250 m time trial, 500 m time trial, keirin, and sprint); physically healthy with no history of cardiovascular, metabolic, or musculoskeletal diseases ability to independently perform standing start techniques; willingness and ability to participate in all activation-testing sessions during the study period.

The exclusion criteria included severe lower limb injuries were defined as ligament tears (e.g., ACL rupture), fractures (e.g., tibial or fibular fractures), or muscle strains (e.g., grade II or higher hamstring strain); use of medications that could affect athletic performance (e.g., steroids, antidepressants) within the past three months; consumption of stimulant substances during the study period, including caffeine or other substances that may affect cognitive function and reaction time (e.g., energy drinks, stimulants); Participants who were menstruating (i.e., experiencing menstrual bleeding) at the time of testing were excluded, to minimize potential confounding effects of menstrual-related discomfort or hormonal fluctuations on short-duration high-intensity performance.

Participants wore competition-grade cycling apparel (Champion System), shoes (Sidi), and helmets (Lazer Victor) of the same brand and model during all experimental sessions to ensure standardisation of external equipment-related variables. A road bicycle (LOOK) was used for the warm-up, while a track bicycle (LOOK) was used for the formal experiment. The track bicycle had a tri-spoke front wheel and a disc rear wheel. The gear ratio was set to 3.4.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Sports Science Experiment Ethics Committee of Beijing Sport University (2023270 H).

Design

This study employed a randomised controlled trial to investigate the effects of different activation methods on the sprint start performance of cyclists. All tests were conducted in the Guangzhou Indoor Velodrome, a regulated indoor environment designed for elite competition. All experimental sessions were conducted at the same time of day (09:00 AM) to control for the potential effects of circadian rhythms on performance. Prior to the study, participants were randomly assigned to an activation-testing session sequence (CON, DYN, ISO, BSQ). According to the sequence, each participants completed four separate activation-testing sessions, with each session consisting of one activation protocol and four performance tests. The session was structured as follows: it began with a baseline performance test (pre-activation, PRE), followed by the activation protocol. After the activation, participants underwent three additional performance tests at intervals of 4 min (POST 4), 8 min (POST 8), and 12 min (POST 12). Between each of these tests, participants were given a 4-minute rest periodThere was a 48-hour interval between each activation-testing session.

Before beginning the experiment, the technical team installed and calibrated the SRM power meter (SRM ORIGIN-TRACK CARBON). Participants then completed a warm-up routine, which included joint mobility exercises, dynamic stretching, and 15 min of low-intensity cycling (below 15 km/h). Before conducting the activation-testing session, the researchers provided training on the activation-testing session to all participants. The experimental design and procedure are shown in the Fig. 1.

Standing start performance

Following the competition rules for a standing start in a team sprint, which included the use of a standard starting block and a countdown timing system, the 62.5 m TT was tested. The FinishLynx timing system was used to measure the time. During this process, the SRM power meter was synchronised with the timing equipment to collect data, which was then transferred to computers and mobile devices to gather 62.5 m TT times, peak power output (PPO), and peak torque (PT).

Activation methods

The CON did not undergo activation interventions, opting instead for active recovery. This involved a 12-minute cycling session at a leisurely pace, with the speed maintained below 10 km/h, ensuring the duration was generally consistent with the time frames used for the other activation protocols.

The DYN simulated the acceleration load using a modified indoor cycling trainer. This trainer is equipped with a special 40 kg flywheel, 8 cm in width and 70 cm in diameter, with a 6:1 gear ratio. The flywheel’s rim is fitted with rubber rollers and tension springs. During the activation, participants performed out-of-saddle pedalling from a standing start position using their dominant leg. They completed 4 full pedal strokes per leg, repeated for 4 sets with a 2-minute rest interval between sets9,11.

In the ISO, the pedal and flywheel were secured using a hydraulic jack and a steel rod to minimise rotation. Participants selected their dominant leg and performed out-of-saddle pedalling with maximum force for 4 s, maintaining peak effort. This was repeated for four sets with a 2-minute rest between sets. Four different crank positions were tested: 45°, 60°, 90°, and 135°, each held for 4 s9,11.

The BSQ performed squats with an 80% 1-repetition maximum (1RM) load. The squats were controlled, with participants completing four repetitions per set, repeated for four sets, with a 2-minute rest interval between sets. Prior to this study, a 1RM squat test was conducted following the NSCA 1RM protocol during physical training sessions to determine the load corresponding to 80% of each athlete’s 1RM. The training volume was adjusted to ensure equivalency in stress levels across the different activation strategies.

Statistical analysis

The data were compiled and subjected to statistical analysis using Excel 2021 and SPSS 27.0 (IBM, USA). The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The homogeneity of variance was evaluated using Levene’s test. All data are presented as median (interquartile range, IQR). A repeated-measures Friedman test was used to assess the inter-group and time effects of different activation methods. Significant main effects were further analysed using Nemenyi post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Effect sizes for pairwise comparisons were reported using Cohen’s d. A Cohen’s d greater than 0.8 was considered large, between 0.8 and 0.5 as medium, between 0.5 and 0.2 as small, and less than 0.2 as insignificant40. For comparisons involving more than two groups, Cohen’s f was used as the effect size measure, with Cohen’s f greater than 0.40 considered large, between 0.40 and 0.25 as medium, between 0.25 and 0.10 as small, and less than 0.10 as insignificant40. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Before the activation intervention, no significant group effect was observed in the 62.5 m TT (p = 0.187, f = 0.204, small effect size). Four minutes after activation, a significant main effect between groups was observed in the 62.5 m TT (p = 0.001, f = 0.654, large effect size). Eight minutes after activation, a significant main effect between groups was observed in the 62.5 m TT (p = 0.012, f = 0.128, medium effect size). Twelve minutes after activation, a significant main effect between groups was observed in the 62.5 m TT (p = 0.009, f = 0.165, large effect size).

Before activation, no significant group effect was observed in the PPO (p = 0.893, f = 0.028, insignificant effect size). However, four minutes after activation, a significant group effect was observed (p = 0.003, f = 0.146, small effect size). Eight minutes after activation, no significant group effect was found (p = 0.347, f = 0.098, insignificant effect size), while twelve minutes after activation, a significant group effect was observed (p = 0.034, f = 0.185, small effect size).

Before activation, no significant difference was observed in the PT (p = 0.620, f = 0.789, large effect size). Four minutes after activation, a significant group effect was observed (p = 0.002, f = 4.279, large effect size). Eight minutes after activation, a significant group effect in PT was observed (p = 0.002, f = 2.904, large effect size). Twelve minutes after activation, a significant group effect was also observed (p = 0.005, f = 2.371, large effect size). The above results are shown in Table 1.

The CON group did not show a significant time effect in the 62.5 m TT (p = 0.226, f = 0.235, small effect size). The DYN group showed a significant time effect (p = 0.001, f = 0.547, large effect size). The ISO group also showed a significant time effect (p = 0.006, f = 0.419, large effect size). No significant time effect was observed in the BSQ group (p = 0.290, f = 0.186, small effect size).

No significant time effect was observed in the CON group for PPO (p = 0.513, f = 0.108, small effect size). The DYN group showed a significant time effect (p = 0.016, f = 0.348, medium effect size). The ISO group also showed a significant time effect for PPO (p = 0.002, f = 0.146, small effect size). No significant time effect was observed in the BSQ group (p = 0.528, f = 0.110, small effect size).

No significant time effect was observed for PT in the CON group (p = 0.086, f = 1.485, large effect size). A significant time effect was observed for PT in the DYN group (p = 0.002, f = 3.454, large effect size). A significant time effect was also observed for PT in the ISO group (p = 0.017, f = 2.007, large effect size). No significant time effect was observed for PT in the BSQ group (p = 0.271, f = 0.825, large effect size). The above results are shown in Table 2.

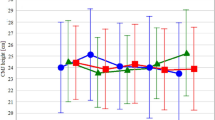

Four minutes after activation, a significant difference was observed between the DYN and CON groups in the 62.5 m TT (p = 0.001, d = 1.494, large effect size). No significant differences were found between the other groups and CON at the same time point (p > 0.05). Eight minutes after activation, the 62.5 m TT in the BSQ group was significantly lower than CON (p = 0.005, d = 1.385, large effect size). Twelve minutes after activation, a significant difference was observed between the ISO and CON groups (p = 0.014, d = 1.344, large effect size), while no significant differences were found between the other groups and CON (p > 0.05). Four minutes after activation, the DYN group showed a significant decrease in the 62.5 m TT compared to before activation (p = 0.019, d = 1.351, large effect size). No significant differences were observed at other time points compared to pre-activation. For the ISO group, no significant differences were observed at any time point post-activation compared to pre-activation (p > 0.05). Similarly, for the BSQ group, no significant differences were found at the three post-activation time points compared to pre-activation (p > 0.05).

Four minutes after activation, the DYN group showed significantly higher PPO than the CON group (p = 0.010, d = 1.351, large effect size). No significant differences were observed between CON and the other groups at the same time point (p > 0.05). At twelve minutes post-activation, no significant differences were found in multiple comparisons (p > 0.05). The DYN group showed no significant differences at any post-activation time point compared to pre-activation (p > 0.05). Twelve minutes after activation, the ISO group showed significantly higher PPO compared to pre-activation (p = 0.034, d = 0.718, medium effect size), while no significant differences were observed at other time points compared to pre-activation (p > 0.05).

Four minutes after activation, the DYN group showed significantly higher PT than the CON group (p = 0.003, d = 2.606, large effect size). No significant differences were observed between the other groups and CON at the same time point (p > 0.05). Eight minutes after activation, the DYN group showed significantly higher PT than CON (p = 0.001, d = 1.998, large effect size). Twelve minutes after activation, the ISO group showed a significant difference in PT compared to CON (p = 0.005, d = 1.631, large effect size), while no significant differences were found between the other groups and CON at the same time point (p > 0.05).

Four minutes after activation, the DYN group showed significantly higher PT compared to pre-activation (p = 0.003, d = 3.277, large effect size). No significant differences were observed at other time points compared to pre-activation (p > 0.05). Twelve minutes after activation, the ISO group showed significantly higher PT compared to pre-activation (p = 0.044, d = 1.577, large effect size). No significant differences were observed at other time points compared to pre-activation (p > 0.05). No significant differences were found in multiple comparisons before and after activation for the BSQ group (p > 0.05). The above results are shown in Fig. 2.

Multiple comparisons of performance differences before and after activation with different activation methods at various time points. (a) Multiple comparisons of 62.5 m TT results across different activation methods and time points; (b) Multiple comparisons of PPO results across different activation methods and time points; (c) Multiple comparisons of PT results across different activation methods and time points; CON: the non-activation control condition; DYN: dynamic activation; ISO: isometric activation; BSQ: back squat activation; PRE: pre-activation; POST 4: post-activation at 4 min; POST 8: post-activation at 8 min; POST 12: post-activation at 12 min; TT: 62.5-metre time trial; PPO: peak power output; PT: peak torque; * denotes significant differences between groups and CON (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01); # indicates significant differences between time points and pre-activation (# p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of four activation methods and different post-activation times on the standing start sprint performance of elite track cyclists. The results showed that after DYN activation, the 62.5 m TT time significantly decreased, and PT significantly increased at 4 min post-activation. In contrast, ISO activation resulted in a potentiation effect at 12 min, with a significant increase in PT. However, the reduction in 62.5 m TT time was not statistically significant. Mixed results for BSQ indicated that its induced potentiation effect on standing start performance was not statistically significant.

The findings of this study further confirm previous research on the potentiation of track cycling performance through PAPE. Consistent with the studies of Munro et al. (2017)9 and Li and Liang (2024)11the results of this study indicate that DYN activation enhanced relevant performance, including cycling time and PT, at 4 min post-activation. Munro et al. (2017) also observed an increase in PPO after activation9although this was not reported in the present study. The discrepancy can be attributed to differences between laboratory-based tests and field-based tests, as well as the different statistical methods used. In Li et al. (2024), an increase in peak power was also observed, alongside improvements in high-cadence sprints with ISO activation11. However, aside from the improvement in PT at 12 min post-activation, no additional benefits from ISO were found in this study. The difference may be due to the fact that this study followed a classical PAPE experimental repeated-measures design, which helped control for additional variables such as the participants’ functional status and biological rhythms. However, this design may have led to cumulative fatigue during the tests. In contrast, Li et al. (2024) used a separate activation test to avoid test fatigue, measured a full single-lap sprint rather than focusing on the standing start, and employed a different gear ratio11which may explain some of the observed differences.

The aforementioned studies also inferred, through power-frequency profiles, that DYN is more effective in improving low-cadence sprints, a conclusion that is supported by the present study9,11. During the standing start, the athlete’s cadence begins from zero and needs to rapidly increase through high torque and a gradual rise in cadence to overcome the significant resistance18. This process corresponds to the ascending limb of the power-frequency curve. The improvement in 62.5 m TT time and the increase in PT following DYN activation indicate that it can significantly enhance performance during low-cadence sprints.The enhancement of standing start performance following DYN activation can be attributed to the physiological and biochemical characteristics of dynamic activation. DYN activation enhances neuromuscular excitability by increasing motor unit recruitment and firing rates, as well as facilitating corticospinal tract excitability, leading to improved force production following a conditioning activity19,20. Additionally, phosphorylation of myosin light chains enhances actin–myosin interaction and cross-bridge cycling efficiency. While PAPE has been associated with increased myofilament Ca²⁺ sensitivity—primarily via enhanced troponin C affinity—this effect should be interpreted with caution. Type II muscle fibers, which are predominantly recruited during explosive activities and PAPE-inducing contractions, inherently require higher intracellular Ca²⁺ concentrations to initiate force production due to their lower calcium sensitivity compared to Type I fibers. Therefore, although increased calcium sensitivity may optimize force generation at submaximal calcium levels, its impact in PAPE likely reflects enhanced efficiency under already elevated calcium availability, rather than a shift in fiber recruitment thresholds7,21.Furthermore, dynamic activities increase muscle temperature, which augments enzymatic activity and accelerates ATP resynthesis—critical for short-duration, high-intensity sprints22,23,24.

ISO activation increases muscle tension and stiffness by maintaining muscle contraction at a specific length, which can generate greater force output in subsequent activities25,26. This type of activation optimises neural response, enhancing strength and speed through improved synchronisation of motor unit activation27,28. Biochemically, ISO activation likely alters the local metabolic environment within the muscle, such as pH and ion concentration adjustments, aiding in improved muscle contraction efficiency during subsequent exercise29,30,31. Additionally, it is shown to potentially increase the excitability of α-motoneurons as evidenced by changes in the H-reflex, suggesting that the nervous system’s responsiveness to stimuli is heightened, which could theoretically enhance performance in subsequent motor tasks, particularly those requiring quick and powerful muscular responses and enhancing the efficiency of cyclic contractions21,32. In contrast to DYN activation, the effects of ISO activation occur later and are more suited to fast, repetitive cycling movements and endurance-based activities9,11,33. The lower cadence of the 62.5 m TT sprint, along with the observed increase in PT, highlights the potential advantages of ISO activation, as well as the specificity of the activation angle34.

The failure of BSQ to effectively induce an enhancement effect can be attributed to the differences between the back squat movement and the standing start movement pattern, as well as the unnecessary fatigue caused by the multi-joint concentric movements involved in squatting35,36,37.

The benefits of DYN activation were significantly greater than those of ISO and BSQ; however, this does not imply that the other methods are unsuitable. Based on the findings of this study, DYN can be used to improve standing start performance and may be applied in the warm-up routines of elite athletes responsible for the start in team sprints and time trials. Specifically, within the context of this study, DYN could also be beneficial in enhancing performance in standing start training sessions for elite athletes, contributing to improved training intensity and quality. In practical applications, individual differences among athletes should be taken into account to develop personalised activation protocols.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, which is constrained by the limited number of participants in the sport, the inherent difficulty of the events, and the elite athlete requirements. Additionally, the study focused exclusively on female elite athletes, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The research did not further investigate the fatigue characteristics post-activation or the performance of each pedal stroke during specific moments of the sprint, which could have provided more profound insights into the results. Future studies could explore more in-depth kinematic and dynamic changes post-activation, as well as the physiological and biochemical characteristics of the body at different time points post-activation. Furthermore, this study focused solely on the standing start phase of the sprint, and further research is needed to explore high-speed sprints and the maintenance of speed. One limitation of this study is the lack of detailed hormonal phase tracking. However, to reduce the potential impact of menstruation-related symptoms, testing was not conducted during the menstrual bleeding phase. Previous reviews indicate that while average performance differences across menstrual phases are small, some athletes may experience reduced anaerobic performance during menses due to pain or fatigue38,39. Thus, excluding testing during menses offers a practical compromise for acute performance studies.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that DYN elicited a significant improvement in the standing start performance of elite female track cyclists, with a reduction in 62.5 m TT time and an increase in PT observed at 4 min post-activation. In contrast, ISO led to an enhancement in PT at 12 min post-activation but did not significantly affect 62.5 m TT performance. These findings suggest that DYN induces a more immediate and pronounced PAPE effect compared to ISO and BSQ, likely due to the greater neuromuscular potentiation and specificity of movement patterns associated with high-velocity, high-inertia dynamic contractions. The delayed effect of ISO may reflect its reliance on sustained neural excitation and muscle coordination adaptations over a longer recovery window. These insights provide valuable practical implications for optimizing pre-race activation strategies in sprint cycling.

Data availability

Data and images that support the findings of this study are available on request from the lead contact. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yapu Liang (yapu_liang@bsu.edu.cn).

References

Craig, N. P. & Norton, K. I. Characteristics of track cycling. Sports Med. 31, 457–468. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200131070-00001 (2001).

Burke, E. High-tech Cycling (Human Kinetics, 2003).

Jeukendrup, A. & Gleeson, M. Sport nutrition: an introduction to energy production and performance. (2010).

Hautier, C., Linossier, M., Belli, A., Lacour, J. & Arsac, L. Optimal velocity for maximal power production in non-isokinetic cycling is related to muscle fibre type composition. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 74, 114–118 (1996).

Bertucci, W., Taiar, R. & Grappe, F. Differences between sprint tests under laboratory and actual cycling conditions. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness. 45, 277 (2005).

Martin, J. C., Davidson, C. J. & Pardyjak, E. R. Understanding sprint-cycling performance: the integration of muscle power, resistance, and modeling. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2, 5–21 (2007).

Blazevich, A. J. & Babault, N. Post-activation potentiation versus post-activation performance enhancement in humans: historical perspective, underlying mechanisms, and current issues. Front. Physiol. 10, 479198 (2019).

Cuenca-Fernández, F. et al. Nonlocalized postactivation performance enhancement (PAPE) effects in trained athletes: a pilot study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 42, 1122–1125 (2017).

Munro, L. A., Stannard, S. R., Fink, P. W. & Foskett, A. Potentiation of sprint cycling performance: the effects of a high-inertia ergometer warm-up. J. Sports Sci. 35, 1442–1450. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1215492 (2017).

Dobbs, W. C., Tolusso, D. V., Fedewa, M. V. & Esco, M. R. Effect of postactivation potentiation on explosive vertical jump: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 33, 2009–2018 (2019).

Li, T. & Liang, Y. The effects of different post-activation potentiation strategies on the performance of elite female track cyclists in position 1 of team sprint. Sci. Rep. 14, 24604. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75464-4 (2024).

Gardner, A. S., Martin, J. C., Martin, D. T., Barras, M. & Jenkins, D. G. Maximal torque-and power-pedaling rate relationships for elite sprint cyclists in laboratory and field tests. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 101, 287–292 (2007).

Dunst, A. K. & Grüneberger, R. A. Novel approach of modelling and predicting track cycling sprint performance. Appl. Sci. 11, 12098 (2021).

Dunst, A. K., Grüneberger, R. & Holmberg, H. C. Modeling optimal Cadence as a function of time during maximal sprint exercises can improve performance by elite track cyclists. Appl. Sci. 11, 12105 (2021).

Dunst, A. K., Hesse, C., Ueberschär, O. & Holmberg, H. C. Fatigue-Free Force-Velocity and Power-Velocity profiles for elite track sprint cyclists: the influence of duration, gear ratio and pedalling rates. Sports 10, 130 (2022).

Dunst, A. K., Hesse, C. & Ueberschär, O. The concept of optimal dynamic pedalling rate and its application to power output and fatigue in track cycling Sprinters—A case study. Sports 11, 19 (2023).

McKay, A. K. A. et al. Defining training and performance caliber: A participant classification framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 17, 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2021-0451 (2022).

Nardello, F., Bernabè, R., Bettega, S., Zandomeneghi, M. & Zamparo, P. Kinematics of backward standing starts in elite cyclists: the effect of initial crank angle. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 94, 476–484 (2023).

Xenofondos, A., Papavasileiou, A., Bassa, E., Vrabas, I. S. & Patikas, D. A. Postactivation potentiation and the asynchronous action of muscular and neural responses. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 18, 852–860 (2023).

Demirci, C. & Aydogan Arslan, S. in Functional Exercise Anatomy and Physiology for Physiotherapists 391–406, Springer, (2023).

Hodgson, M., Docherty, D. & Robbins, D. Post-activation potentiation: underlying physiology and implications for motor performance. Sports Med. 35, 585–595 (2005).

Garbisu-Hualde, A. & Santos-Concejero, J. Post-activation potentiation in strength training: A systematic review of the scientific literature. J. Hum. Kinetics. 78, 141–150 (2021).

Pajerska, K., Zajac, T., Mostowik, A., Mrzyglod, S. & Golas, A. Post Activation Potentiation (PAP) and its Application in the Development of Speed and Explosive Strength in Female Soccer Players A review ( 2021).

Mendez-Villanueva, A., Edge, J., Suriano, R., Hamer, P. & Bishop, D. The recovery of repeated-sprint exercise is associated with PCr resynthesis, while muscle pH and EMG amplitude remain depressed. PLoS One. 7, e51977. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051977 (2012).

Lim, J. J. & Kong, P. W. Effects of isometric and dynamic postactivation potentiation protocols on maximal sprint performance. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 27, 2730–2736 (2013).

Prieske, O., Behrens, M., Chaabene, H., Granacher, U. & Maffiuletti, N. A. Time to differentiate postactivation potentiation from performance enhancement in the strength and conditioning community. Sports Med. 50, 1559–1565 (2020).

JUDGE, L., Moreau, C. & BURKE, J. Neural adaptations with sport-specific resistance training in highly skilled athletes. J. Sports Sci. 21, 419–427 (2003).

Kordi, M. et al. Cycling-specific isometric resistance training improves peak power output in elite sprint cyclists. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 30, 1594–1604. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13742 (2020).

Skurvydas, A. et al. What are the best isometric exercises of muscle potentiation? Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 119, 1029–1039 (2019).

Vargas-Molina, S. et al. Comparison of post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) after isometric and isotonic exercise on vertical jump performance. Plos One. 16, e0260866 (2021).

Eon, P., Jubeau, M. & Cattagni, T. Post-activation potentiation after isometric contractions is strongly related to contraction intensity despite the similar torque–time integral. Experiment. Physiol. (2024).

Garcia, T. et al. Single-versus multi-joint isometric protocols to induce a post activation potentiation effect on squat jump performance. Hum. Mov. 21, 71–80 (2020).

Harat, I. et al. Dynamic post-activation potentiation protocol improves rowing performance in experienced female rowers. J. Sports Sci. 38, 1615–1623 (2020).

Worn, R. L., Talpey, S. W. & Edwards, T. Pedal Quadrant-Specific strength and conditioning considerations for endurance cyclists. Strength. Conditioning J. 10, 1519 (2022).

Villalon-Gasch, L., Jimenez-Olmedo, J. M., Sebastia-Amat, S. & Pueo, B. Squat-based post-activation potentiation improves the vertical jump of elite female volleyball players. (2020).

Atalağ, O., Kurt, C., Solyomvari, E., Sands, J. & Cline, C. Postactivation potentiation effects of back squat and barbell hip thrust exercise on vertical jump and sprinting performance. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 60, 1223–1230 (2020).

McKean, M. R., Dunn, P. K. & Burkett, B. J. Quantifying the movement and the influence of load in the back squat exercise. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 24, 1671–1679 (2010).

McNulty, K. L. et al. The effects of menstrual cycle phase on exercise performance in eumenorrheic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 50, 1813–1827 (2020).

de Jonge, X. A. J. Effects of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance. Sports Med. 33, 833–851 (2003).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Routledge, 2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely express their gratitude to Beijing Sport University, the Athletics and Cycling Training Centre of Henan Province, the Chinese National Cycling Team, and the Henan Provincial Track Cycling Team for their invaluable support and assistance throughout this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund, grant numbers 2021QN015 and 2023GCZX006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, Y.L. and T.L.; methodology, Y.L., J.L. and T.L.; software, T.L.; validation, Y.L. and T.L.; formal analysis, Y.L. and T.L.; investigation, Y.G., S.B., Y.G., Q.L. and T.L.; resources, J.L. and Y.L.; data curation, Q.Z., X.H., Y.L. and T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L., J.L. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L., Y.L. and T.L.; visualisation, T.L. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L. and L.L.; project administration, Y.L. and L.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Y., Li, T., Liu, J. et al. Effects of different activation strategies on standing start performance in elite female track cyclists. Sci Rep 15, 20827 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08577-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08577-z