Abstract

Coronary atherosclerotic heart disease is one of the most common diseases, and health-promoting behaviors such as diet, exercise, and lifestyle habits are essential to improve the prognosis of patients with coronary heart disease. This study aimed to assess the health-promoting lifestyle status of patients following percutaneous coronary intervention and to analyse its influencing factors. A survey was conducted among 300 patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention. Data were collected using a general information questionnaire and the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile. Multiple linear regression analysis identified ethnicity, monthly household income, and the presence of comorbidities as significant factors influencing the health-promoting lifestyle of these patients. The average scores for the health-promoting lifestyle post-intervention were (162.91 ± 12.24), which are considered favourable. The components of the health-promoting lifestyle were ranked from highest to lowest based on subscale scores: self-actualisation, interpersonal support, stress management, nutrition, health responsibility, and exercise. Healthcare professionals should tailor health education programs for patients based on their ethnic backgrounds, income levels, and whether they have comorbid conditions. This targeted approach can effectively enhance their health responsibility and improve their overall health-promoting lifestyle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of global mortality1. Estimates indicate that in 2023, there are approximately 330 million cases of the disease in China2. Additionally, both morbidity and mortality rates from this disease are rising in the country. Contributing factors include unhealthy lifestyle choices such as poor diet, lack of exercise, smoking, and alcohol consumption, along with increasing metabolic risks and a rapidly ageing population. Reports from 2021 show that CVD is the leading cause of death in China, accounting for 48.98% of deaths in rural areas and 47.35% in urban areas2.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) remains one of the most common and lethal diseases globally3 and a leading cause of disability, significantly burdening the healthcare system4. The Global Burden of Disease 2019 reported that CHD causes 9.14 million deaths worldwide, accounting for 49.2% of all cardiovascular deaths and 16.3% of all deaths5. A health-promoting lifestyle can motivate individuals’ aspiration for a healthy body and plays a facilitating role in curbing the unhealthy habits of patients with coronary heart disease6. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) uses a cardiac catheter to open narrowed or blocked coronary arteries, improving myocardial blood circulation. With its less invasive approach, reduced operation time, and quicker recovery, PCI has become a primary clinical procedure for CHD patients7.

Lifestyle is a crucial factor in the development of CHD8, with unhealthy habits playing a key role in poor outcomes, recurrence, and rehospitalisation after treatment. Health-promoting behaviours (HPBs) are positive actions individuals take across various dimensions to enhance their health status9. These behaviours include non-smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, engaging in regular physical activity, and adopting healthy dietary patterns, which are pivotal in current strategies to improve cardiovascular health in the general population10. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle significantly reduces the risk of clinical coronary events and lessens the subclinical burden of coronary artery disease across all genetic risk categories11. The Healthy China Initiative (2019–2030) emphasises the need for extensive research on major lifestyle risk factors for CVD in China to aid in early diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation12, highlighting the importance of a health-promoting lifestyle in managing and reversing chronic diseases. For patients post-PCI, adopting HPBs is crucial for improving their physical and mental health, quality of life, and prognosis.

Although previous studies have explored the health-promoting lifestyle of post-PCI patients, the relevant evidence from different regions, diverse populations, and various dietary habits remains limited. These factors may have an impact on the health-promoting behaviors of post-PCI patients.

Therefore, this study aims to assess the HPBs of post-PCI patients and analyse the factors influencing these behaviours, thus helping patients understand and potentially improve their lifestyle. This awareness could motivate them to adopt healthier habits. Additionally, the study findings may inform the development of intervention plans by healthcare professionals.

Participants and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study was reviewed and approved by the hospital ethics committee (K202410-20). Throughout the entire research process, the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki were adhered to. All participants provided written informed consent, the questionnaires were uniformly stored by the researchers, and the research methods strictly complied with relevant guidelines.

Participants and procedure

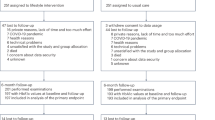

The study adopted the convenience sampling method to recruit patients who underwent PCI at a Class A tertiary hospital from April 2024 to July 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who met the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Chinese Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (2016)13, underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, and were successfully treated; (2) aged 18 years or older; have normal comprehension ability and be able to complete the questionnaire independently or with the help of the researcher; and (3) provided informed consent and voluntarily participated in this study. The exclusion criteria included: (1) patients with cognitive and mental disorders or functional impairments in vision or hearing; (2) patients with functional impairments in vital organs or serious chronic comorbidities; and (3) patients with language dysfunctions that impede effective communication.

Methods

Instruments

General information questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed by the researcher to collect the following information: (1) General demographic data, including each patient’s admission number, sex, age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, monthly household income, employment status, smoking status, and alcohol consumption; (2) Disease-related information, such as each patient’s height, weight, overweight status, whether it was their first diagnosis of CHD, the time of diagnosis, duration of the disease, presence of comorbidities, and the grading of their cardiac function.

Health-promoting lifestyle scale

The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile-II (HPLP-II), developed by Walker et al14., was utilised to assess the level of health-promoting behaviours (HPBs) of the participants. It has been translated from English to Chinese with cultural validations. It has a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.91)15. The Chinese version HPLP-II consists of the same 52 items, covering six dimensions: health responsibility (with 9 items, such as reporting my abnormal signs or symptoms to healthcare providers, watching TV programs about promoting health, and asking questions when having difficulties in understanding the suggestions from healthcare providers, etc.), exercise (with 8 items, such as doing exercises according to the planned program, doing stretching exercises at least three times a week, and reaching the target heart rate during exercise, etc.), Nutrition (with 9 items, such as choosing a diet low in fat, saturated fat and cholesterol, limiting the intake of sugar and sugary foods, having breakfast, and reading the labels on food packages to confirm the nutritional content, fat and sodium levels, etc.), self-actualisation (with 9 items, such as feeling that I am growing and changing in a positive way, believing that my life has a purpose, and being full of hope for the future, etc.), interpersonal support (with 9 items, such as discussing my difficulties and concerns with relatives and friends, easily praising others for their achievements, and spending time with good friends), and stress management (with 8 items, such as having sufficient sleep, taking time to relax myself every day, and thinking of some pleasant things before going to bed, etc.). In the current study, the scale adopted the Likert 4-point scoring method, ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The total score ranges from 52 to 208 points. The scores of the Physical Activity and Stress Management dimensions are between 8 and 32, while those of the other four dimensions are between 9 and 36.It uses a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 52 to 208, where higher scores indicate higher levels of HPBs. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.95, with dimensional values ranging from 0.70 to 0.86.

Data collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire method. The researcher explained the study’s purpose and significance to the participants and obtained their informed consent before administering the questionnaire. The researcher asked the 52 items in the HPLP-II to the participants one by one. During the questioning process, the researcher did not interrupt the participants casually, listened carefully to their statements, and refrained from giving any hints or guidance. The researcher assigned scores according to the participants’ answers to avoid errors that might arise if the participants filled out the questionnaire by themselves, thus completing the questionnaire administration.

The sample size was calculated to be 5–10 times the number of independent variables in the questionnaire.In this study, the general information included 20 variables, and the HPLP-II had a total of 6 dimensions, resulting in a total of 26 independent variables. Therefore, the required sample size was 130 to 260, accounting for a potential 10% attrition rate the sample size was adjusted to 143 to 286. Finally, the sample size was expanded to 300 cases.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered twice into Excel to create a database. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0. Descriptive statistics summarised the general information, while measurement data were presented as mean and standard deviation (\({\overline{\text{x}}}\) ± s) and enumeration data as numbers and percentages (%). Two independent samples t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and multiple linear regression were used to analyse factors influencing the health-promoting lifestyle, with a significance threshold set at P = 0.05.

Results

Levels of health-promoting lifestyle in post-PCI patients

The distribution of health-promoting lifestyle levels among post-PCI patients is illustrated in Fig. 1. The overall health-promoting lifestyle score for post-PCI patients was (163.10 ± 12.23). The scores for the six dimensions, in descending order, were self-actualisation, interpersonal support, stress management, nutrition, health responsibility, and exercise, as detailed in Table 1.

One-way analysis of variance of the health-promoting lifestyle in post-PCI patients

Demographic and disease-related information was gathered through a general information questionnaire, which included data on sex, age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, monthly household income, employment status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, overweight status, initial diagnosis of CHD, duration of the disease, the presence of comorbidities, and cardiac function grading, as summarised in Table 2. The analysis of health-promoting lifestyle scores among post-PCI patients showed statistically significant differences when grouped by ethnicity, sex, monthly household income, and the presence of comorbidities (P < 0.05).

Multiple linear regression analyses of factors influencing health-promoting lifestyles in post-PCI patients

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed with the total health-promoting lifestyle score as the dependent variable. The independent variables included those that were statistically significant in the one-way analysis of variance: ethnicity, monthly household income, and the presence of comorbidities, detailed in Table 3. A scatter plot illustrating these relationships, based on the regression equation, is presented in Fig. 2. The results indicate that ethnicity, monthly household income, and the presence of comorbidities significantly influence the health-promoting lifestyle of post-PCI patients (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The health-promoting lifestyle of post-PCI patients is at a favourable level

The current study found that the overall health-promoting lifestyle score of post-PCI patients can be classified as favourable. The scores were relatively high in the dimensions of self-actualisation, interpersonal support, and stress management yet lower in nutrition, health responsibility, and exercise.

Among these six dimensions, self-actualisation scored the highest, supporting the findings of Juan Chen16,17. High levels of self-actualisation and interpersonal support were noted, while scores for health responsibility and exercise were lower, aligning generally with the research of other scholars18,19,20,21. The high scoring in self-actualisation may be influenced by the age of participants, as most were over 50 years old. This age group often includes individuals approaching or in retirement who possess extensive life experience and broad social connections, potentially enhancing their ability to foster good interpersonal relationships. The higher scores in interpersonal support and stress management could be linked to employment status and age. Nearly half of the study participants were retired, and almost 90% were over 50 years old. Being in a stage of life with potentially less work and life stress may enable better emotional, informational, material, or operational support and assistance.

The level of the health responsibility dimension is relatively low, which is consistent with the research findings of Jinfeng Liu17. As for the relatively low level of the nutrition dimension, it is slightly different from the research results of other scholars22,23,24, lower scores in the nutrition and health responsibility dimensions could be attributed to regional and ethnic dietary preferences, with a significant portion of participants having lower monthly household incomes and only upper secondary education or below. In terms of health responsibility, low-income individuals might be deterred by the high costs of medical treatment, resulting in poor adherence to medication and follow-up care after symptom relief post-PCI. Their diets tend to be carbohydrate-heavy, overlooking the importance of nutritional balance. Conversely, individuals with higher education levels often show greater concern for their health and nutrition, are better able to evaluate health information, and more effectively absorb and apply health-promoting knowledge, thereby adjusting their behaviours to enhance their health.

The lowest score in the exercise dimension aligns with the findings of other researchers25,26. Possible reasons include young patients being too occupied with work to find time for exercise or assuming they are in good physical condition and thus neglecting physical activity. As individuals age, a decline in bodily functions or the presence of comorbidities may also reduce their exercise levels. Greater physical activity is related to improved health outcomes in people living with coronary heart disease. Physical activity is associated with a decreased risk of CVD mortality. It also reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease progression and lowers blood pressure27. Habitual physical activity is associated with improved outcomes in individuals with CVD. Shifting from a sedentary lifestyle to engaging in at least low-intensity physical activities can improve metabolic and cardiovascular health28. This underscores the importance of health education during hospitalisation. Educational topics could include the nutritional benefits of low-salt and low-fat diets, as well as the advantages of endurance training, such as walking, jogging, and Tai Chi.

Ethnicity, monthly household income, and comorbidities are major influencing factors in the health-promoting lifestyle

Research indicates that the Kazakh population has a suboptimal intake of vegetables and fruits and a diet characterised by high salt, milk tea, high fat, cured and smoked meats, reliance on animal fats, and a low intake of fish29. The Mongolian population scored highest in exercise and lowest in stress management, likely reflecting the age and occupational characteristics of the participants30. Ethnic minorities in northern China, influenced by their environment and traditional practices, consume more alcohol and fat31. In Xinjiang, the intake of high-fat foods is notably high32, and distinct ethnic dietary habits and lifestyles may impact cardiovascular health and behaviours. Given these differences, healthcare professionals should tailor their communication strategies to address dietary health effectively.

Patients with monthly household incomes below 1,000 Yuan exhibit lower health-promoting lifestyle scores compared to those earning between 3,001 to 5,000 Yuan and over 5,001 Yuan. This correlation supports previous studies33,34,35, suggesting that financial status significantly affects access to medical care and medication. Patients with higher incomes tend to be more committed to their health, face less stress over medical costs, and adhere better to follow-up instructions. They also have more resources and time for exercise and maintaining a balanced diet. Economic conditions not only affect the access to medical resources but also indirectly promote healthy behaviors by reducing psychological stress. Since CHD requires long-term management and consistent adherence to medication and check-ups, the financial strain can be substantial for low-income patients. Healthcare professionals should vary their health education approaches based on financial status, emphasising the importance of medication adherence, regular check-ups, a balanced diet, and appropriate exercise for those with lower incomes.

Patients without comorbidities typically exhibit lower health-promoting lifestyle scores than those with comorbid conditions, confirming observations by Qiao He34. Having one or more comorbidities may heighten health responsibility, leading to greater concern and knowledge about health, which contributes to a healthier lifestyle. Therefore, healthcare professionals should educate CHD patients without comorbidities about potential complications and instruct them to monitor their blood pressure and glucose levels regularly after discharge, ensuring they understand when to seek medical help in a timely manner.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study that are worthy of consideration. Firstly, this study was conducted with patients from only one hospital and involved a limited sample size, which restricts the generalizability of the results. Future studies will employ qualitative interview methods to deepen the understanding of the factors influencing the health behaviours of post-PCI patients and to inform the development of effective intervention plans. Secondly, when using cross-sectional studies to analyze the factors influencing the health-promoting lifestyle, interventional studies or longitudinal studies are still needed to determine the causal relationships among variables.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the health-promoting lifestyle of post-PCI patients and analysed potential influencing factors. The findings indicate that the health-promoting lifestyle of post-PCI patients is generally favourable, with ethnicity, monthly household income, and comorbidities identified as key influencing factors. Consequently, healthcare professionals should develop tailored health education strategies based on diverse populations, income levels, and the presence or absence of comorbidities. During the nursing intervention process, the level of the health-promoting lifestyle of patients after PCI should be comprehensively evaluated, and health interventions for those with a low average monthly household income and those suffering from comorbidities should be strengthened. Such strategies are likely to help enhance patients’ health responsibility, assist post-PCI patients in establishing and maintaining a healthy lifestyle, and further improve their health-promoting lifestyle after PCI.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu S, Li Y, Zeng X, Wang H, Yin P, Wang L, et al. Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases in China, 1990–2016: Findings From the 2016 Global Burden ofDisease Study. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4(4):342–52. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6484795/

Summary of the China Cardiovascular Health and Disease Report 2023[J]. Chinese Circulation Journal. 39(07):625–60. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2024.07.001 (2024)

Expert consensus on cardiac rehabilitation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Chinese Circulation Journal. 35(01):4–15. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2020.01.002

Chen, Y., Lin, F. F. & Marshall, A. P. Patient and family perceptions and experiences of same-day discharge following percutaneous coronary intervention and those kept overnight. Intensive Crit. Care Nur 62, 102947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102947 (2021).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. American heart association strategic planning task force and statistics committee defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic ImpactGoal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 121(4), 586–613. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.109.192703 (2010).

Hypertension Prevention and Control Association of Beijing, Diabetes Prevention and Control Association of Beijing, Research Association of Prevention, Treatment and Health Education of Chronic Diseases in Beijing, et al. Practical Guidelines for the Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Diseases at the Grassroots Level 2020 [J]. Chinese Journal of the Frontiers of Medical Science (Electronic Version), 12(8): 1, 1–73.) https://doi.org/10.12037/YXQY.2020.08-01. (2020).

Hu, S., Pan, X. & Chang, Q. Expert consensus on interventional diagnosis and treatment of common cardiovascular diseases via surgical route. Chine. Circu. J. 32(02), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2024.07.001 (2017).

Malakar, A. K. et al. A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. J. Cell Physiol. 234(10), 16812–16823. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.28350 (2019).

Noble, H. & Barrett, D. Health promotion. Evid. Based Nurs. 22(1), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2018-103031 (2019).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76(25), 2982–3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 (2020).

Khera, A. V. et al. Genetic Risk, Adherence to a Healthy Lifestyle, and Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(24), 2349–2358. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1605086 (2016).

Hu, S. Implementing Healthy China Initiative and promoting health awareness. Chine. Circul. J. 34(9), 844–845. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.09.002 (2019).

Interventional Cardiology Group of the Chinese Medical Association Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Thrombosis Prevention and Treatment Professional Committee of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association Cardiovascular Physicians Branch, Editorial Board of the Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary intervention in China (2016). Chinese Journal of Cardiology. 44(5):382–400. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2016.05.006 (2016).

Walker, S. N., Sechrist, K. R. & Pender, N. J. The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs. Res. 36(2), 76–81 (1987).

Lee, R. L. & Loke, A. J. Health-promoting behaviors and psychosocial well-being of university students in Hong Kong. Public Health Nurs. 22(3), 209–220 (2005).

Chen, J. et al. Analysis of health behaviours and their influencing factors in young stroke patients. Chine. J. Health Statistics. 36(05), 722–723 (2019).

Jinfeng, L. & Banghui, H. Health-promoting Lifestyle and Influencing Factors of Retired Faculty and Staff in Guiyang City. Chin. J. Gerontol. 40(19), 4220–4223. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2020.19.057 (2020).

Cheng, J. et al. A study on the status and influencing factors of the health-promoting lifestyle of residents aged 18–65 in China. Chine. Health Ser. Manag. 39(01), 76–80 (2022).

Li, J. & Tao, R. A survey study on the health-promoting lifestyle of students in a medical school. J. Qiqihar Med. Univ. 41(12), 1514–1516. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-1256.2020.12.023 (2020).

Cai, W. Status assessment of the health-promoting lifestyle among medical students. China Medical University. https://doi.org/10.27652/d.cnki.gzyku.2020.000662 (2020).

Tianqi, Y. Analysis of the current status of health-promoting behaviors and influencing factors in patients with coronary heart disease. Chine. J. Modern Nursing 29(6), 775–780. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn115682-20220712-03391 (2023).

Yinuo, W. et al. Correlation between e-health literacy and health-promoting lifestyle of community-dwelling elderly people. J. Nurs. Sci. 37(10), 100–102. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2022.10.100 (2022).

Yang, T. et al. Correlation analysis of e-health literacy with health-promoting lifestyle and emotion regulation among nursing students. Chine. J. Health Education. 40(9), 835–838 (2024).

Samiei Siboni, F., Alimoradi, Z. & Atashi, V. Health-promoting lifestyle: A considerable contributing factor to quality of life in patients with hypertension. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 15(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827618803853 (2018).

Zhou, C. et al. Influence of health promoting lifestyle on health management intentions and behaviors among Chinese residents under the integrated healthcare system. PLoS ONE 17(1), e0263004. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263004 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Analysis of status quo and influencing factors for health-promoting lifestyle in the rural populace with high risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 23(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03129-7 (2023).

Bull, F. C. et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J. Sports Med. 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 (2020).

Virani, S. S. et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease: A report of the american heart association/american college of cardiology joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 148(9), e9–e119. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168 (2023).

Yuan, Y. et al. Analysis of risk factors and construction of a early warning model for high-risk cardiovascular disease populations among Kazakh nomads in the Nanshan Pasture Xinjiang. Hebei Med. J. 46(05), 778–782. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-7386.2024.05.031 (2024).

Lu, H. et al. Study on the correlation between health beliefs and health behaviours among the prehypertensive Mongolian population. J. Mudanjiang Medical College. 42(2), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.13799/j.cnki.mdjyxyxb.2021.02.021 (2021).

Fang, J. Progress of research on risk factor aggregation in coronary heart disease. Chin. Nurs. Res. 37(23), 4241–4246 (2023).

Lu, W. H. et al. Correlation between Occupational Stress and Coronary Heart Disease in Northwestern China: A Case Study of Xinjiang. Biomed Res. Int. 1, 8127873. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8127873 (2021).

Chen, A. & Zhang, L. Study on the health-promoting lifestyle and influencing factors among patients with chronic diseases in old urban areas of Guangzhou. Chine. General Practice. 23(25), 3241–3246 (2020).

He, Q. et al. Research progress on the influencing factors of the health-promoting lifestyle among patients with chronic diseases. Chine. J. Modern Nursing. 23(29), 3689–3692. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2907.2017.29.001 (2017).

Xiao, L., Wang, P., Fang, Q. & Zhao, Q. Health-promoting lifestyle in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean Circ. J. 48(6), 507–515. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2017.0312 (2018).

Funding

Special Nursing Project of the State Key Laboratory of Pathogenesis, Prevention and Treatment of High Incidence Diseases in Central Asia, a provincial-ministry joint project (SKL-HIDCA-2023-HL4), Xinjiang Key Laboratory of Medical Animal Model Research, and the Project of Cultivation of Excellence Talents and Innovative Teams of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (cxtd202414).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C:investigation,formal analysis,writing-original draft; Y:conceptualization, investigation,formal analysis; Ma Jing:investigation, resources; Ma Lina:investigation,formal analysis; G:formal analysis,writing-review& editing; P:investigation,formal analysis; Z:conceptualization,methodology, writing-review & editing,resources, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participation was entirely voluntary, and anonymity and confidentiality were assured by ethical rules for research on humans. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. Voluntary consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and consent to submission.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Z., Yan, P., Ma, J. et al. Factors influencing health-promoting lifestyles in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: A cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 23646 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08996-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08996-y