Abstract

Agricultural residues are produced annually; recycling these wastes in various ways is considered economically valuable. In this context, biopolymer-reinforced composite materials were developed to create alternative, eco-friendly, and sustainable resources for different applications. With advancements in innovative chemical techniques, cellulose nanofibers with silica have been simultaneously obtained. Rice residues were transformed into silica-based cellulose nanofibers (SCNNP) through hydrolysis using ammonium persulfate (APS) under microwave radiation at 70 °C, 1.25 M APS, an irradiation time of 20 min, and a liquor ratio of 1:75. Additionally, rice residue was converted into silica nanostructure SiO2NP via hydrochloric acid hydrolysis followed by calcination at 600 °C. The principal characterizations of the extracted SCNNP and SiO2NP were evaluated using FTIR, XRD, BET surface area analysis, SEM, TEM, EDX and ζ-potential measurements. To produce cellulose/silica hybrid composites on a paper matrix, co-processing of the isolated SiO2NP and/or SCNNP, which contained silica, was considered. Different concentrations of [SiO2NP (0.25–3%w/v)/SCNNP (0.5%w/v)] nanocomposites were used to modify the fabricated paper sheets, with cationic polyacrylamide (CPAM) serving as a binder. Fabricated paper sheets treated with various concentrations of (CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP) nanocomposite solutions were prepared. The impact of SiO2NP and/or SCNNP on the modified paper’s surface structure, strength, barrier, and UV shielding characteristics was examined. To evaluate color properties, the fabricated paper sheets treated with different concentrations of CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP, were silk-screen printed using disperse dye. Under different conditions (temperatures of 170–210 °C and time of 30–60 s.), the printed paper sheets were tested as heat transfer paper in sublimation transfer printing of polyester fabrics. Polyester samples printed using sheets treated with CPAM/0.5% SCNNP and CPAM/3% SiO2NP showed enhanced color depth. All polyester samples printed with modified sheets demonstrated outstanding fastness properties. Additionally, some treated paper sheets showed remarkable transfer stability during a second printing run.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Regular exposure to light, particularly UV light, triggers photolysis and photooxidation reactions that degrade food quality. These processes accelerate food degradation by generating free radicals and reactive oxygen species, which impart unpleasant tastes and odors, reduce nutritional content, and cause discoloration1,2. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation, a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than visible light (100–400 nm), is categorized into three bands based on wavelength: UVC (200–280 nm), UVB (280–315 nm), and UVA (315–400 nm)3,4. UV exposure not only promotes food spoilage but also increases the risk of microbial contamination by pathogens like E. coli and L. monocytogenes, leading causes of foodborne illnesses5,6. Globally, over 550 million food-borne illnesses occur annually, primarily due to contaminated food consumption7,8. To address the environmental and health issues posed by non-biodegradable plastic packaging, researchers have turned to biopolymer-based UV protective films derived from natural materials such as (chitosan, cellulose, starch, gelatin, and alginate …etc.)9,10. These biopolymers are non-toxic nature, biocompatible, and biodegradable, making them sustainable alternatives to synthetic polymers11,12. Agricultural waste management is critical for sustainable resource use, given the 30 to 35 million tons of residue produced annually13,14. Traditionally, these wastes (e.g., sugarcane bagasse, wheat straw, rice husks, and corn stalks) were burned or composted, but recent efforts have focused on converting them into value-added products like nanocellulose (NC)15. A plentiful natural biopolymer, cellulose can be efficiently made into hydrogel and composite forms16,17. NC is renewable, non-toxic, and biodegradable, with exceptional mechanical properties, a large surface area, high crystallinity, and low density18. Ammonium persulfate (APS), an eco-friendly oxidant, enables efficient NC production via microwave-assisted synthesis—a rapid, single-step process19,20. However, NC’s poor UV-blocking and thermal stability limits its packaging applications. To overcome this, nanomaterials like SiO₂, ZnO, TiO₂, Cu NPs, CeO₂, carbon quantum dots (CQDs), and plant extracts are incorporated for enhanced UV protection1. While paper and paperboard are widely used in packaging, their low mechanical strength, high water vapor penetration, and poor barrier capabilities restrict their effectiveness. By incorporating nanoparticles (e.g., SiO2, ZnO, and TiO2)21,22 into paper matrix formulations, these materials gain improved gas barrier properties, UV resistance, and antimicrobial/antioxidant functionality, extending food shelf life,23,24,25.

Rice husk ash (RHA), a byproduct of combustion, is rich in silica (SiO2), a chemically, physically, and thermally stable, and cost-effective material26. With 760 million tons of rice husk waste and 1.14 billion tons of rice straw waste generated annually (containing 15–20% silica), extracting silica nanoparticles (SiO2NP) offers a sustainable solution27,28. Incorporating SiO2NP and/or silica-based cellulose nanofibers SCNNP into paper coatings improves tensile strength, water resistance, UV blocking, and food preservation29,30,31.

In transfer printing, once the printed paper and fabric come into direct contact within a press or calendar at an elevated temperature, specific nonionic dispersed dyes are transferred in the vapor phase from a thermoplastic polymer film to the interior of the fabric surface adjacent to the printed paper. This process occurs through two complementary stages: first, a pattern is printed on special transfer paper using an appropriate printing technique; second the pattern is heated, causing the dye vapor to diffuse from the paper into the fabric using a flat-bed press. The dye vapor then penetrates the fiber pores and becomes permanently embedded within the fibers32. Digital printing (including Inkjet, Transfer, and Laser) necessitates inks with outstanding fastness properties, and the printed paper should be subjected to per-finishing treatment to remain durable. The resolution of the printed image is controlled by the coating layer on the paper surface. Parameters involved surface area, pore structure, and SiO2NP additive mainly affect image properties. Applying a thin layer of SiO2NP coating to the paper surface can improve fastness by decreasing coating permeability, which in turn reduces printing ink dispersion on the paper surface and structure33,34,35.

Our study had several main objectives. First, we aimed to develop an efficient single-step chemical procedure, using microwave irradiation, to extract cellulose nanofibers (CN) from rice waste along with silica, resulting in a silica-based cellulose nanofibers (SCNNP) hybrid nanocomposite. The second step involves creating novel nanocomposites using locally accessible raw materials. To achieve this, pure SiO2NP was extracted from rice husk (RH) and combined with hydrophilic polymers, including SCNNP to enhance the properties of nanocellulose. We investigated the potential advancement of paper uses and applications by improving the chemo-physical characteristics of these hybrid organic/inorganic nanocomposites and leveraging renewable resource-based technologies. Third, to obtain multifunctional applications in packaging and printing, SiO2NP and/or SCNNP were utilized as coating materials to enrich the surface of paper sheets, and their mechanical, barrier, and UV radiation shielding properties were then evaluated. Fourth, the sublimation transfer printability of treated paper sheets was examined in the printing of synthetic fabrics (polyester) under various conditions (temperatures and times), and fastness measurements (color strengths K/S, washing, light, and perspiration) were assessed using standard methods.

Experimental

Materials

The unbleached pulp made from rice residue was purchased by the Rakta Company for pulp and paper in Egypt. The chemical composition of rice agro-waste pulp was checked according to the Tappi standard method, including silica at 13% (T 245 om-94), lignin at 14% (T 222 om-88), ash at 15% (T 211), pentosane at 15% (T 223 cm-84), and α-cellulose at 55% (T 203 cm-99). We purchased ammonium persulfate (APS) from Sigma-Aldrich. Every test was run in triplicate, and the data’s mean value was emphasized.

Extraction of SCNNP and SiO2NP nanoparticles

Silica-based cellulose nanocrystalline (SCNNP) isolation with microwave support

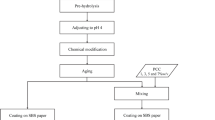

In the strategy to prepare SCNNP from rice residue, the following parameters were used: temperature (70 °C), concentration (1.25 M of APS), irradiation time (20 min), and liquor ratio (1:75). The reaction mixture for one gram of rice waste fiber was sterilized in a completely hermetic microwave reactor coupled to a perpetually cooling system. Dialyzing the resulting suspensions against distilled water for four to seven days was necessary to reduce the solution conductivity to approximately 5 μscm−1 (pH 4). The yield of the prepared SCNNP was calculated as (27.93 ± 0.55%), which was determined by subdividing the weight of the final lyophilized product by the original weight of the starting material. The schematic diagram of the modified microwave reactor system used to extract SCNNP is presented in Fig. 1a.

Pure silica nanostructure separation from rice husk

RHA with a high silica concentration was produced when the rice husk RH was ignited. RH was utilized as a cost-effective and abundant source of biogenic silica nanoparticles for obtaining pure SiO2NP with regulated phase, purity, and shape. This was accomplished by calcining RH in an oven muffle at 600 °C after pre-treating it with hydrochloric acid (1 M HCl). Subsequently, SCNNP were separated from RHA as sodium silicate using sodium hydroxide (2 M NaOH). The silicate solution was then titrated with hydrochloric acid (2 M HCl) until the pH reached 7.

The following is the proposed mechanism for alkali/acid reaction: To extract silica, RHA was first dissolved in sodium hydroxide and then converted into sodium silicate according to Eq. (1). The second step is the precipitation using hydrochloric acid, as shown in Eq. (2):

The establishment of a prolonged 3D Si–O–Si network results from the alkaline treatment, followed by hydrochloric acid solubilization of the supported silanol (R3Si–OH) groups and subsequent condensation28.

Preparation of paper sheet

The paper sheet was prepared from bagasse agro-waste. The fibers underwent two chemical processes, lignin removal and cellulose isolation. Using the S.C.A. sheet old model (AB Worentzen and Wettre), the paper sheet was made in accordance with the S.C.A. standard. Within the apparatus, a sheet with a diameter of 165 mm and a surface area of 214 cm2 was created. Approximately 1.8 g of oven-dried pulp was used for each sheet. After formation, a hydraulic press was used to press the sheet for four minutes, and it was dried with the aid of a rotating drum.

Fabrication of SiO2NP /SCNNP nanocomposite on paper sheets

The SiO2NP/SCNNP nanocomposite was used to coat the prepared sheets, and cationic polyacrylamide (0.2% w/v CPAM) was used as a binder. To ensure the homogeneity of the solutions, the mixtures were stirred with a homogenizer for 3 min, followed by sonication for 15 min. The fabricated paper sheets were then treated with varying concentrations of the (CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP) nanocomposite solutions using a coating applicator, as indicated in Table 1. The final coating thickness was approximately 120 μm. Subsequently, the paper sheets were hard-pressed between two sheets of filter paper and then dried on a cylindrical drum at 105 °C for two hours. Prior to examination, the treated paper samples were conditioned at 50% relative humidity and 23 °C for 24 h.

Characterization and chemical composition of SiO2NP, SCNNP, and modified paper sheets

The following measurements were used to characterize the extracted SCNNP, SiO2NP, and modified paper sheet chemically and morphologically:

FTIR Spectroscopy: The FTIR spectra of the variously produced samples were recorded using FTIR spectroscopy (JASCO FTIR 6100 spectrometer, Tokyo, Japan) in the 4000–400 cm-1 region, with 60 scans and a resolution of 4 cm-1.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): An X-ray diffractometer (Siemen D5000) with a CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) running at 30 nA and 40 kV was monitored to perform an XRD examination. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): The high-resolution JEOL-JEM 2100 (Tokyo, Japan) was used to conduct TEM examination.

Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDAX) and Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy (ESEM): A Quanta FEG-250 microscope (Waltham, MA, USA) was used to perform EDAX and ESEM on customized paper sheets at a voltage of 20 kV.

Particle Size and Porosity of SiO₂NP: the average particle size and porosity structure of SiO2NP were determined using the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm and the Quanta Chrome Touch Win device.

Surface Area Estimation: The density functional theory (DFT), Langmuir technique, and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) methods were employed to estimate the average surface area using a particle sizing system (Santa Barbara Inc., California, USA).

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Derivative Thermogravimetry (DTG): The TG and DTG curves for coated paper sheets were investigated using a PerkinElmer AC7/DX TGA7 thermal analysis controller. The tests are conducted in a dynamic nitrogen environment (20 ml/min) with a heating rate of 10 °C/min in a temperature range of 20–600 °C using platinum crucibles.

Ultraviolet Protection Factor (UPF) Estimation: The UPF was estimated using a UV-Shimadzu 3101-PC-Spectrophotometer in accordance with the Australian/New Zealand Standard (AS/NZS-4399-1996).

Strength and barrier characteristics of paper sheet

A universal testing machine (LR10K; Lloyd Instruments, Fareham, UK) was utilized to measure tensile strength by applying a 100-N load cell at a constant crosshead speed of 2.5 cm/min in accordance with TAPPI standard procedure (T494-06). ASTM E96-E80 was followed while determining water vapor permeability (WVP). Five grams of anhydrous calcium chloride were placed in aluminum cups, which were conditioned for 24 h at 25 °C and 50% relative humidity before being hermetically covered with coated paper sheets. The coated side faced the humidified side, and The WVP was established using the following formula:

where x is the film thickness, A is the permeation area, (W/t) is the slope of the weight loss over time, and ΔP is the partial water vapor pressure difference between the atmosphere in the cup and the saturated sodium chloride solution, corresponding to 0–75% relative humidity (i.e., 2.385 kPa).

The ASTM D722-93 procedure was used to determine oil resistance. Five grams of sand with a specific particle size and a piece of white book paper were placed on top of the treated paper samples. The sand was saturated with a specified quantity of oil that had been combined with soluble red dye. Following that, the treated paper sheet test area was subjected to conditions of 50% relative humidity and 25 °C. The time required for oil penetration, observed as the red staining of white book paper through the modified paper samples, was recorded to the nearest ten seconds. For each measurement, the mean value of three estimations was determined, and the standard deviations (STDEV) were calculated.

Printing process and color strength measurements

The 150 g/m2 polyester fabric (provided by a private Egyptian company) was treated with 0.5 g/l anionic detergent and 1 g/L sodium carbonate for one hour at 70 °C, then allowed to air dry at room temperature. The thickening agent Bercolin CPK was provided by Berssa-Turkey, the dispersed dye Disperse Red 60 (200% LS) Fig. 1b was provided by Zhejiang Runtu Co., Ltd, and the 60-gm transfer paper was provided by Protucal Soporcel Company.

Printing paste and printing technique

Here is the recipe for the paste listed in order: 2:4:94 water, synthetic thickener, and dispersed dye. The treated and commercial papers are printed using the prior recipe and then air-dried using a silk screen process. Additionally, the previously printed paper is used to print the polyester fabric via a heat transfer technique. A hydraulic heat press machine (40 × 60 cm) was used for the transfer. The temperatures and timeframes tested for the transfers were 170, 190, and 210 °C, and 30 and 60 s, respectively. The printed samples were allowed to cool at room temperature before the paper is removed.

Color strength (K/S) and CIELAB color parameters.

The Hunter Lab (Ultra scan-PRO D65, USA) evaluates the color strength and CIELAB color parameters (L*, a*, and b*) of the prints at λmax 680 (nm). The Kubelka–Munk relationship was used to quantify the color strengths (K/S) of printed samples.

where S is the scattering coefficient, K is the absorbance coefficient, and R is the reflectance36. The sample’s brightness is indicated by L*, and its red-green and yellow-blue shifts are shown by a* and b*. The fastness properties to washing, perspiration, and light were evaluated using the standard procedures outlined in the AATCC Technical Manual, Test Methods 8 (1989) 68, 23 (1993); 15 (1989) 68, (1993) 30 and (16-2004), respectively.

Results and discussion

Microwave treatment mechanism

The interaction was based on the scientific theory that microwave radiation has high selectivity, and this selectivity depends on the dipole moment of the materials exposed to it. Furthermore, numerous investigations have demonstrated that microwave irradiation superior to conventional heating in terms of enhancing the efficacy of persulfate ions in APS compounds. Thermal and non-thermal effects, rapid and even heating, and polar coupling are the reasons for the high rate of sulphate radical production when combining microwave and APS processes. Water is the perfect solvent for processes aided by microwaves because of its high polarity and the great efficiency of persulfate ions when exposed to microwave radiation. The fundamental concept for producing high-quality SCNNP is the proper ratio of salt to water, temperature, and energy20. Hydrogen peroxide molecules and sulphur tetraoxide free radicals were produced when the APS aqueous solution was exposed to microwave radiation. These hydrogen peroxide molecules and sulphur tetraoxide free radicals have the ability to hydrolyze cellulose’s amorphous portions and open the aromatic rings of lignin, producing SCNNP37.

Silica-based cellulose nanocrystals (SCNNP) and silica nanoparticles (SiO2NP) characterization

FTIR analysis

As seen in Fig. 2a, FTIR analysis was applied to trace the molecular structure of the raw RH, produced SCNNP, and SiO2NP employed in this investigation. Numerous distinctive absorption peaks were visible in the raw RH spectra, indicating the presence of inorganic materials, such as SiO2NP, and organic materials, including cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. The broad peak in the RH spectrum at approximately 3407 cm-1 represents the O-H stretching vibrations. In the structure of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the C–H aliphatic bonds in the –CH3 and CH2 groups can be linked to the absorption peak at 2914 cm-1. The vibration bands at 1460, 1424, and 1370 cm-1 are attributed to the C-H stretching vibrations of the CH2 groups. In addition to the vibration brought on by adsorbed water molecules, the peak at 1647 cm-1 is attributed to the stretching vibrations of the -C=O groups in aldehydes and ketones, whereas the peak at 1515 cm-1 is attributed to the stretched -C-O groups in carboxylates. The peak at 1159 cm-1 represents the C-O stretching of the aliphatic ether. Furthermore, the stretching vibrations of the Si-O-Si groups’38 manifest as broad peaks at 1083, 789, 523, and 465 cm-1.

For cellulose nanocrystals made utilizing the microwave irradiation method (SCNNP), FTIR not only shows the entry of new bands but also changes in the intensities and locations of the key cellulose fingerprint peaks (Fig. 2a). The peak from 2900 cm-1 to 2850 cm-1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of the methyl groups, whereas the broad band in the area around 3314 cm-1 is ascribed to the intra and inter-hydrogen bonded O–H stretching vibrations. The deformation vibration of adsorbed water molecules was represented by the bands at approximately 1630 cm-1. The glycosidic ring vibrations of C–O–C, C=O, C–H, and O–H are responsible for the distinctive cellulose fingerprint bands, which are found in the 1500–800 cm-1 spectral range39. A corresponding curve for the carboxyl group appeared at 1705 cm-1 and 1750 cm-1 peaks for SCNNP, which could be interpreted as the -C=O valence vibration of -COOH groups through the interaction of cellulose fibers with free radicals created during the chemical treatment under microwave irradiation37. The carbonyl groups in aldehydes and ketones’ –C=O stretching vibrations were identified as the cause of the peak at 1648 cm-1. Furthermore, we may infer from the increase in peak intensity at 1032 cm-1, which corresponds to the stretching of the pyranose ring from -C-O-C- that cellulose content and crystallinity rise while the pyranose ring stays intact with APS treatment. Additionally, the decrease in the band’s intensity at 900 cm-1 due to asymmetric out-of-plane ring stretching in cellulose caused by the β-linkage, which represents the amorphous portion of the cellulose fibers, shows that the microwave-prepared SCNNP retains a high degree of crystallinity40,41. Two distinctive vibrational peaks for Si-O-Si also emerged at wavenumbers ≈ 797 cm-1 and 464 cm-1. Furthermore, using microwave radiation, the extent of oxidation was calculated by analyzing the infrared spectra of the generated SCNNP samples, which reached 0.076. The degree of oxidation concerning the cellulose backbone structure can be determined by26 comparing the intensity of the carboxylate peak at 1750 cm-1 to that of the strong band near 1060 cm-1.

The FTIR spectrum of the SiO2NP silica gel, shown in Fig. 2a, showed vibrational bands characteristic of amorphous silica and adsorbed water molecules at approximately 464, 967, 784, 1096, 1543, 1642, 2930, and 3461 cm-1. The bending and stretching vibrational bands of the adsorbed water molecules appeared around 1642 and 3461 cm-1, respectively, consistent with the previously reported findings42,43. The peaks at 1096, 967, 784, and 464 cm-1 were attributed to the siloxane group stretching vibrations within the synthesized SiO2NP. Specifically, the vibrational absorption at about 1096 cm-1 corresponded to the siloxane (Si-O-Si) linkages of the silicate network. Furthermore, symmetric and asymmetric vibrational bands of the Si-O-Si bonds were observed around 784 and 967 cm-1, respectively. The broad vibrational band at 3461 cm-1 was due to the O-H stretched vibration of the silanol groups (Si-OH) present in the silica gel nanoparticles. These findings are consistent with the published data and corporate to the amorphous chemical structure of SiO2NP's44.

X-ray diffraction

XRD analysis of RH was performed to determine whether the investigated materials were amorphous or crystalline. Figure 2b shows the main diffraction peaks for RH at Bragg angles (2θ) of 15.5° and 22.33°, which are attributed to the diffraction patterns from the crystalline structure of its cellulose content. A peak equivalent to silica, appeared at Bragg 2θ angles at 44.48°.

The impact of the microwave irradiation approach on APS hydrolysis and the crystalline structure of cellulose were demonstrated by the XRD profiles of SCNNP fibers (Fig. 2b). The crystalline form of cellulose I exhibited four lattice peaks at 2θ = 14.86 (\(\overline{110}\)), 16.08 (110), 22.58 (200), and 34.18 (004). Upon separation of the silica-based cellulose nanocrystals (SCNNP), a peak corresponding to silica observed at a Bragg 2θ angle of 44.48 (212). Additionally, the amorphous portions of the cellulose fibers, as well as the non-cellulosic materials (lignin, hemicellulose, and extractives) were eliminated. The crystalline regions underwent rearranged into a more ordered structure, resulting in a crystalline index of 66.2% for the SCNNP sample produced using microwave radiation. This outcome attests to the effectiveness of the developing procedure utilizing the suggested approach13,45.

XRD profiles for a sample of SiO2NP derived from gray RHA at 600 °C are displayed in Fig. 2d. These profiles suggest that burning the hulls at 600 °C resulted in the formation of an amorphous biogenic SiO2NP structure. The primary peaks of SiO2NP were observed at Bragg 2θ angles of 22.18° and 44.39°, corresponding to the (101) and (212) planes, respectively46. The broadness of the XRD peaks of the extracted SiO2NP indicates that the synthesized biogenic silica nanoparticles were amorphous and nanoscale in dimension. Furthermore, the acid treatment altered the chemical composition of the silica nanoparticles. The sharpness and high intensity of peak at Bragg 2θ 44.39 for SiO2NP, following the HCl acid treatment process, indicates the high purity of extracted silica due to the removal of oxide impurities. It is known that the calcination temperature influences the type of silica produced with crystalline forms typically developed above 700–900 °C47.

Morphological study

The microstructure of the external surface of RH and SiO2NP was observed using SEM, as shown in Fig. 2c, d. The surface morphology of RH revealed well-arranged micro-bumps across its surface. The RH outer epidermis exhibited an uneven and highly ridged structure with protrusions Fig. 2c48. SEM analysis (Fig. 2d) showed the amorphous structure of silica nanoparticles resulting from their nanoscale surface roughness49.

Transmission electron microscope TEM examinations Fig. 2e, f were performed to view the morphological features of the extracted SCNNP fibers that were produced via the microwave radiation approach and the isolated SiO2NP nanoparticles which calcined at 600 °C after treatment with HCl. The TEM images demonstrated the needle-like shape of the prepared cellulose nanocrystals, as well as the high homogeneity of their width, which ranged from 3 to 5 nm. The TEM images of the silica nanoparticles showed that the SiO2NP nanoparticles were spherical, with a regular and homogeneous morphology and a diameter ranging from 6.65 to 7.68 nm; they were also somewhat agglomerated.

EDX was performed to compare the elemental composition of RH, SCNNP produced by APS with microwave irradiation and SiO2NP, as shown in Fig. 2g, h, and i. The EDX results indicated a high proportion of silicon in the SiO2NP and SCNNP samples, reaching 44.34 and 19.87 wt %, respectively. In contrast, the RH fibers used to extract the SCNNP contained only 5.67 wt % silicon. This highlights the effectiveness of APS in preserving the silica content during the isolation of SCNNP under microwave irradiation. Furthermore, the isolated silica, primarily composed of silicon and oxygen, exhibits great purity of SiO2NP.

Bet surface area

The pore size and specific surface area were determined using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. The textural and structural properties, including BET surface area (394 m2/g), average pore radius (7.71 nm), mean diameter (281.9 nm), and total pore volume (1.52 cc/g) demonstrate that the prepared silica possessed a high BET surface area. According to type IV isothermal adsorption–desorption curves with an H1-type hysteresis loop shown in Fig. 2j, the SiO2NP product was primarily mesoporous50.

Characterization of modified paper sheets

FTIR evaluation

Paper sheets’ cellulosic fibers and the CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP nanocomposite were examined chemically and physically using FTIR Fig. 3. The representative absorption peaks of cellulose were visible in the unaltered paper’s FTIR spectra. A peak at 1648 cm-1 also indicated the presence of interstitial or adsorbed water in the cellulose structure. The C-H stretching vibration was represented by absorption in the 3000–2800 cm-1 range, whereas the asymmetric and symmetrical deformation of the CH2 and C-H groups caused absorption in the 1450–1350 cm-1 range. Ultimately, the fingerprint of cellulose was represented by the complex and intensive absorption in the 1300–900 cm-1 range, mainly related to the stretching mode of the C–O–C (1050–1060 cm-1) and C–O (1028 cm-1) bonds in the cellulose framework. The positions of these bands were influenced by intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding; hence they were strongly associated with modifications in the chemical surface groups15. General alterations in the absorption peaks in the corresponding FTIR spectra were noted upon incorporating the CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP nanocomposite into the paper sheet. The broad band at 1642 cm-1 for the CPAM-modified paper sheets in Fig. 3b denotes the C=O stretching vibration in the -CONH2 bonds. Broad band at 3335 cm-1 represented the -OH stretching vibration in cellulose and the -NH2 stretching vibration of the amide group in CPAM. Peaks at around 1158 cm-1 were attributed to -CO in -COOH. The characteristic band at 1137 cm-1 in Fig. 3c, d, and e for paper sheets treated with nanoparticles (SiO2NP and/or SCNNP) represented the formation of Si-O-Si. When paper sheets were treated with SiO2NP, the peak intensities at 798 and 458 cm-1, which are related to the SiO4 tetrahedron and O-Si-O deformation, respectively, became more noticeable. The characteristic bands at 1648 and 3335 cm-1 represented the -OH group on the surface of SiO2. Furthermore, a -CH3 bending vibration contributed to an absorption peak at 1429 cm-1 on paper sheets treated with SCNNP. Additionally, the lower intensity of the band at 900 cm-1, which represents the amorphous portion of the cellulose fibers, indicates that the microwave-prepared SCNNP presents a high degree of crystallinity in modified paper sheets, confirming that SiO2NP and/or SCNNP are successfully modified the paper sheets51.

Paper’s surface morphology

The surface morphology changes of both uncovered and covered paper sheets treated with various blended nanocomposites (CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP) were illustrated in Fig. 4. The deposition of CPAM, CPAM/SCNNP, CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP, and CPAM/SiO2NP significantly impacted the surface chemistry and network of cellulosic fibers. SEM analysis of the modified paper sheets revealed that CPAM formed a lamellar structure, enhancing the surface properties of the paper sheets. Additionally, the coating improved fiber dispersion within the paper matrix and the chemical compatibility of the coated nanoparticles by promoting better adhesion and bonding to the fiber surfaces. As observed, the fibers were more uniformly distributed in the coated paper sheets compared to the uncoated ones, which exhibited a random distribution. Paper sheets treated with CPAM/SiO2NP appeared more homogeneous than those modified with CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP. The coating materials are chemically cross-linked with the cellulose fibers and were distributed both on the surface and within the fibers. Moreover, the nanoparticles tended to aggregate within the fiber-based matrices when the CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP nanocomposite was used to treat the paper sheets24. EDAX analysis Fig. 5a–e was used to detect the elements on the modified paper surfaces. As shown in Fig. 5d, silica exhibited a prominent peak, indicating a higher proportion of silica in paper sheets covered with CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP.

Thermogravimetric analysis

TGA and DTA are effective systems for examining the thermal degradation behavior of specific materials and quantifying their mass loss. Assessing how coated fillers affect a paper’s ability to maintain thermal stability under high temperatures during transfer processes and ultraviolet radiation is crucial. The decomposition curves and thermal decomposition parameters for unmodified paper sheets (S0) and those modified with CPAM (S1), CPAM/SCNNP (S2), CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP (S6), and CPAM/SiO2NP (S10) mixtures, are generally displayed in Fig. 6 and Table 2. The figure clearly illustrates a three-step breakdown process, consistent with previous findings. These three phases were identified as: drying (40–150 °C), organic volatile matter elimination (215–350 °C), and carbonaceous char combustion (350–690 °C)32.

According to the TG curves for our modified samples, three phases of mass loss occurred between 35 and 602 °C for the S0, S1, S2, S6, and S10 paper matrices. The primary decomposition stage, attributed to absorbed water evaporation, took place at (35–146, 37–142, 35–123, 37–141, and 36–153 °C), resulting in weight loss of (5.03, 4.10, 2.08, 4.02, and 3.30%), respectively. The secondary stage occurred at (254, 252, 193, 235, and 235 °C), resulting in weight loss of (73, 68.14, 60.18, 54.27, and 49.86%), respectively. The third stage, producing maximum weight loss of (99.60, 87.27, 85.22, 71.66, and 64.67%), was achieved at approximately (389, 397, 405, 397, and 391°C), reaching completion at (602, 601, 609, and 602 °C) for S0, S1, S2, S6, and S10, respectively.

As demonstrated in Table 2, unloaded bagasse paper (S0) demonstrated lower thermal stability and a reduced capability for char formation compared to the other tested paper samples. Cellulose degradation typically proceeds via a depolymerization mechanism of glycosyl units, producing high-boiling products such as levoglucosan. At higher temperatures, levoglucosan can further decompose into lighter, combustible gases. Moreover, the inclusion of metals, pigments, fillers, or additives can significantly alter the degradation pathway, decomposition products, and thermal stability52. Consistent with previous results, all modified samples in this study showed a greater percentage of char production and enhanced thermal stability compared to the unloaded paper sheets. The analysis further indicates a significant relationship between the degradation temperature and the incorporation of SiO2NP and SCNNP. From Table 2, at approximately 390 °C, S10 showed the highest char yield production (41.49% opposed to 10.67% of control bagasse). Moreover, the residual char at 600 °C (RC600 °C) was 0.40% for unloaded paper S0, 12.73% and 14.78% for S1 and S2, respectively. While it was 28.34% and 35.33% for S6 and S10, respectively. The higher char values observed for S6 and S10 demonstrate improved thermal stability, which correlates with the presence of silica and silica-based nanocellulose nanoparticles. These improved results are attributed to the ability of the added fillers to stabilize the bagasse paper sheets structure and shift the thermal degradation process toward less volatile and non-flammable products. Furthermore, the dehydration breakdown mechanism of bagasse paper was restricted by the presence of these fillers, thus minimizing the depolymerization of cellulose to levoglucosan and promoting the formation of carbonaceous char (CO2, CO, H2O, and solid char)53.

The DTG curves revealed two stages of thermal degradation for both untreated paper sheets and those treated with CPAM, CPAM/SCNNP, CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP, and CPAM/SiO2NP. The first decomposition peaks for S0, S1, S2, S6, and S10, occurred at 93, 91, 81, 87, and 90 °C, respectively. The second DTG decomposition temperatures for the modified and unmodified paper sheets were 350, 353, 313, 346, and 350 °C, respectively. The findings indicated that the addition of fillers improved the thermal stability and stabilization of the bagasse structure. Based on the thermogravimetric data, the modified papers could be employed for UV protection in packaging applications and as multifunctional heat transfer printing papers for polyester sublimation printing.

Strength properties of paper sheets coated with (CPAM/ SiO2NP and/or SCNNP)

The relationship between paper thickness and grammage is represented by the bulk density of paper sheets. Higher bulk-density papers are typically opaque, light, airy, and thick. As anticipated, the application of (CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP) loading enhanced the bulk density of the modified paper sheets (Table 3). The attachment of (CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP) nanocomposites favorably impacted the mechanical strength properties of the modified paper sheets, resulting in a notable increase in maximum load, tensile index, and breaking length. Measurements of paper sheets’ tensile strength provide specific information about their resistance to breaking under stress; this breaking strength is controlled by the cellulosic fibers’ strength, length, surface area, and consequently their bonding strength. Regarding the tensile index, a gauge of a paper’s intrinsic strength, it increased to 0.27 and 0.29 KN.m/g, when paper sheets modified with 0.5% SCNNP mixed with 0.5% or 1% SiO2NP nanocomposite, S5, and S6, respectively, were used. Furthermore, adding CPAM/SiO2NP improved the observed tensile index, reaching its maximum (0.33 KN.m/g) for the modified paper sheet S9, which contained 1% SiO2NP. Table 3 clearly showed that the observed improvement percentage in the measured breaking length, approximately 35, 38, and 56% for S5, S6, and S9, respectively, was caused by the presence of the (CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP) nanocomposite. According to the experimental results, paper sheets treated with SiO2NP/ SCNNP often demonstrated better mechanical performance than untreated ones. CPAM is a positively charged polyelectrolyte with a high molecular weight (≈ 1.106). When the CPAM/SiO2NP suspension was blended with nanocellulose fiber suspension, the CPAM-covered SiO2NP and their assemblies were electrostatically attracted to the cellulose fibers, causing the nanocomposite to adsorb and be retained within the cellulose matrix of the paper. This explains the strong performance of modified paper sheets. The cellulose interface adsorption will prevent SiO2NP assemblies from moving and help maintain the order and assembly structure of the nanoparticles23. Additionally, the surface of SiO2NP’s has numerous hydroxyl groups that can form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups in the cellulose matrix, increasing cellulosic fiber adhesion and, consequently, fiber-to-fiber bonding54. The schematic mechanism of CPAM with SiO2NP and SCNNP is represented in Fig. 7.

Barrier properties of paper sheets coated with (CPAM/ SiO2NP and/or SCNNP)

Water vapor permeability

Other measurements were performed for the modified paper’s water vapor permeability (WVP) and compared to those of the unmodified material. Coated paper sheets were examined for WVP, which was measured as the amount of water vapor that permeates a paper matrix per unit area and time under specific circumstances. As shown in Table 4, the treatment of paper sheets with SiO2NP and/or SCNNP induced a reduction in WVP, compared with the control sample.

The results demonstrated that the modified paper sheets exhibited decreased hydrophilic properties, which limited the amount of water that could pass through the paper network. The blending of CPAM with SiO2NP and/or SCNNP likely resulted in the formation of a homogenous network on the paper sheets, which significantly reduces the voids in the paper matrix, producing a strong and rough surface and improving water vapor resistance. This reduction in porosity of the fiber matrix could explain the observed decrease in WVP and was confirmed by SEM characterization52. In addition to mechanical strength, low WVP is a necessary characteristic for food packaging to preserve the contents for an extended time.

Oil resistance

As shown in Table 4, coated paper sheets showed superior oil resistance (660–1800 + s) compared to the control paper sheets (300 s). Specifically, the S5 (CPAM/1%SiO2NP/0.5%SCNNP), S6 (CPAM/3%SiO2NP/0.5%SCNNP), S8 (CPAM/0.5%SiO2NP), and S10 (CPAM/3%SiO2NP) coated sheets demonstrated oil resistance of approximately 1800s, which meets the requirements for printing applications. The initially large pore size in the paper indicates a relative lack of pores in the paper matrix, contributing to the development of oil resistance. This compact structure can prevent oil from penetrating through capillaries; conversely, larger pore diameters facilitate oil flow through the paper matrix’s network. The presence of SiO2NP in rice husk-derived silica nanoparticles and silica-based nanocellulose increases the tortuosity of the network for oil molecules, slowing their migration and penetration through the paper surface and helping fill the gaps between the cellulosic fibers. SEM reveals the aggregation of SiO2NP and SCNNP on the surface, further preventing oil from reaching the substrate. This strategy shows promise for printing applications requiring superior barrier features24.

UPF measurements for modified paper sheets

Ultraviolet Protection Factor (UPF) values are categorized as poor (below 20), acceptable (between 20 and 29), very good (between 30 and 40), and excellent (beyond 40), as seen in Table 5. The findings indicated that while modified paper sheets possess high UV protection properties due to alterations in the paper sheet matrix, untreated paper sheets exhibited low UV protection. Additionally, utilizing (CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP) nanocomposites enhanced the UV protection of paper sheets to the maximum levels, with CPAM/SiO2NP S10-coated paper sheets showed remarkable improvements in protection values (96.20 UPF rating and blocked 98% of UV radiation) Fig. 8. This improvement was likely caused by potential crosslinking between cellulose fibers in paper sheets and (CPAM, SCNNP, and SiO2NP) via surface hydroxyl groups, as demonstrated by previous investigations28,55. Both photochemical reactions and free radicals can oxidize lipids, break down proteins, destroy antioxidants, alter color and substance, and create unwanted flavorings and odors. Therefore, the group has a lone pair of electrons or π bonds that can absorb the UV wavelengths, which include the UV and visible light ranges from 200 to 800 nm. Several biopolymer-based films, such as cellulose, lignin, gelatine, and chitosan, can also absorb substantial quantities of UV radiation, depending on their structural arrangements and composition. These biopolymers frequently include functional groups like carbonyl, hydroxyl, amino, and aromatic groups that have UV screening properties. The effectiveness of a biopolymer film’s UV screening can be increased by raising the concentrations of specific functional groups in the film56. Exceptional UV light absorption has been recorded for various kinds of metal oxides, including ZnO, TiO2, and CeO2. Incorporating TiO2 NPs into CMC/guanidinylated chitosan films, for example, has been shown to block 98% of UV light57,58. The treated samples exhibited lower transmittance % for both UVA and UVB radiation when compared to the blank sample, as shown in Table 6. The paper sheet treated with CPAM/SiO2NP (S10) exhibited the lowest transmittance rate 3.4 and 0.8 for UVA and UVB radiation, respectively compared to S0 sample. Xia, Zhou, et al. (2021) demonstrated an improvement in UV shielding characteristics for a cellulose matrix made from wasted corrugated boxes. The results revealed that the cellulose-based sheets produced by water and ethanol treatment recorded transmittance percentages of 34.68 and 33.42 for UVA and 13.9 and 14.14 for UVB, respectively, compared to the blank of 86.08 and 79.7759. Ahmed, Adak, et al. (2019) fabricated lyocell-based nanocellulose NC/graphene oxide GO nanocomposite film sheets. The quantified UVA and UVB transmittance % for NC/GO film were 76.75% and 63.66%, respectively, indicating that, it has a low UV protection ability in both UVA and UVB radiation zones60. The carboxyl, hydroxyl, and carbonyl functional groups in SCNNP and SiO2NP nanoparticles are essential to their UV-shielding capabilities and are known to enhance their efficacy61,62. Generally, CPAM/SiO2NP-coated paper sheets exhibited higher UV resistance than other samples. Figure 7 displays a graphic representation of a paper sheet coated with a CPAM/SiO2NP/SCNNP nanocomposite for UV protection. In our study, the functionalized CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP nanocomposite was applied not only as a transfer paper used in textile printing applications but also as a multifunctional coated paper sheet for UV protection in the packaging fields.

Color properties of printed paper

Since cellulose paper has no affinity for dispersed dyes, it is the primary choice as a carrier for these dyes in sublimation transfer printing. To avoid a mottled effect caused by varying thermal insulation of the paper when in contact with the heating element and non-homogeneous paste adsorbents, a high-quality with a uniform-structure is a basic requirement for an accurate and high-design transfer from the applied printed paper. This paper must be capable of releasing non-absorbed dye and also be strong enough to withstand the action of heat and pressure63,64.

The percentage of paste uptake on different treated sheets is shown in Table 7. As the concentration of silica nanoparticles in the treatment process increases, the dye uptake percentage decreases. The presence of SiO2NP helps fill the gaps in paper structure. This allows the water content of the printing paste penetrates the inner layer, keeping dye paste adhered to the surface. Furthermore, the SiO2NP imparts the required level of hydrophobicity to control dye paste adsorption and avoid a greater tendency to absorb water, resulting in poor printing properties. Table 7 also showed the color properties of printed paper sheets using disperse dye paste, indicating that all the treated paper samples had improved or comparable color properties to that of commercial transfer paper (lower L value indicates darker color shade)32,34,65.

Furthermore, the microscopic surface profile, as revealed by SEM images, showed that the printed paper treated with CPAM/0.5% SiO2NP (S8) and CPAM/3% SiO2NP (S10) displayed a more homogeneous and uniform surface, featuring fewer gaps and surface imperfections when compared to commercial or untreated paper sheets. Additionally, the upper layer containing dye paste appeared smoother, enhancing the prints’ consistency and clarity, as illustrated in Fig. 963. Consequently, S8 and S10 paper sheets are expected to exhibit improved color transfer production when utilized as transfer paper for sublimation polyester printing, as demonstrated in the next section.

Color depth and fastness properties of polyester fabric printed by treated paper via sublimation transfer technique

The color depth represents the actual dye content on the printed fabric, i.e. K/S. Table 8 shows that the K/S and CIE lab color parameters for polyester fabrics printed using the sublimation heat transfer technique with both former-treated and commercial paper sheets. The results indicate that the type of treatment, as well as the time and temperature of the transfer process, are the key factors in controlling the color depth and the quality of dye preserved by the fabrics. Increasing the transfer temperature and/or time, resulted in more dye transfer, consequently increasing the color strength (K/S value) of the printed fabrics due to the increased vapor pressure of the applied dye. Furthermore, to improve the dye affinity for the fiber and prevent dye retention on the paper surface32,66, the affinity of the dye vapor for the paper filter, coating, treatment, and printing paste thickener should be minimized. Consequently, the best color yield improvements were obtained at 210 °C for 60 s, which were established as the optimum conditions, as shown in Table 8 and Fig. 10.

The effect of paper treatment on the ease of dye release and color reproduction during polyester transfer printing was investigated. It was noticed that all treated paper samples exhibited improved dye release ability with sheets treated with S8 (CPAM/0.5% SiO2NP) and S10 (CPAM/3%SiO2NP). This could be attributed to the silica nanoparticles’ paper treatment, which facilitates the release of the highest percentages of dye from their surface. As mentioned previously, SiO2NP nanoparticles fill the gaps in the fiber matrix, reducing the diffusion of the printing paste to inner layer and localizing dye particles on the paper surface. This localization helps achieve the best possible color density on the prints, reducing dye waste and increasing paper efficacy. This observation also aligns with the reported results of paper dye uptake67. Regarding the fastness properties illustrated in Table 9, all printed fabrics exhibited excellent fastness.

Additional constructive outcomes have been obtained from the reutilization of modified printed paper (under optimal conditions) for an additional printing run to evaluate the efficiency (durability) of the treated paper sheets for multiple transfer processes, aiming to reduce costs and preserve the environment. Table 10 displays the color strength and color parameters of polyester fabric printed by heat transfer technique using treated paper sheets printed with disperse dye, previously used in the heat transfer printing process at 210 °C and 60 s, for a second printing run under the same conditions. In this second transfer run, all the treated paper sheets demonstrated comparable color depth. The paper samples S8 (CPAM/0.5% SCNNP) and S10 (CPAM/3% SiO2NP) demonstrated the highest color depth transfer to polyester fabrics. This could be attributed to the ability of these treatments to improve the properties of the paper sheets by forming extra hydrogen bonds between the fibers, filing the gaps, which further act as a binder in the paper structure. This provides protection for the paper fibers from deterioration or destruction under severe transfer conditions68. Figure 11 presents a graphic representation of the heat transfer printing technique involving multifunctional, scalable, coated paper sheets (CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP).

Conclusions

Silica-based cellulose nanocrystals (SCNNP) with silica content can be obtained from rice agro-waste through an economical and environmentally friendly one-step process. This method avoids conventional extraction procedures by utilizing ammonium persulfate under microwave radiation. Microwave irradiation significantly reduces the time and energy required for SCNNP extraction from several hours to just a few minutes. The physicochemical and morphological characteristics of SCNNP and silica nanoparticles isolated from rice husks were evaluated. A corresponding peak for the carboxyl group appeared at 1724 cm-1 for SCNNP, which can be interpreted as the -C=O valence vibration of -COOH groups. The oxidation of C6 primary hydroxyl groups by APS facilitates the synthesis of carboxyl groups through the interaction of cellulose fibers with free radicals created during the chemical treatment under microwave irradiation. Distinctive vibrational peaks for Si-O-Si also emerged at wavenumbers approximately 797 cm-1 and 464 cm-1. The siloxane group stretching vibrations in the produced silica nanoparticles (SiO2NP) were responsible for the peaks at 1096, 967, 784, and 464 cm-1. A peak corresponding to SiO2 appeared at a Bragg 2θ angle of 44.48° for RH, SCNNP and SiO2NP. The CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP nanocomposites substantially functionalized paper sheets produced via bagasse waste treatment. Structural and morphological analysis of coated papers demonstrated that the SiO2NP/SCNNP nanocomposite was distributed uniformly over the paper’s cellulose matrix. Our findings further showed that the final mechanical and barrier characteristics of the paper sheets functionalized with the SiO2NP and/or SCNNP nanocomposite were highly valued. Whereas, adding CPAM/SiO2NP improved the observed tensile index, reaching its maximum (0.33 KN m/g) for the modified paper sheet S9, which contained 1% SiO2NP. The S5 (CPAM/1%SiO2NP/0.5%SCNNP), S6 (CPAM/3%SiO2NP/0.5%SCNNP), S8 (CPAM/0.5%SiO2NP), and S10 (CPAM/3%SiO2NP) coated sheets demonstrated oil resistance of approximately 1800s, which satisfies the requirements for printing applications. Modified paper sheets with (CPAM/SiO2NP and/or SCNNP) nanoparticles have a multifunctional role in UV protection for packaging and as transfer paper for the polyester printing process. Coated paper containing SiO2NP consumed less dye paste and produced higher color-density prints. Moreover, the (CPAM/SiO2NP) composite-coated papers S8 and S10 exhibited better printability, showing good stability in the second printing run.

Data availability

This published article contains all the data obtained or examined during this investigation.

References

Ezati, P. et al. Biopolymer-based UV protection functional films for food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 142, 108771 (2023).

Shen, L. et al. Effect of light treatmeat on oxidation and flavour of dry-cured Wuchang fish. Food Chem. X 22, 101464 (2024).

Vilela, C. et al. Bioactive chitosan/ellagic acid films with UV-light protection for active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 73, 120–128 (2017).

Silva, M. R. F. et al. Nanostructured transparent solutions for UV-shielding: Recent developments and future challenges. Mater. Today Phys. 35, 101131 (2023).

Darré, M., Vicente, A. R., Cisneros-Zevallos, L. & Artés-Hernández, F. Postharvest ultraviolet radiation in fruit and vegetables: Applications and factors modulating its efficacy on bioactive compounds and microbial growth. Foods 11, 653 (2022).

Gąstoł, M. & Błaszczyk, U. Effect of magnetic field and UV-C radiation on postharvest fruit properties. Agriculture 14, 1167 (2024).

Yousefi, H. et al. Intelligent food packaging: A review of smart sensing technologies for monitoring food quality. ACS Sens. 4, 808–821 (2019).

Tan, D. et al. Effects of the oxygen content and light intensity on milk photooxidation using untargeted metabolomic analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 7488–7497 (2021).

Khan, A., Ezati, P. & Rhim, J.-W. Chitosan/starch-based active packaging film with N, P-doped carbon dots for meat packaging. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 6, 1294–1305 (2023).

Matar, G. H. & Andac, M. Recent advances in sustainable biopolymer films incorporating vanillin for enhanced food preservation and packaging. Polym. Bull. 1–27 (2025).

Khan, A., Priyadarshi, R., Bhattacharya, T. & Rhim, J.-W. Carrageenan/alginate-based functional films incorporated with Allium sativum carbon dots for UV-barrier food packaging. Food Bioprocess Technol. 16, 2001–2015 (2023).

El-Shafei, A. M., Adel, A. M., Ibrahim, A. A. & Al-Shemy, M. T. Dual functional jute fabric biocomposite with chitosan and phosphorylated nano-cellulose (antimicrobial and thermal stability). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 124, 733–741 (2019).

Adel, A. M., Ahmed, E. O., Ibrahim, M. M., El-Zawawy, W. K. & Dufresne, A. Microfibrillated cellulose from agricultural residues. Part II: Strategic evaluation and market analysis for MFCE30. Ind. Crops Prod. 93, 175–185 (2016).

Nayak, S. & Mishra, C. S. K. Sustainable strategies for metal mining solid waste management through vermitechnology. In Sustainable Management of Mining Waste and Tailings 289–300 (CRC Press, 2024).

Sharma, C., Pathak, P. & Gautam, S. Transforming agri-crop residue biomass for value addition: An innovative strategy toward resilient circular economy. In Handbook of Biomass 1517–1542 (Springer, USA, 2024).

Adel, A. M., El-Shafei, A. M., Ibrahim, A. A. & Al-Shemy, M. T. Chitosan/nanocrystalline cellulose biocomposites based on date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) sheath fibers. J. Renew. Mater. 7, 567–582 (2019).

Kumari, S., Devi, S. & Kaur, B. Cellulose-based nanocomposite hydrogels with metal nanoparticles. In Cellulose-Based Hydrogells 113–139 (Elsevier, 2025).

Adel, A. M., El-Shafei, A. M., Al-Shemy, M. T., Ibrahim, A. A. & Rabia, A. M. Influence of cellulose polymorphism on tunable mechanical and barrier properties of chitosan/oxidized nanocellulose bio-composites. Egypt. J. Chem. 60, 639–652 (2017).

Caschera, D. et al. Green approach for the fabrication of silver-oxidized cellulose nanocomposite with antibacterial properties. Cellulose 27, 8059–8073 (2020).

Fatma, N., Al-Shemy, M. T., Hagag, K. H. & Adel, A. M. Fabrication of microwave silicified oxidized cellulose nanocrystals (SOCN) from Agro waste for sustainable multifunctional wool fabric coloration. J. Clean. Prod. 386, 135800 (2023).

del Rosario Herrera-Rivera, M. et al. Nanotechnology in food packaging materials: Role and application of nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 14, 21832–21858 (2024).

Bagri, F. et al. Active packaging film based on quince seed mucilage/alginate integrated with biosilica nanoparticles containing oak extract for extending the shelf life of meat. Food Packag. Shelf Life 48, 101466 (2025).

Toro, R. G. et al. Study of the effect of titanium dioxide hydrosol on the photocatalytic and mechanical properties of paper sheets. Materials 13, 1326 (2020).

Ahmed, N. M., Adel, A. M. & Diab, M. A. Packaging paper with improved mechanical and oil absorption properties based on novel ingredients. Packag. Technol. Sci. 33, 303–320 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Dual-functional Zn@ melanin nanoparticles for enhanced antibacterial activity and prolonged fruit preservation. Food Chem. 479, 143844 (2025).

El-Sakhawy, M., Adel, A. M., Diab, M. A. & Al-Shemy, M. Facile methods for the preparation of micro- and mesoporous amorphous silica from rice husk. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-01112-2 (2020).

Abd-Rabboh, H. S. M. et al. Valorization of rice husk and straw agriculture wastes of Eastern Saudi Arabia: Production of bio-based silica, lignocellulose, and activated carbon. Materials 15, 3746 (2022).

Adel, A. M., El-Shall, F. N., Diab, M. A. & Al-Shemy, M. T. Biogenic silver-doped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for multifunctional eco-designed textile printing. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 1–19 (2022).

Sun, T., Wu, C., Hao, H., Dai, Y. & Li, J. Preparation and preservation properties of the chitosan coatings modified with the in situ synthesized nano SiOx. Food Hydrocoll. 54, 130–138 (2016).

Tian, F. et al. Preservation of Ginkgo biloba seeds by coating with chitosan/nano-TiO2 and chitosan/nano-SiO2 films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 126, 917–925 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Preparation and application of chitosan/nano-TiO2/daisy essential oil composite films in the preservation of Actinidia arguta. Food Chem X 26, 102303 (2025).

Adel, A. M., Ahmed, N. M., Diab, M. A., El-Shall, F. N. & El-Shinnawy, N. Exploration on ability of printable modified papers for the application in heat sublimation transfer printing of polyester fabric. Sci. Rep. 13, 6536 (2023).

Tipsotnaiyana, N., Jarupan, L. & Noppakundilograt, S. Enhancement of flexographic print quality on bleached kraft liner using nano-silica from rice husk. Prog. Org. Coat. 87, 232–241 (2015).

Tipsotnaiyana, N., Jarupan, L. & Pechyen, C. Synthesized silica powder from rice husk for printing raw materials application. Adv. Mater. Res. 506, 218–221 (2012).

Shigrekar, M. & Amdoskar, V. A review on recent progress and techniques used for fabricating superhydrophobic coatings derived from biobased materials. RSC Adv. 14, 32668–32699 (2024).

Gravesen, J. The metric of colour space. Graph Models 82, 77–86 (2015).

Adel, A., El-Shafei, A., Ibrahim, A. & Al-Shemy, M. Extraction of oxidized nanocellulose from date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) sheath fibers: Influence of CI and CII polymorphs on the properties of chitosan/bionanocomposite films. Ind. Crops Prod. 124, 155–165 (2018).

Adel, A. M., El-Shall, F. N., Diab, M. A. & Al-Shemy, M. T. Biogenic silver-doped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for multifunctional eco-designed textile printing. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 27905–27923 (2024).

Adel, A. M., Abd El-Wahab, Z. H., Ibrahim, A. A. & Al-Shemy, M. T. Characterization of microcrystalline cellulose prepared from lignocellulosic materials. Part I. Acid catalyzed hydrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 4446–4455 (2010).

Adel, A. M. et al. Fabrication of packaging paper sheets decorated with alginate/oxidized nanocellulose-silver nanoparticles bio-nanocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 181, 612–620 (2021).

Hossain, M. I. et al. Preparation and characterization of crystalline nanocellulose from keya (Pandanus tectorius) L. fiber as potential reinforcement in sustainable bionanocomposite: A waste to wealth scheme. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 8, 100600 (2024).

Shahnani, M., Mohebbi, M., Mehdi, A., Ghassempour, A. & Aboul-Enein, H. Y. Silica microspheres from rice husk: A good opportunity for chromatography stationary phase. Ind. Crops Prod. 121, 236–240 (2018).

Haider, J. B. et al. Efficient extraction of silica from openly burned rice husk ash as adsorbent for dye removal. J. Clean. Prod. 380, 135121 (2022).

Nassar, M. Y., Ahmed, I. S. & Raya, M. A. A facile and tunable approach for synthesis of pure silica nanostructures from rice husk for the removal of ciprofloxacin drug from polluted aqueous solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 282, 251–263 (2019).

Adel, A. M. et al. Immobilization of TiO2NP@ oxidized cellulose nanocrystals for paper-based active packaging materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 231, 123270 (2023).

Zarib, N. S. M., Abdullah, S. A. & Jamil, N. H. Extraction of silica from rice husk via acid leaching treatment. In Social & Behavioural Sciences AIMC 2018 Asia International Multidisciplinary Conference 175–183 (2019).

Abdel-Bary, A. S., Tolan, D. A., Nassar, M. Y., Taketsugu, T. & El-Nahas, A. M. Chitosan, magnetite, silicon dioxide, and graphene oxide nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization, efficiency as cisplatin drug delivery, and DFT calculations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 154, 621–633 (2020).

Kordi, M., Farrokhi, N., Pech-Canul, M. I. & Ahmadikhah, A. Rice husk at a glance: From agro-industrial to modern applications. Rice Sci. 31, 14–32 (2024).

Azat, S., Korobeinyk, A. V., Moustakas, K. & Inglezakis, V. J. Sustainable production of pure silica from rice husk waste in Kazakhstan. J. Clean. Prod. 217, 352–359 (2019).

Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1051–1069 (2015).

Ji, J., Zeng, C., Ke, Y. & Pei, Y. Preparation of poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid)/silica nanocomposite microspheres and their performance as a plugging material for deep profile control. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134, 45502 (2017).

Adel, A. M., Ahmed, N. M., Diab, M. A. & Selim, M. M. The influence of TiO2/CC core/shell pigments on the properties of paper sheets. Powder Technol. 291, 437–447 (2016).

Dong, C. et al. Preparation of a novel SiO2/PMMA nanocomposite with high transparency, thermal stability, and superior surface hardness via gamma-radiation polymerization. Polym. Adv. Technol. 35, e6290 (2024).

Raghuwanshi, V. S. et al. Cationic polyacrylamide induced nanoparticles assembly in a cellulose nanofiber network. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 529, 180–186 (2018).

Zhu, Q. et al. Cross-linked chitosan/tannin extract as a biodegradable and repulpable coating for paper with excellent oil-resistance, gas barrier and UV-shielding. Prog. Org. Coat. 176, 107399 (2023).

Sani, M. A., Khezerlou, A., Tavassoli, M., Abedini, A. H. & McClements, D. J. Development of sustainable UV-screening food packaging materials: A review of recent advances. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 145, 104366 (2024).

Salama, H. E. & Aziz, M. S. A. Optimized carboxymethyl cellulose and guanidinylated chitosan enriched with titanium oxide nanoparticles of improved UV-barrier properties for the active packaging of green bell pepper. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 165, 1187–1197 (2020).

Attia, N. F., Moussa, M., Sheta, A. M. F., Taha, R. & Gamal, H. Synthesis of effective multifunctional textile based on silica nanoparticles. Prog. Org. Coat. 106, 41–49 (2017).

Xia, G. et al. Cellulose-based films with ultraviolet shielding performance prepared directly from waste corrugated pulp. Polymers 13, 3359 (2021).

Ahmed, A., Adak, B., Bansala, T. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Green solvent processed cellulose/graphene oxide nanocomposite films with superior mechanical, thermal, and ultraviolet shielding properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 1687–1697 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Enhanced production of sugars and UV-shielded lignin/PAN fiber mats from chemi-mechanical pulps. Sci. Total Environ. 861, 161090 (2023).

Plermjai, K. et al. UV shielding properties of cellulose/TiO2 composite film. Curr. Appl. Sci. Technol. 18, 111–118 (2018).

Stojanović, S., Geršak, J., Trajković, D. & Ćirković, N. Influence of sublimation transfer printing on alterations in the structural and physical properties of knitted fabrics. Color. Technol. 137, 108–122 (2021).

Sarkodie, B., Tawiah, B., Agbo, C. & Wizi, J. Status and development of transfer printing in textiles—A review. AATCC J. Res. 5, 1–18 (2018).

Sharma, M. et al. A review on cationic starch and nanocellulose as paper coating components. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 162, 578–598 (2020).

Glombikova, V. & Komarkova, P. Study on the impact of dye-sublimation printing on the effectiveness of underwear. Tekstilec 57, 133 (2014).

Elsayad, H. S. & El-Sherbiny, S. A study into the influence of paper coatings on paper properties and print quality of dye sublimation thermal prints. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 47, 122–136 (2008).

Barbash, V. A. & Yashchenko, O. V. Preparation and application of nanocellulose from non-wood plants to improve the quality of paper and cardboard. Appl. Nanosci. 10, 2705–2716 (2020).

Acknowledgements

All authors would like to thank the National Research Center (NRC), Egypt, for its financial support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The National Research Centre of Egypt provided funding for this research [Project No. 13020302].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.A.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, and Data curation Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. F.N.E-S.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M.A.D.: Methodology, Investigation, editing, Data curation and Formal analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adel, A.M., El-Shall, F.N. & Diab, M.A. Multifunctional scalable coated paper sheets for UV shielding and sublimation printing applications. Sci Rep 15, 25101 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08734-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08734-4