Abstract

Significant energy input is needed for thermodynamic activities, including cooling, heating, and manufacturing, which frequently occur over a range of temperatures. Phase change materials (PCMs) are frequently employed in indirect thermal energy storage systems to handle this requirement effectively. Nevertheless, functionality is limited by their intrinsically low ability to conduct heat. The current research uses a two-step synthesis process to add copper (Cu), aluminium (Al), and zinc (Zn) nanoparticles at a 1.5% weight ratio to improve the thermal characteristics of both PCMs: D-Mannitol and Myristic acid. Therminol-66 was used as a temperature conduction fluid during testing and thermophysical characterization of the resultant combination nano-PCMs. The coefficient of thermal conductivity was greatly enhanced by the addition of nanoparticles; Ma-Cu and My-Cu achieved values of 0.42 W/mK and 0.36 W/mK, respectively. Ma-Zn and My-Zn achieved heat transfer rates of 3956.40 kJ and 1451.51 kJ, respectively, indicating an improvement in heat transfer capability. These improvements show how hybrid nano-PCMs have a great deal of promise for raising heating and cooling systems in a range of environmental applications and clean energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In thermal energy storage (TES) systems, temperature conductivity is a crucial thermophysical feature that is essential to heat transmission methods for substances. Phase change material (PCMs) is the main component used in TES implementations; they may either be eutectic, organic substances, or polymeric1. PCMs are extensively used in a variety of TES systems, such as direct-contact thermal retention in radiators, indirect-contact passive heat storage, & temperature preservation to regulate excessive heat requirements. Verma and Singal’s research illustrates that although several phase-shifting materials with unique thermophysical characteristics are currently studied for both heating and cooling applications, successful implementation has frequently eluded researchers2.

Experts are looking into multi-phase devices that include both active and passive PCMs to overcome the restrictions of storing electricity. Furthermore, attempts to improve PCMs’ thermophysical features by adding micron-sized modifications have already been made, however, the intended gains in thermal conductivity remain to be realized3,4,5. A component from the natural PCM group, paraffin is abundantly readily obtainable and utilized intensively in TES. Paraffin’s inherently low thermal conductivity hinders the efficiency of heat absorption and release when the substance is used for storing heat in photoelectric detectors. For energy-efficient usage, such as air conditioning and heating, the technology known as TES requires an effective medium for storing. The thermal energy system method relies on both the latent and sensible heat capacities of the material, as well as the quantity of electricity that is received and released. As a result, Farid et al. showed that TES may increase with higher thermal permeability. Nanomaterials are substances that can be effectively dispersed across a liquid or mixture to alter its thermophysical features to meet the needs of various thermal-energy programs, according to study and theory6. The properties of dual eutectic proportions of solid–liquid PCMs were examined by Roget et al. Nevertheless, important thermodynamic properties like heat transfer and electrical conductivity weren’t included in the measurements during experimentation7. Utilizing cyclohexane in combination with nanoparticles of copper oxide at varying mass levels, Ne-PCM samples have been employed to analyse the freezing temperatures and density levels for the various mixtures8. The outcomes demonstrated that specimens in the solid phase exhibited a nonmonotonic enhancement at quantities exceeding two percent, while materials in the state of liquid strengthened as the total amount of nanoparticles climbed12.

Enhancing engine cooling system productivity by the use of a composition of water tiny amount of Al2O3 in steady-state conditions. A 1% volumetric addition of the nanofluid made of Al2O3 resulted in a 30% increase in conditioning efficiency of the system11. Yu et al. looked at how carbon nanomaterials affected the conductive properties of concentrations made of boiling wax. The findings indicated that thermal conductivity of the mixture improves as the charcoal supplement loading increases, with the amount and shape of the additions having a major influence on the entire rise in heat transfer12. Thermal transfer effectiveness and general system effectiveness can be greatly enhanced by integrating TES with collecting systems. Specifically, nanocomposites can be employed to enhance the thermal performance of paraffin-based PCMs, in absorber devices. Experimental studies have been conducted to measure the thermal conductivity of nanofluids in some investigations, having an emphasis on the addition of metallic oxides and nanomaterials13. The two most frequently utilized oxide nanoparticles in research studies are Al2O3 and CuO14.

To improve precipitation kinetics, nitrate of aluminium tiny particles, that act as self-nucleating substances, have been mixed with pentad-Mannitol (PE), a solid–solid PCM, in nanocomposite phase transition materials. PE with 3.0 weight percent nano-AIN, according to experimental results, shows solid–solid phase change behaviour when heated without excessive cooling through cooling down, preserving steady phase transition energies15.

Zheng et al. investigated ways to use enclosed phase-change substance (EPCMs) to improve the transfer of heat through convection in solar energy harvesting devices. These devices efficiently transmit warm energy over several cycles of recharging and releasing by circulating HTF circulating within the EPCM capsules. Their results showed that EPCM-based systems effectively save and recover heat energy, improving the total energy handling of the structure16.

The molecular designs of polyol-based PCMs, such as D-Mannitol and myristic acid, which contain several large-polarity hydroMyl categories, are responsible for their substantial energy conservation capabilities17. Nevertheless, the heat conductance of such substances is quite modest18, which restricts how effectively they may transfer heat to the adjacent thermodynamic medium. The ability of the latent heat storage system to efficiently store and discharge steam through periodic phase shifts is thus negatively impacted. Therefore, improving D-Mannitol’s heat conductivity has emerged as a crucial study topic. Much work has been done recently to increase the thermal efficiency of traditional PCMs. Creating PCM hybrids by combining PCMs with exceptionally porous metallic foams has been one strategy. Li and others16 created aggregates by impregnating abrasive hydrophilic copper (Cu) foams with D-mannitol. The boiling point of Cu foam-templated mixtures was five times that of purified D-mannitol. In a solar-thermal power retention framework, such components allowed for an 85.8% heat retrieval rate. Studies on polyol PCM/metal foam composites remains limited, considering these encouraging findings. The melting properties and thermal physical characteristics of PCM/metal foaming mixtures have been examined through simulation and laboratory studies19,20. Jin et al. investigated how the pore size of copper foam affects the melting speed and thermal conductivity of paraffin/copper foam composites. Composites with pore sizes of 30 and 50 ppi showed comparable dissolving rates at an overheated wall that reached 30 K, both of which were significantly quicker compared to those with 15 ppi foam. Their ultraviolet thermographic investigation showed notable variations in temperature among paraffin & metal foam following melting, suggesting the presence of significant thermal contact resistances (TCRs), even though shorter, small pores can enhance the thermal efficiency of PCM/metal foam composites20. Numerous methods to enhance PCM effectiveness and heat transfer have been shown in recent studies. Cu-based nano-PCM networks, for instance have demonstrated only modest ambient temperature increase (≈ 0.1 K) in solar-assisted underfloor heating projects, suggesting low efficiency in actual thermal power plants21,22,23. Similarly, B4C-enhanced paraffin composites reported up to a 67% an improvement in thermal conductivity accompanied by a decrease in latent heat capacity at higher nanoparticle loadings. Studies using Y2O3 and B4C nanoparticles in Myristic Acid or RT44HC PCMs confirmed enhancements in conductivity and Cp but yielded marginal improvements in overall system efficiency. In multi-component PCM blends used for data center cooling, thermal response varied significantly with flow rate and composition, revealing complexity in thermal regulation under dynamic conditions. While these studies validate the potential of nanoparticle-enhanced PCMs, most focus on single PCM-nanoparticle systems, limited temperature applications, or simulations without broad performance analysis24,25,26,27.

In contrast, this study introduces a dual-PCM system (D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid) enhanced with three different metal nanoparticles (Cu, Al, Zn) at a uniform 1.5 wt%, evaluated with a system for storing thermal energy with multiple temperatures. Despite significant advancements in PCMs remain a critical limitation, reducing how efficiently they are in transferring heat. While nanoparticle modification shows potential as a promising approach, comprehensive studies exploring the combined effects of multiple nanoparticles-such as copper (Cu), aluminum (Al), and zinc (Zn)-on the thermo-physical properties and performance of PCMs like D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid remain scarce. Furthermore, limited research has explored the application of these multi-temperature heating storage devices, composite nano-PCMs are necessary for workable, practical uses.

This study addresses current limitations in phase change material (PCM) research by synthesizing hybrid nano-PCMs through a two-step method, incorporating 1.5% weight of copper (Cu), aluminum (Al), and zinc (Zn) nanoparticles into two organic PCMs: D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid. The primary objective is to enhance the thermo-physical properties of these materials to improve their overall thermal efficiency. The synthesized hybrid nano-PCMs are evaluated within a multi-temperature thermal energy storage system, using Therminol-66 as the heat transfer fluid, with a focus on optimizing heat transfer rates and energy performance across varied temperature ranges. A key novelty of this study lies in the combined use of two distinct organic PCMs and three different metal nanoparticles, enabling a comparative assessment of six unique hybrid formulations. Unlike prior studies that often examine a single PCM or nanoparticle type in isolation, this research offers a comprehensive analysis of material enhancement and system-level performance. By systematically characterizing thermal conductivity, diffusivity, specific heat, and heat transfer behavior, and validating results against the baseline PCMs, the study identifies the most effective combinations for practical applications. These findings provide a new pathway for developing scalable, energy-efficient, and versatile thermal storage solutions adaptable to diverse industrial needs.

Materials and methods

Synthesis method

In this study, copper (Cu), aluminum (Al), and zinc (Zn) nanoparticles was used on their high thermal conductivities, chemical stability, availability, and compatibility with the chosen phase change materials (PCMs)-D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid. Copper nanoparticles were selected for their excellent thermal conductivity (~ 398 W/m−1 K), which is among the highest for metals, Aluminum nanoparticles offer a good balance between thermal enhancement (~ 237 W/m−1 K) and low cost. Their lower density and corrosion resistance make them favorable for long-term stability in thermal systems, and zinc nanoparticles, with thermal conductivity around 116 W/m−1 K, were chosen for their moderate enhancement capability and chemical compatibility with organic PCMs. Zn also has a relatively low environmental impact, making it a sustainable choice.

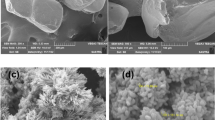

Two different procedures were followed to create the D-Mannitol and myristic acid nanocomposites for this work: TSR instruments and solutions, India, provided aluminium (AI), copper (cu), and zinc (Zn) nanoparticles with a mean size of 40 nm and 99.9% purity level. Despite the use of surfactants as well, these nanoparticles were added straight to the melted stages of myristic acid and D-Mannitol, preserving to 0.1 mg was used to thoroughly prepare the sample, making certain of the precise mass ratio. First, the nanoparticles were magnetically stirred for 30 min at a regulated temperature to scatter them throughout the liquid D-Mannitol and myristic acid. To release confined gases, the D-Mannitol and myristic acid were heated to 120 °C and 90 °C on a hotplate, accordingly, and then degassed for a period of time at 105 °C in a vacuum oven. Ultrasonic absorption sonication was used for five hours at 40 kHz and 200 watts of power to produce a uniform dispersion of nanoparticles while keeping the temperature high. This thorough process of synthesis made sure that the nanoparticles were formed while keeping the temperature high. This meticulous synthesis process ensured uniform incorporation of the nanoparticles into the nanocomposites.

Thermophysical properties

The thermophysical properties were evaluated using the Hot Disk Thermal Analyzer TPS 2500S. For each measurement, a 5-g sample with 8 mm thickness and 28 mm diameter, was produced. To ensure reliability, each test was performed three times, with the average results recorded. The measurements were obtained with an accuracy of ± 5%.

Experimentation

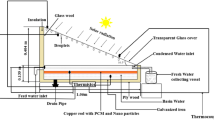

As shown in Fig. 1, the setup for the experiment includes a solar dish collector, an oil tank, comprised two latent heat thermal energy storage tanks (PCHES 1 and 2), a circulation pump, and a temperature recovery unit. It also included a 3 m2 solar dish collector equipped with a high-reflectivity (96%) aluminium-glazed surface reflecting plate that promotes the movement of the heat transmission fluid (HTF) concentrated solar energy onto the receiver’s surface.

To minimize heat loss, the flow conduits are wrapped with a 0.03 m-thick cotton rope insulator, while the oil storage tanks, thermal storage units, and the heat recovery system are externally insulated with a 0.06 m layer of glass wool. To guarantee system integrity, many leak checks were conducted on the piping and tanks. For this investigation, the HTF chosen was Therminol-66.

Phase change materials (PCMs) with varying melting points are used in the system’s design for capturing and releasing roughly 4000 kJ of heat energy. Myristic acid and D-Mannitol, known for their high latent heat of fusion, are utilized as phase change materials due to their superior energy storage capacity per unit mass and volume. The PCMs are kept in two distinct tanks, one for D-mannitol and the other for myristic acid, which are arranged to decrease melting temperatures.

Containers 1 and 2 successively receive the hot HTF from the solar receiver during charging with transfers heat to the PCMs. As a result, heat was successfully stored by the PCMs melting and absorbing thermal energy. In order to allow colder HTF to absorb heat as the PCMs solidify and release the energy they have stored; the flow direction is switched during the releasing phase after the PCMs have completely melted. Throughout these cycles, thermocouples positioned at different sites track the HTF temperature to evaluate system performance.

Performance parameter analysis

The parameters considered for assessing system performance include the energy contained in the heat transfer fluid (HTF) from the parabolic trough collector (PTC), the energy stored in the phase change materials (PCMs) during charging, the energy released by the PCMs during discharging, and the overall energy efficiency when utilizing finned encapsulated PCMs. Equations (1) and (2), developed by Gong and Mujumdar28, are used to calculate the heat release rate \({Q}_{c. PCM1}\) & \({Q}_{c.PCM2}\) as the HTF flows through D-Mannitol (PCM1) and Myristic Acid (PCM2), respectively5,28.

The energy stored in the PCMs, \({E}_{c.PCMs}\) and the system’s charging efficiency, \({\eta }_{charging}\), were calculated using Eqs. (3) and (4), where \({A}_{C}\) represents the collector area and \({I}_{b}\) denotes the solar beam radiation.

To determine the heat release rate from the PCMs during the discharging phase, the flow direction of the heat transfer fluid (HTF) is reversed, allowing it to pass first through PCM2 and then PCM1. The energy release rates for PCM2 (\({Q}_{d.PCM2}\)) and PCM1 (\({Q}_{d.PCM1}\)) are calculated using Eqs. (5) and (6), respectively. Here, \({T}_{d3}\) and \({T}_{d2}\) represent the outlet temperatures of the HTF from PCM tanks 2 and 1, while \({T}_{d1}\) is the inlet temperature of the HTF entering PCM tank 1.

The total energy release from the PCMs, \({E}_{d.PCMs}\), and the discharging efficiency \({\eta }_{discharging}\) of the system are determined using Eqs. (7) and (8).

The result of the energy performance between both the charging and discharging stages determines the system’s total energy effectiveness. Equation (9) is used to express this connection

Results

The experimental and thermo-physical results are analyzed for various types of phase change materials (PCMs), including pure D-Mannitol (Ma), Myristic Acid (My), and their nanoparticle-doped variants: D-Mannitol combined with copper, aluminum, and zinc nanoparticles labeled as Ma-Cu, Ma-Al, and Ma-Zn, respectively; and Myristic Acid combined with the same nanoparticles, referred to as My-Cu, My-Al, and My-Zn.

Effect of thermo-physical properties

Table 1 summarizes the thermo-physical characteristics of the pure materials, such as D-Mannitol, Myristic Acid, and nanoparticles of copper, aluminum, and zinc29. According to Table 1, both D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid exhibit low thermal conductivities of 0.24 and 0.21 W/mK, respectively, but possess relatively high specific heat capacities of 2.4 and 2.0 MJ/m3K. In contrast, copper, aluminum, and zinc nanoparticles have high thermal conductivities but lower specific heat capacities. To improve the thermal conductivity of D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid PCMs, these nanoparticles were incorporated at a concentration of 1.5 wt.% using a two-step synthesis process. The resulting hybrid PCMs-Ma-Cu, Ma-Al, Ma-Zn, My-Cu, My-Al, and My-Zn-demonstrate enhanced thermal conductivity and specific heat capacities, as detailed in Table 2.

All of the hybrid PCM’s volume as well as specific heat interpretations with the original PCM are displayed in Fig. 2. Comparatively speaking, D-Mannitol-Cu and myristic acid-Cu possess greater volumes as well ad particular heat capacities than their parent PCMs. Around the density of these hybrid PCMs rises to 1575 kg/m3 for D-Mannitol-Cu and 890 kg/m3 for Myristic Acid-Cu, compared to 1510 kg/m3 and 860 kg/m3 for the pure forms. Similarly, the specific heat shows a slight variation, maintaining high values close to 2.2–2.3 MJ/m3K for D-Mannitol-Cu and 2.0 MJ/m3K for Myristic Acid-Cu. This increase in density and relatively stable specific heat is attributed to the higher mass density and strong thermal energy absorption capacity of metal nanoparticles. The trend in density and specific heat for D-Mannitol-based PCMs follows Ma-Cu > Ma-Al > Ma-Zn, and similarly for Myristic Acid-based PCMs as My-Cu > My-Al > My-Zn. Figure 3 shows the thermal conductivity and diffusivity performance of all hybrid PCMs in comparison to their parent PCMs. The thermal conductivity of pure D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid is recorded at 0.24 and 0.21 W/m−1 K, respectively, using a standard thermal analyser. After nanoparticle incorporation, there is a noticeable enhancement in thermal conductivity across all hybrid PCMs, with D-Mannitol-Cu reaching up to 0.42 W/m−1 K and Myristic Acid-Cu up to 0.36 W/m−1 K. This increase is driven by the high intrinsic thermal conductivity of metallic nanoparticles, particularly copper. However, among the three metals, Cu-based PCMs show the maximum thermal conductivity enhancement, followed by Al and Zn, thereby establishing the trend: Cu > Al > Zn. The reason for this lies in the thermal conductive nature of the nanoparticles and their ability to form efficient heat pathways within the PCM matrix. Additionally, the thermal diffusivity of hybrid PCMs improves significantly compared to parent PCMs. For instance, D-Mannitol-Cu and Myristic Acid-Cu show increased thermal diffusivity values of 0.25 × 10⁻⁶ m2/s and 0.24 × 10⁻⁶ m2/s, respectively, as compared to 0.18 and 0.17 × 10⁻⁶ m2/s for the pure materials. Thermal diffusivity, which reflects the rate at which a material conducts thermal energy relative to its ability to store it, indicates that Cu-based hybrid PCMs have a faster thermal response and improved energy stability. These results affirm that metal nanoparticle doping significantly enhances the thermal performance of D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid PCMs, with copper nanoparticles offering the most pronounced improvements in conductivity and diffusivity while preserving high specific heat and density for efficient thermal storage18,29,30.

Cycle of powering up and discharging

A charging and discharging procedure is used to conduct the experiment. D-Mannitol-based PCMs are charged for 400 min, while myristic acid-based PCMs are charged for 250 min at 10-min intervals. The charging cycle for D-Mannitol and its hybrid PCMs is depicted in Fig. 4, which reveals that there are no appreciable variations in temperature between the PCMs for up to 70 min. All PCMs exhibit a slow increase in heating after 70 min, which continues until 200 min, when they start to phase transition and initiate passive heat storage. The PCMs mostly participate in the phase change energy storage process between 200 and 300 min; after that, they achieve a stable state with storage of heat. Among the hybrid PCMs, Ma-Zn begins its phase transition earlier compared to other variants such as Ma-Al and Ma-Cu. This behavior can be attributed to the superior thermal conductivity and dispersion characteristics of zinc nanoparticles, which allow more uniform heat distribution within the D-Mannitol matrix, leading to quicker heat absorption and greater latent heat retention. Figure 5 illustrates the discharging cycle of D-Mannitol and its hybrid PCMs, where Ma-Zn demonstrates faster energy release and returns to its initial state more rapidly than the other D-Mannitol-based PCMs. This efficient thermal reversibility is due to zinc’s ability to form stable, thermally conductive pathways throughout the matrix, which enhances the cooling rate and makes Ma-Zn highly suitable for repeated thermal cycling applications5,16.

Figures 6 and 7 display the charging and discharging profiles of Myristic Acid and its hybrid PCMs. During the charging phase shown in Fig. 6, the temperature among all PCMs remains closely aligned up to 30 min. Beyond this, a gradual temperature increase is noted until approximately 100 min, after which phase change initiates. Between 100 and 150 min, the materials undergo the latent heat storage process. Among the hybrids, My-Zn shows an earlier transition into the phase change region compared to My-Al and My-Cu. This is primarily due to the enhanced thermal response and stable distribution of Zn nanoparticles within the Myristic Acid matrix, which not only accelerates the thermal conductivity but also improves energy storage efficiency. The discharging behavior presented in Fig. 7 confirms that My-Zn releases stored heat and reverts to its original phase more quickly than the other Myristic Acid PCMs. This thermal behavior validates the superior performance of My-Zn in thermal cycling, supported by its higher latent heat transfer and better compatibility within the PCM structure, minimizing agglomeration and enhancing consistent heat release5,20.

Heat transfer rate

Figure 8 shows the velocity of heat transfer for D-Mannitol and its hybrid PCMs. The heat gains for Ma, Ma-Cu, Ma-Al, and Ma-Zn are 3435.96 kJ, 3618.27 kJ, 3811.61 kJ, and 3956.40 kJ, respectively. Ma-Zn shows the highest heat gain among these hybrid PCMS in comparison to other hybrid and parent D-Mannitol PCMs. This suggests that Ma-Zn has a higher interfacial contact ratio, and the tendency is also shown in heat loss. Heat gain increases in the following order: Ma < Ma-Cu < Ma-Zn. Thus, among all the PCMs, the Ma-Zn nano hybrid PCM had the greatest tendency to retain heat.

The heat transfer rate of D-Mannitol and its hybrid PCMs is displayed in Fig. 8. Ma, Ma-Cu, Ma-Al, and Ma-Zn have respective heat gains of 3435.96 kJ, 3618.27 kJ, 3811.61 kJ, and 3956.40 kJ. When compared to other hybrid and parent D-Mannitol PCMs, Ma-Zn exhibits the largest heat gain among these hybrid PCMs. This indicates that the interfacial contact ratio is larger for Ma-Zn, and the tendency is also observed in the heat loss. The increasing order of heat gain is Ma < Ma-Cu < Ma-Al < Ma-Zn. Therefore, the Ma-Zn Nano-hybrid PCM has the highest propensity to store thermal energy among all PCMs.

The heat transfer rate of myristic acid and its hybrid PCMs is displayed in Fig. 9. My, My-Cu, My-Al, and My-Zn had respective heat gains of 1061.83 kJ, 1184.76 kJ, 1276.58 kJ, and 1451.51 kJ. In comparison to other hybrid and parent D-Mannitol PCMs, My-Zn exhibits the largest heat gain among these hybrid PCMs. My < My-Cu < My-Al < My-Zn is the rising order of heat gain, indicating that My-Zn has a greater interfacial contact ratio. The heat loss trend follows the same pattern. Thus, the My-Zn Nano-hybrid PCM has the highest propensity to store thermal energy among the PCMs. The nanohybrid PCMs show superior energy storage capacity when compared to the results of thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity, and heat transfer rate. The exceptional energy storage capacity of Ma-Zn and My-Zn nanohybrid PCMs is a result of their high diffusivity and thermal conductivity.

Conclusion

This study successfully synthesized and characterized hybrid nano-phase change materials (nano-PCMs) based on D-Mannitol and Myristic Acid, each doped with copper (Cu), aluminum (Al), and zinc (Zn) nanoparticles at a 1.5 wt.% concentration. The resulting composites-Ma-Cu, Ma-Al, Ma-Zn, My-Cu, My-Al, and My-Zn-demonstrated enhanced thermal conductivity, diffusivity, specific heat, and density, primarily due to improved interfacial heat transfer facilitated by the nanoparticles. Notably, Ma-Cu and My-Cu exhibited the highest thermal conductivities, measuring 0.42 W/mK and 0.36 W/mK, respectively. Performance evaluations highlighted significant enhancements in heat transfer rates, with Ma-Zn and My-Zn reaching maximum values of 3956.40 kJ and 1451.51 kJ. These results emphasize the promising role of hybrid nano-PCMs in improving the efficiency of thermal energy storage systems over a broad temperature range. However, this study was limited by its focus on controlled laboratory conditions and a single nanoparticle loading. Aspects such as long-term thermal stability, compatibility with other system materials, and behavior under repeated thermal cycling remain to be explored in future research.

Future research should focus on scaling up the synthesis process, evaluating the long-term performance and stability of nano-PCMs under real-world operating conditions, exploring different nanoparticle concentrations and combinations, and assessing environmental and economic implications. Additionally, integrating these materials into pilot-scale energy systems will be vital to validate their practical feasibility. Overall, this work contributes to the growing body of knowledge on nano-enhanced PCMs and presents a promising route for developing efficient, multi-temperature thermal energy storage technologies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhao, Y. Co-precipitated Ni/Mn shell coated nano Cu-rich core structure: A phase-field study. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 21, 546–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.09.032 (2022).

Verma, P. & Varun, S. K. Singal, review of mathematical modeling on latent heat thermal energy storage systems using phase-change material. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 12, 999–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2006.11.002 (2008).

Li, T., Merabtine, A., Lachi, M., Martaj, N. & Bennacer, R. Experimental study on the thermal comfort in the room equipped with a radiant floor heating system exposed to direct solar radiation. Energy 230, 120800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120800 (2021).

Asgharian, H. & Baniasadi, E. A review on modeling and simulation of solar energy storage systems based on phase change materials. J. Energy Storage 21, 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2018.11.025 (2019).

Jayaprakash, V., Ganesan, S., Beemkumar, N., Sunil Kumar, M. & Kamakshi Priya, K. Enhancing thermal energy storage efficiency: Synthesis and analysis of hybrid Nano-PCMs. Res. Eng. 26, 104899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104899 (2025).

Selvam, D. C. et al. A comprehensive review on hybrid solar–PCM systems for energy-efficient buildings. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 82, 104562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2025.104562 (2025).

Hinojosa, J. F., Moreno, S. F. & Maytorena, V. M. Low-temperature applications of phase change materials for energy storage: A descriptive review. Energies 16, 3078. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16073078 (2023).

Roget, F., Favotto, C. & Rogez, J. Study of the KNO3–LiNO3 and KNO3–NaNO3–LiNO3 eutectics as phase change materials for thermal storage in a low-temperature solar power plant. Sol. Energy 95, 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2013.06.008 (2013).

Fan, L. & Khodadadi, J. M. An experimental investigation of enhanced thermal conductivity and expedited unidirectional freezing of cyclohexane-based nanoparticle suspensions utilized as nano-enhanced phase change materials (NePCM). Int. J. Therm. Sci. 62, 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2011.11.005 (2012).

Zeng, T. et al. Enhancing energetic disorder in all-organic composite dielectrics for high-temperature capacitive energy storage. Nat. Commun. 16(1), 5620. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60741-1 (2025).

Colangelo, G., Favale, E., de Risi, A. & Laforgia, D. Results of experimental investigations on the heat conductivity of nanofluids based on diathermic oil for high temperature applications. Appl. Energy 97, 828–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.11.026 (2012).

Yu, Z.-T. et al. Increased thermal conductivity of liquid paraffin-based suspensions in the presence of carbon nano-additives of various sizes and shapes. Carbon N. Y. 53, 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2012.10.059 (2013).

Hussain, A.-K.H., Saw, L. C. & Afolabi, L. Review on nanomaterials for thermal energy storage technologies. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Asia 3, 60–71. https://doi.org/10.2174/22113525113119990011 (2013).

Christopher Selvam, D. & Devarajan, Y. Bio-inspired hybrid materials for sustainable energy: Advancing bioresource technology and efficiency. Mater. Today Commun. 46, 112647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2025.112647 (2025).

Huang, Z. et al. Thermal insulation and high-temperature resistant cement-based materials with different pore structure characteristics: Performance and high-temperature testing. J. Build. Eng. 101, 111839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.111839 (2025).

Li, X. et al. D-Mannitol impregnated within surface-roughened hydrophilic metal foam for medium-temperature solar-thermal energy harvesting. Energy Convers. Manag. 222, 113241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113241 (2020).

Anish, R., Mariappan, V., Joybari, M. M. & Abdulateef, A. M. Performance comparison of the thermal behavior of Myristic Acid and D-Mannitol in a double spiral coil latent heat storage system. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 15, 100441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2019.100441 (2020).

Feng, B., Fan, L.-W., Zeng, Y., Ding, J.-Y. & Shao, X.-F. Atomistic insights into the effects of hydrogen bonds on the melting process and heat conduction of D-Mannitol as a promising latent heat storage material. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 146, 106103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2019.106103 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. Enabling high-sensitivity calorimetric flow sensor using vanadium dioxide phase-change material with predictable hysteretic behavior. IEEE Trans. Electron Dev. 72(3), 1360–1367. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2025.3532249 (2025).

Jin, H.-Q., Fan, L.-W., Liu, M.-J., Zhu, Z.-Q. & Yu, Z.-T. A pore-scale visualized study of melting heat transfer of a paraffin wax saturated in a copper foam: Effects of the pore size. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 112, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.04.114 (2017).

Gur, M., Oztop, H. F. & Selimefendigil, F. Analysis of solar underfloor heating system assisted with nano enhanced phase change material for nearly zero energy buildings approach. Renew. Energy 218, 119265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.119265 (2023).

Oztop, H. F., Gurgenc, E. & Gur, M. Thermophysical properties and enhancement behavior of novel B4C-nanoadditive RT35HC nanocomposite phase change materials: Structural, morphological, thermal energy storage and thermal stability. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 272, 112909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2024.112909 (2024).

Oztop, H. F., Bakir, E., Selimefendigil, F., Gur, M. & Coşanay, H. Effects of inclined plate in a channel to control melting of PCM in a body inserted on the bottom wall. Exp. Tech. 47, 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40799-022-00582-5 (2023).

Lohith Kumar, P., Beemkumar, N., Sunil Kumar, M. & Yuvarajan, D. Performance evaluation of a multi-mode drying system with thermal energy storage for high-value agricultural products. J. Energy Storage 123, 116743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2025.116743 (2025).

Gur, M., Gurgenc, E., Cosanay, H. & Oztop, H. F. Novel nano-Y2O3/myristic acid nanocomposite PCM for cooling performances of electronic device with various fin designs. J. Energy Storage 100, 113646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.113646 (2024).

Gurgenc, E., Gur, M., Cosanay, H., Gurgenc, T. & Oztop, H. F. Effects of position of semi-circular body on melting of a novel B4C/RT44HC PCM nanocomposite in a closed space. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 65, 105628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.105628 (2025).

Gur, M., Gurgenc, E., Cosanay, H. & Oztop, H. F. Solar-assisted radiant heating system with nano-B4C enhanced PCM for nearly zero energy buildings. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 65, 105544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.105544 (2025).

Liu, F. et al. Improved thermal performance, frost resistance, and pore structure of cement–based composites by binary modification with mPCMs/nano–SiO2. Energy 332, 137166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2025.137166 (2025).

Owolabi, A. L., Al-Kayiem, H. H. & Baheta, A. T. Nanoadditives induced enhancement of the thermal properties of paraffin-based nanocomposites for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy 135, 644–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2016.06.008 (2016).

Jayaprakash, V., Ganesan, S., Beemkumar, N., Sunil Kumar, M. & Kamakshi Priya, K. Experimental investigation of cascaded thermal energy storage systems using finned encapsulated phase change materials. Res. Eng. 25, 104395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104395 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have equally contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No Animals were used/handled in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jayaprakash, V., Ganesan, S., Beemkumar, N. et al. Improving the efficiency of thermal energy storage through the development and evaluation of hybrid nano-enhanced phase change materials. Sci Rep 15, 40415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09214-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09214-5