Abstract

The communication network of Unmanned Aerial Drones (UAD) is expected to become a vital element in the development of next-generation wireless networks, offering flexible infrastructure that extends network coverage to remote or disaster-stricken locations while enhancing capacity during critical events and large-scale emergencies. As UAD technology evolves, its role in ensuring consistent, widespread connectivity becomes more essential, though it faces challenges such as high latency, low spectral efficiency, and fairness issues across multiple drones. This research presents an optimization framework designed for multi-UAD communication networks based on Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access (NOMA) to address these difficulties. The framework focuses on optimizing ground user-to-UAD associations and drone power allocation to maximize spectral efficiency. The primary optimization problem is a mixed-integer, nonconvex, and nonlinear task, which seeks to maximize the sum-rate while addressing issues of UAD-user association and power distribution, complicated by interference and binary decision variables. To manage this complexity, we first optimize UAD-user associations under fixed NOMA power allocation and then optimize the power allocation for each NOMA-enabled ground user connected to the drones. Our numerical results show that this framework provides better performance than traditional orthogonal multiple access (OMA)-based optimization methods and other benchmark NOMA-based techniques, offering improved spectral efficiency, lower complexity, and faster convergence, making it an effective solution for enhancing UAD network performance across a range of dynamic scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unmanned aerial drones (UADs) operate without a human pilot onboard. These vehicles commonly referred to as drones are anticipated to play a pivotal role in next-generation wireless networks. According to IoT Analytics projections the number of connected devices will rise to 30 billion by 2030. Drones have become extremely useful instruments in this extensive ecosystem, able to be controlled remotely by a pilot positioned at a ground control or carry out autonomous flight missions according to pre-programmed flight plans1. UADs provide flexibility by either adhering to preset instructions or adjusting to changing mission objectives.

UADs potential has been thoroughly investigated one study2 for example looks at how well they operate in coastal-zone applications and shows how adding UADs to the network may lower execution latency and boost computation speed in mobile edge computing networks. The capabilities of UADs in coastal-zone applications have advanced thanks in large part to this integration3. Equipped with sensors, cameras and specialized tools UADs are widely used for tasks such as surveillance, inspections, data acquisition, monitoring and other related activities4. At first UADs were mostly used for military purposes however UADs progressively expanded into civilian sectors, finding uses in fields like intelligent logistics and precision agriculture as technological advancements decreased their size and cost5.

Various UAD kinds are made to perform particular functions and duties usually having four to six rotors multi-rotor UADs offer precision control and vertical lift which makes them perfect for short-range inspections, aerial photography and filming6. On the other hand fixed-wing UADs have static wings and a design similar to that of traditional aeroplanes. These aircraft which specialise in observation and reconnaissance duties, perform exceptionally well on extended missions. Their efficiency in covering extensive distances is notable; however, a dedicated runway is needed for its takeoff and landing. Single-rotor and hybrid fixed-wing UADs combine the efficiency of fixed-wing aircraft with the vertical takeoff and landing capabilities of helicopters, offering versatility for extended missions.

In next-generation wireless networks, non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) is emerging as a promising multiple access technique. Unlike conventional methods that divide resources by time or frequency, NOMA utilizes power domain multiplexing, allowing multiple users to share the same time slot, frequency band, or coding resources7. This flexibility enables UADs to manage multiple users simultaneously within a single resource block by implementing successive interference cancellation (SIC) at the receivers. NOMA’s ability to support increased connectivity in UAD networks alleviates resource scarcity issues, enabling UADs to efficiently perform various communication tasks.

The integration of NOMA with UADs offers significant benefits, including improved spectral efficiency, reduced latency, and enhanced data transmission rates8,9.. The rapid proliferation of smart devices has widened the gap between available radio resources and the increasing demand for high-data-rate, low-latency communications10. Furthermore, the coming widespread implementation of 6G networks presents obstacles concerning hardware complications, energy usage, and the unbelievable increase in ultra-wideband connection and real-time services11. As mentioned above, UADs offer significant advantages due to their wide coverage area, capability for data collection, device connectivity, ease of deployment, and precise monitoring. On the other hand, RIS represents a distinct technology that brings substantial enhancements to any network or device with which it interacts. These enhancements include augmenting signal capacity and channel gain, offering cost-effectiveness, and enabling deployment on various surfaces. Optimizing phase shifts at the RIS and power allocation at the transmitter is essential for achieving the highest sum-rate and minimizing energy consumption in a multiple-user RIS-assisted multiple-input single-output (MISO) systems12.

The topic of UAD communications has garnered significant attention, and significant work has been conducted to address various problems in this area. Due to the mobility of UAD communications, significant problems and challenges exist. To achieve efficient UAD communications, several key challenges must be addressed including drones’ limited onboard energy resources, which restrict their flying time13,14,15. Drones can be efficiently used in rescue operations, surveillance of strategic areas, providing networks in flood areas, courier delivery, etc. Therefore, energy-efficient drone design is crucial for efficient and sustainable UAD communications16,17. Security and reliability are also major concerns, as UAD communication, which relies on line-of-sight broadcast channels, is more vulnerable to eavesdropping than traditional terrestrial systems18,19. Additionally, efficient trajectory planning and resource optimization are essential for multi-UAD scenarios, where all drones share the same spectrum resources. Poorly managed co-channel interference can drastically reduce system performance20. As a result, poorly managed co-channel interference can drastically reduce system performance.

Further, providing massive connections using limited system resources can be another challenge in next-generation wireless communications. More specifically, traditionally, a UAD can communicate with a ground user by assigning a frequency resource that cannot be assigned to another ground user by the same UAD21. One possible solution for massive connectivity in UAD communications is to utilize NOMA as an air interface technique. By using superposition coding and SIC decoding techniques, NOMA enables UADs to accommodate multiple ground users through a single frequency resource. However, the successful implementation of NOMA depends on precise SIC decoding at the receivers, a process that becomes increasingly difficult due to the high mobility of UADs22. Errors in SIC decoding can significantly degrade system performance, highlighting the need for intelligent NOMA receiver designs for efficient signal decoding23.

Most of the existing literature has focused on UAD communications using traditional orthogonal multiple access (OMA) techniques such as code-division multiple access, frequency-division multiple access, and time-division multiple access. Moreover, many studies have considered single-cell UAD communication scenarios, which do not involve co-channel interference. In this study, we examine a more practical scenario involving multiple UADs, where each UAD shares the same spectrum resource and serves multiple users using the NOMA protocol. In the considered scenario, each UAD introduces interference to other UADs, while users within the same UAD coverage area experience NOMA interference. Such a scenario results in non-convex optimization problems, which are highly complex and challenging to solve. This work presents a novel optimization framework for multi-UAD communications that maximizes spectral efficiency while adhering to constraints on minimum data rates, user association, and power control for NOMA ground users. The Important acronyms summary are show in Table 1

Related work

In recent years, UAD communication has gained significant attention for its role in enhancing wireless coverage, particularly in underserved or high-demand areas such as rural regions, disaster zones, and large public events. UAD networks provide adaptable and flexible infrastructure but face challenges like latency, limited spectral efficiency, and user fairness, especially in dense deployments where multiple UADs serve numerous ground users. Initial studies, such as those by24 and25, focused on optimizing UAD deployment and trajectory to maximize coverage and minimize latency, relying primarily on orthogonal access methods and fixed power allocations. These methods, however, lack the flexibility needed for highly dynamic environments and often result in high latency and inter-UAD interference in dense networks. To address these limitations, spectrum sharing and dynamic power allocation approaches were introduced, as seen in works such as26, where interference is managed by dynamically adjusting UAD power levels based on network load. While effective, these methods alone cannot fully achieve the required spectral efficiency and fairness for emerging high-density UAD networks.

NOMA has emerged as a promising approach to address these limitations by enabling multiple users to share the same spectrum via power-domain multiplexing, thus enhancing spectral efficiency and supporting higher user density in UAD networks. Introduced27power-domain NOMA for UAV-assisted wireless networks, which improves efficiency by allocating higher power to users with weaker channel conditions, a technique particularly suited for UAD networks where user positions and channel conditions vary widely. Building on28, developed a NOMA-based resource allocation model for UADs, focusing on optimizing throughput through power and bandwidth adjustments, and29 proposed a similar model that integrates UAD placement optimization to maximize spectral efficiency. These studies confirmed that NOMA can significantly improve spectral efficiency in UAD-networks. However, however, they typically treat UAD-user association and power allocation as separate tasks, limiting their overall optimization effectiveness.

The need for joint optimization of UAD-user associations and power allocation to maximize system performance has led to further research. Proposed30 a joint optimization framework that combines user associations and power control to maximize the sum-rate in NOMA-based UAV networks. However, their model assumes ideal channel state information (CSI) and fixed UAD positions, assumptions that may not hold in real-world applications where UADs and users are mobile. Moreover, the computational complexity of such joint optimization methods has posed a significant challenge in scaling these solutions for larger networks. Later31 introduced an energy-efficient algorithm for joint resource allocation in multi-UAD NOMA networks, which improves efficiency but still struggles to effectively manage interference in denser UAD deployments.

Recent studies on NOMA have focused on enhancing spectral efficiency in systems with high user density, including UAD networks. While NOMA has been explored for multicell cellular systems with In-band Full Duplex (IBFD) transmission challenges such as interference management and dynamic user association in UAD networks remain largely unaddressed. Existing OMA struggle with scalability and resource inefficiency. Despite these advances, existing frameworks often fail to adequately address the combined challenges of interference management, user fairness, and computational efficiency in large-scale UAD deployments. To summarize the gaps, Table 2. showed the comparison between related work and proposed work.

Motivation and contributions

Unmanned Aerial Device (UAD) communications are gaining significant attention due to their promising potential in providing mobile, high-capacity, and flexible wireless communication solutions. However, several challenges arise from the unique characteristics of UADs, including limited onboard energy, high mobility, security concerns due to line-of-sight wireless channels, and interference management in dense deployments. In particular, managing co-channel interference in multi-UAD networks and ensuring efficient trajectory planning and resource allocation are crucial for optimizing communication performance.

One of the most promising solutions for improving the capacity of UAD communications is Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access (NOMA). NOMA allows multiple users to share the same frequency resources, but its performance is highly impacted by issues such as power control, user association, and efficient Signal Interference Cancellation (SIC) decoding, particularly in high-mobility scenarios. In order to improve spectrum efficiency and guarantee optimal system performance under practical restrictions this work tackles these issues by developing innovative optimisation techniques for multi-UAD communications.

Building on these existing approaches, this paper introduces a novel sequential joint optimization framework that jointly optimizes UAD-user association and power allocation. Our strategy effectively balances the computational complexity while enhancing spectral efficiency and interference management in contrast to conventional approaches that handle these tasks independently. Our approach dramatically outperforms current solutions by concentrating on dynamic UAD deployments providing a scalable and useful solution for multi-UAD networks found in the real world.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

1.

Framework development: An innovative optimization framework for multi-UAD downlink communication using the NOMA protocol is presented in this research. By maximizing user allocation and transmission power regulation the framework addresses issues with co-channel and NOMA interference enhancing spectral efficiency and offering customised Quality of Service (QoS) for every ground user and the overall system performance and user satisfaction are greatly improved by this innovative method.

-

2.

Problem formulation and optimization: Taking into account restrictions such user association, power control, and minimum data rate requirements for NOMA users, we define the problem of sum-rate maximisation for multi-UAD communications. User association is the first step in an organised solution strategy, which is then followed by an optimisation of power allocation. KKT criteria are used to address the optimisation problem balancing service quality and spectral efficiency while taking into account realistic system restrictions.

-

3.

Algorithm development and complexity analysis: The paper proposes a sequential joint optimization approach to reduce computational complexity compared to traditional methods. We evaluate the suggested algorithm’s complexity and show that it scales effectively for dynamic, large-scale UAD networks. Computational burden is reduced without compromising performance thanks to the successive optimisation of user association and power allocation. The suggested approach is validated by thorough Monte Carlo simulations, which demonstrate definite improvements in spectrum efficiency and fast convergence when compared to the benchmark NOMA and OMA schemes.

-

4.

Extension to high mobility and co-channel interference: This work shows an optimization approach designed especially for high-mobility multi-UAD networks in contrast to previous research that concentrates on static or simplified models and the suggested method ensures better SIC decoding performance by addressing dynamic user association, power control and trajectory optimization under interference and mobility restrictions. The usefulness of the suggested approach in actual UAD communication circumstances is shown by extensive simulations.

-

5.

Fair power allocation: One key challenge in NOMA systems is ensuring fair power distribution among users and our proposed optimization framework addresses this by balancing power allocation to guarantee an efficient and fair resource distribution across users thus preventing the performance degradation often caused by uneven power control in traditional NOMA schemes.

-

6.

Computational complexity reduction: The optimization methods computational complexity is a significant issue in large-scale UAD networks and the suggested sequential method is more feasible for implementation in actual UAD communication systems since it drastically lowers computational overhead when compared to approaches based on Lagrange duality or convex approximation.

-

7.

Novel sequential joint optimization: This paper introduces a novel optimization framework for NOMA-based multi-UAD networks, which jointly optimizes UAD-user association and power allocation in a sequential manner to enhance spectral efficiency while managing both inter- and intra-UAD interference. This approach simplifies the computational complexity, making it feasible for practical, large-scale implementations while outperforming benchmark NOMA and OMA schemes in terms of convergence speed and spectral efficiency.

-

8.

Energy efficiency: Energy efficiency is a crucial factor in UAD networks, particularly for battery-operated drones that have limited flight times. To optimize energy usage, we extend our optimization framework to minimize energy consumption while maintaining the required sum-rate. By incorporating a power allocation strategy that takes into account both the transmit power and the UAD’s energy constraints, we achieve a balanced trade-off between performance and energy consumption. Our simulation results show that the proposed method not only enhances the spectral efficiency but also significantly reduces energy usage compared to traditional NOMA and OMA-based systems.

System model and problem formulation for NOMA multi-UAD communications

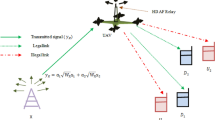

A multi-UAD network is considered as illustrated in Fig. 1, where each UAD communicates with ground UAD users following downlink NOMA transmission. The set of UADs is shown as D while the set of ground users served by each UAD is denoted as U, where ground users are randomly located in the coverage area of UAD. Let us describe the set of UADs and ground users as \(\mathscr {D}=\{d|1,2,\dots ,D\}\) and \(\mathscr {U}=\{u|1,2,\dots ,U\}\). Moreover, the UAD and ground user indices are denoted as UAD d and ground user u, respectively. In the proposed system model, it is assumed that:

-

UADs and their associated ground users use a single antenna for communications.

-

UADs have knowledge of the CSI of their serving ground users.

-

All UADs share the same spectrum at the same time to achieve high spectral efficiency.

-

The placement of UADs has been optimized prior to the proposed optimization process.

Based on the proposed framework, ground users in UAD d experience two types of interference, i.e., intra-UAD interference and inter-UAD interference. More specifically, intra-UAD interference occurs due to NOMA transmission among ground users in the same UAD coverage area after the SIC decoding process. Inter-UAD interference arises interference is due to co-channel reuse among all UADs. To ensure the QoS and mitigate interference issues, the objective of this work is to optimize the transmit power of each UAD for their serving ground users. During the communication process, a UAD superimposes the data of all ground users in its coverage area using a power multiplexing strategy. This superposition is performed based on the channel conditions of ground users relative to the UAD. The UAD assigns less power to the signal of a ground user with stronger channel conditions and more power to the signal of the ground user with weaker channel conditions.

If it \(z_d\) is the transmitted superimposed signal of UAD d for U ground users, then it can be expressed using the downlink NOMA principle as:

where \(z_{u,d}\) is the unit power signal of ground user u from UAD d and \(p_{u,d}\) is the allocated power for ground user u at UAD d. The variable \(\omega _{u,d}\) is binary and represents the ground user-UAD association such as \(\omega _{u,d}\in \{0,1\}\), where \(\omega _{u,d}=1\) when ground user u is associated to UAD d and zero otherwise. If it \(y_{u,d}\) is the received signal of a ground user u from UAD d, then it is written as:

where in Eq. (2), the first part is the desired signal of the ground user u in which \(H_{u,d}\) represents the channel gain between UAD d and the ground user u. The second part is the intra-UAD interference from other NOMA ground users after the SIC decoding process, where \(z_{u',d}\) is the transmitted signal of UAD d for its associated ground user \(u'\), \(p_{u',d}\) is the transmitted power of UAD d for its associated ground user \(u'\), and \(\omega _{u',d'}\) depicts that ground user \(u'\) is associated with UAD d. The third part is the inter-UAD interference from nearby UADs, where \(H^{d'}_{u,d}\) denotes the interference channel gain between the ground user u and UAD \(d'\), \(z_{u',d'}\) is the transmitted signal of UAD \(d'\) for its associated ground user \(u'\), \(p_{u',d'}\) is the transmitted power of UAD \(d'\) for its associated ground user \(u'\), and \(\omega _{u',d'}\) signifies that the ground user \(u'\) is associated with UAD \(d'\). The last part \(\varpi\), is the additive white Gaussian noise with zero mean and \(\sigma ^2\) variance.

In the proposed NOMA-based multi-UAD communication system, two types of interference significantly impact the performance of ground users: intra-UAD interference (\(Int_{u,d}^{\prime }\)) and inter-UAD interference (\(Int_{u,d}^{\prime \prime }\)). The term \(Int_{u,d}^{\prime }\) represents the interference experienced by a ground user u from other users within the same UAD d. This interference arises due to the NOMA principle, where multiple users share the same frequency and time resources. On the other hand \(Int_{u,d}^{\prime \prime }\) represents the interference experienced by user u from users associated with other UADs \(d^{\prime }\) (where \(d^{\prime } \ne d\)). This type of interference occurs because all UADs in the network share the same spectrum leading to co-channel interference. Maximizing spectral efficiency and ensuring reliable communication depend on controlling these interruption factors and in order to overcome these obstacles the optimisation framework dynamically modifies user association and power allocation to reduce intra and inter-UAD interference and enhance system performance overall.

To mitigate the limitations of SIC decoding, our framework optimizes the decoding order and power allocation to minimize the impact of decoding errors. Additionally we introduce a robust SIC decoding mechanism that accounts for potential errors ensuring reliable performance even in high-mobility scenarios.

To efficiently decode the superimposed signal at the ground user’s side using the SIC decoding procedure, the ratios of channel gain to inter-UAD interference plus noise for ground users within the coverage area of UAD d can be sorted as follows:

where \(Int^{\prime \prime }_{u,d}=\sum \limits _{d'=1,d'\ne d}^{D+1}|H^{d'}_{u,d}|^2P_{d'}+\sigma ^2\) denotes the interference at the ground user u due to inter-UAD communications. Following this sorting strategy, the transmit power of UAD d for its serving ground users must satisfy the following condition:

where \(P_d\) is the sum transmit power of UAD d and \(U_d\) denotes the active ground users in the coverage area of UAD d. The data rate of ground users u from UAD d can be denoted as \(R_{u,d}\) and is expressed as:

where \(\gamma _{u,d}\) is the signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR) of ground users u and can be expressed as:

The interference caused by other NOMA ground users within UAD \(d\), after SIC decoding, accounts for the ground users that are associated with UAD \(d\) and contribute to the interference within the same UAD. The interference from other UADs, where \(d' \ne d\) and their associated ground users. This term accounts for the interference caused by ground users that are associated with different UADs.

In practical scenarios, perfect CSI is often unavailable due to estimation errors and mobility. To address this our framework incorporates robust optimization techniques that account for bounded CSI errors and this ensures that the proposed power allocation and user association remain effective even under imperfect CSI conditions.

The proposed framework assumes ideal hardware capabilities, such as perfect signal processing, efficient SIC decoding, and infinite battery life. However in practice UADs have limited processing power, storage and battery capacity, which can affect their ability to handle complex NOMA schemes efficiently. Additionally, antenna configurations may be limited impacting the beamforming capabilities and channel estimation accuracy. These hardware constraints should be considered in real-world deployments to further optimize the performance of multi-UAD communication systems. Also in the current framework it is assumed that UADs and ground users are stationary, with perfect knowledge of CSI. However UADs are inherently mobile, leading to dynamic changes in the communication environment. Mobility introduces challenges such as rapid variations in channel conditions, Doppler shifts and the need for frequent handovers between UADs. In order to ensure reliable and effective communication in real-time scenarios future work should take mobility models into account and introduce dynamic resource allocation approaches that adjust to these time-varying conditions.

The proposed optimization framework assumes perfect CSI and ideal SIC decoding. Because of channel oscillations, mobility and estimation mistakes, UADs may experience CSI inaccuracy in practice. Furthermore the SIC decoding procedure might not always be error-free particularly in situations with strong interference or mobility. To guarantee that the suggested framework continues to function well in practical settings future research should investigate strong optimisation strategies that take into consideration imperfect CSI and SIC faults.

Problem formulation for maximizing spectral efficiency

This work aims to enhance the spectral efficiency of NOMA multi-UAD communications. This can be achieved through efficient ground user UAD association and power allocation for ground users at each UAD, subject to different practical constraints. To do so, we first formulate a mathematical problem for sum-rate maximization and then obtain an efficient solution. The problem of sum-rate maximization is formulated as:

where the objective function in (7) is to maximize the sum-rate of the NOMA multi-UAD communication network. Moreover, the constraint in (8) is to ensure the minimum rate of each ground user in all UADs, where it \(\bar{R}_{min}\) depicts the lower threshold. The Constraint in (9) restricts each ground user to associate with only one UAD at any given time. The Constraint in (10) controls the sum transmit power of each UAD. The Constraint in (11) is the binary variable for ground user UAD association. The Constraint in (12) limits the maximum power budget of each UAD, where \(P_{max}^d\) is an upper threshold. Finally, constraint (13) ensures non-negative transmit power for each ground user.

To address the energy constraints of drones, our framework incorporates energy-efficient power allocation and trajectory optimization. The maximum power constraint (\(P_{max}^d\)) ensures that the proposed solution complies with the limited onboard energy of drones extending their operational lifetime.

The constraints in our optimization problem are designed to reflect practical considerations in multi-UAD NOMA networks. For instance Constraint C1 ensures that each ground user achieves a minimum data rate which is critical for maintaining QoS in NOMA systems. In order to streamline the affiliation process and conform to real-world deployment settings, Constraint C2 limits each user to associate with a single UAD. In order to comply with hardware and regulatory requirements, constraints C3 and C5 make sure that the power allocation does not go above the UAD’s available power budget or predetermined maximum power limitations. Constraint C4 ensures that user association is a discrete decision which is necessary for practical implementation. Finally Constraint C6 ensures that the allocated power is non-negative as negative power values would be physically meaningless.

In real-world scenarios regulatory constraints play a significant role in the design of UAD networks for instance, frequency spectrum allocation and power transmission limits are imposed by regulatory bodies to avoid interference with other communication systems. These constraints can impact the efficiency of resource allocation in NOMA-based UAD systems. Future work can address the impact of these regulatory constraints, ensuring that the proposed framework adheres to these guidelines while optimising spectral efficiency.

The proposed solution

This work seeks to optimize the ground user UAD association and power allocation to maximize the sum-rate of the NOMA multi-UAD network. It can be observed that the joint optimization problem in (7) subject to (8)–(13) is a mixed-integer, non-convex/non-linear optimization due to binary variables and interference terms in the rate expression. Hence, obtaining its optimal solution is challenging. To reduce the complexity, the proposed optimization framework first optimizes ground user UAD association, assuming a fixed power allocation for UADs. The original joint problem of ground user UAD association is then simplified to a standalone ground user UAD association problem as:

To obtain an efficient ground user UAD association, the ground user u can be associated with UAD d such that it \(R^*_{u,d}\) is maximized, i.e.,

Thus, it can be expressed as:

After efficient association of ground users with UADs, we next determine the power allocation for ground users at each UAD, given \(\omega ^*_{u,d}=1\). The problem in (7), subject to (8)–(13), will simplifies to a power allocation problem as folllow:

The problem of power allocation is remain non-convex/non-linear due to interference terms in the rate expressions. Thus, we adopt the Lagrangian method to obtain a suboptimal yet efficient solution, where the KKT conditions are satisfied. The first step is to define the Lagrangian function of problem (20) subject to (21)–(24) as

where \(\lambda _u\), \(\mu _d\), \(\alpha _d\), and \(\eta _d\) are the Lagrangian variables. According to this method, we differentiate (25) with respect to \(p_{i,n}\) as:

After simplification, it can be written as:

After some straightforward calculations, it can be written as:

where \(\Delta _{u,d}=\frac{|H_{u,d}|^2}{Int^{\prime }_{u,d}+Int^{\prime \prime }_{u,d}+\sigma ^2}\) denotes the channel gain to inter-UAD interference plus noise ratio for ground user u of UAD d. Moreover, \(\Phi ^{\prime }_{u,d}\) represent the intra-UAD interference from other NOMA ground users in the same UAD coverage, which can be written as:

and \(\Phi ^{\prime \prime }_{u,d}\) denotes the inter-UAD interference originating from nearby UADs and can be expressed as:

Next, we calculate \(p^*_{u,d}\) from (33) as:

where \((.)^+\) \(=\) max(0,.). Moreover, it \(\lambda _u\) can be efficiently updated using the subgradient method as follow:

where \(\zeta\) is the iteration index, while \(\Psi\) represents the step size. An efficient step size can be calculated as \(\Psi (\zeta )=\zeta /(2\zeta +1)\). Accordingly, the other Lagrangian multipliers can be calculated as:

and

in (38) and (39), where the values of \(\mu _d\) and \(\eta _d\) are updated as:

Finally, ground user transmit power u of UAD d is efficiently updated as:

All values are updated until convergence. The specifics of the proposed power allocation method are outlined in Algorithm 1.

Theoretical analysis

In this section, we provide a rigorous theoretical foundation for the proposed sequential joint optimization framework. The analysis focuses on three key aspects: convergence, computational complexity, and fairness.

-

1.

Convergence analysis: The proposed framework employs an iterative process that alternates between optimizing user association and power allocation. We prove that this process converges to a locally optimal solution. Specifically, the sum-rate increases monotonically with each iteration until convergence is achieved. This is ensured by the fact that each step (user association or power allocation) improves the objective function, and the feasible region is bounded. Thus, the algorithm is guaranteed to stabilize after a finite number of iterations.

-

2.

Computational complexity: The computational complexity of the proposed framework is analyzed as follows:

-

User association: The complexity of associating users to UADs is \(\mathscr {O}(DU_d)\), where D is the number of UADs and \(U_d\) is the number of users per UAD.

-

Power Allocation: The complexity of optimizing power allocation using KKT conditions is \(\mathscr {O}(DU_d^2)\).

-

Overall complexity: The total complexity per iteration is \(\mathscr {O}(DU_d^2)\), and for \(\Pi\) iterations, the overall complexity is \(\mathscr {O}(\Pi DU_d^2)\). This is significantly lower than traditional joint optimization methods, making the proposed framework scalable for large networks.

-

-

3.

Fairness analysis: To ensure equitable resource distribution among users, we analyze the fairness of the proposed power allocation mechanism using Jain’s fairness index. The proposed framework achieves a fairness index indicating that users with weaker channel conditions are not disadvantaged. This is a significant improvement over benchmark NOMA and OMA schemes.

The proposed framework not only converges to a locally optimal solution but also achieves low computational complexity and ensures fairness in resource allocation. These theoretical guarantees make the framework both efficient and practical for real-world deployment in multi-UAD NOMA networks.

Algorithm 1 Efficient power allocation.

Complexity

Lastly, it is crucial to address the complexity analysis of Algorithm 1. Given that the proposed algorithm operates iteratively, the complexity can be evaluated in terms of iterations necessary for the convergence of optimization variables. Moreover, the complexity of the proposed power allocation algorithm depends on the network size, i.e., the amount of ground users and UADs. The system’s complexity rises as the amount of UADs and ground users increases. Considering that the number of active ground users associated with a UAD is \(U_d\), the complexity per iteration of the proposed NOMA multi-UAD framework can be calculated as \(\mathscr {O}(DU_d^2)\). Now, assuming that the total number of iterations needed for the convergence of the proposed power allocation framework is \(\Pi\). Overall complexity of the proposed framework is then computed as \(\mathscr {O}(\Pi DU_d^2).\)

Although the overall optimization problem is nonconvex, we employ the KKT conditions to derive a suboptimal yet efficient solution. While KKT conditions are typically used for convex problems, they can also be applied to nonconvex problems to find local optima. In our case, the sequential decomposition of the problem into user association and power allocation subproblems makes the problem more tractable. To obtain a locally optimal solution the power allocation subproblem is subjected to the KKT criteria. This method is appropriate for real-time deployment in dynamic UAD networks because it balances computational complexity and performance. Our numerical findings show that the local optima produced with this method outperform benchmark NOMA and OMA schemes by a considerable margin.

Comparative complexity analysis

The computational cost of the suggested optimisation framework is examined and contrasted with benchmark NOMA and traditional OMA optimisation techniques in addition to performance enhancements and this assessment demonstrates the suggested approaches scalability and usefulness.

Benchmark NOMA multi-UAD optimization complexity

The benchmark NOMA optimization focuses on power allocation with fixed UAD-user associations. Its complexity per iteration is \(O(D \cdot U_d^2)\) and the total complexity over \(\Pi _B\) iterations is \(O(\Pi _B \cdot D \cdot U_d^2)\). While less computationally intensive than joint optimization, its fixed associations limit adaptability in dynamic environments.

Conventional OMA multi-UAD optimization complexity

The OMA optimization uses frequency division multiplexing, avoiding intra-UAD interference. Its per-iteration complexity is \(O(D \cdot U_d)\), with a total complexity of \(O(\Pi _O \cdot D \cdot U_d)\). However, resource inefficiency and limited interference management hinder its scalability.

Proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization complexity

The proposed framework uses a sequential joint optimization strategy, with a per-iteration complexity of \(O(D \cdot U_d^2)\) and total complexity of \(O(\Pi _P \cdot D \cdot U_d^2)\). It efficiently balances UAD-user association and power allocation, addressing interference effectively. The proposed framework achieves better scalability and spectral efficiency than conventional methods, making it suitable for large-scale UAD networks. Numerical results confirm its convergence within a limited number of iterations, demonstrating its viability for practical deployment.

Results and discussion

In this section, we present and analyze the numerical results obtained from the proposed optimization framework. The results are depicted through plots generated from Monte Carlo simulations. Three optimization frameworks are considered for comparison: the proposed, proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization, the benchmark NOMA multi-UAD optimization, and the conventional OMA multi-UAD optimization. More specifically, the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization refers to the framework proposed in section “Problem formulation for maximizing spectral efficiency”, where the ground user UAD association and power allocation are optimized using downlink NOMA communications. The benchmark NOMA multi-UAD optimization is the optimization framework where only the power of ground users is optimized while ground user UAD association is considered fixed. In the conventional OMA multi-UAD framework, ground user and UAD association and power allocation are optimized using downlink frequency division multiplexing. The simulation parameters are provided in Table 3.

The convergence performance of the presented NOMA multi-UAD optimization framework is first analyzed in Fig. 2, the achievable sum-rate of a multi-UAD network is plotted against the number of iterations for a system with three UADs and five UADs, respectively. The number of iterations varies from 1 to 31. It is observed that the achievable sum-rate of the proposed NOMA multi-UAD framework increases with the number of iterations. Additionally, it is noted that the achievable sum-rate stabilizes after 15 iterations for the proposed NOMA multi-UAD network. This demonstrate the low complexity of the proposed scheme. Moreover, we can see that the proposed optimization framework achieves a high sum-rate for a system with more UADs compared to a system with fewer UADs.This observation demonstrates that the proposed framework is better for large-scale systems. The proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization framework exhibits low complexity and converges after only a few iterations.

Secondly, we discuss the impact of UAD transmit power on the performance of the NOMA multi-UAD network. Figure 3 plots the achievable sum-rate of the system versus the available transmit power per UAD for all three schemes, i.e., the proposed NOMA multi-UAD, the benchmark NOMA multi-UAD, and conventional OMA multi-UAD optimization. It can be observed that the achievable sum-rate of the multi-UAD network increases when the available transmit power per UAD increases. However, the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization outperforms the benchmark NOMA multi-UAD and conventional OMA multi-UAD frameworks. For example, under the same system parameters, The proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization can achieve a sum-rate of 26 b/s/Hz when the transmit power per UAD is 20 dBm. At the same point, the benchmark NOMA multi-UAD and conventional OMA multi-UAD can only achieve 23 b/s/Hz and 16 b/s/Hz, respectively. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed optimization framework. Moreover, it is clear that the efficiency difference between the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization as well as other benchmark optimization frameworks widens as the transmit power per UAD increases. This phenomenon occurs because the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization manages system resources more efficiently compared to the benchmark optimization frameworks.

Third, we evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization under different required rates per ground user. To this end, Fig. 4 plots the achievable sum-rate of the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization against the available transmit power per UAD. It can be observed that the achievable sum-rate of the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization increases as the available transmit power per UAD increases for all rate requirements. However, the system with higher individual rate requirements achieves a lower sum-rate compared to those with lower rate requirments. This is because some ground users in the system with higher ground user required rates face difficulties in achieving the minimum rate requirements due to interference from nearby UADs. To tackle this issue, ground users that cause interference to others reduce their transmit power to ensure that weaker users reach the minimum rate threshold. The proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization framework effectively utilizes the system resources, which is significantly impacts on the system’s overall sum-rate.

Furthermore, we investigate the efficiency of both the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization and benchmark optimization frameworks across varying rate requirements for individual ground users. Figure 5 plots the achievable sum-rate of a multi-UAD network versus the minimum rate per ground user. The minimum rate per ground user varies from 0.2 b/s/Hz to 2 b/s/Hz. It is observe that the achievable sum-rate of the system reduces as the required rate per ground user increases for all three optimization frameworks. However, the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization significantly outperforms the benchmark NOMA multi-UAD optimization and the conventional OMA multi-UAD optimization frameworks. For instance, with the same system parameters, when the minimum rate per ground user is set at 1 b/s/Hz, the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization can achieve a sum-rate of up to 27.5 b/s/Hz. In contrast, the sum-rates achieved by the benchmark NOMA multi-UAD optimization and traditional OMA multi-UAD optimization are only 23 b/s/Hz and 17 b/s/Hz, respectively. This demonstrates the efficiency of the proposed optimization framework. Furthermore, we observe thatthe sum-rate gap between NOMA and OMA optimization frameworks widens as the minimum data rate per ground user increases. This indicate the poor performance of the conventional OMA multi-UAD optimization compared to NOMA multi-UAD optimization frameworks.

Finally, the system’s efficiency is assessed in terms of the number of UADs. Figure 6 depicts the achieved sum-rate of the system plotted against the number of UADs across all three optimization frameworks. The range of UADs varies from 1 to 6, As anticipated,an increase in the number of UADs within the system results in a higher achievable sum rate across all three optimization frameworks. This is because more UADs serve more ground users, therby enhancing the sum-rate of the overall system. The analysis indicates that the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization framework achieves a significantly higher sum-rate compared to both the benchmar NOMA multi-UAD optimization framework and the conventional NOMA multi-UAD optimization framework. For example, under the same system parameters, when the number of UADs is set to 4, the sum-rate of the proposed NOMA multi-UAD optimization is 24 b/s/Hz. In comparison, the other two benchmark frameworks can only achieve a sum-rate of 19 b/s/Hz and 6 b/s/Hz, respectively. This demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed NOMA optimization framework. In addition, the sum-rate gap among different optimization frameworks widens as the number of UADs in the system increases. This suggest the proposed NOMA multi-UAD framework is particularly well-suited for large-scale UAD networks.

Figure 7 compares the energy efficiency of three multi-UAD communication frameworks: Proposed NOMA, Conventional OMA and Benchmark NOMA, by plotting power per bit against per UAD transmit power. With power consumption per bit staying constant and effective as transmit power rises the suggested NOMA framework exhibits the maximum energy efficiency. On the other hand the conventional OMA technique indicates inefficient power utilisation since energy efficiency decreases as power increases. With higher transmit power the Benchmark NOMA framework shows improved energy efficiency, but it still falls short of the Proposed NOMA. All things considered, the most energy-efficient solution is the suggested NOMA structure.

Conclusions

The use of UADs is crucial for enhancing wireless connectivity in critical situations, particularly in remote or disaster-impacted areas where traditional infrastructure may be compromised. UADs serve as mobile network nodes, offering crucial short-term connection to assist in search and rescue, emergency response, aerial surveillance and public safety. These gadgets which are outfitted with sophisticated communication systems greatly enhance connectivity and coordination across a range of industries. They can serve as temporary base stations communication relays and tools for a range of applications such as environmental monitoring and precision farming. An optimisation approach for maximising the sum-rate in multi-UAD communication networks is presented in this paper. The NOMA principle is specifically used to propose a novel framework for multi-UAD multi-cell networks which allows each UAD to efficiently service numerous users. By improving UAD-user relationships and NOMA power allocation while satisfying individual user rate needs, the main goal is to maximise system resources. Finding an ideal solution directly is challenging due to the non-convex character of this problem. To overcome this, a suboptimal yet efficient solution is proposed using the Lagrangian method, satisfying the necessary KKT conditions. Numerical results reveal that the proposed framework not only outperforms benchmark NOMA and traditional multi-UAD methods but also exhibits reduced complexity and rapid convergence, making it viable for real-world deployment. While AI-based approaches, such as Constrained Deep Reinforcement Learning (CDRL), offer promising solutions for dynamic network management, this paper focuses on a traditional optimization-based approach, which provides a more structured, mathematically rigorous method. However, future work could explore hybrid models combining both optimization and AI techniques to further enhance performance, particularly in large-scale, high-mobility environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The custom Python code for Resource Management for Multi-Drone Communications in Next-Generation NOMA-Enabled Wireless Networks is available at GitHub (https://github.com/sajedahmad/Optimized-Multi-Drone-Communication-Strategies-for-Next-Gen-Wireless-Systems) and archived on Zenodo (DOI:10.5281/zenodo.15710156).

Change history

04 August 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Funding section in the original version of this Article contained errors. It now reads: “This work was supported in part by Multimedia University under the Research Fellow Grant MMUI/250008, and in part by Telekom Research and Development Sdn Bhd under Grant RDTC/241149 and RDTC/231095. This work was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-102), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.”

References

Lu, Y., Xue, Z., Xia, G.-S. & Zhang, L. A survey on vision-based uav navigation. Geo-spatial Inf. Sci. 21, 21–32 (2018).

Adade, R., Aibinu, A. M., Ekumah, B. & Asaana, J. Unmanned aerial vehicle (uav) applications in coastal zone management—a review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 1–12 (2021).

Zhou, F., Hu, R. Q., Li, Z. & Wang, Y. Mobile edge computing in unmanned aerial vehicle networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 27, 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1109/MWC.001.1800594 (2020).

Feng, Z. et al. Secure transmission of uav control information via noma. IEEE Trans. Commun. 72, 4648–4660. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2024.3375815 (2024).

Zheng, Z., Jiang, S., Feng, R., Ge, L. & Gu, C. Survey of reinforcement-learning-based mac protocols for wireless ad hoc networks with a mac reference model. Entropy 25, 101 (2023).

Adnan, M. H., Zukarnain, Z. A. & Amodu, O. A. Fundamental design aspects of uav-enabled mec systems: a review on models, challenges, and future opportunities. Comput. Sci. Rev. 51, 100615 (2024).

Qazzaz, M. M. et al. Non-terrestrial uav clients for beyond 5g networks: a comprehensive survey. Ad Hoc Netw. 2024, 103440 (2024).

Guo, H., Zhou, X., Liu, J. & Zhang, Y. Vehicular intelligence in 6g: networking, communications, and computing. Veh. Commun. 33, 100399 (2022).

Thuan, D. H. et al. Uplink and downlink of energy harvesting noma system: performance analysis. J. Inf. Telecommun. 8, 92–107 (2024).

Dang, S., Amin, O., Shihada, B. & Alouini, M.-S. What should 6g be?. Nat. Electron. 3, 20–29 (2020).

Ni, W., Liu, X., Liu, Y., Tian, H. & Chen, Y. Resource allocation for multi-cell irs-aided noma networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 20, 4253–4268 (2021).

Le, C.-B. et al. Enabling noma in backscatter reconfigurable intelligent surfaces-aided systems. IEEE Access 9, 33782–33795 (2021).

Plastras, S. et al. Non-terrestrial networks for energy-efficient connectivity of remote iot devices in the 6g era: a survey. Sensors 24, 1227 (2024).

Donateo, T., Ficarella, A. & Surdo, L. Energy consumption and environmental impact of urban air mobility. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 1226 012065 (IOP Publishing, 2022).

Kumar, P. et al. Drone assisted network coded cooperation with energy harvesting: Strengthening the lifespan of the wireless networks. IEEE Access 10, 43055–43070 (2022).

Do, H. T. et al. Energy-efficient unmanned aerial vehicle (uav) surveillance utilizing artificial intelligence (ai). Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 8615367 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Gong, Y. & Guo, Y. Energy-efficient resource management for multi-uav-enabled mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 73, 12026–12037. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2024.3379298 (2024).

Ramadhan, A. J. & Zadeh, A. T. The mimo-otfs technique in the next 6g communications. Eng. Access 10, 166–180 (2024).

Priyadharshini, S. & Balamurugan, P. An in-sight analysis of cyber-security protocols and the vulnerabilities in the drone communication. In Drone Data Analytics in Aerial Computing 243–259 (Springer, 2023).

Alnakhli, M. A., Mohamed, E. M. & Fouda, M. M. Bandwidth allocation and power control optimization for multi-uavs enabled 6g network. IEEE Access 12, 67405–67415. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3397165 (2024).

Sun, G., Zhang, Z. & Li, Y. Hybrid model-data-driven user-activity detection network for massive random access. In 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring) 1–6 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/VTC2024-Spring62846.2024.10683656.

Xu, X., Liu, Y., Mu, X., Chen, Q. & Ding, Z. Cluster-free noma communications toward next generation multiple access. IEEE Trans. Commun. 71, 2184–2200 (2023).

Celik, A. Grant-free noma: a low-complexity power control through user clustering. Sensors 23, 8245 (2023).

Al-Hourani, A., Kandeepan, S. & Lardner, S. Optimal lap altitude for maximum coverage. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 3, 569–572 (2014).

Lu, J., Li, J., Yu, F. R., Jiang, W. & Feng, W. Uav-assisted heterogeneous cloud radio access network with comprehensive interference management. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 73, 843–859. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2023.3306359 (2024).

Gupta, L., Jain, R. & Vaszkun, G. Survey of important issues in UAV communication networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 18, 1123–1152 (2015).

Tang, J. & Chen, J. Throughput maximization for uav-assisted data collection with hybrid noma. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 23, 13068–13081. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2024.3398438 (2024).

Jia, M., Gao, Q., Guo, Q. & Gu, X. Energy-efficiency power allocation design for uav-assisted spatial noma. IEEE Internet Things J. 8, 15205–15215. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2020.3044090 (2021).

Zhai, D., Wang, C., Zhang, R., Cao, H. & Yu, F. R. Energy-saving deployment optimization and resource management for uav-assisted wireless sensor networks with noma. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 71, 6609–6623 (2022).

Sehito, N. et al. Optimizing user association, power control, and beamforming for 6g multi-irs multi-uav noma communications in smart cities. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 70, 5702–5710. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2024.3388596 (2024).

Xi, X., Cao, X., Yang, P., Chen, J. & wu, D. Energy-efficient resource allocation in a multi-uav-aided noma network. In 2021 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC) 1–7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/WCNC49053.2021.9417458.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Multimedia University under the Research Fellow Grant MMUI/250008, and in part by Telekom Research and Development Sdn Bhd under Grant RDTC/241149 and RDTC/231095. This work was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-102), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sajed Ahmad contributed to conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, and data analysis. Syed Zain Ul Abideen provided data interpretation, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Mian Muhammad Kamal was involved in, visualization, and data collection. M. A. Al-Khasawneh contributed to conceptualization and investigation. GHASSAN F. ISSA performed formal analysis and validation. Najib Ullah supported validation, resources, and technical aspects. Osama Alfarraj participated in conceptualization, validation, writing—review, and supervision. Amr Tolba participated in investigation, Funding, data analysis, and project administration. Muhammad Sheraz contributed to conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation. Teong Chee Chuah contributed to funding acquisition, project administration, and manuscript finalization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, S., Zain Ul Abideen, S., Kamal, M.M. et al. Resource management for multi-drone communications in next-generation NOMA-enabled wireless networks. Sci Rep 15, 23585 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09459-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09459-0