Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is an important nosocomial pathogen responsible for a wide range of human infections. The emergence of multidrug resistance (MDR) causes life-threatening nosocomial infections. Also, the formation of biofilm helps it survive on abiotic surfaces and is transferred through healthcare workers, thereby causing nosocomial infections. Hence, we study the current antibiotic resistance patterns and virulence factors in our clinical and colonizing isolates. A total of 92 isolates (44 colonizing and 48 clinical) of A. baumannii were included in the study. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by VITEK 2. Biofilm formation was assessed by the tissue culture plate method. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for oxacillinases, MBLs and biofilm-associated genes were performed. Meropenem resistance was found in 42 (87.5%) of the clinical and 44 (97.7%) of the colonizing isolates. A strongly adherent biofilm was produced by 11 (22.91%) of the clinical and 12 (27.27%) of the colonizing isolates. Biofilm-associated genes, ompA, bap and csuE were present in 45 (93.7%), 47 (97.9%) and 44 (91.6%) of the clinical isolates, respectively and in all the colonizing isolates. blaOXA23-like was more prevalent in colonizing than clinical isolates. blaOXA-58-like and blaOXA-24-like were present in very few isolates. The presence of metallo beta-lactamase (MBLs) was observed to be lower than oxacillinases. NDM1 was present in 15.29%, SIM in 27%, GIM in 14.11%, VIM in 32.9%, SPM in 5.8%, and IMP in 1.2% of the meropenem-resistant isolates. Carbapenem resistance (XDR) is increasing in A.baumannii. Biofilm formation is an important virulence factor responsible for its survival in the hospital environment and causes nosocomial infections. Biofilm-producing isolates were also found to be carbapenem-resistant. Strict disinfection procedures are to be followed to prevent its spread in the hospital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is an aerobic gram-negative coccobacillus. It is a free-living saprophyte in soil and water and is frequently found as a commensal flora of man and animals. It belongs to the “ESKAPE” six pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, A.baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) which are known for their multidrug resistance and virulence. This group is responsible for most nosocomial infections and can escape the biocidal effect of antimicrobial agents1. A. baumannii accounts for ~ 2% of all healthcare-associated infections in the Western world, doubles in Asia and the Middle East2. The development of multidrug resistance among strains of Acinetobacter has caused a serious public health problem. This resistance to antibiotics by A. baumannii is mainly mediated by the production of β-lactamases, reduction in outer membrane permeability, efflux pump activation and changes in penicillin-binding proteins3. Multidrug resistance (MDR) is resistance to at least three classes of antimicrobials, i.e., Cephalosporins, Aminoglycosides and Fluoroquinolones. Extensive drug resistance (XDR) is MDR plus resistance to carbapenems. Pan drug resistance (PDR) consists of XDR plus resistance to Polymyxins4. More than 45% of the isolates are reported to be Carbapenem-resistant globally2. Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) has listed A. baumannii as a pathogen of critical importance for the discovery of novel antimicrobials5. A. baumannii can survive in a desiccated environment. Biofilm formation, adhesion to the abiotic surface, outer membrane protein, motility, oxidative stress mechanisms, drug efflux and serum resistance contribute to its virulence6. Biofilm-forming strains are more resistant than planktonic forms7. Biofilm helps it to survive on abiotic surfaces and disseminates through healthcare workers, thus making it an important nosocomial pathogen. Most of these nosocomial infections are MDR3. Genes most frequently associated with biofilm are bap, csuE, ompA, and blaPER-1. The bap gene is expressed on the surface of bacterial cells and is responsible for biofilm formation on both biotic and abiotic surfaces. 79.2% of clinical isolates have the bap gene7. This makes A. baumannii an important pathogen. Hence, we undertook to study the current scenario of antibiotic resistance patterns and virulence factors in our clinical and colonizing isolates.

Material and methods

This is a retrospective analytical study. A. baumannii isolates from clinical and surveillance samples, which were isolated between 2015 and 2020, were stored at − 80 °C in 16% glycerol broth and were kept in our repository. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the institutional Human Ethical Committee (Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute) waived the need to obtain informed consent. A total of 92 isolates (44 colonizers and 48 clinical isolates from patients) of A. baumannii from the repository were included in the study. Isolates from nasal swabs and throat swabs from patients were considered colonizers irrespective of the infection/colonization status of the patient. Isolates from nineteen patients were both clinical and colonizers. All the isolates were revived on 5% sheep blood agar and reconfirmed as A. baumannii by MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and the presence of a blaOXA-51-like gene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers and conditions8.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by VITEK AST N 281 cards. Sensitivity to colistin was evaluated using the micro broth dilution method as recommended by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines9. The results were interpreted as intermediate and resistant, as there is no sensitive breakpoint for colistin as per CLSI 2022. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) decided in 2020 to remove the “susceptible” breakpoint for colistin. This means that colistin is no longer classified as a drug with a clear threshold for determining whether bacteria are susceptible to it. Studies showed that colistin often fails to achieve effective bacterial killing at safe doses. The drug’s behaviour in the body varies widely, making it difficult to set a reliable breakpoint.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ≤ 2 µg/dl is considered intermediate, and > 2 µg/dl as resistant.

The biofilm formation was assessed using the tissue plate culture method10,11. Briefly, A. baumannii isolates were grown overnight in Luria–Bertani broth with 0.25% glucose (LBG) at 37ºC. Cultures were diluted 1:50 in freshly prepared LBG. Then, 200 µl of suspension was inoculated in wells of sterile flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Costar, 3370) in quadruplets, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 72 h. After three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the biofilm was stained with crystal violet 1%(w/v) for 25 min and again washed with PBS. The adherent cells were resolubilized with 200 µl of ethanol/acetone (80:20 V/V) and the contents were transferred to a separate 96-well plate. The optical density (OD) was measured using a spectrophotometer (Multiscan Sky, Thermo Fisher Scientific). As previously described, the results were interpreted as weak, moderate and strong. The adherence capabilities of the test strains were classified into four categories; three standard deviations (SDs) above the mean OD of the negative control (broth only) was considered as the cut-off optical density (ODc). Isolates were classified as follows: if OD ≤ ODc, the bacteria were non-adherent; if ODc < OD ≤ 2 × ODc, the bacteria were weakly adherent; if 2 × ODc < OD ≤ 4 × ODc, the bacteria were moderately adherent; if 4 × ODc < OD, the bacteria were strongly adherent11. A. baumannii ATCC 19606 strain was used as a positive control12.

PCR for Carbapenems like MBLs like; VIM, IMP, GIM, SPM, SIM13, NDM-114, oxacillinases like; blaOXA-51-like, blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like and blaOXA-58-like8 and biofilm-associated genes like; bap, csuE and ompA blaPER-115 were performed by previously published methods.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. The chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare categorical variables between two groups; a P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Adherence of biofilm was compared in carbapenem-resistant strains of clinical and colonizing isolates.

Results

More than 90 per cent of the isolates were resistant to meropenem, imipenem, doripenem, cefepime, ceftazidime, piperacillin/ tazobactam, ticarcillin/clavulanic acid and ciprofloxacin. Most of the isolates were susceptible to minocycline (74%) and tigecycline (80%) (Fig. 1). Colistin MIC by micro broth dilution showed 95.6% intermediate and 4.4% resistance among all the 92 isolates. 42 (87.5%) of the clinical and 43 (97.7%) of the colonizers were resistant to meropenem.

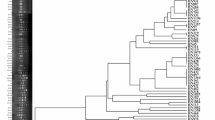

Colonizing isolates were found to be 100% resistant to cefepime, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, doripenem, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam and ticarcillin/clavulanate. Clinical isolates also showed around 87–91.7% resistance to these antibiotics. The extent of adherence in these two types of isolates was not statistically significant (Fig. 2). Similarly, meropenem-sensitive isolates showed no statistically significant difference in biofilm production. Also, when biofilm adherence was compared in resistant clinical isolates and colonizers, there was no statistically significant difference (p-value 0.488) (Fig. 2). And, when the strong biofilm producers were compared with meropenem-resistant isolates, no significant difference was found.

Biofilm-associated genes, ompA, bap and csuE, were present in all the colonizers and in more than 90% of the clinical isolates. However, per-1 was present in half of the clinical and colonizing isolates. VIM was the most prevalent MBL present in both clinical and surveillance isolates. 33 (39%) meropenem-resistant isolates had none of these genes. (Tables 1 and 2).

MBLs found in the present study were NDM1, SIM, VIM, GIM, SPM, and IMP. VIM was the most common in clinical isolates, and SIM and VIM were in the colonizing isolates. The MBLs were equally prevalent in both types of isolates and were not statistically significant Table 2.

Discussion

Nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant A.baumannii are rising. This is due to its ability to form biofilm and survive in the hospital environment. In the present study, 92 isolates of A. baumannii, both clinical and colonizing, were included to compare the biofilm formation and antimicrobial resistance patterns.

The presence of blaOXA51-like, a group D Carbapenemase gene, intrinsic to A. baumannii species, was found in all the isolates16. The rapid emergence of antimicrobial resistance among A. baumannii has become a serious public health problem. In a study, 96.96% of A. baumannii isolates from Romania were resistant to imipenem, meropenem and ciprofloxacin17. At the same time, an Indian study showed that resistance to meropenem, imipenem, and piperacillin-tazobactam is 98.4%18. However, the present study shows a high resistance rate to piperacillin-tazobactam (94%), cefepime (94%), meropenem (91%), imipenem (92%), ceftazidime (92%) and ciprofloxacin (95%), similar to both studies. In the present study, we also observed 87.2% of meropenem resistance in clinical isolates and 96.2% in colonizers. This similarity in both types of isolates could be because of the colonization of the patients with resistant isolates from the hospital environment, which are resistant. Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii are increasing in developing countries like India, Pakistan, Korea. Even colistin-resistant isolates are also emerging. The first reported colistin-resistant isolate is from Czech Republic in 199919. Meropenem is routinely given to the inpatients in our hospital. Hence, a high level of resistance is seen in our isolates. In India, Carbapenem resistance rates have exceeded 40%, the maximum being in Tamil Nadu, i.e., 67–74% as claimed by Alagesan20, and the predominant Carbapenemase in A. baumannii are OXA enzymes21. Most of the study isolates were from the ICU, hence, even higher resistance patterns were seen.

In the present study, the presence of blaOXA51-like in all the isolates, blaOXA23-like in 91%, blaOXA58-like in 15% and blaOXA24-like in 3% of the isolates was observed. No statistically significant difference was observed in clinical and colonizing isolates. A similar study showed blaOXA51-like to be present in all isolates, blaOXA23-like present in 81.4% of the isolates, and none of the isolates had blaOXA58-like and blaOXA24-like22. An Indian study conducted at PGIMER Chandigarh showed the presence of blaOXA-51-like, blaOXA-23-like and blaOXA58-like in 100%, 97.7% and 3.5%, respectively23. In the present study, all the resistant isolates were positive for blaOXA23-like. Among the 10 meropenem susceptible isolates, 1 was positive for blaOXA23-like, 3 for blaOXA-24-like, 2 for blaOXA58-like and 4 of them for neither of these three genes. This could be due to the non-expression of the genes or many of these genes may be silent and require IS before them to express resistance24 A study conducted in Iran observed a significant difference between clinical and environmental isolates for the presence of blaOXA23-like and biofilm formation was more in environmental isolates than in clinical isolates25. In this study, these oxacillinases were also found in colonizing isolates. This could be due to circulating endemic strains in the hospital due to earlier outbreaks. In the present study, a statistically significant correlation was observed among clinical and colonizing isolates for the presence of blaOXA23-like, however, no difference was observed in carbapenem-resistant and biofilm-forming isolates. A few studies have reported the co-existence of blaOXA23-like and blaNDM-1 in Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter isolates26. However, no statistically significant difference was observed in the present study, which could confirm this relationship. blaOXA23-like was present in all meropenem-resistant isolates, followed by MBLs. blaOXA-23-like enzyme confers the resistance mechanism to ticarcillin, meropenem, amoxicillin, and imipenem in vivo1. NDM1 is the most prevalent MBL to be observed in the present study. A recent study from Iran showed 13.3% of blaIMP-1 and 28.9% of blaVIM-1 genes in carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates. Also, the blaNDM gene was absent in all the isolates27. An Indian study showed the presence of VIM in 48.6% of the resistant isolates, NDM in 40.5% of the isolates, and IMP in none of the isolates23, contrary to the present study. Hence, MBLs also have a role in carbapenem resistance, however, blaOXA-23-like has a major role.

The ability to form biofilm is the most important virulence factor responsible for the pathogenicity of A. baumannii. Microbial biofilm formation on wounds makes the treatment difficult due to multidrug resistance among these strains28. In the present study, 85% of the isolates produced biofilm, of which 24% were strongly adherent. 85.4% of clinical and 86.5% of colonizing isolates were biofilm producers. A study showed that 90.6% of the isolates formed biofilm, of which 55.6% were strong biofilm producers. However, no statistically significant difference was established between MDR and non-MDR isolates in the case of biofilm production29. Zeighami et al. showed a significant correlation between strong biofilm producers and antibiotic resistance (XDR), where 58% of the isolates were strong biofilm producers30. Out of 85% of biofilm-forming isolates in the present study, 94.12% were Carbapenem-resistant. No statistically significant difference was observed when strongly adherent isolates were compared with meropenem-sensitive and resistant isolates (p value 0.75). We cannot consider this remarkable, as 90% of our isolates are Carbapenem-resistant, and most are also biofilm-producing. bap, csuE, ompA, and blaPER-1 are responsible for the biofilm formation. The frequency of these genes in the present study was 94% for ompA, 98% for bap, 94% for csuE and 51% for blaPER-1. A study demonstrated the presence of csuE in 91.3%, bap in 81.7% and ompA in 85.6% of the isolates. All the ompA-positive isolates were observed to be MDR31. The occurrence of these genes in another study comparing infection and colonizing isolates demonstrated that ompA and csuE in infection isolates were 95% and 85%, respectively. Among the colonizing isolates, the frequency of virulence genes was 94.44% for both ompA and csuE32. An Indian study on 307 clinical isolates of A. baumannii 71.07% of MDR isolates were biofilm producers. OmpA was produced by 31.92% of the isolates, blaOXA-23-like was predominant in 96% of the isolates, and blaOXA-58-like in 6% of the isolates33. Whereas, in the present study, increased frequency of bap, csuE, ompA, and blaPER-1 was seen in clinical as well as the colonizing isolates, and ompA, bap, and csuE were present in all the strongly adherent isolates. In another study, the incidence of blaPER–1, bap, ompA, and csuE genes amongst the isolates ranged from 46.7 to 90%34. At least one of these genes was observed in biofilm-producing isolates. No statistical difference was observed between these genes and the severity of biofilm adherence. In the present study, resistance patterns and biofilm production were not statistically different between the clinical and colonizing isolates. That could be because most patients had multiple hospital admissions due to chronic lung infections and were likely to be colonized by the more resistant and virulent strains in the hospital.

Conclusion

A. baumannii is an important nosocomial pathogen. This is being strong biofilm producer and multidrug resistant, and can survive in the hospital. This colonizes the nose, throat and hands of the healthcare workers, leading to transmission. Robust infection control practices are needed to prevent nosocomial infections and outbreaks in clinical settings.

Limitation of the study

It was a retrospective study where the isolates from our repository were used. Hence, clinical details of the patients, treatment history and outcome data were not available to us.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

References

Ibrahim, S., Al-Saryi, N., Al-Kadmy, I. M. S. & Aziz, S. N. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii as an emerging concern in hospitals. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48(10), 6987–6998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-021-06690-6 (2021).

Colquhoun, J. M. & Rather, P. N. Insights into mechanisms of biofilm formation in Acinetobacter baumannii and implications for uropathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00253 (2020).

Harding, C. M., Hennon, S. W. & Feldman, M. F. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16(2), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.148 (2018).

Ramirez, M. S., Bonomo, R. A. & Tolmasky, M. E. Carbapenemases: Transforming Acinetobacter baumannii into a yet more dangerous menace. Biomolecules 10(5), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10050720 (2020).

WHO. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (2020).

Khamari, B. et al. Molecular analyses of biofilm-producing clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a South Indian Tertiary Care Hospital. Med. Princ. Pract. 29(6), 580–587. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508461 (2020).

Yang, C. H., Su, P. W., Moi, S. H. & Chuang, L. Y. Biofilm formation in Acinetobacter baumannii: Genotype-phenotype correlation. Molecules 24(10), 1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24101849 (2019).

Mostachio, A. K., Van Der Heidjen, I., Rossi, F., Levin, A. S. & Costa, S. F. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding oxacillinases and metallo-β-lactamases in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. J. Med. Microbiol. 58(11), 1522–1524. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.011080-0 (2009).

CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 32nd ed. CLSI supplement M100 (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2022).

O’Toole, G. A. & Kolter, R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: A genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 28(3), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x (1998).

Azizi, O. et al. Molecular analysis and expression of bap Gene in biofilm-forming multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 5(1), 62–72 (2016).

Babapour, E., Haddadi, A., Mirnejad, R., Angaji, S. A. & Amirmozafari, N. Biofilm formation in clinical isolates of nosocomial Acinetobacter baumannii and its relationship with multidrug resistance. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 6(6), 528–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.04.006 (2016).

Ellington, M. J., Kistler, J., Livermore, D. M. & Woodford, N. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-beta-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59(2), 321–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkl481 (2007).

Zarfel, G. et al. Emergence of New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase, Austria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17(1), 129–130. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1701.101331 (2011).

Dallenne, C., da Costa, A., Decré, D., Favier, C. & Arlet, G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65(3), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkp498 (2010).

Turton, J. F. et al. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii by detection of the bla OXA-51-like carbapenemase gene intrinsic to this species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44(8), 2974–2976. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01021-06 (2006).

Gheorghe, I. et al. Subtypes, resistance and virulence platforms in extended-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Romanian isolates. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 13288. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92590-5 (2021).

Sannathimmappa, M. B., Nambiar, V., Aravindakshan, R. & Al-Kasaby, N. M. Profile and antibiotic-resistance pattern of bacteria isolated from endotracheal secretions of mechanically ventilated patients at a tertiary care hospital. J. Educ. Health Promot. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1517_20 (2021).

Roy, S., Chowdhury, G., Mukhopadhyay, A. K., Dutta, S. & Basu, S. Convergence of biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Front. Med. 24(9), 793615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.793615 (2022).

Alagesan, M. et al. A decade of change in susceptibility patterns of Gram-negative blood culture isolates: A single center study. Germs 5(3), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.11599/germs.2015.1073 (2015).

Kazi, M., Nikam, C., Shetty, A. & Rodrigues, C. Dual-tubed multiplex-PCR for molecular characterization of carbapenemases isolated among Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas spp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 118(5), 1096–1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12770 (2015).

Al-Shamiri, M. M. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Acinetobacter baumannii enrolled in the relationship among antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation and motility. Microb. Pathog. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104922 (2021).

Kumar, S. et al. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates reveals the emergence of blaOXA-23 and blaNDM-1 encoding international clones in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 75, 103986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2019.103986 (2019).

Xu, L. et al. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains harboring inactive extended-spectrum beta-lactamase antibiotic-resistance genes. Chin. Med. J. 127(17), 3051–3057 (2014).

Bardbari, A. M. et al. Correlation between ability of biofilm formation with their responsible genes and MDR patterns in clinical and environmental Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. Microb. Pathog. 108, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.04.039 (2017).

Karthikeyan, K., Thirunarayan, M. A. & Krishnan, P. Coexistence of blaOXA-23 with blaNDM-1 and armA in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65(10), 2253–2254. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkq273 (2010).

Namaei, M. H. et al. High prevalence of multidrug-resistant non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli harboring bla and bla metallo-beta-lactamase genes in IMP-1 VIM-1 Birjand, South-East Iran. Iran. J. Microbiol. 13(4), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijm.v13i4.6971 (2021).

Thompson, M. G. et al. Validation of a novel murine wound model of Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58(3), 1332–1342. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01944-13 (2014).

Donadu, M. G. et al. Relationship between the biofilm-forming capacity and antimicrobial resistance in clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates: Results from a laboratory-based in vitro study. Microorganisms 9(11), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9112384 (2021).

Zeighami, H., Valadkhani, F., Shapouri, R., Samadi, E. & Haghi, F. Virulence characteristics of multidrug-resistant biofilm forming Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from intensive care unit patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 19(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4272-0 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of biofilm formation in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect. Drug Resist. 14, 2613–2624. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S310081 (2021).

Silva, A. M. et al. Investigation of the association of virulence genes and biofilm production with infection and bacterial colonization processes in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202120210245 (2021).

Gautam, D. et al. Acinetobacter baumannii in suspected bacterial infections: Association between multidrug resistance, virulence genes, & biofilm production. Indian J. Med. Res. 158(4), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.ijmr_3470_21 (2023).

Sherif, M. M., Elkhatib, W. F., Khalaf, W. S., Elleboudy, N. S. & Abdelaziz, N. A. Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii biofilms: Evaluation of phenotypic-genotypic association and susceptibility to cinnamic and gallic acids. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.716627 (2021).

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. conceptualized the research and wrote the manuscript; J.C. performed the experiments, tabulated the results, and wrote the original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional Human Ethical Committee (Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute) approved the project (code no VPCI/DIR/HIEC/2020/1849). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the committee waived the need to obtain informed consent. All experiments were performed according to relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choudhary, J., Shariff, M. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant biofilm forming Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from clinical and surveillance samples. Sci Rep 15, 33892 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09530-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09530-w