Abstract

The adsorption of Lead (Pb²) ions onto raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff was examined to ascertain its potential for environmental remediation. The study focused on the thermodynamics, isotherms, and kinetics of Pb² removal across various concentrations, reaction time, pH, dosage, and temperature conditions. The adsorption of Pb²⁺ onto M. esculenta chaff increased from 23.45 mg/g at 10 min to a peak of 74.03 mg/g at 150 min for the raw sample and from 26.24 mg/g at 10 min to a peak of 96.28 mg/g at 180 min for the acid-modified sample at 300 mg/L concentration. The pseudo-first-order model fits the data for raw chaff better, while those from acid-modified chaff showed an excellent fit towards the pseudo-second-order model. The data of equilibrium by the raw M. esculenta chaff indicate an excellent fit for the Langmuir isotherm model, while the Freundlich isotherm well described the acid-modified chaff data. The enthalpy change for the raw and acid-modified chaff are 23.74 kJ/mol and 44.82 kJ/mol respectively which indicates an endothermic adsorption process. The analysis of FT-IR demonstrated that lead ions interacted primarily with hydroxyl, carbonyl, and possibly aromatic groups on the cassava chaff surface. Thus, M. esculenta chaff can be engaged for the removal of lead ions from polluted water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water contamination by heavy metals, particularly lead (Pb²⁺), has escalated into a serious global issue due to its harmful effects on both environmental and human health. Its persistence in the environment means it does not break down naturally, leading to prolonged exposure risks. Human exposure to lead can result in severe health issues, including developmental delays in children, neurological damage, and various systemic effects1– 2. Environmentally, lead contamination affects soil and water quality, disrupts ecosystems, and can enter the food chain, impacting wildlife and human populations alike2. Lead, a persistent organic pollutant, is widely recognized for its toxicity and ability to bioaccumulate in organisms, leading to various health risks, including neurological damage, kidney dysfunction, and developmental disorders, especially in children2,3,4. Lead exposure adversely affects the nervous system, leading to memory and concentration difficulties, as well as behavioral and cognitive development issues in children. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that lead exposure can cause damage to the brain and nervous system, leading to behavior and learning problems, including decreased ability to pay attention and under performance in school5. Similarly, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) documented that small quantity of lead exposure can make children hyperactive, irritable, and appear inattentive with higher levels potentially leading to reading and learning problems, hearing loss and delayed growth7. These problems emphasize the urgent need to prevent lead exposure to safeguard children’s neurological health and development.

The lead presence in natural water sources is primarily attributed to industrial actions, like battery production, mining, metal finishing, and the disposal of waste products and these activities release significant quantities of lead ions into surface water, which then infiltrates ground and drinking water sources1,3. Therefore, the pressing need for efficient, economical, and environmentally friendly methods to remove lead ions from water systems has driven the exploration of innovative adsorbent materials.

Traditional lead removal techniques, like ion exchange, chemical precipitation, and membrane filtration often entail high operational costs, complex infrastructure, and the generation of secondary pollutants2,8– 9. Adsorption, on the other hand, is considered a promising alternative due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, abundant availability, renewability, and environmental friendliness and ability to treat water with low concentrations of pollutants10– 11. However, the high cost of commercial adsorbents, such as activated carbon, has spurred research into low-cost and sustainable alternatives in the form of natural materials and agricultural waste derived adsorbents.

Some of the adsorbents that have been engaged in the uptake of lead ions from aqueous solution are Banana stem4, corncob9, maize husk3, Thaumatococcus danielli leaves11, banana peels12, cocoa pod husks13, coal fly ash14, Sphagmum moss peat15, Shanghai silty clay16), and modified corncob nanocomposite17. These adsorbents contained some functional groups which were responsible for the uptake of lead ions onto the adsorbent surface. Adsorption has emerged as a widely adopted technique in environmental remediation due to its numerous advantages, including cost-effectiveness, operational simplicity, and exceptional efficiency in removing contaminants, even at trace concentrations. Moreover, its ability to selectively target specific pollutants enhances its overall efficacy. The method’s flexibility allows for the utilization of a broad spectrum of naturally occurring solid materials, making it adaptable across various environmental applications18– 19. Recent progress in this field has led to the development of sustainable and innovative adsorbents such as biosorbents, activated carbons, nanocomposites, and polyaniline-based materials, which have demonstrated considerable potential in tackling complex environmental pollutants19– 20. In parallel, increasing attention is being given to alternative adsorbents derived from agricultural wastes, owing to their low cost, abundance, and eco-friendly nature. These agro-waste-based materials align well with green chemistry principles and support circular economy goals by converting waste into value-added products21,22,– 23. Integrating these advanced and alternative adsorbents into adsorption systems can significantly enhance the sustainability and effectiveness of water purification processes, offering practical solutions to a wide range of pollution challenges.

Among various agricultural wastes, Manihot esculentum (cassava) chaff has gained attention as biosorbent for the removal of heavy metal. Cassava, is widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions like Nigeria. It is a staple food crop and generates large quantities of by-products, particularly chaff, during processing23. Research indicates that the functional groups present in cassava peel, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, can facilitate the adsorption of lead ions through mechanisms including ion exchange, complexation, and electrostatic interactions24. Furthermore, modifying the cassava peel, such as through chemical activation or pretreatment, can enhance its adsorption capacity by increasing surface area and introducing additional active sites23,25.

This study presents a novel approach to environmental remediation by utilizing cassava chaff, an often-overlooked agro-waste, as a low-cost biosorbent for the removal of lead (Pb²⁺) ions from aqueous solutions. While previous research has explored the use of cassava peels, this work uniquely focuses on the chaff which is a fibrous by-product generated during cassava processing, especially prevalent in regions like Nigeria. The research stands out by introducing nitric acid modification of the raw chaff, significantly enhancing its physicochemical properties and adsorption efficiency. A key strength of the study lies in its alignment with the principles of green chemistry and circular economy by converting a locally abundant agricultural waste into a high-performance adsorbent. The low cost, local availability, and minimal environmental impact, underscores the potential of acid-modified cassava chaff as a scalable solution for lead removal from contaminated water systems. This study explores the potential of Manihot esculentum chaff as an efficient, low-cost, and sustainable adsorbent for the removal of Pb²⁺ ions from aqueous solutions. Key parameters of pH, contact time, adsorbent dosage, and initial metal ion concentration were investigated to evaluate the adsorption performance and understand the underlying mechanisms. This study explores the potential of cassava chaff for lead ion removal, while providing insights into the thermodynamic, kinetic, and equilibrium aspects of the process. By integrating these approaches, the research aims to develop a fundamental understanding of lead ion interaction with cassava chaff.

Experimentation

Preparation of Manihot esculentum chaff

The Manihot esculentum chaff (MEC) samples were collected from Abalabi village, Ewekoro Local Government Area, Ogun State, Nigeria (6°52’11” N, 3°08’03” E). The collected MEC samples were washed with distilled water, reduced to smaller pieces, and dried at 80 °C for 12 h. The dried material was then ground and ground into powder. To produce a modified form of the sample, 60 g of the powdered MEC sample was placed in a vessel containing 0.1 M HNO3, and tightly sealed. The choice of nitric acid (HNO₃) for the chemical modification of the raw material is based on its well-documented effectiveness in enhancing the physicochemical properties of lignocellulosic biomass. Acid treatment with HNO₃ introduces oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and carbonyl groups onto the surface of the material, which significantly increases its surface polarity and improves affinity for a wide range of pollutants. This oxidative activation also helps to open up blocked pores, increase surface area, and remove impurities or naturally occurring waxes and oils that may inhibit adsorption. Furthermore, HNO₃ modification improves the dispersion of active sites and enhances the cation exchange capacity of the material, making it more reactive toward metal ions and other contaminants. These surface modifications collectively enhance the adsorption efficiency, especially when dealing with heavy metals and organic pollutants. After 12 h of soaking, the samples were removed, washed with distilled water and dried at 100 °C for 6 h to eliminate moisture. The modified Manihot esculentum chaff was labeled as MMEC, while the initial sample was referred to as raw Manihot esculentum chaff (RMEC). For the determination of the point of zero charge (pHpzc), series of 0.01 M NaCl solutions were prepared with the initial pH values adjusted using HCl or NaOH. A 35 mg amount of the cassava chaff was then added to each solution, and the mixtures were agitated and allowed to equilibrate for 3 h. After equilibrium, the final pH of each solution was measured. A plot of the difference between the initial and final pH values (ΔpH) versus the initial pH was then generated, and the point at which ΔpH equals zero indicates the pHpzc.

Characterization of Manihot esculentum chaff

The chemical composition of Manihot esculentum chaff was extensively characterized.The zeta potential of MEC as a function of solution pH was investigated with a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern, UK).The morphology of MEC was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Sigma 300). Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was conducted to identify the major functional groups on the MEC surface. FT-IR spectra in the range of 400–4000 cm⁻¹ were obtained using a Bruker Vector 22 spectrometer with samples prepared in KBr pellets. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer (Netherlands) to examine the crystallographic structure of the adsorbent. The diffraction patterns were recorded over a 2θ range of 10° to 60°. In addition, elemental composition was determined using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy with a Philips PW2400 instrument.

Adsorption evaluations

Pb²⁺ sorption experiments were conducted using a batch equilibration approach in triplicate at room temperature. Stock solutions of Pb²⁺ (1000 mg/L) were prepared by dissolving Pb(NO₃)₂ in distilled water. About 35 mg of the biomass sample was dispersed into 15 mL of the lead solution and the pH was adjusted using 0.1 M solution of either NaOH or HCl. This mixture was then left for equilibration on an orbital shaker and the equilibrium adsorption capacities (qₑ, mg/g) of Pb²⁺ onto MEC and the percentage removal (%) were determined from Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS, Z-2300, Hitachi, Japan).

Where Co, Ce, m and v stand for initial Pb concentration (mg/L), lead concentration at equilibrium (mg/L), mass (mg) of MEC and volume (L) of Pb used.

To evaluate the adsorption performance, a series of batch adsorption experiments were conducted under varying operating conditions, including contact time (10 to 180 min), initial adsorbate concentration (50 to 300 mg/L), solution pH (1.5–7.5), adsorbent dosage (10 to 70 mg), and temperature (25 to 65 °C). Each parameter was varied independently while keeping the others constant to understand its influence on the adsorption process. The optimum conditions were determined based on the maximum removal efficiency or adsorption capacity observed for each parameter. For instance, the optimum contact time was identified as the point beyond which no significant increase in adsorption was observed. Similarly, the optimum pH was the value at which the adsorbent showed the highest affinity for the adsorbate and the same was done for other parameters. These optimum conditions were used for subsequent adsorption isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies to ensure consistent and reliable performance analysis.

Results and discussions

Pollutant concentration and contact time effect on Pb adsorption by Manihot esculenta chaff

The adsorption of lead (Pb²⁺) onto raw Manihot esculenta chaff is governed by key operational factors as the initial Pb²⁺ concentration and the contact time. These parameters impact the kinetics and adsorption capacity, as evidenced by the data provided. For the RMEC as depicted in Fig. 1, it was noticed that at 50 mg/L, sorption capacity rose from 4.34 mg/g at 10 min to a maximum of 19.25 mg/g at 150 min, then decreased to 16.72 mg/g at 270 min. Similarly, at 300 mg/L, adsorption capacity increased from 23.45 mg/g at 10 min to a peak of 74.03 mg/g at 150 min, followed by a slight reduction to 72.37 mg/g at 270 min. From the data of MMEC as shown in Fig. 2, at a Pb concentration of 50 mg/L, the adsorption capacity increases from 7.83 mg/g at 10 min to a maximum of 22.16 mg/g at 180 min, after which it decreases slightly to 20.04 mg/g at 270 min. Similarly, at a higher Pb concentration of 300 mg/L, the adsorption capacity rises significantly from 26.24 mg/g at 10 min to a peak of 96.28 mg/g at 180 min, followed by a decline to 74.46 mg/g at 270 min. The adsorption of Pb²⁺ onto M. esculenta chaff increases initially with contact time, peaks at a certain point, and subsequently declines slightly at extended durations. This trend can be explained by the following adsorption mechanisms:

First, the initial phase (rapid uptake): During the first 150–180 min, adsorption occurs rapidly because of the ample accessibility of active sites on the chaff’s surface, resulting in a strong driving force for Pb²⁺ diffusion onto the adsorbent26,27,28. Second is the equilibrium phase (maximum uptake): As contact time progresses, the adsorption rate slows down as active sites become occupied and the process approaches equilibrium. At 150 and 180 min, the adsorption reaches its peak for RMEC and MMEC. Lastly, is the desorption phase (slight decline): Beyond 150 and 180 min, the decline in sorption capacity may be attributed to desorption or re-dissolution of Pb²⁺ ions from the adsorbent surface into the solution due to weakening electrostatic interactions or competition with other ions present in the aqueous medium26,27,28.

In addition, it was also observed that the adsorption capacity increases with higher initial Pb²⁺ concentrations with the adsorption capacity increasing from 19.25 mg/g to 74.03 at 150 min and from 22.16 mg/g to 96.28 mg/g at a contact time of 180 min when Pb2+ concentration was raised from 50 mg/L and 300 mg/L. This behavior can be as a result of the fact that higher concentration of Pb²⁺ enhances the driving force for mass transfer, enhancing the diffusion of Pb²⁺ ions to the active sites on the M. esculenta chaff surface. But at much higher concentrations, the adsorbent approaches saturation, where all available active sites are occupied, leading to a plateau in adsorption capacity26,27,28. Previous studies have demonstrated that adsorption efficiency increases with Pb²⁺ concentration, but saturation effects become significant at very high concentrations3,11.

Effect of dosage on Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

Adsorbent dosage is a critical factor influencing the removal process, as it ascertains the accessibility of active sites for pollutant binding. The analysis below compares the effects of dosage on the Pb adsorption efficiency of raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff based on the provided data in Fig. 3. For RMEC, the trend observed was that the percentage removal of Pb increases from 54.28% at 10 mg of adsorbent to a maximum of 75.26% at 35 mg. It then slightly declines to 74.38% at 65 mg. Similarly, the percentage removal of Pb increases more significantly, from 58.26% at 10 mg to a peak of 83.48% at 45 mg, after which the removal percentage becomes uniform, indicating equilibrium in the case of the MMEC. The increase in Pb removal with higher dosage is attributed to the greater number of available adsorption sites as the mass of the adsorbent increases8,28. However, the slight decline at 65 mg suggests a saturation effect or overlapping of adsorption sites due to excessive adsorbent, which reduces the effective surface area available for Pb ions8,28. Acid modification enhances the adsorption capacity of Manihot esculenta chaff by introducing or amplifying functional groups (e.g., carboxyl and hydroxyl groups) that interact with Pb ions8,28. This leads to stronger electrostatic attraction and complexation between the Pb ions and the adsorbent surface. The plateau in removal efficiency at higher dosages suggests that the system has reached equilibrium, where adding more adsorbent does not significantly improve performance.

pH effect on Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

Adsorption process is significantly impacted by the pH of a solution, as it influences the charge on the adsorbent surface, the ionization of functional groups, and the speciation of Pb ions in solution. Below is a comparative analysis of the effects of pH on Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff. Based on Fig. 4a, the percentage removal of Pb by RMEC increases from 52.35% at pH 1.5 to a maximum of 78.93% at pH 5.5, after which it decreases to 47.28% at pH 7.5. Whereas for MMEC, the percentage removal of Pb increases from 58.38% at pH 1.5 to a maximum of 87.05% at pH 4.5, after which it decreased to 54.28% at pH 7.5. At low pH (1.5), the adsorbent’s surface is highly protonated due to an abundance of H⁺ ions, leading to contest between Pb²⁺ and H⁺ for the available adsorption sites and this reduces Pb adsorption efficiency10,24,25,26. But as pH increases to 4.5 or 5.5, the protonation of the adsorbent surface decreases, exposing negatively charged functional groups like carboxyl and hydroxyl, which enhance Pb binding through electrostatic attraction and complexation26,29,30,31. Beyond pH 5.5, the removal efficiency declines, possibly due to the precipitation of Pb as Pb(OH)₂, reducing the availability of Pb²⁺ ions for adsorption21,24,25,26. The modified chaff achieves its maximum removal efficiency at pH 4.5 due to the increased availability of active sites and enhanced electrostatic interactions with Pb²⁺ ions as the acid modification introduces stronger binding capabilities compared to the raw chaff21,25–26. The pHpzc is the pH at which the adsorbent’s surface has a neutral charge. At pH levels below the pHpzc, the surface tends to be positively charged, while above it, the surface becomes negatively charged. This characteristic is crucial in understanding adsorption behavior because it influences the electrostatic interactions between the adsorbent and the adsorbate in this case, Pb(II) ions. In this experiments, the values of pHpzc found are 4.0 and 3.8 for the raw and acid-modified cassava chaff samples respectively (Fig. 4b). These values are lower than the observed pH (5.5 for raw and 4.5 for the acid-modified sample) as the highest Pb(II) adsorption capacity. Thus, at this pH, which is above the pHpzc of 3.8 and 4.0, the surface of the cassava chaff would be negatively charged and this negative charge enhances the electrostatic attraction between the cassava chaff adsorbent and the positively charged Pb(II) ions, facilitating more effective adsorption32. In their 2017 study published in Groundwater for Sustainable Development, Siddiqui and Ahmad32 investigated the use of Pistachio shell carbon (PSC) as an adsorbent for removing Pb(II) ions from aqueous solutions and a key aspect of their research involved determining the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of PSC, which they identified at pH 5.0.

Temperature effect on Pb sorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

Temperature is a critical factor in adsorption processes, influencing both the kinetics and thermodynamics of the adsorption mechanism. It impacts the mobility of Pb ions in solution, the interaction strength between the adsorbent and Pb2+, and the stability of adsorption sites. Below is a comparative analysis of the effects of temperature on Pb adsorption for raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff based on the provided data in Fig. 5. The trend observed is that in the case of RMEC, the percentage removal of Pb increases from 51.05% at 298 K to a peak of 78.03% at 318 K, followed by a decrease to 63.44% at 338 K. But for MMEC, he percentage removal of Pb increases from 55.38% at 298 K to a maximum of 84.34% at 313 K, and then decreases to 65.38% at 338 K. The initial increase in adsorption percentage with temperature confirmed the process to be endothermic33. Higher temperatures enhance the mobility of Pb2+ and reduce the viscosity of the solution, facilitating greater interaction between Pb2+ and the adsorbent surface10. The decline in adsorption efficiency at 338 K can be attributed to possible desorption effects, weakening of adsorbent-adsorbate interactions, or structural changes in the raw chaff at elevated temperatures.

Kinetic analysis

Kinetic analysis provides insight into the rate at which lead ions are adsorbed, identifying possible rate-limiting steps in the process, which is crucial for practical applications.

Pseudo-first-order kinetics for Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

The pseudo-first-order kinetic model (PFOKM) is frequently employed to account for adsorption processes, assuming that the adsorption rate is directly proportional to the difference between the equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) and the amount of adsorbate on the adsorbent at any time (qt). The linear form of the equation is given as34,35,36:

To verify which kinetic model is best acceptable, root mean square error (RMSE) and squares error (%SSE) were deployed to examined the data8- 9,11:

Where N is the number of observations and all other variables have been previously defined.

The amount of Pb adsorbed at time t and equilibrium (mg/g) are given as qt and qe, the rate constant of PFOKM is denoted as k1(min− 1). The constants were computed using Fig. 6a and the values listed in Tables 1 and 2. Acid-modified chaff exhibits significantly higher adsorption capacity (ranges from 22.165 mg/g to 90.28 mg/g) than raw chaff (ranged from 19.25 mg/g to 74.03 mg/g), with confirming the enhanced performance due to chemical modification. The close agreement between Qe,exp and Qe,cal for the raw as compared with the acid-modified sample indicates a good fit of the PFOKM for the raw chaff, with minimal deviations. The acid modification also seems to accelerates adsorption kinetics, as evidenced by higher k1 values and this reflects faster Pb binding, which is advantageous in practical applications. The pseudo-first-order model fits the data for both adsorbents well, but slightly better for raw chaff than for acid-modified chaff, due to the higher values of R2. This was confirmed by the lower error values (%SSE and RMSE) than acid-modified chaff, indicating better model predictability. The acid-modified chaff’s higher errors may suggest the need to explore other kinetic models (e.g., pseudo-second-order or intraparticle diffusion) for a better understanding of its adsorption dynamics.

Pseudo-second-order kinetics for Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

The pseudo-second-order kinetic model (PSOKM) assumes that the adsorption process is driven by chemisorption, involving valency forces via exchange or sharing of electrons between the adsorbate and adsorbent. This model is often used to describe adsorption systems with heterogeneous surfaces or complex interactions.

The linear form of the PSOKM is given as34,35,36:

The amount of Pb adsorbed at time t and equilibrium (mg/g) are given as qt and qe, the rate constant of PSOKM is denoted as k2 (g/mg·min). The constants were computed using Fig. 6b and the values listed in Tables 1 and 2. The close match between Qe,exp and Qe,cal indicates that the PSOKM effectively describes the adsorption process for raw chaff. The rate constant (k2) ranges from 0.265 to 1.225 g/mg·min for the raw sample, and range from 0.568 to 1.354 g/mg·min for the acid-modified sample, which higher than those for raw chaff. The increased k2 for the acid-modified adsorbent reflects faster adsorption kinetics, attributed to the acid modification enhancing the chemical reactivity and accessibility of functional groups. The R2 values for the raw adsorbent ranged from 0.974 to 0.988, indicating a strong correlation between the experimental and predicted data, confirming the suitability of the pseudo-second-order model, however, R2 values for the acid-modified are higher, ranging from 0.989 to 0.998, showing an excellent fit to the PSOKM, better than for the raw chaff. Similarly, the acid-modified chaff shows lower error values across all metrics, reinforcing its superior performance and compatibility with the PSOKM.

Intraparticle diffusion kinetics for Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

The intraparticle diffusion model, often represented by Weber and Morris’s equation, evaluates whether diffusion into the pores of an adsorbent is the rate-limiting step. The linear equation is given by37– 38:

Where Kp mg g− 1 min− 0.5 is intraparticle diffusion rate constant, representing the diffusion rate of Pb into the pores, Ci (mg/g) is the intercept, which reflects the boundary layer thickness. The constants were computed using Fig. 6c and the values listed in Tables 1 and 2. The Kp values for RMEC ranges from 3.321 to 16.025 mg g− 1 min− 0.5, showing moderate diffusion rates. The lower Kpvalues at initial stages suggest limited diffusion efficiency, possibly due to less accessible pores or weaker interactions with Pb ions. That of the acid-modified sample ranges from 7.695 to 20.283 mg g− 1 min− 0.5 and this increased reflects enhanced intraparticle diffusion due to improved pore accessibility and stronger chemical interactions introduced by acid modification. The values of the boundary layer thickness (Ci) obtained are in the range of 0.25 to 1.825 mg/g and 0.227 to 0.798 mg/g for RMEC and MMEC respectively, indicating greater variability in boundary layer resistance. The higher Ci values for raw sample suggest that external surface adsorption plays a significant role, with limited diffusion into the internal pores at early stages37– 38. On the other hand, the smaller Ci values indicate reduced boundary layer resistance, highlighting the effectiveness of acid modification in facilitating intraparticle diffusion by enhancing surface properties and reducing steric hindrance. Both raw and acid-modified chaff exhibit strong fits to the intraparticle diffusion model, with R2 values slightly higher for the raw chaff. This suggests that intraparticle diffusion is more dominant in the raw chaff, while acid-modified chaff likely involves additional adsorption mechanisms. The results highlight that while intraparticle diffusion significantly influences Pb adsorption for both raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff, acid modification enhances pore accessibility and reduces external diffusion limitations. For the modified chaff, the adsorption process appears to be a combination of surface adsorption, intraparticle diffusion, and possibly chemisorption.

Elovich kinetics for Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

The Elovich kinetic model is particularly suitable for systems involving heterogeneous adsorbent surfaces and chemisorption processes. It is expressed as38:

Where α (mg/g·min) is the initial adsorption rate, and β (g/mg) describes the extent of surface coverage or activation energy. The constants were computed using Fig. 6d and the values listed in Tables 1 and 2. The values of α ranges from 0.531 to 2.263 mg/g·min for the raw chaff and from 0.068 to 1.967 mg/g·min for the acid modified chaff. The reduced initial adsorption rates indicate a more controlled adsorption process, likely governed by stronger chemisorptive interactions introduced by acid treatment. The surface energy constant (β) ranges from 0.846 to 4.829 g/mg for raw chaff and from 1.353 to 2.449 g/mg in the case of the acid-treated sample, with the acid-treated chaff showing smaller variability and higher values compared to the raw chaff.The higher variability for raw adsorbent reflects heterogeneous adsorption sites and increased energy activation requirements as Pb adsorption progresses, likely due to limitations in pore accessibility or surface interactions, whereas the lower variability for the acid-treated sample suggests more uniform adsorption sites, possibly due to enhanced surface functionality and pore accessibility resulting from acid modification. Both raw and acid-modified chaff fit well to the Elovich model, with slightly higher R2 values for acid-modified chaff. This suggests that acid modification reduces deviations from the model, making the adsorption process more predictable and consistent.

Isotherm studies

Isotherm studies are integral to understanding the distribution of adsorbates between the liquid and solid phases at equilibrium, which gives useful information on the adsorption capacity and efficiency of the biosorbent.

Langmuir isotherm for Pb uptake by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

The Langmuir isotherm model is used to describe adsorption onto a homogeneous surface with finite adsorption sites. It is expressed as36,38,39:

Where qe(mg/g) is the amount of Pb adsorbed, Qm(mg/g): maximum adsorption capacity, representing the monolayer coverage, b(L/mg): Langmuir constant, and RL is separation factor which indicates the favorability of adsorption and is defined as36:

The coefficient of determination (R2), indicates how well the model fits the experimental data. The information presented in Table 3 were deduced using Fig. 7a. The maximum adsorption capacity for RMEC and MMMEC are 78.033 mg/g and 102.351 mg/g, with the MMEC significantly higher than for raw chaff. This value indicates the limited availability of active sites on the raw chaff surface, likely due to unmodified surface chemistry and pore structure, whereas for MMEC, the increased capacity is attributed to acid modification, which enhances pore structure, increases surface area, and introduces functional groups, improving Pb adsorption efficiency. The values of the separation factor (RL) are 0.638 and 0.863, indicating favorable adsorption. However, the moderate RL value suggests limited affinity between Pb and the raw chaff surface.whereas the higher value from MMEC highlights the stronger interaction between Pb ions and the acid-modified chaff, likely due to the increased chemical functionality introduced during acid treatment. Based on the coefficient of determination (R2), the raw M. esculenta chaff adsorbent (R2 = 0.989), indicate an excellent fit of the Langmuir isotherm model to the experimental data, when compared with acid-modified M. esculenta chaff adsorbent (R2 = 0.967), which is slightly lower than for the raw chaff but still indicative of a good fit. This suggests that Pb adsorption onto raw chaff predominantly occurs as monolayer coverage on a homogeneous surface. The reduced R2 may imply that additional mechanisms, such as multilayer adsorption or heterogeneity introduced by acid modification, play a minor role. The acid-modified chaff demonstrated greater affinity for Pb ions, likely due to increased interaction forces such as ion exchange and complexation.

Freundlich isotherm for Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified manihot esculenta chaff

The Freundlich isotherm explains adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces and multilayer adsorption processes. The model is represented as36,39:

Where qe(mg/g) is the adsorbed amount per unit mass of adsorbent, KF(mg/g)(L/mg)1/n: Freundlich constant, indicating adsorption capacity, and 1/n: Heterogeneity factor, related to adsorption intensity. The information presented in Table 3 were deduced using Fig. 7b.

The Freundlich constant values for RMEC and MMEC are 45.508 and 64.285 (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n respectively with the MMEC significantly higher than the raw chaff, demonstrating enhanced adsorption capacity. This indicates that the raw chaff is effective at Pb adsorption but limited compared to modified adsorbents due to its untreated surface and the increase in KF highlights the role of acid modification in enhancing surface area, introducing functional groups, and improving binding interactions with Pb ions. The values of 1/n for RMEC and MMEC are 0.527 and 0.135 respectively, and these values indicate that adsorption onto raw chaff is favorable but less efficient than modified chaff, with stronger adsorption forces and greater affinity between Pb ions and the acid-modified chaff. While both samples fit the Freundlich isotherm well, the acid-modified chaff’s higher R2 suggests a more consistent with this adsorption isotherm, likely due to enhanced surface properties and uniform adsorption sites.

Dubinin-radushkevich (D-R) isotherm for Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

The Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm is commonly used to describe adsorption on microporous materials and to assess the nature of adsorption, distinguishing between physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption)40. This model provides insights into the energy distribution of adsorption sites and the intensity of adsorption.

The general linear form of the D-R isotherm is40– 41:

Where qe is amount of Pb adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g), qm is maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g), β is related to the energy of adsorption (mol2/J2), ε is the Polanyi potential, R gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), Ce is the equilibrium concentration of Pb (mg/L) and T is the temperature (K). The information presented in Table 3 were deduced using Fig. 7c. The maximum adsorption capacity for the raw chaff is 65.025 mg/g, indicating a moderate potential for Pb adsorption, whereas that of the acid modification increases with maximum adsorption capacity of the chaff to 72.381 mg/g. This increase suggests that the modification (likely involving the introduction of functional groups or increased surface area) enhances the material’s ability to adsorb Pb ions, thereby improving its performance as an adsorbent. The adsorption energy constant (E) for raw and acid-modified M. esculenta chaffs are 0.265 and 0.562 kJ/mol. The adsorption energy for the raw sample is relatively low when compared with the the acid-modified chaff. However, since both values are less than 8 kJ/mol, it suggest that the adsorption process predominantly involves physisorption (weak Van der Waals forces)40– 41. This indicates that Pb ions are adsorbed onto the surface through relatively weak interactions. The goodness of the fit is based on the values obtained from the R2 which shows that both materials showed a very good fit to the D-R isotherm, but the acid-modified chaff has a slightly better R2 value, indicating that the adsorption process is more uniform and the isotherm model is more applicable after modification.

Redlich-peterson isotherm for Pb adsorption by raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff

The Redlich-Peterson isotherm (RPI) is a hybrid model that combines elements of the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms. It is especially useful for describing adsorption systems with heterogeneous surfaces or where both types of adsorption mechanisms (chemical and physical) might be at play41. The general linear form of the RPI is41:

Where qe is amount of Pb adsorbed (mg/g), KF is the RPI constant related to adsorption capacity (L/mg), α is the constant related to adsorption intensity, and β is the exponent that governs the nonlinearity of the isotherm. The information presented in Table 3 were deduced using Fig. 7d. In this comparative analysis, the data for raw and acid-modified M. esculenta chaff of the adsorption capacity constant (KF) are 37.924 and 45.243 L/mg. After acid modification, the KF value increases, suggesting an enhanced adsorption capacity due to surface characteristics of the chaff that have been altered to accommodate more Pb ions, making the modified chaff more efficient in removing Pb from aqueous solutions. The exponent β which describes the nonlinearity of the process shows a relatively low β value for the raw chaff (0.263) and the acid-treated sample (0.163) suggests that the adsorption process involves moderate nonlinearity. A further decrease in β for the acid-modified chaff indicates that the modification reduced the nonlinearity of the adsorption process. This suggests that the modification made the adsorption more uniform or consistent across a wider range of Pb concentrations, possibly due to more accessible or homogeneously distributed adsorption sites.

A high R2 (0.985) value suggests that the RPI isotherm fits the experimental data very well for the raw chaff when compared with the acid-treated sample R2 (0.967). This indicates that the adsorption of Pb by raw chaff follows a well-defined adsorption process that can be accurately described by this model. The slightly lower R2 for the acid-modified chaff suggests that while the RPI still fits the data well, the surface modification has introduced additional complexities in the adsorption process, such as changes in surface heterogeneity or adsorption site accessibility. The comparison of the adsorption capacity of M. esculenta chaff adsorbent with other adsorbents as reported in literature are as shown in Table 4 and the values revealed that M. esculenta chaff adsorbent demonstrated high adsorption ability towards Pb ions.

Thermodynamic parameters

Thermodynamic parameters, such as Gibbs free energy (ΔG°), enthalpy (ΔH°), and entropy (ΔS°), are essential for assessing the spontaneity, feasibility, and heat changes associated with the adsorption process. Through a careful evaluation of these parameters, this study aims to explore the interactions between lead ions and the surface of manihot esculentum chaff, thereby providing valuable insights into the potential bonding mechanisms involved. The standard thermodynamic equations used to calculate these parameters are36,47:

Where: R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin (K) and Kd is the equilibrium constant of the adsorption process. Given the provided values for the thermodynamic parameters for both raw and acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff, the comparative analysis was done using Fig. 8 and their values indicated in Table 5. The free energy change ranges from − 0.56 kJ/mol to -2.58 kJ/mol for the raw sample and in the case of the acid-modified chaff, it ranges from − 0.36 kJ/mol to -1.69 kJ/mol. A negative ΔG value indicates that the adsorption of Pb on raw and acid-modified chaff is spontaneous36,47. The absolute values of ΔG for the acid-modified chaff are lower (less negative), indicating that while the process is spontaneous, it is less thermodynamically favorable compared to the raw chaff and this could be due to stronger interactions (chemisorption) in the acid-modified material. The enthalpy changes for the raw and acid-modified chaff are 23.74 kJ/mol and 44.82 kJ/mol respectively. Though, both raw and acid-modified chaff exhibit endothermic adsorption of Pb ions36,47, but the acid-modified chaff has a higher ΔH, suggesting that it may require higher energy for the adsorption process, possibly due to stronger interactions between the adsorbent and the Pb ions. The entropy change for the raw and acid-modified chaff are 10.88 J/mol·K and 6.24 J/mol·K respectively indicating randomness in the system36,47. Although still positive, the entropy change for the acid-modified chaff is lower than that for the raw chaff. This suggests that the acid modification reduces the disorder or randomness in the system, likely because the interactions between the Pb ions and the modified surface are stronger and more ordered, possibly indicating chemisorption.

Desorption study

The comparative desorption study of Lead (Pb²⁺) ions adsorption onto Manihot esculenta (cassava) chaff, both in its raw and acid-modified forms, presents a detailed observation of the material’s efficiency over six cycles of operation (Fig. 9). Desorption is an important aspect in adsorption studies as it provides insights into the material’s ability to release adsorbed ions and its reusability over multiple cycles, which is key to assessing the material’s potential for long-term environmental applications. Overall, the modified sample (MMEC) demonstrates consistently higher desorption efficiency than the raw material (RMEC), indicating that the modification enhances the material’s ability to release the adsorbed substances. Among the desorbing agents tested, hydrochloric acid (HCl) exhibited the highest desorption efficiency for both RMEC and MMEC. MMEC reached approximately 85.3% efficiency, compared to RMEC’s 80.1% (Fig. 9a). This suggests that strong acidic conditions are particularly effective for desorption, likely due to their ability to disrupt strong interactions between the adsorbate and the adsorbent surface. Acetic acid, a weaker acid, also performed well, with MMEC achieving around 78% efficiency and RMEC 73.1%, indicating that even mild acids can significantly promote desorption, especially when the material is modified. Ethanol showed moderate desorption capabilities, with MMEC reaching 68.5% and RMEC 60.1%. These results imply that ethanol is less effective than acidic agents, potentially due to its weaker interaction with the adsorbed species. Water, on the other hand, was the least effective desorbing agent for both samples. MMEC showed a slight improvement over RMEC, but overall, water alone appears insufficient to effectively desorb the material.

The raw chaff shows a progressive decrease in Lead ion adsorption capacity over the six cycles (Fig. 9b). The adsorption percentage starts at 69.28% in the first cycle and gradually declines to 43.28% by the sixth cycle. This suggests a significant reduction in the adsorption efficiency with each successive cycle, indicating that the raw material may suffer from reduced availability of active adsorption sites or undergo changes in surface properties due to desorption or other physical and chemical transformations.

The acid-modified chaff shows a more stable adsorption capacity over the cycles, with less of a decline in performance compared to the raw chaff. The adsorption percentage starts at 72.39% in the first cycle and only drops to 54.04% by the sixth cycle. The more gradual decline in performance suggests that acid modification, likely involving the introduction of functional groups like carboxyl or hydroxyl groups, may have improved the material’s structural stability and the availability of active sites for adsorption. The surface modification could lead to enhanced Pb²⁺ ion binding affinity, resulting in a more stable adsorption over multiple cycles. Both materials show a decline in efficiency with increasing cycles, which is typical in adsorption studies. However, the slower degradation of the acid-modified chaff suggests that it may be more suitable for environments where multiple adsorption/desorption cycles are necessary, such as in industrial or environmental applications where Lead ion removal needs to be sustainable over time.

Characterizations of the adsorbent

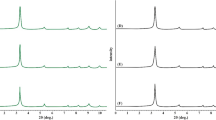

Analysis of the FT-IR of Manihot esculenta chaff

The analysis of the FT-IR spectra of raw, acid-treated cassava chaff before and after the adsorption of lead (Fig. 10) with the identified peaks and their possible assignments. This analysis demonstrated that lead ions interacted primarily with hydroxyl, carbonyl, and possibly aromatic groups on the cassava chaff surface, altering the chemical environment reflected in the FT-IR spectra. In the RMEC spectrum, broad peaks around 3450 cm⁻¹ are attributed to O–H or N–H stretching vibrations, indicating the presence of hydroxyl or amine groups48– 49. This region is also prominent in MMEC, but shows changes in intensity and sharpness, suggesting that chemical modification enhanced or altered these groups. The band around 2964 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C–H stretching vibrations and is consistently observed across all spectra, with slight shifts (2971 cm⁻¹) indicating structural changes due to modification.

A distinct peak at 1750 and 1685 cm⁻¹ and 1745, and 1687 cm⁻¹ observed in the RMEC and MMEC spectra, typically associated with C = O stretching in carbonyl-containing functional groups such as carboxylic acids or esters48– 49. In the MMEC + Pb spectrum, this peak shifts with decreases in intensity, implying coordination between these groups and Pb²⁺ ions. This interaction suggests that the carbonyl groups play a role in metal ion binding during adsorption. The region from 1500 to 500 cm⁻¹ is particularly rich in peaks for all three samples. In MMEC and MMEC + Pb, this region shows more pronounced and sharper peaks compared to RMEC. These changes can be attributed to functional groups such as C–O, C–N, and possibly metal-oxygen interactions. After Pb adsorption, notable shifts and the emergence of new peaks within this region further support the fact that Pb²⁺ ions interact directly with the modified chaff surface, forming metal-ligand complexes.

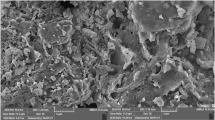

Analysis of the SEM of Manihot esculenta chaff

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis of Manihot esculenta (cassava) chaff before and after lead adsorption reveals a porous surface morphology in both states, with minimal observable differences post-adsorption (Fig. 11). The presence of pores in the chaff facilitates lead ion uptake, serving as active sites for adsorption. The lack of significant morphological changes after adsorption suggests that the adsorption process may primarily involve surface interactions, such as ion exchange or complexation, rather than substantial structural alterations or pore blockage indicating that the adsorption mechanism does not drastically alter the adsorbent’s morphology. Additionally, the consistent porous structure observed in SEM images before and after adsorption implies that the chaff maintains its structural integrity throughout the process, which is advantageous for potential reuse in multiple adsorption cycles. This resilience is crucial for the practical application of biomass-based adsorbents in wastewater treatment, as it ensures sustained performance over time.

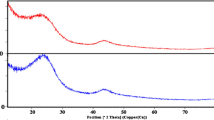

Analysis of the XRD of Manihot esculenta chaff

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis provides insight into the structural changes that occur in manihot esculentum chaff during chemical modification and subsequent lead (Pb²⁺) adsorption as shown in Fig. 12. The diffraction pattern of raw sample prior to chemical modification (RMEC), exhibits broad and relatively intense peaks around 2θ = 16–24°, which are characteristic of the semi-crystalline nature of lignocellulosic biomass50– 51. These peaks are primarily associated with the presence of cellulose I, indicating a structure that retains both amorphous and crystalline regions, typical of untreated plant materials50– 51. Upon chemical modification, as shown in the red pattern for MMEC, the peak intensity noticeably decreases and the peaks become broader. This change suggests a partial breakdown of the ordered crystalline cellulose domains and an increase in the amorphous content of the material. The chemical treatment likely disrupts the hydrogen bonding within cellulose fibers and introduces functional groups that enhance the material’s surface properties, such as porosity and active site availability, making it more suitable for adsorption applications.

After Pb²⁺ adsorption (MMEC + Pb), the XRD pattern exhibits even more significant broadening and a further reduction in intensity. These changes imply strong interactions between Pb²⁺ ions and the functional groups on the biosorbent surface. The absence of sharp new peaks indicates that Pb²⁺ is not forming a distinct crystalline phase but is instead adsorbed in an amorphous or dispersed manner. The XRD results confirm the successful structural modification of RMEC and the effective adsorption of Pb²⁺, aligning well with FTIR data and validating the potential of MMEC as a capable biosorbent for heavy metal remediation.

Elemental analysis

The chemical composition of MMEC before and after adsorption of lead ions is shown in Fig. 13. before adsorption, the presence of Na, Mg, Si, K and Fe were observed. The presence of Pb ions and the disappearance of K and Fe after the adsorption process suggests the uptake of Pb via ion-exchange process52.

Conclusions

This study examined the role of acid modification on the adsorption performance of M. esculenta chaff adsorbent for the uptake of Pb²⁺ ion. The optimum conditions at which maximum adsorption was achieved are initial Pb2+ concentration of 300 mg/L, pH of 4.5 and 5.5 for MEC and MMEC, dosage of 35 mg and 45 mg for MEC and MMEC, and temperature of 318 K and 313 K for MEC and MMEC respectively. Raw M. esculenta chaff adhered to the Langmuir isotherm model, while acid-modified Manihot esculenta chaff obeys the Freundlich isotherm. Kinetic studies demonstrated that Pb²⁺ ion adsorption followed pseudo-first- and pseudo-second-order kinetics by raw and acid-modified M. esculenta chaff respectively. Thermodynamic analysis confirmed that the adsorption of Pb²⁺ ions was spontaneous and endothermic, favoring higher adsorption at elevated temperatures. Acid-modified chaff exhibited better stability and higher reusability across multiple adsorption-desorption cycles, making it a more viable option for long-term applications. The study underscores the potential of Manihot esculenta chaff, particularly when acid-modified, as a sustainable and cost-effective biosorbent for the removal of Pb²⁺ ions from contaminated water sources.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sall, M. L., Diaw, A. K. D., Gningue-Sall, D., Aaron, E., Aaron, J. J. & S., & Toxic heavy metals: impact on the environment and human health, and treatment with conducting organic polymers, a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09(( (2020).

Chowdhury, R., Chowdhury, S., Mazumder, M. A. J. & AlAhmed, A. Removal of lead ions (Pb2+) from water and wastewater: a review on the Lowcost adsorbents. Appl. Water Sci. 12, 185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-022-01703-6(2022) (2022).

Adeogun, A. I., Idowu, M. A., Ofudje, E. A., Kareem, S. O. & Ahmed, S. A. Comparative biosorption of Mn(II) and Pb(II) ions on Raw and oxalic acid modified maize husk: kinetic, thermodynamic and isothermal studies. Appl. Water Sci. 3, 167–179 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Banana stem and leaf Biochar as an effective adsorbent for cadmium and lead in aqueous solution. Scientifc Rep. 12, 1584 (2022).

Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC). Lead exposure symptoms and complications. Available online at:https://www.cdc.gov/lead- prevention/symptoms-complications/index.html. (2024).

Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC). lead exposure in children: prevention, detection, and management. Retrieved from, (2019). https://www.cdcgov/nceh/lead/prevention/default.htm

American academy of child and adolescent psychiatry. lead exposure in children affects brain and behavior. Available online at: (2023). https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF - Guide/Lead-Exposure-In-Children-Affects-Brain-And-Behavior-045.aspx

Ofudje, E. A. et al. Nano-Rod hydroxyapatite for the uptake of nickel ions: effect of sintering behaviour on adsorption parameters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Jece.2021.105931( (2021).

Adeogun, A. I., Ofudje, E. A., Idowu, M. A. & Ahmed, S. A. Kinetic, thermodynamic and isotherm parameters of biosorption of Cr(VI) and Pb (II) ions from aqueous solution by biosorbent prepared from corncob biomass. Indian J. Inorg. Chem. 7, 119–129 (2012).

Bhattacharya, A. K., Mandal, S. N. & Das, S. K. Adsorption of Zn(II) from aqueous solution by using different adsorbents. Chemical Eng. Journal, 123 (1–2), 43–51 .https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2006.06.012(2006).

Ademoyegun, A. J., Babarinde, N. A. A. & Ofudje, E. A. Sorption of Pb(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II) ions from aqueous solution using Thaumatococcus Danielli leaves: kinetic, isotherm, and thermodynamic studies. Desalination Water Treat. 273, 162–171. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2022.28877 (2022).

Afolabi, F. O., Musonge, P. & Bakare, B. F. Bio-sorption of copper and lead ions in single and binary systems onto banana peels. Cogent Eng. 8 (1), 1886730. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2021.1886730 (2021).

Obike, A. I., Igwe, J. C., Emeruwa, C. N. & Uwakwe, K. J. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of Cu (II), cd (II), Pb (II) and Fe (II) adsorption from aqueous solution using cocoa (Theobroma cacao) pod husk. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage., 22 (2), 2. https://doi.org/10.4314/jasem.v22i2.5(2018).

Astuti, W., Chafdz, A., Al-Fatesh, A. S. & Fakeeha, A. H. Removal of lead (Pb(II)) and zinc (Zn(II)) from aqueous solution using coal fly Ash (CFA) as a dual-sites adsorbent. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 34: 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2020.08.046(2021).

Ratoi, M., Bulgarire, L. & Macoveanu, M. Removal of lead from aqueous solution of adsorption using Sphagmum moss peat. Chem. Bull. Politehnica Univ. 53 (67), 1–2 (2008).

Wang, J. & Zhang, W. Evaluating the adsorption of Shanghai silty clay to Cd(II), Pb(II), As(V), and Cr(VI): kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193 (3), 131 (2021).

Kholod, H. K., Attia, M. S., Nabila, S. A. & Enas, M. A. T. Kinetics and isotherms of lead ions removal from wastewater using modified corncob nanocomposite. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 130, 108742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2021.108742 (2021).

Badran, A. M., Utra, U., Yussof, N. S. & Bashir, M. J. K. Advancements in adsorption techniques for sustainable water purification: A focus on lead removal. Separations 10, 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10110565 (2023).

Kaci, M. M., Akkari, I., Pazos, M., Atmani, F. & Akkari, H. Recent trends in remediating basic red 46 dye as a persistent pollutant from water bodies using promising adsorbents: a review. Clean. Techn Environ. Policy. 27, 773–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-024-03026-3 (2025).

Anjum, A. et al. A review of novel green adsorbents as a sustainable alternative for the remediation of chromium (VI) from water environments. Heliyon 9, e15575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15575 (2023).

Akkari, I., Kaci, M. M. & Pazos, M. Revolutionizing waste: Harnessing agro-food hydrochar for potent adsorption of organic and inorganic contaminants in water. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-13171-3 (2024).

Tiliouine, Y. et al. A sustainable biosorbent for effective methylene blue adsorption. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 9, 31 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41101-024-00265-9

M. O., Henry, O. O., Ufuoma, M. O. & Samuel E. A. Value added cassava waste management and environmental sustainability in Nigeria: A review. Environ. Chall. 4, 100127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100127 (2021).

Akpomie, K. G. & Dawodu, F. A. Potential of a low-cost adsorbent for the removal of heavy metals from wastewater. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 9 (4), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjbas.2015.02.002 (2015).

Daniel, S. et al. Chemical modifications of cassava Peel as adsorbent material for metals ions from wastewater. J. Chem. 3694174 https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3694174 (2016).

Anwar, J., Shafique, U., Waheed-uz-Zaman, Salman, M., Dar, A. & Anwar, S. Removal of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from water by adsorption on peels of banana. Bioresour. Technol., 101(6), 1752–1755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2009.10.02(2010).

Schwantes, D. et al. Chemical modifications of cassava Peel as adsorbent material for metals ions from wastewater. J. Chem. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3694174 (2016).

Demirbas, A. Heavy metal adsorption onto agro-based waste materials: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 157 (2-3), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.01.024 (2008).

Bai, W. et al. Removal of Cd2+ ions from aqueous solution using cassava starch– based superabsorbent polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134 (17), 44758 (2017).

Wang, S. & Peng, Y. Natural zeolites as effective adsorbents in water and wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 156 (1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2009.10.029 (2010).

Huang, J., Yuan, F., Zeng, G., Li, X., Gu, Y., Shi, L., … Shi, Y. Influence ofpHon heavy metal speciation and removal from wastewater using micellar-enhancedultrafiltration. Chemosphere, 173, 199–206. (2017).

Gao, X., Hassan, I., Peng, Y., Huo, S. & Ling, L. Behaviors and influencing factors of the heavy metals adsorption onto microplastics: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 319, 128777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128777 (2021).

Siddiqui, S. H. & Ahmad, R. Pistachio shell carbon (PSC) – an agricultural adsorbent for the removal of Pb(II) from aqueous solution. Groundw. Sustainable Dev. 4, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2016.12.001 (2017).

Ganesan, M. & Thiyagarajan, C. Adsorption and desorption kinetics of lead from aqueous solutions by biosorbents. Chem. Pap. 78, 993–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-023-03136-0 (2024).

Kushwaha, A., Rani, R. & Patra, J. K. Adsorption kinetics and molecular interactions of lead [Pb(II)] with natural clay and humic acid. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-019-02411-6 (2019).

Mustapha, S. et al. Adsorption isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies for the removal of Pb(II), Cd(II), Zn(II) and Cu(II) ions from aqueous solutions using Albizia lebbeck pods. Appl. Water Sci. 9 (142). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-1021-x (2019).

Ofudje, E. A. et al. Simultaneous removals of cadmium (II) ions and reactive yellow 4 dye from aqueous solution by bone meal derived apatite: kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamic evaluations. J. Anal. Sci. Tech. 11, 7 (2020).

Al-Harby, N. F., Albahly, E. F., Mohamed, N. A. & Kinetics Isotherm and thermodynamic studies for efficient adsorption of congo red dye from aqueous solution onto novel Cyanoguanidine-Modified Chitosan adsorbent. Polymers 13, 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13244( (2021).

Wang, J. & Guo, X. Adsorption isotherm models: classification, physical meaning, application and solving method. Chemosphere 127279 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127279 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Adsorption optimization of uranium(VI) onto polydopamine and sodium titanate co- functionalized MWCNTs using response surface methodology and a modeling approach. Colloids Surf., A. 627, 127145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.12714 (2021).

Shams, K., Sidqi, A., A-K., Muhammad, S. K. & Shirish, P. Surfactant Adsorpt. Isotherms: Rev. ACS Omega 6(48): 32342–32348 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c04661. (2021).

Lubbad, S. H. & Al-Batta, S. N. Ultrafast remediation of lead-contaminated water applying sphagnum peat moss by dispersive solid-phase extraction. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 77, 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2019.1674582 (2020).

Khalfa, L., Sdiri, A., Bagane, M. & Cervera ML A calcined clay fxed-bed adsorption studies for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 278, 123935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123935 (2021).

Aigbe, R. & Kavaz, D. Unravel the potential of zinc oxide nanoparticle- carbonized sawdust matrix for removal of lead(II) ions from aqueous solution. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 29, 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2020.05.007 (2021).

Nawaz, T., Zulfqar, S., Sarwar, M. I. & Iqbal, M. Synthesis of Diglycolic acid functionalized core-shell silica coated Fe3O4 nanomaterials for magnetic extraction of Pb(II) and Cr(VI) ions. Sci. Rep. U K. 10, 10076. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67168-2 (2020).

Elsayed, A. E., Mohamed, L. M. & Ahmed, F. S. FaridaA.A. Novel metal based nanocomposite for rapid and efficient removal of lead from contaminated wastewater sorption kinetics, thermodynamics and mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 12, 8412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12485-x (2022).

Şenol, Z. M. & Arslanoğlu, H. Influential biosorption of lead ions from aqueous solution using sand Leek (Allium scorodoprasum L.) biomass: kinetic and isotherm study. Biomass Conv Bioref. 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-05539- (2024).

Şenol, Z. M., Çetinkaya, S. & Arslanoglu, H. Recycling of Labada (Rumex) Biowaste as a value-added biosorbent for Rhodamine B (Rd-B) wastewater t reatment: biosorption study with experimental design optimisation. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 13 (3), 2413–2425 (2023).

Kayiwa, R., Kasedde, H., Lubwama, M. & Kirabira, J. B. Mesoporous activated carbon yielded from pre-leached cassava peels. Bioresour Bioprocess. 8 (1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-021-00407-0 (2021).

Gin, W. A., Jimoh, A., Abdulkareem, A. S. & Giwa, A. Utilization of cassava Peel waste as a Raw material for activated carbon production: approach to environmental protection in Nigeria. Inter J. Engin Resear Tech. 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.17577/IJERTV3IS10191 (2014).

Gugulothu, B. et al. S.R. Manihot esculenta tuber microcrystalline cellulose and woven bamboo fiber-reinforced unsaturated polyester composites: mechanical, hydrophobic, and wear behavior. Mater. Res. Express. 10, 035302 (2023).

Marcilene, N. & Schoelera, R. L. de Oliveira Bassob and Paulo R. Stival Bittencour, Cellulose nanofibers from cassava agro- industrial waste as reinforcement in pva films. Quim. Nova, 43(6): 711–717. https://doi.org/10.21577/0100-4042.20170542(2020).

Sulaiman, N. S. et al. Characterization and Ofloxacin adsorption studies of chemically modified activated carbon from cassava stem. Materials 15, 5117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15155117 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Northern Border University, Saudi Arabia for supporting this work through the project number “NBU-CRP-2025-2985”. Authors also wish to acknowledge the financial support received from Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R65), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have equal contributions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Rayyes, A., Arogundade, I., Ofudje, E.A. et al. Thermodynamic, isotherm and kinetic studies lead ions adsorption onto Manihot esculenta chaff surface. Sci Rep 15, 27672 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09307-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09307-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Oxidised carbon nanoplatelets for remediation of inorganic pollutants from a natural industrial effluent

Discover Chemistry (2025)