Abstract

The increasing number of contact lens users correlates with a rise in the incidence of fungal keratitis. Fungal keratitis can lead to blindness if not treated promptly, and its early symptoms are similar to those of bacterial and amoebic keratitis, making rapid diagnosis challenging. This study aimed to assess the potential of using a peptide antibody against the fungal-specific protein ERG24, which encodes sterol C-14 reductase, to differentiate fungal keratitis from other forms of keratitis. The specificity of the ERG24 antibody was assessed through Western blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Immunocytochemistry (ICC) was performed by co-culturing two types of fungi, Acanthamoeba, and two bacterial strains with human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells. Additionally, to evaluate the diagnostic potential of the ERG24 antibody, animal models of fungal, amoebic, and bacterial keratitis were developed, and ELISA was conducted on tear and ocular lysates from these models. The results demonstrated that the antibody specifically reacted with Fusarium solani in Western blot, and both ELISA and ICC confirmed that the ERG24 antibody did not react with HCE cells, Acanthamoeba, or bacteria, but was specific to the two fungal species. In vivo experiments further showed that the ERG24 antibody significantly detected F. solani in tear-wash samples and eyeball lysates from the fungal keratitis model, without reacting with samples from amoebic and bacterial keratitis models. This study suggests that the ERG24 peptide antibody could provide valuable information for developing differential diagnostic methods for fungal keratitis compared to other forms of keratitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fungal keratitis (FK) is a corneal infection that can progress to corneal ulceration and, in severe cases, result in blindness if not diagnosed and treated promptly1,2. Since the first reported case in 1897, the incidence of FK has increased, with estimates suggesting over 1 million cases occur globally each year3. More than 100 fungal species are known to cause FK, with the most frequently reported pathogens in humans belonging to the genera Fusarium spp., Aspergillus spp., and Candida spp3,4. Among these, infections caused by filamentous fungi such as Fusarium and Aspergillus are particularly common and can lead to serious clinical outcomes3.

The principal etiological factors contributing to FK include ocular trauma, contact lens wear and improper care, immunosuppression, and ocular surgery. Since the 1980s, contact lens wear has been increasingly recognized as a significant risk factor for FK. The rise in contact lens usage has been correlated with an increased incidence of FK1,5,6,7. FK associated with contact lens usage may arise from fungi, Acanthamoeba, and bacteria. The early clinical manifestations, such as redness, blurred vision, and ocular pain, are common across these infections, complicating the differential diagnosis between FK, Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK), and bacterial keratitis (BK)2. Management of FK requires prolonged treatment with suitable topical and systemic antifungal agents8. However, in many regions, treatment is impeded by the limited commercial availability of antifungal drugs, rising drug resistance, low ocular bioavailability and residence time, and inadequate penetration of ocular tissues9. Delays in diagnosis can lead to deeper fungal infiltration into corneal tissues, exacerbating treatment challenges9. Consequently, the development of rapid and accurate diagnostic methods is imperative to prevent treatment delays and potential vision loss.

Currently, the diagnostic modalities for FK encompass culture of corneal scraping, histopathological examination, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM). Nevertheless, the culture of corneal scraping and histological assessments are time-intensive, and corneal scraping procedures may induce discomfort in patients. Additionally, PCR is susceptible to false-positive results, while IVCM requires expert interpretation2. Consequently, there is a pressing demand for a non-invasive diagnostic approach that facilitates the facile, rapid, and precise diagnosis of FK.

To diagnose Scedosporium species, which are pathogenic fungi in humans, a rapid and sensitive lateral-flow device has been developed using a Scedosporium-specific monoclonal antibody known as HG1210. This antibody binds to extracellular polysaccharide antigens present on the spore and hyphal cell walls of these fungi, which are secreted during hyphal growth. Building on this finding, it was hypothesized that generating antibodies against secretory fungal proteins could enable the detection of fungal antigens in the tears of patients with fungal keratitis (FK). This approach offers the advantage of being non-invasive, allowing for a painless and swift diagnostic procedure that eliminates the need for the presence of medical personnel. Previous studies have demonstrated that differential diagnosis of AK utilizing Acanthamoeba-specific antibodies is feasible11,12,13,14. We hypothesized that a similar approach could be applied to the diagnosis of FK through the use of fungi-specific antibodies. Consequently, we investigated proteins that are specifically expressed or secreted by fungi, which could serve as suitable candidates for antibody production.

Ergosterol is a sterol abundantly present in the membranes of fungi and protozoa, functionally analogous to cholesterol in mammalian cell membranes15. The ERG24 gene encodes C-14 sterol reductase, which is localized on the endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane, catalyzing the reduction of 4,4-dimethylcholesta-8,14,24-trienol to 4,4-dimethylzymosterol16.

Glabridin, an antifungal agent, compromises cell membrane integrity by inhibiting ERG24, a protein that plays a critical role in ergosterol biosynthesis17. This inhibition disrupts the production of ergosterol, an essential component of fungal cell membranes, thereby affecting the membrane’s integrity and function. Given that ERG24 is a crucial protein for fungi and a target of antifungal drugs, we selected ERG24 as a candidate for antibody production. This selection aims to leverage the specific targeting of ERG24 to develop antibodies that could aid in the detection and diagnosis of fungal infections, enhancing the efficacy of antifungal treatments.

In this study, we generated Fusarium-specific antibodies targeting ERG24 and evaluated their diagnostic potential for FK. The findings of this study contribute to the advancement of antibody-based diagnostic methods for FK, potentially improving the early detection and treatment of this condition.

Materials and methods

Ethics declaration

All experimental methods were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations set out by Kyung Hee University IACUC. All experimental protocols were approved by the Kyung Hee University IACUC (permit number: KHSASP-24-375). All of the methods and experimental procedures were carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Cell cultures

Fusarium solani (NCCP 32678), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (NCCP 16091), and Staphylococcus aureus (NCCP 15920) were obtained from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Osong, Republic of Korea). Aspergillus fumigatus (KCTC 6145) was obtained from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (Jeongeup, Republic of Korea), and Acanthamoeba castellanii (ATCC 30868) and human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells (ATCC PCS-700-010) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). F. solani and A. fumigatus were cultured in Sabouraud Dextrose (SD) medium at 37 °C for 3 days. A. castellanii was cultured in peptone-yeast-glucose (PYG) medium at 25 °C for 5 days. HCE cells were aseptically cultured in keratinocyte growth medium (KGM BulletKit™; Lonza, Portsmouth, NH, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus were cultured in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium at 37 °C for 1 day.

Peptide antibody production of ERG24 protein

The highly antigenic region of the ERG24 protein was identified through an analysis of its secondary structure. ERG24 peptides with the sequence NH2-KQVYGTKLRESGRPLEYRF-COOH were selected as immunogens. Two New Zealand White rabbits were intradermally immunized with 1.0 mg of peptide-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) in complete Freund’s adjuvant on day 0. Subsequent immunizations were performed on days 27 and 35 with 0.5 mg of the peptide in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. Following the second immunization, antibody titers were evaluated using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), employing the peptide conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the coating antigen, until the titers stabilized. After the final immunization, blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture from each rabbit (GW Vitek, Seoul, Republic of Korea). All experimental procedures were carried out by GW Vitek (Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Western blot

To confirm the specificity of the ERG24 antibody, Western blotting was performed. The protein samples used in this study included cell lysates from F. solani, A. fumigatus, A. castellanii, HCE cells, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus. Cell lysates were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST (25 mmol/L Tris base, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 2 h. After blocking, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with ERG24 antibodies at a 1:1,000 dilution. Following incubation, the membrane was washed with TBST and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a 1:2,000 dilution. Protein bands were visualized using Clarity Enhanced Chemiluminescence reagent (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and imaged on a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISA was performed to evaluate the antibody responses specific to the F. solani ERG24-antibody and to determine the lowest detectable concentration of Fusarium antigens. Antigens and sera were serially diluted, ranging from 100 to 0.001 µg/ml and 1:5 to 1:5,000, respectively. Ninety-six-well plates were coated with antigen solution in carbonate buffer (0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 9.5) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After each incubation, the plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). Blocking was performed with 0.2% gelatin at 37 °C for 2 h. All antibody dilutions were prepared in PBST. The diluted samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by washing. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cusabio Co. Ltd, Wuhan, China) was then added at a 1:2,000 dilution and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. O-phenylenediamine (OPD; Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA) was prepared in citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.03% H2O2 and used as the substrate. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using the EZ Read 400 microplate reader (Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Sera from non-immunized rabbits served as the negative control. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times with similar results.

Immunocytochemistry

To confirm the specificity of the ERG24 polyclonal peptide antibody, immunocytochemistry was conducted. HCE cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well on sterile coverslips in a 6-well plate and cultured in KGM medium at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. The next day, A. castellanii trophozoites were added at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well and co-cultured with the HCE cells for 5 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. F. solani, A. fumigatus, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus were grown in liquid broth to the early exponential phase (OD600 = 0.8) and then co-cultured with the HCE cells and A. castellanii for 1 h. After co-culture, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with ice-cold 100% methanol for 5 min at room temperature (RT). The cells were then washed three times with PBS and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBST) for 5 min at RT. Following permeabilization, the cells were washed with PBS and blocked with blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin and 22.52 mg/mL glycine in PBST) for 30 min at RT. The cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with ERG24 polyclonal antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer. The next day, after washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG for 2 h at RT. After three additional washes with PBS, the cells were stained with VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8, Wetzlar, Germany).

Establishment of an animal model

A total of 19 eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from NARA Biotech (Seoul, Republic of Korea). F. solani and S. aureus were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min to collect a concentration of 1 × 106 cells, while A. castellanii trophozoites were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 3 min to collect a concentration of 1 × 105 cells. A commercial soft contact lens (Proclear 1-Day Contact Lenses, CooperVision, NY, USA) was cut into 2-mm circles using a hole punch. Each pellet was suspended in 20 µl of sterile PBS, which was gently overlaid on the surface of the contact lens and incubated at 25 °C for 1 h. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection (5 mg/mL ketamine and 1 mg/mL xylazine combined; 0.3 mL/20 g), and several incisions were made on the corneal surface using a 25-gauge syringe needle. After scratching the corneas of the mice, contact lenses containing F. solani, A. castellanii, and S. aureus were gently placed on the eyeballs, and eyelids were sutured with 6-0 nylon sutures (Woorimedical, Namyangju, Republic of Korea). Mice were monitored daily for 10 days to assess FK, AK, and BK development in the eyes. Euthanasia was carried out by administering Avetin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) anesthetic intraperitoneally at a dose of 0.23 ml per 10 g of mouse body weight. Sutures were opened at 10 days post-infection (dpi) for tear-wash samples and whole eyeball collection. Tear-wash samples were collected by inoculating 10 µl of cold sterile PBS into each eye infected with F. solani, A. castellanii, and S. aureus, and the whole eyeball was homogenized in 500 µl of sterile PBS. Naïve mice were also sampled after anesthesia and used as negative controls. All samples were immediately frozen and stored at -80 °C until use.

Detection of F. solani antigen in FK, AK, and BK mouse models using ERG24 peptide polyclonal antibodies

ELISA was conducted using ERG24 peptide polyclonal antibodies to identify the F. solani antigen in samples from FK, AK, and BK mouse models. Tear-wash samples (50 µg/ml) and whole eyeball lysates (50 µg/ml) were coated on a 96-well plate using a carbonate coating buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were then washed three times with PBST and subsequently blocked with 0.2% gelatin at 37 °C for 1 h. Plates were washed three more times with sterile PBST, and ERG24 peptide polyclonal antibodies were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cusabio Co. Ltd, Wuhan, China) was added at a dilution of 1:2,000 and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. OPD substrate was dissolved in citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.03% H2O2. Optical density at 450 nm was read using the EZ Read 400 microplate reader (Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Unimmunized rabbit serum was used as the negative control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 5 (San Diego, California, USA). The data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance between group means was indicated with asterisks. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the primary accession code KAJ4232303.1, Q4WKA5.1, Q4WJJ9.1, AMN14208.1, and AAH00054.1.

Results

Sequence analysis of ERG24 from F. solani for the purpose of antibody production

The ERG24 protein of Fusarium solani comprises 1,431 base pairs and encodes 476 amino acids, with a calculated molecular mass of 52.4 kDa (GenBank accession No. KAJ4232303.1). To design a peptide antigen with optimal antigenicity, the amino acid sequence of ERG24 from F. solani was compared with those from Aspergillus fumigatus, Acanthamoeba castellanii, and Homo sapiens using Clustal X version 2.1 (Fig. 1). Specific amino acids were selected for peptide antibody production, highlighted in the red-boxed area in Fig. 1. Sequence homology analysis revealed that ERG24 from F. solani shares 50.11%, 52.34%, 33.51%, and 30.35% similarity with ERG24A and ERG24B from A. fumigatus, D14-sr from A. castellanii, and DHCR7 from H. sapiens, respectively (Table 1).

Amino acid sequence alignments of ERG24 from various organisms. The ERG24 amino acid sequences from Fusarium solani (F.s_ERG24, KAJ4232303.1), Aspergillus fumigatus (A.f_ERG24A, Q4WKA5.1 and A.f_ERG24B, Q4WJJ9.1), Acanthamoeba castellanii (A.c_D14-sr, AMN14208.1), and Homo sapiens (H.s_DHCR7, AAH00054.1) were analyzed. Regions of sequence similarity are shaded, and a boxed region indicates the segment utilized for the production of the anti-ERG24 polyclonal antibody.

F. solani-specific antibody responses to ERG24 antibodies

To validate the specificity of anti-ERG24 antibodies, Western blot analysis was performed. The specificity of the ERG24 antibody was further corroborated through Western blot assays using cell lysates from F. solani, A. fumigatus, A. castellanii, human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the ERG24 antibody exhibited a robust interaction with F. solani (indicated by the arrowhead), while no interactions were detected with HCE cells or other keratitis-causing agents.

Western blot analysis of specific antibody response to ERG24 protein. The specificity of the anti-ERG24 antibody derived from F. solani was assessed by Western blot analysis using cell lysates from various organisms. Lane 1: F. solani, Lane 2: A. fumigatus, Lane 3: A. castellanii, Lane 4: HCE cells, Lane 5: P. aeruginosa, and Lane 6: S. aureus.

Antibody responses to ERG24 proteins

An ELISA was conducted to evaluate the IgG antibody responses of immunized rabbit sera to F. solani cell lysates and conditioned media (Fig. 3). The assay revealed that ERG24-specific IgG antibody responses were detectable in both the cell lysate and conditioned media of F. solani up to a 1:500 dilution (Fig. 3A,G). Moreover, the ELISA demonstrated strong antibody responses to the cell lysates and conditioned media of A. fumigatus (Fig. 3B,H). In contrast, antibody responses were not observed against other organisms (Fig. 3C–F). To determine the minimum detectable concentration of F. solani antigens, an ELISA was performed using immunized rabbit sera (Fig. 4). The detection thresholds for ERG24-specific IgG antibody responses were as low as 1 µg/ml for cell lysates (Fig. 4A) and 0.1 µg/ml for conditioned media (Fig. 4G) of F. solani. Similar detection levels were noted for A. fumigatus (Fig. 4B,H). These findings suggest that a robust anti-fungal antibody response can be elicited by sera immunized against F. solani ERG24.

Antibody titration of F. solani-specific anti-ERG24 polyclonal antibody. The ERG24 antibody was titrated using serial dilutions of sera (ranging from 1:5 to 1:5,000) against the cell lysates (A–F) and conditioned media (G–L) from various organisms: (A) and (G), F. solani; (B) and (H), A. fumigatus; (C) and (I), A. castellanii; (D) and (J), HCE cells; (E) and (K), P. aeruginosa; (F) and (L), S. aureus. The positive group (bold black line) utilized immune mouse sera, whereas the negative control (dotted black line) employed naïve mouse sera. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times with similar results. Asterisks denote statistical significance between the absorbance values of positive and negative sera at corresponding dilutions (**P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001).

Sensitivity assessment of F. solani-specific anti-ERG24 polyclonal antibody. The sensitivity of the ERG24 antibody was evaluated using serial dilutions of the cell lysates (ranging from 100 to 0.001 µg/ml) and conditioned media. The positive control (bold black line) utilized immune mouse sera, while the negative control (dotted black line) employed naïve mouse sera. The tested samples include F. solani (A,G), A. fumigatus (B,H), A. castellanii (C,I), HCE cells (D,J), P. aeruginosa (E,K), and S. aureus (F,L). Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between the absorbance values of positive and negative sera at respective dilutions (***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001).

Confirming the specificities of the ERG24 antibody against F. solani and A. fumigatus

To verify the specificity of the ERG24 antibody, immunocytochemistry was conducted. The ERG24 antibody specifically detected F. solani (red, indicated by the green arrows) and A. fumigatus (red, indicated by the yellow arrows) within co-cultured samples (Fig. 5). The nuclei of HCE cells and A. castellanii were stained with DAPI (blue) and showed no interaction with the ERG24 antibody. Additionally, antibody-antigen interactions were not observed in P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. These findings demonstrate that the ERG24 antibody can specifically detect fungal species.

Immunocytochemistry assay utilizing anti-ERG24 antibodies. F. solani, A. fumigatus, A. castellanii, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus were co-cultured with HCE cells. The co-cultured cells were sequentially probed with the ERG24 antibody and a CFL555-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (red), followed by staining with DAPI (blue) prior to fluorescence microscopy. Bright-field, DAPI, ERG24-antibody, and merged images were captured at 400X magnification. The black scale bar represents 10 μm.

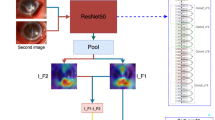

Production of FK, AK, and BK mouse models

To assess the antigen detection capability of the ERG24 antibody, mouse models for fungal keratitis (FK), Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK), and bacterial keratitis (BK) were developed. The methodology for creating these mouse models is illustrated in a simplified diagram (Fig. 6A). For inoculation with F. solani, A. castellanii, and S. aureus, the mouse cornea was scratched, followed by the placement and suturing of a contact lens containing each pathogen onto the mouse cornea. Lesions were observed at 10 days post-inoculation (dpi). Subsequently, the eyes were washed with PBS, tear-wash samples were collected, and eyeball lysates were obtained (Fig. 6B).

In vivo experimental design and detection of Fusarium antigens from fungal keratitis (FK), Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK), and bacterial keratitis (BK) mouse models. Keratitis was induced in BALB/c mice (n = 5 per group) by applying contact lenses infected with F. solani, A. castellanii, or S. aureus to scratched corneas for a duration of 10 days (A). Uninfected mice, serving as the control group (naïve, n = 5), were also included. Sutures were removed 10 days post-infection. Infected mice exhibited typical inflammation and keratitis symptoms compared to the naïve controls (B). Tear-wash samples and eyeballs were collected from all groups for further analysis. Fusarium antigens were detected using ERG24-specific antibodies via ELISA in tear-wash samples (C) and sonicated eyeball lysates in PBS (D). Symbols represent: Negative (open square), naïve tear-wash sample; Positive (closed square), FK-mouse tear-wash sample; (closed star), AK-mouse tear-wash sample; (closed inverted triangle), BK-mouse tear-wash sample. For eyeball lysates: Negative (open circle), naïve eyeball lysates; Positive (closed circle), FK-mouse eyeball lysates; (closed diamond), AK-mouse eyeball lysates; (closed triangle), BK-mouse eyeball lysates. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between the means (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

Detection of Fusarium antigens in experimental keratitis mouse models using the ERG24 antibody

The capability of the ERG24 antibody to detect Fusarium antigens was assessed using samples from fungal, Acanthamoeba, and bacterial keratitis mouse models. The ERG24 antibody specifically reacted with F. solani antigens in tear-wash samples (Fig. 6C) and eyeball lysates (Fig. 6D) from the FK mouse model. In contrast, tear-wash samples and eyeball lysates from the AK and BK models did not exhibit specific reactions with the ERG24 antibody. These findings indicate that the ERG24 antibody can specifically detect Fusarium antigens in the FK mouse model.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the potential of antibody-based differential diagnosis for fungal keratitis (FK). We generated a polyclonal antibody targeting the ERG24 protein of F. solani and confirmed its specificity for F. solani through ELISA, Western blotting, and immunocytochemistry (ICC) analysis. Moreover, the antibody demonstrated effective detection of F. solani antigens in tear-wash samples and eyeball lysates from a fungal keratitis mouse model.

Infectious keratitis can arise from various causes, but we specifically focused on keratitis frequently occurring in contact lens wearers, aiming to differentially diagnose fungal keratitis (FK), Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK), and bacterial keratitis (BK) in animal models. Previous studies have reported the development of four types of polyclonal antibodies against A. castellanii, all of which specifically detected Acanthamoeba antigens in samples from an AK mouse model18,19,20,21. In this study, we generated an antibody against F. solani and demonstrated its specific detection of Fusarium antigens in tear-wash samples and eyeball lysates from the FK mouse model (Fig. 6A,B). Furthermore, the Fusarium-specific antibody did not react with tear-wash samples or eyeball lysates from the Acanthamoeba and bacterial keratitis mouse models (Fig. 6C,D). This indicates that the antibody targeting F. solani ERG24 is highly specific and capable of distinguishing between Fusarium and Acanthamoeba.

Interestingly, the F. solani ERG24 antibody exhibited reactivity with antigens from both F. solani and A. fumigatus. These findings suggest that the antibody cannot differentiate between these two primary species responsible for fungal keratitis, likely due to the high sequence similarity between the ERG24 proteins of Fusarium and Aspergillus (Table 1). Consequently, while this antibody is unable to distinguish between different fungal species, it appears effective in differentiating fungal keratitis from Acanthamoeba keratitis and bacterial keratitis (Fig. 6). To enhance the Fusarium-specific diagnostic tool, it is necessary to develop monoclonal antibodies that can identify unique epitopes of the ERG24 antigen. To achieve differentiation and detection of Fusarium and Aspergillus antigens, a potential approach could involve the development and use of an Aspergillus-specific antibody. Additionally, considering that the antibody’s specificity has not been evaluated against Candida species-another significant causative agent of fungal keratitis-further research is warranted in this area.

In this study, we established an animal model of fungal keratitis to validate the specificity of the antibody as a potential candidate for developing diagnostic methods for fungal keratitis (FK). While other research groups have reported corneal infection models utilizing various fungal species, these typically involved establishing FK by scratching the cornea and either injecting F. solani with a syringe or directly smearing it onto the cornea3. In contrast to these methods, we induced FK by gently applying a soft contact lens coated with F. solani onto the mouse cornea following the induction of corneal injury (Fig. 6). This experimental approach more closely simulates the acquisition of FK in real-world scenarios among contact lens wearers, enhancing its potential applicability in future research aimed at developing novel diagnostic methods and treatments for contact lens-associated FK.

Recently, molecular diagnostic methods such as PCR and imaging techniques like in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) have been employed for the rapid diagnosis of FK22,23. Nonetheless, the most commonly used methods remain culturing or staining tissue biopsy specimens for microscopic examination24. These traditional techniques can cause significant discomfort to patients due to the requirement for corneal scraping to achieve a definitive diagnosis. Consequently, we hypothesized the necessity for a fast, painless, and straightforward method for FK diagnosis. The antibody developed in this study successfully detected Fusarium antigens in both corneal cells and tear samples from the FK animal model. Compared to conventional methods, this approach offers the advantage of reducing the time required for an accurate diagnosis while minimizing patient discomfort. However, given that the concentration of fungal antigens in tears may be low, further research is needed to enhance the sensitivity of FK diagnostic methods. In a previous study, a surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) immunoassay platform was developed for the early detection of Acanthamoeba keratitis25. This approach combined a monoclonal antibody developed against chorismate mutase, a secreted protein of A. castellanii, with immuno-SERS technology, enabling rapid and accurate detection of Acanthamoeba infections in human tear samples and contact lens solutions. We anticipate that employing this methodology will enhance the sensitivity of FK diagnostic approaches.

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Fusarium-specific antibodies, as demonstrated here, failed to differentiate between Fusarium and Aspergillus, possibly due to the presence of conserved sequences. However, their cross-reactivity has not been evaluated against other clinically relevant fungal pathogens associated with FK, particularly species within the genus Candida. Therefore, generalizing the diagnostic utility of Fusarium-specific antibodies for FK would be premature and potentially misleading. Additionally, during western blot analysis, loading controls could not be included due to species diversity. The absence of a universally conserved protein across all soluble lysates tested here precluded normalization of band intensities, rendering any quantitative comparisons inherently limited. As such, these findings must be interpreted with caution.

In summary, the antibody targeting ERG24 of F. solani successfully detected specific antigens in eyeball lysate and tear-wash samples from the Fusarium-induced keratitis mouse models. These findings could significantly contribute to the development of a rapid and non-invasive antibody-based diagnostic method for fungal keratitis.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the primary accession code KAJ4232303.1, Q4WKA5.1, Q4WJJ9.1, AMN14208.1, and AAH00054.1 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein).

References

Ting, D. S. J., Ho, C. S., Deshmukh, R., Said, D. G. & Dua, H. S. Infectious keratitis: an update on epidemiology, causative microorganisms, risk factors, and antimicrobial resistance. Eye. 35, 1084–1101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01339-3 (2021).

Awad, R., Ghaith, A. A., Awad, K., Mamdouh Saad, M. & Elmassry, A. A. Fungal keratitis: diagnosis, management, and recent advances. Clin. Ophthalmol. 18, 85–106. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTJ.S447138 (2024).

Brown, L., Leck, A. K., Gichangi, M., Burton, M. J. & Denning, D. W. The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, e49–e57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30448-5 (2021).

Jaeger, E. E. et al. Rapid detection and identification of Candida, Aspergillus, and Fusarium species in ocular samples using nested PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 2902–2908. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.38.8.2902-2908.2000 (2000).

Cintra, M. E. C., da Silva Dantas, M., Al-Hatmi, A. M. S., Bastos, R. W. & Rossato, L. Fusarium Keratitis: A systematic review (1969 to 2023). Mycopathologia. 189, 74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-024-00874-x (2024).

Iyer, M. S. & Cousin, M. A. Immunological detection of Fusarium species in cornmeal. J. Food Prot. 66, 451–456. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028x-66.3.451 (2003).

Challa, S., Uppin, S. G., Uppin, M. S., Pamidimukkala, U. & Vemu, L. Diagnosis of filamentous fungi on tissue sections by immunohistochemistry using anti-aspergillus antibody. Med. Mycol. 53, 470–476. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myv004 (2015).

Kozel, T. R. & Wickes, B. Fungal diagnostics. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4, a019299. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a019299 (2014).

Raj, N. et al. Recent perspectives in the management of fungal keratitis. J. Fungi. 7, 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7110907 (2021).

Davies, G. E. & Thornton, C. R. A lateral-flow device for the rapid detection of Scedosporium species. Diagnostics. 14, 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14080847 (2024).

Tuft, S. et al. Bacterial keratitis: identifying the areas of clinical uncertainty. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 89, 101031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2021.101031 (2022).

Austin, A., Lietman, T. & Rose-Nussbaumer, J. Update on the management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 124, 1678–1689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.012 (2017).

Yoder, J. S. et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: the persistence of cases following a multistate outbreak. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 19, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.3109/09286586.2012.681336 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. The global epidemiology and clinical diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Infect. Public. Health. 16, 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2023.03.020 (2023).

Liu, X., Jiang, J., Yin, Y. & Ma, Z. Involvement of FgERG4 in ergosterol biosynthesis, vegetative differentiation and virulence in fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 14, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00829.x (2013).

Hu, Z. et al. Recent advances in ergosterol biosynthesis and regulation mechanisms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Indian J. Microbiol. 57, 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12088-017-0657-1 (2017).

Yang, C. et al. Study on the fungicidal mechanism of glabridin against Fusarium graminearum. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 179, 104963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2021.104963 (2021).

Kim, M. J. et al. Detection of Acanthamoeba spp. Using carboxylesterase antibody and its usage for diagnosing Acanthamoeba-keratitis. PLoS One. 17, e0262223. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262223 (2022).

Kim, M. J. et al. Detection of Acanthamoeba from Acanthamoeba keratitis mouse model using Acanthamoeba-specific antibodies. Microorganisms. 10, 1711, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10091711

Kim, M. J., Quan, F. S., Kong, H. H., Kim, J. H. & Moon, E. K. Specific detection of Acanthamoeba species using polyclonal peptide antibody targeting the periplasmic binding protein of A. castellanii. Korean J. Parasitol. 60, 143–147. https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2022.60.2.143 (2022).

Kim, M. et al. Evaluating the diagnostic potential of chorismate mutase Poly-Clonal peptide antibody for the Acanthamoeba keratitis in an animal model. Pathogens. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12040526 (2023).

You, I. C. et al. Clinical features and antibiotic susceptibility of Culture-proven infectious keratitis: a multicenter 10-year study. J. Korean Ophthalmol. Soc. 62, 447–462. https://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2021.62.4.447 (2021).

Ahearn, D. G. et al. Fusarium keratitis and contact lens wear: facts and speculations. Med. Mycol. 46, 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780801961352 (2008).

Ghenciu, L. A., Faur, A. C., Bolintineanu, S. L., Salavat, M. C. & Maghiari, A. L. Recent advances in diagnosis and treatment approaches in fungal keratitis: A narrative review. Microorganisms. 12 (161). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12010161 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. A chorismate mutase-targeted, core-shell nanoassembly-activated SERS immunoassay platform for rapid non-invasive detection of Acanthamoeba infection. Nano Today. 59, 102506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2024.102506 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Academic Research Support Project (2024) of the Korea Association of Health Promotion and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MIST) (RS-202400346635).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.K.M., H.H.K., F.S.Q. Experiment and data curation: H.J.J., M.J.K., H.A.L., Formal analysis: H.A.L., F.S.Q., H.H.K., E.K.M. Original draft: H.J.J., M.J.K. Writing-review and editing: H.J.J., M.J.K., H.A.L., F.S.Q., H.H.K., E.K.M. Supervision: E.K.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jo, HJ., Kim, MJ., Lee, HA. et al. Evaluation of the potential for diagnosis of fungal keratitis using a Fusarium-specific antibody. Sci Rep 15, 21583 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08719-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08719-3