Abstract

A potent anticancer drug, doxorubicin (DOX), has substantial off-target hepatotoxicity, which limits its clinical use. The current study aimed to investigate the hepatoprotective effect of aegeline against DOX- induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Four groups of rats were randomly divided into following: Group I- Control (saline), group II - DOX, group III DOX + aegeline (5 mg/kg/p.o.), and group IV DOX + aegeline (10 mg/kg/p.o.). Various biochemical parameters such as alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, oxidative stress markers such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA), nitric oxide (NO), inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and apoptosis markers, i.e. Bax (Bcl-2-associated X protein), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2), caspase-3 and caspase-9 were performed. Additionally, histopathology and molecular docking were performed. Administration of aegeline at both tested doses led to a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in liver enzyme levels such as ALT, ALP, and AST—in rats with DOX-induced hepatotoxicity, indicating improved liver function. Antioxidant defenses were also markedly enhanced in the aegeline-treated groups, as evidenced by increased levels of GSH, SOD, and CAT compared to the DOX-only group. In terms of inflammation, aegeline treatment significantly (P < 0.05) lowered the concentrations of key inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and the transcription factor NF-κB. This suggests a strong anti-inflammatory effect. Regarding apoptosis, the expression levels of pro-apoptotic markers—Caspase-3, Caspase-9, and Bax were notably decreased in the aegeline-treated rats, while levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 were elevated, pointing to a protective role against DOX-induced cell death. Molecular docking analysis further supported these findings, showing favorable interactions between aegeline and several target proteins. Notably, aegeline exhibited the strongest binding affinity with Bcl-2 (− 6.568 kcal/mol), primarily through hydrophobic interactions, suggesting potential molecular targets contributing to its therapeutic effects. The present study accredited the hepatoprotective effect of aegeline (5 and 10 mg/kg) by ameliorating Dox-induced hepatotoxicity in an experimental animal model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver toxicity, also known as hepatotoxicity, is a pathological condition characterized by hepatic cellular damage resulting from exposure to xenobiotic substances, such as pharmaceuticals, environmental toxins, or industrial chemicals. Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a major etiological factor in liver dysfunction, manifesting as a spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from asymptomatic elevations in liver enzymes (transaminitis) to acute or chronic hepatitis, cholestasis, and ultimately, hepatic failure1. Numerous pharmacological classes are implicated in DILI, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-infective agents (e.g., anti-tubercular drugs), antineoplastic agents, hormonal therapies, immunosuppressants, and neuropsychiatric medications. The pathophysiological mechanisms of hepatic injury can be categorized as hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed (exhibiting characteristics of both). Cholestatic injury frequently arises from the parent drug compound or its metabolites, which interfere with hepatobiliary transporter systems essential for bile formation, as well as the secretion of cholephilic compounds and xenobiotics2.

Doxorubicin (DOX) is an orange-red, water-soluble, crystalline solid derived from Streptomyces peucetius. It is highly potent as an anticancer agent and is used in both powder and injectable liquid forms. DOX is a common chemotherapeutic medication used to treat various carcinomas, including lymphomas, leukemias, breast carcinomas, ovarian carcinomas, thyroid carcinomas, and lung carcinomas. It is a member of the anthracyclines class of chemicals3,4. Daunorubicin, an antibiotic that fights tumors in mice, was created from a red pigment taken from the Streptococcus peucetius strain. This Streptococcus strain produced DOX (also known as Adriamycin) through additional genetic manipulation, also referred to as DOX.

DOX has a wide range of therapeutic effects4. Although it is generally known that DOX can penetrate the cell nucleus and disrupt DNA replication by blocking topoisomerase II, the molecular mechanisms behind its anti-cancer activities are complex and not fully understood5. Additionally, DOX produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a result of redox cycling3,6 and harm to the DNA, proteins, and lipids of cells, which results in cell death5.

The liver is one such tissue that DOX adversely affects. Given that up to 40% of patients receiving DOX have increased liver enzymes, liver toxicity is a crucial therapeutic issue7. Furthermore, mitochondrial function is compromised by DOX-induced ROS in the liver, particularly the superoxide anion8. However, the precise processes underlying DOX-induced hepatotoxicity remain unclear. Thus, the primary goal of this study was to investigate the processes underlying DOX-induced liver injury. Interventions to reduce DOX’s toxicity have drawn more interest because side effects limit its utility as an anticancer treatment.

Aegeline is an active compund of the Aegle marmelos plant. The plant’s medicinal properties and the existence of bioactive substances have been thoroughly investigated. A. Marmelos, one of its numerous pharmacological characteristics, is antiproliferative9antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic10antioxidant11antifungal12hypoglycemic13and antidiabetes14. Due to its beneficial medicinal effects, attention must be paid to its development.

The study’s rationale is that until now, no study has reported that aegeline ameliorates Dox-induced hepatotoxicity. In our research, we investigated the beneficial effects of aegeline on Dox-induced hepatotoxicity, focusing on the roles of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and apoptotic pathways.

Methodology

Chemicals

Aegeline (> 98.0%) and DOX (≥ 98%, C₂₇H₂₉NO₁₁, Mol. Wt. 543.52 g/mol) were obtained from MSW Pharma, M.S., India. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, KB3145), interleukin-1β (IL-1β, KLR0119), interleukin-6 (IL-6, KB3068), and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB, KLR0287) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, procured from Krishgen Biosystem, M.S., India. Bcl-2 associated X protein (MSW-BAX), B-cell lymphoma 2 (MSW-Bcl2), caspase-3 (MSW-Cap-3), and caspase-9 (MSW-Cap-9) levels were measured by ELISA kits, procured from MSW Pharma, M.S., India.

Experiment layout

Ten to twelve-week-old male Wistar rats were housed in a central animal facility, temperature-controlled environment (25 ± 2 °C) with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum in Batterjee Medical College, Jeddah. The study rats were obtained from the central animal house facility of Batterjee Medical College Jeddah. The study was conducted with the ARRIVE guidelines15and approved by the Institutional Research Board, Batterjee Medical College, Jeddah (RES-2025-0024). The experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Batterjee Medical College, Jeddah. The rats were given two weeks to become accustomed to their environment before the test.

A total of 24 rats were simply randomized into four groups (n = 6)16,17.

Blood and liver samples were obtained at the final stage of the study for additional biochemical, oxidative stress, apoptotic markers, and histological investigations.

Sample collection and preparation

Following 24 h after the DOX injection, blood specimens were extracted18. The blood was then allowed to clot for 30 min, after which it was chilled for 4 h to remove the serum and subsequently stored at −20 °C to measure various biochemical variables.

The ketamine and xylazine at 50 and 10 mg/kg were used, and scarification of the rats via cervical dislocation, and the liver was removed, cleansed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and dried. Hepatic tissue homogenates were made by homogenizing liver tissue in ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4). After centrifuging the homogenates (REMI Instruments, India) at 825 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, the clear supernatants were removed and stored at −20 °C for later use in estimating hepatic oxidative and antioxidant variables. Immediately after the sacrifice, liver tissue was taken and weighed. An additional liver part was taken out and kept at −80 °C. Histopathology analyses were performed using liver tissues.

Evaluation of serum biochemical profile

The serum specimens were obtained using a bioanalyzer (UV-Shimadzu, India), and the amounts of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and total bilirubin were estimated. All kits were bought via a local vendor (Modern Lab, Wani, M.S., India).

Assay of oxidative stress and antioxidants

Utilising readily accessible sets and following the manufacturer’s directions, the amounts of malondialdehyde (MSW-MDA), catalase (MSW-CAT), glutathione (MSW-GSH), and superoxide dismutase (MSW-SOD) (MSW Pharma, M.S., India) were measured in liver homogenates using a UV spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, India)19.

Assessment of inflammatory markers

IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and NF-κB levels were assessed using standard ELISA kits. ELISA kits are microwell plate-based assays with pre-coated antibodies (Merilyzer Eiaquant, MLS Pvt. Ltd., India)19.

Assay of apoptotic indices

The detection of Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, and Caspase-9 markers was performed using commercially available and standardised ELISA kits, which are specifically designed for the detection of proteins involved in cell death. An ELISA method for detecting specific antigens using antibodies.

Histopathology

Samples of the liver were obtained to evaluate the histological dysregulations caused by DOX. Tissues from the liver were preserved in a 10% formalin solution. The conserved tissues were dehydrated using higher degrees of ethanol. The tissues were then preserved in paraffin wax. Paraffin blocks were cut into 4–5 μm slices by a rotating microtome. These tiny fragments were put on glass slides, stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and viewed at 200X magnification using a light microscope.

Molecular docking

Ligand preparation and optimization

The design and optimization of the synthetic compounds were performed using MarvinSketch (ChemAxon, version 22.13). Two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) molecular structures were subjected to hydrogen atom addition and structural refinement. Following this, conformational analysis was conducted, and the conformer exhibiting the lowest energy was selected for subsequent investigation. The 3D structures (Mol2 files) were prepared for molecular docking using the DockPrep module within Chimera (version 1.17.1, build 42449). This process employed default parameters, including the assignment of protonation states based on AM1-BCC calculations during conjugate gradient optimization.

Protein preparation

Crystallographic structures for key proteins involved in apoptosis and inflammation were obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/): BAX (PDB ID: 4ZIG), BCL2 (PDB ID: 8FY1), CASPASE 3 (PDB ID: 5IAG), and CASPASE 9 (PDB ID: 1NW9). Validation of these structures included assessment of resolution, wwPDB scores, analysis of missing residues within binding sites via PDBsum (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/pdbsum/), and evaluation of backbone dihedral angles using Ramachandran plots (Fig. 1). Residues comprising the active sites were identified and depicted in Table 1. Prior to docking, the raw PDB files were prepared using the DockPrep module within UCSF Chimera. This involved the removal of extraneous residues, the addition of hydrogen atoms, and charge assignment to optimize the structures for subsequent application of the AMBER force field. The refined structures were then exported in PDB format. Conversion to PDBQT format, compatible with AutoDock, was performed using AutoDockTools (version 1.5.6) from The Scripps Research Institute.

Grid parameters

Molecular docking was performed to investigate the binding interactions between a target protein and ligand(s). AutoDockTools 1.5.63 was utilized for docking simulations. Grid parameter, including the definition of grid center and dimensions, was achieved using Chimera and Maestro. For proteins in a co-crystallized state, grid parameters were derived from the orientation of the co-crystallized ligand. In the absence of a co-crystal structure (Apo state), the CASTp6 server was employed to determine the appropriate grid center. In all cases, a consistent grid point spacing of 0.375 Å was implemented (Table 2).

Molecular docking simulation

Molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina (version 1.2.6) (https://github.com/ccsb-scripps/AutoDock-Vina/releases/download/v1.2.6/vina_1.2.6_win.exe) on a Windows operating system20,21. Simulations were conducted in triplicate with varying grid box dimensions to ensure reproducibility and assess the robustness of the docking protocol. Predefined parameters governed the simulations, including central processing unit (CPU) utilization, grid size, search effort, the number of poses generated, and energy constraints. Post-docking analysis involved custom Python scripts, utilizing functionalities from AutoDock Tools, to extract and organize the docking output and generate separate protein and ligand coordinate files. Visualization and analysis of protein-ligand complexes were subsequently performed using Discovery Studio, Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) (https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de/plip-web/plip/index) and MAESTRO visualization programs.

Validation parameters

Table 3 presents the validation parameters employed in this docking study. These parameters include standard values and corresponding protein structures retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank, which serve as benchmarks for validating the proteins selected for the docking analysis.

Visualization

Protein-ligand complex structures were visualized and analyzed in silico. Two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) interaction maps were generated using Biovia Discovery Studio and Maestro (version 12.3, academic edition).

Statistical interpretation

A statistical software application was used for the data evaluation. The resulting values were illustrated as mean ± SE. GraphPad, version 8.0.2, was used to assess normally distributed data by using the Shapiro-Wilk test. After passing the test, apply the One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey`s post hoc test. The level of significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Body weight

Compared to the controls, the DOX-induced group resulted in a significant decrease (P < 0.0001) in body weight throughout the experiment while increasing both absolute and relative liver weight (Fig. 2A-B). According to these findings, aegeline counteracts the significant effects of DOX on the liver [F (3, 20) = 6.407, (P = 0.0032)] and body weight [F (3, 40) = 22.19, (P < 0.0001)] compared to DOX-induced group.

Biochemical parameter

Liver biomarker

The investigation revealed that the DOX-induced group had elevated serum levels of ALT, AST, ALP, and total bilirubin compared to the control group. Both doses of aegeline treatment significanlty reduced the ALT [F (3, 20) = 47.22, (P < 0.0001)], AST [F (3, 20) = 39.06, (P < 0.0001)], ALP [F (3, 20) = 23.09, (P < 0.0001)], and total bilirubin [F (3, 20) = 10.30, (P = 0.0003)] levels, compared to DOX group (Fig. 3A-D).

Oxidative marker

This indicator was utilized to evaluate the activity of antioxidant enzymes. GSH, SOD, and CAT levels were significantly lower in the DOX-induced group than in the control group. Both doses of aegeline markedly increase the GSH [F (3, 20) = 7.22, (P = 0.0018), SOD [F (3, 20) = 6.427, (P = 0.0032)], and CAT level [F (3, 20) = 7.22, (P = 0.0001)] compared to DOX-induced group (Fig. 3A-C). In comparison with a control group, DOX considerably raised the hepatic MDA value. While aegeline at doses markedly lowered the MDA levels [F (3,20) = 7.710, (P = 0.0013)] than the DOX-induced group (Fig. 4A-D).

Estimation of inflammatory markers

The anti-inflammatory effect was assessed using the neuroinflammatory cytokines. Rats treated with DOX exhibited higher levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and NF-κB than control rats. When aegeline (5 and 10 mg/kg) was administered, the amount of NF-κB [F (3, 20) = 20.64, (P < 0.0001)], IL-1β [F (3, 20) = 40.86, (P < 0.0001)], IL-6 [F (3, 20) = 38.51 (P < 0.0001)] and TNF-α [F (3, 20) = 55.44, (P < 0.0001)] markedly decreased than DOX-induced rats (Fig. 5A–D).

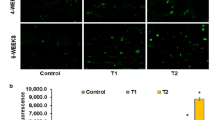

Assessment of apoptosis marker

Comparing the DOX group to the control group, there was a substantial rise in caspase-3, caspase-9, Bax, and reduced Bcl2 activity. On the other hand, aegeline reverses the apoptotic modifications of Bcl2 [F (3, 20) = 8.613, (P = 0.0007)], Bax [F (3, 20) = 15.91, (P < 0.0001)], caspase-9 [F (3, 20) = 15.50, (P < 0.0001)], and caspase-3 [F (3, 20) = 13.52, (P < 0.0001)] in liver tissue caused by DOX. (Fig. 6A-D).

Histopathological injury examination

Histological examination revealed that the liver morphology of rats of control rats was found a normal architecture (Fig. 7A-D). The injection of DOX altered the structure of the liver, showing focal hemorrhage in the peri-portal triad severe. Treatment with aegeline demonstrated reduced hepatocyte cells damage and histological alterations. Compared to the control group, histological scores increased significantly in the DOX group, indicating severe damage. While aegeline treatment significantly decreased histological scores as associated DOX group, indicating a protective effect against DOX in the liver [F (3, 20) = 12.04, (P < 0.0001)] (Fig. 7E).

A-E: Effect of aegeline on histopathological changes. (A) Control-normal architecture (B) Dox- Sever hepatocyte, central vein, sinusoid space, kupffer cells, bile duct cells (Black arrow) (C) Dox + Aegeline-5- Moderate hepatocyte nucleus rounded and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm located radiated (D) Dox + Aegeline-10- Mild architecture of hepatocyte, central vein, sinusoid space, kupffer cell, bile duct cells. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis showed statistically significant findings compared to the DOX-induced liver toxicity: #P < 0.01 Vs the normal group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001.

Molecular docking

The molecular docking studies revealed significant binding energies of Aegeline with various target proteins (Table 4). The binding energy for BAX (PDB ID: 4ZIG) was − 7.47 kcal/mol, indicating strong hydrophobic interactions with residues such as ILE19A, THR22A, LEU26A, and others. For BCL2 (PDB ID: 8FY1), the binding energy was − 6.568 kcal/mol, with hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds involving residues like PHE76A, TRP88A, and TYR98A. CASPASE 3 (PDB ID: 5IAG) showed a binding energy of −6.916 kcal/mol, with hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and π-stacking involving residues such as TYR204A, TRP206A, and ARG207A. CASPASE 9 (PDB ID: 1NW9) had a binding energy of −6.888 kcal/mol, with hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and π-stacking involving residues like LEU244B, ARG258A, and TYR324A. Figure 8 presents the 2D and 3D images of aegeline after molecular docking.

2D and 3D Images of aegeline after molecular docking on protein targets: BAX, BCL2, CASPASE 3, and CASPASE 9. [AutoDock Vina (version 1.2.6) (https://github.com/ccsb-scripps/AutoDock-Vina/releases/download/v1.2.6/vina_1.2.6_win.exe)].

Discussion

Chemotherapy drugs have been linked to liver damage in recent years due to advances in medical knowledge22. By performing metabolic and detoxifying functions, the liver, the body’s largest detoxifying organ, contributes to the maintenance of regular organ function throughout the body. The liver has consequently become a prime target for drug damage. These consist of methotrexate, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and the most often-used hepatotoxic drugs22. Although these medicines are necessary to treat cancer, there are risks and possible side effects associated with them. DOX is hepatotoxic and a potent antitumor drug that combats a range of cancer types4,23. Even though DOX is a commonly used basic chemotherapeutic medication in clinical practice, its effects on the liver cannot be ignored. Previous studies have shown that DOX generates a large amount of ROS during liver metabolism. This results in a redox imbalance, increased oxidative stress, a decreased amount of antioxidant enzymes, and the promotion of inflammation and apoptosis4,24,25. DOX-induced hepatotoxicity, these processes interact with one another and collectively lead to liver damage. The intricate process not only clarifies the potential impacts of DOX on the liver but also provides insights for developing new hepatoprotective techniques that may be more effective in mitigating DOX-induced liver damage26. Thus, research has been conducted on the use of herbal items to avoid the negative effects of chemotherapy27. According to these studies, plant extracts with varying chemical compositions may mitigate the adverse effects of DOX. We postulated that aegeline anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties would help reduce DOX-induced liver damage. In the present study, rats treated with DOX showed a significant decline in their final body weight compared to the control group. Previous studies have revealed that DOX is associated with a significant reduction in rats’ body weight, which is consistent with our findings28. The decrease in body weight gain may have resulted from the chemotherapeutic drug’s direct toxic effects on renal tubules, which reduced water absorption and caused disproportionate salt excretion, leading to dehydration, polyuria, and a decrease in body weight29or it could be the result of gastrointestinal toxicity, which would reduce appetite, food intake, and assimilation29. On the other hand, rats given aegeline (5 and 10 mg/kg) exhibited a discernible increase in body weight. Aegeline at doses of 5 and 10 mg/kg improved organ weight and restored body weight compared to the control group. An important bodily organ, the liver remains engaged in the digestion of food and drugs, detoxification, glucose homeostasis, blood coagulation regulation, albumin production, bile synthesis, and the absorption of vitamins and minerals30. Liver enzymes are naturally present in liver tissues and play a crucial role in regulating various bodily chemical processes, including the metabolism of medications. The liver function test is a collection of liver enzyme tests used to measure and track the integrity of the liver enzymes. ALP, AST, and ALT are commonly used liver function tests30. These tests are useful for establishing a variety of assessments and highlighting a part of the liver where damage may occur, depending on the pattern of elevation30. Some of these tests are related to cellular integrity (such as transaminase), others to functionality (such as albumin), and still others to the biliary tract (such as ALP)31. These liver enzymes are frequently increased in liver disease or injury because they are released from the hepatic cells, which normally store them in the bloodstream32. When the liver is damaged, the enzymes AST and ALT, which reside within hepatocytes, are released, and ALP, which is also present in the cell lining of the liver’s bile ducts, increases32. Chemotherapeutic treatments for cancer, particularly alkylating agents and the infamous DOX, are known to change the way liver enzymes function and raise their levels in the blood33. A rise in serum ALT and AST activity and total bilirubin in DOX-induced rats relative to the adverse influence in this investigation demonstrated DOX-induced hepatotoxicity, indicating significant liver damage. These results are entirely consistent with those of other investigations34,35,36,37,38,39. However, by lowering the levels of total bilirubin and serum ALT, aegeline restored the liver damage. However, aegeline significantly reduced the serum AST levels in the DOX-intoxicated rats, as indicated by the study’s findings. This finding raises the possibility that extra-hepatic sources may be responsible for the high AST levels. Since AST can have extrahepatic activity and is also prevalent in extrahepatic tissues such as skeletal muscle, kidneys, brain, erythrocytes, and lungs, research indicates that ALT is a more accurate and specific indicator of liver illness or toxicity than AST40. Therefore, these extrahepatic sources may be the cause of the markedly high serum AST levels. In line with the findings of earlier research, our investigation revealed that DOX-intoxicated rats exhibited substantial increases in serum AST at 5 and 10 mg/kg aegeline30,41. However, aegeline markedly lowered serum ALT and ALP levels. These results demonstrate aegeline ability to protect against DOX-induced hepatotoxicity. Several different processes contribute to the intricate mechanisms behind DOX-induced hepatotoxicity. According to recent studies, oxidative stress is one important mechanism of oxidation-induced hepatotoxicity42. It has been demonstrated that DOX induces redox homeostasis imbalance, distinguished by a decline in antioxidant defenses and an increase in ROS, which leads to lipid peroxidation and liver injury43,44. SOD and GSH are essential endogenous antioxidants that shield cells from oxidative damage, while MDA is the primary byproduct of lipid peroxidation, which is considered a specific biomarker of oxidative injury45,46. Conforming to earlier findings, the present study demonstrated that DOX induced an increase in liver MDA levels, while decreasing SOD and GSH levels in liver tissues47,48. Aegeline administration significantly improved the DOX-induced increase in SOD and GSH levels and reduced the MDA caused by DOX. According to these results, aegeline therapy can shield the liver from oxidative damage brought on by DOX. The current investigation revealed that the levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-β, TNF-α, and NF-κB) in hepatic tissues were elevated following DOX administration. The production of inflammatory cytokines, which in turn cause hepatic inflammation, is mediated by the stimulation of the cytosolic protein complex (NF-κB) clarified that oxidative damage brought on by DOX poisoning causes the blood to release inflammatory cytokines49,50. Our findings demonstrated that aegeline significantly decreased these inflammatory levels in hepatic tissues due to the antioxidative properties against oxidative stress. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the primary mechanism of DOX-induced liver damage is apoptosis, which is cells’ ordered and spontaneous demise following normal or pathological activation51. The two most significant regulators in the process are Bax (proapoptotic) and Bcl-2 (antiapoptotic), whose ratio can somewhat indicate the level of apoptosis. The final executor of apoptosis is thought to be caspase-3, the hinge component of apoptosis51,52. Consistent with previous findings, the present study demonstrated that DOX administration significantly increased the Bax, caspase-3, caspase-9 and decreased Bcl-2 levels in liver tissues51. Aegeline treatment dramatically decreased the Bax, caspase-3, caspase-9 and increased Bcl-2 by DOX-induced group. These results suggest that aegeline may prevent DOX-induced apoptosis. Additionally, it is advantageous in the inflammatory response in this study due to its inhibitory influence on inflammatory mediators. Changes in the regulation of the most significant clinical liver enzymes and the preservation of normal liver histology further highlight these effects. Furthermore, a molecular docking study confirmed and demonstrated aegeline significant affinity for target proteins. Bax exhibited strong hydrophobic interactions. Bcl-2 showed a lower binding energy due to hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds. Caspase-3 also exhibited lower binding energy due to hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and π-stacking. Caspase-9 had a lower binding energy with hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and π-stacking. These findings indicate Aegeline’s potential therapeutic efficacy, with the observed interactions contributing to binding stability and specificity. DOX accumulates in hepatocytes, resulting in lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and the release of pro-apoptotic factors. The collapse of antioxidant defences leads to a decrease in glutathione, superoxide dismutase, and catalase, while levels of malondialdehyde and nitric oxide rise, further compromising cellular integrity. Simultaneously, NF-κb activation promotes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α), creating a cycle of oxidative and inflammatory damage. At the mitochondrial level, the dynamics shift towards apoptosis as Bax expression increases, Bcl-2 levels drop, and caspase-9 and caspase-3 are activated, culminating in programmed cell death and pronounced hepatocellular damage, evidenced by elevated serum ALT, AST, ALP, and total bilirubin. When aegeline is administered alongside DOX, it appears to disrupt these harmful cascades at various stages. The phenolic moiety of aegeline likely scavenges free radicals, thereby preventing lipid peroxidation and preserving glutathione, SOD, and CAT activities. By stabilising the cellular redox balance, aegeline also reduces NF-κb translocation to the nucleus, resulting in decreased transcription of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. The overall outcome is a significant reduction in inflammatory signaling within the liver. At the same time, aegeline modulates apoptotic proteins: it maintains Bcl-2 expression while inhibiting Bax, caspase-9, and caspase-3 activation, thus preserving mitochondrial integrity and reducing hepatocyte apoptosis. Molecular docking studies indicate that aegeline interacts favourably with Bcl-2 (−6.568 kcal/mol) via hydrophobic contacts, suggesting that direct engagement of these targets is key to its anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects. In summary, aegeline’s capability to restore antioxidant defences, inhibit inflammatory pathways, and sustain anti-apoptotic signaling comes together to protect the liver from DOX-induced damage.

The study’s limitations include its short-term nature and the use of small number of animals. Additional immunochemistry, genetic models, western blotting, and Masson trichome/Sirius red labeling will be required to record collagen in liver sections.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that aegeline protects rats from DOX-Induced hepatotoxicity and may be a helpful therapeutic agent. Aegeline contains antioxidant molecules that work in harmony to prevent DOX-induced oxidative stress, which may be the cause of the observed defensive potential. More research is necessary to determine the exact mechanism by which aegeline mediates its therapeutic impact and enables its usage as a treatment for several other linked disorders.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Björnsson, H. & Björnsson, E. Drug-induced liver injury: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, and practical management. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 97, 26–31 (2022).

Bashir, A. et al. Liver Toxicity, in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2025).

Copyright © StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Gilles Hoilat declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Parul Sarwal declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Dhruv Mehta declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. (2025).

Thorn, C. F. et al. Doxorubicin pathways: pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 21 (7), 440–446 (2011).

Prasanna, P. L., Renu, K. & Gopalakrishnan, A. V. New molecular and biochemical insights of doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity. Life Sci. 250, 117599 (2020).

Aljobaily, N. et al. Creatine alleviates Doxorubicin-Induced liver damage by inhibiting liver fibrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular senescence. Nutrients, 13(1). (2020).

He, H. et al. A multiscale physiologically-based Pharmacokinetic model for doxorubicin to explore its mechanisms of cytotoxicity and cardiotoxicity in human physiological contexts. Pharm. Res. 35, 1–10 (2018).

Aljobaily, N. et al. Creatine alleviates Doxorubicin-Induced liver damage by inhibiting liver fibrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular senescence. Nutrients 13 (1), 41 (2021).

Wided, K., Hassiba, R. & Mesbah, L. Polyphenolic fraction of Algerian propolis reverses doxorubicin induced oxidative stress in liver cells and mitochondria. Pak J. Pharm. Sci. 27 (6), 1891–1897 (2014).

Lampronti, I. et al. In vitro antiproliferative effects on human tumor cell lines of extracts from the Bangladeshi medicinal plant Aegle marmelos Correa. Phytomedicine 10 (4), 300–308 (2003).

Arul, V., Miyazaki, S. & Dhananjayan, R. Studies on the anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and analgesic properties of the leaves of Aegle marmelos Corr. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 96(1–2) pp. 159–163. (2005).

Upadhya, S. et al. A study of hypoglycemic and antioxidant activity of Aegle marmelos in Alloxan induced diabetic rats. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 48 (4), 476–480 (2004).

Nugroho, A. E. et al. Effects of aegeline, a main alkaloid of Aegle Marmelos Correa leaves, on the Histamine release from mast cells. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci., 24(3). (2011).

Sachdewa, A. et al. Effect of Aegle marmelos and Hibiscus Rosa sinensis leaf extract on glucose tolerance in glucose induced hyperglycemic rats (Charles foster). J. Environ. Biol. 22 (1), 53–57 (2001).

Sabu, M. & Kuttan, R. Antidiabetic activity of Aegle marmelos and its relationship with its antioxidant properties. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 48 (1), 81–88 (2004).

Kilkenny, C. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines: Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments. NC3Rs. 2013.

Wali, A. F. et al. Naringenin Regulates Doxorubicin-Induced Liver Dysfunction: Impact on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation9 (Plants (Basel), 2020). 4.

AlAsmari, A. F. et al. Diosmin alleviates Doxorubicin-Induced liver injury via modulation of oxidative Stress-Mediated hepatic inflammation and apoptosis via NfkB and MAPK pathway: A preclinical study. Antioxid. (Basel), 10(12). (2021).

Struck, M. B. et al. Effect of a short-term fast on ketamine-xylazine anesthesia in rats. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 50 (3), 344–348 (2011).

Bukhari, H. A. et al. In vivo and computational investigation of butin against alloxan-induced diabetes via biochemical, histopathological, and molecular interactions. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20633 (2024).

Eberhardt, J. et al. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new Docking methods, expanded force field, and Python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61 (8), 3891–3898 (2021).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31 (2), 455–461 (2010).

Björnsson, E. S. Hepatotoxicity by drugs: the most common implicated agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 (2), 224 (2016).

El-Sayyad, H. I. et al. Histopathological effects of cisplatin, doxorubicin and 5-flurouracil (5-FU) on the liver of male albino rats. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 5 (5), 466 (2009).

Kabel, A. M. et al. Targeting the Proinflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, apoptosis and TGF-β1/STAT-3 signaling by Irbesartan to ameliorate doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity. J. Infect. Chemother. 24 (8), 623–631 (2018).

Yagmurca, M. et al. Protective effects of erdosteine on doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Arch. Med. Res. 38 (4), 380–385 (2007).

Yin, B. et al. Astaxanthin attenuates doxorubicin-induced liver injury via suppression of ferroptosis in rats. J. Funct. Foods. 121, 106437 (2024).

Amin, A. & Hamza, A. A. Effects of roselle and ginger on cisplatin-induced reproductive toxicity in rats. Asian J. Androl. 8 (5), 607–612 (2006).

Rašković, A. et al. The protective effects of Silymarin against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in rats. Molecules 16 (10), 8601–8613 (2011).

Afsar, T., Razak, S. & Almajwal, A. Effect of Acacia Hydaspica R. Parker extract on lipid peroxidation, antioxidant status, liver function test and histopathology in doxorubicin treated rats. Lipids Health Dis. 18, 1–12 (2019).

Adeneye, A. A. et al. Tadalafil pretreatment attenuates doxorubicin-induced hepatorenal toxicity by modulating oxidative stress and inflammation in Wistar rats. Toxicol. Rep. 13, 101737 (2024).

Kwo, P. Y., Cohen, S. M. & Lim, J. K. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Official J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterology| ACG. 112 (1), 18–35 (2017).

Hall, P. & Cash, J. What is the real function of the liver ‘function’tests? The Ulster medical journal, 81(1): p. 30. (2012).

Mudd, T. W. & Guddati, A. K. Management of hepatotoxicity of chemotherapy and targeted agents. Am. J. cancer Res. 11 (7), 3461 (2021).

Grigorian, A. & O’Brien, C. B. Hepatotoxicity secondary to chemotherapy. J. Clin. Translational Hepatol. 2 (2), 95 (2014).

Ahmed, O. M. et al. Camellia sinensis and epicatechin abate doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity in male Wistar rats via their modulatory effects on oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 9 (4), 030–044 (2019).

Moussa, F. I. et al. Protective effect of omega-3 on Doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity in male albino rats. J. Bioscience Appl. Res. 6 (4), 207–219 (2020).

Saleh, D. O. et al. Doxorubicin-induced hepatic toxicity in rats: mechanistic protective role of Omega-3 fatty acids through Nrf2/HO-1 activation and PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β axis modulation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29 (7), 103308 (2022).

El Khouly, W. & Ebrahim, R. Tadalafil attenuates γ-Rays-Induced hepatic injury in rats. Egypt. J. Radiation Sci. Appl. 33 (1), 45–50 (2020).

Mansour, H. M. et al. The anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects of Tadalafil in thioacetamide-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 96 (12), 1308–1317 (2018).

Guevara Tirado, A. Alterations in the Liver Profile and Other Markers of Asymptomatic Patients who Attend Routine Examinations in an Urban Area of Lima, Peru11p. 4 (Revista Virtual de la Sociedad Paraguaya de Medicina Interna, 2024). 1.

Onyilo, P. & Samuel, B. Histomorphological effects of Tadalafil on the liver of adult Wistar rat. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 28 (1), 269–273 (2024).

Tan, B. L. et al. Antioxidant and oxidative stress: a mutual interplay in age-related diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1162 (2018).

AlAsmari, A. F. et al. Diosmin alleviates doxorubicin-induced liver injury via modulation of oxidative stress-mediated hepatic inflammation and apoptosis via NfkB and MAPK pathway: A preclinical study. Antioxidants 10 (12), 1998 (2021).

Song, S. et al. Protective effects of Dioscin against doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity via regulation of Sirt1/FOXO1/NF-κb signal. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1030 (2019).

Mansour, M. A. Protective effects of thymoquinone and desferrioxamine against hepatotoxicity of carbon tetrachloride in mice. Life Sci. 66 (26), 2583–2591 (2000).

Wang, R. et al. Tanshinol ameliorates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats through the regulation of Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-κB/IκBα signaling pathway. Drug design, development and therapy, : pp. 1281–1292. (2018).

Alpsoy, S. et al. Antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects of onion (Allium cepa) extract on doxorubicin‐induced cardiotoxicity in rats. J. Appl. Toxicol. 33 (3), 202–208 (2013).

Mohamad, R. H. et al. The role of Curcuma longa against doxorubicin (adriamycin)-induced toxicity in rats. J. Med. Food. 12 (2), 394–402 (2009).

Kim, S. E. et al. Remission effects of dietary soybean isoflavones on DSS-induced murine colitis and an LPS-activated macrophage cell line. Nutrients 11 (8), 1746 (2019).

Hayat, M. F. et al. Protective effects of Cupressuflavone against doxorubicin-induced hepatic damage in rats. J. King Saud University-Science. 36 (7), 103240 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Citronellal ameliorates doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity via antioxidative stress, antiapoptosis, and proangiogenesis in rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 35 (2), e22639 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of Qingfeiyin in treating acute lung injury based on GEO datasets, network Pharmacology and molecular Docking. Comput. Biol. Med. 145, 105454 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support ( 2025-QU-APC).

Funding

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support ( 2025-QU-APC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Tariq Alsahli, Muhammad Afzal; methodology: Sattam Khulaif Alenezi, Reem Alqahtani, Nadeem Sayyed; first draft of manuscript: Nadeem Sayyed & Tariq Alsahli; Critical Revision of manuscript: Tariq Alsahli, Khalid Saad Alharbi, Sattam Khulaif Alenezi, Reem Alqahtani, Muhammad Afzal; funding: Khalid Saad Alharbi; Analysis: Khalid Saad Alharbi, Sattam Khulaif Alenezi, Reem Alqahtani. All authors read and approved manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsahli, T., Alharbi, K.S., Alenezi, S.K. et al. Aegeline improves doxorubicin-induced liver toxicity by modulating oxidative stress and Bax/Bcl2/caspase/NF-κB signaling. Sci Rep 15, 27203 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09675-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09675-8