Abstract

Evidence shows enhanced walking environment promotes overall physical activities and further alleviates the risk of chronic diseases and mental disorders. Current walkability research is limited by traditional GIS methods that fail to capture micro-level details and human perceptions. Additionally, existing image segmentation techniques return low accuracy when extracting complex street environment features. Therefore, we developed a hierarchical evaluation framework for urban walkability with high precision image segmentation techniques, and subjective measurements on four first-level indicators (greenness, openness, crowding, safety) and their corresponding second-level indicators. An entropy weight method was constructed to quantify the indicators based on questionnaires from 120 volunteers. Furthermore, we developed Detail-Strengthened High-Resolution Network (DS-HRNet), a deep learning model that demonstrates a 15% improvement in street scene segmentation performance compared to existing models. Using the newly developed deep learning model, we analyzed 113,900 street view images in central Wuhan City, China. Our walkability results revealed spatial heterogeneity across the city, characterized by substantial disparities between adjacent areas, particularly in commercial areas. Subsequent socioeconomic analysis demonstrated that better walkability exists in areas of higher socioeconomic status but lower proportion of non-local residents. This walkability inequality may further lead to health disparities through its influence on physical activity and social interaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The walkability index quantifies the pedestrian friendliness of an area, incorporating factors such as safety, accessibility, and environmental quality1. Recent studies have demonstrated the association between walkability and health benefits. For example, one study reported walkable environments motivate residents to engage in outdoor physical activities, thereby reducing the risk of chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension2,3. Furthermore, walkability can contribute to mental well-being through enhanced social interactions, leading to reduced rates of anxiety and depression4. This positive effect is particularly evident among older adults. Studies show that older adults who engage in more outdoor physical activities tend to feel less depressed compared to those who are less active outdoors5.

The relationship between walkability and health outcomes is supported by several theoretical frameworks. Environmental Perception Theory suggests that natural visibility and environmental comfort directly contribute to stress reduction and enhanced physical-mental health outcomes6,7,8. Environmental Stress Theory demonstrates that high density and restricted environments increase psychological stress by elevating environmental load9,10. Additionally, the Social-Ecological Model demonstrates the influence of physical characteristics and perceived security on human interactions and well-being in urban spaces11,12,13.

Despite evidence showing the health benefits of walkable environments, studies indicate that high-quality walking infrastructure is concentrated in high-income communities14. Low-income and marginalized communities, which already experience higher health risks than high-income communities, have limited access to high-quality walking infrastructure and health-promoting walking environments14. Given the established links between walkability and health outcomes, the disparities in walking environments may exacerbate health inequalities across urban residents. Therefore, ensuring equitable access to walkable environments serves as an integrated strategy for public health promotion.

Current research on walkability commonly employs three approaches through GIS-based spatial analysis, questionnaire surveys, and field observations. Among these approaches, GIS-based spatial analysis has been widely adopted, with its theoretical foundation tracing back to the “3D” method (i.e., Density, Diversity, and Design)15. This method indicates that walkability is influenced by higher population density, diverse land use, and pedestrian-oriented design. Building on the “3D” method, the “5D” method was introduced by adding transit distance and destination accessibility15which has been widely applied in current research16. However, GIS-based methods have clear limitations. While both the “3D” and “5D” methods effectively capture macro-level community characteristics, they struggle to evaluate micro-level details such as street facilities and sidewalk quality, mainly due to data constraints and access restrictions17. Moreover, these methods overlook perceptions from pedestrians and assume that their travel mode selections are primarily based on cost-effectiveness. Studies indicate that pedestrians often value safety and comfort beyond such practical considerations, highlighting complex behavioral preferences in walkability18.

To overcome these limitations, researchers have turned to surveys, interviews, and field observations to evaluate walkability. For example, large-scale telephone surveys with over 1,000 volunteers have been conducted to evaluate walking environments19. While in Oregon, researchers evaluated street safety for children through parent feedback about streets and intersections20. Another study also used both pilot and formal surveys to investigate pedestrian preferences for different walking environment features21. While these methods provide valuable insights about local walkability conditions and individual perceptions, they are limited by sample size and resource requirements19,21. This highlights the demand for developing integrated evaluation that combines strengths of multiple approaches while maintaining operational efficiency.

In recent years, with the advancement of computer vision technology, researchers have begun to use deep learning models to evaluate walkability scores through street view images22. Compared to traditional methods, deep learning approaches can automatically evaluate walkability through street view image analysis, reducing the data collection costs while providing consistent assessment results23. These approaches can capture multiple environmental factors that align with the theoretical frameworks, including street greenery and visual enclosure (Environmental Perception Theory)6,7,8crowding and spatial density (Environmental Stress Theory)9,10and safety features (Social-Ecological Model)11,12,13. For example, using the DeepLabV3 + model to analyze Google Street View images, researchers developed a walkability index that considers multiple environmental factors, including street greenery, visual enclosure, height-to-width ratio, obstacles, visual complexity, sidewalks, and slope23. Similarly, a study in Taipei applied the DeepLabV3 + model to evaluate walkability based on comfort, safety, greenery, and functionality features24.

However, existing models still have limitations in the image segmentation from images for walkability assessment. First, most studies rely on basic image segmentation techniques, including PSPNet, FCN-8s, SegNet, and DeepLab v3 + model22,25. These models demonstrate limited accuracy in street feature identification, often resulting in inaccurate segmentation results and misclassified features26,27. Moreover, the growing complexity of urban street environments requires high-precision semantic segmentation models for accurate feature extraction. To our knowledge, limited research has integrated high-precision models with human perception metrics for walkability assessment.

Our study developed a walkability assessment framework through three innovative approaches: (1) developing an integrated analytical framework that incorporates high-precision street view segmentation models with perception-weighted metrics; (2) establishing a survey-based walkability weight that quantifies pedestrian perceptions of streetscape features through structured questionnaires; and (3) constructing a high-precision deep learning framework for automated street feature extraction. Taking the central area of Wuhan, China as a case study, we also discussed the association between walkability and socio-demographic characteristics, highlighting spatial inequities in walking environments. Our findings highlight the critical need for creating equitable walking environments to promote public health for all residents.

Methods

Study design

In this study, we developed an innovative framework to evaluate walkability scores at the micro-scale and examine the spatial patterns of pedestrian environment quality in Wuhan, as shown in Fig. 1. First, we constructed a perception-based weighting scheme based on questionnaire responses from 120 volunteers, incorporating four first-level indicators (i.e., greenness, openness, crowdedness, and safety) and seven corresponding second-level indicators (i.e., vegetation coverage rate, sky visible ratio, space occupancy rate, traffic flow, proportion of sidewalks, road safety facilities, and parking on sidewalks). The perceived walkability weights were determined using the entropy weight method based on importance ratings of different indicators. We then constructed a high-precision deep learning model to extract semantic information from street view images. Finally, we calculated comprehensive walkability scores by combining the objective street feature proportions with their corresponding entropy weights. Taking the central area of Wuhan as a case study, we performed a Spearman’s correlation analysis to investigate the relationship between walkability and socio-demographic characteristics.

Data collection

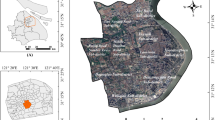

We selected seven central districts in Wuhan, China (i.e., Hanyang, Qiaokou, Jianghan, Jiangan, Wuchang, Qingshan, and Hongshan) as our study area (See Supplementary Fig. S1). We obtained the road network data from OpenStreetMap (OSM) platform in 202128. For analysis purposes, we removed non-walkable routes such as highways and tunnels to focus on pedestrian-accessible streets. Following previous studies on urban street assessment29we established sampling points at 100-meter intervals along the road network using ArcGIS Pro 3.030. At each sampling point, we captured images from four directions (0°, 90°, 180°, 270°) to ensure comprehensive coverage. A customized Python script was developed to retrieve street view images from Baidu Maps based on the geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) of each sampling point. The script accessed images through Uniform Resource Locator (URL) parameters and Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) requests to download the street view images. Supplementary Figure S2 shows the retrieved street view from four directions at one sample point. In total, we collected 113,900 street view images across Wuhan, all updated in June 2021. However, it should be noted Baidu Map does not provide publicly available street network and therefore we retrieved network data from OSM. To calculate Amap congestion index, we divided the study area into 50 m × 50 m grids using the Amap rectangular query system. Real-time traffic data was obtained through Amap Application Programming Interface (API) requests for road centerline points located within the grids, with a 50 m radius buffer zone around each point. The data collection process was conducted hourly from November 17 to 19, 2021. To ensure data reliability, we averaged the collected values and then integrated the processed traffic data with the pedestrian road network in ArcGIS 10.7. In addition, socio-demographic data were obtained from the 2021 seventh population census released by the Wuhan Municipal Government (https://www.stats.gov.cn). We retrieved multiples demographic indicators including non-local household registration rates, age structure (i.e., population aged < 14 and ≥ 60), higher education attainment (i.e., bachelor’s degree or higher), gender ratio (male-to-female ratio), and per capita room number for subsequent walkability equity analysis.

High-precision semantic segmentation model for street view images

To achieve more precise semantic segmentation of street views, we developed a new model named Detail-Strengthened High-Resolution Network (DS-HRNet), as shown in Fig. 2. The model optimized the accuracy of micro-scale street feature extraction from street view images.

High-Resolution Network (HRNet), which serves as our baseline model, has shown strong performance in semantic segmentation tasks. This model is able to retain high-resolution features while repeatedly combining features at different resolution levels throughout the network. However, when dealing with complex street scenes, HRNet has two main challenges. First, HRNet relies on standard convolution with fixed receptive fields. This fixed structure cannot effectively adapt to varying object shapes and scene changes, limiting its ability to capture contextual information. Additionally, the bilinear Interpolation adopted in HRNet for upsampling operations lead to information loss, particularly for edge and texture preservation.

To address these limitations, we propose the DS-HRNet model, which optimizes the original HRNet model by incorporating two key modules: the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module and the Multi-scale Feature Fusion (MFF) module. The ASPP module introduces parallel multi-scale feature extraction at the fourth stage output of HRNet model. It uses dilated convolutions with rates of 6, 12, and 18, combined with global average pooling. This design captures and fuses contextual information across different scales, improving multi-scale object recognition without increasing computational cost. In addition, the MFF module replaces standard convolution with deformable convolution. Its adaptive design allows the model to adjust receptive field shapes through learnable sampling positions, making it effective for irregular object features. The module is structured with four parallel branches, containing 48, 96, 192, and 384 channels, respectively. Each branch implements three 3 × 3 deformable convolution units, along with batch normalization (BN) layers and Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions to improve network non-linear expression. For feature reconstruction, the module employs branch-specific deconvolution with different upsampling rates (×1, ×2, ×4, ×8). These learnable upsampling operations improve the preservation and recovery of feature details.

We implemented DS-HRNet using Python 3.8 and PyTorch 2.1.2 on workstations equipped with dual NVIDIA GTX3090 GPUs. For model training, we selected the Cityscapes dataset, which includes street scenes from 50 cities worldwide across spring, summer, and autumn with 30 pre-defined classes31. The dataset was chosen for its annotated street view segments that align with our requirements for street-level imagery analysis. The training process utilized a Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer (base learning rate: 0.01, momentum: 0.9, weight decay: 0.0004) and focal loss as the loss function. We set the batch size to 12 and ran 120,000 training iterations. For performance evaluation, we used mean intersection over union (mIoU), a standard metric in semantic segmentation, with detailed results available in Appendix A.

Selection of perceived walkability indicators

Based on a review of relevant literature, we identified 14 micro-scale factors commonly linked to walkability23,26,32,33,34. To understand pedestrian perception, we conducted an online survey through Wenjuanxing (i.e., a survey platform similar to Qualtrics) which utilizes IP-based location verification protocols for participant geographic authentication (https://www.wjx.cn/help/help.aspx?catid=21).

To maintain spatial consistency with the study area, this analysis only included responses from participants of Wuhan, as indicated through IP-based location data (designated as “Hubei, Wuhan” in the survey). This survey aims to collect only visual perceptions on street environment during daily walking experience. All participants were voluntary respondents. They were only asked for online participation of survey questionnaires with no personal identity information collected. Each questionnaire began with an informed consent form that clearly stated the research purpose and data usage. The street environment focuses on features derived from segmentation models. For example, questions on sidewalks include width, occupancy and congestion levels. A total of 150 responses were systematically collected and stored in a digital database. Among these, 120 met the validity criteria after screening. Volunteers were invited to rate each indicator on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (i.e., very dissatisfied) to 5 (i.e., very satisfied) based on their subjective experiences. The full questionnaire and results are provided in Appendix B.

Statistical analysis identified seven critical walkability indicators, each with separate mean scores above 3.85. We used this value as the threshold based on a notable division among mean scores across indicators, where values clustered either above 3.85 or below 3.5 at this point (Fig. 3). These seven indicators became the secondary evaluation indicators for our model. To facilitate quantitative evaluation, we grouped these seven indicators into four categories as the first-level indicators22: Greenness23, Openness35, Crowdedness22 and Safety36. Supplementary Figure S3 shows visual examples of these four categories. Among them, Greenness quantifies street vegetation coverage on streets. It was calculated as the proportion of vegetation pixels from four-directional street view images at each sampling point, then averaged across all points per street. Openness refers to the proportion of sky view from pedestrian viewpoints through street view images. Crowdedness captures the intensity of pedestrians and vehicle traffic flows on the street. It is measured through two metrics: space occupancy rate and traffic flow intensity. The space occupancy rate was computed based on the number of pixels of pedestrians and non-motor vehicles. The traffic flow intensity was calculated using the Amap congestion index. Finally, Safety was evaluated through three metrics: sidewalk proportion (i.e., ratio of sidewalk pixels to road pixels), safety facilities (i.e., presence of traffic signs, crossing facilities, and separation barriers), and sidewalk parking behavior (i.e., presence of vehicles parked on sidewalks). Detailed definitions and equations for all indicators are presented in Table 1.

Data integration and perception-based weight calculation

Our walkability assessment framework integrates objective street-level attributes with perception-based weights for each street view imagery. For objective measures, we quantified street features through DS-HRNet semantic segmentation of street view imagery along street segments. For each street segment, we calculated the average proportion of street features from all its sampling points. For perception-based weights, we employed Shannon’s entropy method to analyze subjective ratings (Eq. 1), following the established approaches33,37.

where \({x_i}\) (i = 1, 2, …, 7) represents the raw measurements of each second-level indicator (e.g., vegetation pixels and sky pixels), \(g\left( {{x_i}} \right)\) represents the calculated indicator values following the formulas in Table 1 (e.g., vegetation coverage rate and sky visible ratio), and \({w_i}\) represents the corresponding subjective weight for each indicator. The weight calculation involves six steps:

Step1: Create a data matrix X (Eq. 2) to organize all measurement data, where m rows corresponding to individual streets and n columns representing the second-level indicators, respectively. The parameter\(~{X_{ij}}\) indicates the value of the j-th indicator of the i-th street.

Step2: Due to the diverse units and dimensions across second-level indicators (e.g., meters, counts, ratios), we normalized the original matrix X to create a dimensionless matrix X′. The transformation of each element Xij to X’ ij followed Eq. (3) for positive indicators (where higher values are preferred) and Eq. (4) for negative indicators (where lower values are preferred), where Xj denotes the j-th indicator vector across streets.

Step3: Calculate the proportion (P’ ij) based on normalized values X’ ij (Eq. 5), where m represents the total number of streets.

Step4: Calculate information entropy (ej) and utility value (dj) according to Eqs. (6) and (7), respectively.

Step5: Normalize the utility value dj to obtain the final weight Wj (Eq. 8), where n represents the total number of second-level indicators.

Step6: Calculate the street walkability based on Eq. (9), where i ranges from 1 to n.

Walkability perception validation and micro-level analysis

We recruited another 30 volunteers to validate our perception-weighted model. Each volunteer was randomly assigned 20 different sampling points from our previously collected dataset. For each point, we showed street view images from four directions (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°). The volunteers rated the walkability of each location on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (i.e., low walkability) to 5 (i.e., high walkability) based on their subjective experiences (questionnaire details in Appendix C). Spearman’s correlation test was applied to examine the relationship between subjective ratings and predicted walkability scores from DS-HRNet model. To evaluate the practical application of our model, we conducted a comprehensive case study in Wuhan city, China. We evaluated spatial patterns of walkability at both community level and hierarchical street level (i.e., primary, secondary, tertiary, and residential). Finally, we examined walkability equity by investigating the association with multiple demographic factors (including non-local household registration, age groups, education level, gender ratio, and per capita room number) using Spearman correlation analysis.

Ethic statement

Ethic approval was waived due to the nature of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Validation of walkability assessment model

To evaluate segmentation performance, we compared DS-HRNet with six widely used semantic segmentation models (FCN, SegNet, PSPNet, DeepLabV3, DeepLabV3+, and HRNet) on the Cityscapes dataset, as shown in Table 2. The results show that DS-HRNet achieved a 1.28% higher mIoU than the baseline HRNet model, showing advanced performance in street scene analysis. We further tested the DS-HRNet model on street view images of Wuhan to validate its performance in real-world urban environments (Fig. 4). We found that DS-HRNet maintains high segmentation accuracy and robust generalization ability even in previously unseen street scenes. Beyond semantic segmentation validation, we assessed the walkability perceptual accuracy of our model through subjective evaluation. Validation results showed a strong positive correlation (Coefficient = 0.73, P < 0.01) between subjective ratings and predicted walkability scores. This confirms model capability in capturing perceived walkability.

The walkability Estimation of Wuhan City

The walkability assessment reveals distinct spatial patterns at both community level and street level in Wuhan. Specifically, the walkability score was classified into five levels using the Natural Breaks (Jenks) method in ArcGIS. This method was chosen as it minimizes variance within classes and maximizes variance between classes, providing a robust classification based on the estimation results for Wuhan38. In our study area, the central urban areas exhibit poor walkability (scores < 0.34). Furthermore, areas with contrasting walkability levels (i.e., high and low) are often spatially adjacent (Fig. 5a). For example, the Wansongyuan community, which contains several commercial centers (Guoguang and Wuguang), shows high walkability due to its well-planned environment. However, adjacent areas including Hanshui Bridge and Ronghua communities show lower walkability. Similar patterns exist around the Minzu community, where the Yanjiang One shopping mall area has high walkability while surrounding areas score much lower (detailed in Supplementary Fig. S4). This spatial pattern reveals an unbalanced distribution of walkable environments throughout the city. At the street level, the analysis reveals diverse patterns of walkability scores (Fig. 5b). Streets with high walkability scores (scores > 0.55) are predominantly found on primary and secondary roads, representing 67% of all high-walkability streets. In contrast, residential roads and paths only account for 6% and 5% of high-walkability streets respectively. Among low-walkability streets (scores < 0.24), residential and tertiary roads account for 45% and 17% respectively.

Spatial Distribution of Walkability Scores in Wuhan (a) Community-level walkability distribution showing the spatial variation of walkability scores across different communities (b) Hierarchical street-level walkability distribution reflecting the pedestrian accessibility along different road networks.

We selected a series of sample streets to demonstrate the walkability evaluation results (Fig. 6). The primary road (Peace Avenue) and secondary road (Yanhe Avenue) show relatively high walkability scores of 0.58 and 0.54 respectively, reflecting their well-developed pedestrian infrastructure and balanced spatial layout. In contrast, tertiary road (WenSheng Street, 0.30), residential road (Xinhua Road, 0.15), and path road (unnamed path, 0.17) demonstrate lower walkability scores. The variation in scores reflects the distinct characteristics and functions of different road hierarchies in the urban transportation network.

We further explored the relationships between walkability scores and multiple socio-demographic factors, including proportion of non-local residents, age structure, education level, gender ratio, and housing conditions (See Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table 3). Among them, the proportion of non-local residents shows negative correlation (Coefficient = -0.301, p < 0.01). Other significant correlations include the proportion of highly educated residents (Coefficient = 0.290, p < 0.01), per capita number of rooms in the household (Coefficient = 0.247, p < 0.05), and children under 14 years old (Coefficient = 0.228, p < 0.01), all showing positive relationships with walkability.

Discussion and conclusions

Our research optimized the automated assessment of urban walkability by developing a high-precision deep learning model (DS-HRNet) for street view segmentation and proposing a comprehensive framework for predicting perceived walkability. First, we developed a high-precision deep learning model (DS-HRNet) for street scene segmentation, achieving a 1.28% improvement in mIoU over the baseline HRNet model. This robust semantic information extraction establishes a reliable foundation for automated walkability assessment. Second, we established a comprehensive framework for perceived walkability prediction to bridge the objective street features with human perception. The significant association between model predictions and human ratings (R2 = 0.73, P < 0.01) validates our model in walkability assessment.

The distribution of walkability in Wuhan exhibits substantial spatial disparities. The commercial areas exhibit high walkability scores, reflecting their well-planned pedestrian environment designed for retail activities. However, the benefits of these walkable spaces do not spread to surrounding residential areas. The walkability level presents distinct differences between commercial centers and their adjacent areas. This observation is consistent with previous research demonstrating that concentrated single-use areas, especially retail parks and office complexes, lead to uneven walkability distribution39. On the street scale, primary roads achieve high walkability through their complete pedestrian infrastructure. However, residential roads, where daily pedestrian activities take place, have received less attention and show lower walkability. Similar patterns have been observed in Taipei24where primary and secondary roads demonstrated higher perceived walkability scores than alley segments. While primary roads focus on efficient mobility, residential streets normally function as essential spaces for community interaction and daily activities. Addressing this disparity is critical for promoting both community vitality and public health outcomes.

Our walkability assessment reveals socio-spatial disparities in urban walkable environments. Overall, communities with social advantages (e.g., highly educated residents and enhanced housing quality) present better walkability scores. In contrast, areas with a high proportion of non-local populations exhibit low walkability scores. This finding aligns with previous research showing that people with low-income and certain minority groups tend to live in areas with lower walkability24,40. Additionally, the proportion of old adults aged 60 and above (Coefficient = 0.050, p = 0.696) was not significantly associated with walkability. This may be attributed to the fact that in these cities older adults live with their adult children41providing them with alternative mobility options beyond walking. Similarly, gender ratio (Coefficient = -0.038, p = 0.697) showed no significant association with walkability in our study. This aligns with a 2023 Shanghai study which demonstrated that males and females shared similar perceptions of walkability42. In conclusion, disadvantaged groups were marginalized with limited access to high-quality walking environments. Promoting spatial equity of walkability is beneficial to improving overall social equality in a macro city.

Furthermore, this study offers important implications for public health policies. Existing research has shown that for each one-unit increase in neighborhood walkability, residents are 4% more likely to engage in outdoor walking activities43. Our findings demonstrate that there are significant disparities in walking environments across communities, and these spatial inequalities may potentially influence the health status of residents44. In low-income communities, limited walkability may be associated with challenges for physical activity, which could negatively impact health outcomes44. To address these challenges, policymakers are suggested to optimize walkability in underserved areas, enhance pedestrian infrastructure for vulnerable populations, and integrate walkability assessment into public health evaluations. Promoting equitable access to high-quality walkable environments holds promise for further enhancing public health equity, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and resilient urban life quality.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, our DS-HRNet model performed well in the street view image analysis. However, since these images were retrieved from Baidu at different times, they may not represent real-time walking environments. Second, since this research was limited to a single city (i.e., Wuhan), the model feasibility in other cites requires further validation. Third, while we validated the model results through surveys, the limited sample size of 120 volunteers and the potential bias in age, income and occupation distribution may also influence result reliability. Furthermore, our model does not consider temporal variations in walking environments, such as the changing weather conditions. Finally, the socioeconomic analysis was constrained by data availability at the micro-scale level, potentially limiting our understanding of fine-grained social disparities in walking environments.

In addition, certain important indicators related to walkability were not included in this study due to data limitations. For example, environmental factors such as noise levels, air quality, and lighting conditions, which potentially affect pedestrian comfort and safety, were not considered45,46. Behavioral data, including pedestrian flows, walking patterns, and trip purposes across different demographic groups, were also absent47,48,49. Furthermore, urban infrastructure indicators, such as public transport accessibility, the density of public facilities, and the availability of barrier-free or inclusive design features, were not included50,51,52. These factors are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of walkability. In addition, future research could (1) incorporate time-series street view data to capture environmental dynamics, (2) validate the model across different cities, (3) expand the survey sample size with more diversity in age groups and occupations, (4) integrate seasonal factors and weather conditions into the assessment framework, and (5) utilize more detailed socioeconomic data to understand social inequalities in walking environments.

In conclusion, this paper presents an evaluation of walking environments in Wuhan through integrating a high-precision deep learning model (DS-HRNet) with human perceptions. First, our DS-HRNet model demonstrates high accuracy in automatically evaluating walking environments based on human perceptions. Second, our assessment indicates distinct disparities in walking quality throughout Wuhan. Primary roads and commercial areas present advanced conditions, while residential streets exhibit poor walking conditions. Third, we found that areas with high concentrations of non-local residents exhibit poor walking conditions, while areas with highly educated residents and good housing conditions tend to have high walkability scores. It indicates that marginalized social groups experience limited access to high-quality walking infrastructure. These findings highlight the urgent need for targeted policy interventions to enhance walking infrastructure in residential areas and promote equitable access to high-quality walking environments across all social groups.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All source code for element recognition in street view images including model architecture, and walkability metric computation will be permanently accessible via figshare upon article publication: https://figshare.com/s/8a7618660278c47b7ec9.

References

Maghelal, P. K., Capp, C. J. & Walkability A review of existing pedestrian indices. J. Urban Reg. Inform. Syst. Association 23, 253 (2011).

Frank, L. D. et al. Chronic disease and where you live: built and natural environment relationships with physical activity, obesity, and diabetes. Environ. Int. 158, 106959 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Association between community walkability and hypertension: evidence from the Wuhan chronic disease cohort study. Environ. Res. 263, 120071 (2024).

Zhang, L., Zhou, S., Kwan, M. P. & Shen, M. Assessing individual environmental exposure derived from the Spatiotemporal behavior context and its impacts on mental health. Health Place. 71, 102655 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Longitudinal associations between neighbourhood physical environments and depressive symptoms of older adults in Hong kong: the moderating effects of terrain slope and declining functional abilities. Health Place. 70, 102585 (2021).

Kaplan, R. & Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

Larkin, A., Gu, X., Chen, L. & Hystad, P. Predicting perceptions of the built environment using GIS, satellite and street view image approaches. Landsc. Urban Plann. 216, 104257 (2021).

Guan, F. et al. Modelling people’s perceived scene complexity of real-world environments using street-view panoramas and open geodata. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 186, 315–331 (2022).

Stokols, D. On the distinction between density and crowding: some implications for future research. Psychol. Rev. 79, 275 (1972).

Han, X., Wang, L., Seo, S. H., He, J. & Jung, T. Measuring perceived psychological stress in urban built environments using Google street view and deep learning. Front. Public. Health. 10, 891736 (2022).

Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (Harvard University Press, 1979).

McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A. & Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health. Educ. Q. 15, 351–377 (1988).

Zhou, H. et al. A multiscale assessment of the impact of perceived safety from street view imagery on street crime. Annals Am. Association Geographers. 114, 69–90 (2024).

Corcoran, R. et al. Perceived neighbourhood affluence, mental health and wellbeing influence judgements of threat and trust on our streets: an urban walking study. PLoS One. 13 (8), e0202412 (2018).

Ewing, R. et al. in Transportation Research Board 92nd Annual Meeting. No. 13-1662.

Weng, M. et al. The 15-minute walkable neighborhoods: measurement, social inequalities and implications for Building healthy communities in urban China. J. Transp. Health. 13, 259–273 (2019).

Huang, X. et al. Comprehensive walkability assessment of urban pedestrian environments using big data and deep learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 26993 (2024).

Sevtsuk, A., Basu, R., Li, X. & Kalvo, R. A big data approach to understanding pedestrian route choice preferences: evidence from San Francisco. Travel Behav. Soc. 25, 41–51 (2021).

McGinn, A. P., Evenson, K. R., Herring, A. H., Huston, S. L. & Rodriguez, D. A. Exploring associations between physical activity and perceived and objective measures of the built environment. J. Urb. Health. 84, 162–184 (2007).

Schlossberg, M., Johnson-Shelton, D., Evers, C. & Moreno-Black, G. Refining the grain: using resident-based walkability audits to better understand walkable urban form. J. Urbanism: Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 8 (3), 260–278 (2015).

A Adams, M. et al. Validation of the neighborhood environment walkability scale (NEWS) items using geographic information systems. J. Phys. Activity Health. 6 (s1), S113–S123 (2009).

Li, Y., Yabuki, N., Fukuda, T. & Integrating, G. I. S. Deep learning, and environmental sensors for multicriteria evaluation of urban street walkability. Landsc. Urban Plann. 230, 104603 (2023).

Ki, D. & Chen, Z. Walkability inequity in Los angeles: uncovering the overlooked role of micro-level features. Transp. Res. Part. D: Transp. Environ. 122, 103888 (2023).

Lu, Y. & Chen, H. M. Using Google street view to reveal environmental justice: assessing public perceived walkability in macroscale City. Landsc. Urban Plann. 244, 104995 (2024).

Ta, D. T. & Ta, D. T. Google street view and machine Learning—Useful tools for a street-Level remote survey: A case study in Ho Chi minh, Vietnam and ichikawa, Japan. Land 11 (12), 2254 (2022).

Wang, R., Lu, Y., Wu, X., Liu, Y. & Yao, Y. Relationship between eye-level greenness and cycling frequency around metro stations in shenzhen, china: A big data approach. Sustainable Cities Soc. 59, 102201 (2020).

Ma, X. et al. Measuring human perceptions of streetscapes to better inform urban renewal: a perspective of scene semantic parsing. Cities 110, 103086 (2021).

Haklay, M. & Weber, P. Openstreetmap User-generated street maps. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 7, 12–18 (2008).

Hou, Y. et al. Global Streetscapes—a comprehensive dataset of 10 million street-level images across 688 cities for urban science and analytics. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 215, 216–238 (2024).

Zhou, H., He, S., Cai, Y., Wang, M. & Su, S. Social inequalities in neighborhood visual walkability: using street view imagery and deep learning technologies to facilitate healthy City planning. Sustainable Cities Soc. 50, 101605 (2019).

Cordts, M. et al. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 3213–3223 (2016).

Wei Zhen, K. C. & Kwan, M. P. Yinghong jiang,qiushi feng. Measuring the age-friendliness of streets’ walking environment using multi-source big data: a case study in shanghai, China. Cities 148, 104829 (2024).

Yilei, T., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Tian, G. & Zhangl, S. Measuring the correlation between human activity density and streetscape perceptions: an analysis based on Baidu street view images in zhengzhou, China. Land 11 (3), 400 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. The relationship between visual enclosure for neighbourhood street walkability and elders’ mental health in china: using street view images. J. Transp. Health. 13, 90–102 (2019).

Dai, L. et al. Analyzing the correlation between visual space and residents’ psychology in wuhan, China using street-view images and deep-learning technique. City Environ. Interact. 11, 100069 (2021).

Gao, W. et al. Assessment of sidewalk walkability: integrating objective and subjective measures of identical context-based sidewalk features. Sustainable Cities Soc. 87, 104142 (2022).

Gu, P., Han, Z., Cao, Z., Chen, Y. & Jiang, Y. Using open source data to measure street walkability and bikeability in china: a case of four cities. Transp. Res. Rec. 2672(31), 63–75 (2018).

Rząsa, K. & Ciski, M. Determination of the level of sustainable development of the cities-a proposal for a method of classifying objects based on natural breaks. Acta Scient. Polonorum Administr. Locorum 20, 215–239 (2021).

Lamíquiz-Daudén, J. C. P. & Manuel Benito-Moreno,Patxi, J. Beyond land use mix, walkable trips. An approach based on parcel-level land use data and network analysis. J. Maps 17 (1), 23–30 (2021).

Knight, J., Weaver, R. & Jones, P. Walkable and resurgent for whom? The uneven geographies of walkability in buffalo, NY. Appl. Geogr. 92, 1–11 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association of living arrangements with depressive symptoms among older adults in china: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 19, 1–10 (2019).

Gong, W., Huang, X., White, M. & Langenheim, N. Walkability perceptions and gender differences in urban fringe new towns: a case study of Shanghai. Land 12, 1339 (2023).

Clevenger, K. A., Berrigan, D., Patel, S., Saint-Maurice, P. F. & Matthews, C. E. Relationship between neighborhood walkability and the prevalence, type, timing, and Temporal characteristics of walking. Health Place. 80, 102983 (2023).

Villanueva, K. et al. Does the walkability of neighbourhoods affect children’s independent mobility, independent of parental, socio-cultural and individual factors? Children’s Geographies. 12, 393–411 (2014).

Zeng, F. et al. The effects of acoustic-light-thermal environment quality parameters on pedestrians’ overall comforts in residential districts. Sci. Rep. 14, 19625 (2024).

Ren, X., Li, Q., Yuan, M. & Shao, S. How visible street greenery moderates traffic noise to improve acoustic comfort in pedestrian environments. Landsc. Urban Plann. 238, 104839 (2023).

Jardim, B., de Castro Neto, M. & Barriguinha, A. A street-point method to measure the Spatiotemporal relationship between walkability and pedestrian flow. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 104, 101993 (2023).

Habibian, M. & Hosseinzadeh, A. Walkability index across trip purposes. Sustainable Cities Soc. 42, 216–225 (2018).

Moura, F., Cambra, P. & Gonçalves, A. B. Measuring walkability for distinct pedestrian groups with a participatory assessment method: A case study in Lisbon. Landsc. Urban Plann. 157, 282–296 (2017).

Sun, G. & Lau, C. Y. Go-along with older people to public transport in high-density cities: understanding the concerns and walking barriers through their lens. J. Transp. Health. 21, 101072 (2021).

Sadeghi, O. & Serugendo, G. D. M. Assessing Walkability in Urban Environments: A Comprehensive Overview (Wiley, 2024).

Barrera-Fernández, D. & Hernández-Escampa, M. Mobility in urban events: walkability and accessibility in the Guelaguetza. Ann. Leisure Res. 25, 247–272 (2022).

Funding

Xue Yang is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.42271449).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XY and XZ designed and project and did the initial analysis. TL did the visualization, wrote the draft and did revision. YC and LT did revision. TL and XY contributed equally. All authors approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Li, T., Cao, Y. et al. A novel framework integrating GeoAI and human perceptions to estimate walkability in Wuhan, China. Sci Rep 15, 25377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09779-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09779-1