Abstract

National independent innovation demonstration zones (NIIDZs) play a crucial role in scientific and technological innovation (STI). However, there have long been disputes regarding their ability to continuously increase urban STI efficiency, the paths through which they generate innovation-driven effects, and their spatial effects. This study uses the panel data of 274 cities in China from 2006 to 2020 and applies various methods including the multiperiod difference-in-differences model, quantile model, and spatial Durbin model to systematically explore the impact of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency. The research findings are as follows: the positive impact of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency begins to emerge in the fourth year after their establishment and persists. The spatial effect is distance dependent, suppressing the STI efficiency of surrounding cities within 110 kms while promoting that of areas at a distance between 110 and 410 kms, with the strongest effect occurring at 360 kms. The mechanism analysis shows that NIIDZs affect urban STI efficiency through factor agglomeration, innovation environment optimization, and industrial structure transformation and upgrading. This study provides important policy insights for fully harnessing the innovation-driven effect of NIIDZs to increase urban STI efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to international experience, as economic development moves from the upper-middle-income stage to the high-income stage, the driving force of growth shifts from being factor dependent to being innovation driven1,2. The Chinese government recognizes the importance of scientific and technological innovation (STI) in economic development, emphasizing that innovation is the new driving force for economic growth and a key factor in catching up with advanced industrial economies; additionally, it has introduced a series of innovation-driven development policies3. After several years of development, China has made great strides in STI research. Figure 1 shows the STI in China from 2006 to 2021. At present, China has entered a stage of high-quality development, and "innovation as the first driving force" is the primary feature of this stage. At its twentieth national congress, the Communist Party of China (CPC) placed innovation-driven development at the core of the country’s modernization process, proposing that the power of science and technology be further harnessed to fuel development and that the overall effectiveness of the national innovation system be upgraded, thus reflecting the importance that the Chinese government attaches to STI development. Cities are essential nodes and key carriers of China’s innovation system, and improving urban STI efficiency constitutes a breakthrough for China in terms of shaping its innovation system and cultivating new dynamics and new advantages in economic development. Therefore, improving urban STI efficiency at the policy level has become a concern.

National independent innovation demonstration zones (NIIDZs) are built on the foundation of national high-tech zones (NHTZs) and represent a crucial measure of China’s innovation-driven strategy. Serving as a growth pole for regional development and a high ground for the agglomeration of innovation factors, NIIDZs provide the impetus, support, and guarantees for the technological innovation, industrial agglomeration, and capital investment required for regional innovation and development. They are key platforms for leading and radiating the independent innovation activities of the cities where they are located and are important spatial carriers for China to channel its scientific and technological strength to promote high-quality economic development. In 2009, based on the construction of the Zhongguancun high-tech zone, China approved the establishment of the first NIIDZ, the Zhongguancun NIIDZ4. As of November 2023, China had built 23 NIIDZs.

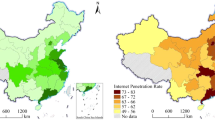

In terms of spatial layout, the approved NIIDZs include 10 eastern NIIDZs, such as the Shandong Peninsula, Southern Jiangsu, Hangzhou, and Fuzhou—Xiamen—Quanzhou; 5 central NIIDZs, such as Donghu, Zhengzhou—Luoyang—Xinxiang, and Changsha—Zhuzhou—Xiangtan; 5 western NIIDZs, including Chengdu, Lanzhou—Baiyin, and Urumqi—Changji—Shihezi; and 3 northeastern NIIDZs of Shenyang—Dalian, Changchun, and Harbin—Daqing—Qiqihar. Their spatial scope largely overlaps with China’s "Four Major Regions"5.

In 2020, the NHTZs involved in the 21 approved NIIDZs achieved a total output value of 9.6 trillion yuan, accounting for 9.5% of China’s GDP. The total profit reached 2.4 trillion yuan, which is 1.84 times greater than that in 2015, with an average annual growth rate of 13%. The internal R&D expenditure of enterprises in these zones reached 703.756 billion yuan, and the internal R&D expenditure of enterprises accounted for 7.3% of the STI park GDP, 3.3 times the national average. The number of authorized invention patents of enterprises in the zones was 163,000, and the number of invention patents per 10,000 employees was close to that of the regions with the highest global patent output. There are 81,636 high-tech enterprises in NIIDZs, accounting for 29.7% of the high-tech enterprises in NHTZs across the country; 546 national-level science and technology business incubators, accounting for 42% of the national total; and 900 national-level maker spaces, accounting for 39% of the national total. Accordingly, NIIDZs have become an important driving force for China to promote innovation and entrepreneurship, build a modern economic system, and achieve high-quality economic development. The establishment of NIIDZs is characterized by a strong emphasis on regional coordinated development. They have developed in a pattern of sequential advancement from east to west and from north to south, with multiple “radiating” points. This developmental pattern has formed a regional innovation layout on the Chinese map that features complementary advantages and coordinated interactions.

Cities serve as the spatial carriers of innovation activities. Improving the urban innovation level plays a crucial supporting role in the construction of an innovation-oriented country6. To explore the path of urban innovation and development with Chinese characteristics and improve the urban innovation level, China has made many attempts to formulate urban innovation policies7,8. As early as 2008, China launched a pilot program for innovative cities and has continuously expanded its scope. By the end of 2024, the number of national innovative city pilots had increased to 78. The construction of NIIDZs started later than that of innovative cities did, and there are many differences between the two in terms of their pilot policies.

In terms of policy objectives, NIIDZs aim to promote independent innovation, develop high-tech industries, lead economic transformation, and improve the innovation system. In contrast, the innovative city pilot policy focuses on enhancing the urban innovation level, promoting green development, and upgrading the industrial structure. With respect to the implementation scope, NIIDZs consist of specific regions approved by the State Council, with a relatively small number and uneven distribution. The innovative city pilot, however, involves numerous cities and has a wider scope. In terms of policy measures, the NIIDZ policies cover multiple fields, such as finance and taxation, science and technology, finance, and talent, which are systematic and comprehensive. The innovative city pilot policy focuses on enhancing the innovation level and achieving its goals by optimizing the innovation environment, promoting green technology innovation, and upgrading the industrial structure. It is more focused on the direct influencing factors of urban innovation.

Through an analysis of the construction of NIIDZs and a comparison of the relative positioning of NIIDZ construction policy and other national-level innovation policies, it is evident that the Chinese government has high expectations for the construction of NIIDZs. Given China’s unique governance structure, can this experimentally based governance model be translated into actual governance effectiveness? What is the mechanism by which NIIDZs drive improvements in urban STI efficiency? Does the impact of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency have spatial spillover effects? Unfortunately, existing studies have not provided clear answers to the above questions.

Therefore, the main accomplishments of this study are as follows:

-

①

By considering the NIIDZ policy as a quasinatural experiment, based on the panel data of 274 cities in China from 2006 to 2020, the asymptotic difference-in-differences method is used to systematically evaluate the magnitude and sustainability of the driving effect of NIIDZ policy on urban STI efficiency.

-

②

With respect to the factor concentration effect, innovation environment optimization effect, and industrial structure transformation and upgrading effect, the internal mechanism by which NIIDZ policy affects urban STI efficiency is comprehensively revealed.

-

③

The differences in the driving effect of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency under different dimensions are tested, and the spatial scope of the spatial spillover effect of NIIDZs is evaluated.

The main contributions of this study are as follows. First, it helps to evaluate existing public policies more scientifically and promotes public policies to achieve the mission of policy science advocated by Lasswell to improve human well-being9. Second, it tests whether a country with a unique governance structure such as China can transform institutional advantages into governance effectiveness through policy experiments, enriches research on the impact of government policies on urban STI activities, and provides a theoretical basis for understanding the internal driving force of urban innovation. Third, from the perspective of spatial effects, it estimates the spatial spillover effects of NIIDZs, fills the gap in research on the spatial effects of NIIDZs, and helps us consider how to optimize the policy layout from a spatial perspective and highlight the spatial radiation effects of policies.

Literature review and policy context

Literature review

Government policies and innovation activities

At present, the world situation is complex and changeable. STI has become an important means for countries to overcome development bottlenecks and strengthen their advantages in development10,11.Consequently, issues such as the impact of government behaviour on STI activities and the effectiveness of government innovation policies have triggered extensive discussions in academic, policy-making, and grassroots practice circles12,13,14, and a series of constructive achievements have been made15,16. Some studies have found that the appropriate participation of the government in STI activities can, to a certain extent, rectify the shortcomings of the market mechanism, guide the innovation behaviours of cities and enterprises, and allocate innovation resources more effectively17,18. In addition, government financial subsidies can ease the financing constraints faced by enterprises in their development, promote enterprise capital deepening, guide enterprise innovation behaviours, and improve innovation efficiency19,20. However, other studies have shown that government participation does not significantly promote innovation activities21,22. Sometimes, it may even have a negative impact, resulting in a loss of innovation efficiency23,24. The innovation behaviours of enterprises under government subsidies may merely be strategic. Therefore, government subsidies result in more of an expansion of the enterprise innovation scale rather than an improvement in innovation efficiency25. Some research based on principal–agent theory, crowding–out theory, information asymmetry theory, and other theories26,27shows that government subsidies suppress enterprise innovation incentives, crowd out enterprise R&D expenditures, and inhibit improvements in enterprise, industry, or city innovation levels28. There are still obvious differences in existing research on issues such as whether the government should participate in innovation activities and the effectiveness of government innovation policies.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of the NIIDZ policy

Following the implementation of the NIIDZ pilot policy, the issue of appraising its impacts has attracted the attention of many scholars29,30,31. Lan et al. (2022) found that the NIIDZ policy increases innovation in cities and that such policies are more effective in cities with poorer economic development and at increasingly lower levels32. Aisaiti et al. (2022) found that NIIDZs significantly increase the innovation capacity of their host cities by facilitating the flow of knowledge and the sharing of innovations and that this effect is more pronounced in cities with better public services and marketization and higher levels of digitization33. Liu et al. (2022) provided new empirical evidence on the policy effects of NIIDZs in terms of urban haze pollution governance34. They found that NIIDZ policies significantly contribute to the governance of urban haze pollution, with the promotion of high-tech firm clustering and the enhancement of a city’s innovation capacity playing a positive role. Yu et al. (2023) found that NIIDZs effectively enhance a city’s green total factor productivity and that talent pooling and local fiscal science and technology expenditures are essential paths through which NIIDZ policy promotes the city’s green total factor productivity35. Several scholars have empirically analysed the impact of NIIDZs on micro innovation subjects. Wei et al. (2023) selected 911 firms within the Shanghai Zhangjiang NIIDZ and 861 firms outside the park, applied the zero-inflated negative binomial model to analyse the difference in innovation performance between firms inside and outside the park and found that firms in the park presented significantly higher levels of innovation performance than did firms outside the park36. Unfortunately, this study did not conduct a more in-depth exploration of the mechanism through which the NIIDZ influences the innovation performance of firms in parks.

A review of the literature indicates that the current research on the effects of NIIDZ policies is still limited. First, although some studies have explored the effects of NIIDZ policies, few articles have examined the impact of NIIDZ policies on urban STI efficiency, which is not commensurate with the objective requirements of the in-depth advancement of China’s innovation-driven strategy at the present time. Second, there is still a lack of research on the main factors and mechanisms that should be considered in analysing the impact of NIIDZ policies on urban STI efficiency, which results in the limited scientific evidence provided by existing studies with respect to guiding the government to formulate and improve relevant policies. Therefore, a systematic assessment of the role of NIIDZs in promoting urban STI efficiency and its internal mechanism is the main goal of this study.

Research hypotheses

Existing theoretical studies and empirical analysis results indicate that the implementation effects of location-oriented policies exhibit strong heterogeneity37,38. Moreover, the implementation effects of location-oriented policies are influenced by a series of external environmental factors, such as residents’ preferences for their commuting and living patterns. The theoretical analysis by Busso et al. (2013) shows that if residents have completely identical preferences, location-oriented policies will lead to substantial net losses in social welfare39. The research findings of Austin et al. (2018), on the other hand, reveal that during the implementation of location-oriented policies, the subsidies provided by the government are capitalized into land rent, thus causing an increase in land rent or housing prices40. In this case, the greatest beneficiaries are not low-income groups but land or housing owners within the target area. Additionally, factors such as geographical location and city size affect the implementation effects of location-oriented policies41,42. For NIIDZ policy, the heterogeneity of its driving effect on improvements in urban STI efficiency is manifested mainly in the construction mode, city size, STI efficiency, and time dimensions.

In terms of the construction mode, there are significant differences in the methods of resource integration and allocation among different construction modes. By virtue of the resource integration advantages of multiple cities, NIIDZs that rely on urban agglomerations can achieve efficient cross-regional flow and the sharing of innovative elements. Each city can carry out a division of labour and cooperation based on its own industrial characteristics to form a complete innovative industrial chain. However, it may also encounter obstacles in the integration of cross-regional innovative resources and policy coordination, resulting in the weakening of policy effects. For NIIDZs that rely on a single city, the formulation and implementation of policies are relatively flexible. However, the radiation scope is limited, and the policy effects are more confined to local areas, with a weak driving effect on the surrounding regions, making it difficult to form a pattern of regional collaborative innovation and development. Such differences lead to variations in the agglomeration efficiency of innovative elements and the degree of refinement of the innovation ecosystem, which in turn affects the role of policies in enhancing urban STI efficiency.

In terms of the city size dimension, large cities possess innate advantages in terms of innovative resources due to their abundant talent reserves, substantial financial strength, and dense scientific research institutions. After the NIIDZ policy is implemented, an NIIDZ can rapidly form innovative clusters with deep integration of industry, academia, and research, generating significant scale effects and synergistic effects. From another perspective, the gaps in human capital and innovative resources in large cities are relatively small or even saturated. Therefore, the establishment of an NIIDZ may have an insignificant marginal effect on this type of city. In contrast, small and medium-sized cities are at a disadvantage in terms of both the quantity and quality of innovative resources. Moreover, their weak industrial support capabilities make it difficult to support the large-scale industrial application of STI achievements, resulting in a limited increase in the urban STI efficiency brought about by the policy.

In terms of the dimension of STI efficiency, when the STI efficiency of a city itself is low, it often indicates significant gaps in aspects such as the accumulation of innovative resources and the construction of the innovation system. At this time, the NIIDZ policy functions similarly to a “cardiotonic”, which can quickly fill these shortfalls by introducing external innovative resources, optimizing the innovation environment, and improving the innovation service system.

As the STI efficiency of a city gradually improves, the city achieves a certain scale of innovative resources and forms a relatively complete innovation system. On the one hand, the path dependence of the original innovation system restricts the implementation effect of new policies, making it difficult for the innovative elements promoted by the policies to quickly integrate into the existing system and play their roles. On the other hand, when the STI of the city reaches a relatively high level, further improvement becomes more difficult, and the marginal return created by the policy investment decreases, resulting in a gradual weakening of the driving effect of NIIDZs on STI efficiency.

In terms of the time dimension, the driving effect of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency shows strong heterogeneity at different time points after their establishment. According to the existing empirical evidence, the policy effects of the same location-oriented policy vary greatly at different time points. For example, in their study of the French enterprise free zone policy, Mayer et al. (2012), found that the impact of this policy on employment was significant only in the short term43. NIIDZ policies aim to improve STI efficiency through innovative reforms of institutional mechanisms such as encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship, equity incentives, and the integrated development of the science and technology finance industry. However, since the formulation and implementation of STI policies is a relatively systematic process, the policy effects become evident only when the policies are comprehensively and deeply implemented. Therefore, there may be a certain time lag in the effects of NIIDZ policies. As the reform of the institutional mechanisms underlying STI continues to deepen, NIIDZ policy effects may exhibit more obvious characteristics of heterogeneity.

Hypothesis 1

In the process of NIIDZ policies taking effect, due to differences in resource endowments and other factors among various regions, the policy effects of the innovative city pilot program are heterogeneous in terms of the construction mode, city size, STI efficiency, and time dimension. Theoretically, the intrinsic mechanism through which NIIDZs affect urban STI efficiency is reflected in the following three main aspects.

Factor agglomeration effects. According to signalling theory44, as crucial carriers of China’s STI activities, NIIDZs convey effective information on their strategic goals and development priorities to potential investors in the initial stage of construction, thereby spurring the aggregation of venture investors, high-tech enterprises, and STI talent. On the one hand, high-tech enterprises and their closely related supporting enterprises form multiple industrial chains and supply chains. These chains not only reduce transportation costs and shorten the transportation time but also enable downstream enterprises in the industrial chain to be the first to receive and transform the STI achievements of upstream enterprises, thus generating innovation outputs. On the other hand, downstream enterprises in the same city that have not settled in the NIIDZ are also more likely to receive and transform the innovation achievements of enterprises within the NIIDZ because of the agglomeration effect of NIIDZs. These enterprises can improve their own STI efficiency and further promote the improvement of the overall STI efficiency of the city. Innovation environment optimization effect. The effect of innovation environment optimization is remarkable. First, NIIDZs and local governments have introduced policies to support infrastructure construction, promote the construction of new infrastructure in cities and parks, focus on technological and application requirements, and drive the innovative development of information technologies such as the internet, big data, cloud computing, blockchain, and artificial intelligence. These policies therefore promote the in-depth integration of these technologies with enterprise demands, creating a “new engine” for STI.

Second, the establishment of NIIDZs has increased the attention of local city governments to innovation activities and advanced improvements in the intellectual property protection system. For example, Shenzhen in China took the lead in establishing a comprehensive intellectual property protection system with judicial protection as the mainstay, administrative protection as a support, and industry self-discipline, social supervision, arbitration, and mediation as supplements. This system effectively safeguards STI activities. Third, creating a market-oriented and law-based business environment is a key aspect of NIIDZ construction. Improving the level of marketization can foster a fair and vibrant competitive environment, protect the spirit of entrepreneurship, and stimulate the enthusiasm of innovation entities45. During this process, local governments pay more attention to constructing a market-centred resource allocation mechanism. This focus not only promotes the flow of innovation factors but also attracts high-quality innovation factors to agglomerate around NIIDZs, further enhancing the STI efficiency of cities.

Industrial structure transformation and the upgrading effect. First, NIIDZs are supported by high-tech industries. NIIDZs constantly transform traditional industries and spawn new industries while promoting the development and expansion of high-tech industries, which can drive the evolution of local industries from primary to secondary and tertiary industries at the aggregate level and is conducive to increasing the " quality " of the industrial structure46. Second, at the beginning of its establishment, an NIIDZ clearly defines the target industries that are the focus, which provides a clear guide for the subsequent development of the park in terms of industry selection. This approach largely circumvents the blind investment and overproduction behaviour of industries in the development process, reduces the friction resulting from irrational changes in the industrial structure, and lowers the cost of replacing factors. Finally, the externality of technological innovation diffusion within the NIIDZ strengthens the spatial association between parks and neighbouring cities, accelerates the diffusion and allocation of factors within the spatial scope, and synergistically transforms and upgrades the industrial structure, thus improving urban STI efficiency. Based on the above theoretical analysis, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2

The establishment of an NIIDZ enhances STI efficiency in the host city through the three paths of innovation factor agglomeration, innovation environment optimization, and industrial structure transformation and upgrading.

NIIDZs have been making continuous efforts to optimize the institutional environment and strengthen infrastructure construction by building a sound innovation ecosystem, which effectively reduces the enterprise transaction costs. On the other hand, leveraging informatization and networking construction within a city improves the efficiency of resource allocation, enabling flexible scheduling and efficient integration of production factors such as scientific and technological resources and high-tech labour forces among cities. Therefore, NIIDZs can not only enhance the innovation capabilities of pilot cities but also promote the two-way flow of innovative elements across regions through the spillover effect of policy dividends. Nonpilot cities can take advantage of the policy strengths of NIIDZ cities to obtain advanced technologies, innovative concepts, and high-level talents, effectively achieving the cross-regional sharing of innovative resources. This flow and sharing of resources have a significant spatial spillover effect on neighbouring regions, effectively enhancing the innovation vitality and competitiveness of surrounding cities and driving the coordinated development of regional innovation.

The driving effect of NIIDZs urban STI efficiency exhibits heterogeneous characteristics as the distance from NIIDZs increases. First, the flow and orderly allocation of innovative elements lead to the agglomeration of elements and the transformation and upgrading of the industrial structure. Owing to the existence of agglomeration externalities, cities where NIIDZs are located experience the most positive agglomeration externalities. However, the spillover effect of NIIDZs on improving neighbouring efficiency is rather complex. According to relevant theories in spatial economics47, an NIIDZ has a strong “siphon effect” on surrounding cities, thus forming a “shadow zone” around the central area48, which leads to the loss of innovative elements in the areas surrounding the NIIDZ. As a result, improving the level of STI efficiency is difficult. Only after the agglomeration shadow zone is eliminated can the NIIDZ generate a positive spillover effect on surrounding cities. When the spatial distance exceeds a certain extent, the driving effect of the NIIDZ on improvements in STI efficiency will decrease again for reasons such as the increased cost of knowledge transfer, which results in decreased transfer efficiency, the local preference characteristics of collaborative innovation, and the widespread existence of “local protectionism”. Therefore, there may be obvious spatial heterogeneity in the effect of an NIIDZ on improving the STI efficiency of surrounding cities. On this basis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3

The innovative city pilot policy not only promotes the urban innovation ability of the local region but also has a spatial spillover effect on neighbouring regions.

Hypothesis 4

There is significant spatial heterogeneity in the spatial spillover effect of an NIIDZ on the STI efficiency of neighbouring regions.

Research design

Sample selection and variable setting

Sample selection

The sample time span for this study is 2006–2020. The establishment of NIIDZs began in 2009, with the Wu Changshi NIIDZ in November 2018, Poyang Lake NIIDZ in 2019, and Changchun NIIDZ and Hadazi NIIDZ in 2022. These four NIIDZs were constructed in a relatively short period, and the impact of the STI on the efficiency of the cities in which they are located is not yet obvious; therefore, a sample of cities in which NIIDZs were newly established after September 2018 was excluded. Since NIIDZs were established on the basis of the construction of NHTZs and are upgraded versions of these high-tech zones, the choice of cities in which to build NIIDZs is not random; rather, these zones must be chosen among all of the cities that have already constructed NHTZs. Other cities that have not constructed NHTZs cannot be approved for the construction of NIIDZs. Therefore, we use 130 cities that have established NHTZs (By the end of 2020, China had approved the construction of 169 NHTZs. However, because the construction of NHTZs is characterized by "one city, many zones", that is, a city may have one or more NHTZs, the 169 NHTZs do not correspond to 169 cities). As the basic research sample, 60 cities that have established NIIDZs among the 130 cities as the experimental group (Some sample cities were deleted, the specific processing is as follows. Based on the China Torch Yearbook (2021), among the 169 NHTZs by the end of 2020: the Yanjiao High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Langfang City; the Jiangyin High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Wuxi City; the Wujin High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Changzhou City; the Kunshan High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Suzhou City; the Xiaoshan Linjiang High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Hangzhou City; the Yucheng High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Dezhou City; the Laiwu High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Jinan City; the Yellow River Delta High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Dongying City; the Yuancheng High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Heyuan City; the Guanghan High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Deyang City; and the Yangling High-tech Zone is treated as belonging to Xianyang City. County-level cities such as Yanji, Changshu, and Chuxiong, as well as counties and districts under Chongqing’s jurisdiction like Bishan, Rongchang, and Yongzhou, are removed. Moreover, due to a large amount of missing data, Shihezi, Changji, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, and Xiantao City are excluded from the sample) , and 70 cities that have not established NIIDZs as the control group. Then, we utilize the double difference method to examine the effect of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency.

Variable settings

-

Explanatory variable: Efficiency in urban STI (innoe). This study measures urban STI efficiency from the input‒output perspective using the DEA method. Considering that the radial DEA model has issues such as not covering slack variables in the measurement of inefficiency and not accounting for undesirable outputs, a nonradial, nonlinear piecewise SBM model49 based on slack variables and undesirable outputs is adopted because it can effectively address the slack problem of input variables.

Regarding the selection of measurement indices, among the input indicators, the research and development (R&D) capital stock is selected as the capital input. As for the labor input, it is represented by the number of urban scientific researchers, which is calculated as the sum of the employees in the fields of information transmission, software, and information technology services, and those in scientific research and technical services50. For output indicators, the number of patent applications accepted is used to measure the output quantity of innovation activities, and the number of authorized invention patents is selected to represent the output quality51. The reason is that invention patents have a high density of new knowledge and can better reflect the quality of innovation achievements52.

-

Core explanatory variable: the NIIDZ policy. The NIIDZ policy, the core explanatory variable in this study, is represented by the interaction term of the city-type dummy variable and the policy implementation time dummy variable (did = treat × post). Here, treat = 1 denotes cities with NIIDZs, and treat = 0 otherwise; post = 1 represents years after the establishment of NIIDZs, and post = 0 otherwise.

With respect to the establishment year of NIIDZs, some NIIDZs are established at the end of the year, with a short construction period in that year and a negligible impact on the STI efficiency of the host cities. Therefore, based on the approval dates from the State Council, if an NIIDZ is established before August 31st, it is regarded as established in the approval year. If it is established on September 1st or later, the following year is designated as its establishment year.

-

Control Variables: Inspired by previous studies53, this research defines control variables across several key dimensions, namely economic development, external openness, financial advancement, and industrial configuration. The economic development level (pgdp) is gauged through the natural logarithm of each region’s real per capita regional GDP. External openness (open) is quantified by the ratio of the RMB—converted import and export trade volume to the GDP. The financial development level (finance) is determined by the proportion of the RMB deposit balance in financial institutions to the GDP. The industrial structure (indust_stru) is measured as the ratio of the added value of the tertiary industry to the GDP. Urban entrepreneurial vitality (activation) is reflected by the proportion of private business owners and self—employed individuals in the total urban population at the end of the year. Population density (den) is computed as the quotient of the total population within the jurisdiction at year—end and the total area of the jurisdiction. Science and education resources (edu) are represented by the number of regular higher education institutions in the city. The degree of infrastructure construction (highways) is evaluated based on the per capita highway freight volume within the city.

Model building

The establishment of an NIIDZ can be considered a “quasinatural experiment”. The double-difference method is more suitable for this study because it effectively eliminates the influence of random factors on the results. Since each NIIDZ was established in stages, we choose the multiperiod double-difference method for the empirical analysis.

where c (= 1, 2,…, 130) denotes the city, t (= 2006, 2007,…, 2020) is the year, innoe is the explanatory variable used to measure the STI efficiency of city c in year t, did is the double difference estimator, control is the set of control variables, \({\lambda }_{c}\) is the city fixed effect, \({\mu }_{t}\) is the year fixed effect, and \({\varepsilon }_{ct}\) is the randomized disturbance term. In Eq. (1), the estimated coefficient \({\beta }_{1}\) estimates the average difference between a city’s STI efficiency before and after the NIIDZ policy shock. If \({\beta }_{1}\) is significantly positive, then the NIIDZ has an upgrading effect on the city’s STI efficiency.

Data description

Data for input and output variables are retrieved from multiple sources. These include the China Urban Statistical Yearbook, provincial and municipal statistical yearbooks, provincial and municipal science and technology statistical yearbooks, as well as the EPS database. Meanwhile, patent—related data are collected from the China National Intellectual Property Administration.

Data on internal expenditures of R&D funds are retrieved from the websites of science and technology departments (bureaus) and statistics departments (bureaus) of various provinces and municipalities in China, as well as the annual statistical bulletins and work summaries of various cities. The establishment time of an NIIDZ is sourced from the website of the Torch High Technology Industry Development Center of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. Data such as the regional GDP, import and export trade volume, balance of the RMB deposits of financial institutions, proportion of added value of the tertiary industry to GDP, number of employees, year-end population, and road freight volume are obtained from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook. Data on the degree of openness and the number of ordinary institutions of higher learning are sourced from the EPS database. The real regional GDP is deflated based on the regional GDP in 2006, which is set as the base period. Missing values are supplemented using the linear interpolation method. The characteristics of the main variables are shown in Table 1.

Model validation

Scientifically rigorous model validation serves as the core prerequisite for ensuring the reliability of causal inference. This study constructs a validation framework across four dimensions—causal identification, robustness testing, endogeneity handling, and spatial model adaptation.The specific logical framework is as follows:

-

Causal Identification: A parallel trend test is conducted via an event study design (Eq. (2) in Section "Causal identification") to assess the consistency of pre-policy trends between the treatment and control groups.

-

Robustness Testing: This includes placebo tests (random assignment of pseudo-treatment groups) 、Propensity Score Matching-Difference-in-Differences (PSM-DID) and exclusion of other innovation-driven development policies (Section "Robustness testing"), addressing random disturbances and selection bias.

-

Endogeneity Handling: Historical postal data are employed as an instrumental variable (IV) to address the self-selection bias in the NIIDZ pilot selection, ensuring the reliability of causal inference (Section "Endogeneity handling").

-

Spatial model adaptation: The applicability of the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) is verified through the LM/R-LM/LR tests (Section "Spatial spillovers from NIIDZs").

Causal identification

One vital precondition for implementing a multiperiod difference-in-differences model is that the trends of the changes in the treatment group and the control group prior to the policy implementation are identical54. In other words, the STI efficiencies of the treatment group and the control group must conform to the parallel-trend assumption before the exogenous policy shock takes place. To test whether there is a parallel trend before the policy shock and to examine the dynamic impact of an NIIDZ on the city’s STI efficiency, we construct Eq. (2) to test the parallel trend hypothesis and draw on Li et al. (2016), who utilize the event study method55:

Specifically, we replace \(did\) in Eq. (1) with dummy variables for several years before and after the establishment of the NIIDZ, with the dependent and control variables remaining unchanged. In Eq. (2), \({D}_{S}\) is a dummy variable for the year in which the NIIDZ was established; s takes a positive value to indicate s years after the NIIDZ was established and a negative value to indicate s years before the NIIDZ was established; and \({\beta }_{s}\) is the impact of the NIIDZ on the city’s STI efficiency. When s is less than 0, s is not significantly different from 0; thus, the parallel trend assumption is verified56.

The time window of s ∈ [− 3,3] is selected to cover a reasonable observation period before and after policy implementation, while avoiding interference from other policies due to excessively long time spans. When s < 0, the parallel trend assumption is validated if all \({\beta }_{s}\) are not significantly different from zero (using t-tests with city-clustered robust standard errors, p > 0.1). Additionally, the event study approach allows for simultaneous analysis of dynamic effects after policy implementation, providing a methodological foundation for the finding in Section "Parallel trend test and dynamic effects analysis" that the effect becomes significant in the 4th year. The test results are visualized through a coefficient distribution map (Fig. 2) with 95% confidence intervals, intuitively demonstrating the temporal variation in effects before and after the policy.

Robustness testing

Placebo testing

Although we include several control variables and control for individual and time fixed effects in a quasii-natural experiment, there may still be uncontrolled city-level characterization factors. To rule out the possibility that the innovation-driven effect of NIIDZs is influenced by other unobserved omitted variables, we conduct an indirect test by randomly generating cities with NIIDZs in the full sample of cities as the experimental group. According to the baseline regression Model (1), the expression for the estimated value of the coefficient β_1 is shown in Eq. (3):

where control represents all observable control variables, δ represents the effect of unobserved omitted variables, and δ is set to 0 to ensure an unbiased estimate of \({\beta }_{1}\). If the city establishing the NIIDZ is randomly generated, then \({\beta }_{1}\)=0. If the estimates of \({\beta }_{1}\) are affected by unobservable omitted variables, then \({\widehat{\beta }}_{1}\) is not zero. To improve the ability of the placebo test to make identifications, following existing studies57,58, we repeat the process of randomly selecting samples 500 and 1,000 times (to satisfy the law of large numbers).

If the placebo test is valid, the estimated values of β̂₁ from 500/1000 repeated samplings should follow a normal distribution centered at 0. The specific criteria are as follows: the mean of the coefficient distribution shows no significant difference from 0 (p > 0.1 in t-test), and the proportion of samplings where the 95% confidence interval covers 0 exceeds 90%.

Propensity score matching (PSM-DID) test

To investigate the impact of NIIDZs on urban innovation efficiency, the ideal approach is to compare the service levels of the same city under policy influence and non-influence. However, it is impossible to observe both states of a city simultaneously in reality. Drawing on existing research59,60, this study employs the Propensity Score Matching-Difference-in-Differences (PSM-DID) method to construct “counterfactual” samples. Using the control variables in the benchmark model, propensity scores are generated through Logit regression, followed by sample matching using three methods: nearest neighbor matching, radius matching, and kernel matching. On this basis, a difference-in-differences model is constructed to identify the impact of NIIDZs on STI efficiency. The PSM-DID test, validated through cross-verification with multiple methods (such as sensitivity tests with different matching radii), further enhances the robustness of research conclusions.

Exclusion of other innovation-driven development policies

China has implemented several innovation-driven development policies at the city level. During the period examined in this research, China introduced the National Innovative Cities Pilot Policy in 2008. By the end of 2020, a total of six batches of pilot cities had been approved, covering 78 cities in 31 provinces (It includes the urban areas of four centrally-administered municipalities, 72 cities at the prefecture level, and two cities at the county level. Data from the website of the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, "Documents of Departments of the State Council"). In 2012, the smart city pilot initiative commenced with the designation of the initial group of pilot cities. Subsequently, the second and third rounds of pilot city selections took place in 2013 and 2014, respectively. Altogether, this policy has encompassed 290 cities across these three selection phases (Data from the website of the Ministry of Housing and Construction of the People’s Republic of China).

With respect to policy content, the pilot policy for national innovative cities aims to increase investments in innovation, transform the results of innovation, optimize the environment for innovation and entrepreneurship, and incentivize innovation and entrepreneurship, whereas the pilot policy for smart cities aims to build an urban innovation system and a physical network system based on intelligent sensing, big data and other technologies to change the city’s capacity and urban behaviour and achieve connotative development. Both the innovative city pilot policy and the smart city pilot policy promote innovation development. The implementation of these policies is closely related to the policies, time period, and spaces examined in this study; thus, these policies may interfere with the driving effect of the NIIDZ on the STI efficiency of the host city.

To control for the impact of the above policies on the estimation results, we construct the following equation based on the baseline model (Eq. 1):

In Eq. (4), \({did}_{ct}^{q}\) and \({did}_{ct}^{w}\) are the difference-in-differences (DID) estimators for the national innovative city pilot policy and smart city pilot policy, respectively. These estimators are included as additional control variables in the benchmark regression. If the direction, magnitude, and significance of the NIIDZ dummy variable coefficients do not change substantially after controlling for the above innovation-driven policies, it can be determined that the findings of this paper are not caused by confounding the effects of the innovative city pilot and smart city pilot policies.

Endogeneity handling

The selection of NIIDZ pilot cities may suffer from "self-selection bias"—cities with better economic foundations and higher technological innovation levels are more likely to be chosen as pilots, leading to correlation between the policy variable and error term in DID estimation. The instrumental variable (IV) approach addresses this by introducing an exogenous variable correlated with NIIDZ establishment but independent of current urban innovation efficiency, thus stripping away self-selection bias. In accordance with existing research61,62, this paper selects the historical postal and telecommunications data of each city in 1984 as the instrumental variable for the establishment of NIIDZs.which satisfies:

-

Correlation: As an early information infrastructure, the layout of the post office system influenced subsequent internet access and the accumulation of innovation infrastructure, establishing a historical transmission chain consistent with the logic of NIIDZ establishment.

-

Exogeneity: The distribution of post offices in 1984 was determined by historical and geographical conditions during the planned economy period, with no direct causal relationship to the current urban economic development or innovation efficiency.

However, the 1984 postal data are cross-sectional data, which creates a dimensional mismatch problem with the panel data of the explained variables and endogenous variables. This paper solves this problem by constructing an interaction term (IV). To be more exact, an instrumental variable is constructed by taking the product of the quantity of post offices per million residents in each city during 1984 and the number of internet users from the preceding year. This particular combination serves as a crucial tool in the analysis, enabling a more robust identification strategy within the econometric framework. This method captures variation across regions and over time, incorporates the idea of difference-in-differences, and can improve the accuracy of instrumental variable estimation.

The logic for testing the validity of instrumental variables is as follows: On the one hand, the correlation test requires that the IV be strongly correlated with the endogenous variable (NIIDZ establishment), which is evaluated by the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic (with a critical value of 10). On the other hand, the exogeneity test requires that the IV be independent of the error term, which is verified by the Kleibergen-Paap LM test for the under-identification hypothesis.

Spatial model adaptation

To identify the spatial spillover effects of NIIDZs on urban STI (Science, Technology, and Innovation) efficiency, it is necessary to select the optimal spatial econometric model through rigorous theoretical analysis and statistical tests, including LM test, R-LM test, and LR test. The LM test detects the presence of spatial lag effects, the R-LM test identifies the significance of spatial lag effects by excluding other interferences, and the LR test compares the goodness-of-fit of different spatial models to determine their applicability63. If all three tests reject the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level, it indicates that the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) cannot be degenerated into a spatial lag model or spatial error model, suggesting that the SDM can be used to capture both direct and spatial spillover effects simultaneously.

Empirical results and analysis

Regression to the base

Table 2 shows the regression results for the effect of NIIDZ establishment on improvements in urban STI efficiency. The regression results of Models (1) and (2) in Table 2 correspond to the full sample of cities; those of Models (3) and (4) correspond to the sample after excluding municipalities; and those of Models (5) and (6) correspond to the sample after excluding municipalities, provincial capitals, and planned cities. The regression results for Models (1), (3), and (5) reflect controlling for city fixed effects only, whereas those for Models (2), (4), and (6) reflect controlling for all variables. The empirical results of Model (1) demonstrate that the coefficient of the variable is significantly positive at the 1% level and remains positive and significant after the exclusion of municipalities, provincial capitals, and planned cities. Taken together, these findings suggest that an NIIDZ has a strong upgrading effect on the efficiency of urban STI and that the influence of the NIIDZ is in line with policy expectations.

Parallel trend test and dynamic effects analysis

Figure 2 presents the results of the parallel trend test, which indicates the magnitude of the estimated parameter \(\widehat{\beta }\) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval. The coefficient estimates before the establishment of the NIIDZ are obviously statistically insignificant. This result indicates no noteworthy difference in the level of STI efficiency between the experimental and control groups before the establishment of the NIIDZ and verifies the parallel trend hypothesis. The dynamic effect shows that from the year when the NIIDZ was established to the 3rd year after its establishment, the driving effect of the NIIDZ on the STI efficiency of the host city was not significant. The coefficient becomes significantly positive (0.097***, p < 0.01) in the 4th year after the policy, which is consistent with the general law of 'construction period—effect period’ of China’s development zone policies64. These results verify the temporal heterogeneity in the driving effect of the NIIDZ on the STI efficiency of the host city as proposed in Hypothesis 2.

The results of robustness tests

The results and analysis of placebo tests

Figure 3 reports the probability density distributions of the estimated coefficient \(\widehat{\beta }\) from 500 and 1,000 simulated regressions. The red curve denotes the probability density distribution of the DID coefficient from the placebo test, while the green curve represents the normal distribution. The horizontal axis shows the estimated values of coefficient \({\widehat{\beta }}_{1}\), and the vertical axis indicates the probability density values. It can be observed that the estimated values from randomly selected samples are centrally distributed around the zero axis, and the estimates generally follow a normal distribution. The mean values of β̂₁ from 500 and 1,000 simulations are 0.003 and -0.001, respectively. The proportions of simulations where the 95% confidence interval covers zero are 92.3% (for 500 simulations) and 96.7% (for 1,000 simulations), exceeding the 90% threshold for valid placebo tests. This leads to the fundamental conclusion that no other unobserved influencing factors exist. In summary, the empirical test results of the impact of NIIDZs on STI efficiency are not affected by other random factors.

Analysis of PSM-DID test results

After propensity score matching, 1,815 observations (retention rate 95.5%), 1,813 (95.4%), and 1,650 (86.8%) were obtained respectively (Table 3), with sample loss primarily attributed to restrictions of the common support interval for propensity scores. The kernel density plots of propensity scores (Fig. 4) show notable differences in kernel densities of PS values between the treatment and control groups before matching, while the kernel density curves of the two groups become highly similar after matching, indicating that the matched samples exhibit close similarity in characteristic variables.

The DID coefficients under the three matching methods are all significantly positive at the 1% level: the radius matching result is 0.0956***, kernel matching is 0.0654***, and nearest neighbor matching is 0.1098***, suggesting that NIIDZs enhance STI efficiency by an average of 6.54%-10.98%. In models incorporating control variables, the R2 increases from 0.252 to 0.336 while the core conclusions remain unchanged, validating the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

Test results of excluding policy interference

Table 4 reports the corresponding estimation results. It can be observed that after controlling for the National Innovative City Pilot Policy and Smart City Pilot Policy, the direction, magnitude, and significance of the coefficients of the NIIDZ dummy variable show no substantial changes. Therefore, the benchmark regression results of this paper exhibit robustness.

Results of endogeneity test

Table 5 shows the estimation results of the instrumental variable approach, with IV as the instrumental variable. All the values are clearly positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that the driving effect of an NIIDZ on a city’s STI efficiency continues to hold after endogeneity is considered. This finding suggests that the regression results of the DID model are not due to sample selection bias. The test value of the Kleibergen-Papprk Wald F for the instrumental variable (IV) is 334.151, which is greater than the empirical value of 10 and leads to a rejection of the hypothesis of underrecognition; the test value of Kleibergen-Papp rk Wald F is 1631.759, which is greater than the empirical value of 10, indicating that the instrumental variable is valid and that the weak instrumental variable problem does not exist (F-test results higher than 10 are currently recognized by the mainstream academic community as the empirical threshold).

Empirical evidence shows that the interaction term between the 1984 post office density and internet user counts satisfies the relevance and exogeneity requirements for instrumental variables, confirming the reliability of the IV design. After controlling for endogeneity, the magnitude of the promoting effect of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency is consistent with that of the benchmark model, verifying the causal reliability of policy impacts. The instrumental variable approach and PSM-DID form a methodological triangular validation, jointly supporting the core conclusion that "NIIDZs significantly enhance urban innovation efficiency" and providing rigorous empirical evidence for policy evaluation.

Heterogeneity test

Heterogeneity of the construction model

To explore the differences in the impact of NIIDZs under different construction models on urban STI efficiency, this study conducts a grouping treatment of the samples. The treatment group, which is based on the actual construction situations of 19 NIIDZs, is divided into two subsamples: 8 NIIDZs are constructed on the basis of a single city, which is defined as the "single-city model", and 11 NIIDZs are jointly constructed by two or more cities and are classified as the "urban agglomeration model"(The 11 city clusters category NIIDZ refers to the southern Jiangsu NIIDZ, Changzhutan NIIDZ, Hangzhou NIIDZ, Pearl River Delta NIIDZ, Zheng Luoxin NIIDZ, Shandong Peninsula NIIDZ, Shenda NIIDZ, Fuxia-Quan NIIDZ, Hewu-beng NIIDZ, Ningwen NIIDZ, and Lanbai NIIDZ.) The 11 city clusters category NIIDZ refers to the southern Jiangsu NIIDZ, Changzhutan NIIDZ, Hangzhou NIIDZ, Pearl River Delta NIIDZ, Zheng Luoxin NIIDZ, Shandong Peninsula NIIDZ, Shenda NIIDZ, Fuxia-Quan NIIDZ, Hewu-beng NIIDZ, Ningwen NIIDZ, and Lanbai NIIDZ.

Columns (1) and (2) in Table 6 report the corresponding results for the two types of subsamples. The driving effects of the NIIDZs constructed under both the single-city model and the urban agglomeration model on urban STI efficiency are significantly positive. However, the driving effect of NIIDZs under the single-city model on the STI efficiency of the cities where they are located is slightly higher than that of the NIIDZs under the urban agglomeration model. The reason for these differences may be that in the actual construction of NIIDZs in city cluster mode, the provincial government generally coordinates their construction and promotes it through the issuance of relevant policies. Moreover, the provincial government encourages competition at the city level through competition tournaments. City-level governments are often constrained by local development and the competitive environment and are more focused on the pursuit of their own interests when they are participating in the construction of NIIDZs, which leads to a lack of satisfactory construction results.

Urban scale heterogeneity

We group the sample cities in the treatment group according to the categorization criteria in the Circular on Adjusting the Criteria for the Division of City Size issued by the State Council of China in 2014. Since the sample size of small cities with a resident population of less than 500,000 is too small, these cities are included as medium-sized cities. Accordingly, the sample cities are categorized into "mega + super", large, and medium-sized cities. Columns (1), (2), and (3) of Table 7 report the estimation results for "mega + super", large, and medium-sized cities, respectively. NIIDZs obviously do not have a significant driving effect on the STI efficiency of "mega + super" cities. However, they have a remarkable driving influence on the STI efficiency of large and medium–sized cities, and the impact on large cities is more noticeable. First, as mentioned above, the agglomeration of human capital and innovation resources created by NIIDZs can compensate for the shortage in innovation resources, promote the diffusion of knowledge and technology, and significantly enhance urban STI efficiency. Second, "mega + super" cities have smaller or even saturated gaps in human capital and innovation resources, and the marginal effect of establishing NIIDZs in these cities is small. This finding suggests that although the establishment of NIIDZs has generally improved the STI efficiency of the cities in which they are located, this effect has been concentrated in large and medium–sized cities and less pronounced in "mega + super" cities.

STI efficiency heterogeneity

To further verify the heterogeneity of the effect of NIIDZs on cities with different levels of STI efficiency, we choose three quantile points of 25%, 50%, and 75% and perform a double difference estimation. The results are shown in Table 8. The regression coefficients of NIIDZs on cities’ STI efficiency are positive and significant at the 1% level at the three quantile points of 25%, 50%, and 75%. The regression coefficient reveals that when the STI efficiency of a city itself is low, the marginal driving effect of an NIIDZ on STI efficiency is large. Moreover, given the gradual improvement in the city’s STI efficiency, the driving effect of the NIIDZ on the STI efficiency of the host city gradually weakens.

Mechanism of action tests

According to the theoretical analysis presented in previous papers, the agglomeration of innovation factors, the optimization of the innovation environment, and the transformation and upgrading of the industrial structure all affect urban STI efficiency. A corresponding mechanism test is performed in this paper to further clarify the internal mechanism through which NIIDZs affect urban STI efficiency.

Clustering effect of innovation factors

The construction of NIIDZs can spur the agglomeration of innovation subjects and innovation factors within cities and can cause scale effects through the concentration of innovation elements to increase the STI efficiency of cities. Therefore, we systematically sort out the theoretical mechanisms by which the establishment of NIIDZs affects urban STI efficiency in terms of three aspects: the VC index of the China Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship Index is used to represent the venture capital agglomeration effect of the city (The China Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship Index is compiled by the Center for Enterprise Big Data Research at Peking University in China. Since 2015, an annual release system has been implemented for this index. The regional innovation index covers all the industrial and commercial registration data of enterprises within the territory of Mainland China from 1990 to the present. With enterprises as the core, and based on the three core elements of entrepreneurs, capital, and technology, it uses objective output-based indicators to achieve a more authentic measurement of the innovation and entrepreneurship vitality of various regions in China in terms of five dimensions, including the number of newly established enterprises, the amount of attracted foreign investment, the amount of attracted venture capital, the number of authorized patents, and the number of trademark registrations. The report has been continuously released for many years and is one of the relatively authoritative regional innovation and entrepreneurship evaluation reports in China); the number of students enrolled in higher education institutions is used to represent the level of human capital; and the human capital density is constructed based on existing research65, i.e., the number of students enrolled in higher education institutions per unit area reflects the level of human capital agglomeration in the city (talent, unit: 10,000 persons/square kilometre). The number of patents and applications per 10,000 people are chosen as indicators of technology factor concentration, and the number of patent applications per 10,000 people is obtained from the State Intellectual Property Office of China.

Table 9 shows the results of the test of the agglomeration effect of innovation factors. The establishment of NIIDZs can further promote the effect of an “agglomeration economy” to concentrate key elements such as venture capital, human capital and technology in or around the zone. Through the support of relevant policies, the input of STI factors has rapidly transformed into STI outputs, leading to effective improvements in the innovation efficiency of STI enterprises in parks and further enhancing improvements in the STI efficiency of cities.

Innovation environment optimization effect

We test the role of NIIDZs in influencing the efficiency of urban STI from three aspects: enhancing the construction of new urban infrastructure, increasing the intensity of intellectual property protection, and increasing the level of marketization. Specifically, the number of international internet users per 10,000 people is employed to characterize the level of new infrastructure development in the city (i.e., the number of households per 10,000 people). The number of international internet users is derived from the EPS database. The number of judgements (ipp, in units) of intellectual property infringement cases by people’s courts in each sample city between 2006 and 2020 is manually searched in the Chinese judicial case database of Beida Faber. This quantity is a direct measure of the number of patent lawsuits filed and heard in court by infringed parties and provides a better measure of the strength of a city’s intellectual property protection. The level of marketization (market) of a city is obtained from the China Marketization Index. Table 10 shows the test results of the optimization mechanism of the urban innovation environment. The results indicate that the establishment of an NIIDZ increases the STI efficiency of the host city through the optimization of the innovation environment as a pathway, which verifies Hypothesis 1 that NIIDZs optimize the urban innovation environment.

Industrial transformation and upgrading effects

The urban industrial structure objectively reflects differences in productivity, resources, and environmental endowment and the factor input structure of different sectors at the city level, resulting in different city types having different STI conditions and spatial layouts. Moreover, adjusting the industrial structure may change the efficiency of urban STI. In this study, referring to existing research62, the industrial structure upgrading index is used to determine the extent to which a city’s industrial structure is upgraded according to the following formula: \(indust\_stru = \sum {indust_{i} \times i(1 \le i \le 3)}\), where \(indust_{i}\) denotes the proportion of the output value of industry i to the total output value. Column (2) of Table 11 provides the results of the examination. The effect of NIIDZs on the index of urban industrial transformation and upgrading is positive and noteworthy at the 1% significance level, with an estimated coefficient of 0.1926. Moreover, the finding that NIIDZs promote the transformation and upgrading of a city’s industrial structure, as proposed in Hypothesis 1, is verified.

Spatial spillovers from NIIDZs

The LM and R-LM tests show obvious spatial error effects in the model and spatial lag effects; therefore, the spatial Durbin model is more appropriate. Next, whether the spatial Durbin model degenerates into a spatial error model or a spatial lag model with the original assumptions of H1: θ = 0 and H2:θ + ρβ = 0, respectively, is determined. According to the LR test results, the original Hypotheses H1 and H2 are rejected, indicating that the spatial Durbin model cannot be generalized to a spatial error model or a spatial lag model. The statistical value of the Wald test passed the 1% significance level test, which still indicates that the spatial Durbin model is the most appropriate model for this study. Therefore, we adopt the spatial Durbin model to empirically examine the spatial spillover effect of NIIDZs. Furthermore, the Hausman test is adopted to determine whether the spatial Durbin model should use fixed or random effects. As illustrated in Table 12, the statistical value of the Hausman test passes the 1% significance level test, leading to a rejection of the original hypothesis and suggesting that the fixed effects spatial Durbin model is a more robust choice. In conclusion, a series of tests demonstrate that the spatial Durbin model with fixed effects is the optimal choice for spatial econometric modelling.

To more intuitively observe the relationship between the spatial spillover effect coefficient and the change in spatial distance, we plot the curvilinear relationship between the two variables (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 5, the spatial spillover effect of NIIDZs on STI efficiency can be categorized into three stages with respect to geographic distance. In the first stage, when the spatial distance from the NIIDZ is within 110 kms, the spatial spillover effect is significantly negative; i.e., the construction of the NIIDZ significantly reduces the STI efficiency of areas within 110 kms of its periphery. The second stage is at a spatial range of 110–410 kms, in which the spatial spillover impact of the NIIDZ is significantly positive and peaks at 360 kms, indicating that the NIIDZ has a noteworthy positive driving effect on the STI efficiency of cities within this range. The third stage is at a spatial range of 410–810 kms. When the spatial distance exceeds 410 kms, the spatial spillover effect of the NIIDZ is no longer significant. The above test results verify the spatial heterogeneity of the driving effect of NIIDZs on urban STI efficiency proposed in Hypothesis 2.

Conclusions and policy implications

Conclusion

This research leverages panel data from 274 Chinese cities spanning 2006 to 2020, applying econometric techniques including the did approach to evaluate how the establishment of NIIDZs) affects urban STI efficiency. The key findings are summarized as follows:

-

①

The policy effect shows significant characteristics of time lag and dynamic reinforcement. In the initial stage of the establishment of the NIIDZ, the role of promoting urban STI efficiency was not prominent. Not until the fourth year of its construction does it begin to have a positive promoting effect. Over time, this effect continues to strengthen, reflecting the gradual release and cumulative characteristics of the policy effect.

-

②

There are significant heterogeneities in the policy impact. In terms of the construction mode, there are differences in the impact of NIIDZs on STI efficiency between the single-city mode and the urban agglomeration mode. In terms of urban characteristics, factors such as the city size and the existing level of STI efficiency lead to the differentiation of policy effects. This finding indicates that the policy effect of an NIIDZ is restricted by the choice of construction mode and the differences in individual urban characteristics.

-

③

The policy action mechanism is clear and definite. NIIDZs improve urban STI efficiency through three major paths: first, attracting and concentrating high-end innovation elements, including resources such as talent, funds, and technologies; second, optimizing the regional innovation environment and improving institutional guarantees and infrastructure; and third, promoting the transformation and upgrading of the industrial structure, thereby accelerating the innovative transformation of traditional industries and the cultivation of emerging industries.

-

④

Spatial differentiation is observed in the policy impact. The impact of an NIIDZ on surrounding areas shows significant characteristics of spatial distance decay: within a range of 110 kms, there is a significant inhibitory effect; within a range of 110–410 kms, the spatial spillover effect is significantly positive and reaches its peak at 360 kms; and when the spatial distance exceeds 410 kms, the spatial spillover effect tends to be insignificant.

Policy implications

First, the establishment of new NIIDZs is supported in central cities in essential economic zones. Given that NIIDZs can have a sustained driving effect on the efficiency of urban STI and can radiate and drive the STI efficiency of neighbouring regions, the promotion of innovation through the establishment of new NIIDZs is currently a feasible option for China’s STI policy. Considering that NIIDZs have better innovation-driven effects in cities with lower STI efficiency and that China’s 23 existing NIIDZs still have an uneven spatial distribution, the country should actively support regional central cities in the central and western regions to establish new NIIDZs based on the existing NHTZs that are more mature in development, build featured-type NIIDZs according to local conditions, and introduce a mechanism for dynamic adjustments and exit assessment to increase the vitality of competition NIIDZs to support benign competition.

Second, we coconstruct a mechanism for the high-end development of NIIDZs. The management system of an NIIDZ should be continuously modified, NIIDZs should be encouraged to introduce management regulations, a management system suitable for its own level of development and development characteristics should be explored, and its management structure should be further optimized. The government should support and guide NIIDZs to increase their capacity for the creation, diffusion and transformation of new knowledge; strengthen the cultivation of new R&D institutions, industrial technology research institutes and other institutions with diversified businesses, such as basic research, applied research, the transformation of achievements and entrepreneurial incubation; and promote the fusion of science and technology with industry. Improvements in innovation ecology should be accelerated; the interoperability of funds, business integration and the circulation of talent should be promoted; a regularized mechanism for the deep docking and joint innovation of a variety of subjects should be established; the deep integration of industry, academia and research should be promoted; and a mission-oriented and benefit-oriented innovation community should be formed.

In this paper, we establish a mechanism for linkage development between NIIDZs and urban STI. The in-depth integration of an NIIDZ with the STI, economic development, and the industrial structure of the host city should be enhanced, exchanges and cooperation among various innovation subjects should be strengthened, and the in-depth integration of science and technology, information, talent and other innovation resources should be directed to form an innovation eco-space conducive to the agglomeration of innovation factors. The supportive role of the NIIDZ in facilitating a city’s STI should be strengthened by actively docking with scientific research institutes, leading enterprises, science and technology parks, colleges, and other STI subjects; the mechanism of resource sharing and synergistic development should be explored; the sphere of influence should be expanded; and the linked development of all subjects and regions should be pursued. Cities should focus on creating an atmosphere of STI; accelerating the convergence of innovation resources, talent, technologies and policies; building NIIDZs as sources of innovation and engines of urban STI; promoting the dominant role of NIIDZs in regional innovation systems; and further enhancing the effect of NIIDZs’ sphere of influence on cities’ innovation efficiency and innovation capacity.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Madsen, J. B., Ang, J. B. & Banerjee, R. Four centuries of british economic growth: The roles of technology and population. J. Econ. Growth 15(4), 263–290 (2010).

Shen, M., Wan, H. Y. & Li, K. J. From, “investment-driven” to “innovation-driven”: The endogenous motivation and transformation impact of the change in the economic growth model. Statist. Res. 36(03), 17–31 (2019).

Zhang, C., Liu, B. & Yang, Y. Digital economy and urban innovation level: A quasi - natural experiment from the strategy of “Digital China”. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1–12 (2024).

Huang, Y., Audretsch, D. B. & Hewitt, M. Chinese technology transfer policy: The case of the national independent innovation demonstration zone of East Lake. J. Technol. Transf. 38, 828–835 (2013).

He, M. The construction of national independent innovation demonstration zones: Strategic positioning, typical characteristics, and path selection. Res. Financial Account. 01, 71–80 (2023).

Li, Q., Wang, M. & Xiangli, L. Do government subsidies promote new-energy firms’ innovation? Evidence from dynamic and threshold models. J. Clean. Prod. 286, 124992 (2021).

Li, Y. & Du, R. Polycentric urban structure and innovation: evidence from a panel of Chinese cities. Regional Stud., 1–15 (2021).

Li, Y., Zhang, X., Phelps, N. & Tu, M. Closed or connected? The economic geography of technological collaboration between special economic zones in China’s Suzhou - Wuxi - Changzhou metropolitan area. Urban Geogr. 44(9), 1995 (2023).

Lasswell, H. D. The Structure and Function of Communication in Society. In Bryson, L. (Ed.), The Communication of Ideas, pp. 37–51. (New York: Harper and Row, 1948).

Ma, Z., Wang, X. & Zhang, Y. Regional innovation policy mix complexity and enterprise technology innovation: evidence from China. Business Process Management Journal. (2025).

Zhang, J. et al. Institutional configuration study of urban green economic efficiency-analysis based on fsQCA and NCA. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 34(2), 1457–1467 (2025).

Schot, J. & Steinmueller, W. E. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Res. Policy 47(9), 1554–1567 (2018).

He, B. et al. Does the cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zones policy affect the urban–rural income gap in China?. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 83(4), 773–792 (2024).

Deleidi, M. & Mazzucato, M. Directed innovation policies and the supermultiplier: An empirical assessment of mission - oriented policies in the US economy. Res. Policy 50(2), 104151 (2021).

Zhang, J., Yang, Z. & He, B. Does digital infrastructure improve urban economic resilience? Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Sustainability 15(19), 14289 (2023).

He, B., Tian, S. & Zhang, X. Does the pilot free trade zone policy increase regional innovation ability? Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 32(4), 576–581 (2025).