Abstract

Groundwater is generally less prone to contamination than surface water; however, pollutant infiltration can occur due to aquifer characteristics and anthropogenic land use (LU) changes. This study presents the first DRASTIC-based groundwater contamination risk (GwCR) framework for stressed aquifers around the Ismailia Canal, a newly developed artificial canal in Egypt. It evaluates the standard DRASTIC, Pesticide DRASTIC, DRASTIC-Lu, and Pesticide DRASTIC-Lu models, along with their modified versions, using Single Parameter Sensitivity Analysis (SPSA) and GIS techniques. SPSA identified the following parameter weights for the pesticide-specific DRASTIC model: D > S > T > A > I > C > R. One- Map Removal Sensitivity Analysis (MRSA) analysis showed the Pesticide DRASTIC model was most sensitive to net recharge (1.36%) and soil media (1.0%), with moderate sensitivity to the vadose zone (0.65%), topography (0.45%), and hydraulic conductivity (0.42%). Excluding key parameters, particularly D, A, and S, caused significant variability, impacting vulnerability assessments. The Pesticide DRASTICSPSA model outperformed others, with 82.6% of groundwater samples, along with relative frequency greater than 0.8 in moderate to very high vulnerability zones. The Pesticide DRASTICSPSA map indicated that 36.21 km², 6.26 km², 19.03 km², 31.0 km², and 13.09 km² of the study area were in very high, high, moderate, low, and very low susceptibility zones, respectively. The high and very high vulnerability zones were primarily located in the northern and southern regions of the Ismailia Canal, where the protective clay layer is absent and shallow groundwater and sandy vadose zones prevail. The very high vulnerability area increased from 27.3 km² in the original DRASTIC model to 30.52 km² under the Pesticide DRASTICSPSA model. These findings apply to other regions with similar hydrogeological and socio-economic conditions, offering insights for future freshwater canal system development in Egypt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustainable development challenges often stem from the availability and suitability of freshwater resources, particularly when surface water sources are limited or polluted1,2. In North African developing nations, particularly arid regions like Egypt, the scarcity of freshwater has heightened the focus on utilizing groundwater to meet diverse needs3. While groundwater is generally more accessible, reliable, and less prone to contamination compared to surface water, it is still susceptible to pollutants that can degrade its quality4,5,6,7,8,9. Additionally, population growth has amplified the need to identify and secure vital groundwater reserves; however, these resources are increasingly threatened by salinization driven by rising urban water demand10. For example, contaminants originating from unregulated agricultural and aquaculture practices have led to the degradation of both surface and groundwater quality11. Consequently, groundwater contamination remains a critical issue in rapidly developing regions, where economic growth often clashes with environmental protection, jeopardizing water quality and availability3,10,12.

Studies have extensively examined chemical pollutants in groundwater13,14, revealing significant impacts from human activities, including agricultural runoff, industrial effluents, improper waste disposal, and inadequate wastewater treatment15. Natural hydrological and geological conditions can further exacerbate aquifer contamination, increasing groundwater vulnerability16. Shallow aquifers are especially prone to pollution, highlighting the need for effective protection strategies17,18. These stressors threaten ecosystem integrity, necessitating a balance between current water demands and resource sustainability19. Therefore, maintaining a sustainable groundwater supply and efficient irrigation practices is essential for food security and long-term economic and social development.

Groundwater vulnerability assessments are essential for managing aquifer risks, as they indicate contamination susceptibility based on hydrogeological characteristics and overlying strata20,21. These assessments evaluate the likelihood of contaminants reaching the water table by considering geological structure, aquifer hydraulics, and soil properties10,22,23. Vulnerability maps visually classify areas to aid in groundwater protection and sustainable management. Such assessments support planners and decision-makers in socio-economic planning for urban development, land reclamation, and industrial projects24,25,26. Using the DRASTIC system, the groundwater vulnerability of an aquifer can be systematically assessed based on its hydrogeologic settings that represent the major geologic and hydrologic characteristics of the aquifer24.

Various index-based methods have been globally employed to assess groundwater contamination risk (GwCR), including DRASTIC24, GOD27, SINTACS28, and GALDIT29. Among these, DRASTIC is one of the most widely applied and adaptable methods for evaluating groundwater vulnerability across diverse hydrogeological contexts30,31,32,33. By integrating geological, geomorphological, and hydrogeological factors, DRASTIC offers a comprehensive analysis34. Specifically, it assesses groundwater vulnerability using seven variables: Depth to groundwater (D), Net Recharge (R), Aquifer media (A), Soil media (S), Topography (T), Impact of the vadose zone (I), and Hydraulic Conductivity of the aquifer (C), particularly in urbanized riverine areas17,35. DRASTIC parameters are typically scored and weighted using multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) based on expert judgment within Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to evaluate groundwater vulnerability31. GIS is effective for implementing DRASTIC indexes, as it facilitates the integration of data layers, adjusts classification parameters, and manages spatial data for analysis and presentation36,37,38,39. In regions characterized by intensive agricultural activity, such as riverine landscapes, modified DRASTIC variants—such as pesticide DRASTIC—assign greater weights to parameters like soil type and slope (Banton and Villeneuve, 1989). The flexibility of the DRASTIC model allows for the calibration of weights and ratings to reflect local geological and hydrological conditions, thereby enhancing its accuracy and applicability to specific study areas33.

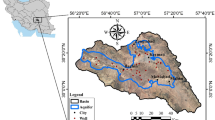

The Eastern Nile Delta region in Egypt holds substantial socio-economic and environmental significance, functioning as a vital development corridor within the densely populated Nile Valley and Delta40. The Quaternary aquifer, depicted in Fig. 1A, serves as the principal source of groundwater in this area, supporting a wide range of human activities. The completion of the Ismailia Canal in 1862 marked a pivotal advancement, supplying essential irrigation and potable water resources to Egypt41. In recent decades, the newly urbanized zones adjacent to the Ismailia Canal in the eastern Delta have experienced intensive irrigation and agricultural expansion, characterized by the widespread application of fertilizers and pesticides42. Additionally, the continued reliance on traditional flood irrigation techniques has exacerbated the vulnerability of groundwater resources, as elevated infiltration rates heighten the potential for contamination42,43,44,45. While previous investigations have largely concentrated on groundwater chemistry, aquifer lithology, and the rising groundwater table, limited attention has been directed toward evaluating groundwater pollution or its susceptibility within this highly anthropogenically influenced setting. Comparable studies from other regions34,36,46, have emphasized the critical role of land use in shaping groundwater quality, demonstrating that varying land use practices and anthropogenic activities contribute to contaminant infiltration in riverine systems46,47,48,49. To address this gap, enhanced versions of the DRASTIC model—such as DRASTIC-Lu and Pesticide DRASTIC-Lu—have been used to incorporate land use (Lu) parameters, thereby improving the assessment of groundwater vulnerability in this stressed riverine canal. Accordingly, the present study futher employs the standard DRASTIC and Pesticide DRASTIC models to evaluate GwCR in the vicinity of the Ismailia Canal, generating vulnerability maps within a GIS-based framework. Furthermore, a comprehensive sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between model input parameters and spatial variables, offering key insights into the model’s robustness and deepening the understanding of the primary factors influencing groundwater vulnerability. This study presents a robust qualitative and quantitative framework for assessing groundwater vulnerability, offering critical support for future planning and development of freshwater canal systems in Egypt under similar hydrogeological and socio-economic conditions. For example, it can inform the design and implementation of artificial agricultural canals within the New Delta megaprojects aimed at expanding agricultural productivity (https://sis.gov.eg/Story/162017/New-Delta-project?lang=en-us, accessed on March 25, 2025). The proposed approach also contributes to mitigating the adverse impacts of anthropogenic activities on groundwater resources.

Study area

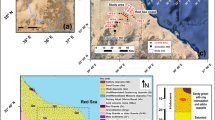

The study area is located in the Eastern Nile Delta, extending along and surrounding the Ismailia Canal, which flows from the River Nile in Cairo Governorate to El Temsah Lake in Ismailia Governorate13,45. It covers an area of approximately 4300 km² and lies between 30°03′ and 30°42′ N and 31°03′ and 32°24′ E (Fig. 1B). The area is bordered by the Suez Canal to the east and the River Nile and Damietta branch to the west, with the southern boundary defined by the desert rolling plains and foothills of the Cretaceous and Tertiary structural exposures (Fig. 2). Most of the region is covered by Quaternary deposits, which are classified into two rock units: the upper Bilqas Formation (Holocene Nile silt and clay) and the lower Mit Ghamr Formation50,51,52,53.

Three stratigraphic cross-sections were constructed using columnar data from 11 wells, ranging in depth from 35 m to 70 m, located around and along the Ismailia Canal, to illustrate the geological setting of the Quaternary Aquifer (Fig. 3). The aquifer is characterized by two types of sediment: a sand-dominated layer in the eastern and southeastern regions, and a clay-dominated layer in the northern and northwestern regions (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3A-B, wells 1, 2, 3, and 4, near the Damietta branch, have upper sections consisting of recent Nile fluvial deposits, while wells 5, 7, 10, and 11 lack clay and are primarily composed of sand deposits from desert and wadi sources. Wells 8 and 9, located away from the Nile but along an ancient river branch (Fig. 3b), show similar sand-dominated characteristics. In the western part of the study area, north of the Ismailia Canal, a clay-dominated sediment layer covers the surface, thinning and disappearing toward the east and northeast, as seen in wells 1, 2, 3, and 4, and vanishing completely in the eastern region (wells 7, 10, and 11) (Fig. 3A). The eastern part, both north and south of the Ismailia Canal, consists entirely of sand-dominated sediments, with potential clay interbeds, particularly near the canal where it crosses an ancient river branch, as shown in wells 5, 8, 9, and 11 (Fig. 3C). Conversely, the western part of the study area features a surface clay-dominated layer overlying sand-dominated sediments, which decreases in thickness toward the south of the Ismailia Canal, as seen in well 5 (Figs. 3B-C). Recharge in the region is derived from three primary sources: rainfall, infiltration from irrigation systems, and the movement of water through the Nile Valley aquifer. The Nile Delta experiences sparse and irregular rainfall during winter, amounting to less than 155 mm annually54. Since 1981, groundwater extraction has increased at an average linear rate of 0.1 billion cubic meters (Bm³) per year, with an accelerated rate of 0.2 Bm³/year observed between 2003 and 201044. Youssef et al.3 reported a substantial decline in terrestrial water storage (ΔTWS) of −86.1 mm between 2005 and 2015, correlating with a reduction in surface water bodies. These trends are linked to extensive aquaculture developments and unauthorized extractions of both surface and groundwater3,55.

Geological cross-sections of the Quaternary Aquifer within the study area are presented as follows: (A) a SW–NE-oriented section approximately parallel to the Ismailia Canal; (B) a SW–NE-oriented section intersecting the Ismailia Canal at two locations; and (C) a SE–NW-oriented section. All cross-sections were constructed using Surfer software (Golden Software, Version 16.6.484), with sea level adopted as the datum plane.

Materials and methods

Table 1 summarizes the datasets used in this research, while Fig. 4 outlines the four-step methodological framework: (1) developing a geodatabase, (2) generating thematic layers from satellite imagery, fieldwork, and archival sources, (3) implementing standard GwCR-based approaches, such as DRASTIC, Pesticide DRASTIC, DRASTIC-Lu, and Pesticide DRASTIC-Lu, (4) refining GwCR maps by incorporating Single Parameter Sensitivity Analysis (SPSA) weights, and (5) validating the models to evaluate their effectiveness in pinpointing groundwater vulnerability in areas experiencing intense urbanization and/or agricultural activities.

Fieldwork and data Preparation

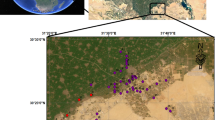

The primary data for this study comprised satellite imagery and field observations, supplemented by an extensive review of region-specific literature (Figs. 5 and 6; Table 1). A single cloud-free Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) scene from 2020 was utilized, alongside a Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Digital Elevation Model (SRTM-DEM) scene covering the study area (Fig. 5A). Both datasets were freely obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) EarthExplorer platform (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/, accessed on 15 May 2024), with their key specifications detailed in Table 1. For image preprocessing, only non-thermal bands (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) of the Landsat 8 scene were selected and spatially subset to delineate the study area (Fig. 1). These bands were subsequently calibrated to surface reflectance using radiometric correction and atmospheric compensation via the Fast Line-of-sight Atmospheric Analysis of Spectral Hypercubes (FLAASH) module within the ENVI 5.1 software environment.

The thematic DRASTIC and DRASTIC-LU rated maps: (A) Depth to water Table, (B) Net Recharge, (C) Aquifer Media, (D) Soil Media, (E) Topography, (F) Impact of Vadose Zone, (G) Hydraulic Conductivity, and (H) LULC. For a 1 to 10 score rating of maps see Table 3.

During 2019, a total of 73 groundwater samples were collected from wells across the study area. Sampling followed the guidelines outlined by56 for water analysis. Groundwater samples were filtered and stored in pre-cleaned, high-density polyethylene one-liter containers with polyethylene closures. The containers were labeled, placed in a cooler, transported to the laboratory, and kept at or below 4 °C until further analysis. Electrical conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS), and pH were measured in situ using a portable Hach 44,600 Conductivity/TDS Meter (3.5-digit, accuracy ± 2%, range up to 20 mS/cm and 20 g/l) and a portable Hach P314 pH meter57. Nitrate (NO3−) concentrations were analyzed using the DX-500 Ion Chromatography system (USA), with an accuracy and precision of 5%. Sampling locations were precisely recorded with GPS equipment, as shown in Fig. 1B. Thematic imagery was converted to 30-meter raster layers in the UTM-WGS 1984, zone 36 N projection using the ArcMap (10.8) package established by ESRI58.

The DRASTIC vulnerability maps were developed by integrating diverse datasets. Seven parameters, listed in Table 1, were generated using ArcMap 10.8. The D—depth to water factor was created based on a water level map from45 using the Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) interpolation tool (Fig. 6A). The R—net recharge map was constructed using annual precipitation, drainage surplus, and evapotranspiration data for the Nile Delta (Fig. 6B), following50. The A—aquifer media map utilized data from59. The S—soil map was derived from soil data provided by60. The T—topographic map was generated using slope percentages from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission-Digital Elevation Model (SRTM-DEM) data (Figs. 5 and 6E). The I factor (Fig. 6F) was determined by comparing61 with60. The C factor map was created by digitizing points from44,62 and applying IDW interpolation (Table 2). The Lu—land use map combined Landsat 8 (L8) with field surveys and high-resolution Google Earth imagery, using 70% of the data for training a maximum likelihood classifier and 30% for testing (Fig. 5B).

Standard DRASTIC models implementation

The DRASTIC parameters were assigned ratings on a scale of 1 to 10, based on the available literature (Table 3), where a rating of 1 represents the least important range or media type, and a rating of 10 corresponds to the most important (Fig. 7). The ranges, ratings, and usage instructions are consistent for both the DRASTIC and Pesticide DRASTIC indices24,36. Similarly, the land use parameter, which has a weight of 5, is categorized into types, with each type assigned a specific rating value as detailed in Table 336,47. Each DRASTIC parameter is given a weight (w) ranging from 1 to 5, indicating its relative significance, where a weight of 1 represents the least significant parameter and a weight of 5 corresponds to the most significant (Table 3). For the Pesticide DRASTIC and Pesticide DRASTIC-Lu, a variant of the DRASTIC system, a second weight is assigned to account for the impact of pesticide use (Table 3), with groundwater pollution potential primarily influenced by pesticides24. The DRASTIC and Pesticide DRASTIC indices were calculated using Eq. (1) while the DRASTIC-Lu and Pesticide DRASTIC-Lu were calculated using Eq. (2).

Where D, R, A, S, T, I and C are the condition vulnerability parameters and Lu is the land use parameter. The subscript ‘r’ is the rating allocated to each range or media type and the subscript ‘w’ is the weight allocated to each parameter24,47,63.

Accuracy assessment of DRASTIC models

Map removal sensitivity analysis (MRSA)

Map Removal Sensitivity Analysis (MRSA) was employed to evaluate the uncertainty level of the model outputs and determine the necessity of incorporating all DRASTIC parameters36,64. This method involves excluding one or more maps from the vulnerability assessment and calculating a variation index (Tables 4 and 5) using Eq. (3), as defined by65.

Where, S is the sensitivity associated with the removal of one map; V is the unperturbed vulnerability index (actual index obtained using all seven maps); V‵ is the perturbed vulnerability index (vulnerability index calculated using a lower number of maps); N is the number of maps used in the unperturbed vulnerability and n is the number of maps used in the perturbed vulnerability.

Single parameter sensitivity analysis (SPSA)

The single parameter sensibility test was performed to check the influence of the DRASTIC parameters on the vulnerability index and compare the theoretical weights of such parameters with their effective weights. The effective weight of a parameter is a function of the other parameters as well as the weight assigned to such parameter by the DRASTIC system. The single parameter sensitivity analysis was carried out using Eq. (4)66.

A Single Parameter Sensitivity Analysis (SPSA) was applied to evaluate the influence of each parameter on the vulnerability model66,67 by comparing the theoretical weights with the Effective (Ef) weights assigned to each parameter (Table 6). The Ef weights were calculated using (4):

Where, \(\:{\text{E}\text{f}}_{\text{w}\:}\)is the effective weight (%); Pri is the rating of the respective parameter; Pwi is the weight of respective parameter; and V is the final vulnerability index25,36,38.

The modified DRASTICSPSA and Pesticide DRASTICSPSA indices were calculated using Eq. (5) while the DRASTIC-LuSPSA and Pesticide DRASTIC-LuSPSA were calculated using Eq. (6).

Where, the subscript ‘r’ is the rating allocated to each range or media type and the subscript ‘Ef’ is the effective weight allocated to each parameter24,47. See Table 7.

Models validation

The accuracy of susceptibility models was assessed using the simple frequency ratio and relative frequency distribution (RFD) methods. A critical step involved evaluating the agreement between polluted groundwater (PGw) samples, with high nitrate concentrations (> 30 mg/L), and areas classified as highly vulnerable68. Accordingly, all generated maps were categorized into five vulnerability levels—very low, low, moderate, high, and very high—using the geometrical classification approach in ArcGIS software69. The RFD method offered another measure of the consistency of the vulnerability maps beyond traditional metrics (Table 8). The consistency of the prediction map was confirmed by calculating the RFD of affected infrastructure occurrences across various GwCR zones70.

Results

Geospatial analysis of DRASTIC parameters and land use

The D factor is a critical determinant for assessing groundwater pollution risk24. Depth values in the study area range from 0 to over 30.5 m (Fig. 6A), with the most common depth interval, 1.5–4.6 m, assigned a rating of 9. The shallowest depth range (0.0–1.5 m), rated at 10, is found primarily along the Ismailia Canal between Al-Abasa and Abu Suwayr. In contrast, the deepest range (22.9–30.5 m), rated at 2, is located north of the Ismailia Canal, between Al-Kasasin, Abu Suwayr, and Al-Salheyia, and extends southward near Al-Abasa (Fig. 7A). The D factor was thus classified into seven categories, with ratings from 1 to 10, as shown in Fig. 7A.

The N factor measures surface water volume per unit area from rainfall and artificial sources71. Recharge rates range from 143 to over 694 mm/year (Fig. 6B) and are classified into two groups (Fig. 7B) based on the DRASTIC rating system24. The aquifer media parameter characterizes the properties of the aquifer materials influencing pollutant attenuation72. The Mit Ghamr Formation, predominantly composed of sand and gravel (Fig. 6C), features high porosity, excellent drainage, and transmission capacity45, earning a rating of 8 (Fig. 7C).

Soil acts as the top layer where weathering occurs, regulating water infiltration and pollutant transport into the vadose zone72. Coarse-grained soils like gravel, gravelly sand, and loose sand (Fig. 6D) provide efficient drainage45, leading to high ratings for pollutant transfer. In contrast, silt and clay soils restrict water flow, reducing contamination risk and receiving lower ratings. The S factor was categorized into four classes with ratings from 3 to 10 (Fig. 7D).

The slope factor (T) influences surface pollutant infiltration into groundwater. Low slopes in the southern and northwestern areas enhance infiltration, increasing groundwater contamination risk (Fig. 6E). The region features low relief with a gentle northward slope and a rolling terrain that rises to a moderately elevated southern plateau73,74. Gentle slopes allow for higher infiltration, while steep slopes decrease water retention and infiltration rates (Nahin et al., 2019). The slope values were rated according to24, as shown in Table 3; Fig. 7E.

The I factor (Fig. 6F) represents the unsaturated zone between the surface and the aquifer24. Hydrogeological units were scored between 3 and 9 (Fig. 7F). The C factor determines groundwater flow rate (Fig. 6G), affecting contaminant dispersion in the aquifer72. High hydraulic conductivity (> 80 m/day) aquifers are rated at 10, while lower-conductivity media receive an 8 (Fig. 7G).

The U factor assesses land cover types and their impact on groundwater quality, particularly in urban settings36,46,75. Eight land cover categories were identified: agriculture, fish farms, urban areas (including roads and cities), drylands, wetlands, surface water bodies, and waterlogged areas (Fig. 5B). Agricultural land dominates, followed by urban areas. The U factor map, using10 rating system, assigns vulnerability scores to land cover types (Table 3). Urban areas have the highest vulnerability score of 10 (Fig. 7H), followed by agriculture (8), wetlands (3), drylands (2), and surface and waterlogged bodies (1).

Standard DRASTIC vulnerability mapping

The seven DRASTIC parameters, along with the land use parameter, were integrated within a GIS environment to calculate the standard DRASTIC, Pesticide DRASTIC, DRASTIC-Lu, and Pesticide DRASTIC-Lu indices. These indices were used to evaluate the potential for groundwater contamination near the Ismailia Canal in the Eastern Nile Delta, considering the hydrogeological characteristics of the area, the effects of pesticide application, and the impact of various land use types. Figure 8 presents a groundwater vulnerability map classified according to DRASTIC index values, where higher values indicate greater groundwater vulnerability24,36,46,66. The five vulnerability classes, namely very low, low, moderate, high, and very high, were provided in square kilometers (Table 8). The DRASTIC index classified approximately 21.94 km², 23.7 km², 19.89 km², 7.17 km², and 27.3 km² of the study area into very low, low, moderate, high, and very high vulnerability zones to pollution risks, respectively (Fig. 8; Table 8). Highly vulnerable areas were mostly concentrated in the southern parts across all maps. However, these zones were significantly reduced in the Pesticide DRASTIC model, especially in the northern region between Al-Salheyia and Al-Kasasin settlements. The inclusion of the Lu factor increased vulnerability from moderate in the standard DRASTIC model too high in the DRASTIC-Lu model, particularly in the western region near the Damietta branch (Figs. 8a-b). Similarly, in the Pesticide DRASTIC model, vulnerability rose from low to moderate in the same western areas upon adding the Lu factor (Figs. 8C-D).

Modified DRASTIC models mapping through sensitivity analysis

The one- MRSA reveals that the D factor is the most influential across all models, with the highest mean variation indices: 2.16% for DRASTIC, 1.73% for pesticide DRASTIC, 1.36% for DRASTIC-LU, and 1.11% for pesticide DRASTIC-LU, due to its high theoretical weight (5). In contrast, the A factor exhibits the lowest mean variation index, contributing no variability (CV% = 0). Although the D map removal results in the greatest variation in the DRASTIC index, other factors like topography, despite its low theoretical weight (1), also significantly affect the index. The R and S factors show mean variation indices of 1.38%, 1.21%, and 1.13%, respectively. The index shows moderate sensitivity to hydraulic conductivity (0.95%) and vadose zone impact (0.89%), even with their high weights (5). For pesticide DRASTIC, the index is highly sensitive to net recharge (1.36%) and soil media (1.0%), with moderate sensitivity to the vadose zone impact (0.65%), topography (0.45%), and hydraulic conductivity (0.42%). In DRASTIC-Lu, the Lu removal results in the highest sensitivity (1.24%), followed by topography (1.10%), while moderate sensitivity is seen for net recharge (0.95%), soil media (0.90%), vadose zone impact (0.70%), and hydraulic conductivity (0.51%). For pesticide DRASTIC-LU, variation indices are generally similar, differing by less than 1%, though net recharge (1.04%) and land use (1.03%) have the highest impact due to their high weights. Moderate sensitivity is noted for soil media (0.79%) and vadose zone impact (0.55%), while hydraulic conductivity (0.40%) and topography (0.23%) show lower sensitivity. Table 5 summarizes variation indices when multiple layers are removed simultaneously. For DRASTIC, the lowest variation occurs with the removal of A and I (mean VI% = 0.86). In pesticide DRASTIC and DRASTIC-Lu, removing A and C layers yields mean VI% values of 0.83 and 0.72, respectively. For pesticide DRASTIC-Lu, the minimum variation is associated with excluding aquifer media and topography (mean VI% = 0.49). Excluding more layers, especially D, R, and S for DRASTIC and pesticide DRASTIC, and D, Lu, and R for DRASTIC-Lu and pesticide DRASTIC-Lu, markedly increases the variation indices, impacting vulnerability assessments.

Statistical SPSA analyses were conducted to evaluate the Ef weight of each DRASTIC parameter, along with the land use, including the DRASTICSPSA, Pesticide DRASTICSPSA, DRASTIC-LuSPSA, and Pesticide DRASTIC-LuSPSA indices. Table 4 presents the theoretical weights assigned by the DRASTIC system, the corresponding theoretical percentages, the mean effective weights, as well as the minimum and maximum values and standard deviations for the relevant vulnerability indices. As shown in Table 4, the calculated effective weights of the DRASTIC parameters differed from their theoretical values. Specifically, for all indices, the effective weights of D, A, T, and C exceeded the theoretical weights assigned by the DRASTIC system. Additionally, the effective weight of the Lu parameter also surpassed its theoretical value. In contrast, the effective weights of the R, S, and I parameters were lower than their theoretical counterparts for the indices examined. Among the parameters, D emerged as the most influential factor in the vulnerability assessment, with mean effective weights of 26.6%, 23.6%, 21.3%, and 19.4%, compared to theoretical weights of 21.7%, 19.2%, 17.9%, and 16.1% for DRASTIC, pesticide DRASTIC, DRASTIC-Lu, and pesticide DRASTIC-Lu, respectively. On the other hand, the R factor exhibited notably lower effective weights, with values of 7.05%, 6.15%, 5.86%, and 5.22% for the respective indices, as compared to theoretical weights of 17.4%, 15.4%, 14.3%, and 12.9%. Based on the mean effective weights (%), the significance of these parameters varied across the indices, as indicated by the following sequences: D > C > I > A > S > R > T for DRASTICSPSA; D > S > T > A > I > C > R for pesticide DRASTICSPSA; D > Lu > C > I > A > S > R > T for DRASTIC-LuSPSA; and D > Lu > S > T > A > I > C > R for pesticide DRASTIC-LuSPSA.

Applying effective weights led to an expansion of the high vulnerability zone in the DRASTICSPSA vulnerability map, reducing the extent of the moderate vulnerability zone in the standard DRASTIC model (Figs. 8A and 9A). Similarly, the very high vulnerability zone in the DRASTIC-LuSPSA map expanded at the expense of the high vulnerability zone in the DRASTIC-Lu model (Figs. 8B and 9B). Additionally, in the Pesticide DRASTICSPSA map, the moderate vulnerability zone increased, reducing the low vulnerability zone’s area in the Pesticide DRASTIC map (Figs. 8C and 9C). Meanwhile, in the Pesticide DRASTIC-LuSPSA map, the high vulnerability zone expanded, decreasing the extent of the moderate vulnerability zone in the Pesticide DRASTIC map (Figs. 8D and 9D). This trend can be attributed to the high-ranking values assigned to the urban and agricultural classes, accompanied by their high effective weights (%). This is likely due to the predominance of agricultural land in the study area, a finding that aligns with the results of Arafa et al.34.

DRASTIC vulnerability validation

Overall, the results indicate that each model produces distinct outcomes regarding the ranges of groundwater vulnerability and their spatial distribution. For example, the standard DRASTIC vulnerability index yields a mean value of approximately 124, whereas the Pesticide DRASTIC-LuSPSA model shows the highest value (Table 7). The spatial distribution of highly vulnerable zones in the standard DRASTIC map generally correlates with that of the Pesticide DRASTIC map. However, differences are observed in the distribution of low and very low vulnerability areas within the DRASTIC-Lu map based on GwCR. Therefore, it is essential to assess the accuracy of these model predictions.

Nitrate concentrations in groundwater are predominantly influenced by human activities, as nitrates do not naturally occur in groundwater but are primarily linked to agricultural practices, such as the use of fertilizers and pesticides76. Nitrates are often used as a reliable indicator of contaminant migration from the surface to the groundwater36,77,78. As depicted in Fig. (9), the highest concentrations of NO3 were observed in the eastern part of the study area and south of the Ismailia Canal (Figs. 8 and 9), where nitrate levels exceeded the guideline value of 30 mg/L for irrigation water79. A GIS-based statistical overlay analysis was conducted to assess the consistency of vulnerability maps with actual polluted points. The validation hypothesis posits that the vulnerability map is reliable if more than 50% of the PGw points fall within at least moderate vulnerability zones (Fig. 10), with a preference for higher susceptibility regions (Youssef et al., 2021). The results showed that 82.6%, 80.09%, 79%, 78.68%, 77.59%, 75.24%, 73.67%, and 43.57% of the PGw samples were situated within the moderate to very high vulnerability zones across the Pesticide DRASTIC SPSA, DRASTIC, Pesticide DRASTIC-Lu, Pesticide DRASTIC-LuSPSA, DRASTICSPSA, DRASTIC-Lu- SPSA, DRASTIC-Lu, and Pesticide DRASTIC maps, respectively (Fig. 10). Of these models, the RFD values notably surpassed 0.8 for DRASTIC and Pesticide DRASTICSPSA, measuring approximately 0.87 and 0.85, respectively, within the moderate to highly vulnerable zones (Table 8). These values indicate the reliability and consistency of the vulnerability assessments, aligning with findings from80,81. Consequently, this study demonstrates the improved accuracy of the Pesticide DRASTICSPSA vulnerability model in refining the GwCR map for the study area.

Discussion

Groundwater contamination is a significant consequence of the water-food nexus in urbanized riverine areas10,17. The DRASTIC index has been used to evaluate groundwater’s intrinsic vulnerability to pollution from human activities, incorporating geological, hydrological, and hydrogeological factors. In the Eastern Nile Delta, intensive human and agricultural activities have substantially degraded groundwater quality, presenting serious environmental and soil risks. While extensive research has focused on water quality for drinking and sanitation11, studies using DRASTIC-based GwCR prediction models remain scarce, particularly in rapidly urbanizing riverine areas. Agriculture, characterized by extensive fertilizer and pesticide use and reliance on traditional irrigation, dominates these regions. To assess pesticide-related pollution risks, this study applied both the DRASTIC model and its pesticide-specific variant, enhancing them by integrating land use as an additional input parameter. When the impact of pesticide application was factored in using the Pesticide DRASTIC index, the values of the DRASTIC index increased, highlighting the potential for pesticide-induced groundwater contamination. Furthermore, the inclusion of the land use parameter in both the DRASTIC and Pesticide DRASTIC indices resulted in higher vulnerability values, emphasizing that groundwater susceptibility to pollution is strongly influenced by land use.

Generating a hazard vulnerability map without proper validation renders it scientifically meaningless82. Among all models, the Pesticide DRASTICSPSA model was the most effective in refining the GwCR map for the study area. This map revealed that approximately 36.21 km², 6.26 km², 19.03 km², 31.0 km², and 13.09 km² of the study area fall within very high, high, moderate, low, and very low susceptibility zones, respectively (Fig. 9C; Table 8). The moderate vulnerability zone, primarily located in the western part of the area, is characterized by a 5–20 m thick silt and clay layer14 that overlies the principal aquifer. In contrast, the high and very high vulnerability zones are concentrated to the north and south of the Ismailia Canal, where the protective clay layer is absent, unsustainable groundwater extraction in regions of moderate vulnerability could heighten pollutions risks. These zones are also distinguished by shallow groundwater depths and a vadose zone composed predominantly of sandy facies8. Notably, the area classified as very highly vulnerable increased from 27.3 km² in the original DRASTIC model to approximately 30.52 km² under the Pesticide DRASTIC-SPSA model (Table 8). These results suggest that soil media play a significant role in groundwater pollution potential. The silt and clay layers throughout most of the study area reduce soil permeability, restrict contaminant migration, and enhance attenuation processes72,81. Additionally, organic matter in the surface silt and clay layers, derived from decayed plant and animal material, aids in pesticide attenuation83,84.

The results are consistent with the outcomes of sensitivity analyses conducted to validate the vulnerability maps. The map removal sensitivity analysis confirmed that the DRASTIC parameters were sufficiently independent and collectively representative for evaluating groundwater pollution vulnerability, with no individual parameter identified as redundant. Among these parameters, SPSA analyses demonstrated that D factors exerted the greatest influence on vulnerability assessment, corroborating the findings of Metwally et al.85. Conversely, the pesticide-specific DRASTIC model exhibited heightened sensitivity to net recharge (1.36%) and soil media (1.0%), along with moderate sensitivity to the impact of the vadose zone (0.65%), topography (0.45%), and hydraulic conductivity (0.42%). This pattern may reflect the influence of the aquifer matrix and the overlying confining layer, as similarly observed in surface water canal systems within the El Fayoum Depression, Western Desert, Egypt, by Gad and El-Hattab86. Additionally, Ouedraogo et al.87 reported that removing the I, D, C, and R parameters in African aquifer systems significantly altered vulnerability mapping outcomes. These findings underscore the importance of including all pesticide DRASTIC parameters in vulnerability assessments to ensure accuracy, in alignment with the SPSA-derived effectiveness weights.

The preceding analysis underscores the synergistic impact of physiographical, hydrogeological, and anthropogenic factors on the aquifer’s potential vulnerability to human-induced contamination. Based on these insights, several key policy recommendations can be advanced to support sustainable groundwater management. First, it is imperative for policymakers to incorporate scientifically robust vulnerability maps—particularly those generated using the Pesticide DRASTIC-SPSA model—into spatial planning and land-use decision-making. These maps effectively classify areas according to varying degrees of susceptibility, ranging from very low to very high, thereby enabling the implementation of targeted mitigation strategies in high-risk zones. For example, in areas of elevated vulnerability adjacent to the Ismailia Canal, stringent regulation of agrochemical use and unsustainable groundwater abstraction is crucial to curbing further deterioration10,13. Consequently, zones identified as highly vulnerable should be prioritized for preventive measures, including the imposition of land-use restrictions and the deployment of protective strategies to safeguard groundwater quality34. These strategies may include the establishment of buffer zones, limitations on pesticide application, and the adoption of modern irrigation techniques designed to minimize contaminant transport via recharge. Furthermore, public awareness initiatives and community-based educational programs focused on sustainable agricultural practices and the implications of groundwater pollution are essential for achieving long-term resilience. This study also introduces a practical and adaptable modeling framework for assessing contamination potential in densely populated regions subjected to diverse anthropogenic pressures. The results not only contribute to informed water and food security planning but also emphasize the need for community engagement to mitigate salinization and associated health risks. This integrated approach offers a transferable methodology for groundwater vulnerability assessment in other regions with comparable hydrogeological and socio-economic settings.

Conclusion

Groundwater contamination is a critical concern in rapidly urbanizing riverine areas, particularly where surface water is scarce or polluted. This study employed the DRASTIC-based GwCR framework to evaluate standard and land use–integrated DRASTIC and Pesticide DRASTIC models, along with their SPSA-optimized variants, to assess groundwater vulnerability around the Ismailia Canal. Findings highlight that agricultural activities—particularly fertilizer and pesticide application—are the primary sources of contamination. The Pesticide DRASTICSPSA model demonstrated superior performance, with 82.6% of PGw samples located in moderate to very high vulnerability zones and an RFD exceeding 0.8, indicating high reliability. This model delineated 36.21 km² as very high, 6.26 km² as high, 19.03 km² as moderate, 31.0 km² as low, and 13.09 km² as very low vulnerability. Highly vulnerable areas are concentrated north and south of the canal, where protective clay layers are absent, groundwater is shallow, and the vadose zone is sandy. Compared to the original DRASTIC model, the very high vulnerability zone expanded from 27.3 km² to 30.52 km². SPSA analysis revealed the following parameter weight hierarchy for the Pesticide DRASTIC model: D > S > T > A > I > C > R. One-MRSA analysis showed highest sensitivity to net recharge (1.36%) and soil media (1.0%), with moderate effects from vadose zone (0.65%), topography (0.45%), and conductivity (0.42%). Omitting key parameters like D, A, and S introduced significant variability. The proposed framework is adaptable to other urban riverine regions with comparable hydrogeological and socio-economic conditions. Future studies should incorporate machine learning–enhanced DRASTIC models, integrating variables such as pumping rates, land cover change, and integrated electrical conductivity (IEC) to improve both qualitative and quantitative groundwater risk assessments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adelana, S. & MacDonald, A. Applied groundwater studies in Africa. IAH Sel. Papers Hydrogeol. P 13, (2008). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203889497

Joseph Omeiza, A. A. L. H. S. N. M. Investigation of groundwater vulnerability to open dumpsites and its potential risk using electrical resistivity and water analysis, Heliyon, p. 9: 13265. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13.

Youssef, Y. M., Gemail, K. S., Atia, H. M., & Mahdy, M. Insight into land cover dynamics and water challenges under anthropogenic and Climatic changes in the Eastern nile delta: inference from remote sensing and GIS data. Sci. Total Environ. pp. 913, 169690 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169690

Li, P. et al. Hydrogeochemical characterization of groundwater in and around a wastewater irrigated forest in the southeastern edge of the Tengger desert, Northwest China. Exposure Health, p. 8 (3), (2016).

Patrick, R., Grant, K. & Bharadwaj, L. Reclaiming Indigenous planning as a pathway to local water security., Water, pp. 11(5), 936. (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11050936.

Salem, Z. & Elsaiedy, G. and E. A., Assessment of the Groundwater Quality for Drinking and Irrigation Purposes in the Central Nile Delta Region, Egypt. A.M. Negm (ed.), Groundwater in the Nile Delta, Hdb. Env. Chem., Springer, Cham, vol. 73, pp. 647–684., (2017).

Salem, Z., Elsaiedy, G. & ElNahrawy, A. Hydrogeochemistry and quality assessment of groundwater under some central Nile Delta villages, Egypt. In: The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry., Springer (Groundwater in the Nile Delta, Berlin, Heid, 2017. (2019).

Salem, Z., Sefelnasr, A. & Hasan, S. As a Water Resources Management Tool, Groundwater Quality Assessment for Irrigation in the Young Alluvial Plain of Western Nile Delta, Egypt, In A. M. Negm and M. El-Rawy (eds.), Earth and Environmental Sciences Library, pp. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12676-5_8.

Alsaeed, R. D., Aldarwish, A. Q., Khouri, L., & Kolluru, V. Response surface modeling of sodium hypochlorite-based manganese oxidation in drinking water, DYSONA-Applied Science, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 334–342, (2025). https://doi.org/10.30493/das.2025.484126

Arafa, N.A., El-Said Salem, Z., Abdeldayem, A.L. et al, advancing deltaic aquifer vulnerability mapping to seawater intrusion A.d human impacts in Eastern nile delta: insights from machine learning A.d hydrochemical perspective. Earth Syst. Environ, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-024-00518-6

Abu Salem, G. K. J. N. I. A. N. A. HS An integrated approach for Deciphering hydrogeochemical processes during seawater intrusion in coastal aquifers. Water 14, 1165. https://doi.org/103390/w14071165 (2022).

Gárfias, J. Assessment of vulnerability and control measures to protect the Salbarua ecosystem from hypothetical spill sites. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-2672-0 (2018).

Salem, Z., Abdelrahman, Kovácˇiková, S. & Badran, O. Use of various statistical techniques to assess the vertical and lateral change in the groundwater chemistry of quaternary aquifer in an irrigated highly populated area. J. King Saud University–Science. 33, 1015562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101556 (2021a).

Salem, Z., ElNahrawy, A., Attiah, A. & Edokpayi, J. Vertical and Spatial evaluation of the groundwater chemistry in the central nile Delta quaternary aquifer to assess the effects of human activities and seawater intrusion. Front. Environ. Sci. p. 10, 961059. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.961059 (2022b).

Poshtegal, M. & Mirbagheri, S. The heavy metals pollution index and water quality monitoring of the Zarrineh river, Iran. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.2113/eeg-1996 (2019).

Abduljaleel, Y. A. M. A. E. A. Enhancing groundwater vulnerability assessment for improved environmental management: addressing a critical environmental concern. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31, 19185–19205 (2024).

M. I. I. Y., M. Z. S. & Tavakoli, Y. M, Sustainable groundwater management using machine Learning-Based DRASTIC model in rurbanizing riverine region: A case study of Kerman province, iran., Water, 16, 19, p. 2748, (2024).

Alhamd, A. D., & Ibrahim, M. A. Unveiling soil and groundwater salinity dynamics and its impact on date palm yield in Southern basrah, Iraq. DYSONA-Applied Sci. 5 (2), 25–32 (2024). https://doi.org/10.30493/das.2024.427608

Abdelhameed, A., Salem, Z. & Osman, O. Sedimentological characteristics of the quaternary groundwater aquifer, Northwestern nile delta, egypt., in. In In: the Handbook of Environmental Chemistry (2017). Groundwater in the Nile Delta, 2019 (Springer, 2017).

Focazio, M., Reilly, T., Rupert, M. & Helsel, D. Assessing groundwater vulnerability to contamination: providing scientifically defensible information for decision makers, US department of interior and US geological survey, reston, VA, US geological survey Circular, p. No. 1224, (2002).

Huan, H., Wang, J. & Teng, Y. Assessment and validation of groundwater vulnerability to nitrate based on a modified DRASTIC model: A case study in Jilin City of Northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 440, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.08.037 (2012).

Oke, S. & Fourie, F. Guidelines to groundwater vulnerability mapping for Sub-Saharan Africa., Groundwater for Sustainable Development, vol. 5, pp. 168–177. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2017.06.007.

Arefin, R. R. A. D. J. Megacity solid waste disposal suitability mapping in dhaka, bangladesh: an integrated approach using remote sensing, GIS and statistics. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 910 (2024).

Aller, L., Bennett, T., Lehr, J., Petty, R. & Hackett, G. DRASTIC: A standardized system for evaluating groundwater pollution potential using hydrogeologic settings: U.S. Environmental Prot. Agency Report, pp. (1987). 600/2–87/035, p 641 .

Napolitano, P. & Fabbri, A. Single-Parameter Sensitivity Analysis for Aquifer Vulnerability Assessment using DRASTIC and SINTACS. In: Kovar, K. and Nachtnebel, H.P., Eds., HydrolGis Application of Geographic Information Systems in Hydrology and Water Resources Management, IAHS Publication, vol. 235, pp. 559–566., (1996).

Nahin, K., Basak, R. & Alam, R. Groundwater vulnerability assessment with DRASTIC index method in the Salinity-Affected Southwest coastal region of bangladesh: A case study in Bagerhat sadar, Fakirhat and rampal. Earth Syst. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-019-00144-7 (2019).

F. SD, Fundamental concepts in aquifer vulnerability, pollution risk and protection strategy, in In: Waegeningh HG, van WV, editors Vulnerability of soil and groundwater to pollutants, The Hague, pp. Vol 38, p 69–86. (1987).

a., C. M. & M, D. M. SINTACS R5-Valutazione e cartografia automatica della vulnerabilità degli acquiferi all’inquinamento con il sistema parametrico. Pitagora Bologna, p. 226 ., p. 191. (2000).

Chachadi AG, L. F. J. Seawater intrusion vulnerability mapping of aquifers using the GALDIT method. COASTIN 4, 7–9 (2001).

B. J. S. I. S., E. A., T. S. C. & E. J. O. T. J. P. &. T. T. K. Ojeda olivares, A simple method to evaluate groundwater vulnerability in urbanizing agricultural regions. J. Environ. Manage. 261, 110164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110164 (2020).

Busico, M. M. & G. A. L. &. Denitrification in intrinsic and specific groundwater vulnerability assessment: A review. Appl. Sci. 11, 10657. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112210657 (2021).

J. K. J. J., S. I. C. C. L. G. & Ahmed, S. S. L. H. J. Groundwater vulnerability assessment of shallow aquifer in the South Texas sand sheet using a GIS-based DRASTIC model. Modeling Earth Syst. Environment, 8, 3, (2022).

M Bordbar, R. F. B. S. Global review of modification, optimization, and improvement models for aquifer vulnerability assessment in the era of climate change. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 9, 45–67. https://doi.org/101007/s40641-023-00192-2 (2024).

Arafa, N. et al. Evaluation of Groundwater Sensitivity to Pollution Using GIS-Based Modified DRASTIC-LU Model for Sustainable Development in the Nile Delta Region., Sustainability, vol. 14, p. 14699, (2022).

A. J. L. K., F. B. G. N. C. N. M. L. H. R. K. E. E. S. P. &. M. M. Rama, assessment of intrinsic aquifer vulnerability at continental scale through a critical application of the drastic framework: the case of South America. Sci. Total Environ. 823, 153748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153748 (2022).

Barbulescu, A. Assessing Groundwater Vulnerability: DRASTIC and DRASTIC-Like Methods: A Review., Water, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 1356. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/w12051356.

Chakraborty, B. et al. Groundwater vulnerability assessment using GISbased DRASTIC model in the upper catchment of Dwarakeshwar river basin, West bengal, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 81 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-10002-3 (2022). no. 2.

Kirlas, M., Karpouzos, D. & Georgiou, P. Application of Gis-Based modified Drastic for Groundwater Vulnerability Assessment in Nea Moudania Aquifer, Greece., in 12th International Hydrogeological Congress of Greece and Cyprus / Nicosia, (2022).

Merchant, J., Whittemore, D., Whistler, O., McElwee, C. & Woods, J. Groundwater Pollution Hazard Assessment: A GIS Approach., in In Proceedings of the International Geographic Information Systems (IGIS) Symposium, Association of American Geographers, Washington, DC, USA, 3, pp. 103–115., 15–18 November, (1987).

Hamza, W. The nile delta, in. In In: Dumont H.J. (eds) the Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use 75–94 (Springer, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9726-3_5.

A.-M. I. A., M. E. H. A. M. F. A. H. &. E.-s. S. M. Goher, Evaluation of surface water quality and heavy metal indices of Ismailia Canal, Nile River, Egypt, vol. 40, no. (3), 225–233, (2014).

Arnous, M., El-Rayes, A. & Green, D. Hydrosalinity and environmental land degradation assessment of the East nile Delta region, Egypt. J. Coastal. Conserv. 19, 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-015-0402-z (2015).

Abdel-Fattah, M. & Helmy, A. Assessment of water quality of wastewaters of Bahr El-Baqar, bilbies and El-Qalyubia drains in East delta, Egypt for irrigation purposes. Egypt. J. Soil. Sci. 55, 287–302 (2015).

Mabrouk, B. et al. A review of seawater intrusion in the nile Delta groundwater system – the basis for assessing impacts due to climate changes and water resources development. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Dis. 10 (8), 10873–10911. https://doi.org/10.5194/hessd-10-10873-2013 (2013).

Salem, Z., Fathy, M., Helal, A., Afifi, S. & Attiah, A. Groundwater quality for irrigation as an aspect of sustainable development approaches: A case study of Semi-Arid area around Ismailia canal, Eastern nile delta, egypt., in A. Negm and A. Elkhouly (eds.), Groundwater in Egypt’s Deserts, Springer Water, 295–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77622-0_12. (2021).

Alam, F., Umar, R., Ahmed, S. & Dar, F. A new model (DRASTIC-LU) for evaluating groundwater vulnerability in parts of central Ganga plain, India. Arab. J. Geosci. 7 (3), 927–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-012-0796-y (2012).

Maqsoom, A. et al. GIS based DRASTIC model and an adjusted DRASTIC model (DRASTICA) for groundwater susceptibility assessment along the China–Pakistan economic corridor (CPEC) route. Int. J. Geo-Inform. 9 (3), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9050332 (2020).

Fannakh, A. F. A. DRASTIC, GOD, and SI approaches for assessing groundwater vulnerability to pollution: a review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 34, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00646-8 (2022).

Mumtaz, M., Jahanzaib, S. H., Hussain, W., Khan, S., Youssef, Y. M., Qaysi, S., Abdelnabi, A., Alarifi, N., & Abd-Elmaboud, M. E., synergy of remote sensing and Geospatial technologies to advance sustainable development goals for future coastal urbanization and environmental challenges in a riverine megacity. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information. 14 (1), 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14010030

Negm, A., Sakr, S., Abd-Elaty, I. & Abd-Elhamid, H. An Overview of Groundwater Resources in Nile Delta Aquifer., in The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry, p. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/698_2017_193

Pennington, B., Sturt, F., Wilson, P., Rowland, J. & Brown, A. The fluvial evolution of the holocene nile Delta. Q. Sci. Rev. 170, 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.06.017 (2017).

Said, R. The Geological Evolution of the Nile Riverp 151 (Springer, 1981).

Zaghloul, Z., Essawy, M. & El-Sherbini Grain size and texture analysis of the subsurface sediments of Sidi Salim well 1. Nile delta, Egypt. Bull. Fac. Sci. 4, 79–98 (1977).

Domroes, T. A. Recent Temporal and Spatial temperature changes in Egypt. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 51–63 (2005).

Morsy, W. Environmental Management to Groundwater Resources for Nile Delta Region., Cairo: Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt, (2009).

APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (23rd ed.), (2017).

Hach Water Analysis Handbook. 2nd Edition, vol. 303, no. 669–3050, (1992).

ESRI & April ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 Help (Includes ArcMap, ArcCatalog, ArcGlobe, and ArcScene Softwares), Available online: (2020). https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/ (accessed on 1 2020.

Fergany, E. & Sylvette, B. Microtremor measurements in the nile Delta basin, egypt: response of the topmost sedimentary layer. Seismol. Res. Lett. 80, 591–598 (2009).

Gad, A. & Ali, R. Creation of GIS digital land resources database of the nile delta, egypt, for optimal soil management. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 19, 641–6500 (2011).

El-Fayoumi, I. Geology of the quaternary succession and its impact on the groundwater reservoir in the nile Delta region. Bull Fac. Sci. Mansoura University: Mansoura Egypt, (1987).

Mabrouk, M., Jonoski, A., Essink, G. & Uhlenbrook, S. Assessing the fresh-saline groundwater distribution in the Nile delta aquifer using a 3D variable-density groundwater flow model., Water, vol. 11, p. 1946. (2019).

Wei, A., Bi, P., Guo, J., Lu, S. & Li, D. Modified DRASTIC model for groundwater vulnerability to nitrate contamination in the Dagujia river basin, China. Water Supply. 21 (4), 1793–1805. https://doi.org/10.2166/ws.2021.018 (2021).

Patel, P., Mehta, D. & Sharma, N. A review on the application of the DRASTIC method in the assessment of groundwater vulnerability. Water Supply. 22 (5), 5190–5205. https://doi.org/10.2166/ws.2022.126 (2022).

Lodwick, W., Monson, W. & Svoboda, L. Attribute error and sensitivity analysis of map operations in geographical informations systems: suitability analysis. Int. J. Geographical Inform. Syst. 4 (4), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/02693799008941556 (1990).

Shahab, A. et al. Groundwater vulnerability assessment using GIS-based DRASTIC method in the irrigated and coastal region of Sindh province, Pakistan. Hydrol. Res. 50 (1), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.2018.001 (2019).

Moges, S. & Dinka, M. Assessment of groundwater vulnerability using the DRASTIC model: A case study of Quaternary catchment A21C, Limpopo River Basin, South Africa., Journal of Water and Land Development, vol. 49, no. IV– VI, pp. 35–46. (2021). https://doi.org/10.24425/jwld.2021.137094.

Shajedul, I. M. M. M. G. Development of an integrated irrigation water quality index (IIWQIndex) model. Water Supply. 22 (2), 2322–2337. https://doi.org/10.2166/ws.2021.378 (2022).

O. I., V. S. & Etuk, R. V. Vulnerability Mappingas a tool to foster groundwater protection in areas subject to rapid population expansion: the case study of Abuja federal capital territory (Nigeria). J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 42, 101158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2022.101158 (2022).

Stevenazzi, S., Masetti, M. & Beretta, G. Groundwater vulnerability assessment: from overlay methods to statistical methods in the Lombardy plain area. Acque Sotter -Ital J. Groundw. P 6, (2017).

Chitsazan, M., Akhtari, Y., Gis-Based, A. & Model of assessing aquifer vulnerability in Kherran plain, khuzestan, Iran. Water Resour. Manage. 23 (6), 1137–1155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-008-9319-8 (2009).

M. A., E. Comparison of DRASTIC and DC resistivity modeling for assessing aquifer vulnerability in the central nile delta, Egypt. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 350. 101007/s12665-017-6688-4 (2017).

El-Fakharany, M. & Mansour, N. Assessment of Water Resources Quality at the Southeastern Part of the Nile Delta, Egypt., in The International Conference on Water Conservation in Arid Regions, (2009).

Ismail, A. & Ryden, N. Engineering geological characteristics of soil materials, East nile delta, egypt. World academy of science, engineering and technology international journal of geological and environmental engineering. Int. Sch. Sci. Res. Innov. 6, 282–287 (2012).

Khan, M., Umar, R. & Lateh, H. Assessment of aquifer vulnerability in parts of Indo gangetic plain, India. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 5 (11), 1711–1720 (2010).

Zendehbad, M. M. M. M. C. P. L. W. M, Nitrate in groundwater and agricultural products: intake and risk assessment in northeastern Iran, vol. 29, no. 52:78603–78619, (2022).

Dizaji, A., Hosseini, S., Rezaverdinejad, V. & Sharafati, A. Groundwater contamination vulnerability assessment using DRASTIC method, GSA, and uncertainty analysis. Arabian Journal of, Geosciences, vol. 13, no. 14, pp. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-020-05650-x., .

Hasan, S., Salem, Z. & Sefelnasr, A. Assessment of Hydrogeochemical Characteristics and Seawater Intrusion in Coastal Aquifers by Integrating Statistical and Graphical Techniques: Quaternary Aquifer, West Nile Delta, Egypt., Water, vol. 15, p. 1803. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/w15101803.

Ayers, W. D. W. R. S. Water quality for agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Irrigation and drainage Paper 29 Rev., FAO, Rome, 195.

Sabatakakis, N. K. G. V. E. L. S. Landslide susceptibility zonation in Greece, Nat. Hazards., vol. 65, pp. 523–543. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-012-0381-4.

Youssef, Y.M., Gemail, K.S., Sugita, M. et al, Natural and Anthropogenic Coastal Environmental Hazards: An Integrated Remote Sensing, GIS, and Geophysical-based Approach., Surv Geophys, vol. 42, pp. 1109–1141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-021-09660-6.

Youssef, Y. M., AlMetwaly, W. M., Saber, M., Abdelshafy, M., Qaysi, S., Alarifi, N., & Wahba, M. Integrating Geospatial and Hydrodynamic Modelling to Unravel Cultural Heritage Vulnerability to Dam Breaches and Flash Flood in Arid Environments, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 30, p. 105605, (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2025.105605

Thabit, S. W. & F. E.-S. A. &. Role of silt and clay fractions in organic carbon and nitrogen stabilization in soils of some old fruit orchards in the nile floodplain, Sohag governorate, Egypt. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 23, 2525–2544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-023-01209-3 (2023).

Banton, V. J. O, Evaluation of groundwater vulnerability to pesticides: a comparison between the pesticide drastic index and the PRZM leaching quantities, 4, no. (3):285–296 (1989).

Metwally, M.I., Armanuos, A.M. & Zeidan, B.A. Comparative study for assessment of groundwater vulnerability to pollution using DRASTIC methods applied to central Nile Delta, Egypt. Int J Energ Water Res 7, 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42108-022-00198-w (2023).

Gad, M. & El-Hattab, M. Integration of water pollution indices and DRASTIC model for assessment of groundwater quality in El Fayoum depression, Western desert, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 158, 103554 (2019).

Ouedraogo, I. Defourny, P. & Vanclooster, M. Mapping the groundwater vulnerability for pollution at the pan African scale. Sci TotalEnviron. 544, 939–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.135 (2015).

Leaven, M.T. Hydrogeological study of the Nile Delta and adjacent desert areas, Egypt, with emphasis on hydrochemistry and isotope hydrology, M.Sc. thesis, Free University, Amsterdam. Also published by RIGW/IWACO as Technical Note TN 77.01300-91-01. (1991).

RIGW. Groundwater Resources and Projection of Groundwater development, Water security project (WSP). Research Institute for Groundwater, Egypt. (1992).

Bahr, R. Groundwater Management and Saltwater Intrusion in Nile Delta Aquifer, Berlin TU, Germany. (1995).

Sallouma, M.K. & Gomaa, M.A. Groundwater quality in the Miocene aquifers east and west of the Nile Delta and in the North Western Desert, Egypt. Ain Shams Sci. Bull. 35, pp. 47–72. (1997).

Sherif, M.M., Sefelnasr, A. & Javad, A. Incorporating the concept of equivalent freshwater 15 head in successive horizontal simulations of seawater intrusion in the Nile Delta aquifer, Egypt. J. Hydrol. Elsevier B.V (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the USGS Earthexplorer for providing the Landsat and SRTM datasets.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Authors confirm No external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Competing Interests and Funding: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salem, Z.E., Attiah, A.M., Negm, A. et al. Assessment of quaternary aquifer pollution sensitivity using modified DRASTIC models around stressed Canal in Eastern Nile delta, Egypt. Sci Rep 15, 25287 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09489-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09489-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Integrating fuzzy C-means clustering and shannon entropy with hydrogeochemistry for irrigation water suitability mapping in semi-arid hard-rock terrains

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)

-

Integrated geophysical healthy assessment for eco development and coastal sustainability in Ras Gamila, Egypt

Scientific Reports (2025)