Abstract

To evaluate the effect of an acidic beverage and simulated gastric acid on the color stability, gloss and surface roughness of different monolithic CAD/CAM materials. Feldspathic ceramic (FC-CEREC Blocks), Lithium disilicate ceramic (LDC-UP-CAD), and resin nano-ceramic (RNC-Lava Ultimate) specimens were subjected to 3 different polishing methods (mechanical-M, glaze-G, and mechanical + glaze-MG) (n = 10). After baseline measurements of color, gloss, and surface roughness, three different immersion protocols (artificial saliva, acidic beverage, and simulated gastric acid) were applied, followed by repeated measurements. Color change was calculated by using the ∆E00 formula. The changes in gloss (ΔGU) and surface roughness (ΔRa) were calculated by subtracting the after-immersion values from the baseline measurements. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis and, post-hoc Bonferroni tests (α = 0.05). Statistically significant differences were found for ∆E00 and ΔGU values (p < 0.05), whereas differences in ΔRa measurements were insignificant (p > 0.05). The color change in the acidic beverage was higher for mechanically polished RNC, irrespective of the polishing method (p = 0.025) and immersion solution (p = 0.002). The color change in the simulated gastric acid was higher for mechanically polished LDC compared to other polishing methods (p = 0.003). All groups showed higher ΔGU values when subjected to gastric acid than artificial saliva irrespective of the polishing methods (p < 0.05). Glaze application is necessary to maintain the color of monolithic CAD/CAM restorations for patients who consume acidic beverages frequently. Clinicians should be cautious about gloss changes in monolithic restorations for bulimia nervosa patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oral cavity has an average pH of 6.7, maintained by the saliva1. However, in acidic environments, intraoral pH drops and is potentially destructive to the hard and soft tissues below pH 5.52. Acidic environments may be of intrinsic origin due to some systemic diseases such as gastroesophageal reflux and bulimia nervosa3 or extrinsic origin due to excessive exposure to acid-containing diets such as fizzy drinks, citrus fruits, or white wine4. The irreversible loss of dental hard tissues caused by repeated exposure to erosive acids of non-bacterial origin is known as dental erosion, and it may result if this acidic environment persists4.

Dental erosion causes consecutive detrimental effects on natural teeth, including loss of tooth anatomy, contour, and function, dentin hypersensitivity, and loss of vertical dimension4,5,6. The rehabilitation of such instances is mandatory in many cases, while most initial and moderate erosive damage can be treated with minimally invasive methods5. A variety of dental applications, such as minimally invasive procedures to manage erosive tooth wear, have been made possible by the development of digital dentistry and computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM)6,7. CAD/CAM monolithic dental materials such as feldspathic, lithium disilicate-based glass ceramics, and recently launched hybrid resin nano-ceramics are frequently preferred in these restorative procedures due to their mechanical, physical, and optical properties3,4,7. Acid attacks may alter these dental restorative materials’ optical and physical properties as well as tooth structures3,8. These alterations may include changes in optical properties, surface degradation, and surface roughness7,8.

The milling process of CAD/CAM restorations causes rough surfaces, which should be eliminated to improve mechanical and aesthetic properties, enhance surface quality, and prevent discoloration and plaque formation9,10,11. The surface roughness of these materials can be smoothed by mechanical polishing or glazing9. Mechanical systems offer different multi-step procedures with various grades and stages of polishers for ceramic and resin-based CAD/CAM materials9,11. Feldspathic ceramics can be mechanically polished chairside using a ceramic polishing kit immediately after restoration production, without the need for additional laboratory procedures. Alternatively, they can be polished by applying a glaze with additional firing9. On the other hand, pre-crystallized CAD/CAM lithium disilicate glass ceramics require crystallization firing to transform the lithium metasilicate into needle-formed lithium disilicate spindles12. The glazing of pre-crystallized CAD/CAM lithium disilicate materials can be accomplished along with the crystallization firing or separately13. Traditional glazing materials are glassy laminates applied on glass-ceramics to fill the superficial irregularities to smooth the surface14. The thin glassy film forms through viscous flow as glass fuses at high temperatures during furnace sintering for traditional glazing14. This firing process is not applicable for hybrid ceramics due to their methyl methacrylate content. For glazing such materials, light-curing glaze materials with resin content have been introduced11. Different glazing and polishing procedures can influence the optical properties and surface characteristics of monolithic CAD/CAM materials, particularly under erosive conditions.

The effects of acidic environments on the mechanical and optical properties of monolithic restorative materials have been previously studied. While most studies have primarily focused on mechanical resistance4,15,16,17,18,19,20some have also examined color stability, reporting a decrease3,21. Gloss, along with color stability, is an important factor influencing the aesthetic properties of ceramic materials. It is affected by the angle of light reflected from the surface, and there is a negative correlation between surface roughness and gloss22. Despite its importance, the effect of different acidic environments on gloss has been investigated in only a limited number of studies. A recent study by Kulkarni et al.21 demonstrated the harmful effects of simulated gastric acid on the gloss and color stability of feldspathic and lithium disilicate glass ceramics. However, the study did not evaluate the effect of different erosive media or polishing methods, which could significantly influence both color and gloss. The literature lacks a study that comparatively examines the effects of different erosive media on the aesthetic and surface properties of monolithic CAD/CAM materials subjected to different polishing methods.

According to these considerations, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of different erosive media (gastric acid solution and an acidic beverage) on the color stability, gloss, and surface roughness of three different monolithic CAD/CAM materials (nano-ceramic composite resin, feldspathic ceramic, and lithium disilicate-based glass ceramic) subjected to different polishing methods. The null hypothesis tested is as follows: The color, gloss, and surface roughness of CAD/CAM materials will not be affected by erosive media for all polishing methods tested.

Materials and methods

In this study, 3 types of CAD/CAM materials with A2 shade were used: feldspathic ceramic (FC: CEREC Blocks; Dentsply Sirona Dental Systems, Bensheim, Germany), lithium disilicate glass-ceramic (LDC: UP-CAD; Shenzhen Upcera Dental Technology Co, China), resin nano-ceramic (RNC: LAVA Ultimate; 3 M ESPE, St Paul, MN, USA). Table 1 gives an overview of the properties and compositions of monolithic CAD/CAM materials used in this research. All ceramic materials were subjected to 3 different polishing methods (mechanical polishing: M, glaze: G, mechanical polishing + glaze: MG). To evaluate the effect of surface roughness, color stability, and gloss of monolithic CAD/CAM materials under different conditions, 3 different immersion protocols were applied: 2 different erosive media (simulated gastric acid and an acidic beverage) and artificial saliva as a control group.

The G*Power (Version 3.1.9) program was used to determine the specimen size. The minimum required number of specimens for each group was determined to be 10 with an effect size of 0.40, 95% power, and error level of α = 0.05, resulting in a total of 270 specimens (n = 10). An additional specimen from each subgroup was prepared for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, resulting in a total of 297 specimens (N = 297).

Specimen preparation

The CAD/CAM blocks were wet sliced with a diamond saw (Micracut 201, Metkon, Bursa, Turkey) to obtain specimens with dimensions of 10 mm × 10 mm × 1.5 mm. As directed by the manufacturer, LDC specimens were set on fire for crystallization. To standardize the specimen’s surfaces, wet abrasion was performed using 600, 800, and 1200 grit silicon carbide abrasives (Buehler GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany). Then, the final dimensions of all prepared specimens were measured using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo Corporation, Kanagawa, Japan). Three subgroups were randomly selected from each material category, and surface polishing was performed by a single experienced operator (NEO) to ensure standardization among specimens. The details of applied polishing methods are shown in Table 2. After each polishing method was applied, the specimens were ultrasonically cleaned for 5 min and then immersed in distilled water at 37 °C for 24 h. Baseline measurements of color, gloss, and surface roughness were taken after the polishing procedure and prior to exposure to the erosive environment.

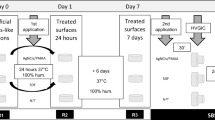

Erosive media

Three subgroups of the polished specimens were randomly selected and submerged in two erosive solutions (gastric acid and acidic beverage) and artificial saliva, which served as the control group (n = 10). Table 3 presents the properties and preparation procedures of the solutions used. Before placing the specimens in capped glass tubes containing 100 ml of each media, the pH values of the tested media were measured using a pH meter (mPA-210P; MS Tecnopon Equipamentos Especiais LTDA). For 24 h, the tubes were kept at 37 °C with constant slow shaking at 70 rpm in an incubator (Grant OLS 200, Grant Instruments Cambridge Ltd., Shepreth, UK)4,15,23. After ten minutes of ultrasonic cleaning in distilled water, all specimens were left to air dry.

Color measurement

Quantitative basic color parameters (L*, a*, and b*) of the specimens were measured using a digital spectrophotometer (VITA Easyshade® V; Vita Zahnfabrik, Germany). Measurements were performed under D65 illuminant24 by a single operator (NEO) in a light-controlled box25 against a neutral grey background26. A custom-made silicone mold was used during color measurement to minimize external light reflection on the specimen surface and ensure a consistent light angle throughout the test procedure24. The tip of the spectrophotometer was positioned perpendicular to the specimen surface, ensuring no gap between the device and the surface. Prior to each measurement, the spectrophotometer was calibrated, and each specimen was measured three times. L* (lightness), a* (green to magenta) and b* (blue to yellow) values were obtained by averaging three measurements. The color measurements of the specimens were calculated using the Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage 2000 (CIEDE2000) formula (∆E00) as follows:

∆L′, ∆C′, and ∆H′ represents the lightness, chroma, and hue differences, respectively, with corrections made using weighting factors (SL, SC, and SH) and parametric factors (kL, kC, and kH) as constants. A rotation factor (RT) was added to correct for deficiencies in the blue-violet spectrum. The ∆E00 color difference formula’s parametric factors were set to 1 for this investigation27.

Gloss measurement

A gloss meter (Novo-Gloss Trio; Rhopoint Instruments, UK) calibrated with a standard black glass provided by the manufacturer was used for the basic gloss measurements. To prevent the effects of ambient light and to ensure that the specimens remained in precisely the same location throughout many measurements, a black-opaque custom-made plastic mold was placed over them. The surface gloss values (GU) of each specimen were determined by averaging the results of three measurements taken at 60° light incident and reflection angles25. Two measurements were made before (baseline-B) and after (final-F) immersion in erosive media and artificial saliva. The change in GU was calculated according to the formula below7,8,28.

Surface roughness measurement

A contact profilometer (Perthometer M2, Mahr, Gottingen, Germany) was used to evaluate each specimen’s surface roughness (Ra). The profiler was calibrated prior to measuring each test specimen group. Three measurements in micrometres (µm) in different directions were made for each specimen (traverse length: 5.5 mm and cut: 0.8 mm), and the average of these three measurements was used for statistical analysis25. Two measurements were made before (B) and after (F) immersion in erosive media and artificial saliva. The change in Ra value for each group was calculated by using B and F values according to the formula below7,8,28:

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

One extra specimen for each subgroup (n = 27) was prepared, and SEM analysis was performed to visualize the surface irregularities of erosive media after different polishing methods. After coating the surfaces of the specimens with gold, a scanning electron microscope (EVO 40 series, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) was used for visualization at different magnifications (500 to 10,000×).

Statistical analysis

The analyses in this study were performed in IBM SPSS (version 25.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc.) program. Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests were used to verify the assumption of a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, respectively. When comparing three or more independent groups with a normal distribution, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was employed; if the data was not normally distributed, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Post Hoc Bonferroni, test was used to reveal the group or groups that made the difference. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

∆E00

The color change comparison of the test groups according to polishing methods and immersion solutions is presented in Table 4. Polishing methods MG for group FC, and G for group LDC showed higher ∆E values when immersed in the acidic beverage and gastric acid than in artificial saliva (p < 0.05). FC-G group showed the highest ∆E value when immersed in gastric acid. (p = 0.002). RNC showed the highest ∆E value for the mechanically polished and subjected to acidic beverage group (4.38 ± 2.78) irrespective of the immersion solution (p = 0.025) and polishing method (p = 0.002).

Color changes between different polishing methods were insignificant for group FC when immersed in artificial saliva (p = 0.326) and gastric acid (p = 0.985). On the other hand, when group FC is immersed in an acidic beverage, the G polishing method showed the lowest color change compared to the other two polishing methods (0.93 ± 0.87, p = 0.006). When immersed in gastric acid, the mechanically polished LDC group showed a higher ∆E value (2.53 ± 1.46) than other polishing methods (p = 0.03), for which no significant difference was found (p > 0.05).

Material comparisons based on polishing methods showed no significant difference for artificial saliva (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1). When mechanically polished specimens were immersed in the acidic beverage, group RNC showed a higher ∆E value than group LDC (4.38 ± 2.78 and 2.24 ± 1.72, respectively, p = 0.03). Also, for the glaze polishing method, group LDC showed a higher ∆E value than group FC when immersed in the acidic beverage (2.63 ± 1.96 and 0.93 ± 0.87, respectively, p = 0.03). However, the opposite findings were observed when the specimens were immersed in gastric acid (p = 0.0001).

Comparison of ΔE00 values of material groups in immersion solutions according to polishing systems. A: Artificial saliva, B: Acidic beverage, C: Gastric acid. Mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD) of ΔE00 values. (*p < 0.05 indicate statistical differences between groups.) (FC: Feldspathic ceramic, LDC: Lithium disilicate glass ceramics, RNC: Nano-ceramic resin).

ΔGU

Descriptive statistics of ∆GU values are presented in Table 5. For group FC, specimens immersed in acidic solutions showed higher gloss change than artificial saliva for all polishing methods (p < 0.002), with no difference between the two acidic solutions (p > 0.05). A similar finding was present for group LDC when G and MG polishing methods were used (p < 0.001). The M polishing method for LDC, and M and MG polishing methods for RNC groups showed higher gloss change values when immersed in gastric acid than artificial saliva and the acidic beverage (p = 0.02, p = 0.006, and p = 0.02, respectively), with no difference between the latter (p > 0.05). RNC-G group showed the highest and the lowest gloss change for gastric acid and artificial saliva, respectively (p = 0.002).

Differences in ∆GU values were insignificant when different polishing methods were used for FC, for all immersion solutions (p > 0.05). The polishing methods did not differ in ∆GU values for LDC when immersed in artificial saliva and gastric acid, and for RNC when immersed in both acidic solutions (p > 0.05). However, the MG polishing method showed higher gloss change compared to other polishing methods for LDC when immersed in the acidic beverage (p = 0.004).

The ∆GU comparisons between different materials in each solution for a particular polishing method are presented in Fig. 2. When immersed in artificial saliva, mechanically polished materials did not differ in ∆GU (p = 0.28), while the G polishing method applied FSC showed a higher ∆GU (p = 0.002), and LDC polished with MG method showed a lower ∆GU value than other materials (p = 0.005). When immersed in an acidic beverage, FSC showed a higher ∆GU value than other materials for mechanical polishing and RNC showed a lower gloss change than LDC (p = 0.005), while the other differences were insignificant (p > 0.05). Differences between ∆GU values were insignificant for all groups when immersed in gastric acid (p > 0.05).

Comparison of ΔGU values of material groups in immersion solutions according to polishing systems. A: Artificial saliva, B: Acidic beverage, C: Gastric acid. Mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD) of ΔGU values. (*p < 0.05 indicate statistical differences between groups.) (FC: Feldspathic ceramic, LDC: Lithium disilicate glass ceramics, RNC: Nano-ceramic resin, GU: Gloss unit).

ΔRa

Descriptive statistics for ∆Ra values of study groups and a representative image based on immersion solutions are presented in Table 6; Fig. 3, respectively. Differences in ∆Ra values were statistically insignificant for all comparisons between groups, polishing methods, and immersion solutions (p > 0.05).

Comparison of ΔRa values of material groups in immersion solutions according to polishing systems. A: Artificial saliva, B: Acidic beverage, C: Gastric acid. Mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD) of ΔRa values. (*p < 0.05 indicate statistical differences between groups.) (FC: Feldspathic ceramic, LDC: Lithium disilicate glass ceramics, RNC: Nano-ceramic resin, µm: Mikrometre).

SEM

Surface topography images obtained at ×2000 SEM are presented in Figs. 4, 5 and 6. Mechanically polished specimens in all groups showed surface scratch lines due to polishing discs and rubbers. However, groups RNC and FC showed surface deterioration after immersion in both erosive media. Group LDC did not show surface deterioration in erosive media, unlike other CAD/CAM materials (Fig. 5). Mechanically polished erosive media subjected RNC specimen’s surface deterioration was in the form of small, scattered pores and pits (Fig. 6), while in group FC, they were in the form of large pore aggregates (Fig. 4). Glazed only and glazed after mechanically polished specimens of groups LDC and RNC showed higher surface irregularities when subjected to an acidic beverage compared to other immersion solutions, while group FC showed similar surface topography for these polishing methods irrespective of immersion solutions.

Discussion

The current study investigated the effect of erosive media on the stability of color, gloss, and surface roughness of three different monolithic CAD/CAM materials subjected to various polishing methods. The null hypothesis that the color, gloss, and surface roughness stability of CAD/CAM materials would be maintained in the erosive media for all polishing methods tested was partially rejected. This is because differences in the color and gloss values of CAD/CAM materials subjected to different polishing methods were found for all groups, while surface roughness values were not affected by the immersion protocols tested.

This study focused on examining three monolithic CAD/CAM materials with different structures, which were selected due to their different ceramic-based composition. Dental erosion causes dental hard-tissue loss that can be restored by these materials using CAD/CAM applications. Yang et al. stated that in-vitro experiments could correlate with in-vivo results on acid resistance and abrasive changes in CAD/CAM restorative materials7. For such an in vitro study, there is no standardized protocol in the literature regarding acid concentration and exposure time that accurately simulates clinical conditions4,6,15. ISO 6872 solubility test recommends 4% acetic acid and a 16-hour exposure time at 80 °C for dental ceramics29. However, in this study, the method described by Hunt and McIntyre’s30 was used to obtain a stronger acid concentration for simulated gastric acid (HCl pH 1.2) similar to previous studies4,6,31. In this method, immersing the specimens in simulated gastric acid for 24 h is considered equivalent to the cumulative acid exposure over two years experienced by restorations in the oral environment of patients with severe reflux and bulimia nervosa4,32. A widely consumed acidic beverage with pH 2.5 was chosen as the other acidic solution4,7,16,33.

Spectrophotometers are recommended for color evaluation due to their objective and reliable measurements26,34. In the present study, Vita Easy Shade dental spectrophotometer was used for the color measurements, which was reported to represent more accurate results compared to other digital shade-matching devices35. L*, a*, and b* values obtained by this spectrophotometer were used to measure the color change (ΔE) using the CIEDE2000 formula. Studies have reported that the CIEDE2000 color difference formula is superior to the previously used CIELAB formula (∆Eab) regarding the perceptibility and acceptability of color difference36,37. The ∆Eab formula basically measures the distance between two points in color space, while the ∆E00 formula includes the luminance effect by adding SL37. Pérez Gómez et al.38 determined color difference 50%:50% thresholds for perceptibility (PT) and acceptability (AT) values of 0.87 and 1.8 for dental ceramics, respectively. Based on this information, the clinical significance of the present study’s results regarding ΔE00 values can be evaluated as follows: values at or below 0.87 are undetectable, values between 0.87 and 1.8 are acceptable, and values greater than 1.8 are unacceptable. For all monolithic CAD/CAM materials tested, mechanical polishing without glazing resulted in evident staining when subjected to acidic staining solutions. Lawson et al.39 conducted a similar study that evaluated the color change of different CAD/CAM materials in staining solutions. They concluded that staining pigments present in the acidic beverages caused discoloration, and over time, the acid may have facilitated the retention of the pigment, causing the surface of the CAD/CAM materials to deteriorate which can be influenced by the polishing method implemented. Since mechanically polished CAD/CAM materials showed significant staining compared to glazed specimens in acidic solutions, a clinical significance of our study was that for patients who frequently consume acidic beverages or suffer from bulimia nervosa, glaze application for indirect monolithic restorations can be considered an important requirement39. However, it should be noted that the long-term durability of the glaze layer under acidic conditions was not assessed in this study, as the experimental protocol simulated only two years of intraoral acid exposure. The glazing can initially minimize discoloration, yet exposure to acidic environments may lead to the degradation of the glaze layer over time40. Prolonged contact with acids may cause the dissolution of the glaze, leading to a loss of its protective properties and contributing to further material wear and discoloration40,41. Previous studies have shown that acidic beverages and gastric acid can erode the surface of dental materials and compromise protective coatings, including glazes17,18 Therefore, while glaze application can be an effective method to enhance the aesthetic stability of dental materials in the short term, its long-term effectiveness may be reduced in environments with low pH. The absence of an evaluation of the long-term effects of acidic media on glazed surfaces represents a limitation of the present study. Future research should focus on evaluating the stability and durability of glazed surfaces over extended periods of exposure to acidic conditions to better understand the impact of environmental factors on the longevity of the glaze layer and the overall material integrity.

The pH values of gastric acid (1.2–1.5) and acidic beverages (2.0–2.5) are significantly lower than the critical threshold (pH 5.5) at which dental hard tissues begin to demineralize42. Numerous studies have demonstrated that acidic environments exert a corrosive effect on both glass-based ceramic materials15,18,43 and composite resins42. In oral environments characterized by low pH and poor buffering capacity, dental ceramics are particularly susceptible to erosion, resulting in roughened and porous surfaces18. Acidic solutions can compromise the silica network of glass ceramics, which possess low stability within the glass matrix by selectively extracting alkali metal ions such as Al³⁺, Si⁴⁺, and Zr⁴37,43. On the other hand, in resin nanoceramics, which comprise ceramic particles dispersed within a polymeric matrix, the inherently hydrophilic nature of the resin phase predisposes these materials to enhanced staining when subjected to acidic media44. Hydrolytic degradation of the polymeric matrix under acid attacks consequently exposes inorganic filler particles, thereby promoting surface deterioration and increased roughness, which heightens the susceptibility to discoloration44,45. In the present study, although both simulated erosive media exhibited pH values below the critical threshold, the mechanically polished feldspathic ceramic and resin nano-ceramic exhibited higher discoloration when immersed in the acidic beverage than the simulated gastric acid. This finding may be attributable to the difference in constituents of the erosive media used since the simulated gastric acid comprises solely HCl while the acidic beverage’s constituent pigments, staining compounds, and various acids (including phosphoric acid), which may have collectively exacerbated discoloration8,46. The diverse acid constituents of the beverage may have accelerated surface degradation and subsequently facilitated pigment absorption, leading to a more pronounced color change46.

In addition to color change, gloss, which represents the amount of specular reflection of light from a surface, is one of the primary factors influencing the aesthetics of restorations8,39. The reflectivity of ceramic surfaces depends on their composition and the ability of their component atoms to retard transmitted light39. In the present study, instead of representing baseline and final gloss values, the change in gloss values was compared since all tested materials showed a significant reduction in gloss and an increase in gloss change after immersion in acidic solutions, especially in simulated gastric acid. Moreover, gloss change in simulated gastric acid did not differ according to the polishing method or CAD/CAM material used. This can be associated with the surface degradation of dental materials due to the low pH associated with the buffering capacity of acidic solutions8,47. In line with our findings, Ozera et al.8 stated that the gloss of restorative materials was reduced significantly after exposure to acidic beverages. The authors associated this finding with the presence of phosphoric acid in the composition of acidic beverages and their pH level, which is 2.5. The acidic beverage used in our study had a pH of 2.5, and HCl, as the simulated gastric acid solution, had a pH of 1.2. The higher acidic content of HCl used in the present study may have caused destabilization of the external gloss of all monolithic CAD/CAM materials4,39. Based on this finding, it can be assumed that the gloss change of monolithic CAD/CAM materials is more dependent on the intraoral pH rather than the polishing method or material content used. Therefore, a significant decrease in gloss can be expected for monolithic restorations in bulimia nervosa patients during their intraoral service time.

Low pH and inadequate buffering capacity in oral environments can lead to the erosion of dental ceramics and cause a rough surface that can reduce brightness due to random light scattering9,28. In the present study, the difference between the baseline and after applying study protocol values was evaluated for surface roughness to ease the understanding of the results. However, no statistical significance was detected for either of the study protocols. In line with these findings, previous studies are present that reported no significant effect of erosive acids on the surface roughness of CAD/CAM materials despite color and gloss changes. The measurement method used for surface roughness may affect the results. Thus, these findings should be interpreted cautiously.

Although differences in surface roughness change were insignificant, SEM examination revealed surface topography variations. The deterioration in mechanically polished feldspathic ceramic and resin nano-ceramic surfaces was apparent when subjected to acidic solutions while lithium disilicate showed generally smooth surfaces. These results can be explained by how acids initially affected the ceramic materials, dissolving and desorbing glass particles16,17,28. A possible reason why these findings were not reflected in surface roughness values could be that these images represent early signs observed in SEM analysis.

Intraoral conditions, particularly saliva’s buffering effect, may mitigate the negative effects of low pH values caused by acid attacks2,3,6. A limitation of the present study was the in-vitro setup, which does not fully replicate the dynamic pH fluctuations and biological interactions occurring in the oral cavity3. Additionally, the use of a colored acidic beverage introduces a potentially confounding variable, as the observed color changes may be influenced by both the acidity of the solution and its pigments. Another limitation is that while surface roughness was evaluated, volumetric material loss due to erosive wear was not directly quantified. Future studies should incorporate three-dimensional surface analysis techniques to assess both surface topography and material loss. Moreover, in-vitro studies simulating intraoral conditions, using alternative colorless acidic solutions, and investigating different finishing and polishing protocols could enhance the clinical relevance of the findings.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this in-vitro study, the following conclusions were drawn:

Color stability: The results demonstrated that mechanical polishing alone resulted in significant color changes for feldspathic ceramic and resin nano-ceramic after exposure to an acidic beverage, and for lithium disilicate ceramic after exposure to simulated gastric acid. The glaze application in monolithic CAD/CAM materials helped mitigate these changes.

Gloss retention: Gloss values significantly decreased after exposure to acidic environments, particularly in polished groups. This suggests that intraoral exposure to acidic beverages or gastric acid may lead to a perceptible gloss reduction in monolithic CAD/CAM restorations.

Surface roughness and topography: While quantitative roughness values did not significantly change after acidic exposure, qualitative surface topography analyses indicated that all tested materials exhibited alterations in surface morphology, potentially affecting their long-term performance.

These findings highlight the impact of acidic conditions on CAD/CAM materials and emphasize the importance of material selection and surface treatment strategies in restorative dentistry.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Baliga, S., Muglikar, S. & Kale, R. Salivary pH: A diagnostic biomarker. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 17, 461–465 (2013).

Cruz, M. E. M. et al. Influence of simulated gastric juice on surface characteristics of CAD-CAM monolithic materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 123, 483–490 (2020).

Elraggal, A., Afifi, R. & Abdelraheem, I. Effect of erosive media on microhardness and fracture toughness of CAD-CAM dental materials. BMC Oral Health. 22, 191 (2022).

Schlueter, N., Jaeggi, T. & Lussi, A. Is dental erosion really a problem? Adv. Dent. Res. 24, 68–71 (2012).

Sulaiman, T. A. et al. Impact of gastric acidic challenge on surface topography and optical properties of monolithic zirconia. Dent. Mater. 31, 1445–1452 (2015).

Yang, H., Lu, Z. C., Attin, T. & Yu, H. Erosion of CAD/CAM restorative materials and human enamel: an in vitro study. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 119, 104503 (2021).

Ozera, E. H. et al. Color stability and gloss of esthetic restorative materials after chemical challenges. Braz Dent. J. 30, 52–57 (2019).

Carrabba, M. et al. Effect of finishing and Polishing on the surface roughness and gloss of feldspathic ceramic for chairside CAD/CAM systems. Oper. Dent. 42, 175–184 (2017).

Siddanna, G. D., Valcanaia, A. J., Fierro, P. H., Neiva, G. F. & Fasbinder, D. J. Surface evaluation of resilient CAD/CAM ceramics after contouring and Polishing. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 33, 750–763 (2021).

Ozer, N. E. & Oguz, E. I. Influence of different finishing-polishing procedures and thermocycle aging on the surface roughness of nano-ceramic hybrid CAD/CAM material. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 26, 604–611 (2023).

Lohbauer, U. et al. Glass science behind lithium silicate glass-ceramics. Dent. Mater. 40, 842–857 (2024).

Jurado, C. A. et al. Ceramic and composite Polishing systems for milled lithium disilicate restorative materials: A 2D and 3D comparative in vitro study. Materials (Basel) 15 (15), 5402 (2022).

Sarthak, K., Singh, K., Bhavya, K. & Gali, S. Glazing as a bonding system for zirconia dental ceramics. Mater. Today Proc. 89, 24–29 (2023).

Elraggal, A., Afifi, R., Alamoush, R., Raheem, R. A., Watts, D. C. & I. A. & Effect of acidic media on flexural strength and fatigue of CAD-CAM dental materials. Dent. Mater. 39, 57–69 (2023).

Alghamdi, W. S. et al. Influence of acidic environment on the hardness, surface roughness and wear ability of CAD/CAM resin-matrix ceramics. Materials (Basel), 15 (17), 6146 (2022).

Alnasser, M. et al. Effect of acidic pH on surface roughness of esthetic dental materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 122, 567e561–567e568 (2019).

Esquivel-Upshaw, J. F., Dieng, F. Y., Clark, A. E., Neal, D. & Anusavice, K. J. Surface degradation of dental ceramics as a function of environmental pH. J. Dent. Res. 92, 467–471 (2013).

Alnsour, M. M., Alamoush, R. A., Silikas, N. & Satterthwaite, J. D. The effect of erosive media on the mechanical properties of CAD/CAM composite materials. J Funct. Biomater, 15 (10), 292 (2024).

Scotti, N. et al. Influence of low-pH beverages on the two-body wear of CAD/CAM monolithic materials. Polymers (Basel) 13 (17), 2915 (2021).

Kulkarni, A., Rothrock, J. & Thompson, J. Impact of gastric acid induced surface changes on mechanical behavior and optical characteristics of dental ceramics. J. Prosthodont. 29, 207–218 (2020).

KA, A. A. & Rayyan, M. R. Effect of simulated tooth brushing on the surface gloss of monolithic all-ceramic restorations: an in vitro study. Clin. Oral Investig. 29, 133 (2025).

Egilmez, F., Ergun, G., Cekic-Nagas, I., Vallittu, P. K. & Lassila, L. V. J. Does artificial aging affect mechanical properties of CAD/CAM composite materials. J. Prosthodontic Res. 62, 65–74 (2018).

Seyidaliyeva, A. et al. Color stability of polymer-infiltrated-ceramics compared with lithium disilicate ceramics and composite. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 32, 43–50 (2020).

de Castro, E. F. et al. Effect of build orientation in gloss, roughness and color of 3D-printed resins for provisional indirect restorations. Dent. Mater. 39, e1–e11 (2023).

Ardu, S., Braut, V., Di Bella, E. & Lefever, D. Influence of background on natural tooth colour coordinates: an in vivo evaluation. Odontol 102, 267–271 (2014).

Pecho, O. E., Ghinea, R., Alessandretti, R. & Pérez, M. M. Della bona, A. Visual and instrumental shade matching using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulas. Dent. Mater. 32, 82–92 (2016).

Papathanasiou, I., Zinelis, S., Papavasiliou, G. & Kamposiora, P. Effect of aging on color, gloss and surface roughness of CAD/CAM composite materials. J. Dent. 130, 104423 (2023).

Standardization, I. O. & Technical Committee ISO/TC 106, D. Dentistry: Ceramic Materials (ISO 6872:2015)European Committee for Standardization,. (2015).

D, McIntyre JM. The development of an in vitro model of dental erosion. J Dent. Res. 71, 985 (1992).

João-Souza, S. H. et al. Toothpaste factors related to dentine tubule occlusion and dentine protection against erosion and abrasion. Clin. Oral Investig. 24, 2051–2060 (2020).

Hetherington, M. M., Altemus, M., Nelson, M. L., Bernat, A. S. & Gold, P. W. Eating behavior in bulimia nervosa: multiple meal analyses. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 60, 864–873 (1994).

Lemos, C. A., Mauro, S. J., Dos Santos, P. H., Briso, A. L. & Fagundes, T. C. Influence of mechanical and chemical degradation in the surface roughness, gloss, and color of microhybrid composites. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 18, 283–288 (2017).

Elter, B., Aladağ, A., Çömlekoğlu, M. E., Dündar Çömlekoğlu, M. & Kesercioğlu A. colour stability of sectional laminate veneers: A laboratory study. Aust Dent. J. 66, 314–323 (2021).

Kim-Pusateri, S., Brewer, J. D., Davis, E. L. & Wee, A. G. Reliability and accuracy of four dental shade-matching devices. J. Prosthet. Dent. 101, 193–199 (2009).

Ayaz, E. A. & Ustun, S. Effect of staining and denture cleaning on color stability of differently polymerized denture base acrylic resins. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 23, 304–309 (2020).

Yılmaz, K., Özdemir, E. & Gönüldaş, F. Effect of immune-boosting beverage, energy beverage, hydrogen peroxide superior, Polishing methods and fine-grained dental prophylaxis paste on color of CAD-CAM restorative materials. BMC Oral Health. 24, 1104 (2024).

Pérez Gómez, M. M., Pecho, O., Ghinea, R. I. & Pulgar, R. & Della bona, A. Recent advances in color and whiteness evaluations in dentistry. Curr Dent 01, 23-29 (2019).

Lawson, N. C. & Burgess, J. O. Gloss and stain resistance of ceramic-polymer CAD/CAM restorative blocks. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 28 (Suppl 1), S40–45 (2016).

Yang, H., Yang, S., Attin, T. & Yu, H. Effect of acidic solutions on the surface roughness and microhardness of indirect restorative materials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Prosthodont. 36, 81–90 (2023).

Kukiattrakoon, B., Hengtrakool, C. & Kedjarune-Leggat, U. Chemical durability and microhardness of dental ceramics immersed in acidic agents. Acta Odontol. Scand. 68, 1–10 (2010).

Cengiz, S., Sarac, S. & Özcan, M. Effects of simulated gastric juice on color stability, surface roughness and microhardness of laboratory-processed composites. Dent. Mater. J. 33, 343–348 (2014).

Alencar-Silva, F. J. et al. Effect of beverage solutions and toothbrushing on the surface roughness, microhardness, and color stainability of a vitreous CAD-CAM lithium disilicate ceramic. J Prosthet Dent 121, 711.e711-711.e716 (2019).

Yılmaz, M. N. & Gul, P. Susceptibility to discoloration of dental restorative materials containing dimethacrylate resin after bleaching. Odontology 111, 376–386 (2023).

Ceci, M. et al. Discoloration of different esthetic restorative materials: A spectrophotometric evaluation. Eur. J. Dent. 11, 149–156 (2017).

de Sales-Peres, C., Magalhães, S. H., de Andrade Moreira Machado, A. C., Buzalaf, M. A. & M. A. & Evaluation of the erosive potential of soft drinks. Eur. J. Dent. 1, 10–13 (2007).

Tanthanuch, S. et al. Surface changes of various bulk-fill resin-based composites after exposure to different food-simulating liquid and beverages. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 30, 126–135 (2018).

Aframian, D. J., Ofir, M. & Benoliel, R. Comparison of oral mucosal pH values in bulimia nervosa, GERD, BMS patients and healthy population. Oral Dis. 16, 807–811 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors represent gratitude to Ayça Ölmez for his support as the statistical analyzer, Mr. Mustafa Yeşil for his support as laboratory technician, and Dr Elif Yildiz from Ankara University Institute of Nuclear Sciences for SEM analysis.

Funding

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: N.E.Ö., E.İ.O.; Methodology: N.E.Ö., E.İ.O.; Software: N.E.Ö.; Validation: N.E.Ö., E.İ.O.; Investigation: N.E.Ö., E.İ.O.; Resources: N.E.Ö.; Data curation: N.E.Ö., E.İ.O.; Writing: N.E.Ö., E.İ.O.; Visualization: N.E.Ö., E.İ.O. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This in-vitro study does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Özer, N.E., Oğuz, E.İ. The Effect of Erosive Media on Color Stability, Gloss, and Surface Roughness of Monolithic CAD/CAM Materials Subjected to Different Polishing Methods. Sci Rep 15, 23774 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08773-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08773-x