Abstract

This study investigates the use of Waste Glass Powder (WGP) as a proportional replacement for cement in sustainable concrete production. In addition, changes in the bending capacity of the Reinforced Concrete (RC) Beams were examined by adding WGP at different rates (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%) to RC Beams with different steel reinforcement ratios (ρs = 0.0077 i.e. Φ8, ρs = 0.0121 i.e. Φ10, ρs = 0.0174 i.e. Φ12). To pursue this goal, 12 test specimens were evaluated and then confirmed to explore the bending productivity. The amount of longitudinal bar section area and WGP proportion were chosen as the key parameters. For this aim, experimental and analytical investigations were carried out by replacing cement with WGP in weight ratios of 10%, 20%, and 30% and considering three different longitudinal reinforcements (ρs = 0.0077 i.e. Φ8, Φ10, Φ12). The test results showed that tension reinforcement section area and WGP proportion dimensions had dissimilar rupture and flexure effects on RC Beams. Furthermore, investigational tests are confirmed with the help of the Digital Imagining Method, and the image processing method was used to identify the cracks/microcracks in RC Beams. Consequently, it is observed that each WGP ratio in the concrete combination has dissimilar bending and rupture properties on the RC Beams for experimental tests—10% of partial replacement of cement. It was found that a WGP ratio of more than 10% can significantly reduce the bending capacity of RC Beams. When the experimental test beams were compared with the analytical results, it was observed that the experimental results and analytical calculations are in agreement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The idea of using waste as a result of recycling materials to convert them into new products started in the last century. Different methods are also utilized to obtain more environmentally construction materials. One of the most widely used construction materials for a variety of purposes is concrete. Therefore, researchers have been working to increase concrete performance and sustainability. Many investigations have been conducted around the world highlighting the reusability of waste glass in construction materials1,2. In the beginning, the use of waste glass as a partial replacement for coarse aggregates (CA) and fine aggregates (FA) in concrete combinations was investigated by several researchers. Several investigations were concerned with waste glass powder (WGP) with concrete combinations in the literature3,4. In previous research conducted by Singh5, the effect of waste glass obtained from window applications on concrete properties was investigated by considering different CA variations. At the end of this investigation, Singh5 found that while a decrease was detected in slump value and fresh density properties, an improvement was detected in the related strength properties. Adaway and Wang6 investigated the effect of replacing waste container glass with fine aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete. For this aim, Adaway and Wang6 employed different amounts of waste materials such as 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, and 40%. At the end of this investigation, Adaway and Wang6 determined that replacing 30% finely crushed glass with FA increased the CS value compared to the reference concrete. Hama et al.7 investigated the influence of the amount of WGP, the amount of longitudinal steel reinforcement, and the spacing of transverse reinforcement on concrete properties. WGP was utilized as a substitute for cement in different proportions. For this aim, they prepared nine RC Beams. At the end of this investigation, Hama et al.7 found that RC Beams having WGP showed high resistance, and suitable bending behavior compared with reference RC Beams. Ramakrishnan et al.8 also effected another investigation to offer an experimental study on the effect of the mixture of crushed WGP and ground granulated blast furnace slag as a fractional substitution of cement, on the structural performance and permanence belongings of concrete. For this aim, Ramakrishnan et al.8 replaced cement with WGP from 5 to 45% in 5% increments and ground granulated blast furnace slag from 45 to 5% in 5% reductions, respectively. Furthermore, Ramakrishnan et al.8 prepared RC Beams to investigate the bending behavior. At the end of the bending tests, it was found that the performance of the beam including combined mix (cement + WGP + ground granulated blast furnace slag (50% cement + 15% WGP + 35% ground granulated blast furnace slag) in flexure was higher than the beam including (50% cement + 20% GP + 30% ground granulated blast furnace slag) since the ductile behavior in the (50% cement + 15% WGP + 35% ground granulated blast furnace slag) specimen was more pronounced than that in the (50% cement + 20% WGP + 30% ground granulated blast furnace slag) specimen.Haido et al.9 experimentally and numerically investigated the reusing of WGP as an additional for silica fume in high-strength concrete. In pursuance of this goal, 13 specimens consisting of 0.3 m width, 0.15 m depth, and 0.9 m span length were used in their investigations. At the end of their investigations, it was found that the reused WGP was considered as an alternative to the pozzolanic powder of silica fume. Yassen et al.10 examined the influence of including WGP on the shear resistance of RC Beams under bending load. For this aim, the investigational test program contains nine RC Beams of 150 × 150 × 900 mm considered to fail in shear. At the end of this study, Yassen et al.10 observed that using WGP enhanced the strength ability of the RC Beams and that may be realized through the rise in ultimate load for RC Beams including WGP compared to the control RC Beams. Elsayed et al.11 observed the bending and shear behavior of RC Beams having recycled CA, waste aluminum fiber, and WGP. For this aim, five concrete combinations including changed proportions of recycled CA, and waste aluminum fiber with the constant proportion of 20% of WGP as cement replacement were organized. Furthermore, 10 RC Beams were prepared and it was designed assuming that five of these beams collapsed in bending and the rest was designed to collapse in shear. it was found that the load-bearing capacity of experienced recycled CA concrete beams was enhanced by the addition of waste aluminum fiber. Furthermore, the ideal proportion of waste aluminum fiber that may be added to recycle CA concrete to contribute optimistic reactions to the whole performance of tested beams was found as 1%. In addition to the above-mentioned investigations, recently, experiments have been carried out on RC Beams using the image analysis method. Bayar and Bilir12 observed the rupture form and propagation in a random concrete via a machine learning algorithm. An unplanned picture of a concrete rupture positioned on the apparent was engaged from a common source and the rupture sizes and ways have been gauged. Kim et al.13 investigated image binarization for rupture identification, concentrating on optimum constraint resolution and proportional performance estimation for five common binarization approaches. Kim et al.13 prepared rupture images to achieve optimum limits by reducing mistakes in expected rupture widths. Rimkus et al.14 obtained pictures using the Digital Image Correlation (DIC) method for the rupture localization. For this aim, the image was changed to attain a firmly horizontal situation for the determination to eliminate the impact of perspective and shape deformation. Later, the vertical form of ruptures was used to confine their location. Rimkus and Gribniak15 also conducted another investigation to examine the impact of the dispersion of reinforcement bars on cracking behavior and failure of tensile elements. In this investigation, the failure examination was based on regular reinforcement and concrete external strains. The progress of fractures was examined using DIC. Fayyad and Lees16 also examined the rupture expansion in the RC beam via DIC which is an optical method for fracture observations. Fayyad and Lees16 experimentally observed the relationship between the rupture possessions and the possessions of the steel reinforcement and concrete. At the end of this investigation, it was observed that the images and quantification of the rupture properties of the RC beam could be identified via the results of the DIC method. The DIC optical technique was established to be a powerful option for evaluating the rupture opening displacements. The authors17 studied the shear performance of the RC beams with partial aggregate substation using crushed waste glass. DIC, experimental and theoretical analyses were conducted.

This study presents a unique comprehensive approach to the assessment of WGP as a replacement to cement in RC Beams. Unlike other research papers that mainly investigated WGP as mechanical strength impact alone, this paper covers the discussion regarding the influence of WGP replacement proportions and different diameters of longitudinal reinforcement that have a synergistic effect on the flexural behavior of the RC Beams. The shear performance of the RC beams with WGP replacement with cement was previously studied by the authors18. Besides, DIC to detect crack opening in real-time is an innovative application of experimental techniques for the enhancement of knowledge in structural behavior for different loading conditions. Accordingly, this experimental-analytical twofold approach covers existing literature gaps and extends new signals related to practical-structural consequences of WGP-reinforced sustainable concretes.

Materials and method

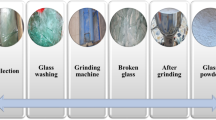

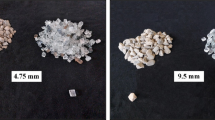

In this study, CEM-I 32.5 Portland cement was consumed with certain proportions of cement. The designed water-cement ratio was 0.5. Furthermore, the cement was replaced by WGP with weight proportions of 10%, 20%, and 30%. The WGP employed in this investigation is presented in Fig. 1. The proportion of FA to CA was fixed at one-to-one. A similar amount of 100–200 micron glass is fine glass rubbish. Fine aggregates range in size from 1 to 4 mm. A coarse aggregate size range of 5–12 mm was used. Cement particles ranged in size from 0.1 to 0.2 mm. The proportion of cement to aggregates was determined to be 20%. The details about the mixture and properties were given in19.

Three different types of experiments were conducted to evaluate the performance of concrete containing WGP. The mechanical results of the samples are given in Fig. 2. When the WGP ratio is equal to 30%, the compression capacity significantly decreased (43.5%). Besides, bending and splitting tensile strength decreased 16.3% and 25.6%, respectively. Following the values found in the literature, these findings are comparable20,21. Features of the sample are given in Table 1. Despite this concrete quality reduction, the present research finds WGP acceptable, easy to get in large quantities, a local eco-material, inexpensive, and appropriate for concrete construction economically and ecologically.

Mechanical results of concrete with WGP19.

There were a total of 12 different beams. To measure each effect, a test was carried out on the beam. The measurements of the RC Beams were determined to be 100 mm × 150 mm × 1000 mm. To achieve a bending behavior, stirrups of 6 mm diameter with spacing 10 cm and a shear span to an effective depth of 2.69 were chosen as appropriate parameters. The only rebars for tension are altered to Ф12, Ф 10, and Ф8, correspondingly. The steel reinforcement bars used are ribbed construction reinforcement. Both the reinforcement arrangement and the test configuration are represented in Fig. 3. It indicates the reinforcement layout, and Fig. 4 indicates the test setup. To evaluate the beam specimens, a 4-point loading configuration was used. The experimental setup included two different support types: hinged and fixed. The beam span is designated as 1000 mm. The loading is carried out beginning at the position in the middle.

The research focused primarily on the weight ratio of WGP as its primary variable, with the tension reinforcement ratio serving as its secondary parameter of interest. Three of these test beams were used as references and did not include any WGP, while the other test beams had varying amounts of WGP based on their wf ratios: 10%, 20%, and 30% respectively. Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of the test beams that have been collected.

To estimate the current bending capacities (Eq. 7) of the designed beams in the investigation, the equilibrium (Eqs. 3–6) and (Eqs. 1–2) equations were used (Fig. 5).

where c is the neutral axis depth (mm); εc is the strain of concrete; εs is the strain of tensile reinforcement; εs′ is the strain of compressive reinforcement; d is the effective depth (mm); d' is the distance from the center of the compression reinforcement to the outermost concrete fiber (mm); Fs and Fs′ are the forces in respectively the tensile and compressive reinforcement, Fc is the compressive force in concrete (N); r is the moment arm (mm); σc is the compressive stress in concrete (Eqs. 1 and 2) (MPa); Pmax is the maximum bearing load of the beam (N) (Eq. 8); a is the shear span (mm).

Eurocode 222 proposes the idealized stress–strain curves for concrete and steel. For stress–strain relationships of concrete and steel, expressions are given in Fig. 6. For the strain curve of concrete in the investigation, Eqs. (9) and (10) were used. In addition, for the stress–strain relationship, the cylinder CS of concrete (fck) and the yield strength of steel (fyk) were used without dividing by any safety factor. The cylindrical CS of concrete was gained by multiplying the experimental cube strengths by 0.8, again using Eurocode 222.

Idealized stress–strain diagrams in Eurocode 222 concrete and reinforcing steel.

Test results and discussion

In this section of the study, the flexural behavior of RC Beams is examined in detail. For this aim, bending RC Beams are designed with different longitudinal reinforcement and WGP amounts. Comparisons are then presented.

Effect of the amount of longitudinal reinforcement on bending capacities of samples

To examine how longitudinal reinforcement affects RC beam bending, three different quantities were used. RC beam Ф12_ GP0% symbolizes an RC beam with a WGP content of 0% and a longitudinal bar selected as Ф12. Details of the experimental program are presented in the following parts.

Situation 1: Fracture and load-bending behavior of RC beam (Ф12_B_GP1_0%, Ф10_B_GP2_0%, Ф8_B_GP3_0%)

The effect of varying amounts of the longitudinal bar on the fracture and collapse behavior of the RC Beams was investigated. For this aim, the diameters of the longitudinal bar were chosen as Ф8, Ф10, and Ф12, while WGP was chosen as a constant 0% replacement in RC beam. As depicted in Fig. 7, the load–displacement relationships of the RC beam samples were presented, and the fracture and collapse behavior of the RC Beams were identified. The test results showed that the maximum load–displacement (Pmax−δu) values were obtained as 50.85 kN and 23.45 mm, respectively, for the longitudinal bar selected as Ф12 (B_GP1). The longitudinal bar of Ф10 (B_GP2) leads to 46.72 kN and 27.83 mm for the maximum load–displacement values, respectively. It was observed that these findings decreased to 39.32 kN and 52.75 mm when the longitudinal bar diameter was reduced to Ф8 (B_GP3). As the effect of a longitudinal bar on the load–displacement capacities of RC beams is observed, as expected, as the longitudinal reinforcement diameter decreases, the load–displacement abilities of the RC Beams increasingly reduce as a significance of the reality of bending fracture in the RC Beams. Furthermore, the load–displacement capacity of Ф12_ B_GP1_0% was 8.8% and 29.3% greater than Ф10_B_GP2_0% and Ф8_ B_GP3_0%, correspondingly. This condition also caused the RC Beams to perform more flexibly as a result of reducing the quantity of tensile reinforcement. Fracture observations of the test beams at the final stage of the experimental study have been given in Fig. 8. In the event that the beam is inadequately reinforced, the reinforcement will fail first. Conversely, if the beam is excessively reinforced, the concrete will fail first. As a result, a beam that is under-reinforced is referred to as ductile, while a beam that is over-reinforced is brittle and can be easily damaged. When Fig. 7 is examined, it is observed that the beams exhibit ductile behavior, however, in Fig. 8, the ultimate damage mode of B_GP1 and B_GP2 beams is shear. Although this situation is sufficient in the beams, in beams having a high tensile reinforcement ratio, and small shear opening (shear strength demand is at the highest level due to close to a/d = 2.5), the demand for high shear deformation in a narrow distance while bending the beams is sufficient by the concrete due to not being met. The test beams (B_GP1 and B_GP2) in this condition were first forced to bend, and after reaching a certain ductility (pseudo-ductility) they were broken without shearing. Therefore, excess tensile reinforcement caused shear failure in beams as the ultimate damage. When Figs. 7 and 8 are examined, especially on B_GP3, both load–displacement and fracture behavior show that ductility has occurred clearly.

Situation 2: Fracture and load-bending behavior of RC beam (Ф12_B_GP4_10%, Ф10_B_GP5_10%, Ф8_B_GP6_10%).

In this part of the investigation, WGP in the RC beam is chosen as 10% as amounts of a longitudinal bar are selected as Ф8, Ф10, and Ф12 to consider the effect of changed numbers of the longitudinal bar on the fracture and collapse dispositions forms of the RC Beams. The load–displacement curves of the RC beam are presented in Fig. 9. The RC beam’s fracture and collapse behavior are shown. As shown in Fig. 10, for the longitudinal bar determined as Ф12 (B_GP4), the maximum load–displacement (Pmax−δu) was obtained as 50.32 kN, and 15.8 mm, respectively. As a result of the longitudinal bar chosen at Ф10 (B_GP5), the maximal load–displacement values were 46.24 kN and 22.22 mm. By reducing the diameter of the longitudinal bar to Ф8 (B_GP6), these findings decreased to 40.02 kN and 52.13 mm. As can be recognized from the load–displacement diagram in Fig. 9, the load–displacement capacity of the RC beam decreases for this WGP proportion. However, this decreases not much, differing from reference instances with no WGP. When Fig. 10 is examined, direct shear damage occurred in B_GP4 and B_GP5 test beams with WGP additive without bending damage. However, shear damage occurred after significant bending damage was detected in B_GP1, especially B_GP2. This indicates that 10% WGP contributes to shear damage behavior. When considering reinforcement changes from Ф12 (B_GP4) to Ф8 (B_GP6), the decrease proportion was obtained as 8.1% (B_GP5) and 20.5% (B_GP6), respectively. Furthermore, it was found that as the WGP ratio increased from 0 to 10%, the maximum load-carrying value of RC beam increased by 1.78% for B_GP6 and decreased by approximately 1.04% for B_GP4 and 1.03% for B-GP5. In other words, characteristic shear failure depending on limited/insufficient ductility was appointed in Ф12_ B_GP4_10% and Ф10_ B_GP5_10% test beams. However, as Ф8_ B_GP6_10% test beam provided adequate deformation capacity until the maximum load, beyond this load, it consisted of flexural failure.

Situation 3: Fracture and load-bending behavior of RC beam (Ф12_B_GP7_20%, Ф10_B_GP8_20%, Ф8_B_GP9_20%)

WGP ratio in RC beam remained at 20% despite variations in longitudinal bar diameters Ф8, Ф10, and Ф12. As offered in Fig. 11, the load–displacement records of RC beam were presented to investigate the fracture and collapse behavior of the RC Beams. As observed in Fig. 11, the maximum load-carrying capacity and ultimate displacement for the longitudinal bar selected as Ф12 (B_GP7) were obtained as 51.95 kN, and 12.56 mm, respectively. In cases where the longitudinal bar was selected as Ф10 (B_GP8) and Ф8 (B_GP9), these values were determined as 41.82 kN-11.46 mm and 37.63 kN-29.49 mm, correspondingly. As can be recognized from the load–displacement diagram in Fig. 11, the maximum load-carrying value of RC beam for the B_GP7 decreases by 19.50% and 27.56% according to B_GP8 and B_GP9 as the longitudinal bar diameter enhanced from Ф8 to Ф12. In other words, the damage form changed from bending rupture to shear rupture type. That is, as observed in Fig. 12 characteristic shear damage occurred in B_GP7 and B_GP8 test beams, while the B_GP9 test beam provided satisfactory ductility up to the 25 mm displacement value, but after this value, shear damage occurred and deformed. This indicated that the 20% WGP contribution restricted the ductility of B_GP9. However, sufficient ductility can be achieved since shear fracture occurs after crushing in the concrete compression zone.

Situation 4: Fracture and load-bending behavior of RC beam (Ф12_B_GP10_30%, Ф10_B_GP11_30%, Ф8_B_GP12_30%)

In this part, the longitudinal bar diameters of Ф8, Ф10, and Ф12 were chosen, and the WGP content in RC beam was set at 30%. Figure 13 shows the load–displacement observations of the RC beam tests, and the RC beam fracture and collapse behaviors were determined. As observed in Fig. 13, the maximum load level and ultimate deformation values for the longitudinal bar elected as Ф12 (B_GP10) were obtained as 42.90 kN and 12.53 mm, respectively. When longitudinal rod diameters of Ф10 (B_GP11) and Ф8 (B_GP12) were employed, these values were measured as 38.51 kN-16.98 mm and 33.98 kN-12.96 mm, correspondingly. Collated to the reference test beams (Ф12_ B_GP10_30%, Ф10_ B_GP11_30%, Ф8_ B_GP12_30%), considering tensile reinforcement changes from Ф12 to Ф8, the proportion of the maximum load-carrying capacity decrease was detected as 10.23% (B_GP11) and 20.79% (B_GP12), respectively. All test beams with a WGP ratio of 30% are shown in Fig. 13. As observed in Fig. 14, shear damage occurred in the samples. Therefore, 30% was considered the upper limit for the WGP ratio that should be used in this experimental investigation. If a larger amount of WGP ratio is used, both the load-carrying capacity of the beams decreases, and collapse occurs due to shear failure.

Based on the findings presented above, it has been noticed that the load–displacement capabilities of RC Beams steadily decrease when the diameters of the longitudinal bars reduce. Based on this information, it is apparent that the diameters of the longitudinal bars significantly impact the load–displacement capabilities of RC beams. It was observed that these effects were comparable to those that occurred in Situation 1, Situation 2, and Situation 3. It has been shown that when the WGP ratio decreases, load values closer to the reference sample are found. The fact is a statement that when comparing the load-bearing capabilities of RC beams to the reference sample in RC beam specimens with the diameters of the longitudinal bars, the addition of 10%, 20%, and 30% WGP decreased the abilities. This is because the WGP is excessively flat, which results in ruptures and reduces the amount of adhesion that exists between the WGP and cement paste. The reason for this is that the binding strength between the WGP and cement paste decreases.

Effect of various amounts of WGP on flexural behaviour of RC beam

This section evaluated RC beam sample bending behavior with different WGP percentages. Various reinforcement diameters (Ф8, Ф10, and Ф12) were evaluated with WGP weight ratios of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%. Detailed information is presented following subdivisions.

Situation 1: Fracture and bending behavior of proportion of WGP for 2Ф12 longitudinal bar

Various quantities of WGP were tested on RC beams for fracture and collapse behavior. Test specimens included 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% WGP with a fixed 2 Ф12 longitudinal bar. As shown in Fig. 15, the maximum load and ultimate displacement values for 0% WGP (B_GP1 were 50.85 kN and 23.45 mm, respectively. When WGP ratio was 10% (B_GP4), these values were 50.32 kN and 15.80 mm. With a 20% WGP ratio (B_GP7), these values were 51.95 kN and 12.56 mm. Finally, using a 30% WGP ratio (B_GP10), 42.90 kN and 12.53 mm were obtained. Furthermore, as can be observed from the load–displacement curves in Fig. 15, there were noticeable bending fractures in the RC beam test samples. As related to these states for the 2Ф12 longitudinal bar in the RC beam, it can be observed that as the proportion of the WGP enhanced from 0 to 30%, the load capacity of the RC beams progressively reduced due to rising the WGP amount and forthcoming presence of shear ruptures in the RC beams as offered in Fig. 16.

Situation 2: Fracture and bending behavior of proportion of WGP for 2Ф10 longitudinal bar

In all test specimens, 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% WGP levels were selected together with fixed 2Ф10 longitudinal reinforcements to investigate the impact of varying WGP amounts on the fracture and collapse behavior of RC Beams. Figure 17 shows the load–displacement curves. A maximum load of 46.72 kN and a ultimate displacement of 24.83 mm were found for the WGP ratio (B_GP2) chosen as 0%, as shown in Fig. 17. At 10% WGP rates (B_GP5), these values were 46.24 kN and 22.22 mm. These results were 41.82 kN and 11.46 mm, respectively, when WGP rates were used as 20% (B_GP8). Ultimately, these results went down to 38.51 kN and 16.98 mm, respectively, when the WGP ratio reached 30% (B_GP11). As observed from the test results for different amounts of WGP (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%), Fig. 18 presents that bending failures occurred in the B_GP2 test specimen. However, an experimental study shows that while no bending-induced damage occurred in the other test beams (B_GP5, B_GP8, B_GP11), shear-induced ruptures resulted. Regarding these conditions for the 2Ф10 longitudinal bar in RC beam, it can be noticed that with the increase of WGP ratio from 0 to 30%, the load–displacement capacities of RC Beams gradually decrease by 1% (B_GP5), 10.4%. (B_GP8) and 17.5% (B_GP11).

Situation 3: Fracture and load behavior of the proportion of WGP for 2Ф8 longitudinal bar

To assess the impact of various WGP ratios on the flexural performance of RC Beams, longitudinal bars in the RC beam specimens were fixed at 2Ф8. WGP proportions of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% were employed. According to Fig. 19, for the WGP proportions used as 0% (B_GP3), the maximum load level was measured as 39.32 kN, and the ultimate displacement was detected as 52.75 mm. At 10% WGP (B_GP6), these values were 40.02 kN and 52.13 mm. Results reduced to 37.63 kN and 29.49 mm when WGP was raised to 20% (B_GP9). Finally, increasing the WGP ratio to 30% (B_GP12) decreased these values to 33.98 kN and 12.96 mm. Examining the test results for different amounts of WGP (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%), Fig. 20 shows that bending damages were observed in RC Beams. As mentioned above, as related to these conditions for 2Ф8 longitudinal bar in the RC beam, it might be detected that as the percentage of the WGP enhanced from 0 to 30%, the maximum load-carrying capabilities of the RC Beams increasingly curtailed except for 10% WGP due to the forthcoming presence of shear ruptures in RC Beams. As a result, the ultimate damage in beams with WGP (0% (B_GP3), 10% (B_GP6), 20% (B_GP9)) except B_GP12 with a WPG ratio of 30% is due to bending.

The load–displacement curves and mechanical properties of the twelve RC Beams are presented in Table 3. In comparison to all RC beam samples, B_GP3 and B_GP6 exhibited the highest displacement values, as anticipated, as a result of the reinforcement bar’s size and content. The values of displacement and rigidities at Pmax and Py are also presented in Table 3. In addition, the deformation values corresponding to these values are also given in detail. The presence of WGP used up to 10% reduces the maximum and ultimate loads developed at similar intervals. However, It has been observed that excess WGP used beyond 10% leads to a decrease in maximum loads. It may also be detected from Table 3 that the Pmax and Py experimental test consequences of the B_GP5 were the minimum influenced as a result of the addition of 10% WGP, and this condition might be recognized as the reducing tensile reinforcement contents of the RC Beams compared to the other RC beam test beams. Up to 10% of WGP can adequately support the load with an ϕ8 tension bar. In the previous investigations, it was indicated the reasons. As one of these reasons, it was detected that a weak construction was observed among the WGP and the cement matrix. This was observed due to the decrease in connection strength between the WGP and the cement paste and the great flatness of WGP. Thus, it caused ruptures and decreased adherence between WGP and cement paste23. The other reason is that as the content of WGP increases, the ratio of ruptures and holes increases in the concrete’s matrix19. It has been observed that rigidities tend to decrease depending on the amount of WGP and the results obtained are compatible with literature research.

Evaluation of energy dissipation and ductility

At the end of each experiment, a load–displacement curve of each test specimen was drawn. The sum of the areas under the curve represents the total energy consumed by the test beams. It is known that the sum of the different areas under the curve represents different energy consumption. Therefore, the area constituting the near-linear part of the curve and limited to 85% of the maximum load (0.85Pmax) represents the elastic energy consumption. Similarly, the area is limited by the maximum load (Pmax) representing the test beams’ energy consumption at the maximum load value. When the elastic energy consumption value is subtracted from the total area under the curve, the plastic energy consumption value of the sample is obtained. Elastic, plastic, and total energy consumption can be determined by considering each sample’s area under the load–displacement curve. The ductility coefficient, which is directly related to energy consumption, is also a very important parameter. Because the reinforcement forming the sample, sample geometry and concrete strength affect the ductility. Therefore, the energy consumption capacity is also affected. The ratio of plastic displacement to elastic displacement (δu/δy) corresponding to the 0.85Pmax value of the sample is expressed as the ductility ratio. If the ductility ratio is among 4–5 in beams designed as under-balanced, it is stated that sufficient displacement is provided. Table 4 presents the experimentally established energy dissipation capacities of the RC Beams. As observed from Table 4, B_GP6 exhibited a maximum total energy dissipation of 1.96 kJ throughout the testing procedures. 10%, 20% and 30% WGP added to the test beams caused a decrease in elastic energy consumption capacity. When the energy dissipation (EPmax) values were compared, the following results were obtained. The reduction compared to B_GP1 was obtained as 27.91% in B_GP4 (from 0.43 to 0.31 kJ), 11.63% in B_GP7 (from 0.43 to 0.38 kJ), and 39.54% in B_GP10 (from 0.43 to 0.26 kJ). The reduction compared to B_GP2 was 37.50% in B_GP5 (from 0.80 to 0.50 kJ), 65.04% in B_GP8 (from 0.798 to 0.279 kJ), and 65.00% in B_GP11 (from 0.80 to 0.28 kJ). Finally, the decrease compared to B_GP3 was obtained as 83.85% in B_GP6 (from 1.61 to 0.26 kJ), 86.34% in B_GP9 (from 1.61 to 0.22 kJ), and 91.93% in B_GP12 (from 1.61 kJ to 0.13 kJ). This indicates that the energy consumption at maximum load decreases as the tension reinforcement decreases and the WGP ratio improves. Failure observation of all test beams was given in Fig. 21.

Image processing method

In this part of the study, the formation of cracks/microcracks on the RC beam surface during the experiment was tried to be examined using the DIC method. The cracks measured with the DIC technique will then be tested and compared with the findings from the experiments. One of the main aims of this study is to demonstrate that image processing can early detect cracks in concrete that are invisible to the human eye. As a result, it will be shown that the image processing approach that was used in this study has the potential to be an effective tool for both destructive and non-destructive testing procedures.

Image processing is performed to enhance an image or examine its important data. Image processing methods have recently become preferred to identify micro and macro damages that will occur in RC Beams. To obtain image processing, RC Beams were painted white for easy detection of ruptures during imaging. As presented in Fig. 22, a camera, a light source (80w Led), and a computer for saving the image were used to obtain the image during the experimental tests. RC beam, photographs of the test samples were taken with the help of a 24.2 Megapixel digital camera during the experimental test until the final loading stage (without any contact with the surface of the test sample). The digital camera was fixed on a tripod by its axis perpendicular to the space of attention. Furthermore, the image capture speed of the digital camera was set to take an image every 4 s. External lighting was focused on the section of attention to improve the images.

The grid displacements gained from digital pictures are converted into the actual displacement of the RC beam test piece as detected in Fig. 22. The color variant produced Y-direction displacement in Fig. 23, demonstrating that the lower part of the RC beam has maximum negative values. This statement approves the deviation of the real RC beam test beam while it is under loadings, as presented in Fig. 23. Reference points taken on the RC beam while imaging is presented in Fig. 23a. While the loading reaches collapse load, the bottom of the angular displacement figure demonstrates an apparent dividing line.

Furthermore, as detected in Fig. 24, the test piece digital image demonstrates the existence of minor cracking on the RC beam surface depending on the strain values. Furthermore, the diagram also reveals that the cracking has speared the RC beam test specimen. While the test beam is subject to collapse loading, it is cracked, as presented in Fig. 24, and the location of the damage is similar to the location of potential damage previously noticed during the loading phase. Figure 24 also demonstrates that all strains are consistently distributed, representing that the rupture has not yet been established in the RC beam test beam while the load is applied. While the load is incrementally increased, the strain figure displays minor strain concentration at the RC beam bottom in the y direction. It has been determined that when the loading is increased, ruptures that cannot be observed with the naked eye occur and can be observed in the figure. Figure 24 displays that the strain concentration for the RC beam test beam subject to collapse loading follows at the same location roughly as for the RC beam test beam dependent on smaller loadings and that the strain concentration proceeds over the entire RC beam test beam surface. The strain diagram demonstrates the 45° direction for all strain capabilities matching the digital display shown in Fig. 24, thus causing test piece fracture to shear based on the strain diagram. At completion of picture analysis, as detected in Fig. 25, evaluation of the displacement values obtained from experimental tests and image processing are given. As observed in Fig. 25, the values obtained from experimental tests and image processing gave similar results.

Conclusions

This research work focused on the effect of using different diameter longitudinal reinforcement and different amounts of WGP ratio on the flexural performance of RC Beams. For this purpose, WGP was added to RC Beams with varying longitudinal reinforcements (Φ8, Φ10, and Φ12) at varying rates (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%). 12 test samples were examined using the above-mentioned longitudinal reinforcement and WGP amount. Moreover, the DIC technique was used to identify the cracks/micro-cracks in RC Beams, and test results were verified with the aid of the DIC technique. The findings obtained as a result of the investigation are summarized as follows:

-

When compared based on 0% WGP and ρs = 0.0174, i.e. Φ12, the WGP ratio of the experimental test beams of 10%, 20% and 30% decreased by 1.0% and 15.6%, respectively, and increased by 2.1%. According to 0% WGP and ρs = 0.0121 i.e. Φ10, the maximum load of the WGP ratio of the experimental test beams of 10%, 20%, and 30% decreased 1.0%, 10.5%, 17.6%, respectively. Compared to ρs = 0.0077 i.e. Φ8 and 10% WGP, while there was an increase of 1.8% in 10%, there was a decrease of 4.3% and 13.6% in 20% and 30%, respectively.

-

Despite an increase in WGP content to 10%, there was no notable reduction in CS relative to the reference concrete. It was discovered that, in comparison to the reference mixture, the test beams’ capacity steadily declined as the WGP ratio increased after the 10% level. This is because the bond strength between the WGP and the cement paste decreases due to the WGP being too flat, thus causing ruptures and reduced adherence between the WGP and the cement paste.

-

When more than 10% of the cement weight WGP was used, ductility and energy loss due to excessive amount were observed to be detrimental to the test results.

-

The structural performance of the tested RC Beams increased with the increase in first rupture and ultimate load capacity and the incorporation of WGP, respectively. This was combined with a reduction in the deformation that corresponds to the first rupture and ultimate load separately.

-

There is an agreement between analytical calculations and experimental results. Comparing the analytical calculations to experimental results of the reference, ρs = 0.0174 i.e. Φ12, ρs = 0.0121 i.e. Φ10 and ρs = 0.0077 i.e. Φ8 test beams, approximations of 21.1%, 8.1%, and 7.9% changes were gained, respectively. While ρs = 0.0174 i.e. Φ12, ρs = 0.0121 i.e. Φ10 and ρs = 0.0077 i.e. Φ8 with 10% WGP ratio, 21.7%, 8.8%, and 9.7% approaches were gained, respectively, while this ratio was 16.8% for ρs = 0.0174 i.e. Φ12, 19.6% for ρs = 0.0121 i.e. Φ10 in test beams containing 20% and 30% WGP, respectively. It was gained as 4.4% for ρs = 0.0077 i.e. Φ8 with 20% WGP ratio, 17.4% for ρs = 0.0174 i.e. Φ12with 30% WGP ratio, 22.5% for ρs = 0.0121 i.e. Φ10 with 30% WGP ratio, and 2.5% for ρs = 0.0077 i.e. Φ8 with 30% WGP ratio.

-

At completion of image processing, it was observed that closer consequences between the values obtained from experimental tests and image processing. Furthermore, consequences offered that the image processing might obtain concrete external ruptures even earlier dark crack lines noticeable to the naked eye appear. it was measured that the image processing technique that was used in this study might be a supporting tool to destructive and non-destructive testing methods.

Recommendations

Current research indicates that WGP can be used as a local eco-material, an economical material that is convenient, easy to obtain in large quantities, economical and ecologically sensitive, and can be chosen for concrete construction. Since there is a lack of information on the flexural behavior of concrete produced with multiple recycled materials, future research will focus on using WGP in combination with other recycled materials. The next phase of this work will address how glass particle size, replacement %, and morphology affect concrete consistency.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WGP :

-

Waste glass powder

- RC Beams :

-

Reinforced concrete beams

- DIC :

-

Digital image correlation

- CA :

-

Coarse aggregates

- FA :

-

Fine aggregates

- c :

-

The neutral axis depth (mm)

- ε c :

-

The strain of concrete

- εs :

-

The strain of tensile reinforcement

- εs′:

-

The strain of compressive reinforcement

- d :

-

The effective depth (mm)

- d' :

-

The distance from the center of the compression reinforcement to the outermost concrete fiber (mm)

- F s :

-

The forces in the tensile reinforcement

- F s′:

-

The forces in compressive reinforcement

- F c :

-

The compressive force in concrete (N)

- r :

-

The moment arm (mm)

- σ c :

-

The compressive stress in concrete

- P max :

-

The maximum bearing load of the beam

- a:

-

The shear span

- CS :

-

Compressive strength

- f ck :

-

The cylinder compressive strength of concrete

- f yk :

-

The yield strength of steel

References

Aslam, F. et al. Evaluating the influence of fly ash and waste glass on the characteristics of coconut fibers reinforced concrete. Struct. Concr. 24, 2440–2459 (2023).

Paul, D., Bindhu, K. R., Matos, A. M. & Delgado, J. Eco-friendly concrete with waste glass powder: A sustainable and circular solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 355, 129217 (2022).

Perez, O. F. A., Florez, D. R., Vergara, L. M. Z. & Benavides, K. V. H. Innovative use of agro-waste cane bagasse ash and waste glass as cement replacement for green concrete. Cost analysis and carbon dioxide emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 379, 134822 (2022).

Althoey, F. et al. Effect of fly ash and waste glass powder as a fractional substitute on the performance of natural fibers reinforced concrete. Ain Shams Eng. J. 102247 (2023).

Singh, S. Partial replacement of coarse aggregate with waste glass in concrete. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 6, 6723–6728 (2017).

Adaway, M. & Wang, Y. Recycled glass as a partial replacement for fine aggregate in structural concrete–Effects on compressive strength. Electron. J. Struct. Eng. 14, 116–122 (2015).

Hama, S. M., Mahmoud, A. S. & Yassen, M. M. in Structures. 510–518 (Elsevier).

Ramakrishnan, K., Pugazhmani, G., Sripragadeesh, R., Muthu, D. & Venkatasubramanian, C. Experimental study on the mechanical and durability properties of concrete with waste glass powder and ground granulated blast furnace slag as supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 739–749 (2017).

Haido, J. H., Zainalabdeen, M. A. & Tayeh, B. A. Experimental and numerical studies on flexural behavior of high strength concrete beams containing waste glass. Adv. Concr. Constr. 11, 239–253 (2021).

Yassen, M. M., Hama, S. M. & Mahmoud, A. S. Shear behavior of reinforced concrete beams incorporating waste glass powder as partial replacement of cement. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 27, 2194–2209 (2023).

Elsayed, M., Abd-Allah, S. R., Said, M. & El-Azim, A. A. Structural performance of recycled coarse aggregate concrete beams containing waste glass powder and waste aluminum fibers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01751 (2023).

Bayar, G. & Bilir, T. A novel study for the estimation of crack propagation in concrete using machine learning algorithms. Constr. Build. Mater. 215, 670–685 (2019).

Kim, H., Ahn, E., Cho, S., Shin, M. & Sim, S.-H. Comparative analysis of image binarization methods for crack identification in concrete structures. Cem. Concr. Res. 99, 53–61 (2017).

Rimkus, A., Podviezko, A. & Gribniak, V. Processing digital images for crack localization in reinforced concrete members. Proced. Eng. 122, 239–243 (2015).

Rimkus, A. & Gribniak, V. Experimental investigation of cracking and deformations of concrete ties reinforced with multiple bars. Constr. Build. Mater. 148, 49–61 (2017).

Fayyad, T. M. & Lees, J. M. Application of digital image correlation to reinforced concrete fracture. Proced. Mater. Sci. 3, 1585–1590 (2014).

Zeybek, Ö. et al. Shear performance in reinforced concrete beams with partial aggregate substitution using waste glass: A comparative analysis via digital imaging processing and a theoretical approach. ACS Omega 9, 41662–41675. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c05655 (2024).

Karalar, M. et al. Utilizing recycled glass powder in reinforced concrete beams: Comparison of shear performance. Sci. Rep. 15, 6919. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91493-z (2025).

Zeybek, Ö. et al. Influence of replacing cement with waste glass on mechanical properties of concrete. Materials 15, 7513 (2022).

Elaqra, H. A., Haloub, M. A. A. & Rustom, R. N. Effect of new mixing method of glass powder as cement replacement on mechanical behavior of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 203, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.077 (2019).

Muhedin, D. A. & Ibrahim, R. K. Effect of waste glass powder as partial replacement of cement & sand in concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02512 (2023).

Standard, B. Eurocode 2: Design of concrete structures. Part 1, 230 (2004).

Shayan, A. & Xu, A. Performance of glass powder as a pozzolanic material in concrete: A field trial on concrete slabs. Cem. Concr. Res. 36, 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2005.12.012 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for the financial support provided for this research by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, through Large Groups RGP2/539/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, YOÖ, ÖZ and MK; methodology, YOÖ, ÖZ, MK and CA; data curation, YOÖ; investigation, YOÖ, BB, MK and ÖZ; validation, YOÖ, ÖZ, ES and OAU; visulation, BB, EA, AB, SS, ES, and OAU; Writing-original draft preparation, YOÖ, MK, CA, AB, SS, BB, ES, EA and OAU; writing-review and editing, YOÖ, MK, BB, ÖZ, CA, EA, AB, SS, ES, and OAU; funding acquisition, EA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aksoylu, C., Başaran, B., Karalar, M. et al. Experimental, theoretical and digital image correlation methods to assess bending performance of RC beams with recycled glass powder replacing cement. Sci Rep 15, 25163 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08710-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08710-y