Abstract

Accurate medical image diagnosis is essential in clinical practice and places high demands on the diagnostic skills of imaging professionals. However, a significant shortage of radiologists highlights the gap between supply and demand, leading to the importance of education. Traditional education has largely neglected the development of visual perception skills, which play a critical role in lesion detection. This study aims to investigate visual training methods that can effectively enhance learners’ perceptual abilities in medical image interpretation through a pre-post experiment. In the experiment, the participants of intervention groups underwent intensive training targeting uncovered visual areas under central or peripheral vision occlusion conditions. The result showed that peripheral vision training significantly improved participants’ diagnostic mean accuracy (from 59.5 to 68.0%, p < 0.001), mean sensitivity (from 69.0 to 79.5%, p < 0.001), mean positive predictive value (from 65.6 to 82.9%, p < 0.001), and reduced mean task time (from 1163.4s to 877.3s, p < 0.001). However, neither peripheral nor central vision training significantly improved specificity and negative predictive value, which were metrics of negative diagnostic ability. Consequently, enhancing peripheral vision perception helped to reduce missed diagnoses, but with limited impact on reducing misdiagnosis. The peripheral training enhanced the effectiveness of medical image diagnosis education to provide competent professionals in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Improving the accuracy of medical image diagnosis is essential for enhancing the quality of patient care1. Specifically, missed diagnoses may delay timely treatment, while misdiagnoses could result in unnecessary medical interventions and emotional anxiety2. As a result, the demands placed on radiology professionals are exceedingly rigorous. However, with advances in medical technology and an aging population, the shortage of radiology professionals has become increasingly severe. For instance, the United Kingdom will face a 44% shortfall in its radiology workforce by 20253, leading to the importance of effective medical image diagnosis education.

Traditional medical image education currently lacks a universal consensus, with significant variation in approaches globally4. It can primarily be categorized into two main components: theoretical knowledge acquisition and practical application5. The theoretical educational approach is often passive, with learners primarily absorbing knowledge through large classroom lectures, which results in limited instructional time and contributes to monotonous and inefficient knowledge delivery6. On the practical side, traditional education often relies on brief on-site hospital practice, but the limited availability of equipment and mentors results in suboptimal practical training outcomes7. Beyond these practice ways, it is challenging for learners to find other suitable practical training, whether provided by the institution or pursued independently8. Visual ability enhancement is essential in improving lesion detection performance in medical imaging9, but is commonly overlooked in traditional education. For future educational strategies, visual perceptual training is crucial for enhancing image diagnosis skills5. Visual perceptual training includes occluding the amblyopic eye, multitasking, retrieving rapidly moving targets, and training in environments characterized by flashing color filters or low contrast10. Visual perceptual training has been extensively validated to improve the visual perceptual skills of trainees in amblyopia rehabilitation11. In amblyopia rehabilitation, repeated visual perceptual training can significantly enhance the visual system’s sensitivity, particularly when processing fundamental visual features such as spatial location and global direction12. Improving visual sensitivity is critical in medical image diagnosis, which heavily depends on efficient visual information retrieval. Lesion detection serves as the initial step in the diagnostic process. After a rapid visual search to locate potential abnormalities, more detailed analysis and interpretation follow. However, visual perceptual training has been minimally applied to the development of lesion detection skills.

In lesion detection process, visual perception involves the integration of central and peripheral vision13which is closely related to the medical image diagnosis performance14. Therefore, perceptual training targeting central and peripheral vision could benefit medical image diagnosis education. Peripheral vision refers to the ability to perceive visual stimuli outside the central retina, and central vision is the opposite15. Central vision exhibits high resolution and is suited for processing detailed information, while peripheral vision exhibits low resolution and perceives information quickly16. The peripheral vision identifies potential areas of abnormality by rapidly scanning the entire image to capture and process global information, providing directional guidance to the central vision17. Then, the central vision precisely captures the details of the regions of interest (ROI)18. Central vision and peripheral vision serve distinct yet complementary roles in lesion detection process, which implies that improvements in each type of vision through perceptual training may have varying effects on overall lesion detection performance.

Visual perceptual abilities are closely linked to lesion detection performance, and perceptual training has been widely applied in other medical fields, such as visual rehabilitation (e.g., treatment of amblyopia and strabismus) and cognitive rehabilitation (e.g., enhancement of attention and spatial skills). However, visual perceptual training in lesion detection skills training remains limited. Furthermore, central and peripheral vision have been recognized for their unique and essential roles in medical image diagnosis. Despite this, previous research on central and peripheral vision remains theoretical and has yet to be effectively applied to improve diagnostic performance in medical imaging. Therefore, this study investigated whether targeted training in peripheral and central vision can improve learners’ diagnostic abilities in medical imaging. Two training methods were designed: central vision training (conducted under conditions where peripheral vision is occluded) and peripheral vision training (conducted under conditions where central vision is occluded). To achieve the study’s aim, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Peripheral vision training improves the lesion detection performance in medical imaging.

H2: Central vision training improves the lesion detection performance in medical imaging.

Materials and methods

Experiment design

This study employed a 3 × 2 mixed design, with training type (full vision, peripheral vision, and central vision training) as the between-subject factor and time (pre-training and post-training) as the within-subject factor, as presented in Table 1. The design aimed to investigate the effects of different training conditions on participants’ performance and to evaluate the changes over time. The experiment procedure is shown in Fig. 1. At the start of the experiment, all participants took a pre-test under full vision conditions. Each test consisted of 40 true/false questions, covering 20 disease cases and 20 healthy cases. The order of the questions was randomized. Participants were informed of only the total number of questions but were not told the ratio of disease to healthy cases. After the pre-test, participants were randomly divided into three groups, each receiving a different training type. Research has shown that about a week of learning is sufficient to induce synaptic consolidation and neural plasticity, while short intervals between sessions help reactivate memory traces and promote systems-level consolidation19,20,21. Therefore, in this study, the training spanned 12 days, with 5 days dedicated to training, 2 days for rest, followed by another 5 days of training.

The group trained under full vision conditions was called the control group. The group receiving peripheral vision training was referred to as Intervention Group (1) They were trained with their central vision occluded to restrict their focus to peripheral vision. The group receiving central vision training was referred to as Intervention Group (2) They were trained with their peripheral vision occluded, ensuring only central vision was utilized during the training process. The participants of intervention groups were required to learn 60 medical image cases (30 disease cases and 30 healthy cases, with correct answers given) per day as daily training. The control group underwent the same case learning without visual occlusion. After the training, participants took a post-test, the same as the pre-test.

The experiment recorded primary and composite diagnostic performance measures, with a total of 10 measures, as shown in Table 2. The primary measures included true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN). These measures were considered essential diagnostic indicators in the medical field22. TP refers to the number of cases correctly identified by the diagnostic test as positive when the patient has the disease. FP indicates the number of cases diagnosed as positive by the test when the patient is healthy. TN represents the number of cases correctly identified as negative when the patient is healthy. FN refers to the number of cases incorrectly identified as negative by the diagnostic test when the patient has the disease23.

The composite measures included accuracy, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV), specificity, and negative predictive value (NPV), which were more widely used to comprehensively assess diagnostic performance because they transform primary measures into more comprehensive metrics through interrelations and calculations24. The composite measures were divided into three sections, as shown in Table 2: the first section was overall diagnostic performance, which included accuracy and task time. Accuracy is the proportion of correctly diagnosed samples to the total number of samples22. Task time reflects the speed of information processing. Longer task times indicate slower processing speeds. The second section of the measures focused on positive diagnostic performance, which reflects missed diagnoses, including sensitivity and PPV24. Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of true positive cases out of all the actual positive cases22. PPV measures the proportion of true positive cases among all cases predicted as positive24. The third section focused on negative diagnostic performance, which also reflects misdiagnoses, including specificity and NPV24. Specificity is defined as the proportion of true negative cases out of all the actual negative cases22. NPV measures the proportion of true negative cases among all cases predicted as negative24. It is important to note that while PPV and NPV may be influenced by disease prevalence in real clinical situations, the prevalence in this study was intentionally balanced at 50% throughout all stages. This approach was designed to provide sufficient exposure to both positive and negative cases, reinforcing students’ ability to identify and exclude abnormalities. The PPV and NPV in this context serve as relative, within-subject indicators of diagnostic improvement under controlled conditions.

Apparatus

This study used tuberculosis cases for detection training due to their characteristic radiological features and established educational value in medical imaging25. The underlying logic of enhancing perceptual sensitivity through visual segmentation can be extended to the learning of other similar cases simply by replacing the training dataset with condition-specific case libraries. All imaging materials used in this study were sourced from multiple open databases, including the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, and relevant GitHub repositories26,27,28. Images with insufficient or excessive penetration were excluded during the data cleaning process to ensure the clarity and quality of the materials. Additionally, to ensure consistency, accessibility, and compatibility across various display devices, all images were standardized to a resolution of 1080 × 1080 pixels. Prior research has shown that the resolution is sufficient to support medical image-based perceptual learning tasks, including on liquid crystal displays (LCDs), cathode ray tube displays (CRTs), virtual reality (VR) devices, or standard computer display monitors (CDMs)29,30,31,32.

The participants’ training and tests were conducted on two web-based platforms. The experiment used standardized 24-inch monitors with a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels for the training and tests. The training platform utilized eye-tracking technology to achieve real-time occlusion of specific visual fields. Specifically, GazePointer software was employed with a standard webcam for eye tracking and mouse control. In a review of 16 different webcam-based eye-tracking software, GazePointer demonstrated an accuracy of 1.43 degrees33.

To achieve real-time occlusion of peripheral or central vision, this study designed two types of masks: one for occluding central vision and one for occluding peripheral vision. The central vision occlusion mask consisted of a black circular patch positioned at the center, the circular occlusion area with a radius of 400 pixels. The feathering value was set to 100 pixels. Feathering was applied to prevent harsh edges that could create noticeable dividing lines in the visual field, thus minimizing unnecessary visual interference. In contrast, the peripheral vision occlusion mask consisted of a transparent circular hole at the center, with the same parameters as the central vision occlusion mask (Fig. 2). The center of the mask was linked to the coordinates of the mouse cursor through programming, with the cursor movement being controlled by GazePointer (Fig. 3). This design ensured that, regardless of the direction of eye movement, the system could occlude the specified visual area. In a pre-experiment, participants were exposed to six gradient versions of the mask, with opacities ranging from 50 to 100%. The results indicated that participants experienced significant discomfort when the opacity exceeded 80%. As a result, the mask opacity was set to 80% to balance optimal visual occlusion with minimal discomfort.

Additionally, a test platform was built to record 10 measures representing participants’ performance in diagnosing the disease status of 40 cases (Fig. 4). Specifically, participants first selected the pre-test or post-test sections on the homepage. Each section consisted of 40 medical image cases. Once the participant clicked on the button for either the pre-test or post-test section, the system began timing, and medical images were displayed on the screen in a random sequence. The question number was shown in the top-left corner of the screen. If the participant determined the case to be positive, they clicked the red button; otherwise, they clicked the green button. After making a selection, participants were not able to modify their answers. Upon completing the 40th question, the timer stopped, and the test results including the 10 measures were recorded but not shown to the participants.

Participants

A total of 30 participants were recruited, including 15 females and 15 males (mean age = 23.6 years). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) undergraduate medical imaging students, who had received foundational training in anatomy and medical imaging interpretation as part of their curriculum, (b) having a normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and (c) having completed a preliminary test before the formal experiment with an accuracy rate between 50% and 70%. The accuracy rate indicated significant potential for improvement in their diagnostic ability. The procedure for the test was the same as the formal test, but with different questions. The exclusion criteria were: (a) with neurological disorders or cognitive dysfunction, (b) unable to commit to persist with a 12-day training, and (c) with a history of significant visual impairments or conditions that could interfere with the task. Participants received monetary compensation (approximately 5 USD) for their participation. The experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Research Committee of the South China University of Technology.

Procedure

First, the researchers provided detailed explanations about the arrangement of the study, the experimental process, and information security measures. Participants were informed that their eye movement data would be used during the experiment but assured that only test results would be recorded and no video or other personal data would be captured. All data would be used exclusively for research analysis purposes. Participants voluntarily signed a consent agreement. All participants first completed the pre-test without any training. Before the test, the researchers demonstrated the operation of the test platform. Participants were given five minutes to familiarize themselves with the platform using practice questions. After that, the pre-test was conducted. Upon completion, the researchers recorded each participant’s results for archiving. The training began the following day. The researchers set up multiple lighting fixtures in the experimental area to ensure adequate ambient illumination, enhancing eye-tracking data accuracy. Researchers individually calibrated each participant’s gaze points. Once all preparations were complete, the researchers left the area to provide a quiet environment conducive to learning. During the training, participants could call for assistance from researchers stationed outside the room if they had operational questions or experienced physical discomfort. After all training, the participants received a monetary reward for their effort. The post-test followed the same procedure as the pre-test and was conducted on the first day after the training concluded. This scheduling aimed to minimize the potential for knowledge decay due to rest, ensuring an accurate assessment of participants’ learning outcomes.

Result

Overall diagnostic performance

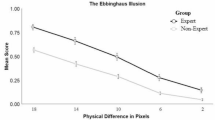

Accuracy: The accuracy in the post-test differed significantly across groups [F (2, 27) = 10.764, p < 0.001, η² = 0.444)]. Further pairwise comparisons revealed that in post-test, only the accuracy of the peripheral vision training group (Mean = 0.680, SD = 0.066) was significantly higher than the control group (Mean = 0.581, SD = 0.046), with p = 0.001, 95% CI = [0.039, 0.159], and also showed a significant improvement compared to pre-test (Mean = 0.595, SD = 0.034), with p = 0.001, 95% CI = [0.037, 0.133] (Fig. 5a; Table 3).

Task time: The task time in the post-test differed significantly across groups [F (2, 27) = 9.596, p < 0.001, η² = 0.415]. Further pairwise comparisons revealed that in the post-test, only the task time of the peripheral vision training group (Mean = 877.3, SD = 163.0) was significantly shorter than the control group (Mean = 1102.2, SD = 166.1), p = 0.021, 95% CI = [−421.0, −28.8], and also showed a significant reduce compared to pre-test (Mean = 1163.4, SD = 228.7), p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−361.3, −210.9] (Fig. 5b).

Pairwise comparisons of pre- and post-test diagnostic performance across different groups (error bars represent standard deviations): (a) accuracy comparison; (b) task time comparison. (a) and (b) represented the overall diagnostic performance. (c) Sensitivity comparison; (d) Positive predictive value (PPV) comparison. (c) and (d) represented positive diagnostic performance. (e) Specificity comparison; (f) Negative predictive value (NPV) comparison. (e) and (f) represented negative diagnostic performance. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Positive diagnostic performance

Sensitivity: The sensitivity in the post-test was not significantly different across groups [F (2, 27) = 2.54, p = 0.098, η² = 0.158]. However, the interaction effect between group and time was significant [F (2, 27) = 5.239, p = 0.012, η² = 0.280], indicating that the improvement in sensitivity from pre-test to post-test differs significantly across groups. Further pairwise comparisons revealed that in the post-test, only the sensitivity of the peripheral vision training group (Mean = 0.795, SD = 0.072) showed a significant improvement compared to the pre-test (Mean = 0.690, SD = 0.077), p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.055, 0.155] (Fig. 5c).

Positive predictive value (PPV): The PPV in the post-test differed significantly across groups [F (2, 27) = 5.774, p = 0.008, η² = 0.300]. Further pairwise comparisons revealed that, in post-test, only the PPV of the peripheral vision training group (Mean = 0.829, SD = 0.105) significantly higher than the control group (Mean = 0.720, SD = 0.080), p = 0.046, 95% CI = [0.002, 0.216], and also showed a significant improvement compared to pre-test (Mean = 0.656, SD = 0.094), p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.101, 0.245] (Fig. 5d).

Negative diagnostic performance

Specificity: The specificity in the post-test was not significantly different across groups, [F (2, 27) = 2.296, p = 0.120, η² = 0.145]. It was also noteworthy that in the pre-test, the specificity (Mean = 0.482, SD = 0.147) was significantly lower than the sensitivity (Mean = 0.698, SD = 0.080), t (29) = −5.656, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −1.032, 95% CI = [−0.295, −0.138] (Fig. 5e).

Negative predictive value (NPV): The NPV in the post-test was not significantly different across groups, [F (2, 27) = 2.212, p = 0.129, η² = 0.141]. It was also noteworthy that in the pre-test, the NPV (Mean = 0.518, SD = 0.162) was significantly lower than the PPV (Mean = 0.671, SD = 0.099), p = 0.002, t (29) = −3.403, Cohen’s d = −0.621, 95% CI = [−0.245, −0.061] (Fig. 5f).

Discussion

Overall diagnostic performance

Peripheral vision training significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy, emphasizing the critical role of peripheral vision in improving diagnostic performance, confirming Hypothesis 1. When central vision was restricted, peripheral vision took on a significant visual load, performing tasks typically handled by central and peripheral vision. This training approach resembles visual rehabilitation techniques, such as monocular occlusion therapy34. The uncovered amblyopic eye or visual field can gradually improve under intensive training, narrowing the gap in visual ability with the occluded region. This principle of training through increased cognitive load is widely applied in the field of education35. Increasing germane cognitive load can improve information processing and memory consolidation, leading to robust cognitive frameworks36. In this experiment, peripheral vision improved information retrieval ability under increased cognitive load. This improvement helped practitioners efficiently gather critical information before making cognitive judgments, laying a solid foundation for diagnostic decisions and ensuring that important details were not overlooked37.

The improvement in diagnostic performance may be attributed to peripheral vision training, which suppressed irrelevant stimuli, thereby reducing the cognitive load on working memory. In medical image diagnosis, working memory and long-term memory interact closely, with working memory as a limited resource. The ultimate goal of learning is to enhance long-term memory, which can be achieved by reducing the burden on working memory35. By refining the peripheral vision, medical professionals can improve their selective attention, enabling them to filter out non-critical information more effectively38. This suppression of irrelevant stimuli can be understood as an enhancement of the filtering ability of peripheral vision, which reduces visual crowding effects, thereby optimizing information processing, improving categorization, and actively suppressing distractions39. This reduction in cognitive load frees up space in working memory for more efficient processing of new information. Accordingly, the experimental results demonstrated that peripheral vision training significantly reduced task completion time, accelerated information processing, and improved diagnostic efficiency.

In contrast to peripheral vision training, central vision training did not significantly improve diagnostic accuracy or task time, thereby disproving Hypothesis 2. This could be explained by the differing potential for improvement of the two types of vision when exposed to the same level of training intensity. Central vision was frequently used in daily life, so the improvement of central vision training was less noticeable. It is widely recognized in cognitive science that the improvement of certain abilities often exhibits a phenomenon of diminishing returns: initial gains are typically substantial, but as proficiency increases, the marginal benefits of further improvement decrease40. This effect is particularly evident as individuals gain more experience and expertise in specific cognitive tasks, making further advancements increasingly difficult41. Therefore, there could be a nonlinear relationship between additional improvements in central vision and training, resulting in diminishing returns for overall diagnostic ability. More targeted training methods may be required to optimize the role of central vision in the diagnostic process. This effect also highlighted that peripheral vision training can more efficiently enhance overall diagnostic ability compared to central vision training.

Positive diagnostic performance

In peripheral vision training, significant improvements were observed in sensitivity and PPV, supporting the validity of Hypothesis 1 regarding the perception of positive cases. Sensitivity and PPV reflect a clinician’s or model’s ability to detect positive cases42which fundamentally requires distinguishing the tiny abnormal features. Detecting such features demands broad, initial processing, where peripheral vision is critical. Peripheral vision enables the detection of subtle changes by performing an exploratory search across the image. This perceptual process is geared towards detecting different, often overlooked details within a wide field of view which is particularly crucial for identifying positive cases, where abnormalities are typically small, localized, and rare compared to the majority of the image9. The expansive search capabilities of peripheral vision increase the likelihood of detecting these suspicious features early in the process, identifying potential areas of concern that may require further detailed examination42. Therefore, enhancing peripheral vision can significantly improve the detection capability of positive cases.

Unlike peripheral vision training, central vision training did not significantly improve participants’ ability to detect positive cases, failing to support Hypothesis 2. This phenomenon may have been attributed not only to the diminishing returns effect but also to the different roles and functions of peripheral and central vision in detecting positive cases. Determining whether a patient was positive was fundamentally a binary classification decision43. Identifying a lesion during visual research is sufficient to classify a case as positive, indicating the presence of disease, without requiring further assessment of the lesion’s extent, number, or severity. It does not equate to a comprehensive medical diagnostic workflow. The task of figuring out the positive cases is a goal-directed information retrieval activity44where the ability to detect differences is crucial and may have outweighed the importance of detailed observation. In this process, clinicians employ saccadic eye movements to scan a wide area, searching for suspicious regions that deviate from their prior knowledge17. The scanning behavior rely heavily on peripheral vision’s rapid detection and localization capabilities, while central vision becomes engaged later in magnifying details through fixation15. It is sufficient for experienced clinicians to find a lot of information during the quick scanning45. Therefore, in the binary decision, rapidly detecting abnormalities could be more critical than the ability to discern fine details. This phenomenon also has parallels in non-medical contexts, which demonstrated exceptional classification and rapid decision-making capabilities, sometimes within 50 milliseconds46. Studies showed that peripheral vision can quickly detect objects with rapid movement from any side of the car during driving47track high contrast, high light things48and distinguish colors during visual exploration49or identify facial emotions of other people50. In these scenarios, the central vision primarily served a supplementary or supportive role without needing in-depth engagement51.

Although peripheral vision is crucial in specific tasks, humans rely on central vision in everyday life more often. Peripheral vision remains relatively weak and underdeveloped. According to the weakest link hypothesis, when two effect elements are interdependent, prioritizing the improvement of weaker components is generally more effective in enhancing overall performance52. For example, in visual rehabilitation practices, training often focuses on improving the weaker eye rather than further strengthening the dominant eye, aiming to achieve more balanced visual capabilities53. This balancing strategy may have explained why peripheral vision training, in the short term, yielded more significant improvements in diagnostic performance compared to central vision training. However, the findings of this study did not imply that central vision training was irrelevant to lesion detection. The study highlighted that peripheral vision training was more effective in enhancing performance in the specific task of binary decision-making regarding the presence of disease under equal training intensity than central vision training.

Negative diagnostic performance

In this study, neither peripheral nor central vision training significantly improved participants’ ability to identify negative cases, which indicated that the misdiagnosis rate did not decrease with training. These results suggested that while Hypothesis 1 supported improved missed diagnoses, it may not have fully applied to improve misdiagnoses. Hypothesis 2 was still not validated. This result could be attributed to the fact that misdiagnosis was not only linked to the visual retrieval process but also closely associated with errors in the subsequent cognitive judgment stage54. Misdiagnosis typically occurs when suspicious or misleading areas appear in medical images. Clinicians may misinterpret these areas due to attribution errors, especially when the suspicious lesions resemble surrounding normal tissue or other types of pathology9. For example, benign tumors may appear similar to malignant tumors, and inflammatory lesions may be mistaken for tumors due to their similar imaging characteristics55. Such misjudgments typically occur after peripheral vision has completed the initial detection of the suspicious area and the cognitive judgment stage is entered56. Once a suspicious area has been identified by vision, further profound observation depends on the cognitive guidance provided by the clinicians57. At this stage, the clinicians use their knowledge and experience to decide which details to focus on to verify the initial judgment or make further checks58. However, if the clinician lacks sufficient knowledge, they may not have a clear cognitive framework to guide their visual search, leading to uncertainty about which details are worth focusing on and potentially making incorrect decisions. Therefore, misdiagnosis is closely linked to the cognitive judgment process, particularly in how clinicians select key features within suspicious areas to support their final diagnosis.

Furthermore, the study observed that participants’ performance in diagnosing negative cases was significantly lower than in diagnosing positive cases. The results suggested that misdiagnosis was more prevalent than missed diagnosis among the participants. This difference may be related to psychological factors59. These mistakes are conscious but unavoidable60. In medical diagnosis, especially in high-stakes clinical decision-making, clinicians tend to prioritize avoiding missed diagnoses, as the consequences of a missed diagnosis are generally more severe than those of a misdiagnosis1. In clinical practice, a missed diagnosis may mean missing optimal treatment opportunities, potentially leading to worsened health outcomes or death. In contrast, misdiagnosis can often be corrected through further investigation or treatment. To avoid the risks of missing a diagnosis, clinicians may err on caution, leading to overdiagnosis. This overdiagnosis behavior is particularly common in certain screening contexts and is influenced by societal norms and legal pressures2. This psychological phenomenon aligns with prospect theory, which posits that individuals are generally more averse to losses than motivated by equivalent gains61. When faced with an uncertain case, physicians tend to evaluate the potential consequences of an incorrect judgment. Driven by loss aversion and risk avoidance, they were more likely to classify uncertain cases as positive cases, thereby increasing the probability of false positives.

This study further found that the participants tended to classify images as positive cases. The proportion of samples predicted as negative out of the total samples (Mean = 0.473, SD = 0.065) was significantly lower than the proportion of samples predicted as positive (Mean = 0.527, SD = 0.065), p = 0.033, t (29) =−2.237, Cohen’s d = −0.405, 95% CI = (−0.102, −0.005). In conclusion, future research should explore how to improve psychological factors and develop targeted educational or training methods to reduce misdiagnosis behaviors, ultimately improving the accuracy of diagnosing negative cases.

Implementation cost

Eye-tracking is the most significant hardware requirement for the proposed training. The training method used standard webcams instead of expensive research-grade eye trackers. Since the training focuses on enhancing visual sensitivity through increased perceptual load rather than requiring precise gaze measurements. As a result, webcam-based gaze tracking is sufficient and widely accessible. In addition, the system is deployed via a web-based platform, which ensures strong cross-device compatibility and reduces development and maintenance costs. Institutions can integrate the system with minimal IT infrastructure, and students can access training on personal devices without specialized hardware. In terms of human resource costs, the platform is designed for autonomous use. Once integrated into a curriculum, it requires minimal ongoing input from instructors. Students engage in self-paced learning, with flexible scheduling that minimizes disruption to existing coursework. Overall, the training method achieves a balance between effectiveness and feasibility, making it suitable for widespread adoption in diverse educational settings.

Study limitation

First, while peripheral vision training showed positive effects, its potential negative aspects, such as the crowding effect62the distraction from excessive peripheral stimuli were not independently examined. Additionally, this study focused on medical imaging students. The applicability of the proposed training to experienced professionals remains unknown. The sample size was relatively modest, though post-hoc analysis confirmed sufficient statistical power for the primary outcomes. Moreover, this study validated the training using tuberculosis cases within an experimental context, without extending to other pathologies or real classroom environments. Future research should incorporate a broader range of pathologies to meet the diverse training needs of students from various specialties. Last, while this study confirmed the effectiveness of the proposed training, the training has not yet been fully implemented in practical classroom settings, with validation conducted primarily in an experimental context.

Future work

This study focused primarily on early-stage abnormality detection. Future research could extend this work to include training in lesion classification and higher-order diagnostic interpretation skills. Additionally, the lack of a significant impact on misdiagnosis rates observed in this study may be influenced by psychological factors, such as loss aversion and risk sensitivity, as described in prospect theory61which could be considered in the design of future training paradigms. Moreover, investigating learning and retention curves may offer insights into the progression and sustainability of perceptual improvements over time. Further exploration is also warranted into the effects of other forms of visual interference in medical imaging, such as low contrast, underexposure, and color inversion, to simulate real-world diagnostic challenges. These directions provide a valuable foundation for advancing perceptual training strategies in medical image education.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that peripheral vision training significantly improved diagnostic performance, primarily by reducing missed diagnoses, with no significant impact on misdiagnoses. In contrast, central vision training had no significant effect on either. These findings underscored the critical role of peripheral vision in information retrieval and highlighted its potential as an effective training tool for lesion detection, with valuable implications for medical imaging diagnosis education.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this article are not publicly available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ssman6@scut.edu.cn.

References

Vally, Z. I. et al. Errors in clinical diagnosis: a narrative review. J. Int. Med. Res. 51 https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605231162798 (2023).

Cantey, C. The practice of medicine: Understanding diagnostic error. J. Nurse Practitioners. 16, 582–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.05.014 (2020).

Zhong, J. et al. Attracting the next generation of radiologists: a statement by the European society of radiology (ESR). Insights into Imaging. 13, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-022-01221-8 (2022).

Awan, O. A. Analysis of common innovative teaching methods used by radiology educators. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 51, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2020.12.001 (2022).

Wade, S. W. T., Velan, G. M., Tedla, N., Briggs, N. & Moscova, M. What works in radiology education for medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 24, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04981-z (2024).

Shu, L., Bahri, F., Mostaghni, N., Yu, G. & Javan, R. The time has come: a paradigm shift in diagnostic radiology education via simulation training. J. Digit. Imaging. 34, 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-020-00405-2 (2021).

Recker, F. et al. Exploring the dynamics of ultrasound training in medical education: current trends, debates, and approaches to didactics and hands-on learning. BMC Med. Educ. 24, 1311. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06092-9 (2024).

Fromke, E. J., Jordan, S. G. & Awan, O. A. Case-based learning: its importance in medical student education. Acad. Radiol. 29, 1284–1286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2021.09.028 (2022).

Krupinski, E. A. Current perspectives in medical image perception. Atten. Percept. Psychophysics. 72, 1205–1217. https://doi.org/10.3758/app.72.5.1205 (2010).

Trauzettel-Klosinski, S. Current methods of visual rehabilitation. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int. 108, 871–878. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2011.0871 (2011).

Lu, Z. L. & Dosher, B. A. Current directions in visual perceptual learning. Nat. Reviews Psychol. 1, 654–668. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00107-2 (2022).

Sagi, D. Perceptual learning in vision research. Vision. Res. 51, 1552–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2010.10.019 (2011).

Drew, T., Evans, K., Võ, M. L., Jacobson, F. L. & Wolfe, J. M. Informatics in radiology: what can you see in a single glance and how might this guide visual search in medical images? Radiographics: Rev. Publication Radiological Soc. North. Am. Inc. 33, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.331125023 (2013).

Apelt, D. et al. in Conference on Medical Imaging - Image Perception, Observer Performance, and Technology Assessment. (2009).

Stewart, E. E. M., Valsecchi, M. & Schütz A. C. A review of interactions between peripheral and foveal vision. J Vision 20 (2020).

Strasburger, H., Rentschler, I. & Jüttner, M. Peripheral vision and pattern recognition: a review. J. Vis. 11 5, 13 (2011).

Hättenschwiler, N., Merks, S., Sterchi, Y. & Schwaninger, A. Traditional visual search vs. X-Ray image inspection in students and professionals: are the same visual-Cognitive abilities needed?? Frontiers Psychology 10 (2019).

Peyrin, C. et al. Semantic and physical properties of peripheral vision are used for scene categorization in central vision. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 33, 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01689 (2021).

Ditye, T. et al. Rapid changes in brain structure predict improvements induced by perceptual learning. NeuroImage 81, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.058 (2013).

Frank, S. M., Reavis, E. A., Tse, P. U. & Greenlee, M. W. Neural mechanisms of feature conjunction learning: enduring changes in occipital cortex after a week of training. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 35, 1201–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22245 (2014).

Dudai, Y., Karni, A. & Born, J. The consolidation and transformation of memory. Neuron 88, 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.004 (2015).

Akobeng, A. K. Understanding diagnostic tests 1: sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway:) 96, 338–341, ) 96, 338–341, (1992). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00180.x (2007).

Monaghan, T. F. et al. Foundational statistical principles in medical research: A tutorial on odds ratios, relative risk, absolute risk, and number needed to treat. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115669 (2021).

Trevethan, R., Sensitivity, Specificity & Values, P. Foundations, pliabilities, and pitfalls in research and practice. Front. Public. Health. 5, 307. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00307 (2017).

Yayan, J., Franke, K. J., Berger, M., Windisch, W. & Rasche, K. Early detection of tuberculosis: a systematic review. Pneumonia 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-024-00133-z (2024).

Rahman, T. et al. Reliable tuberculosis detection using chest X-Ray with deep learning, segmentation and visualization. IEEE Access. 8, 191586–191601. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3031384 (2020).

Jaeger, S. et al. Automatic tuberculosis screening using chest radiographs. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 33, 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2013.2284099 (2014).

Candemir, S. et al. Lung segmentation in chest radiographs using anatomical atlases with nonrigid registration. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 33, 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2013.2290491 (2014).

England, A. et al. A comparison of perceived image quality between computer display monitors and augmented reality smart glasses. Radiography 29, 641–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2023.04.010 (2023).

Samei, E. et al. Assessment of display performance for medical imaging systems: executive summary of AAPM TG18 report. Med. Phys. 32, 1205–1225. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.1861159 (2005).

Bhargava, P. et al. Radiology education 2.0—On the cusp of change: part 1. Tablet computers, online curriculums, remote meeting tools and audience response systems. Acad. Radiol. 20, 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2012.11.002 (2013).

Li, C. H. et al. Virtual Read-Out: radiology education for the 21st century during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad. Radiol. 27, 872–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2020.04.028 (2020).

Heck, M., Becker, C. & Deutscher, V. K. in Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Sen, S., Singh, P. & Saxena, R. Management of amblyopia in pediatric patients: current insights. Eye (London England). 36, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01669-w (2022).

Hery Murtianto, Y. & Agus Herlambang, B. & Muhtarom. Cognitive load theory on virtual mathematics laboratory: systematic literature review. KnE Social Sciences (2022).

Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Education Tech. Research Dev. 68, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09701-3 (2020).

Lévêque, L., Bosmans, H., Cockmartin, L. & Liu, H. State of the art: Eye-Tracking studies in medical imaging. IEEE Access. 6, 37023–37034. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2851451 (2018).

Ryu, D., Abernethy, B., Mann, D. L., Poolton, J. M. & Gorman, A. D. The role of central and peripheral vision in expert decision making. Perception 42, 591–607. https://doi.org/10.1068/p7487 (2013).

Yu, D. Training peripheral vision to read: using stimulus exposure and identity priming. Percept. Sci. 16 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.916447 (2022).

Blum, D. & Holling, H. Spearman’s law of diminishing returns. A meta-analysis. Intelligence 65, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2017.07.004 (2017).

Marris, J. E. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of different perceptual training methods in a difficult visual discrimination task with ultrasound images. Cogn. Research: Principles Implications. 8, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-023-00467-0 (2023).

Nuthmann, A. How do the regions of the visual field contribute to object search in real-world scenes? Evidence from eye movements. J. Experimental Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 40 (1), 342–360 (2014).

Gutowski, N., Schang, D., Camp, O. & Abraham, P. A novel multi-objective medical feature selection compass method for binary classification. Artif. Intell. Med. 127, 102277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2022.102277 (2022).

Markonis, D. et al. User-oriented evaluation of a medical image retrieval system for radiologists. Int. J. Med. Informatics. 84, 774–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.04.003 (2015).

Kim, Y. W. & Mansfield, L. T. Fool me twice: delayed diagnoses in radiology with emphasis on perpetuated errors. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 202, 465–470. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.13.11493 (2014).

Greene, M. R. & Oliva, A. Recognition of natural scenes from global properties: seeing the forest without representing the trees. Cogn. Psychol. 58, 137–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2008.06.001 (2009).

Wolfe, B., Dobres, J., Rosenholtz, R. & Reimer, B. More than the useful field: considering peripheral vision in driving. Appl. Ergon. 65, 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.07.009 (2017).

Amano, K. & H Foster, D. Influence of local scene color on fixation position in visual search. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 31, A254–262. https://doi.org/10.1364/josaa.31.00a254 (2014).

Nuthmann, A. & Malcolm, G. L. Eye guidance during real-world scene search: the role color plays in central and peripheral vision. J. Vis. 16 https://doi.org/10.1167/16.2.3 (2016).

Rigoulot, S. et al. Fearful faces impact in peripheral vision: behavioral and neural evidence. Neuropsychologia 49, 2013–2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.03.031 (2011).

Boucart, M., Moroni, C., Thibaut, M., Szaffarczyk, S. & Greene, M. R. Scene categorization at large visual eccentricities. Vis. Res. 86, 35–42 (2013).

Tol, R. S. J. & Yohe, G. W. The weakest link hypothesis for adaptive capacity: an empirical test. Glob. Environ. Change. 17, 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.08.001 (2007).

Hernández-Rodríguez, C. J. et al. Stimuli characteristics and psychophysical requirements for visual training in amblyopia: A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9123985 (2020).

Brady, A. P. Error and discrepancy in radiology: inevitable or avoidable? Insights into Imaging. 8, 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-016-0534-1 (2017).

Du, J. et al. Differentiating benign from malignant solid breast lesions: combined utility of conventional ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound in comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 81, 3890–3899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.09.004 (2012).

Krupinski, E. A. The role of perception in imaging: past and future. Semin. Nucl. Med. 41, 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2011.05.002 (2011).

Eimer, M. The neural basis of attentional control in visual search. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.05.005 (2014).

Ramezanpour, H. & Fallah, M. The role of Temporal cortex in the control of attention. Curr. Res. Neurobiol. 3, 100038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crneur.2022.100038 (2022).

Wagner, J., Zurlo, A. & Rusconi, E. Individual differences in visual search: A systematic review of the link between visual search performance and traits or abilities. Cortex; J. Devoted Study Nerv. Syst. Behav. 178, 51–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2024.05.020 (2024).

Waite, S. et al. Interpretive error in radiology. Am. J. Roentgenol. 208, 739–749. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.16.16963 (2016).

Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertain. 5, 297–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00122574 (1992).

Levi, D. M. Crowding—An essential bottleneck for object recognition: A mini-review. Vision. Res. 48, 635–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2007.12.009 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their deep gratitude to the participants for their time, the staff who provided the facilities and support for this study, and those who assisted in managing and coordinating the experiment.

Funding

This work was supported by the Double First-Class Construction Project of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (grant number [K524196005]), the China Higher Education Association (grant number [24GC0102]), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number [72301110]), and the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (grant number [2024A04J2279]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W, G.L, and S.S.M; methodology, F.W and G.L; software, G.L; validation, F.W, G.L, and S.S.M; formal analysis, G.L, and S.S.M; investigation, F.W and G.L; resources, F.W and S.S.M; data curation, G.L; writing—original draft preparation, G.L; writing—review and editing, F.W, and S.S.M; visualization, G.L; supervision, F.W and S.S.M; project administration, F.W; funding acquisition, F.W, and S.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Committee of South China University of Technology.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, F., Liu, G. & Man, S.S. Improving lesion detection skills in medical imaging education through enhanced peripheral visual perception. Sci Rep 15, 24130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09253-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09253-y