Abstract

In order to realize the continuous chord bending of the wing and consider the material deformation limitation, a trailing-edge curvature variable wing section combining rigid and flexible structures is proposed. In the wing configuration design, the optimal lift-to-drag ratio is used as the optimization objective, and the wing section mean line is parameterized to obtain the optimal rigid-flexible hybrid deformation configuration. The aerodynamic characteristics of hybrid rigid-flexible deflection wing and traditional rigid deflection wing were compared by flow field calculation. Under different angles of attack, the hybrid deflection airfoil has better aerodynamic performance, with the lift coefficient increasing by up to 1.66 times and the lift-to-drag ratio increasing by up to 2.86 times. Under various flight conditions, the rigid-flexible hybrid wing requires a smaller deflection angle and a better wing configuration than the traditional wing. Under high-angle deflection conditions such as landing, the lift-to-drag ratio of the rigid-flexible hybrid wing is increased by 78%, while delaying flow separation (x/c = 0.8) and reducing trailing-edge vortices, thereby improving aerodynamic efficiency. Additionally, for the flexible deformation part in the rigid-flexible hybrid wing, pneumatic muscles are used as flexible actuators, and a proportional integral sliding mode control method based on a nominal model is established. A test platform was built to control the deformation of the flexible part of the wing rib, and the ability of the flexible part to achieve the target curvature within the range of elastic deformation was verified. The actual deformation curve is very consistent with the target deformation curve. The dynamic performance test of the control method and parameters proves the rationality and effectiveness of the control system design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fixed-wing aircrafts are required to maintain specific wing configurations in different flight conditions to meet the aerodynamic demands during takeoff, climb, cruise, maneuvering, descent, landing, and taxiing. Currently, they can adjust only their flight states through different pilot-controlled systems, such as flaps, ailerons, rudders, and elevators. Engineers have long pursued the goal of designing an aircraft that, like a bird, can adjust its shape based on flight posture to maintain the optimal aerodynamic efficiency. Accordingly, the concept of morphing aircraft was born. Unlike traditional aircrafts, morphing aircrafts can change their shapes, according to different operational conditions, for achieving the design goal of integrating various aerodynamic layouts on a single platform. Adaptive morphing of aircrafts can effectively improve flight efficiency, save fuel, and achieve various objectives, such as enhancing the lift-to-drag ratio, optimizing the aerodynamic characteristics, reducing the radar cross-section, and lowering the operational costs. Among the research on morphing aircrafts, the study of morphing wings is particularly critical. Depending on design requirements, research on morphing wings is divided into in-plane morphing and out-of-plane morphing. The in-plane morphing often involves the changing of the wingspan or sweep angle to improve the flight efficiency, while the out-of-plane morphing typically adjusts the wing camber to modify the lift-to-drag ratio of an aircraft and ultimately to achieve its design objectives. Consider flaps as an example, traditional flaps rely on complex driving mechanisms to change the camber of the trailing edge. These deformation devices are not only structurally bulky but also achieve camber changes through rigid deflections, inevitably resulting in some gaps within the mechanisms. This leads to discontinuities and irregularities in camber changes, significantly affecting the aerodynamic efficiency of an aircraft. With the continuous advancement of the aerospace technology, the research on achieving smooth and flexible chordwise morphing wings has become a new trend in wing structural deformation.

For chordwise morphing wings, three key aspects are crucial: design of morphing wing ribs, control methods for actuation, and flexible skin structures1. Since 2010, NASA has collaboration with Boeing to launch the " Variable Camber Continuous Trailing Edge Flap " project, aimed at developing a novel, smooth, three-segment morphing wing trailing edge actuated by a combination of shape memory alloys and distributed motors2. This flap system will enable an aircraft to achieve the optimal lift-to-drag ratios across multiple mission profiles, thereby reducing fuel consumption. Lu et al.3, Miller et al.4, and Kota et al.5 employed compliant mechanisms to design adaptive trailing edge flaps, and their ability to change the camber during flight was tested through dynamic flight trials on an experimental aircraft. Recently, NASA has adopted the concept of cellular array structures to design and manufacture ultralight, yet sufficiently stiff and strong, morphing wings6. Sinapius et al.7 proposed a “finger” deformation concept, which utilizes a traditional mechanical design with an internal four-bar linkage to achieve single-degree-of-freedom actuation. Woods et al.8 proposed the “fishbone” concept, which applies biomimetic principles to design the morphing camber. Christine9 designed and manufactured a structure with zero Poisson’s ratio, integrating a fishbone skeleton with an internal honeycomb structure into a single unit via the 3D printing technology, to solve the issue of mismatched deformation between the skeleton and flexible skins. In the European “Clean Sky” project10, three types of morphing structures were developed for regional jets: drooped nose, multifunctional flaps, and adaptive winglets. These structures allow aircrafts to optimize the aerodynamic efficiency by adjusting their shapes in real time according to the flight conditions. The effectiveness of these morphing devices was evaluated on laminar wings. Wang et al.11 used zero Poisson’s ratio honeycomb-structured flexible materials for skin, and designed a structure in which curved beams and planar disks drive trailing edge deflection, further exploring its multidisciplinary design and optimization methods. Snow et al.12 developed a flexible wing. The wing cannot be disassembled and integral structure made using 3D printing technology. The performance and stability of the wing were discussed, and prospects were proposed. Mkhoyan et al.13 designed and developed a self-morphing wing, and proposed a novel concept of distributed morphing, where the wing can control spanwise distribution of lift to ensure optimal wing performance. Jenett et al.14 designed a morphing wing based on discrete modular units, allowing continuous lateral twisting deformation, thereby improving the roll efficiency of the wing.

Deformation structure design of aircraft wing

In terms of structural deformation, both three-segment flaps and finger-type morphing wings rely on small-scale linear segment structures or cellular structures to approximate the target camber, which makes it difficult to achieve true curved deformation. Compliant mechanisms, which convert input loads into an output displacement through elastic deformation while storing a part of the input energy as strain energy. These mechanisms naturally enable smooth and continuous deformation in the desired direction, additionally reducing the number of components required in the structure. This replacement of traditional mechanical transmission joints reduces wear and tear on the mechanism, and enhances the driving efficiency.

Driver for deformable structure

Once the method of structural deformation is determined, the selection of actuators and their compatibility with the structure become crucial. New driving technologies, such as shape memory alloys, piezoelectric ceramics, and ultrasonic motors, are gradually replacing traditional actuators and gaining increasing attention. Shape memory alloys are characterized by high strain and stress. However, these metal wires require significant time to heat and cool. Their performance is also highly affected by environmental factors, leading to unstable driving performance and low efficiency. Additionally, the fatigue life of the metal wires severely limits the service life of the actuators. Piezoelectric materials are widely used due to their high sensitivity and design flexibility. But their limited deformation restricts them to be applicable in small aircrafts and model airplanes only, making it challenging to meet the requirement of large deformation in larger aircrafts. Ultrasonic motors have the advantages of small size and minimal influence from external factors. However, because of a small size, their output is also limited, and they are typically used only in small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). To achieve a smooth and gradual downward bending deformation, multiple motors are often required to drive different wing rib segments along the chord direction of the wing, which inevitably increases the weight of the structure, potentially offsetting the aerodynamic benefits of flexible structures. On the other hand, pneumatic muscles, a new type of flexible actuator, have high energy conversion efficiency and a large actuation stroke, with a contraction stroke of up to 20% of the initial length15. Additionally, they are compact, flexible, and bendable, allowing them to be placed within the complex and confined spaces of wing boxes.

Driver control method

In order to quickly, precisely, and stably deform the morphing wing structure to the angles required by flight conditions, a carefully designed control method for actuators is necessary. There are three main control strategies for controlling structural deformation, namely sliding mode variable structure control, adaptive control, and robust control. Among them, the sliding mode control can be designed according to different application scenarios16,17. It is independent of object parameters and perturbations, so that the controlling of variable structure control becomes faster and insensitive to the changes in the system parameters and disturbances, and does not require accurate dynamic models and dedicated multi-variable decoupling or online identification. Sliding mode variable structure control is particularly suitable for robotic manipulator control due to its robustness against nonlinear dynamics, parameter variations, and external disturbances, ensuring precise trajectory tracking while effectively suppressing chattering-induced uncertainties18.

In light of above three pionts, this paper adopts compliant mechanisms as the chordwise morphing wing structure, considering that the elastic deformation of material is capable to balance the need of lift and optimal lift-to-drag. A hybrid rigid-flexible deflecting wing trailing edge is introduced, which is driven by pneumatic muscles using sliding mode variable structure control.

Firstly, the morphing configuration is geometrically parameterized based on the mean line of the airfoil. With the lift-to-drag ratio as the optimization objective, the optimal camber configuration is determined using a genetic algorithm combined with the calculation method for wing flow field parameters, and the lift-to-drag ratio of the optimized configuration are validated through computational fluid dynamics. The lift coefficient, lift-to-drag ratio, and flow field characteristics of the traditional rigid deflected trailing edge and hybrid rigid-flexible trailing edge are compared under different flight conditions.

Secondly, The structural optimization design of the trailing edge of the wing rib is briefly introduced. The rigid deflection part is driven by a servo motor and a linkage mechanism. The flexible part adopts a topology optimization method based on the load path method to design the structure.

Thirdly, In the study of control methods, the pneumatic muscle is used as the actuator for flexible structure, and its mechanics are modeled first. then, the pseudo-rigid body modeling of the flexible large deformation structure is adopted, which is equivalent to the manipulator for dynamic modeling. Afterwards, the proportional integral (PI) sliding mode variable structure control method, based on the nominal model, is combined to accurately control the deformation of the flexible section structure by its adjusting control parameters. Finally, the effectiveness of the method is verified experimentally.

Methods and results

Parametric description and optimum design of morphing wing configuration

The basic design of the morphing wing trailing edge consists of three parts: actuator input, structural form, and deformation output. The actuator input generally refers to the location of the actuation on the structure and the driving method, which can be categorized into centralized single-point drive and distributed drive. The structural form is typically obtained through an empirical design or topology optimization. The deformation output refers to the deformation state of the structure under the action of the actuator. For chordwise morphing trailing edges, the deformation output is the outer contour of the wing rib structure. Flaps installed at the trailing edge of the wing usually occupy 25% to 35% of the total chord length of the wing cross-section. In this work, for the design of the variable wing rib structure, the flap system of a medium-range and medium-sized transport aircraft was used as a design reference, with a total wing chord length of 3.33 m, and the morphing trailing edge section measuring 1 m, accounting for 30% of the chord length. The target deflection angle of the chordwise morphing trailing edge was set to 30°. The NACA0012 airfoil was selected as the baseline reference airfoil for the design, and the chosen material was the 7075-T6 high-strength aluminum alloy commonly used in aircraft design.

Preliminary finite element analysis revealed that, if the entire trailing edge morphing section were designed as a flexible structure when the structure deflected to the target angle, the stresses on the upper and lower wing surfaces would exceed the allowable stress of the material. Further analysis of the requirement of continuous camber deformation of the airfoil trailing edge indicated that its mean line deformation was similar to the bending deformation of a loaded cantilever beam. The initial and tip sections of the mean line deformation in a cantilever beam-type trailing edge exhibited similar slope distributions. Therefore, for balancing the need for lift enhancement and achievement of optimal lift-to-drag ratio19, this paper proposes a hybrid rigid-flexible morphing wing rib design scheme, as shown in Fig. 1, considering the capability of elastic deformation of the wing rib material. In the chordwise morphing trailing edge section, rigid, flexible, and follow-up structures are alternately arranged, accounting for 30%, 40%, and 30% of the entire trailing edge, respectively.

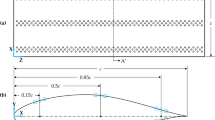

Based on the design scheme of the hybrid rigid-flexible morphing wing rib trailing edge, as shown in Fig. 1, its deflection is described using the mean line. At this point, the relatively complex problem of parameterizing the airfoil is simplified into a curve parameterization problem. In order to ensure the continuity and smoothness in the variation of the camber, as well as to increase the diversity of camber curve variation descriptions, a cubic spline as expressed by Eq. (1) is used to describe the mean line of the trailing edge section.

In Eq. (1), \((x_{start} ,y_{start} )\) and \((x_{end} ,y_{end} )\) represent the coordinates of the initial and final deflection points of the mean line, respectively, and \(l\) denotes the length of the mean line in the morphing trailing edge section, and \(\theta_{2}\) represents the equivalent deflection angle of that section.

The mean line of the airfoil under the hybrid rigid-flexible structure is shown in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 2, all of points m0 through m5 are located on the mean line of the airfoil, where m0 represents the initial point of the morphing section of the wing, and m5 represents the point of the trailing edge. Points m1 and m4 are the junctions between the rigid and flexible sections, and points m1 through m4 equally divide the mean line of the flexible section. Since the advantage of the chordwise morphing airfoil lies in the improvement of its lift-to-drag ratio compared to traditional airfoils, the evaluation function S for the optimal morphing configuration is defined as the maximum lift-to-drag ratio of the airfoil, as expressed by Eq. (2).

where CL represents the lift coefficient, and CD represents the drag coefficient.

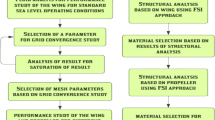

In this work, a target deflection angle of 30° was used for the trailing edge of the wing, corresponding to the landing condition (maximum deflection angle) of the aircraft. Using a genetic algorithm and aerodynamic calculation of a two-dimensional airfoil, the optimal mean line parameters were optimized with the maximum lift-to-drag ratio of the morphing configuration as the optimization objective. The calculation process in detail is shown in Fig. 3.

Considering the limitation of the material strength, the maximum allowable equivalent chordwise camber deflection angle for the flexible and follow-up sections was set to 15°. After normalizing the optimized mean line coordinates, the final morphing configuration was obtained, as shown in Fig. 4.

Analysis of aerodynamic characteristics

Based on the optimized airfoil of the hybrid rigid-flexible morphing trailing edge and the traditional rigid deflection airfoil, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis was conducted to compare and analyze their flow field characteristics and aerodynamic properties. The computational grid is shown in Fig. 520. The computational grid consists of 31,126 cells. The residuals of all parameters are less than 0.001, indicating good computational convergence.

The calculation of flow field is performed using the \(k-\omega\) SST turbulence model, considering an ideal gas at a temperature of 300 K as the fluid medium, a reference standard atmospheric pressure of 101,325 Pa, a Mach number of 0.2, and a reference chord length of 1000 mm.

Figure 6 shows the variation in the lift coefficient with the angle of attack for two different deflection methods at a fixed trailing edge deflection angle of 30°. As shown in Fig. 6, under the same trailing edge deflection angle, the lift coefficient of the hybrid rigid-flexible deflection method is consistently higher than that of the rigid deflection airfoil. This difference is more pronounced at negative angles of attack. The smoother and more continuous pressure distribution in the trailing edge region of the hybrid deflection method results in a larger enclosed area, thereby producing a more significant lift enhancement effect. At angles of attack of -4° and 8°, the lift coefficients of the hybrid deflection airfoil are 1.66 and 1.12 times of those of the traditional rigid deflection airfoil, respectively.

Figure 7 shows the variation in the lift-to-drag ratio with the angle of attack for two different deflection methods at a fixed trailing edge deflection angle of 30°. As shown in Fig. 7, under the same trailing edge deflection angle, the lift-to-drag ratio of the hybrid rigid-flexible deflection airfoil is consistently higher than that of the rigid deflection airfoil, though the advantage of the hybrid deflection diminishes as the angle of attack increases. At angles of attack of -4° and 8°, the lift-to-drag ratios of the hybrid deflection airfoil are 2.86 and 1.37 times of those of the traditional rigid deflection airfoil, respectively.

In order to more comprehensively verify the lift-to-drag ratio of the hybrid deflection airfoil, the actual flight conditions of a transport aircraft were considered. The lift of the unit span wing during normal cruising was set as the target, and the aerodynamic calculation method for airfoil were used to optimize the deflection configurations for both deflection methods under low-speed cruising and landing conditions, so at to achieve the target lift, as presented in Table 1. These configurations were then validated using CFD.

As shown in Table 1, in order to achieve the target lift under low-speed cruising conditions, the traditional rigid deflection airfoil requires a 7.3° deflection of the entire trailing edge, which occupies 30% of the chord length. At this point, the lift-to-drag ratio is 43.78. In contrast, the hybrid rigid-flexible airfoil does not require any rigid deflection. It drives only the flexible and follow-up sections, which occupy 21% of the chord length, to achieve an equivalent downward deflection of 8.7° to reach the target lift. The lift-to-drag ratio at this point is 45.53, representing a 3.9% increase compared to the traditional rigid deflection airfoil, thus improving the cruising efficiency. Under landing conditions, which typically correspond to the maximum trailing edge deflection, the traditional rigid deflection airfoil needs to deflect the entire trailing edge by 29° to achieve the target lift, resulting in a lift-to-drag ratio of 9.03. However, the hybrid airfoil requires only rigid deflection of 3.78° and flexible section deflection of 15°, with an overall equivalent trailing edge deflection of 16.05° to achieve the target lift. At this point, the lift-to-drag ratio becomes 16.11, representing a 78.41% increase compared to that in the traditional rigid deflection airfoil. It is evident that the lift-to-drag advantage becomes more pronounced at larger deflection angles.

Figures 8 and 9 show that under low-speed cruising conditions, both deflection methods exhibit similar pressure distribution, velocity distribution, and flow field characteristics. Due to the small angle of attack and trailing edge deflection, no significant flow separation occurs at the rear of the airfoil.

Figure 10 shows the pressure distribution contours for both configurations under landing conditions. Comparing Fig. 10a and b, it is found that the low-pressure region at the trailing edge formed by the hybrid rigid-flexible deflection airfoil is significantly smaller than that formed by the traditional rigid deflection airfoil. Figure 11 shows the velocity contours and streamlines for both configurations under the same conditions. Figure 11a shows that the point of airflow separation at the trailing edge of the hybrid deflection airfoil is located at \(x/c = 0.8\), while Fig. 11b shows that the same of the traditional rigid deflection airfoil is located at \(x/c = 0.57\). Furthermore, the vortex structure formed by the airflow separation at the trailing edge of the traditional rigid deflection airfoil as shown in Fig. 11b is significantly larger than that of the hybrid deflection airfoil as shown in Fig. 11a. This indicates that the traditional rigid deflection airfoil experiences premature airflow separation, severely affecting the aerodynamic efficiency; whereas the hybrid rigid-flexible deflection airfoil is less prone to airflow separation, with the separation point located closer to the trailing edge, resulting in a better aerodynamic efficiency.

Structural optimization method of variable camber wing rib compliant section

Based on the aerodynamic design scheme determined by the optimal morphing configuration as shown in Fig. 4, the wing rib structure was designed. The detailed process of optimizing the hybrid rigid-flexible wing structure is omitted in this paper, and only the design principles and results are briefly described.

Using 7075-T6 high-strength aluminum alloy, commonly used in aerospace, as the design material, the topology of the wing rib structure is optimized based on the load path analysis. In its initial layout, the load path method is similar to the basic structural optimization method, where feature points within the design domain are connected based on the load path transfer form. The diversity of the topology is controlled by the position and number of intermediate points. Firstly, an appropriate number of nodes are arranged within the design domain, and the initial topology is structured through a fully constrained configuration, as shown in Fig. 12.

Then, the load paths are parameterized and discretized to form different paths from the load input points to the output points. Next, appropriate design variables, such as path numbers and path weights, are selected. Combining each load transmission path with finite element analysis and optimization algorithms, the optimal load paths from the input points to the output points are obtained under given constraints. The load path method algorithm flowchart is given in Fig. 13.

Finally, all the structures covering these paths are combined to obtain the final optimized topology. Further, the size and shape of the optimized topology are optimized separately, ultimately yielding the structural form of the hybrid rigid-flexible morphing wing rib, as shown in Fig. 14.

Pneumatic muscle and control method

For the rigid-flexible hybrid variable bending trailing edge rib considered in this study, different types of drives are suitable for different design objectives. The rigid deflection section can be controlled accurately by a servo motor driven and a crank linkage mechanism to precisely control any downward bias. According to the analysis of the deformation characteristics of the flexible section, the overall downward bias process is similar to the deformation of the ancient long bow, and mainly depends on the variable section crank beam running through the entire flexible section. Therefore, the flexible section needs to be driven in a manner similar to a long bow.

The pneumatic muscle is pneumatically powered, which moves in the same way as a human muscle. It is mainly made up of a rubber cylinder in the middle and a stiff outer layer of wound fibers21. The pneumatic muscle can be placed in complex and small rib spaces due to its flexible, bendable and miniaturized structure. Its weight is greatly reduced due to the use of rubber material, which helps in reducing the overall weight of the aircraft structure.

Therefore, the drive control of the downward bias deformation in the flexible section of the rigid-flexible hybrid trailing edge is the focus of this study, whose control flow is shown in Fig. 15.

As can be seen from Fig. 15, in addition to the design of the controller, a mathematical modelling of the pneumatic muscle drive and rib flexible section structure is also required.

Firstly, a mathematical model of the driving force of the pneumatic muscle was established to quantify the actuation capability of the drive, which was also the basis for building a simulation model of the variable bending drive control system for the flexible wing rib structure22. The pneumatic muscle was used as the research object, as shown in Fig. 16.

The Newton’s second law of motion gives the kinetic model of the system as expressed by Eq. (3).

where \(m\) and \(L\) are the mass and real-time length of the pneumatic muscle, respectively; \(F_{1}\) is the elastic force of its rubber sleeve; \(F_{2}\) is the force load; and \(F\) is the contraction force of the pneumatic muscle.

The elastic force of the pneumatic muscle rubber sleeve can be expressed by Eq. (4).

where \(A\) and \(E\) are the cross-sectional area and modulus of elasticity of the pneumatic muscle rubber sleeve, respectively.

When the pneumatic muscle was inflated to exert a contraction force, the length of the single fiber \(l\) could be assumed to remain constant in the contraction process, as the stiffness of the fiber layer was much greater than that of the inner rubber sleeve.

The function of the geometric parameters in the fiber layer can be expressed by Eqs. (5) and (6).

where L is the length of the pneumatic muscle, \(l\) is the length of the single fiber, \(n\) is the number of wraps around the fiber, \(D\) is the diameter of the pneumatic muscle, and \(\theta\) is the weave angle of the wound fiber.

Assuming that the volume inside the pneumatic muscle rubber sleeve did not change during actuation, it can be related with the cross-sectional area of the rubber sleeve as in Eq. (7).

Based on the fact that the work done by the constant pressure gas on the pneumatic muscle is equal to the external work done by the contraction of the pneumatic muscle in any small section, the contraction of the pneumatic muscle can be expressed by Eq. (8).

Substituting Eqs. (5) and (6) into Eq. (8), we get:

where \(p\) is the internal air pressure on the pneumatic muscle, and \(p_{0}\) is the standard atmospheric pressure.

In this study, pneumatic muscles of the same size were arranged on both sides of each rib to ensure the symmetrical output from the driving load.

The flexible section structure of a rib was equated to the structure of a single-joint mechanical arm in the control system based on its deformation characteristics. The bending deformation mode of the mid-arc line on the trailing edge of the rigid-flex hybrid wing rib is shown in Fig. 2. In order to construct a simulation model of the rib flexible section drive, various structural parameters should be determined. structural parameters include the rotational inertia of the structure based on its axis of rotation, and the mass and centre of mass of the structure. Those parameters could be directly measured by creating the 3D digital model of the structure (see Table 2). Finally, the creation of a mathematical model for structural rotational dynamics is completed.

In practice, the parameters and disturbances of a real physical model are often not precisely available. Hence, the modelling errors present in the parameters of the system model need to be taken into account. In order to obtain an accurate dynamical model, it was divided into a deterministic part and a modelling error part separately, also known as the nominal model of the real object. The dynamics of the rib flexible part was modeled by the Lagrangian method as in Eq. (10)23.

where M, C, G and K are the rotational inertia, variable bending damping, rotational moment due to gravity and rotational stiffness of the equivalent joint of the structure, respectively; \(\tau\) and \(\tau_{d}\) are the control moment and applied disturbance, respectively.

where \(E_{M}\), \(E_{C}\), \(E_{G}\) and \(E_{K}\) characterize the errors in the parameters of the model.

As a special robust nonlinear control method, the sliding mode control is used in a large number of applications in the field of robot or mechanical arm joint control. In this study, the sliding mode variable structure control method was used in combination with a nominal model of the system for controlling the drive based on the deformation characteristics of the designed flexible structure. The error developed in the modelling process of the structure was fully considered in the design process of the control rate.

In the controller design, the equivalent deflection angle of the variable bending drive control of the flexible structure was taken as the control quantity and feedback quantity of control system24,25. So, the error in angle tracking can be defined as in Eq. (15).

where \(q_{d} (t)\) is the signal of the ideal angle and \(q(t)\) is that of the actual angle.

The sliding surface function can be defined as in Eq. (16).

where \(\Lambda\) is the slope of the sliding surface, which determines the speed at which the control converges to the zero point of the sliding mode. It can be defined as in Eq. (17).

From Eq. (10), we obtain:

where

The controller is designed as in Eq. (20).

where \(\tau_{m}\) is the control rate based on the nominal model; \(\tau_{r}\) is the robust term to overcome the system modelling errors and external disturbances; and \(K_{p} > 0,K_{i} > 0\) are the proportional constant matrix and integral constant matrix, respectively.

Flexible wing rib drive control tests

Based on the structural optimization results, 7075Al-T6 alloy material was used for physical fabrication and variable bending capacity test.

The equivalent deflection angle of the structure of the rib compliant section, obtained by observing and calculating an internal air pressure of 396.18 kPa in the pneumatic muscle at a drive voltage of 6.5 V, was up to 15° as shown in Fig. 17.

In order to verify the variable bending capability of the rib flexible section structure, the coordinates of the marker points under the target deflection angle of the actual structure were fitted to obtain the variable bending configuration map of the actual structure, and then compared with the target variable bending configuration, as shown in Fig. 18. The error between the two structures was only 8%, which was mainly attributed to the difficulty in machining the variable bending beam in the rib model specimen and assembling the test system.

Finally, the control method was verified. In the test system, the direct test signal of the structural response was the root displacement of the lower airfoil measured by the laser rangefinder. At the same time, in order to ensure the structural safety of the test system and rib flexible section structure, and to minimize the influence of the limiter in the control system on the control results, the root displacement of the lower airfoil was set to 10.2 mm and the lower bending angle to 4°. The control parameters are the third set of control parameters obtained from the additional information, \(K_{p} = 2,K_{i} = 0.5,\Lambda = 20\).

The control results of the optimal simulation parameters are shown in Fig. 19, with a response time of 6.13 s, a steady-state error of 5.7%, and an overshoot of 4.9%. Figure 20 illustrates the deflection of the tip during the deformation of the compliant rib structure, while Table 3 presents the observed displacement values at the root of the lower wing surface and deflection angles.

Discussion and conclusion

In order to improve the flight performance and efficiency of aircrafts, a solution procedure is proposed by comprehensively considering various factors, such as variable amplitude, deformation continuity, and drive control.

A parametric geometric description method for wing camber configuration was established based on the camber line of the airfoil, corresponding to a target deflection of 30° at the trailing edge. Using the lift-to-drag ratio of the airfoil as the evaluation function, the optimal camber configurations with the best down-deflection angles were obtained for both rigid and flexible sections.

By performing computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, the aerodynamic characteristics, such as the lift coefficient and lift-to-drag ratio, of two airfoils were compared at different angles of attack for a 30° trailing edge deflection configuration. The obtained results showed that, within the range of angle of attack of -4° to 8°, the mixed rigid-flexible airfoil outperformed the traditional rigid deflection airfoil in terms of both lift coefficient and lift-to-drag ratio, with the advantage being more pronounced at lower angles of attack. This is because, at higher angles of attack, flow separation occurs at the trailing edge, leading to increased drag and reduced aerodynamic efficiency.

Under actual flight conditions, with the lift of the wing per unit span as the optimization objective, the optimal down-deflection angles for the two different trailing edge configurations were calculated for both low-speed cruise and landing conditions. In the low-speed cruise condition, the mixed rigid-flexible deflection wing needed only to deflect the flexible section by 8.7° to meet the target lift, while the traditional rigid deflection wing required the entire trailing edge to deflect by 7.3°. In the landing condition, the mixed rigid-flexible deflection wing needed to deflect the rigid section by 3.78° and the flexible section by 15°, achieving an overall equivalent deflection of 16.1° to meet the optimization target. Whereas, the traditional rigid deflection wing required a deflection of 29° for the entire trailing edge. Furthermore, CFD simulations were conducted to calculate flow field characteristics, whose results showed that the mixed rigid-flexible deflection wing had a greater advantage at large deflection angles. In the landing condition, its lift-to-drag ratio increased by 78% compared to that of the traditional rigid deflection wing. The calculations also revealed that the flow separation point was closer to the trailing edge, located at x/c = 0.8, and the vortex structure at the trailing edge was smaller, resulting in higher aerodynamic efficiency.

The 7075-T6 high-strength aluminum alloy commonly used in aerospace is employed as the design material. The topology of the wing rib structure is optimized based on load path analysis. A brief overview of the process of topology optimization for flexible structures is provided, and the final configuration of the flexible structure in the morphing wing is presented.

Subsequently, considering the modeling errors of the flexible wing rib structure dynamics and practical application scenarios of the mixed rigid-flexible trailing edge bending wing, the bending control of the wing rib structure was studied using a sliding mode variable structure control method based on a nominal model. Firstly, a mathematical model of the pneumatic muscle-driven output was established. Secondly, the wing rib structure was approximated as a single-degree-of-freedom robotic arm system, and then its dynamics were modeled. Thirdly, the PI sliding mode control method was employed to model the drive control, and the controller parameters were adjusted.

Finally, 7075-T6 aerospace-grade aluminum was used to manufacture the wing ribs, and a wing rib deformation control test system was constructed. Firstly, the deformation capability of the compliant deformation structure was tested, where the deformed outer contour curve of the wing ribs closely matched with the target deformation curve, with a maximum error of only 8%. Subsequently, upon using the PI variable structure control algorithm, the flexible section was able to quickly and stably deform to the target position. The actual adjustment time was only 6.13 s, with a steady-state error of 5.7% and 4.9% overshoot, demonstrating that the proposed control method was reasonable and effective.

Additional information

The main content of the additional information is the simulation of the PI control system and the acquisition of optimal control parameters.

The flexible structure variable bending controller was built on the Simulink simulation platform, as shown in Fig. 21.

In the sliding mode variable structure control method based on the nominal model, proportionality coefficient \(K_{p}\), integration coefficient \(K_{i}\) and the slope of sliding surface parameter \(\Lambda\) in the controller were adjusted by taking four different sets of adjustment parameters, as listed in Table 4. At the same time, the response curves for different control parameters were plotted, as shown in Fig. 22.

The simulation results indicate that when using the control parameters from sim3, the system exhibits the shortest adjustment time, along with the smallest steady-state error and overshoot. Therefore, these parameters were adopted in the control experiment.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript .

Abbreviations

- UAV:

-

Unmanned aerial vehicle

- PI:

-

Proportional integral

- CL :

-

Lift coefficient

- CD :

-

Drag coefficient

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- SST:

-

Shear stress transport

- AOA:

-

Angle of attack

References

Zhou, W. et al. Structure-actuator integrated design of piezo-actuated composite plate wing for active shape control. J. Aerosp. Eng. 34, 04021012 (2021).

Umes, J., Nguyen, N. et al. A mission adaptive variable camber flap control system to optimize high lift and cruise lift to drag ratios of future N+3 transport aircraft. In: Proceedings of AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting Including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition. (AIAA, 2013).

Lu, K. J. & Kota, S. Parameterization strategy for optimization of shape morphing compliant mechanisms using load path representation. In Proceedings of ASME 2003 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, 693–702 (ASME, 2003).

Miller, E. J., Cruz, J., Kota, S. et al. Evaluation of the hinge moment and normal force aerodynamic loads from a seamless adaptive compliant trailing edge flap in flight. In Proceedings of AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, 2016–0038 (AIAA, 2016).

Kota, S., Flick, P. & Collier, F. S. Flight testing of flexfoil TM adaptive compliant trailing edge. In Proceedings of AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, 2016–0036. (AIAA, 2016).

Janett, B. E., Gershenfeld, N., Swei, S., Cramer, N. & Cheung, K. Elastic shape morphing of ultra-light structures by programmable assembly. US. Patent US20200283121A1[P] (2020).

Sinapius, M. et al. DLR’s morphing wing activities within the European network. Proc. IUTAM 10, 416–426 (2014).

Woods, B. K. S. & Friwell, M. I. Preliminary investigation of a fishbone active camber concept. In: Proceedings of ASME Conference on Smart Materials (2012).

Christine, F. Inspired by Fish By Christine Fisher. https://aerospaceamerica.aiaa.org/department/inspired-by-fish/ (2020).

Dimino, I., Moens, F., Pecora, R. et al. Morphing wing technologies within the Airgreen 2 project. In Proceedings of AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Multidisciplinary design and optimization of trailing edge of morphing wing. J. Nanjing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. (in Chinese) 53(3), 415–424 (2021).

Snow S. A. & Hunsaker, D. F. Design and performance of a 3D-printed morphing aircraft. In Aircraft Design, 1060 (2021).

Mkhoyan, T., Thakrar, N. R., Breuker, R et al. Design of a smart morphing wing using integrated and distributed trailing edge camber morphing. In ASME 2020 Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems (2020).

Jenett, B. et al. Digital morphing wing: Active wing shaping concept using composite lattice-based cellular structures. Soft Rob. 4(1), 33–48 (2017).

Festo AG & Co. KG. Technical Documentation: Pneumatic Muscle DMSP-20. Version 3.1, Festo Corporation (2023). www.festo.com/documentation/dmsp-20.

Utkin, V. I. Sliding Modes in Control and Optimization (Springer, 1977).

Lin, W. & Chai, T. Neural network-based sliding mode control for robotic manipulators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 56(9), 3296–3304 (2010).

Edwards, C. & Spurgeon, S. K. Sliding Mode Control: Theory and Applications (CRC Press, 1998).

Zhang, J. et al. Aeroelastic model and analysis of an active camber morphing wing. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 111, 106534 (2021).

Sheldahl, R. E. & Klimas, P. C. Aerodynamic Characteristics of Seven Symmetrical Airfoil Sections Through 180-Degree Angle of Attack for Use in Aerodynamic Analysis of Vertical Axis Wind Turbines. SAND-80-2114, Sandia National Laboratories (1981)

Zhao, S. et al. Numerical and experimental study of a flexible trailing edge driving by pneumatic muscle actuators. Actuators 10(7), 142 (2021).

Ficola, A. & Cava, M. L. A. Sliding mode controller for a two-joint robot with an elastic link. Math. Comput. Simul. 41(5/6), 559–569 (1996).

Young, K. D., Utkin, V. I. & Ozguner, U. A control engineer’s guide to sliding mode control. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 7(3), 328–342 (1999).

Poonsong, P. Design and Analysis of a Multi-Section Variable Camber Wing (University of Maryland, 2004).

Lim, S. M. et al. Design and demonstration of a biomimetic wing section using a lightweight piezo-composite actuator (LIPCA). Smart Mater. Struct. 14(4), 496 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This paper was completed with the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11872312).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xin Tao provided a method for aerodynamic optimization and completed relevant numerical calculations. Li Bin conceived the control method for the driver, and Xin Tao completed the design of the controller. Xin Tao and Li Bin jointly designed and completed the control experiment.Xin Tao wrote the main manuscript text.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xin, T., Li, B. Research on aerodynamic characteristics and control method of rigid-flexible variable camber wing. Sci Rep 15, 25904 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08792-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08792-8