Abstract

Plantations in degraded forest areas in arid and semi-arid regions play a vital role in restoring ecosystems, controlling erosion, and supporting local livelihoods. However, little is known about how exotic and native tree species influence nutrient dynamics in soil and foliage, particularly regarding nutrient retranslocation. This study evaluated seasonal variation in leaf nutrient concentrations and nutrient retranslocation patterns over a 6-month period (early April to late September) in 30-year-old plantations of two exotic needleleaf species (Cupressus arizonica, Pinus eldarica) and two indigenous broadleaf species (Amygdalus scoparia, Quercus brantii). The findings revealed significant differences among species groups. Broadleaf species generally exhibited higher concentrations of leaf nutrients (such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and magnesium (Mg) and lower C: N ratios than needleleaf species. Seasonal effects were evident, with leaf nutrient content generally higher in spring than in summer. The order of nutrient retranslocation was as follows: Ca < C < K < Mg < N < P. Further analysis using principal components highlighted the differences between broadleaf and needleleaf plantations in terms of soil and leaf nutrient status. These findings suggest that, due to its native status and greater contribution to soil fertility, Q. brantii is a suitable choice for reforestation in similarly degraded environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Zagros oak forests in western Iran are crucial for protecting water and soil, as well as preventing desertification1. Theses forests are located in arid and semi-arid climate. Therefore, any reduction in their area or quality can have serious environmental and social consequences. Unfortunately, the forests in this region have been degraded by livestock grazing, land use change, fire, and human activity, particularly around towns and villages2. Plantations play an important role in restoring degraded ecosystems3,4. However, there is still a gap in our knowledge of how exotic and indigenous tree species in plantations affect soil and leaf nutrients, as well as nutrient retranslocation. This information is crucial for selecting suitable species, understanding their ecological impact, and ensuring the success of forest restoration efforts. As the main photosynthetic organs of most plants, leaves play a central role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem function. Their elemental composition reflects a plant’s nutritional status, the availability of nutrients in the soil, and species-specific resource allocation strategies. As such, leaf nutrient profiles can serve as valuable indicators of ecosystem productivity and health5. Essential macronutrients such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) are vital for key physiological processes, including photosynthesis, cellular respiration, enzyme activation, protein synthesis, and stomatal regulation6. Chemical element concentration and stoichiometric ratios are important functional traits in plant ecology, because they can explain ecosystem function and plant evolutionary history7. Assessing these traits across seasons or among different woody species enhances our understanding of plant responses and adaptations to varying environmental conditions.

Nutrient retranslocation is a fundamental physiological mechanism that enables plants to conserve essential nutrients by retrieving them from senescing organs, particularly leaves. High retranslocation efficiency enables plants to decrease their dependence on soil nutrient availability, particularly in environments with limited nutrients. This process directly impacts the quality of litter, the decomposition of soil organic matter, and the overall cycling of nutrients within ecosystems8,9. Literature reviews have shown that needleleaf species typically exhibit longer leaf lifespans, lower leaf nutrient concentrations (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus), slower growth rates, and predominant occurrence in nutrient-limited ecosystems. As a result, their higher nutrient retranslocation efficiency is considered an adaptive conservation strategy, distinguishing them from deciduous broadleaf species. This distinction also helps to explain how broadleaf and needleleaf species differ ecologically in terms of their nutrient acquisition and survival strategies across diverse soil conditions10,11,12. Previous studies have also indicated that shrub species generally exhibit higher nutrient uptake and retranslocation rates, such as for nitrogen and phosphorus, compared to trees. This difference is often attributed to their smaller, shorter-lived leaves and their need to optimize nutrient use in resource-limited environments10,11,13. These findings emphasize that the efficiency of nutrient retranslocation varies considerably among plant species and can be influenced by environmental nutrient availability, plant physiological traits, and resource allocation strategies at different spatial scales and in different ecosystems14,15. The relationship between a plant’s nutritional condition and the composition of the soil it grows in is inherently complex and bidirectional. In general, most terrestrial plants acquire most of the mineral nutrients required for growth and reproduction from their soil. Consequently, plant nutrient concentrations should reflect the soil’s nutrient status to at least some extent16. However, this relationship can be significantly altered by species-specific nutritional strategies, such as mechanisms of nutrient retranslocation and return to the soil. These strategies play a critical role in shaping soil nutrient dynamics17.

Seasonal fluctuations are among the key factors that influence the chemical composition of leaves and soil. Therefore, plants must adjust their physiological and photosynthetic metabolisms seasonally and interannually to adapt to these changes. Several studies have thoroughly examined seasonal variations in functional leaf traits18. However, the mechanisms that regulate nutrient stoichiometry seasonally, especially in arid and semi-arid regions, are not well understood. Different studies have demonstrated that the availability and mobility of essential soil nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, as well as soil pH and electrical conductivity, are highly sensitive to seasonal variation19. Therefore, investigating the concurrent spatial and seasonal dynamics of nutrients in soil and foliage is a valuable approach for assessing ecosystem functioning and ecological status. These analyses can improve our understanding of biogeochemical cycling, ecosystem productivity, and species-specific nutrient acquisition strategies.

Previous studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the relative influence of species identity versus seasonal variation on leaf nutrient concentrations. For instance, some research has highlighted the significant impact of seasonal changes on nutrient availability in both soil and foliage, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions characterized by pronounced environmental fluctuations (e.g.18,19). In contrast, other studies have emphasized the dominant role of species-specific traits in nutrient uptake and retranslocation capacities, indicating that even in the absence of seasonal variation, marked interspecific differences in leaf nutrient profiles can be observed (e.g.7,10,11,13). Despite these insights, there remains a lack of comprehensive understanding regarding the primary drivers of leaf nutrient dynamics in our study region—an ecologically sensitive, dry to semi-arid Mediterranean ecosystem. Consequently, the hypotheses of this study were formulated to address this knowledge gap by evaluating the relative contributions of species identity and seasonal variation in shaping leaf nutrient patterns. Such an assessment is essential for improving our understanding of nutrient cycling processes and informing effective forest management and restoration strategies in degraded landscapes. The specific hypotheses of this research are as follows:

-

1.

Tree species is the main driver of leaf nutrient rather than seasonal variation.

-

2.

Leaf nutrient concentrations are higher in Indigenous species than in exotic species.

-

3.

The relationship between soil and leaf nutrient concentrations varies across seasons and among different tree species.

Materials and methods

Description of the research area

The study site is situated close to the Ilam County, western Iran (46° 19′ to 46° 21′ E longitude and 33° 37′ to 33° 38′ N latitude). There are no native needleleaf in these forests. Quercus brantii is the dominant native species in this semi-arid forest ecosystem. This species sometimes occurs in mixtures with Pistacia spp and Amygdalus spp. Historically, and especially in recent decades, these forests have been destroyed because people depend on them for their livelihoods, for firewood and to develop farmland. These disturbances, combined with natural factors, have caused most of these forests to become a coppice forest stands20,21,22 and, in many cases, the forest has been completely degraded. About 30 years ago, afforestation was carried out in the degraded and opened forest areas with some exotic needleleaf (Cupressus arizonica Greene and Pinus eldarica Medw) and indigenous broadleaf woody species (Amygdalus scoparia and Quercus brantii). The studied stands are positioned close to each other. These forests also occur with similar physiographic status (e.g. slope < 30% with mean altitude of 1350 m asl).

The mean annual temperature and precipitation are 17 °C and 590.4 mm, respectively.According to the De Martonne method, the research area has a semi-arid climate23. The predominant soil types in this region are calcareous and consist of shallow soils with a sandy clay loam texture24.

Experimental design

Leaf sampling and laboratory analysis

Leaf and soil nutrient sampling was carried out on four tree species, both exotic and indigenous, including Pinus eldarica Medw. and Cupressus arizonica Greene (exotic), as well as Quercus brantii Lindl. and Amygdalus scoparia (indigenous). For each species, three replicates (one individual from each of three stands) were selected in early spring (April) and late summer (September) 2020, resulting in a total of 4 species × 2 seasons × 3 replicates25. For each season, leaves were collected from cardinal four directions around the upper third of the tree crown26,27. Leaves from each tree were collected and combined separately by season, resulting in one composite spring sample and one composite summer sample per tree28.

To eliminate dust and other adhering particles, the sampled leaves were carefully rinsed with distilled water and subsequently dried in an oven at a temperature of 65 °C for a duration of 24 hours29. Following the drying process, the samples were separated into two parts. One of them was ground and used for the measurement of total carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) with the CHNSO analyzer (COSTECH-4010). The remainder of the sample was used to measure calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K), by the dry digestion method. Ash dissolved in 20 mL HCl (1 N), filtered through Whatman 42 filter paper, and the volume adjusted to 100 mL30. The measurement of phosphorus (P) was carried out by means of spectrophotometry. Finally, the content of other nutrients was determined by atomic absorption (Analytik Jena-Nov AA 400P, Jena, Germany).

Soil sampling and laboratory analysis

Soil samples were randomly collected under the canopies of individual trees in the study plantations. Sampling was conducted in the spring and summer of 2020 for each plantation. Initially, three random locations were identified within each plantation. Then, three soil samples were randomly collected at a depth of 20 cm from each of the locations to form a composite sample for soil analysis. Following the soil sampling process, the samples were air-dried and processed through a 2 mm sieve to facilitate analysis of their physical and chemical attributes. Soil texture was evaluated through the hydrometer aproach31. Furthermore, the soil water content (WC) measured using the weight technique, which compares the mass of water-saturated soil to that of soil dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 hours32. A total of 72 undisturbed soil cores were collected for bulk density (BD) determination33. Soil organic carbon (OC) and total nitrogen (N) determined by dichromate oxidation and titration34 and the Kjeldahl analysis35 respectively. The assay of lime (CaCO3) was conducted using the reverse titration approach36. Available potassium (K) was measured by extraction of ammonium acetate and use of the Flame Photometer37. Available phosphorus (P) was measured by Olsen method38. Soil acidity (pH) and electrical conductivity (EC) measured using a pH meter (2:1 water ratio) and an electrometer, respectively39. The measurement of magnesium and calcium was conducted through the dissolution of these elements in soil extract followed by titration40.

Data analysis

Given the normal distribution of the data based on Kolmogorov–Smirnov, a two-way analysis of variance (GLM) with partial eta squared (η²) calculated to quantify the effect sizes was used to examine the influence of woody species and season, as well as their interaction on leaf nutrient levels. In addition, the Duncan test at %5 significance level employed to compare the means of leaf nutrients and soil characteristics. An independent t-test used to compare leaf and soil nutrients between two groups of trees (needleleaf and broadleaf). These analyses were carried out using SPSS software version 23. We performed a principal component analysis (PCA) to evaluate the relationships between leaf nutrient concentrations and soil chemical properties across different woody species plantations. Prior to the analysis, all variables, including leaf nutrients and soil physico-chemical properties, were standardized to ensure comparability. Then, for each season, the significance of positive or negative correlations with the first and second axes was assessed at the 1% and 5% significance levels. The analysis was conducted using PC-ORD software (version 5)41. The present study focused on the nutrient content in young and senescent leaves during a specific growth season (spring-summer) .

%Re is equal to a nutrient in a leaf in a specific growth season (spring–summer); Nut0 was the nutrient concentration in a specific leaf at the beginning of the season (spring) and Nut1 was the nutrient concentration of the same leaf (to include maturation) at the end of the season (summer)42,43,44.

Result

Leaf nutrient

Results showed that woody species significantly affected measured leaf nutrients (except C). The seasonal effect on leaf Mg, N, P, and the C: N ratio was significant. The interaction effect between tree species and season on leaf Mg, Ca, K, N and the C: N ratio was significant (P < 0.05). The analysis revealed that leaf carbon content did not differ significantly between broadleaf and needleleaf species across the spring and summer periods (P > 0.05 (Table 1).

The effect size analysis indicated that the influence of species and the interaction between species and season on all leaf nutrient elements was strong partial eta squared (η² > 0.14), while the seasonal effect was moderate for carbon and potassium (η² = 0.06–0.14) and weak for calcium (η² = 0.01). The Pearson correlation between leaf nutrients in studied seasons and the percentage of nutrient retranslocation in the studied plantations was analyzed (Table S1).

The independent t-test showed that the levels of leaf nutrients including Mg, N, K and P were significantly greater in broadleaf species compared to needleleaf species. However, there was no significant difference in Ca content among these groups. The C: N ratio was significantly greater in needleleaf species than in broadleaf species.

In needleleaf species, nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium concentrations were consistently lower in broadleaf and remained stable across seasons. Conversely, the broadleaf species exhibited significant seasonal variation, with higher concentrations in spring. Specifically, in Quercus brantii, nitrogen content declined from 1.78% in spring to 1.25% in summer, and in Amygdalus scoparia, from 2.01 to 0.99% (Fig. 1A). Similarly, phosphorus content in Quercus brantii decreased from 29.33 mg/kg in spring to 22.33 mg/kg in summer, and in Amygdalus scoparia, from 23 to 13.66 mg/kg (Fig. 1B). In A. scoparia, potassium content significantly declined from 285.27 mg/kg in spring to 200.45 mg/kg in summer, whereas Q. brantii showed no significant seasonal change (Fig. 1C).

Although the overall calcium content did not differ significantly between the two vegetation types, the needleleaf species showed clear seasonal variation, with higher values in spring. In P. eldarica, calcium decreased from 274.33 mg/kg in spring to 199.66 mg/kg in summer, and in C. arizonica, from 409 to 320 mg/kg. Among broadleaf species, only Q. brantii showed a significant seasonal increase in calcium (170.33 in spring vs. 303.66 mg/kg in summer), while A. scoparia remained stable across seasons (Fig. 1D). Magnesium content was significantly higher in broadleaf species. Within needleleaf species, Pinus consistently had higher magnesium concentrations than Cupressus across both seasons. Among broadleaf species, A. scoparia not only showed a significant seasonal decline in magnesium (47.33 to 27 mg/kg) but also had higher levels than Q. brantii in both seasons (Fig. 1E).

The C: N ratio was significantly higher in needleleaf species (51.57) compared to broadleaf species (37.86). No significant seasonal or interspecific variation in C: N ratio was detected among needleleaf species. However, in broadleaf species, the C: N ratio increased in summer, with A. scoparia exhibiting higher values than Q. brantii in both seasons (53.35 vs. 41.72 in summer, and 26.77 vs. 26.61 in spring, respectively) (Fig. 1F).

Comparison of mean ± standard error for different tree species plantation, seasons (spring and summer) effects on leaf nutrients (lowercase letters on the columns represent significant differences at the 5% level, while varying uppercase letters denote significant differences among needleleaf and broadleaf species as determined by an independent t-test).

Nutrient retranslocation

The analysis of nutrient retranslocation (% Re) for leaf nutrients revealed significant differences among the studied species at the 5% significance level over the study period from early spring (April) to late summer (September) (Table 2).

Therefore, the nutrient retranslocation among the four species studied is as follows.

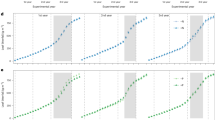

Carbon retranslocation: Cupressus > Pinus > Quercus > Amygdalus (Fig. 2A), Nitrogen retranslocation: Amygdalus > Quercus > Cupressus > Pinus (Fig. 2B), Phosphorus retranslocation: Amygdalus > Quercus > Pinus > Cupressus (Fig. 2C), Potassium retranslocation: Amygdalus > Pinus > Cupressus > Quercus (Fig. 2D), Calcium retranslocation: Pinus > Cupressus > Amygdalus > Quercus (Fig. 2E), Magnesium retranslocation: Amygdalus > Pinus > Cupressus > Quercus (Fig. 2F). Over a six-month period, Pinus leaves retranslocated all nutrients except N, Cupressus leaves retranslocated all nutrients except K and N, Amygdalus leaves retranslocated all nutrients except C, and Quercus leaves retranslocated C, N, and P. It is likely that Pinus retains 10.55% N, Cupressus retains 1.64% of K and 4.14% of Mg, Amygdalus retains 1.95% of C and Quercus retains 19.86% of K, 77.74% of Ca and 18.31% of Mg in its fallen leaves.

Soil and leaf nutrients relationship

Clear differences exist between broadleaf and needleleaf species, as evidenced by a comparison of soil and leaf chemical elements in spring (Table S2). The Quercus was classified into a distinct group due to their higher soil nutrient content (Ca, OC, N, K, and P) and lower soil C: N ratio. Amygdalus were separated from Quercus and other needleleaf species due to higher leaf nutrient content, including phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), potassium (K), and magnesium (Mg). Needleleaf species (Pinus and Cupressus) were grouped based on leaf characteristics such as higher levels of Ca and a higher C: N ratio, as well as lower soil Mg content (Fig. 3A). In summer, the broadleaf species were distinct from the needleleaf species again. Broadleaf species exhibited the highest levels of soil nutrients (OC, N, P, K and Ca) and leaf nutrients (N, Mg, P, K and Ca), placing them in a separate group. Needleleaf species were distinguished from broadleaf species based on soil Mg and C: N ratio, as well as leaf carbon and C: N ratio, with Cupressus showing higher levels of these elements compared to Pinus (Fig. 3B). Pearson correlation coefficients between soil and leaf nutrients also confirmed these results (Table S3).

Principal component analysis (PCA) of soil and leaf nutrients, K: Soil Available Potassium, P: Soil Available Phosphorus, OC: Soil Organic Carbon, N: Soil Total Nitrogen, Mg: Soil Magnesium, Ca: Soil Calcium, N Leaf: Leaf Total Nitrogen, C Leaf: Leaf Total Carbon, K Leaf: Leaf Potassium, P Leaf: Leaf Phosphorus, Ca Leaf: Leaf Calcium, Mg Leaf: Leaf Magnesium.

Discussion

Leaf nutrients

The percentage of leaf carbon did not vary significantly by species or season. However, needleleaf species had a higher carbon content than broadleaf species. This is because leaf carbon concentration is primarily determined by the proportion of structural carbohydrates and lignin in the cell wall45. The nitrogen and phosphorus content of the leaves of the needleleaf species did not change significantly between spring and summer. However, these elements were significantly higher in broadleaf species in spring than in summer. This increase in spring can be attributed to more favorable moisture and temperature conditions, as well as increased microbial activity in decomposing leaf litter. The onset of the growing season and higher nutrient uptake lead to greater accumulation of these elements in young leaves. Reduced leaf growth during the dry season, as a general response to drought, may explain the decreased leaf element concentrations in the summer. Phosphorus is essential for the metabolism of fats, proteins, and other respiratory processes and is critical in plant compounds involving nitrogen46. Higher levels of phosphorus in spring can be linked to its role in seed production and energy transfer. The reduction in available phosphorus in Iran’s arid climate is due to the presence of lime, low organic matter, and dry soil47. The higher lime content in soils under needleleaf canopies explains the lower phosphorus levels in the soil and leaves. Consistent with studies linking high potassium in plant tissues to elevated soil potassium, potassium levels were significantly higher in broadleaf species compared to needleleaf species. This study also found increased potassium levels in the soil and leaves of broadleaf species during the spring. Potassium is essential for enzymatic functions and stomatal regulation. It is also more readily available to plants through mineral weathering and salt dissolution than phosphorus and nitrogen48,49.

There was no significant difference in calcium levels between needleleaf and broadleaf trees. However, needleleaf trees had higher calcium levels in the spring than in the summer. In contrast, calcium levels in broadleaf trees, especially Quercus, were greater in the summer than in the spring. Broadleaf trees store 5 to 10% of their magnesium and a considerable amount of their calcium as pectate in the middle lamella. Cell wall calcium concentration can reach up to 50% of the total leaf calcium in soils with calcium deficiencies50. During wet seasons, increased photosynthesis and herbivore activity51 may lead to higher lignin production, which extends leaf lifespan by increasing resistance to herbivore attacks52,53.

During dry seasons, when growth periods are shorter and herbivore activity is reduced, plants produce more calcium pectate and less lignin. This reduces leaf construction costs and ensures faster growth54. Leaf structural strategies reflect calcium, carbon, and cell wall composition concentrations. Leaves with more calcium pectate have higher calcium levels because it is less costly to construct them than leaves with hemicellulose and lignin. This may explain the elevated calcium levels observed in leaves under drought conditions or in soils with adequate calcium55and consequently, the increased calcium levels in broadleaf species during summer. The measured calcium content represents the total amount of calcium in the leaves, which may not accurately reflect the amount of calcium that is physiologically active and mobile and associated with the plasma membrane–cell wall continuum. The higher calcium content in spring may result from increased uptake during early growth.

The magnesium content of broadleaf species’ leaves was significantly higher than that of needleleaf species. Since magnesium (Mg) is a fundamental component of plant growth and an integral part of chlorophyll production, seasonal variations in leaf magnesium content are particularly important in spring. For example, Amygdalus species show elevated magnesium levels due to increased photosynthetic activity, while lower levels are observed in summer. Magnesium availability is affected by factors such as bedrock properties, weathering, climate, and plant species. Competition for root absorption sites among magnesium, calcium, and potassium reduces magnesium uptake, and our results are consistent with previous research on cation competition and nutrient uptake dynamics56,57,58.

The C: N ratio in needleleaf species is significantly higher than in broadleaf species and it increased in the summer compared to the spring. Considering that there is no significant difference in carbon content between the studied species, this increase C/N is due to the lower nitrogen concentration in needleleaf species, especially in the summer season. Research indicates that the ratio of essential nutrients is more important than their concentration, and the nutrient ratio can better reflect a plant’s nutritional status, and it is less affected by growth-related dilution59. Additionally, water stress leads to reduced leaf area and changes in carbon uptake, which affects the C: N ratio60.

The findings of this study support both initial hypotheses. Leaf nutrient concentrations were more strongly influenced by tree species than seasonal variation, highlighting the dominant role of species-specific traits in nutrient allocation. Furthermore, indigenous broadleaf species consistently exhibited higher levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium compared to exotic needleleaf species. This pattern likely reflects the greater adaptability of native species to local environmental conditions and their enhanced nutrient uptake efficiency.

Nutrient retranslocation

A key method for assessing the ecological capacity of forests is to study nutrient retranslocation in trees. Trees respond to adverse environmental conditions by increasing the retranslocation and storage of nutrients in their trunks, leading to greater differences in nutrient levels between leaves at the beginning and end of the growing season61,62. In this study, increased nutrient retranslocation from summer leaves (September) indicate a weak nutrient cycling system in the forest stand. Regarding the negative carbon retranslocation observed in Amygdalus species, it is important to note that carbon is primarily found in cell wall structural compounds, such as lignin and polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectins). Leaf lignin accumulates, and cellulose concentration decreases under high irradiance and photosynthesis conditions. In our study, the summer season was characterized by intense sunlight. Given the life form of Amygdalus and the mechanisms, such conditions are likely limited and complicated carbon translocation in these species. Positive percentages, on the other hand, indicate lower levels. By the end of the study period, nutrients such as phosphorus had been used or stored in other tissues, which prevented their return to the soil through leaf fall.

The higher nitrogen retranslocation in broadleaf species, especially Amygdalus, compared to needleleaf species, as well as the phosphorus retranslocation in all four species at the end of the period, are due to the role of these nutrients in vegetative and reproductive growth, such as photosynthesis, energy transfer, and seed and fruit production, at the beginning of the growing season. Deciduous broadleaf species such as Quercus and Amygdalus produce more leaves during the growing season and shed them annually, investing more nutrients for faster growth in a shortened growing seasons61. So, our study revealed that, in contrast to evergreen trees, deciduous trees demonstrated a markedly higher rate of nitrogen and phosphorus retranslocation. The retranslocation of P (24.43%) was higher than that of N (20.78%), indicating that plant uptake of P was greater than that of N, which is an adaptive strategy of species in degraded environments63. However, the retranslocation of P and N values in this study are lower than those (64.9% and 62.1%, respectively) reported in other global terrestrial forest ecosystems64. The change of P retranslocation is higher influenced by soil and climate, while variantion in N retranslocation relates more to plant functional type65. In contrast, needleleaf species have specialized techniques for growing in nutrient-poor soils and prolonging leaf lifespan to maximize growth rates and minimize nutrient loss at the end of the season66,67. Nutrient retranslocation increases with lower soil nutrient levels and significantly decreases when nutrients are more readily available in the soil68. Our study showed that nitrogen and phosphorus retranslocation were coupled and increased concurrently and correlated with each other, consistent with other studies that confirm the relationship between nitrogen and phosphorus (e.g.64,67,69). This was also supported by Liebig’s law of the minimum70, which states that multiple nutrient balances as well as nutrient availability are essential for plant growth. The increased levels of K, Ca and Mg in Quercus at the end of the period indicate return of these nutrients to the soil. Thus, this decreases the need to store these elements in other tissues. The increase in Ca and Mg concentrations is due to their immobility within the plant and their structural role in the cell walls of late-season leaves50.

Soil and leaf nutrients relationship

Our results revealed distinct differences in the dynamic relationships between soil and leaf nutrient elements in needleleaf and broadleaf species. These species respond differently to variations in soil nutrient availability and employ distinct resource utilization strategies. Needleleaf species exhibit greater tolerance to nutrient scarcity and demonstrate less variability in leaf traits, which is characteristic of plants with a slow resource strategy10,11. This strategy supports survival under limited resource conditions and low growth rates71,72,73,74. In contrast, deciduous broadleaf species are more sensitive to nutrient availability and quickly adjust to resource fluctuations, characteristic of species exhibiting the fast resource strategy75. Nutrient levels in the soil and leaves of broadleaf species were higher, indicating their ability to store and utilize resources efficiently before leaf fall, which is a good adaptation to dry conditions76,77.

During the spring season, a significant correlation was observed between the concentrations of potassium (K), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) in the leaves and their corresponding levels in the soil. These relationships suggest that foliar nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations are not regulated solely by their individual availability in the soil. Instead, nitrogen uptake appears to be co-limited by both soil nitrogen and phosphorus levels, and similarly, phosphorus acquisition is influenced by both soil phosphorus and nitrogen availability. This interdependence is likely attributable to the synergistic roles of N and P in vital physiological processes such as protein synthesis, energy transfer, and photosynthesis. The findings underscore the importance of nutrient interactions in determining foliar nutrient composition and support the concept that multi-nutrient regulation, rather than single-nutrient limitation, governs nutrient assimilation in forest species under varying seasonal and edaphic conditions.

Changes in leaf nutrient concentrations are linked with changes in their concentrations in the soil63,78. Because of the interdependent roles of N and P in photosynthesis, broadleaf species grow faster than needleleaf species in the spring and have higher concentrations of N and P in their leaves. This trend was observed in Amygdalus species, which exhibited faster growth, and a shrub-like form compared to Quercus. These findings align with those of another study79. Therefore, an increase in leaf nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations occurs when both elements are abundantly available in the soil. This pattern illustrates that the combined effects of soil N and P, rather than their individual effects, account for the significant changes in leaf nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations. Magnesium is crucial for plant cell walls where it exists as Mg2+-pectate (5–10%), but in the cytoplasm it exists as Mg2+ and soluble salts. The trade-offs among structural Mg2+ pectate and metabolic Mg chlorophyll are strongly related to magnesium nutritional status, as higher concentrations of magnesium associated with chlorophyll reflect a deficiency in the soil48. In summer, the concentrations of N, P, K, and Ca in leaves were also correlated with their concentrations in the soil. In this season, although there is a clear distinction between needleleaf and broadleaf species, the broadleaf species (Amygdalus and Quercus) showed greater similarity in terms of soil and leaf nutrients. Higher-nutrient leave in broadleaf species was as expected. The ongoing decomposition of organic matter during the studied seasons resulted in increased organic content in the soil, enhancing its fertility. More fertile soils can provide a richer supply of nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, to support plant development80. An extensive body of literature suggests that needleleaf species with thick, robust, long-lived leaves usually have low concentrations of nutrients and chlorophyll. Furthermore, these leaves are characterized by low water content and high levels of fiber, lignin, and cellulose. These properties are characteristic of plants inhabiting infertile soils, where they represent important ecological adaptations to the trade-offs among plant growth and resource allocation important to survival72,81. In summary, seasonal variations in temperature, rainfall and solar radiation affect the processes of photosynthesis, respiration, transpiration and nutrient uptake in plants82. These relationships vary between species and therefore affect the soil attributes, such as temperature, moisture and organic matter decomposition rate83, which alter leaf nutrient concentrations.

These findings confirm our third hypothesis, demonstrating that the relationship between soil and leaf nutrient concentrations is not static but varies significantly across seasons and tree species. Broadleaf and needleleaf species exhibited distinct nutrient uptake strategies, and the strength and nature of correlations between soil and leaf nutrient levels shifted between spring and summer. These seasonal dynamics, influenced by climatic conditions and species-specific physiological traits, underscore the complex interactions governing nutrient cycling in forest ecosystems.

Conclusions

The arid and semi-arid ecosystems of the Zagros are critical to Iran’s ecological and socioeconomic sustainability. In some areas, forest degradation is so severe that soil erosion has exposed the underlying bedrock. Under these circumstances, natural regeneration is not possible, so afforestation through artificial regeneration is necessary to restore forest cover. This study revealed clear, species-specific responses to seasonal variations in the dynamics of nutrients between soil and leaves, due to the different growth and survival strategies of the species under varying environmental conditions. Simultaneous sampling at the beginning and end of a six-month period (early April to late September) in 30-year-old plantations showed that broadleaf species (Quercus brantii and Amygdalus scoparia) had significantly higher concentrations of essential macronutrients (N, P, K, and Mg) in their leaves than needleleaf species (Pinus eldarica and Cupressus arizonica). Seasonal patterns of nutrient retranslocation followed the order: Ca < C < K < Mg < N < P, highlighting the importance of nitrogen and phosphorus during early growth and these nutrients are likely to be limited in arid and semi-arid areas. Nutrient return through leaf shedding also varied by species, with Q. brantii showing the highest contribution of K, Ca and Mg to the soil. In contrast, C. arizonica exhibited relatively higher returns of K and Mg among needleleaf species. From an ecological perspective, the results underscore the superior capacity of Q. brantii to enhance soil fertility under severe conditions, supporting its prioritization in reforestation programs. The consistent performance of C. arizonica in nutrient cycling also justifies its use among needleleaf species. These findings have significant policy implications for natural resource managers. Species selection in reforestation programs should consider nutrient feedback mechanisms to ensure long-term soil health and forest sustainability. In the context of climate change, understanding species-specific nutrient demands and return patterns can also guide the design of adaptive planting strategies that maximize ecosystem resilience under increasing drought stress.

Future research should expand on these findings by examining the long-term impact of species composition on soil nutrient levels, microbial communities, and the potential for carbon sequestration under different climate conditions. This knowledge is crucial for creating climate-resilient, evidence-based forest restoration strategies in dryland regions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [Mirzaei] on request.

References

Jazirehi, M. H. & Ebrahimi Rostaghi, M. Silviculture in Zagros, 2 Edn. (University of Tehran Press, 2013).

Taghipour, K. et al. Assessing changes in soil quality between protected and degraded forests using digital soil mapping for semiarid oak forests, Iran. Catena. 213, 106204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106204 (2022).

Vidal, D. F. et al. Intercropping N-fixing shrubs in pine plantation forestry as an ecologically sustainable management option. Ecol. Manag. 437, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.01.023 (2019).

Kvitko, M. et al. Woody artificial plantations as a significant factor of the sustainable development at mining & metallurgical area. E3S Web Conf. 280, 06005 (2021).

Tian, D. et al. Global leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry and their scaling exponent. Natl. Sci. Rev. 5 (5), 728–739. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwx142 (2018).

Pandey, N. Role of plant nutrients in plant growth and physiology. In Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance (eds Hasanuzzaman, M. et al.). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-9044-8_2 (Springer, 2018).

Shi, X. et al. Variable leaf nitrogen-phosphorus ratios and stable resorption strategies of Kandelia obovata along the southeastern Coast of China. Ecol. Manag. 560, 121822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.121822 (2024).

Estiarte, M., Campioli, M., Mayol, M. & Peñuelas, J. Variability and limits of nitrogen and phosphorus resorption during foliar senescence. Plant. Commun. 4 (2), 100503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100503 (2023).

Sophia, G., Caldararu, S., Stocker, B. D. & Zaehle, S. Leaf habit drives leaf nutrient resorption globally alongside nutrient availability and climate. Biogeosciences 21 (18), 4169–4193. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-21-4169-2024 (2024).

Yan, T., Zhu, J. & Yang, K. Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus resorption of Woody species in response to Climatic conditions and soil nutrients: a meta-analysis. J. For. Res. 29, 905–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-017-0519-z (2018).

Xu, M. et al. Global scaling the leaf nitrogen and phosphorus resorption of Woody species: revisiting some commonly held views. Sci. Total Environ. 788, 147807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147807 (2021).

Wang, X., Wang, R. & Gao, J. Precipitation and soil nutrients determine the Spatial variability of grassland productivity at large scales in China. Front. Plant. Sci. 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.996313 (2022).

Wright, I. J. et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428 (6985), 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02403 (2004).

He, M. et al. Scaling the leaf nutrient resorption efficiency: nitrogen vs phosphorus in global plants. Sci. Total Environ. 729, 138920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138920 (2020).

Sun, X. et al. Widespread controls of leaf nutrient resorption by nutrient limitation and stoichiometry. Funct. Ecol. 37 (6), 1653–1662. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14318 (2023).

Lira-Martins, D. et al. Tropical tree branch-leaf nutrient scaling relationships vary with sampling location. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 877. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00877 (2019).

Beaumelle, L., De Laender, F. & Eisenhauer, N. Biodiversity mediates the effects of stressors but not nutrients on litter decomposition. Elife 9, e55659. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.55659 (2020).

Zhou, G. et al. Seasonal variability of functional traits of understory herbs in a broad-leaved Korean pine forest. Russ J. Ecol. 50, 583–586. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1067413619060146 (2019).

Karamian, M., Mirzaei, J., Heydari, M., Kooch, Y. & Labelle, E. R. Seasonal effects of native and non-native Woody species on soil chemical and biological properties in semi-arid forests, Western Iran. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 23, 4474–4490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-023-01365-6 (2023).

Erfanifard, Y., Feghhi, J., Zobeiri, M. & Namiranian, M. Spatial pattern analysis in Persian oak (Quercus Brantii var. persica) forests on B&W aerial photographs. Environ. Monit. Assess. 150, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-008-0227-4 (2009).

Pourreza, M., Hosseini, S. M., Sinegani, A. A. S., Matinizadeh, M. & Alavai, S. J. Herbaceous species diversity in relation to fire severity in Zagros oak forests, Iran. J. Res. 25, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-014-0436-3 (2014).

Sagheb Talebi, K., Sajedi, T. & Pourhashemi, M. Forests of Iran: A Treasure from the Past, a Hope for the Future (No. 15325). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7371-4 (Springer, 2014).

Rostami, N., Heydari, M., Uddin, S. M., Lucas-Borja, E., Zema, D. A. & M., & Hydrological response of burned soils in croplands, and pine and oak forests in Zagros forest ecosystem (western Iran) under rainfall simulations at micro-plot scale. Forests 13 (2), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13020246 (2022).

Mirzaei, Heydari, M. & Prevosto, B. Effects of vegetation patterns and environmental factors on Woody regeneration in semi-arid oak-dominated forests of Western Iran. J. Arid Land. 9, 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-017-0013-7 (2017).

Tárrega, R., Calvo, L., Taboada, Á., García-Tejero, S. & Marcos, E. Abandonment and management in Spanish Dehesa systems: effects on soil features and plant species richness and composition. Ecol. Manag. 257 (2), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.10.004 (2009).

Jalilvand, H. Development of dual nutrient diagnosis ratios for basswood, American beech, and white Ash. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 3 (2), 121–130 (2001).

Hashemi, S. F., Hojjati, S. M., Nasr, S. M. H. & Jalilvand, H. Comparison of nutrient elements and elements retranslocation of Acer velutinum, Zelkova carpinifolia, and Pinus brutia in Darabkla-Mazindaran. J. For. 4 (2), 175–185 (2012).

Salehi, A. & Pavand Dro, A. Nutrient return and nutrient retranslocation in Acer velutinum Boiss in Caspian forest (Case Study:Nav/Asalem). JWFST 20 (1), 51–64 (2013).

Ghazanshahi, J. Soil and Plant Analysis 311 (Homa Publication, 1997).

Miles, P. H., Wilkinson, N. S. & McDowell, L. R. Analysis of Minerals for Animal Nutrition Research 117 (Department of Animal Science, University of Florida, 2001).

Bouyoucos, G. J. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of soils 1. Agron. J. 54 (5), 464–465. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1962.00021962005400050028x (1962).

Famiglietti, J. S., Rudnicki, J. W. & Rodell, M. Variability in surface moisture content along a hillslope transect: rattlesnake hill, Texas. J. Hydrol. 210 (1–4), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(98)00187-5 (1998).

Blake, G. R. & Hartge, K. H. Bulk density. in Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Methods, vol. 5, 363–375.

Walkley, A. & Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid Titration method. Soil. Sci. 37, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003 (1934).

Bremner, J. M. Nitrogen-total. Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods, vol. 5, 1085–1121. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssabookser5.3.c37 (1996).

Black, C. A. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part L 545–566 (ASA, 1986).

Moreno, G., Obrador, J. J. & García, A. Impact of evergreen Oaks on soil fertility and crop production in intercropped Dehesas. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 119 (3–4), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2006.07.013 (2007).

Olsen, S. R. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate (No. 939) 1–19 (US Department of Agriculture, 1954).

Kalra, Y. P. & Maynard, D. G. Methods Manual for Forest Soil and Plant Analysis, Vol. 319 (Northern Forestry Centre, 1991).

Pereira, C. M., Neiverth, C. A., Maeda, S., Guiotoku, M. & Franciscon, L. Complexometric Titration with potenciometric indicator to determination of calcium and magnesium in soil extracts. Rev. Bras. Ciênc Solo. 35 (4), 1331–1336. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832011000400027 (2011).

Ter Braak, C. J. F. Reference Manual and User’s Guide to Canoco for Windows: Software for Canonical Community Ordination (Version 4) (eds Smilauer, P.) (Microcomputer Power, 1998).

de las Heras, J., Hernández-Tecles, E. J. & Moya, D. Seasonal nutrient Retranslocation in reforested Pinus halepensis mill. Stands in Southeast Spain. New For. 48, 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-016-9564-2 (2017).

Seidel, F. et al. Seasonal phosphorus and nitrogen cycling in four Japanese cool-temperate forest species. Plant. Soil. 472 (1), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-021-05251-x (2022).

Li, W., Huang, G. & Zhang, H. Enclosure increases nutrient resorption from senescing leaves in a subalpine pasture. Plant. Soil. 457, 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04733-8 (2020).

Ma, J. et al. Tree size influences leaf shape but does not affect the proportional relationship between leaf area and the product of length and width. Front. Plant. Sci. 13850203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.850203 (2022).

Ceulemans, T., Hulsmans, E., Berwaers, S., Van Acker, K. & Honnay, O. The role of above-ground competition and nitrogen vs. phosphorus enrichment in seedling survival of common European plant species of semi-natural grasslands. PLOS ONE. 12 (3), e0174380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174380 (2017).

Ebadi Nahari, A., Alikhani, H. A., Saghfi, M. & Khanloo, D. Determination of dissolution of inorganic and inorganic insoluble phosphates by Pseudomonas fluorescens. In Proceeding of First National Conference on Modern Agricultural and Natural Resources (2018).

Hawkesford, M. et al. Functions of macronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants 135–189 (Academic Press, 2012).

Shahoei, S. The Nature and Properties of Soils 900 (Kurdistan University Publication, 2006).

White, P. J., Broadley, M. R., El-Serehy, H. A., George, T. S. & Neugebauer, K. Linear relationships between shoot magnesium and calcium concentrations among angiosperm species are associated with cell wall chemistry. Ann. Bot. 122 (2), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcy062 (2018).

Chen, G., Hobbie, S. E., Reich, P. B., Yang, Y. & Robinson, D. Allometry of fine roots in forest ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 22 (2), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13193 (2019).

Villar, R., Robleto, J. R., De Jong, Y. & Poorter, H. Differences in construction costs and chemical composition between deciduous and evergreen Woody species are small as compared to differences among families. Plant. Cell. Environ. 29 (8), 1629–1643. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01540.x (2006).

Popper, Z. A. et al. Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: from algae to flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 62, 567–590. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103809 (2011).

Mladkova, P., Mladek, J., Hejduk, S., Hejcman, M. & Pakeman, R. J. Calcium plus magnesium indicates digestibility: the significance of the second major axis of plant chemical variation for ecological processes. Ecol. Lett. 21 (6), 885–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12956 (2018).

Xing, K. et al. Relationships between leaf carbon and macronutrients across Woody species and forest ecosystems highlight how carbon is allocated to leaf structural function. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 674932. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.674932 (2021).

Römheld, V. & Kirkby, E. A. Magnesium functions in crop nutrition and yield. In Proceedings of a Confernce in Cambridge 151–171 (2007).

Fageria, N. K. The Use of Nutrients in Crop Plants. https://doi.org/10.1556/crc.37.2009.1.18 (CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 2009).

Yan, B. & Hou, Y. Effect of soil magnesium on plants: a review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 170 (2), 022168. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/170/2/022168 (2018).

Flückiger, W. & Braun, S. Critical limits for nutrient concentrations and ratios for forest trees—a comment. Empirical Critical Loads for Nitrogen 273–280 (Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape (SAEFL), 2003).

Singh, B. & Singh, G. Influence of soil water regime on nutrient mobility and uptake by Dalbergia sissoo seedlings. Trop. Ecol. 45 (2), 337–340 (2004).

Brant, A. N. & Chen, H. Y. Patterns and mechanisms of nutrient resorption in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant. Sci. 34 (5), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.2015.1078611 (2015).

Johnson, D. W. & Turner, J. Tamm review: nutrient cycling in forests: A historical look and newer developments. Ecol. Manag. 444, 344–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.04.052 (2019).

Lin, Y. et al. Available soil nutrients and water content affect leaf nutrient concentrations and stoichiometry at different ages of Leucaena leucocephala forests in dry-hot Valley. J. Soils Sediments. 19, 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-018-2029-9 (2019).

Hu, R., Liu, T., Zhang, Y., Zheng, R. & Guo, J. Leaf nutrient resorption of two life-form tree species in urban gardens and their response to soil nutrient availability. PeerJ 11, e15738. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15738 (2023).

Tang, L. Y., Han, W. X., Chen, Y. H. & Fang, J. Y. Resorption proficiency and efficiency of leaf nutrients in Woody plants in Eastern China. J. Plant. Ecol. 6 (5), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtt013 (2013).

Chen, X., Chen, H. Y., Searle, E. B., Chen, C. & Reich, P. B. Negative to positive shifts in diversity effects on soil nitrogen over time. Nat. Sustain. 4 (3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00641-y (2021).

Vergutz, L., Manzoni, S., Porporato, A., Novais, R. F. & Jackson, R. B. Global resorption efficiencies and concentrations of carbon and nutrients in leaves of terrestrial plants. Ecol. Monogr. 82 (2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-0416.1 (2012).

Xu, L. et al. Effects of nitrogen addition on leaf nutrient stoichiometry in an old-growth boreal forest. Ecosphere 12 (1), e03335. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3335 (2021).

Shah, J. A. et al. Linkages among leaf nutrient concentration, resorption efficiency, litter decomposition and their stoichiometry to canopy nitrogen addition and understory removal in subtropical plantation. Ecol. Process. 13 (1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-024-00507-7(2024.

Marschner, P. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd edn (Elsevier/Academic, 2012).

Grime, J. P. Plant Strategies, Vegetation Processes, and Ecosystem Properties (Wiley, 2006).

Craine, J. M. Resource Strategies of Wild Plants. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400830640 (Princeton University Press, 2009).

Reich, P. B. The world-wide ‘fast–slow’plant economics spectrum: a traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 102 (2), 275–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12211 (2014).

Damián, X. et al. Natural selection acting on integrated phenotypes: covariance among functional leaf traits increases plant fitness. New. Phytol. 225 (1), 546–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16116 (2020).

Zhang, Y. L. et al. Contrasting leaf trait responses of conifer and broadleaved seedlings to altered resource availability are linked to resource strategies. Plants 9 (5), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9050621 (2020).

Rossatto, D. R., Carvalho, F. A. & Haridasan, M. Soil and leaf nutrient content of tree species support deciduous forests on limestone outcrops as a eutrophic ecosystem. Acta Bot. Bras. 29 (2), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-33062014abb0039 (2015).

Bai, K. et al. Leaf nutrient concentrations associated with phylogeny, leaf habit and soil chemistry in tropical karst seasonal rainforest tree species. Plant. Soil. 434, 305–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3858-4 (2019).

Firn, J. et al. Leaf nutrients, not specific leaf area, are consistent indicators of elevated nutrient inputs. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3 (3), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0790-1 (2019).

Reich, P. B. et al. Evidence of a general 2/3-power law of scaling leaf nitrogen to phosphorus among major plant groups and biomes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 277 (1683), 877–883. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1818 (2010).

Furey, G. N. & Tilman, D. Plant biodiversity and the regeneration of soil fertility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 (49), e2111321118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2111321118 (2021).

Miatto, R. C., Wright, I. J. & Batalha, M. A. Relationships between soil nutrient status and nutrient-related leaf traits in Brazilian Cerrado and seasonal forest communities. Plant. Soil. 404, 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-016-2796-2 (2016).

Tkemaladze, G. S. & Makhashvili, K. A. Climate changes and photosynthesis. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 14 (2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aasci.2016.05.012 (2016).

Certini, G. & Scalenghe, R. The crucial interactions between climate and soil. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 159169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159169 (2023).

Funding

(This research was supported by Ilam university)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M, M.H, Y. K and planned the work and did analysis and manuscript preparation.M.K conducted field work, soil and leaf analysis.D. D helped in manuscript preparation and final English editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publish the article in this journal.

Consent to participate

All authors consent to participate in this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karamian, M., Mirzaei, J., Heydari, M. et al. Temporal variation of leaf nutrient retranslocation in exotic and indigenous tree species in Zagros forests, Iran. Sci Rep 15, 22505 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09125-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09125-5