Abstract

While observational studies suggest associations between ankle spacing width (ASW, defined as the horizontal distance between the medial malleoli under weight-bearing conditions) and osteoporosis (OP), fractures, and falls, causal evidence remains limited. This gap hinders the translation of ASW measurements into clinical risk stratification tools. This study aimed to investigate the causal relationships between ASW indicators and site-/age-specific bone mineral density (BMD), bone fracture and fall risks. Genetic exposure data for ASW indicators were retrieved from the MRC-IEU datasets, and the outcome data were all derived from the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis Consortium (GEFO). Genome-wide associations of single nucleotides polymorphisms (SNPs) were served as instrumental variables (IVs) to infer causal effects using two-sample mendelian randomization (TSMR) and multivariable mendelian randomization (MVMR) analyses. The results of sites-specific TSMR analysis revealed that per unit increase in ASW (including left and right) were causally associated with lower estimated from quantitative heel ultrasounds BMD (eBMD, reflecting calcaneal bone density) and total-body BMD (TB-BMD, assessed via DEXA scans), with pronounced effects in individuals aged over 60 years. Age-stratified analyses revealed no significant associations between ASW and TB-BMD in younger age groups (age ≤ 15, 15 < age ≤ 30, 30 < age ≤ 45, 45 < age ≤ 60) or site-specific fractures/falls. MVMR adjustment for BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption confirmed persistent causal associations between ASW and reduced eBMD and TB-BMD, particularly for TB-BMD in individuals aged over 60 years. Our study provides evidence that genetically predicted ASW is associated with reduced eBMD and TB-BMD, and a causal association between ASW and TB-BMD (aged over 60), suggesting ASW as a potential auxiliary biomarker for monitoring age-dependent bone loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a chronic systemic skeletal disorder characterized by reduced bone mineral density (BMD), microarchitectural deterioration, and increased fracture risk, imposing substantial global health burdens1. It was estimated that over 9 million fragility fractures occur worldwide in 2019 due to OP, leading to profound morbidity and socioeconomic costs2. While the BMD measurement remains the gold standard for OP diagnosis, bone mineral loss exhibits age-/site-specific decline patterns3,4. This underscores the need to identify novel biomarkers for risk stratification in this multifactorial disease.

The ankle joint, critical for mobility and postural stability, has emerged as a potential predictor of skeletal health. Ankle spacing width (ASW), defined as the horizontal distance between the medial malleoli of both ankles measured by calipers during weight-bearing standing, is a biomechanical parameter reflecting skeletal alignment5,6,7. This standardized anthropometric measurement captures the structural spacing of the tibial plafond and talus, independent of soft tissue interference. Functionally, ASW represents a static indicator of lower-limb axial loading capacity, distinct from dynamic gait parameters or musculoskeletal indicators. However, the presence of confounding factors (e.g., obesity, physical activity) and the potential for reverse causality in such studies preclude definitive conclusions about directional relationships.

Given the significant contribution of genetic factors to OP risk, Mendelian randomization (MR) provides a robust approach to infer causal relationships by leveraging genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs)8,9. This method mitigates residual confounding and reverse causation inherent in observational studies. Specifically, we applied MR to investigate putative causal effects of ASW on site-/age-specific BMD, fracture and fall risk. Understanding ASW’s causal role is clinically crucial, as it may represent a modifiable biomechanical factor influencing bone strength and fracture susceptibility, thereby informing targeted preventive interventions.

Methods

Study design

As a two-stage MR research, this study aimed to assess the causal associations of ASW on BMD, and the risk of fractures and falls. The analyses were conducted using publicly available abstract-level genome-wide association study (GWAS) datasets, which had already obtained ethical approval from their respective institutional review boards and included informed consent from participants. In order to control false positives that may arise from various factors inherent in the research process, we utilized the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method for multiple test corrections. The reporting of this study adheres to the guidelines for strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using MR (STROBE-MR) (Supplementary text 1)10,11. Figure 1 clearly illustrated our study design.

Data sources

Exposure data sources

ASW measurements were obtained from the UK Biobank (UKB) physical examination dataset (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). Trained personnel used digital calipers to measure the horizontal distance between the medial malleoli of each ankles while participants stood barefoot in a weight-bearing position12. This protocol ensures standardized skeletal alignment assessment, with detailed methodology publicly accessible in the UKB Anthropometry Documentation. Left/right ASW measurements were analyzed separately to assess anatomical specificity (Supplementary Table S1).

Outcome data sources

We selected BMD as the primary outcome to proxy OP risk, as it is a gold-standard diagnostic criterion endorsed by clinical guidelines and a well-established predictor of fracture risk. Although BMD alone cannot comprehensively reflect bone microstructure or the non-BMD determinants of fracture risk, we conducted site-specific and age-stratified BMD analyses to capture the critical pathophysiological dimensions of BMD. Additionally, these analyses were supplemented with evaluations of fracture and fall outcomes.

Due to the varied BMD among the different sites and age subgroups, the genetic summary data regarding five sites-specific BMD measures [lumbar spine BMD (LS-BMD), forearm BMD (FA-BMD), femoral neck BMD (FN-BMD), estimated from quantitative heel ultrasounds BMD (eBMD) and total body BMD (TB-BMD)] and five age-stratified groups (age ≤ 15, 15 < age ≤ 30, 30 < age ≤ 45, 45 < age ≤ 60, age > 60) were derived from the three large GWAS analyses consortiums based on the reports of Zheng et al., Kemp et al. and Medina-Gomez et al., respectively13,14,15. Among them, TB-BMD was measured by whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), reflecting systemic bone mass. FN-BMD, LS-BMD, FA-BMD were assessed by DEXA at FN, LS and FA, respectively. eBMD was estimated via quantitative ultrasound of the heel, capturing trabecular bone density. Age stratification cutoffs were selected based on established BMD trajectory phases: less 15 years (peak bone mass accretion), 15 to 30 years (peak mass maintenance), 30 to 45 years (initial bone loss onset), 45 to 60 years (continued bone loss), over 60 years (accelerated loss phase)14.

Fracture and fall data sources

Considering the close relationships of OP with fractures and falls, summary statistics for sites-specific fractures (ankle fractures, wrist fractures, arm fractures, leg fractures, spine fractures and other bone fractures) and falls were obtained from other publicly available GWAS of MRC-IEU and Trajanoska et al., respectively16. All datasets were harmonized through the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis Consortium (GEFOS) portal to ensure consistent allele alignment.

IVs selection

In MR analysis, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are served as IVs to assess the impact of modifiable exposure factors on outcomes10. Genetic instruments were selected under three MR assumptions. First, the correlation assumption requires that Genome-wide significant (P < 5 × 10− 08) SNPs associated with ASW were identified, and Linkage disequilibrium ([LD], r2 < 0.001, clumping window = 10,000 kb) was resolved using European reference panels17. Second, the independence assumption necessitated the exclusion of confounders affecting both exposure and outcomes. Given that BMI is a known modulator of bone metabolism and mechanical loading on joints, it may influence both ASW via weight-bearing effects and BMD/fracture risk through altered bone remodeling18. To mitigate this confounding pathway, we systematically screened and removed IVs associated with BMI (P < 5 × 10− 08) using PhenoScanner19. Third, it was important to ensure that the IVs only affect outcomes through exposures, without interference from other factors. To identify and exclude any levels of pleiotropy, we employed the MR pleiotropy residuals and outliers (MR-PRESSO) test20.

To assess weak IV bias, the F-statistics for each SNP were calculated separately, taking into account the limitations of IV selection. F-statistics > 10 indicated sufficient strength, and it reduced the susceptibility to weak IV bias in the results. The formula used was:

F = R2 × (N - 2) / (1 - R2),

where R2 represents the variance of exposure explained by each IV21. FDR P-values were further applied to control for type I errors in multiple testing.

Statistical analysis

TSMR analysis

In this study, we identified the inverse variance weighting method (IVW) and the weighted median method (WM) as the main methods for estimating causal associations IVW provides robust estimates when MR assumptions hold (no pleiotropy, valid instruments, and independence from confounders), whereas WM mitigates horizontal pleiotropy by requiring validity in only > 50% of IVs. To ensure rigorous validation of MR assumptions, we implemented specific diagnostic protocols: (1) Correlation/Independence Assumptions: Genetic instruments were pre-screened via PhenoScanner to remove SNPs associated with confounders. LD clumping (r² < 0.001) minimized correlated pleiotropy. (2) Exclusion Restriction (No pleiotropy): MR-Egger regression (intercept P < 0.05 indicated violation; estimates corrected via MR-PRESSO outlier removal). (3) Cochran’s Q (P < 0.05 indicated heterogeneity. (4) Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (visualized in Supplementary Fig. 1) assessed the robustness of causal estimates to individual SNP exclusion.

MVMR analysis

Smoking, alcohol consumption, and BMI were selected as covariates due to their established roles in bone metabolism and prior evidence linking them to both ASW and osteoporosis-related outcomes. While cross-sectional studies associate ankle pressure with fall risk, our null findings for fractures/falls imply that ASW-driven BMD reductions may not suffice to trigger fragility events in isolation. These covariates were prioritized based on data availability and their statistical significance in preliminary univariate analyses. MVMR analysis was implemented to determine the independent effects of ASW on BMD and the risk of fractures and falls. In the MVMR analysis, MR-PRESSO model was used to correct horizontal pleiotropy of the causal effects, estimate heterogeneity, and exclude potential outliers. P < 0.05 of MVMR analysis was denoted to be statistical significance.

Results

After removing LD, we identified 368 SNPs associated with ASW. Specifically, we found 197 SNPs associated with ASW (left) and 212 SNPs associated with ASW (right). Furthermore, our examination using PhenoScanner revealed no SNPs associated with BMI. The F-values for the IVs included in the analysis ranged from 29.78 to 676.57, indicating that the results were less susceptible to weak IV bias. Moreover, the IVs explained 10.17% of the variation in ASW, 8.10% in ASW (left), and 8.46% in ASW (right), demonstrating their interpretation degree on the exposure phenotype (Supplementary Table S2).

Causal effects of ASW on sites-specific BMD, fracture and fall risks

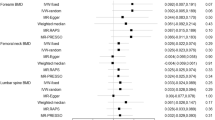

Genetically predicted ASW (including bilateral measures) demonstrated significant evidence of a causal association with reduced eBMD and TB-BMD. Specifically, per unit increase in ASW reduced eBMD by 0.281 SD (Beta: -0.281, 95% CI: -0.328, -0.234, P = 1.43 × 10− 31). Similar effects were observed for left ASW (Beta: -0.264, 95% CI: -0.321, -0.207, P = 1.69 × 10− 19) and right ASW (Beta: -0.282, 95% CI: -0.327, -0.217, P = 2.61 × 10− 22). In addition, ASW reduced TB-BMD by 0.102 SD (IVW: Beta = -0.102, 95% CI: -0.155, -0.049, P = 1.26 × 10− 04), with consistent results for left (Beta: -0.069, 95% CI: -0.126, -0.012, P = 0.016) and right ASW (Beta: -0.088, 95% CI: -0.147 to -0.029, P = 0.003) (Supplementary Table S3 & Fig. 2). The FDR P-value of all causal associations was less than 0.05. TSMR analysis revealed no causal associations between genetically (Fig. 3) predicted ASW (including bilateral measures) and risks of site-specific fractures or falls (P > 0.05). (Supplementary Table S5 & Fig. 4). Sensitivity analysis confirmed no significant pleiotropy or heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q test P > 0.05; MR-Egger intercept P > 0.05), and leave-one-out analysis showed no single SNP drove the causal estimates (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Forest plot of causal associations of ASW on sites-specific BMD with IVW method. ASW ankle spacing width, CI confidence interval, BMD bone mineral density, FA forearm, FN femoral neck, LS lumbar spine, eBMD estimated from quantitative heel ultrasounds BMD, TB-BMD total-body BMD, N. SNPs number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms, IVW inverse-variance weighted.

Causal effects of ASW on age-specific BMD

In the subgroup analysis of ASW and age-specific BMD, the study found that genetic evidence supporting a putative causal association between ASW and TB-BMD (age > 60) (Beta: -0.084, 95%CI: -0.153, -0.015, P = 0.016) (Supplementary Table S4 & Fig. 3). The FDR P-value was less than 0.05, and further sensitivity analysis confirmed this causal association. However, the suggested causal association between ASW (left) and TB-BMD (45 < age ≤ 60) did not pass the FDR test (FDR P-value = 0.050) (Fig. 5), and thus was excluded from significant associations. Furthermore, no causal associations were observed between ASW and the risk of TB-BMD in individuals aged 0 to 15, 15 to 30, and 30 to 45.

Independent associations of ASW with eBMD and TB-BMD after covariate adjustment

To explore the causative impact of ASW on risk of eBMD and TB-BMD, we conducted MVMR analysis. After controlling for BMI, smoking and drinking alcohol, the causal association persisted between ASW exposure and eBMD remained significant after correction (Beta = -0.351, 95% CI: -0.407, -0.294, P = 7.05 × 10− 34). In general, we also observed the causal association between ASW exposure and TB-BMD after correcting for BMI, smoking and drinking alcohol (Beta = -0.152, 95% CI: -0.221, -0.082, P = 1.82 × 10− 05), a significant association persisted for TB-BMD in individuals aged > 60 (Beta = -0.142, 95% CI: -0.241, -0.042, P = 1.82 × 10− 05) (Fig. 6 & Supplementary Table S6).

Discussion

OP, a systemic skeletal disorder marked by compromised bone strength and elevated fracture risk, poses a critical public health challenge, particularly in aging populations22. Our MR analysis suggests a potential causal role of ASW on reduced estimated and TB-BMD, with amplified impacts observed in individuals aged over 60, which supports ASW as a clinically meaningful predictor for age-dependent bone loss. Notably, these associations remained robust after adjusting for BMI, smoking, and alcohol use, establishing ASW as an independent biomarker of OP susceptibility. Notably, while ASW demonstrated causal effects on reduced BMD, no significant associations were found with site-specific fractures or falls. This difference may arise from two interrelated factors. First, ASW primarily reflects static skeletal alignment under weight-bearing conditions, whereas fractures and falls are dynamic events influenced by complex neuromuscular coordination, reaction time, and environmental hazards—factors not captured by ASW measurements. Second, although BMD reduction is a well-established fracture risk factor, the magnitude of BMD declines causally linked to ASW in our study may be insufficient to independently trigger fragility fractures without concurrent deterioration in bone microarchitecture or trauma mechanisms7. This aligns with prior evidence that fracture prediction requires integration of BMD with clinical risk factors (e.g., prior falls, family history), suggesting ASW’s utility may lie primarily in early BMD risk stratification rather than direct fracture prognostication16.

ASW, which directly quantifies inter-malleolar distance under weight-bearing conditions, as a biomechanical proxy for skeletal alignment. Functionally, ASW reflects static axial loading capacity, distinct from dynamic gait parameters previously linked to falls (e.g., ankle pressure in older adults or joint morphology in OA23,24. Critically, our MR analysis extends beyond these correlative observations by establishing ASW as a causal determinant of systemic BMD reduction, particularly in the elderly. The age-stratified results align with the biology of skeletal aging. The pronounced ASW-BMD association in over 60-year-olds reflects accelerated bone loss during this phase, where hormonal decline, sarcopenia, and cumulative mechanical stress synergistically exacerbate resorption25. These functional insights align with our age-stratified results showing amplified ASW effects over 60-year-olds, where cumulative mechanical stress synergizes with hormonal decline to accelerate bone resorption25. This positions ASW as a feasible, imaging-free biomarker for age-dependent bone loss screening in high-risk elderly populations.

To our knowledge, this is the first MR study establishing genetic causality between ASW and OP-related outcomes, avoiding reverse causation in prior studies. By stratifying TB-BMD analyses across age groups, we further disentangle ASW’s role in lifelong bone homeostasis. Clinically, ASW’s association with heel ultrasound-based eBMD and systemic TB-BMD highlights its dual utility: eBMD for community screening, TB-BMD for comprehensive assessment. As ASW showed causal effects on BMD but not fractures/falls, its clinical utility may primarily lie in bone loss risk stratification rather than direct fracture prediction. Integrating ASW into geriatric screening for BMD monitoring could enhance early identification of high-risk individuals, particularly when combined with established tools like eBMD or DEXA. A cost-effectiveness analysis of such a combined approach could further justify its adoption in resource-limited communities. However, population-specific ASW reference ranges must first be established through epidemiological studies, as current data are derived from European cohorts. Age-specific BMD trajectories exhibit distinct biological patterns: adolescence (less 15 years) marks peak bone mass acquisition, young adulthood (15 to 30 years) sustains peak mass, midlife (30 to 45 years) initiates gradual loss, and late adulthood (over 60 years) accelerates loss due to hormonal shifts and reduced osteoblast activity. These critical transitions, particularly the accelerated decline in over 60 years driven by estrogen deficiency in women and sarcopenia in both sexes, justify our age stratification25. Future research should validate these findings in multi-ethnic cohorts and explore whether ASW-targeted interventions (e.g., gait training or mechanical loading exercises) mitigate age-related BMD decline.

Although MR reduces confounding, the term “causal” here reflects inferred relationships under MR assumptions, not deterministic causation. Several limitations warrant consideration. First, European-centric genetic data limit generalizability to diverse ancestries. Second, the selected SNPs explained only a small proportion of the exposure variance. Unidentified or uncharacterized SNPs associated with the exposure could potentially influence the causal estimates. Third, while our MVMR analysis adjusted for BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption, residual confounding from unmeasured factors (e.g., physical activity, dietary calcium intake, or hormonal status) cannot be entirely ruled out. These factors may influence both ASW and BMD through distinct biological pathways (e.g., mechanical loading modulation by physical activity, direct effects of calcium on mineralization). The omission of these variables was primarily due to limitations in harmonized genetic datasets; future studies incorporating genetic instruments for these specific covariates are warranted to elucidate their potential mediating or confounding roles and refine the causal estimates of primary exposures.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that genetically predicted ASW provides significant evidence of causal effects on reduced eBMD and TB-BMD, with heightened impact in individuals aged over 60 years. These associations remain robust after adjustment for BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption, suggesting that ASW may serve as an auxiliary predictive tool for age-dependent bone loss, requiring further validation with imaging/clinical indices. Although no causal links were found between ASW and fracture/fall risks, our findings support that ASW may serve as an auxiliary predictor for age-related bone loss.

Data availability

The data and material that support the findings of this study are available from public datasets that could be found in NHGRIEBI GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/).

References

Wu, Y. et al. Extracellular derivatives for bone metabolism. J. Adv. Res. S2090-1232 (24). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.01.011 (2024).

Dong, Y. et al. What was the epidemiology and global burden of disease of hip fractures from 1990 to 2019? Results from and additional analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 481, 1209–1220 (2023).

Wang, H. S. et al. Mind gaps and bone snaps: exploring the connection between alzheimer’s disease and osteoporosis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-023-00851-1 (2024).

Nethander, M. et al. BMD-Related genetic risk scores predict Site-Specific fractures as well as trabecular and cortical bone microstructure. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, e1344–1357 (2020).

Balzini, L. et al. Clinical characteristics of flexed posture in elderly women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 51, 1419–1426 (2003).

Mohebi, S., Torkaman, G., Bahrami, F. & Darbani, M. Postural instability and position of the center of pressure into the base of support in postmenopausal osteoporotic and nonosteoporotic women with and without hyperkyphosis. Arch. Osteoporos. 14, 58 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Quantitative CT-Based methods for bone microstructural measures and their relationships with vertebral fractures in a pilot study on smokers. JBMR Plus. 5, e10484 (2021).

Sekula, P., Del Greco, M., Pattaro, F., Köttgen, A. & C. & Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 3253–3265 (2016).

Ference, B. A., Holmes, M. V. & Smith, G. D. Using Mendelian randomization to improve the design of randomized trials. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med. 11, a040980 (2021).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. JAMA 326, 1614–1621 (2021).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomisation (STROBE-MR): explanation and elaboration. BMJ 375, n2233 (2021).

Lyon, M. S. et al. The variant call format provides efficient and robust storage of GWAS summary statistics. Genome Biol. 22, 32 (2021).

Kemp, J. P. et al. Identification of 153 new loci associated with heel bone mineral density and functional involvement of GPC6 in osteoporosis. Nat. Genet. 49, 1468–1475 (2017).

Medina-Gomez, C. et al. Life-Course Genome-wide association study Meta-analysis of total body BMD and assessment of Age-Specific effects. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102, 88–102 (2018).

Zheng, H. F. et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies EN1 as a determinant of bone density and fracture. Nature 526, 112–117 (2015).

Gregson, C. L. et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch. Osteoporos. 17, 58 (2022).

Brion, M. J. A., Shakhbazov, K. & Visscher, P. M. Calculating statistical power in Mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 1497–1501 (2013).

Lin, Y. J. et al. Genetic predisposition to bone mineral density and their health conditions in East Asians. J. Bone Min. Res. 39, 929–941 (2024).

Ding, P., VanderWeele, T. J. & Robins, J. M. Instrumental variables as bias amplifiers with general outcome and confounding. Biometrika 104, 291–302 (2017).

Border, R. et al. Assortative mating biases marker-based heritability estimators. Nat. Commun. 13, 660 (2022).

Burgess, S., Thompson, S. G. & CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 755–764 (2011).

Zhou, M., An, Y. Z., Guo, Q., Zhou, H. Y. & Luo, X. H. Energy homeostasis in the bone. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. S1043-2760 (23), 00277–00271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2023.12.009 (2024).

Chung, C. M., Shin, S., Lee, Y. & Lee, D. Y. Determination of the predictors with the greatest influence on walking in the elderly. Med. (Kaunas). 58, 1640 (2022).

Seki, H., Nozaki, S., Ogihara, N., Kokubo, T. & Nagura, T. Morphological features of the non-affected side of the hindfoot in patients with unilateral varus ankle osteoarthritis. Ann. Anat. 252, 152198 (2023).

Reid, I. R. & McClung, M. R. Osteopenia: a key target for fracture prevention. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 12, 856–864 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by Deyang Science and Technology Program (2024SZY060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

For research articles with several authors, the following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.D.; methodology, H.L.; software, J.M.; validation, X.X. and Y.D. and H.L.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, Y.D.; supervision, B.Q.; project administration, B.Q.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, XP., Dai, YJ., Li, HX. et al. Causal Association Between Genetically Predicted Ankle Spacing Width and Risk of Age-Related Bone Mineral Density. Sci Rep 15, 24863 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09765-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09765-7