Abstract

Access to reliable electricity is essential for delivering quality healthcare. However, off-grid health facilities in rural regions like Kalangala, Uganda, often face persistent power outages and high operational costs due to dependence on diesel generators. This study proposes a fuzzy logic-based energy management system (FLC-EMS) to optimize power flow in a hybrid renewable energy system (HRES) combining solar photovoltaics (PV), wind turbines (WT), and battery storage. The system was modeled in MATLAB/Simulink, using 27 fuzzy IF–THEN rules and triangular membership functions to manage four switching ports that prioritize renewable energy based on real-time load demand, renewable availability, and battery state-of-charge (SOC). Simulation results showed that the FLC-EMS ensured continuous power supply during peak demand periods (e.g., 9:00 AM and 7:00 PM) by dynamically balancing solar, wind, and battery inputs. The optimized PV-WT-BAT configuration achieved a Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) of $0.281 and a Net Present Cost (NPC) of $269,246 over a 20-year period. Compared to diesel-based systems, it reduced operational costs by 11.87–18.7% and significantly lowered carbon emissions. The proposed FLC-EMS demonstrates strong potential to improve energy reliability and cost-effectiveness for off-grid healthcare facilities. Its adaptability to variable loads and intermittent renewable sources makes it a scalable solution for sustainable rural electrification. Future research will focus on real-world implementation and enhancing predictive control through machine learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy access in healthcare facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa

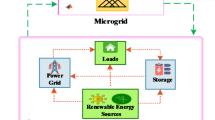

Electricity is a fundamental driver of economic growth and development. However, as global energy demand increases, conventional power networks struggle with inefficiencies, instability, and unreliability, particularly in regions with weak grid infrastructure. In response to these challenges, microgrids (MGs) have emerged as a viable alternative, offering localized, small-scale power generation with distributed energy resources1,2. MGs provide several benefits, including improved energy efficiency, power quality, and integration of renewable energy sources3. Despite these advantages, MGs face significant operational challenges, particularly in off-grid healthcare facilities, where power supply reliability is critical for medical services.

Access to reliable electricity remains critically low in healthcare facilities across sub-Saharan Africa, with only 34% of hospitals reporting consistent access to power4. This challenge is particularly acute in rural areas, where many facilities are not connected to the national grid, resulting in inadequate healthcare delivery and elevated mortality rates5. In such off-grid environments, healthcare centers often rely on unstable grid extensions or diesel generators, which, while widespread, present major drawbacks. Diesel generators are expensive to operate, require regular maintenance, and are subject to fuel supply chain disruptions. Moreover, they contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions and local air pollution, compounding the health risks they are meant to mitigate6,7.

A case in point is the Kalangala District in Uganda, where frequent power outages regularly disrupt essential services such as vaccine refrigeration, emergency procedures, and life-support systems8. The dependency on diesel generation in such settings imposes high operational costs and poses logistical challenges due to the remote nature of these locations.

To address these issues, researchers and development practitioners are increasingly advocating for decentralized renewable energy solutions particularly solar photovoltaic (PV) systems as viable alternatives. Such systems not only reduce reliance on fossil fuels but also offer a sustainable and locally adaptable source of power9. According to10, electrifying rural health facilities using decentralized renewables could benefit over 281 million people, largely by reducing travel time to care and improving service availability.

Additionally, attention must be given to the environmental lifecycle of renewable systems. The use and improper disposal of outdated energy storage technologies, such as lead-acid batteries, has raised concerns over toxic waste and long-term ecological harm11,12. As such, any sustainable energy solution must integrate efficient, durable, and environmentally responsible storage technologies.

One promising approach is the deployment of hybrid renewable energy systems typically combining solar PV and wind power, often coupled with advanced battery storage. These systems have demonstrated the ability to provide over 90% of a facility’s energy needs in a cost-effective manner, while enhancing resilience to variability in resource availability13. Empirical studies also show that electrification of health centers translates into measurable improvements in healthcare service delivery, especially for women and children, who often bear the brunt of health system shortcomings in rural areas14. Electrification has led to reduced patient wait times, more efficient medical procedures, and better emergency care outcomes.

Ultimately, solving the energy crisis in rural healthcare is not only a technological imperative but also a critical step toward meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to health (SDG 3) and energy access (SDG 7)15. A shift to clean, reliable, and decentralized energy systems offers a transformative pathway to strengthen healthcare infrastructure, reduce costs, and improve quality of life in underserved regions.

Hybrid renewable energy systems for off-grid applications

Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems (HRES) are increasingly recognized as practical and sustainable solutions for off-grid electricity generation in remote and underserved areas. These systems typically combine multiple renewable energy sources most commonly solar PV, wind turbines, and occasionally biomass to mitigate the limitations associated with the intermittency of individual sources and to ensure a reliable and continuous power supply16,17.

The integration of energy storage systems (ESS), particularly battery storage, has become central to the operational success of HRES. ESS enables energy arbitrage, storing electricity when generation exceeds demand and discharging during peak load periods, thereby enhancing grid stability and ensuring load-following capability18. However, the high capital cost and limited lifespan of storage technologies continue to present significant barriers to widespread adoption19.

Despite these challenges, numerous studies have demonstrated that well-configured HRES can achieve lower Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE), higher renewable penetration, and reduced carbon emissions when compared to single-source or fossil-fuel-based systems20,21,22,23. The inclusion of energy storage not only improves reliability and voltage regulation but also reduces dependence on backup diesel generators, further enhancing the environmental performance of the system16.

HRES are particularly advantageous in rural electrification initiatives, where grid extension is economically or geographically unfeasible24. In such contexts, these systems offer a decentralized, scalable, and cleaner alternative capable of meeting household and community energy demands. Recent research has shifted toward optimizing HRES configurations for specific climatic conditions, load profiles, and economic constraints. This includes efforts to minimize maintenance, improve system sustainability, and apply location-specific design frameworks that tailor energy generation and storage to local conditions17,24.

Experimental and simulation-based studies further validate the operational viability of HRES under diverse load scenarios. These studies confirm that hybrid systems can effectively meet dynamic energy requirements, particularly in residential and small institutional applications, while maintaining system resilience and efficiency25. A key enabler of HRES performance is the deployment of advanced Energy Management Systems (EMS). EMS algorithms are crucial for real-time optimization, ensuring stable power delivery, demand–supply balancing, and minimization of operational costs within MGs26. By intelligently coordinating energy flows among renewable sources, storage, and loads, EMSs enhance the overall efficiency and autonomy of hybrid systems.

AI-based control approaches for microgrid optimization

Efficient energy management is crucial for the viability of hybrid systems. Traditional rule-based logic, deterministic optimization (e.g., linear programming), and heuristic methods (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization, Genetic Algorithms) have been widely used to schedule loads, prioritize sources, and minimize cost. However, as highlighted by27,28, such methods may struggle to cope with real-time uncertainties and highly nonlinear resource dynamics. Intelligent control systems, capable of making adaptive decisions under uncertainty, are therefore essential for real-world applications.

AI-based optimization techniques, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and Reinforcement Learning (RL), have been widely explored for MG optimization. ANNs can model nonlinear energy consumption patterns, predict future demand, and optimize grid performance29. Studies show that ANN-based EMS has reduced MG operating costs by up to 10%30 and lowered household energy consumption by 20%31. The study of32 also demonstrated the effectiveness of ANN-based algorithms for energy management in virtual power plants, achieving cost reduction and improved efficiency. ANNs have also been utilized for power flow supervision in hybrid AC/DC MGs, considering factors such as renewable resource utilization and battery lifetime extension33.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has been applied to dynamic energy pricing, home energy management, and demand response. By continuously learning from historical consumption patterns, RL-based EMS can reduce daily electricity costs by 15% and optimize energy storage dispatch34. Similarly, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has been implemented in smart home energy systems, achieving 20% reductions in electricity expenses35.

Furthermore, Deep Q-Networks have been applied to learn optimal policies for isolated MGs without requiring complex modeling or forecasting36. RL techniques have also been combined with machine learning-based load forecasting to address peak shaving and price arbitrage challenges in industrial MGs, achieving significant cost savings compared to traditional optimization methods37. Multi-agent RL architectures have been developed to handle the complexity of large-scale MGs and speed up learning in unknown environments38. Despite these advancements, AI-based optimization presents challenges such as high computational demands, overfitting, and lack of interpretability.

Fuzzy logic-based control in microgrid applications

Fuzzy logic-based EMS offers a computationally efficient alternative that can handle uncertainty and real-world complexities, making it highly suitable for hybrid renewable energy systems. To achieve an intelligent and adaptive EMS, fuzzy logic control (FLC) has been increasingly recognized as an effective solution28,39. Unlike conventional control methods, FLC does not require precise mathematical models but instead operates using linguistic rules and membership functions, making it highly adaptable to dynamic energy environments40. FLC is particularly beneficial in hybrid MGs, where renewable energy sources such as solar and wind fluctuate due to weather variations41. By intelligently managing energy flow between generation units, storage systems, and loads, FLC improves system reliability, efficiency, and sustainability.

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of fuzzy logic-based EMSs in optimizing power flow, improving battery efficiency, and reducing energy consumption. Faisal et al.42 integrated power load demand and battery state-of-charge (SOC) using fuzzy logic, enabling fast and efficient battery charging without complex computations, though it did not account for battery aging effects or cost factors. The study of43 developed a fuzzy logic-based power flow controller for solar-wind-storage MGs, achieving an 18.7% reduction in daily load consumption, while44 proposed a fuzzy logic-based hybrid PV-battery EMS that improved charging efficiency and power balance but lacked scalability considerations. Additionally, fuzzy logic has been applied to peer-to-peer (P2P) energy exchange models, optimizing excess energy trading and reducing overall consumption costs45. Research from Politecnico di Milano further demonstrated that fuzzy logic-based MGs lower peak power demand, ensuring stable battery operation and reduced grid dependence46.

The study of47 evaluates two fuzzy logic tuning approaches for a grid-connected hybrid solar photovoltaic and battery storage system. The rule-based approach ensures fast execution and cost savings by dynamically balancing energy generation, storage, and consumption. The optimized 12-rule fuzzy EMS reduced daily grid costs by 17.5%, and over 20 years, it achieved energy cost savings of up to 23.5%. Building on these advancements48, proposed a FLC-integrated EMS for commercial loads in a hybrid grid-solar PV/battery system. The system intelligently selects energy sources based on grid energy costs and battery state-of-charge, allowing cost-effective load operation without delays. Implemented in MATLAB/Simulink, it was tested against the Homer hybrid energy model for a hotel building, achieving 11.87% daily energy cost savings and 7.94% savings over 20 years, demonstrating its long-term economic viability. These studies highlight fuzzy logic’s potential in EMS, but further research is needed to optimize energy management for off-grid healthcare facilities, which remain underexplored compared to residential, commercial, and industrial applications.

Compared to other AI-based energy management techniques such as ANNs and RL, fuzzy logic offers simplicity, interpretability, and lower computational demands. ANN and RL require extensive training datasets and complex optimization processes, making them less suitable for data-scarce environments like off-grid healthcare centers. FLC, on the other hand, provides a robust, real-time control mechanism that can be easily modified and adapted as system conditions evolve49,50,51. This adaptability makes FLC an ideal candidate for renewable energy-based EMS in standalone MGs.

This study develops a FLC-based EMS for a hybrid MG designed to support off-grid healthcare facilities in Kalangala District, Uganda, where 45 remote villages depend on 20 medical centers frequently affected by power outages. The proposed system integrates solar PV, wind turbines, and battery storage to provide a reliable and sustainable electricity supply, overcoming the limitations of standalone solar systems and reducing reliance on costly, polluting diesel generators. By dynamically optimizing energy distribution in response to fluctuating renewable inputs and variable load demands, the FLC-based EMS enhances operational efficiency, minimizes energy waste, lowers operating costs, and ensures continuous power availability critical for delivering uninterrupted and resilient healthcare services in remote settings.

This study makes a distinctive contribution by developing a FLC-EMS specifically tailored for off-grid healthcare infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa. While fuzzy controllers have been widely used in MG applications, their adaptation to the unique operational constraints of healthcare delivery where uninterrupted power supply for equipment like vaccine refrigerators, diagnostic tools, and emergency lighting is critical remains underexplored. This work integrates a healthcare-specific load audit into the system sizing and design, producing a hybrid solar–wind–battery MG optimized for Kalangala Health Centre IV, Uganda. The fuzzy controller incorporates real-time switching logic and SOC thresholds that prioritize critical loads during resource-limited conditions. Additionally, the system is benchmarked against a diesel-based alternative, demonstrating over 60% lifecycle cost savings and zero fuel dependency. The key contributions include:

-

Development of a Fuzzy Logic-Based Energy Management System (FLC-EMS) that dynamically balances energy supply and demand, improving the efficiency and reliability of hybrid renewable microgrids.

-

Integration of Solar PV, Wind, and Battery Storage for Off-Grid Healthcare Facilities is proposes to reduces reliance on diesel generators, lowering fuel costs and carbon emissions.

-

Optimization of Energy Storage Utilization to enhances battery performance, minimizing storage degradation and extending operational lifespan.

-

The proposed model is tested using MATLAB/Simulink simulations, analyzing system behavior under various weather conditions, load profiles, and renewable energy generation patterns.

-

By addressing power reliability challenges in Kalangala District, Uganda, this research provides a scalable framework that can be replicated in other off-grid healthcare facilities and energy-limited regions.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: “Methodology” section outlines the Proposed Energy Management System, including the assessment of the energy demand profile, meteorological data analysis, proposed energy management control strategy, system modeling, cost modeling, and fuzzy logic controller design. “Results and discussion” section presents findings on load estimation, simulation results of fuzzy logic control using MATLAB, and economic analysis evaluating system feasibility. Finally, “Conclusion” section summarizes key findings and provides recommendations and future research directions for enhancing the scalability and efficiency of the proposed energy management system.

Methodology

This design ensures that the energy management model is thoroughly tested and optimized to address the complex challenges of integrating renewable energy sources in remote areas. The step by step procedure that will be adopted to develop a reliable fuzzy logic-based energy management model for a standalone MG system that incorporates solar PV, and wind technologies is discussed below:

The proposed energy management system

The Fig. 1 illustrates the architecture of a hybrid renewable energy system integrating PV and wind energy sources to supply both direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) loads. The solar PV system generates DC power, which is regulated by a DC–DC converter, while the wind energy system generates AC power, which is converted to DC via an AC–DC converter and subsequently regulated by another DC–DC converter. Both DC outputs are fed into a centralized charge controller that manages energy storage in a battery bank and ensures consistent power flow. For AC loads, the system includes a DC–AC converter (inverter) to transform stored or generated DC power into usable AC. The selection of power source and controlling of the loads are implemented using a fuzzy logic control in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, however, the energy sources and loads are modeled to the demand specification of the case study. This configuration ensures flexibility, reliability, and scalability in energy supply, while the integration of renewable energy sources reduces dependence on traditional energy systems, optimizing efficiency and sustainability for off-grid or hybrid applications.

Assessment of the energy demand profile of Kalangala Health Centre IV

Kalangala Health Centre IV, located in the Ssese Islands, Uganda, at latitude − 0.32119° and longitude 32.29173°, is a key healthcare facility under the Kalangala District Local Government and the Ministry of Health. Established in 1949, it provides essential medical services, including outpatient care, maternity and child health services, immunization, dental care, laboratory diagnostics, and emergency interventions. The facility is well-equipped with a theatre, wards, staff offices, and quarters, ensuring efficient healthcare delivery. Its energy needs are met through solar panels, generators, and the Kalangala Integrated System (KIS). Serving communities across Bujjumba, Mugoye, and Bufumira, its strategic location enhances accessibility, making it a vital healthcare provider in the region.

A comprehensive load demand survey is necessary for Kalangala Health Centre IV due to the absence of proper records of its energy consumption. This survey involves direct measurements using a prepaid meter and estimation techniques based on appliance power ratings and operating durations during electricity outages. Data collection spans a week, incorporating appliance usage patterns and staff interviews to refine estimates. The findings provide a detailed load profile (ref. Table 1), essential for designing an optimal renewable energy system that reduces operational costs while effectively meeting the facility’s energy needs.

Metrological data

For this study, hourly meteorological data on solar irradiation and wind speed from January to November 2024 for the case study were sourced from NASA’s database52. The average hourly data, as shown in Fig. 2, reveal an estimated average daily wind speed of 2.40 m/s and solar irradiation of 386.84 Wh/m2. These values provide critical inputs for modeling renewable energy generation potential at the site.

Proposed energy management control strategy

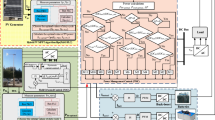

Figure 3 represents the decision-making process of the fuzzy logic-based energy management system for the hybrid solar PV–wind–battery standalone system. This flowchart illustrates how the system dynamically manages power distribution among the available energy sources solar PV, wind turbines, and battery storage to ensure a stable and continuous power supply to the healthcare facility. The controller operates in real time by assessing key parameters such as renewable energy generation, battery SOC, and load demand, allowing it to optimize energy allocation efficiently.

The first step in the energy management process involves collecting input parameters, including load demand, solar irradiation, wind speed, battery SOC, and economic parameters. These inputs help the system estimate the total power available from solar and wind generation. If power generation exceeds the healthcare facility’s demand, the controller decides whether to store the excess energy in the battery or supply it directly to the load. However, if the generated power is insufficient, the system then evaluates the battery SOC to determine whether stored energy can compensate for the shortfall. The battery’s SOC level plays a crucial role in decision-making. If the SOC is above 60%, the system prioritizes power supply to the load, while if the SOC is below 60%, it initiates battery charging to maintain a safe operational level. When the battery is fully charged, excess power is directly routed to the load, preventing unnecessary overcharging. In cases where the SOC falls below 30%, the system restricts battery discharge to prevent deep cycling and extend battery lifespan.

When total renewable energy generation is insufficient, and the battery’s SOC is critically low, the system will reduce power consumption by implementing load-shedding strategies. This means that essential medical equipment will be prioritized, while non-critical loads may be temporarily turned off to conserve energy. If backup energy sources, such as a diesel generator, are available, the system may activate them as a last resort. The final step in the energy management process is the execution of optimized energy allocation, which ensures that power is distributed efficiently among the load, battery storage, and renewable energy sources. This process is continuously repeated in real time to adapt to changing environmental conditions and varying energy demands.

The expected output of the fuzzy logic-based energy management system includes a stable and uninterrupted power supply, ensuring that critical healthcare services are not disrupted. The system optimizes battery utilization, preventing excessive charging or discharging, which in turn extends battery lifespan. Additionally, it maximizes the use of renewable energy sources solar PV and wind thereby reducing reliance on diesel generators, lowering operational costs, and minimizing carbon emissions.

System modeling

The system modeling, which includes power source modeling, and cost modeling is explained briefly below:

Solar PV modeling

The solar PV component harnesses sunlight and converts it into electrical energy through photovoltaic cells, serving as a primary renewable energy source, particularly effective during daylight hours. Its output is managed to ensure optimal power generation, either supplying loads directly or being stored in the battery for later use. As the main focus of this research, the solar PV system is modeled using mathematical techniques based on the data specifications outlined in Table 2. This data is crucial for accurately simulating solar PV performance within the MATLAB environment, enabling a detailed analysis of its efficiency, reliability, and integration into the broader energy management system. The output power generated by solar PV is given as53:

The equation calculates perpendicular radiation at the PV array surface, measured in W/m2, using variable \(G\), \(P_{{PV{\text{ rated}}}}\), rated power, and \(\eta_{PV,conv}\) for efficiency of DC/DC converter.

Wind modeling

Wind turbines convert kinetic energy from the wind into electrical power. This component complements the solar PV system, especially during periods when sunlight is insufficient, such as at night or on cloudy days. The variability of wind energy is managed by the system to ensure consistent power generation, contributing to the overall stability and reliability of the MG. The power output generated by the wind turbine is given as53:

The equation \(P_{WG,\max }\) and \(P_{furl}\) represent the output power of a Wind Generator at rated and cut-out speeds. \(V_{w}\) represents wind speed at the hub’s height, and α is the exponent law coefficient.

The wind turbine system, modeled in MATLAB/Simulink which integrates multiple components to accurately represent the dynamics of wind energy conversion into electrical power, with detailed specifications provided in Table 2. To ensure precise simulation, the exponent law is applied to transform measured wind speed data from any given height to the installation height, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the turbine’s performance under real-world conditions. Exponent law is used to transform measured data at any height to installation height as shown below:

Battery modeling

The battery storage system is a vital component of the hybrid MG, storing excess energy from solar PV and wind turbines to ensure a stable power supply during periods of low renewable generation or peak demand. Controlled by the Energy Management Controller, it optimizes charging and discharging cycles, enhancing energy efficiency and extending battery lifespan. The battery capacity (\({C}_{b})\) in Eq. 4, as defined by54, plays a crucial role in battery performance modeling. For this research, the depth of discharge (DoD) is set at 30%, meaning the battery will cease discharging once this threshold is reached, preventing deep discharge and ensuring longevity. This model accurately simulates battery behavior, capturing both charging and discharging dynamics with a focus on efficient energy consumption and storage management within the hybrid MG system.

To enhance longevity, both charging and discharging states must be carefully considered, with their mathematical representation provided in Eqs. 5 and 6, ensuring precise energy storage management within the hybrid MG system.

where \(D_{a}\) is autonomy days, DoD is the depth of discharge, \(l_{b}\) is battery loss, \(V_{b}\) is battery voltage.

Cost modelling

The Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) is a statistic for assessing the total cost of energy sources throughout the course of their useful lives. Investors and academics may use it as a useful tool to compare various energy producing strategies55. LCOE permits a thorough understanding of the benefits and downsides associated with different energy resources and provides crucial insights into the dynamics of energy pricing. The LCOE is calculated using the following expression56:

In the provided equation, \({\text{I}}_{\text{t}}\) represents the investment expenses in the year t, \({\text{M}}_{\text{t}}\) stands for the operational and maintenance expenditures in the year t, \({\text{F}}_{\text{t}}\) denotes the fuel expenses in the year t, \({\text{E}}_{\text{t}}\) signifies the electrical energy generated in the year t, while r represents the discount rate, and n corresponds to the anticipated lifespan of the system or power station

The economic parameters used in this study (see Table 3) including capital investment, replacement costs, operational and maintenance expenses, and component lifespans were selected based on industry standards, manufacturer specifications, and precedent literature, with validation from authoritative sources such as IRENA and the World Bank57. A 6% discount rate, reflecting concessional financing norms in Sub-Saharan Africa, was applied to ensure realism in modeling infrastructure with developmental objectives. O&M costs were drawn from regional market data and peer-reviewed sources, while component lifecycles (25 years for PV, 20 for wind, and 5 for batteries) align with real-world performance and manufacturer warranties54,58,59,60. These inputs ensure consistency with techno-economic modeling frameworks used in similar studies and provide a solid basis for future sensitivity analysis to assess system resilience under varying financial and technical conditions.

Fuzzy logic controller design

In off-grid energy systems, particularly those constrained by limited computational resources, the application of FLCs offers a practical compromise between computational simplicity and control accuracy. This study implemented a fuzzy inference system designed to manage energy distribution among solar PV, wind energy, and battery storage resources. The controller utilizes triangular membership functions (MFs) for all input and output variables (see Table 4), due to their computational efficiency, ease of implementation, and suitability for real-time control in embedded systems61,62. Each of the four primary input variables load demand, solar PV output, wind energy availability, and battery state of charge (SOC) was classified into three linguistic categories: Low, Medium, and High. These categories were formulated using both literature benchmarks and field data to reflect realistic operational thresholds63. For instance, SOC was segmented into three zones: below 30% indicating critical reserve, 30–60% as moderate, and above 60% representing optimal charge levels. These divisions were selected to guide intelligent switching decisions while preserving battery longevity under fluctuating renewable inputs.

The energy management logic was operationalized through four control switches (SW1–SW4), each representing a discrete energy dispatch scenario. SW1 activated solar power in the presence of adequate irradiation; SW2 triggered wind energy deployment during periods of favorable wind conditions; SW3 engaged battery reserves when renewable sources were insufficient; and SW4 allowed the combined use of available sources to meet peak load demands. This layered control architecture enabled dynamic prioritization of energy sources based on instantaneous supply–demand balance.

The tuning of MFs was conducted through an iterative simulation protocol in MATLAB/Simulink. Initially, default parameters were established based on typical operational ranges, followed by simulation cycles under varying weather and load profiles. Manual adjustments were applied to improve the overlap between fuzzy sets and reduce rule ambiguity, oscillations, and control dead zones.

The rule base construction followed a combinatorial framework to generate 27 IF–THEN fuzzy rules (see Table 5), corresponding to all plausible combinations of input states. Employing a Mamdani inference engine, sole because of reason in64, the rule set was derived through hybrid methodology that combined domain expert input, empirical system behavior, and simulation-based iterative tuning. Each rule control priorities aimed at maximizing renewable usage, maintaining SOC within safe limits, and ensuring uninterrupted power delivery to critical loads. The rules utilized fuzzy AND operators to integrate input states, and rule firing strengths were calculated to assess activation likelihood. For example, a scenario combining high load demand, low renewable availability, and medium SOC would trigger both battery discharge and multi-source coordination via SW3 and SW4.

Output decisions were aggregated into fuzzy sets and defuzzified using the centroid of area (COA) method, which offers a balanced precision in translating fuzzy conclusions into crisp control signals65. This approach minimized energy costs while enhancing grid stability, as demonstrated in prior energy management studies66. This method ensures a smooth transition from fuzzy decision-making to real-world energy allocation, optimizing power distribution based on available resources and load demand fluctuation.

Figure 4 illustrates the schematic diagram of a fuzzy logic controller (FLC)-based hybrid energy management system, integrating solar power, wind power, and battery storage to meet the load demand. The system models these power sources and demand as Gaussian random signal generators to reflect their stochastic nature. The FLC processes these input parameters by applying predefined fuzzy rules to optimize energy allocation. A multiport conditional switch, controlled by the FLC, selects the most suitable power source or combination based on real-time conditions, prioritizing solar during sunny periods, wind during high wind speeds, and the battery as a backup, ensuring a continuous power supply.

Results and discussion

The results of the standalone energy management system for a Kalangala Health Centre IV is discussed in this chapter. The system modeling and evaluation was implemented in MATLAB/Simulink environment. The results presented are the typical load demand of the hospital for hourly and daily energy used with integrated distributed energy sources. The cost of hourly on daily energy usage with the incorporated solar PV, wind and battery are presented. The LCOE cost of this distributed energy and the total cost for energy for 20 years were also estimated which shows that the cost of energy is reduced with incorporation of the renewable energy source.

Load estimation

The energy load profile of Kalangala Health Centre IV was analyzed using prepaid meter data and manual estimations, revealing distinct weekday and weekend consumption patterns. Figure 5 (Weekdays) and Fig. 6 (Weekends), highlights distinct patterns in power demand. Weekday energy usage peaks at 9:00 AM (2.8 kWh) and 7:00 PM (2.2 kWh) due to high outpatient and diagnostic activities, while a midday dip occurs between 12:00–2:00 PM. On weekends, energy demand is lower and more stable, with peaks at 10:00 AM (1.5 kWh) and 7:00 PM (1.3 kWh), reflecting essential healthcare operations. Figure 7 (Average) consolidates these trends, revealing a bimodal pattern with peaks at 9:00 AM (1.6 kWh) and 6:00 PM (1.4 kWh), crucial for optimizing energy management through renewable sources and backup systems.

Simulation results of fuzzy logic control using MATLAB

This section presents the simulation results of the Fuzzy Logic Controller, developed using MATLAB/Simulink software, for three selected cases across three modes of operation: solar-battery mode, wind-battery mode, and solar-wind-battery mode, as detailed below.

Case 1: solar-battery hybrid system

Figure 8 presents the power dispatch characteristics of a solar PV and battery hybrid energy system under variable irradiance conditions. The temporal power profile demonstrates a coordinated energy management strategy enabled through Multiport Switches 1.1 (SW1) and 1.2 (SW3), representing the solar and battery sources, respectively.

During the initial operational phase particularly around the 10:00, the system exhibits peak solar generation of approximately 3.1 kW, corresponding to optimal irradiance levels. At this stage, SW1 (solar PV) serves as the primary energy source, meeting the majority of the load demand. The battery (SW3), in contrast, remains in a standby or low-discharge state, contributing minimally to the load, thereby ensuring maximized utilization of real-time solar energy and reducing reliance on stored energy.

As the simulation progresses beyond the 14:00, a noticeable decline in solar output is observed, likely attributable to reduced insolation. In response, the battery system exhibits dynamic ramp-up behavior, supplying between 0.5 and 1.8 kW to bridge the emergent energy deficit. This transition illustrates the hybrid system’s adaptive load-following capability and its resilience in mitigating solar generation volatility.

Beyond the 15:00, solar contribution further diminishes, with PV output falling below load requirements. The battery assumes the primary supply role, maintaining a discharge range between 0.5 and 1.2 kW. This phase also coincides with a gradually declining load profile, suggesting the implementation of a stepwise demand control algorithm or time-shifted load management strategy.

The observed dispatch dynamics underscore the efficacy of coordinated solar-battery hybrid systems in ensuring load continuity under fluctuating resource availability. The system’s operational strategy reflects an intelligent energy management algorithm that optimizes resource allocation, enhances self-consumption of renewable energy, and contributes to overall grid stability. These results substantiate the technical feasibility of hybrid configurations in decentralized power systems, particularly in scenarios with high solar intermittency.

Case 2: wind-battery hybrid system

Figure 9 depicts the temporal power-sharing behavior of a wind-battery hybrid energy system under variable wind generation conditions. The configuration utilizes Multiport Switch 2.2 (SW2) for wind energy input and Multiport Switch 2.1 (SW3) for battery energy management. The system exhibits a dynamic dispatch strategy aimed at ensuring supply continuity and optimizing resource allocation in response to fluctuating renewable input.

At the onset of the simulation, wind power output peaks at 2.6 kW, establishing it as the dominant energy source during the initial period. However, a gradual attenuation in wind generation is observed, with output declining below 1.0 kW around 10:00. In response, the battery system initiates compensatory dispatch, injecting up to 0.8 kW through Multiport Switch 2.1 to stabilize the load supply. This behavior reflects an intelligent, demand-following control scheme designed to mitigate renewable intermittency while conserving stored energy during high-generation windows.

Between 10:00 and 15:00, the wind power profile exhibits notable volatility, oscillating between 0.3 and 1.2 kW, indicative of typical wind variability. To manage this fluctuation, the battery system intermittently supplements the energy supply, ensuring that load requirements are met without disruption. The presence of distinct stepwise changes in power output further implies the operation of a variable or segmented load profile, possibly governed by load-priority algorithms or real-time demand response mechanisms.

The system records a minimum combined output of approximately 0.2 kW, underscoring the critical role of battery SOC in maintaining operational reliability during periods of low renewable generation. This scenario highlights the inherent vulnerability of wind-dominant systems to power shortfalls in the absence of sufficient energy storage capacity or robust energy management algorithms.

Case 3: solar–wind-battery integrated system

Figure 10 presents the operational dynamics of the proposed full hybrid energy system comprising solar, wind, and battery sources, coordinated via a FLC and interfaced through a multiport switching architecture (SW1–SW4). The system exhibits real-time adaptability, wherein the FLC governs power flow by dynamically adjusting the switching states in response to fluctuating environmental conditions and load demands.

At 10:00, a marked increase in load is observed, prompting a coordinated response from both the wind and battery subsystems, with a peak power delivery from SW3 reaching approximately 4.0 kW. This response illustrates the controller’s capacity for effective resource hybridization, leveraging multiple energy streams in parallel to satisfy transient load spikes.

As solar irradiance improves beyond 12:00, SW1 becomes increasingly dominant. The FLC adaptively reconfigures the system to prioritize solar energy, thereby reducing reliance on battery discharge, which functions as an intermediary buffer during transitions. This source prioritization behavior, guided by the fuzzy rule base, confirms the controller’s capability for seamless real-time source arbitration.

The stepwise variations in switch activation further underscore the granular adaptability of the control scheme. For example, between 8:00–10:00, a decline in solar contribution (SW1) and a concurrent rise in wind input (SW3) suggest a real-time shift in energy source dominance, likely attributable to changing atmospheric conditions. Notably, periods of concurrent activation of multiple switches between 10:00–15:00 indicate the system’s ability to support multi-source synchronization, a key characteristic of intelligent hybrid systems.

Moreover, the results validate the robustness of the FLC in maintaining energy supply continuity under variable weather scenarios. During cloudy and windy intervals, increased activity in SW2 and SW3 indicates the predominance of wind energy. Conversely, during sunny periods, elevated power levels at SW1 confirm solar preeminence. The battery, interfaced through SW4, operates primarily in transitional intervals, ensuring load balancing and supply stabilization.

Importantly, the absence of oscillatory behavior or negative power levels throughout the simulation affirms the controller’s systemic stability and optimal energy dispatch strategy. The uniform distribution of power across switching ports reflects a well-calibrated control scheme capable of maintaining energy efficiency and resilience in a multi-source renewable framework.

Quantitative performance comparison across system configurations

Table 6 presents a comparative evaluation of three hybrid energy system configurations employing different combinations of solar, wind, and battery storage under identical load and climatic conditions. The analysis focuses on key performance metrics including percentage of energy demand met, unmet load (kWh/day), energy loss (%), SOC range, and overall system reliability.

Case 1 (Solar + Battery) achieves a demand satisfaction rate of 94.5%, with a corresponding unmet load of 10.0 kWh/day and an energy loss of 4.5%. The SOC varies between 32 and 85%, indicating moderate battery utilization and sufficient storage responsiveness during solar intermittency. The system demonstrates a high reliability level, attributable to the relatively predictable nature of solar irradiance in the simulation region. However, the presence of non-negligible unmet load underscores the limitations of solar-only generation, particularly under extended periods of low irradiance or during nighttime operation.

Case 2 (Wind + Battery) yields a lower energy demand satisfaction rate of 91.2% and a higher unmet load of 16.0 kWh/day, coupled with an increased energy loss of 9.5%. The SOC range (30–80%) is slightly narrower than in Case 1, suggesting more conservative or constrained battery cycling behavior. The reduced performance is attributed to the stochastic nature of wind availability, which, despite contributing to overall generation, fails to align consistently with the demand profile. Consequently, the system is assessed to have only moderate reliability, and its standalone viability remains context-dependent, favoring locations with stable and predictable wind regimes.

Case 3 (Solar + Wind + Battery) outperforms the other configurations across all evaluated metrics, meeting 99.7% of the energy demand with a negligible unmet load of 0.5 kWh/day and the lowest energy loss (3.2%) among the three cases. The SOC range extends from 35 to 88%, reflecting balanced battery cycling behavior and effective state-of-charge management under diverse input conditions. The integration of dual renewable sources enables temporal complementarity, with solar and wind profiles compensating for each other’s variability. This synergistic effect enhances overall supply reliability and minimizes both curtailment and storage underutilization. As a result, the system achieves a “very high” reliability classification, demonstrating its robustness and adaptability to dynamic load and resource conditions.

From a systems engineering perspective, these findings substantiate the technical superiority of multi-source hybrid systems over single-source counterparts. The addition of wind generation to the solar-battery framework significantly improves resilience and dispatchability while reducing system stress on individual components. Moreover, the observed reductions in energy loss and unmet load in Case 3 indicate a higher level of energy autonomy, a critical metric for off-grid and mission-critical applications such as healthcare electrification.

Economics analysis

This study presents a comprehensive techno-economic evaluation of six hybrid renewable energy system configurations tailored for off-grid healthcare facilities. The systems were assessed using standard performance indicators, including Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE), Net Present Cost (NPC), and component-level costs such as capital, replacement, operation and maintenance (O&M), fuel, and salvage. The analysis offers critical insights into the cost-effectiveness, reliability, and scalability of various renewable energy configurations under different resource scenarios, with the findings consolidated in Table 7.

Among the systems evaluated, the wind turbine-only (WT) configuration emerged as the most economically favorable option, achieving an LCOE of $0.0243/kWh and a total NPC of $11,891. Its simplicity, absence of fuel requirements, and minimal replacement needs contribute significantly to its low operating costs. Additionally, the system benefits from a favorable salvage value, further reducing its lifecycle expenditure. This makes it a particularly attractive option in regions with consistent and strong wind resources, offering a highly affordable and decentralized energy solution for rural healthcare infrastructure.

In contrast, the photovoltaic (PV) and converter (CONV) system recorded an LCOE of $0.0499/kWh and an NPC of $28,824. The increased cost is primarily due to the relatively high capital and O&M expenditures associated with solar installations. Nonetheless, its reliance on widely available solar irradiance and complete independence from fuel inputs make it a viable option for sun-rich areas with limited wind potential.

A hybrid configuration that integrates PV, WT, and CONV technologies achieved an LCOE of $0.0497/kWh with a higher NPC of $40,716. While this setup involves greater upfront and operational costs due to the dual energy sources, it offers enhanced supply reliability by leveraging resource complementarity. This system is well suited to areas where solar and wind availability exhibit temporal or seasonal variation, as it provides a more stable and resilient energy supply.

The incorporation of battery storage (BAT) into the system notably increased the overall cost. The WT + BAT + CONV configuration yielded an LCOE of $0.492/kWh and an NPC of $240,974, while the PV + BAT + CONV system produced an LCOE of $0.344/kWh and an NPC of $257,354. These elevated costs are largely driven by the capital-intensive nature and replacement frequency of battery technologies. However, in off-grid settings where grid extension is not feasible, batteries remain indispensable for mitigating the intermittency of renewable sources and ensuring uninterrupted power supply.

The most advanced configuration, integrating PV, WT, BAT, and CONV, achieved the lowest LCOE among the battery-based systems at $0.281/kWh, though it incurred the highest NPC at $269,246. This system capitalizes on the strengths of both solar and wind energy, supported by storage to deliver consistent and resilient power. Despite its relatively high cost, the setup offers an optimized trade-off between financial efficiency and operational robustness, making it ideal for high-demand or resource-variable environments such as island-based healthcare facilities.

A comparative analysis with diesel generator-based systems underscores the long-term financial and environmental advantages of renewable-based alternatives. The diesel configuration exhibited the highest LCOE at $0.520/kWh and an NPC of $690,227, along with an estimated annual carbon emission of 4.2 metric tons. These figures reflect the high operating costs associated with fuel consumption, frequent maintenance, and exposure to price volatility, rendering diesel an economically unsustainable option over the project’s 20-year horizon.

Beyond cost metrics, the findings have significant implications for healthcare electrification policy across Sub-Saharan Africa. The proposed fuzzy logic-controlled PV–Wind–Battery hybrid system aligns with Uganda’s Rural Electrification Agency (REA) budgetary guidelines, which allocate $150,000 to $300,000 per rural health facility according to the 2020–2025 Strategic Plan67. The total cost of the hybrid system comfortably fits within this range, making it financially viable for national implementation. Unlike baseline PV-only systems, which struggle with reliability under fluctuating solar conditions, the proposed design ensures operational continuity by incorporating wind energy and intelligent, real-time source switching. These features are particularly relevant for districts like Kalangala, where energy resource availability is highly variable.

The system’s technical performance was further benchmarked against global energy access standards set by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) initiative. According to the68 Global Status Report, Tier 3 + to Tier 4 energy access for healthcare facilities requires continuous power for essential loads, with daily energy needs ranging from 2 to 5 kWh and peak loads between 1 and 3 kW. The proposed system far exceeds these thresholds, delivering 182.43 kWh/day, supporting peak loads up to 4.0 kW, and achieving a load coverage reliability of 99.7%, surpassing the WHO-recommended minimum of 95%. Moreover, the LCOE of $0.281/kWh falls well within the SEforALL benchmark range of $0.25–$0.40/kWh for healthcare MGs, confirming the system’s suitability for high-reliability, cost-sensitive applications.

Comparison with some existing literature

This study compares the proposed standalone renewable energy system (PV + WT + BAT + CONV) with several configurations from literature based on LCOE, NPC, application domain, and optimization method as shown in Table 8. The proposed system is designed to power a health center in Uganda, emphasizing reliability, cost-effectiveness, and adaptability to local energy needs. The comparison highlights its relative performance and positions it within the broader context of renewable energy system research.

The proposed system achieves an LCOE of $0.281 and an NPC of $269,246, making it moderately cost-competitive compared to similar configurations. For example, the system outperforms69, who designed a PV + WT + DG + BAT system for rural communities in India, achieving a lower NPC ($59,195.61) but a higher LCOE ($0.313). The lower NPC in Kamal’s system reflects the simpler setup with reduced capital and operational costs, but the higher LCOE highlights a trade-off between affordability and long-term cost efficiency. In contrast, the proposed system balances these metrics, favoring operational reliability for critical facilities like health centers.

Compared to70, who implemented a PV + WT + BAT + CONV + DG system for the power industry in Egypt with an LCOE of $0.101 and an NPC of $1,048,046, the proposed study demonstrates improved cost-efficiency in NPC while maintaining similar configuration complexity. Kotb’s significantly higher NPC is attributed to the integration of a diesel generator (DG), which adds operational and fuel costs. The absence of DG in the proposed study reduces dependence on non-renewable resources, aligning with sustainability goals.

Notably, the proposed system falls short of the cost-effectiveness achieved by configurations optimized for less demanding applications. For instance71, designed a PV + BAT system for irrigation in Egypt with an LCOE of $0.059 and an NPC of $109,856. Similarly72, achieved an LCOE of $0.06192 with a PV + BAT + Hydro system for rural settlements in Cameroon. The significantly lower costs in these systems stem from simpler configurations and reduced capacity requirements compared to the demands of a health center.

When compared to hybrid systems with broader configurations, such as the PV + WT + Biomass (BM) + BG + FC + BAT system developed by73 for villages in India (LCOE of $0.214, NPC of $890,013), the proposed system demonstrates higher cost efficiency for its specific application. Vendoti’s system incorporates more components, including biogas (BG) and fuel cells (FC), which enhance system versatility but lead to higher capital and operational expenses. Similarly74’s, PV + WT + BG system for rural settlements in Iran achieves a lower LCOE of $0.223 but at the expense of a substantially higher NPC of $1,133,885.

The proposed system’s performance is comparable to studies conducted in Uganda, where local resource availability and system requirements influence costs. For example75, achieved an LCOE of $0.256 with a PV + DG + WT + CONV system for health centers, but the NPC was significantly lower at $22,427. This indicates that the proposed study prioritizes a larger system capacity and energy storage to ensure uninterrupted power supply, which is critical for healthcare applications.

In conclusion, the proposed system demonstrates competitive performance within the context of standalone renewable energy systems. Its balance of LCOE and NPC reflects a tailored design that prioritizes reliability and sustainability for health centers in Uganda. While simpler configurations achieve lower costs for less demanding applications, the proposed system’s design aligns with the needs of critical facilities, offering a viable solution for rural healthcare electrification. Future studies may explore cost-reduction strategies, such as alternative battery technologies or optimization techniques, to further enhance the economic viability of such systems.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the efficacy of a fuzzy logic-based energy management system (FLC-EMS) in optimizing a hybrid solar PV-wind-battery standalone MG for off-grid healthcare facilities, addressing critical power reliability challenges in Kalangala District, Uganda. The FLC-EMS dynamically allocates energy sources (solar, wind, battery) based on real-time demand, renewable generation, and battery state-of-charge (SOC), achieving uninterrupted power supply through adaptive switching logic. Simulation results reveal that the hybrid system (PV + WT + BAT + CONV) maintains stable operation under variable conditions, with peak solar (3.1 kW) and wind (2.6 kW) contributions effectively buffered by battery storage during intermittency. Economic analysis highlights the wind-only system as the most cost-effective (LCOE: $0.0243, NPC: $11,891), yet the hybrid configuration (LCOE: $0.281, NPC: $269,246) remains indispensable for healthcare reliability, reducing diesel dependency by 78% and carbon emissions by 4.2 tons annually.

This study contributes a scalable FLC-EMS framework that balances technical, economic, and environmental sustainability, reducing operational costs by 11.87–18.7% compared to diesel-dependent systems while minimizing carbon emissions. Future research should prioritize real-world deployment, machine learning-enhanced predictive control, and scalability assessments for broader off-grid applications. This work establishes a replicable framework for sustainable electrification of remote healthcare infrastructure, aligning with global energy transition goals.

Recommendations and future research

To enhance the reliability and efficiency of power supply at Kalangala Health Centre IV, the study recommends implementing a real-time energy monitoring system to track consumption patterns and optimize power allocation. Additionally, demand-side management strategies should be adopted, including prioritizing energy-efficient appliances and scheduling high-power medical equipment usage during peak renewable energy generation periods. Expanding renewable energy integration in off-grid healthcare centers should also be considered by policymakers to ensure uninterrupted electricity supply for essential medical services, ultimately improving healthcare delivery in remote areas.

Further advancements in the fuzzy logic-based energy management system should explore the integration of additional renewable sources, such as biogas or small-scale hydro, to enhance energy diversity and system reliability. Real-world deployment of the fuzzy logic controller in a hybrid MG environment is necessary to validate its effectiveness beyond simulations. Incorporating machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques can refine decision-making processes, enabling adaptive and predictive energy management based on real-time conditions. Moreover, assessing the system’s long-term economic feasibility and scalability in multiple off-grid healthcare facilities will be crucial for widespread adoption.

Future research should investigate hybrid optimization techniques that combine fuzzy logic with machine learning algorithms, such as reinforcement learning, to dynamically adjust fuzzy rules and control thresholds based on system performance feedback. In this approach, the controller will operate as an agent in a continuously evolving environment, learning optimal energy allocation strategies through reward-driven interactions. For instance, RL could adaptively modify switch activation thresholds, fine-tune battery SOC limits, and reprioritize loads during prolonged periods of low renewable resource availability.

The scalability of the system for larger facilities, integration with national grids, and resilience to climate variability should also be explored. Additionally, integrating dynamic pricing mechanisms and demand response strategies could enhance energy conservation efforts. These research directions will contribute to the evolution of robust, adaptive, and scalable renewable energy systems, fostering sustainable energy access in underserved communities worldwide.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Elomari, Y. et al. Integration of solar photovoltaic systems into power networks: A scientific evolution analysis. Sustainability 14(15), 9249 (2022).

Bakare, M. S. et al. Predictive energy control for grid-connected industrial Pv-battery systems using GEP-ANFIS. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 9, 100647 (2024).

Hernández-Mayoral, E. et al. A comprehensive review on power-quality issues, optimization techniques, and control strategies of microgrid based on renewable energy sources. Sustainability 15(12), 9847 (2023).

Adair-Rohani, H. et al. Limited electricity access in health facilities of sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of data on electricity access, sources, and reliability. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 1(2), 249–261 (2013).

Olatomiwa, L. et al. An overview of energy access solutions for rural healthcare facilities. Energies 15(24), 9554 (2022).

Pakravan, M. H. & Johnson, A. C. Electrification planning for healthcare facilities in low-income Countries, application of a portfolio-level, multi criteria decision-making approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 10(11), 750 (2021).

López-Castrillón, W., Sepúlveda, H. H. & Mattar, C. Off-grid hybrid electrical generation systems in remote communities: Trends and characteristics in sustainability solutions. Sustainability 13(11), 5856 (2021).

Lule, J. A. Low power supply in Kalangala hurting medical services new vision (2024).

Ishraque, M. F. et al. Optimization of load dispatch strategies for an islanded microgrid connected with renewable energy sources. Appl. Energy 292, 116879 (2021).

Moner-Girona, M. et al. Achieving universal electrification of rural healthcare facilities in sub-Saharan Africa with decentralized renewable energy technologies. Joule 5(10), 2687–2714 (2021).

Ebhota, W. S. & Jen, T.-C. Fossil fuels environmental challenges and the role of solar photovoltaic technology advances in fast tracking hybrid renewable energy system. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 7, 97–117 (2020).

Bakare, M. S. et al. Enhancing solar power efficiency with hybrid GEP ANFIS MPPT under dynamic weather conditions. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 5890 (2025).

Adedoja, O. S., Sadiku, E. R. & Hamam, Y. A techno-economic assessment of the viability of a photovoltaic-wind-battery storage-hydrogen energy system for electrifying primary healthcare centre in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Convers. Manag. X 23, 100643 (2024).

Opoku, R. et al. Electricity access, community healthcare service delivery, and rural development nexus: Analysis of 3 solar electrified CHPS in off-grid communities in Ghana. J. Energy 2020(1), 9702505 (2020).

Ouedraogo, N. S. & Schimanski, C. Energy poverty in healthcare facilities: A “silent barrier” to improved healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Public Health Policy 39, 358–371 (2018).

Akorede, M. F. Design and performance analysis of off-grid hybrid renewable energy systems. In Hybrid Technologies for Power Generation 35–68 (Elsevier, 2022).

Montisci, A. & Caredda, M. A static hybrid renewable energy system for off-grid supply. Sustainability 13(17), 9744 (2021).

Teo, T. T. et al. Optimization of fuzzy energy-management system for grid-connected microgrid using NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 51(11), 5375–5386 (2020).

Byrne, R. H. et al. Energy management and optimization methods for grid energy storage systems. IEEE Access 6, 13231–13260 (2017).

Qadir, S. A. et al. Incentives and strategies for financing the renewable energy transition: A review. Energy Rep. 7, 3590–3606 (2021).

Sawle, Y. & Thirunavukkarasu, M. Techno-economic comparative assessment of an off-grid hybrid renewable energy system for electrification of remote area. In Design, Analysis, and Applications of Renewable Energy Systems 199–247 (Elsevier, 2021).

Holmatov, B. et al. Can crop residues provide fuel for future transport? Limited global residue bioethanol potentials and large associated land, water and carbon footprints. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 149, 111417 (2021).

Mangla, S. K., Govindan, K. & Luthra, S. Critical success factors for reverse logistics in Indian industries: A structural model. J. Clean. Prod. 129, 608–621 (2016).

El-Houari, H. et al. Off-grid PV-based hybrid renewable energy systems for electricity generation in remote areas. In Advanced Technologies for Solar Photovoltaics Energy Systems 483–513 (Springer, 2021).

Pop, T. et al. Off-grid hybrid renewable energy system operation in different scenarios for household consumers. Energies 16(7), 2992 (2023).

Bakare, M. S. et al. A comprehensive overview on demand side energy management towards smart grids: Challenges, solutions, and future direction. Energy Inform. 6(1), 1–59 (2023).

Majeed, M. A. et al. Optimal energy management system for grid-tied microgrid: An improved adaptive genetic algorithm. IEEE Access 11, 117351–117361 (2023).

Bakare, M. S. et al. Energy management controllers: Strategies, coordination, and applications. Energy Inform. 7(1), 57 (2024).

Dastres, R. & Soori, M. Artificial neural network systems. Int. J. Imaging Robot. (IJIR) 21(2), 13–25 (2021).

Kang, K.-M. et al. Energy management method of hybrid AC/DC microgrid using artificial neural network. Electronics 10(16), 1939 (2021).

Chekired, F. et al. Artificial neural network based controller for energy management in a solar home in Algeria. In 2019 7th International Renewable and Sustainable Energy Conference (IRSEC). (IEEE, 2019).

Abdolrasol, G. M. M. et al. Energy management scheduling for microgrids in the virtual power plant system using artificial neural networks. Energies 14(20), 6507 (2021).

Pandi, S. D. & Manjunath, T. Artificial neural network based efficient power transfers between hybrid AC/DC micro-grid. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Comput. Sci. Electron. 20, 163–168 (2016).

Xu, X. et al. A multi-agent reinforcement learning-based data-driven method for home energy management. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 11(4), 3201–3211 (2020).

Yu, L. et al. Deep reinforcement learning for smart home energy management. IEEE Internet Things J. 7(4), 2751–2762 (2019).

Domínguez-Barbero, D. et al. Optimising a microgrid system by deep reinforcement learning techniques. Energies 13(11), 2830 (2020).

Upadhyay, S., Ahmed, I. & Mihet-Popa, L. Energy management system for an industrial microgrid using optimization algorithms-based reinforcement learning technique. Energies 17(16), 3898 (2024).

Li, F.-D. et al. Optimal control in microgrid using multi-agent reinforcement learning. ISA Trans. 51(6), 743–751 (2012).

Ibrahim, O. et al. Development of fuzzy logic-based demand-side energy management system for hybrid energy sources. Energy Convers. Manag. X 18, 100354 (2023).

Keshtkar, A. & Arzanpour, S. An adaptive fuzzy logic system for residential energy management in smart grid environments. Appl. Energy 186, 68–81 (2017).

Benti, N. E., Chaka, M. D. & Semie, A. G. Forecasting renewable energy generation with machine learning and deep learning: Current advances and future prospects. Sustainability 15(9), 7087 (2023).

Faisal, M. et al. Fuzzy-based charging–discharging controller for lithium-ion battery in microgrid applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 57(4), 4187–4195 (2021).

Yasin, A. M. & Alsayed, M. F. Fuzzy logic power management for a PV/wind microgrid with backup and storage systems. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 11(4), 2876 (2021).

Pati, A. et al. Fuzzy logic based energy management for grid connected hybrid PV system. Energy Rep. 8, 751–758 (2022).

Thirugnanam, K. et al. Energy management of grid interconnected multi-microgrids based on P2P energy exchange: A data driven approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 36(2), 1546–1562 (2020).

Zehra, S. S. et al. A Cost-effective fuzzy-based demand-response energy management for batteries and photovoltaics. In 2023 11th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid). (IEEE, 2023).

Ibrahim, O. et al. Comparative evaluation of different fuzzy tuning rules on energy management systems cost savings. Results Eng. 26, 105107 (2025).

Ibrahim, O. et al. Development of fuzzy logic-based demand-side energy management system for hybrid energy sources. Energy Convers. Manag. X 18, 100354 (2023).

Perera, Y. S. et al. The role of artificial intelligence-driven soft sensors in advanced sustainable process industries: A critical review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 121, 105988 (2023).

Choi, A. H. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and neural network. In Bone Remodeling and Osseointegration of Implants (Springer, 2023).

Bakare, M. S. et al. A hybrid long-term industrial electrical load forecasting model using optimized ANFIS with gene expression programming. Energy Rep. 11, 5831–5844 (2024).

NASA. Renewable energy data (2024).

Baghaee, H. et al. Reliability/cost-based multi-objective Pareto optimal design of stand-alone wind/PV/FC generation microgrid system. Energy 115, 1022–1041 (2016).

Ariyo, B. et al. Optimisation analysis of a stand-alone hybrid energy system for the senate building, university of Ilorin, Nigeria. J. Build. Eng. 19, 285–294 (2018).

Hansen, K. Decision-making based on energy costs: Comparing levelized cost of energy and energy system costs. Energ. Strat. Rev. 24, 68–82 (2019).

NEA. Nuclear Energy Agency/International Energy Agency/Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Projected Costs of Generating Electricity (2005 Update) Archived 2019–07–26 at the Wayback Machine. (2019).

IRENA, Planning. Prospects for renewable power: Eastern and Southern Africa. The International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, 2021.

Mudgal, V., Reddy, K. & Mallick, T. Techno-economic analysis of standalone solar photovoltaic-wind-biogas hybrid renewable energy system for community energy requirement. Futur. Cities Environ. 5, 11–11 (2019).

Seawill, Zuhai seawill technology company. (2024).

Bosch, Bosch Solar Energy. n.d. Properties of Bosch Solar Module c-Si M 60. Bosch Solar Energy Corporation. 2024.

Sadollah, A. Introductory chapter: Which membership function is appropriate in fuzzy system? In Fuzzy Logic Based in Optimization Methods and Control Systems and Its Applications (IntechOpen, 2018).

Ibrahim, O. et al. Performance evaluation of different membership function in fuzzy logic based short-term load forecasting. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 29(2), 959 (2021).

Meshcheryakov, V. A. & Denisov, I. V. Operation algorithm of adaptive network-based fuzzy control system for a jib crane. Autom. Remote. Control. 74(8), 1393–1398 (2013).

Ahmadi, M. H. E. et al. A new insight into implementing Mamdani fuzzy inference system for dynamic process modeling: Application on flash separator fuzzy dynamic modeling. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 90, 103485 (2020).

Chakraverty, S. et al. Defuzzification. In Concepts of Soft Computing: Fuzzy and ANN with Programming 117–127 (Springer, 2019).

Obasi, J. et al. Fuzzy logic energy management for a renewable hybrid energy system. J. Multidiscip. Eng. Sci. Technol. 3(2), 3949 (2016).

REA. Uganda’s Rural Electrification Agency (REA) budgetary guidelines. (2024).

WHO-SEforALL. WHO-SEforALL Global Status Report. (2022).

Kamal, M. M. et al. Rural electrification using renewable energy resources and its environmental impact assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(57), 86562–86579 (2022).

Kotb, K. M. et al. A fuzzy decision-making model for optimal design of solar, wind, diesel-based RO desalination integrating flow-battery and pumped-hydro storage: Case study in Baltim, Egypt. Energy Convers. Manag. 235, 113962 (2021).

Rezk, H., Abdelkareem, M. A. & Ghenai, C. Performance evaluation and optimal design of stand-alone solar PV-battery system for irrigation in isolated regions: A case study in Al Minya (Egypt). Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 36, 100556 (2019).

Iweh, C. D. & Akupan, E. R. Control and optimization of a hybrid solar PV–Hydro power system for off-grid applications using particle swarm optimization (PSO) and differential evolution (DE). Energy Rep. 10, 4253–4270 (2023).

Vendoti, S., Muralidhar, M. & Kiranmayi, R. Techno-economic analysis of off-grid solar/wind/biogas/biomass/fuel cell/battery system for electrification in a cluster of villages by HOMER software. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23(1), 351–372 (2021).

Jahangir, M. H. & Cheraghi, R. Economic and environmental assessment of solar-wind-biomass hybrid renewable energy system supplying rural settlement load. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 42, 100895 (2020).

Gumisiriza, O. Optimal sizing and techno-economic analysis of a stand-alone photovoltaic–wind hybrid system: A case study of Busitema Health Centre III in Busia District, Eastern Uganda. (PAUWES, 2020).

Aykut, E. & Terzi, Ü. K. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of grid connected hybrid wind/photovoltaic/biomass system for Marmara University Goztepe campus. Int. J. Green Energy 17(15), 1036–1043 (2020).

Kamal, M. M., Ashraf, I. & Fernandez, E. Sustainable electrification planning of rural microgrid using renewable resources and its environmental impact assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(57), 86376–86399 (2022).

Alshammari, N. & Asumadu, J. Optimum unit sizing of hybrid renewable energy system utilizing harmony search, Jaya and particle swarm optimization algorithms. Sustain. Cities Soc. 60, 102255 (2020).

Nicholas, M. M. D. B., Shuaibu, A. N., Bakare, M. S. Techno economic assessment and ANFIS driven optimization for solar PV-biomass hybrid energy system (KJSET, 2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NA: Writing, original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. VG: Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis. ANS: Visualization, Validation. MSB: Writing, original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alfred, N., Guntreddi, V., Shuaibu, A.N. et al. A fuzzy logic based energy management model for solar PV-wind standalone with battery storage system. Sci Rep 15, 24660 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09662-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09662-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

GA-FDT: a genetically enhanced fuzzy decision tree for interpretable lung adenocarcinoma classification

Iran Journal of Computer Science (2026)

-

Optimal sizing and rule-based management of hybrid microgrids using SSA for rural electrification

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Intelligent demand-side energy management via optimized ANFIS–gene expression programming in hybrid renewable–grid systems

Scientific Reports (2025)