Abstract

Fungal genomes encode a huge biosynthetic potential to produce a wide diversity of chemical structures with valuable biological activities remaining silent or under-expressed with standard laboratory conditions. Fungal natural products provide numerous environmentally friendly properties that make them an attractive alternative to the use of synthetic pesticides for the control management of fungal diseases in plants. The main goal of this study was to explore the potential application of a library of natural products extracts from 232 diverse leaf litter associated fungi from South Africa for the discovery of new bio-fungicides. Fungal strains obtained from the MEDINA Fungal Collection were taxonomically classified following molecular and phylogenetic analyses, revealing a high diversity of fungal strains associated with leaf litter from endemic plants of South Africa. A previously designed library prepared following a specific OSMAC approach was employed in this work to evaluate the antifungal activity on a panel of four relevant fungal phytopathogens, using a recently developed HTS platform. The presence of the epigenetic modifier suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) during fungal fermentations in specific formulation media determined considerable changes in the metabolomic profiles that clearly influenced the diversity and quantity of bioactive metabolites, which also affected the activity hit-rates. As a proof of concept, we describe herein the discovery of the novel molecule libertamide upon the addition of SAHA during the fermentation of the strain Libertasomyces aloeticus CF-168990. Libertamide showed antifungal potential to control Zymoseptoria tritici, the causal agent of septoria leave blotch. As result of the study, we show that leaf litter from South Africa is still an untapped source of new fungal species with large biosynthetic potential to produce promising candidates for the discovery of new natural fungicides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant pathogens are the most important cause of crop losses in agriculture worldwide. Fungal phytopathogens exhibit a broad range of host plants, leading to devastating ecological and economic damages1,2,3. Among the most significant genera of fungal phytopathogens are Blumeria spp., Botrytis spp., Colletotrichum spp., Fusarium spp., Magnaporthe spp., Melampsora spp., Puccinia spp., Ustilago spp. and Zymoseptoria spp., which are included in the top ten of the most problematic phytopathogenic fungi4. The preferred strategies to control and manage these fungal diseases involve the use of chemical pesticides. Nowadays, synthetic fungicides are widely employed due to their efficiency in controlling fungal infections and their critical role in preventing the spread of diseases. However, excessive use of these agrochemicals can lead to severe negative impact on both environmental and human health2,3. Moreover, the application of chemical pesticides is strictly regulated to guarantee the quality and safety of agricultural products. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a new effective generation of fungicides from natural sources that can contribute to crop protection in a more sustainable agriculture.

Microbial natural products are considered a valuable source of novel bioactive molecules with a wide range of applications in medicine, food industry and agriculture5,6,7. They exhibit important properties such as biodegradability, biocompatibility and a large variety of modes of action, which make them a very attractive alternative for the control and management of plant diseases2,3,7. In particular, fungi have been extensively explored for the discovery of new bioactive compounds due to the huge biosynthetic capability encoded in their genome6,8. Numerous fungal secondary metabolites have been identified as potential biopesticides, mostly belonging to phenolic, terpenoid and alkaloid chemical classes2,7. Griseofulvin and dechlorogriseofulvin, isolated from various endophytic strains such as Penicillium canescens zjqy610 and Xylaria sp. f0010, present strong inhibitory effects against relevant phytopathogens such as Botrytis cinerea, Blumeria graminis, Colletotrichum orbiculare, Corticium sasakii, Didymella bryoniae, Magnaporthe grisea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum9,10. Similarly, compounds such as sterols, have shown antifungal activity on Bipolaris sorokiniana, a common root rot pathogen of wheat and barley crops11. Additionally, epoxycytochalasin H and cytochalasins N and H, produced by the endophytic strain Diaporthe sp. By254, exhibit strong inhibition of Bipolaris sorokiniana, Bipolaris maydi, Botrytis cinerea, Rhizoctonia cerealis, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Fusarium oxysporum12. Finally, bioactive compounds strobirulins, identified from a culture of the basidiomycete Strobilurus tenacellus, have played a key role in the development of the β-methoxyacrylate class of relevant agriculture fungicides13,14.

Fungi are ubiquitous microorganisms than can colonize multiple ecosystems15. Specifically in terrestrial habitats, fungi play an important role in carbon and nutrient cycling through the decomposition of organic material. The process of leaf litter decomposition is a highly complex process that requires the presence of diverse microorganisms, where fungi are an essential element because of their ability to degrade recalcitrant components presented in leaf litter matter such as cellulose, lignin and suberin16,17,18. Consequently, communities associated with leaf litter harbour a significant number of rare and unique fungal species16,17,18. This fungal community is dominated by Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, especially saprotrophic cord-forming fungi, both considered to possess a rich secondary metabolic potential15. Several previous works have reported the biodiversity of leaf litter fungi in South Africa, mainly associated with Proteaceae (proteas) and Restionaceae (restios). South Africa is considered one of the biodiversity “hotspots”, including areas such as the Cape Floral Kingdom that is one of the smallest but most biodiverse biomes, dominated mainly by endemic plants19,20,21.

Despite the high fungal biosynthetic capability to produce a large variety of bioactive natural products, their potential remains mostly unexplored for many strains because of remaining silent under standard laboratory culturing conditions. OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) is a culture-based approach commonly applied for enhancing secondary metabolite expression of microorganisms. This approach involves the use of multiple nutritional and cultivation conditions such as, different media with diverse carbon and nitrogen sources, variations in shaking and aeration, modifications of pH levels and temperature, as well as the addition of elicitors such as epigenetic modifiers8,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Numerous reports have demonstrated the relevance of media composition in the induction on the production of many fungal secondary metabolites. Previous studies with nutritional arrays revealed that the solid-state-fermentation (SSF) using a rice-based medium provided highly complex and diverse metabolite profiles22,23,26. Epigenetic modifiers were also shown to effectively activate silent biosynthetic pathways during fungal fermentations8,27,28,29. More specifically, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) is considered one of the most widely used histone deacetylase modifiers for the induction of the secondary metabolite production in fungi8,22,27,28,29.

Our previous results from an OSMAC study with 232 fungal strains cultured in 10 different liquid and solid-based fermentation conditions, including the presence and absence of SAHA, confirmed that variations in the medium composition and the addition of SAHA significantly impacted on the metabolomic profiles of a broad diversity of leaf litter associated fungi22. Therefore, the main objectives of this study were to taxonomically characterize deeper in detail this group of talented 232 fungal strains isolated from leaf litter samples collected in South Africa, and to evaluate the potential of their extracts, generated from the OSMAC approach, as a source for the discovery of new bioactive natural products to control fungal phytopathogens. To archive this, its bioactivity profiling was assessed by a High-Throughput Screening (HTS) against a panel of four relevant fungal phytopathogens (Botrytis cinerea, Colletotrichum acutatum, Fusarium proliferatum and Magnaporthe grisea)30, which allowed us to identify the most interesting antifungal profiles towards the characterization of their potentially new bioactive secondary metabolites.

Results

Biodiversity of the fungal population

The 232 fungal strains isolated from leaf litter samples collected in South Africa used in this study were obtained from the MEDINA Fungal Collection. A phylogenetic analysis combined with Blast identification using ITS1-5.8-ITS2 and 28 S rDNA sequences completed previous morphological classification of the studied strains in 11 different classes, 34 orders, 83 families and more than 154 genera. Pleosporales (n = 98), followed by Helotiales (n = 25), Hypocreales (n = 12) and Chaetothyriales (n = 9) were the most represented orders. The remaining 88 fungal strains were widely distributed among other 30 orders. Within Pleosporales, fungal strains were distributed in 59 genera from 24 families, being Didymellaceae (n = 20), Phaeosphaeriaceae (n = 15), Didymosphaeriaceae (n = 8) and Cucurbitariaceae (n = 8) the most representative ones.

Phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood for 28 S rDNA sequences of leaf litter associated fungi from South Africa. Major taxonomic orders are labelled using differential colour coding. Clade maximum likelihood bootstrap values are indicated on the branches (> 50%). Yellow stars highlight the potential new species.

From the total of 154 different genera included in the study, 108 were represented by only one strain. Furthermore, the comprehensive molecular identification highlighted a large number of strains whose ITS rDNA sequences showed similarities lower than 95% with any previously published sequences in public databases, confirming the high taxonomic diversity of these leaf litter associated fungi. Thus, a total of 69 strains (30%) were classified as tentative new species that will be described in future works (Fig. 1 and Table S1). Some examples of strains suggested as potentially novel species included Acrospermum sp. CF-166111 isolated from leaf litter of mountain fynbos of Protea repens, Corticium sp. CF-166036 from mountain fynbos Protea laurifolia, Leptosphaerulina sp. CF-168994 from coastal fynbos Diosma subulata, Scolecobasidium sp. CF-164484 from coastal fynbos Chrysanthemoides monilifera, Neoanthostomella sp. CF-164451 from coastal fynbos Sideroxylon inerme, Alfoldia sp. CF-169033 from lowland fynbos Rafnia cf. trifloral and Tarchonanthus camphoratus, Melnikomyces sp. CF-164291 from leaf litter of culm restio or Clavulina sp. CF-164389 from leaf litter of wild olive (see full list in Supplementary Information, Table S1).

HTS platform activity characterization against four fungal phytopathogens

The previously described 2,362 extract library from leaf litter fungi was tested in a HTS platform of microdilution assays against four phytopathogens selected according to their impact on global agriculture: Botrytis cinerea, responsible of gray mold disease in several important crops; Colletotrichum acutatum, the causative pathogen of anthracnose disease; Fusarium proliferatum, a pathogen associated with the dry rot of garlic bulb; and Magnaporthe grisea, the causative agent of rice blast disease. To assess the bioactivity of each fungal extract, absorbance and fluorescence readouts were used to determine the percentage of conidial germination inhibition (% INH). Instead of defining a fixed 50% threshold of conidial germination inhibition for selecting active extracts, we applied a statistical analysis with JMP® software in hit selection. The distribution of activities was evaluated to test the normality of the data and to identify outliers as potential hits. The distributions of the populations of hit for each phytopathogen are highlighted in Fig. 2.

Botrytis cinerea microdilution assay

The screening results based on absorbance and fluorescence data were represented in two different histograms (Figs. 2a-b). Both readouts exhibited a symmetrical and normal distribution, as indicated the boxplots with central values around 0% INH and zero z’ score. Graphics display a wide bell-shaped distribution reflecting a high variability in the activity data but allowing the differentiation of hits from the main population. Statistical analysis showed extracts with % INH > -53% (z’ score > -1.5) as outliers in the upper quartile from absorbance data (Fig. 2a, black dots at the upper-right) and % INH > -41% (z’ score > -1.5) for fluorescence (Fig. 2b), highlighting them as the hit population. The criterion for hit selection was stringent to prioritize high-quality hits, where only extracts with activity greater than − 53% INH in both readouts were considered hits. Based on this criterion, a total of 113 active extracts (4.78% hit-rate) from 60 fungal strains were identified as hits against B. cinerea.

Colletotrichum acutatum microdilution assay

Statistical analysis of antifungal activity showed a normal distribution of the data, with the absorbance boxplot slightly shifted to the left (non-activity/overgrowth), distribution that was normalized with the z’ score transformation around zero (Fig. 2c). Histograms exhibited extracts with % INH > -16% in the upper quartile of both boxplots (z’ score > -1.5 for absorbance and z’ score > -0.75 for fluorescence), corresponding to the outlier population (Figs. 2c-d). However, this percentage of inhibition was very low and insufficient to select the most potent active extracts. Therefore, a more stringent hit-selection criterion was applied with a cut-off of 50% INH and z’ scores > -2 for both readouts, allowing to differentiate the upper quartile outliers from the normal population. This second criterion aimed to prioritize the selection of highly active candidates, resulting it in only 29 active extracts (1.23% hit-rate) that corresponded to 12 fungal strains.

Fusarium proliferatum microdilution assay

Activity distribution showed again a symmetrical bell-shaped curve indicating a normal distribution of data. Figure 2e shows the absorbance boxplot with a leftward shift at the activity axis, suggesting the overgrowth of this phytopathogen. Data were also normalized by z’ score as previously shown in the C. acutatum assay. However, fluorescence-based activity distribution was not affected as showed clustered data around 0% INH and zero z’ score (Fig. 2f). The outlier population was highlighted from % INH > -13.92% (z’ score > -1.25) for absorbance and % INH > -16.61% (z’ score > -0.75) for fluorescence. However, hit selection criteria remained stringent as previously performed for C. acutatum, where only extracts with more than 50% of inhibition were considered hits (upper quartile outliers), resulting in the selection of 36 active extracts as hits (1.52% hit-rate) corresponding to 13 fungal strains.

Magnaporthe grisea microdilution assay

The microdilution assay against this phytopathogen revealed a unique pattern of antifungal activity with a non-symmetrical distribution in both assay readouts. On the one hand, fluorescence data distribution showed a short interquartile (length of the box), indicating small data variations, but with two hit populations highlighted in the upper quartile (binormal distribution) (Figure S1). On the other hand, absorbance data did not follow a normal distribution, exhibiting a large bell-shaped curve extended from − 100–100% of activity (Figure S1a) which prevented discrimination of hits. When active extracts with more than 50% INH were selected, a high number of hits (n = 420, 17.78% hit-rate) was identified. This hit population was studied in detail and most of these active extracts corresponded to BRFT fermentations (n = 202), which were further analyzed by Mass Spectrometry to reveal the presence of fatty acids in most of them. When these extracts were not considered, the new activity histograms showed a normal and symmetrical distribution with two hit populations (Figs. 2g-h). The first group of active extracts supported by absorbance and fluorescence data was prioritized as containing the most potent hits. This selection corresponded to activities higher than − 87% INH in both assays (z’ score > -2.25 for absorbance and z’ score > -3.5 for fluorescence). Following this criterium, 41 active extracts (1.74% hit-rate) from 18 fungal strains were identified as hits, hits that were explained by the presence of known bioactive metabolites in subsequent dereplication. That is why a second outlier hit population was further studied to identify potentially new antifungal molecules. The fluorescence-based activity boxplot highlighted this second population of outliers (Fig. 2h), despite they were not statistically distinguished from the mean population observed in the absorbance data (Fig. 2g). This hit population included a total of 213 extracts (9.02% hit-rate) with more than 50% of inhibition of M. grisea. This activity group corresponded to fermentations of 82 fungal strains in more than one condition, being 32 strains common to other phytopathogens.

Distribution of antifungal activity based on absorbance (left column) and fluorescence data (right column) against (a-b) Botrytis cinerea B05.10, (c-d) Colletotrichum acutatum CF-137177, (e-f) Fusarium proliferatum CBS 115.97 and (g-h) Magnaporthe grisea CF-105765. The x-axis shows the range of percentage of inhibition and the corresponding z’ score values, while the y-axis shows the frequency of occurrences.

In summary, the screening campaign against the four phytopathogens generated a total of 340 active extracts corresponding to 117 fungal strains. Among them, 7 strains showed a broad-spectrum of activity against the four fungal phytopathogens, 25 strains were active against more than one target and 85 strains showed inhibition on specific plant pathogens (Fig. 3).

Chemical dereplication of active extracts

The 340 active extracts were selected for chemical dereplication of known active compounds. The LC-HRMS analysis identified tentatively a total of 92 known molecules with high chemical diversity in 187 active extracts obtained from 68 of the strains (Fig. 4). The distribution of the dereplicated molecules revealed that 62 compounds were detected in single strains, whereas only 30 were common to more than one strain. The molecules most frequently identified were stemphyltoxin I, preussomerin B, palmarumycin C15, palmarumycin C16 and mellein. Palmarumycins, including palmarumycin B1, B9, C12, C13, C15 and C16, described as phytotoxic, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic compounds, were the most represented family of bioactive compounds. Only five tentatively dereplicated compounds were only detected in fermentations with SAHA: 7-chloro-6-methoxymellein, cordycerebroside A/B, funicone, nomofungin and quinolactacin A2. Whereas N-deoxyakanthomycin and exophillic acid were the unique molecules found in extracts with antifungal activity from conditions without SAHA.

Known molecules tentatively dereplicated by HRMS analyses in the active extracts from leaf litter fungal strains. Compounds are shown according to their production in absence of SAHA (blue), in presence of SAHA (orange) and produced in both conditions (green), tentatively supporting the observed antifungal activity.

Differential production of antifungal activities in the presence of SAHA

The presence of SAHA in fungal fermentations clearly increased the number of active extracts against B. cinerea and M. grisea (Fig. 5a and Table S2). For example, the number of active extracts against B. cinerea increased from 11 hits in non-supplemented fermentations to 76 hits in presence of SAHA. However, the opposite effect was observed for C. acutatum and F. proliferatum, where fermentations with SAHA provided fewer number of active extracts.

Distribution of active extracts against each phytopathogen according to the culture conditions; (a) the presence or absence of SAHA during the fermentation process and (b) the fermentation medium. none = fermentations without SAHA were active, common = fermentations with and without SAHA were active, SAHA = fermentations in presence of SAHA were the active one.

To characterize in detail these differences, the chemical profiles of these hits where SAHA induced a new antifungal activity were compared to identify differential production profiles. This analysis revealed two categories based on the effect of SAHA on the secondary metabolite profiles:

-

(i)

Fungal fermentations with clear enhancement by SAHA of the production levels of specific compounds: We observed the increase in the production levels of known bioactive metabolites in 27 active extracts that could associated to the effects of SAHA. Figure 6a-d; Table 1 show some interesting examples with significant modulation of specific metabolites that could correlate to the antifungal activity observed against the phytopathogens. The strain Curvularia sp. CF-166183 that produced 11-hydroxycurvularin, resorcylide and curvularin in BRFT medium, showed enhanced production levels of these three compounds in the presence of SAHA (Fig. 6a). Other examples include the increase of the peak area corresponding to bisdechlorodihydrogeodin and asterric acid when Oidiodendron sp. CF-166187 was grown in BRFT with SAHA (Fig. 6b), the two fold increase of the production of stemphyltoxin I in YES medium with SAHA by the strain Pyrenochaetopsis leptospora CF-164269 (Fig. 6c), or the improvement in the production of ascomycone A by Forliomyces sp. CF-164290 when was cultured in YES medium with SAHA (Fig. 6d).

-

(ii)

Bioactive compounds that were only produced in the presence of SAHA: The addition of SAHA during fungal fermentations also modified the secondary metabolite profiles of some strains, promoting the production of unique molecules (Fig. 7a-d; Table 2). For example, the production of 7-chloro-6-methoxymellein by Pseudocoleophoma sp. CF-164448 was only observed in the presence of SAHA. Figure 7a shows the LC-HRMS profiles of this strain in LSFM medium, highlighting a small peak at 4.26 min (peak number 9) that corresponds to this antifungal compound only detected in LSFM with SAHA. In addition, this molecule was also detected in the extract of the same strain cultured in solid medium BRFT with SAHA, which also showed inhibitory effects on the germination of B. cinerea and M. grisea conidia. Another example is the strain Sarcostroma sp. CF-166091, that produced hyalodendrin and diorcinol only when was cultured in BRFT with SAHA (Fig. 7b), inducing the inhibition of B. cinerea. Moreover, the antifungal activity detected from the extract of the strain Pyrenochaeta nobilis CF-169016 in BRFT with SAHA could be correlated to the induction of infectopyrone in the presence of SAHA (Fig. 7c), although in vitro testing of the purified molecule will be required to confirm this activity. Finally, the strain Fusarium sp. CF-164444 also showed significant differential chemical and bioactivity profiles after SAHA addition. This strain produced two possible related molecules lucilactaene and 13α-hydroxylucilactaene in LSFM and BRFT fermentation media. However, the production of possible lucilactaene in BRFT is only detected in presence of SAHA (Fig. 7d).

Differential production of antifungal activities by medium composition

Variations in carbon and nitrogen sources during fermentation process also significantly influence the expression of bioactive secondary metabolites. Figure 5b shows the distribution of the active extracts based on the fermentation media, being the solid-based medium BRFT the most productive to generate activities against B. cinerea and C. acutatum. Active extracts against B. cinerea were obtained from fermentations in the five media: BRFT (n = 39), SMK-II (n = 22), LSFM (n = 20), YES (n = 17) and MCKX (n = 15) (Figure S2). Similar results were obtained for C. acutatum active extracts. In contrast, the best fermentation media to obtain activities against F. proliferatum and M. grisea were the liquid media LSFM and SMK-II, respectively. The most productive conditions for activities against F. proliferatum were LSFM (n = 12), being followed by BRFT (n = 9), YES (n = 6), MCKX (n = 5) and SMK-II (n = 4). Finally, non-significant differences were found between the fermentation media in the case of active extracts against M. grisea.

The differential metabolite production in these active extracts has been studied in some strains. One example is the LC-HRMS profiles of the extracts of the strain Chalara sp. CF-164331 grown in six fermentation conditions, which were active against M. grisea (Fig. 8). On one hand, two related unidentified molecules C13H13ClO6 and C13H13ClO5 were detected in all the conditions but with different production levels. A significant increase in the peak area was observed in LSFM with SAHA. On the other hand, fermentations of the same strain in SMK-II medium (both with and without SAHA) produced in addition the macrocyclic mycotoxin emestrin. The production of this compound was enhanced by the addition of SAHA, that consequently increased the inhibitory effects of this extract. Finally, fermentations in BRFT medium changed again the chemical profiles, with the production of two additional metabolites (C19H23N5O5 and C18H24O8) that might be related to its activity against M. grisea.

Production of selected activities in fungal fermentations

Many active extracts were not associated with known compounds by HRMS that explained their observed antifungal activity. Eleven of those most potent extracts were prioritized for scaled-up cultivation, fractionation and detailed analysis of their chemical composition. Strains were grown under their original fermentation conditions using both the original small scale in EPA vials format and flask scaled-up format to generate enough material for a first deconvolution of their active components.

The scaled-up cultivation and the HPLC fractionation enrichment of some strains allowed us to identify the presence of known bioactive compounds not previously detected in the original small scale extracts due to their low production. This was observed for L-783277 by the strain Neoconiothyrium sp. CF-164281, AS2077715 by Scleroconidioma sphagnicola CF-166058 and gliovictin and hyalodendrin by the strain Alfoldia sp. CF-168984.

The active extracts against M. grisea and B. cinerea obtained from the strain Anthostomelloides leucospermi CF-166110 in MCKX and SMK-II media with SAHA were also analyzed. In addition to the presence of cytochalasin H in these extracts, chemical dereplication showed more complex metabolite profiles in the semipreparative HPLC profiles from its fermentations in SMK-II in absence and presence of SAHA (Figure S3). The addition of the elicitor clearly influenced the production in flask of other related cytochalasins. Moreover, the bioactivity-guided fractionation indicated that the different cytochalasins were responsible for the inhibition of M. grisea, whereas ternatin was the responsible for the B. cinerea inhibition. In addition, the related strain CF-166109 showed very similar HPLC profiles where cytochalasins, heptelidic acid, anhydrosepedonin and ternatin could also be identified.

The weak activity against B. cinerea of the strain Coniothyrium sp. CF-164471,that was only observed when grown in MCKX with SAHA, could not also be explained initially by any known molecule in the crude extract. However, HPLC preparative fractionations of their flask fermentations with and without the elicitor, revealed a clear modulation of the metabolite profiles (Fig. 9). After NMR identification of the peaks with related molecular formulae to the active peak, the strain clearly produced a family of known bioactive compounds Sch-217048, Sch-218157, Sch-378161 and pleosporin A, with different production levels. Fractionation profiles showed that Sch-378161 (0.93 mg/L) eluted at 23 min with 60% of acetonitrile and Sch-217048 (3.1 mg/L) at 24.5 min with 64% of acetonitrile in MCKX medium, whereas in the presence of SAHA, different related compounds could be detected: pleosporin A (0.23 mg/L) eluted at 23 min with 62% of acetonitrile and Sch-218157 (2.3 mg/L) at 24 min with 64% of acetonitrile. All four purified compounds were tested against the panel of four phytopathogens, where IC50 (inhibitory concentration) values could only be calculated for Sch-218157, confirming the poor inhibition observed for B. cinerea with IC50 = 111.6 µg/mL in the fluorescence-based assay. However, the absorbance-based assay revealed a low potency of the compound that required a higher concentration to inhibit B. cinerea. The other three compounds showed IC50 > 160 µg/mL against the four phytopathogens tested.

The potent activity of the strain Ramusculicola sp. CF-166025 against M. grisea when cultured in SMK-II with SAHA was found to be associated to a family of compounds with molecular formulae C17H22O4 and C17H22O3, not detected in the absence of SAHA, where an enhancement on the production levels of compounds with formulae C17H20O3, C17H22O3 and C17H22O2 was also observed in flasks (Figure S4). Further scaled-up production and bioassay-guided fractionation analyses would be required to confirm that the antifungal activity corresponds to of this family of potentially new compounds.

Another example of interest was the absence of known compounds in the active extracts against B. cinerea and M. grisea obtained from the strain Equiseticola sp. CF-164483 in BRFT, SMK-II and YES media in the presence of SAHA. The scaled-up fermentation and fractionation finally detected a family of aspochalasins related compounds (C24H37NO4 & C24H35NO3) which were identified as responsible for the antifungal activity detected in the different fractions. Further chromatographic steps from a larger scaled-up fermentation will be required to isolate and purify these compounds in order to be able to determine their chemical structures and to characterize their biological activity in detail.

Discovery of the antifungal libertamide

The strain Libertasomyces aloeticus CF-168990 showed specific inhibition of B. cinerea in the original extracts of the strain when cultured in MCKX and BRFT media, but only with SAHA. No known compound could be chemically dereplicated in its crude extracts. The scaled-up cultivation of the strain in flasks, and further bioassay-guided fractionation (eluting at 29 min with 80% of acetonitrile), followed by LC-DAD-HRMS analysis and NMR spectroscopy, allowed the discovery of a new compound of molecular formula C16H27NO2 ([M + H]+ at m/z 266.2119) (see structural elucidation section in Supplementary Information, S5-S15 and Table S3). This pyrrolidine derivative was associated with antifungal activity, named herein as libertamide (Fig. 10). When its m/z ion was extracted in the metabolomic profiles of the crudes we found that this compound was in fact produced in both MCKX and BRFT media, with and without SAHA, but with different production yields: 188 mg/L in MXCK medium, 229 mg/L in MCKX + SAHA, 303 mg/L in BRFT medium and 395 mg/L in BRFT + SAHA. The presence of libertamide was thus confirmed also in the inactive extracts obtained without SAHA, but in much lower concentrations that explained its lack of activity.

The antifungal profile of libertamide was evaluated against a wider panel of seven phytopathogenic strains. Dose-response curves (DRC) were performed at concentrations ranging from 160 µg/mL to 0.31 µg/mL where IC50 were determined. The most potent activity was obtained against the phytopathogen Zymoseptoria tritici CBS 115943, with values ranging from 0.91 µg/mL for the absorbance-based assay to 1.30 µg/mL for the fluorescence-based assay (Table 3, Figure S16). Additionally, its cytotoxicity in HepG2 cell line was determined from a DRC starting at 40 µg/mL to 0.078 µg/mL, where ED50 (effective dose) was 25.77 µg/mL (Table 3, Figure S17). In consequence, concentrations from 2 to 20 µg/mL of libertamide exhibited high inhibition on Z. tritici without any cytotoxic effect. Its antifungal potential was also extended to the human pathogens Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans, but activity was residual with all minimal inhibitory concentrations higher than 160 µg/mL, the maximum concentration tested (data not shown).

Discussion

Decomposer fungal communities associated with leaf litter have been extensively studied because of their remarkable biodiversity. They include a high proportion of unique and rare species playing essential ecological roles16,17. These fungal species contribute significantly to the decomposition of organic matter, a crucial process for nutrient cycling in terrestrial ecosystems18. One of the objectives of this study was to explore and characterize in detail the antifungal potential of a highly diverse group of fungal strains isolated from leaf litter samples collected in various habitats in South Africa. A phylogenetic analysis combined with molecular identification allowed to improve the initial classification of 232 fungal strains22. In line with the reported prevalence of ascomycetes in this habitat, Ascomycota was the most abundant phylum (89%), most probably due to their capacity to degrade complex plant components15,31. The high number of taxonomic classes, orders, families and genera confirmed the complexity and richness of fungal communities associated with these leaf litter ecosystems16,17,18. Molecular identification techniques such as DNA barcoding and phylogenetic analysis revealed that a significant number of 69 strains (30%) could be potential yet undescribed species (Table S1). Further morphological studies and phylogenetic analyses with multiple housekeeping genes will be required to determine their taxonomic position as newly discovered taxa. Findings have confirmed the huge potential of leaf litter associated communities as an excellent source of novel and unique fungal strains, in particular the leaf litter associated to South African endemic plants belonging to Proteaceae and Restionaceae families16,17,18,19,20,21,31.

New fungal species represent an opportunity to access to undescribed biosynthetic potential that might lead to the discovery of novel bioactive compounds. HTS phytopathogen profiling allowed the identification of bioactive extracts, from which prioritized hit populations with high antifungal potential were determined following statistical approaches. Higher bioactivity hit-rates were obtained against M. grisea (10.75%), many of them were associated with the presence of fatty acids in extracts from their cultivation in the solid medium BRFT, such as linoleic acid, linolenic acid, 11-hydroxylinolenic acid, 1-linolenoyl-sn-glycerol, 1-monolinolein and 1-oleoyl-sn-glycerol. The reported antimicrobial properties of these fatty acids such as linoleic acid, linolenic acid and monolinolenins, including inhibitory activity against fungal phytopathogens such as Rhizoctonia solani and Pythium ultimum, might support these results observed for M. grisea32,33. Lower hit rates were obtained for the other phytopathogens, ranging from 4.78% in B. cinerea, to 1.52% and 1.23% in F. proliferatum and C. acutatum, respectively.

Overall, more than 55% of the active extracts contained major occurring compounds that corresponded to 92 known bioactive molecules (187/340 hits), including 60 identified known molecules in a previous untargeted metabolomics study of the extracts22, in addition 32 antifungals could also be identified after manual evaluation of the HRMS profiles of all active extracts. Thus, most of the strains that showed a broad-spectrum of activity were supported by the identification of known bioactive molecules (Table S2). Compounds of the spirodioxynaphthalene class, represented by preussomerins and palmarumycins, were those most frequently identified in several Phomatodes nebulosa and Cryptocoryneum spp., exhibiting activity against the four phytopathogens and the liver cancer cell line HepG2. This chemical class includes metabolites produced by a great diversity of fungi, described as antifungal agents against the fungal phytopathogens Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium oxysporum and Pyricularia oryzae34; The phytotoxin stemphyltoxin I, described as produced by Stemphylium spp35. –36, was detected in several related Pleosporales showing also a broad-spectrum activity; The related polyketides mellein, 4/3-hydroxymellein and 7-chloro-6-methoxymellein, described with antifungal activity against fungal phytopathogens37,38, can explain the activity observed against B. cinerea and M. grisea in 6 of the fungal strains; Similarly to myoricin, that was already reported to be produced by fungi and to present antifungal activity39. In general, many of the broad-spectrum activities could be explained by the presence of more than one known bioactive molecule (Table S2), such as lecanorin and hyalodendrin, already described as cytotoxic and antimicrobial agents40,41,42, and that herein showed significant inhibition of the four phytopathogens tested, although further studies on the antifungal evaluation on the molecules, once purified, would be required to confirm this activity.

A significative group of the tentatively dereplicated active compounds were detected in single strains (62/92) exhibiting strain-specific production. In this group, the antifungal compound AS2077715 described with activity against Trichophyton species43, showed additional activity against B. cinerea in the HPLC fraction where it was contained as pure compound. The family of aspochalasins related compounds, a subgroup within cytochalasins, confirmed their antifungal activity12,44,45 in this work by inhibiting B. cinerea and M. grisea. Finally, the resorcylic acid lactone L-783277, a potent and specific inhibitor of MAP kinase46 could be correlated with the antifungal activity of Neoconiothyrium sp. CF-164281 against B. cinerea and M. grisea, given the recent report of protein kinase inhibitors as possible fungicides against fungal phytopathogens47.

The dereplication analyses facilitated the selection of hits with potential production of new antifungal compounds. These extracts included 104 hits on M. grisea, 27 on B. cinerea, 3 on C. acutatum and only 1 against F. proliferatum. This last hit against F. proliferatum, was produced by the strain Alfoldia sp. CF-168984, a potential undescribed new species within the genus Alfoldia, that was the unique hit against this phytopathogen with no known bioactive molecules detected. However, its subsequent bio-guided fractionation from larger cultivation in flasks, allowed the identification of gliovictin and hyalodendrin, both compounds belonging to the class of epidithiodioxopiperazines, that have been described in literature as broad-spectrum antimicrobial and cytotoxic agents41,42,48,49, what support its observed antifungal profile.

Screening populations of identified hits were studied to evaluate the effect of culture based approaches on the induction of antifungal activities. Solid-state fungal fermentations in rice-based media had been previously reported to provide more complex metabolite profiles than submerged fermentations in liquid media22,23,26. This correlates in our study with higher number of active extracts obtained in BRFT medium against B. cinerea and C. acutatum, being these results independent of the fatty acids identified. However, this correlation is not observed in active extracts against F. proliferatum and M. grisea, where the most productive media for antifungal activity production were LSFM and SMK-II respectively, both liquid submerged culture-based approaches.

Regarding the nutritional arrays studied, changes observed in the active metabolites production correlated for most of the strains with changes in the media formulation. Nevertheless, the high diversity of the selected fungal population made it challenging to identify any single medium as optimal. For example, the LC-HRMS profiles of the strain Chalara sp. CF-164331 showed a differential production of two related potentially new molecules (C13H13ClO6 and C13H13ClO5), tentatively responsible of the antifungal activity in LSFM, SMK-II and BRFT fermentations. This production was enhanced by the presence of SAHA, that was also reflected on the increased inhibition of M. grisea (Fig. 8). In addition, this strain selectively produced the possible mycotoxin emestrin only in the SMK-II medium, confirming previously described biosynthetic potential of species of Chalara spp50.

Fermentations in MCKX and YES media also provided interesting active extracts, with increased production levels of specific compounds. In general, all culture media included in the nutritional array approach contributed to some extent to the diversity of antifungals observed. Nevertheless, the media BRFT, LSFM and SMK-II were identified as the most productive culture conditions to ensure antifungal broad spectrum activities against the four pathogens of the panel. Confirming the effect of the variations in carbon and nitrogen sources in the induction of certain metabolites and emphasizing the highly dependence of antifungal metabolite biosynthesis on nutritional productions conditions22,23,24,25,26,51.

Furthermore, the addition of the epigenetic modifier SAHA during the fermentations promoted also significant changes in the inhibition of certain phytopathogens. The strain Pseudocoleophoma sp. CF-164448 only produced the antifungal compound 7-chloro-6-methoxymellein38, with activity against M. grisea, in LSFM with SAHA; The potential new species of Coniothyrium CF-164471 is an example of this induction with two bioactive compounds against B. cinerea (pleosporin A and Sch-218157), that were only produced in the presence of SAHA. Similarly, Anthosthomelloides leucospermi CF-166110 showed clear enhancements of production levels of possible cytochalasins, with increased inhibition rates of M. grisea; Finally, another interesting example was the strain Wojnowiciella dactylidis CF-164445 grown in BRFT medium, where, despite several known compounds were tentatively identified, the cytotoxic agent nomofungin was only produced after addition of SAHA what could explain its specific activity against B. cinerea and HepG252; On the contrary, the strain Acrostalagmus luteoalbus CF-164257 only produced the bioactive molecule exophillic acid53 when cultured without SAHA.

Despite the lack of a universal optimal fermentation condition that ensures the expression of all the biosynthetic potential of fungi, SAHA addition to a specific formulation medium was shown to modulate the expression of silent pathways, leading to enhance fungal metabolite production8,22,27,28,29. In general, most of the active known compounds were present independently of the addition of SAHA, but still, additional production of the bioactive metabolites could be observed for most of the cases in its presence inducing quantities to reveal their antifungal potential. Moreover, the obtained results indicate that the addition of SAHA during fungal fermentations significantly influences the bioactivity rates, improving the overall hit-rates against B. cinerea and M. grisea. Therefore, the most relevant effect induced by SAHA was to improve the production of a variety of antifungal metabolites typically produced in minimal quantities under non-supplemented conditions, in which their biological activity remained underestimated. This enhancement was not only observed in individual strains, but also across most of the taxonomically diverse leaf litter fungi studied. Hence, the epigenetic manipulation using SAHA represents a suitable method to generate diverse libraries for the discovery of new bioactive metabolites. Nevertheless, the opposite effects observed for C. acutatum and F. proliferatum screenings highlighted the variability in these responses of fungi to SAHA for the induction of antifungals, indicating that its impact on the metabolomic profile are strain specific and target dependent.

A relevant proof of concept of the whole approach was the production of the new antifungal agent libertamide (C16H27NO2) by the strain Libertasomyces aloeticus CF-168990. The addition of SAHA to BRFT medium specifically increased by two-fold the production levels of this molecule. Libertasomyces spp. is a genus described by Crous in 2016 from samples collected in the west coast of Cape Town in South Africa, that involves four species L. aloeticus, L. myopori, L. platani and L. quercus54,55,56,57. Our strain L. aloeticus CF-168990, isolated from leaf litter of the coastal fynbos Diosma subulate, shows 99.31% of similarity with ITS sequences of the holotype CBS 145558, isolated from leaves of Aloe also collected in South Africa57. To date, the family of libertalides A-N had been the only bioactive molecules described from Libertasomyces spp., with immunomodulatory activity58,59. Libertamide is structurally different from libertalides, as well as in its biological activity herein characterized as antifungal agent. The novel libertamide was initially identified as inhibitor of B. cinerea with IC50 in the range of 34.05 and 49.74 µg/mL (from absorbance- and fluorescence-based assays, respectively), but also shows cytotoxicity on HepG2 human cell line with very close ED50 cytotoxicity values (Table 3). However, a significant difference was obtained when the molecule was tested against Zymoseptoria tritici, with IC50 28 times lower than ED50 for HepG2 (Table 3 and Figures S16-S17). These results support the potential use of the strain Libertasomyces aloeticus CF-168990 and the novel compound libertamide as a biocontrol agent of the septoria leave blotch caused by Z. tritici. In addition, further cytotoxicity characterization of the libertamide will be performed to determine its specific bioactive profile.

Materials and methods

Fungal strain characterization

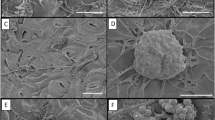

Fungal strains were previously characterized by their morphological structures developed on different agar media (YM, CMA, OAT). Subsequently, genomic DNA extraction, PCR amplification and DNA sequencing were performed in this work as previously described by Gonzalez-Menendez et al., in 201760. rDNA sequences of the complete ITS1-5.8 S-ITS2-28 S region or independent ITS and partial 28 S were compared with sequences at GenBank®, the NITE Biological Resource Center (http://www.nbrc.nite.go.jp) and CBS strain database (http://www.westerdijkinstitute.nl) by using the BLAST® application. ITS sequences that showed similarity higher than 98% were considered within the same genera and higher than 99% within the same species. However, when similarity between ITS sequences were lower than 95%, the corresponding strains were classified as potential new species.

Moreover, Maximum Likelihood method (ML) was applied with the partial sequences of 28 S gen and ultrafast bootstrap support values for phylogenetic trees were assessed calculating 1,000 replicates with IQ-TREE software61,62.

Bioactivity evaluation

The antifungal activity of the previously described OSMAC library of 2,362 fungal extracts by Serrano et al., in 202122, was characterized here against four relevant phytopathogenic fungal strains: Botrytis cinerea B05.10, Colletotrichum acutatum CF-137177, Fusarium proliferatum CBS 115.97 and Magnaporthe grisea CF-105765 using the recently described HTS Platform30. Absorbance and fluorescence raw data were used to calculate biological activity via the Genedata Screener® software (Genedata AG, Basel, Switzerland). Additional statistical analyses using JMP® software version 18 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2025, https://www.jmp.com) were applied to distribute and categorize the activity populations.

The described HTS liquid methodology was also applied with different fungal phytopathogens such as Fusarium oxysporum sbsp. cubense CBS 102025, Verticillium dahliae CBS 717.96 and Zymoseptoria tritici CBS 115943, in order to characterize the antifungal activity of the new compound libertamide. Moreover, cytotoxicity of the compound was evaluated against the HepG2 cell line (hepatocellular carcinoma, ATCC HB8065) by a MTT reduction colorimetric assay63.

Chemical dereplication of bioactive extracts

The active extracts were analyzed by High Resolution Liquid Chromatography coupled to Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) for an automated identification of known secondary metabolites by full mass spectrometry fingerprint, UV-visible profile and retention time matching with our internal proprietary database of purified and confirmed by NMR standards64. In addition, molecular formulae of compounds not directly identified in our databases were determined and manually searched against the commercial Chapman & Hall Dictionary of Natural Products (CRC Press “USB ver.30.2”) and the Natural Products Atlas database conceding their UV-visible profile and the taxonomical classification of the producer strains65,66. Finally, confirmation by tandem mass spectrometry, LC-ESI-HRMS/MS fragmentation was performed for specific cases.

Isolation of bioactive compounds

Antifungal extracts of interest were selected for scaled-up growth fermentations to obtain higher amounts of material to perform bioassay-guided purification processes61. Active fungal strains were cultivated under the same fermentation conditions where they showed antifungal activity scaling-up in two flasks containing 100 mL of the specific medium in presence and absence of SAHA (100 µM) and two EPA vials with 10 mL to replicate the original fermentation conditions. Fermentations were extracted with equal volumes of acetone or methyl-ethyl-ketone (MEK) (depending on the fermentation medium and original sample preparation) under continuous shaking at 220 rpm for 1 h. The mycelium was then pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant (400 mL) was concentrated under a stream of nitrogen.

Preparative reverse phase HPLC fractionations (Agilent™ Zorbax® SB-C8, 22 × 250 mm, 7 μm; 20 mL/min, UV detection at 210 nm) were performed to purify the compounds with a linear gradient of acetonitrile in water without TFA from 5 to 100% over 37 min. LC-HRMS and NMR spectroscopy were employed in purity confirmation over 90% and structure elucidation of purified compounds.

Conclusions

In summary, this study represents the first large systematic exploration of a large community of leaf litter associated fungi for the discovery of novel antifungal compounds to control fungal plant pathogens. Fungal isolates from leaf litter proved to be a valuable source of potential undescribed species with great biosynthetic capability. The OSMAC approach including nutritional arrays and the epigenetic elicitor SAHA, previously described to activate this metabolomic potential, has been confirmed in this work to produce numerous bioactive molecules. Every medium formulation included in the OSMAC study contributed with a high number of unique hits, resulting optimal for the discovery of antifungal compounds. The addition of SAHA to fungal fermentations clearly influenced the general diversity and quantity of metabolite production, that have a relevant impact on the overall antifungal hit-rates against specific phytopathogens. Therefore, it is difficult to propose a single fermentation condition as optimal to exploit the fungal biosynthetic potential of leaf litter. Nevertheless, the combination of both culture-based approaches has proven to be an effective strategy for the discovery of new bioactive molecules.

Furthermore, we have reported herein the novel molecule libertamide (C16H27NO2), the first secondary metabolite isolated from Libertasomyces aloeticus CF-168,990 with antifungal properties to inhibit fungal phytopathogens, specifically Z. tritici. This molecule was produced with and without SAHA, but the activity was only produced in detected quantity in the presence of the elicitor, being a clear example of the relevance of optimizing fermentation conditions to maximize chemical production. Finally, further scale-up and bioassay-guided purification studies will be required to fully characterize the potential of other new antifungals with potential valuable applications in the field as fungicides also identified in the population of hits of this study.

Data availability

Data generated and analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supplementary information files.

References

Jayawardena, R. S. et al. What is a species in fungal plant pathogens? Fungal Divers. 109, 239–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-021-00484-8 (2021).

Pandit, M. A. et al. Major biological control strategies for plant pathogens. Pathogens 11, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11020273 (2022).

De Silva, N. I., Brooks, S., Lumyong, S. & Hyde, K. D. Use of endophytes as biocontrol agents. Fungal Biol. Rev. 33, 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbr.2018.10.001 (2019).

Dean, R. et al. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 13, 414–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1364-3703.2011.00783.X (2012).

Atanasov, A. G. et al. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 200–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z (2021).

Riedling, O., Walker, A. S. & Rokas, A. Predicting fungal secondary metabolite activity from biosynthetic gene cluster data using machine learning. Microbiol. Spectr. 12 https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.03400-23 (2024).

Santra, H. K. & Banerjee, D. Natural products as fungicide and their role in crop protection in Natural Bioactive Products in Sustainable Agriculture (eds Singh, J. & Yadav, A.) 131–219 (Springer Singapore, (2020).

Xue, M. et al. Recent advances in search of bioactive secondary metabolites from fungi triggered by chemical epigenetic modifiers. J. Fungi. 9, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9020172 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Isolation and identification of an endophytic fungus of Polygonatum Cyrtonema and its antifungal metabolites. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao. 50, 1036–1043 (2010).

Park, J. H. et al. Griseofulvin from Xylaria sp. strain f0010, an endophytic fungus of Abies holophylla and its antifungal activity against plant pathogenic fungi. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 15, 112–117 (2005).

Lu, H., Zou, W. X., Meng, J. C., Hu, J. & Tan, R. X. New bioactive metabolites produced by Colletotrichum sp., an endophytic fungus in Artemisia annua. Plant Sci. 151, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00199-5 (2000).

Jing, F., Yang, Z., Hai Feng, L. & Yong Hao, Y. Jian hua, G. Antifungal metabolites from Phomopsis sp. By254, an endophytic fungus in Gossypium hirsutum. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 5, 1231–1236. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR11.272 (2011).

Anke, T., Oberwinkler, F., Steglich, W. & Schramm, G. The strobilurins - New antifungal antibiotics from the basidiomycete Strobilurus Tenacellus. J. Antibiot. 30, 806–810. https://doi.org/10.7164/antibiotics.30.806 (1977).

Niego, A. G. T. et al. The contribution of fungi to the global economy. Fungal Divers. 121, 95–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-023-00520-9 (2023).

Bills, G. F. & Gloer, J. B. Biologically active secondary metabolites from the fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 4 https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0009-2016 (2016).

Voříšková, J. & Baldrian, P. Fungal community on decomposing leaf litter undergoes rapid successional changes. ISME J. 7, 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.116 (2013).

Foster, R., Hartikainen, H., Hall, A. & Bass, D. Diversity and phylogeny of novel cord-forming fungi from Borneo. Microorganisms 10, 239; (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10020239

Grossman, J. J., Cavender-Bares, J. & Hobbie, S. E. Functional diversity of leaf litter mixtures slows decomposition of labile but not recalcitrant carbon over two years. Ecol. Monogr. 90 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1407 (2020).

Crous, P. W. et al. How many species of fungi are there at the tip of africa?? Stud. Mycol. 55, 13–33. https://doi.org/10.3114/sim.55.1.13 (2006).

Goldblatt, P. & Manning, J. Cape Plants: A Conspectus of the Cape Flora of South Africavol. 9 (National Botanical Institute, 2000).

Mamathaba, M. P., Yessoufou, K. & Moteetee, A. What does it take to further our knowledge of plant diversity in the megadiverse South africa?? Diversity 14, 748. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14090748 (2022).

Serrano, R. et al. Metabolomic analysis of the chemical diversity of South Africa leaf litter fungal species using an epigenetic culture-based approach. Molecules 26, 4262. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26144262 (2021).

Wei, Q. et al. Genome mining combined metabolic shunting and OSMAC strategy of an endophytic fungus leads to the production of diverse natural products. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 11, 572–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.07.020 (2021).

Abdelwahab, M. F. et al. Induced secondary metabolites from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus versicolor through bacterial co-culture and OSMAC approaches. Tetrahedron Lett. 59, 2647–2652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.05.067 (2018).

Gakuubi, M. M. et al. Enhancing the discovery of bioactive secondary metabolites from fungal endophytes using chemical elicitation and variation of fermentation media. Front. Microbiol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.898976 (2022).

Song, Z. et al. Secondary metabolites from the endophytic fungi Fusarium decemcellulare F25 and their antifungal activities. Front. Microbiol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1127971 (2023).

Henrikson, J. C., Hoover, A. R., Joyner, P. M. & Cichewicz, R. H. A chemical epigenetics approach for engineering the in situ biosynthesis of a cryptic natural product from Aspergillus Niger. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 435–438. https://doi.org/10.1039/B819208A (2009).

Pillay, L. C., Nekati, L., Makhwitine, P. J. & Ndlovu, S. I. Epigenetic activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters in endophytic fungi using small molecular modifiers. Front. Microbiol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.815008 (2022).

Gupta, S., Kulkarni, M. G., White, J. F. & Van Staden, J. Epigenetic-based developments in the field of plant endophytic fungi. South. Afr. J. Bot. 134, 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2020.07.019 (2020).

Serrano, R., González-Menéndez, V., Tormo, J. R. & Genilloud, O. Development and validation of a HTS platform for the discovery of new antifungal agents against four relevant fungal phytopathogens. J. Fungi. 9, 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9090883 (2023).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 346, 1256688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1256688 (2014).

Walters, D., Raynor, L., Mitchell, A., Walker, R. & Walker, K. Antifungal activities of four fatty acids against plant pathogenic fungi. Mycopathologia 157, 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MYCO.0000012222.68156.2c (2004).

Kusumah, D. et al. Linoleic acid, α-linolenic acid, and monolinolenins as antibacterial substances in the heat-processed soybean fermented with Rhizopus oligosporus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 84, 1285–1290. https://doi.org/10.1080/09168451.2020.1731299 (2020).

Cai, Y. S., Guo, Y. W. & Krohn, K. Structure, bioactivities, biosynthetic relationships and chemical synthesis of the spirodioxynaphthalenes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 1840. https://doi.org/10.1039/c0np00031k (2010).

Barash, I. et al. Crystallization and x-ray analysis of stemphyloxin I, a phytotoxin from Stemphylium botryosum. Science 220, 1065–1066. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.220.4601.1065 (1983).

Zheng, L., Lv, R., Huang, J., Jiang, D. & Hsiang, T. Isolation, purification, and biological activity of a phytotoxin produced by Stemphylium Solani. Plant Dis. 94, 1231–1237. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-03-10-0183 (2010).

Holler, U., Konig, G. M. & Wright, A. D. Three new metabolites from marine-derived fungi of the genera Coniothyrium and Microsphaeropsis. J. Nat. Prod. 62, 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1021/np980341e (1999).

Reveglia, P., Masi, M. & Evidente, A. Melleins—Intriguing Nat. Compd. Biomolecules 10, 772 ; doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10050772 (2020).

Kluepfel, D. et al. Myriocin, a new antifungal antibiotic from Myriococcum albomyces. J. Antibiot. 25, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.7164/antibiotics.25.109 (1972).

Rojas, I. S., Lotina-Hennsen, B. & Mata, R. Effect of lichen metabolites on thylakoid electron transport and photophosphorylation in isolated spinach chloroplasts. J. Nat. Prod. 63, 1396–1399. https://doi.org/10.1021/np0001326 (2000).

Strunz, G. M., Kakushima, M., Stillwell, M. A. & Heissner, C. J. Hyalodendrin: a new fungitoxic Epidithiodioxopiperazine produced by a Hyalodendron species. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 2600. https://doi.org/10.1039/p19730002600 (1973).

Stillwell, M. A., Magasi, L. P. & Strunz, G. M. Production, isolation, and antimicrobial activity of hyalodendrin, a new antibiotic produced by a species of Hyalodendron. Can. J. Microbiol. 20, 759–764. https://doi.org/10.1139/m74-116 (1974).

Ohsumi, K., Masaki, T., Takase, S., Watanabe, M. & Fujie, A. AS2077715: a novel antifungal antibiotic produced by Capnodium sp. 339855. J. Antibiot. 67, 707–711. https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2014.69 (2014).

Fang, F. et al. Two new components of the aspochalasins produced by Aspergillus Sp. J. Antibiot. 50, 919–925 (1997).

Li, X. et al. Aspochalazine A, a novel polycyclic Aspochalasin from the fungus Aspergillus sp. Z4. Tetrahedron Lett. 58, 2405–2408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.04.071 (2017).

Zhao, A. et al. Resorcylic acid lactones: naturally occurring potent and selective inhibitors of MEK. J. Antibiot. 52, 1086–1094 (1999).

Ma, Y., Liang, S., Zhang, Y., Yang, D. & Wang, R. Development of anti-fungal pesticides from protein kinase inhibitor-based anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 148 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.02.040 (2018).

Müllbacher, A. & Eichner, R. D. Immunosuppression in vitro by a metabolite of a human pathogenic fungus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 81, 3835–3837; (1984). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.81.12.3835

Rightsel, W. A. et al. Antiviral activity of gliotoxin and gliotoxin acetate. Nature 204, 1333–1334. https://doi.org/10.1038/2041333b0 (1964).

Adpressa, D. A., Stalheim, K. J., Proteau, P. J. & Loesgen, S. Unexpected biotransformation of the HDAC inhibitor Vorinostat yields aniline-containing fungal metabolites. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 1842–1847. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.7b00268 (2017).

González-Menéndez, V. et al. Assessing the effects of adsorptive polymeric resin additions on fungal secondary metabolite chemical diversity. Mycology 5, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501203.2014.942406 (2014).

Ratnayake, A. S., Yoshida, W. Y., Mooberry, S. L. & Hemscheidt, T. K. Nomofungin: a new microfilament disrupting agent. J. Org. Chem. 28, 8717–8721. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo010335e (2001).

Mori, M. et al. Identification of natural inhibitors of Entamoeba histolytica cysteine synthase from microbial secondary metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 6 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00962 (2015).

Crous, P. W. et al. Fungal planet description sheets: 400–468. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 36, 316–458. https://doi.org/10.3767/003158516X692185 (2016).

Crous, P. W. et al. Fungal planet description sheets: 469–557. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 37, 218–403. https://doi.org/10.3767/003158516X694499 (2016).

Crous, P. W. & Groenewald, J. Z. The genera of Fungi — G 4: Camarosporium and Dothiora. IMA Fungus. 8, 131–152. https://doi.org/10.5598/imafungus.2017.08.01.10 (2017).

Crous, P. W. et al. Fungal planet description sheets: 868–950. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 42, 291–473. https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2019.42.11 (2019).

Sun, Y. Z. et al. Immunomodulatory polyketides from a Phoma-like fungus isolated from a soft coral. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 2930–2940. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00463 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Secondary metabolites from coral-associated fungi: source, chemistry and bioactivities. J. Fungi. 8, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof8101043 (2022).

González-Menéndez, V. et al. Biodiversity and chemotaxonomy of Preussia isolates from the Iberian Peninsula. Mycol. Prog. 16, 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-017-1305-1 (2017).

González-Menéndez, V. et al. Fungal endophytes from arid areas of andalusia: high potential sources for antifungal and antitumoral agents. Sci. Rep. 8, 9729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28192-5 (2018).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300 (2015).

Mackenzie, T. A. et al. Acoustic droplet ejection facilitates cell-based high-throughput screenings using natural products. SLAS Technol. 29, 100111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slast.2023.10.003 (2024).

Pérez-Victoria, I., Martín, J., Reyes, F. & Combined LC/UV/MS and NMR strategies for the dereplication of marine natural products. Planta Med. 82, 857–871. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-101763 (2016).

Pérez-Victoria, I. Natural Products Dereplication: databases and analytical methods in Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products 124 (eds. Kinghorn, A. D., Falk, H., Gibbons, S., Asakawa, Y., Liu, J. K., Dirsch, V. M.) 1–56Springer, Cham, (2024).

van Santen, J. A. et al. The natural products atlas 2.0: a database of microbially-derived natural products. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D1317–D1323. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab941 (2022).

Tsuda, M. et al. Scalusamides A-C, new pyrrolidine alkaloids from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium citrinum. J. Nat. Prod. 68, 273–276. https://doi.org/10.1021/np049661q (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out by R.S. as part of the Ph.D. Program ‘New Therapeutic Targets: Discovery and Development of New Antibiotics’ from the School of Master’s Degrees of the University of Granada, Spain. This study was funded by Fundación MEDINA, Centro de Excelencia en Medicamentos Innovadores en Andalucía, Granada, Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S., V.G.-M., J.R.T and O.G. designed the experiments; R.S., C.T. and V.G.-M. cultured and identified the fungal strains; R.S., I.S. J.M., I.P.-V. and J.R.T performed the purification and identification of compounds; R.S. and T.A.M. screened the extract library and compounds; R.S., V.G.-M., J.M., I.P.-V, and J.R.T. collected and analyzed the data; R.S. wrote the main manuscript text; V.G.-M., J.R.T. and O.G critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Serrano, R., González-Menéndez, V., Pérez-Victoria, I. et al. Leaf litter associated fungi from South Africa to control fungal plant pathogens. Sci Rep 15, 30219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09693-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09693-6