Abstract

To tackle the challenge of discrete and complex monitoring data generated during high-speed rail tunnel construction, this study proposes a hybrid deep learning model for deformation forecasting. Using 300-hour continuous deformation records from multiple cross-sections of the G Tunnel (March 2023), a novel WOA-CNN-GRU model is developed, integrating data preprocessing, feature extraction, and prediction. The methodology incorporates quadratic exponential smoothing for outlier mitigation, followed by sequential feature extraction using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and bidirectional gated recurrent units (GRUs). Comparative experiments demonstrate the model’s superiority over conventional architectures including RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN-GRU. The WOA-CNN-GRU model achieves an RMSE of 0.1257 mm and a MAPE of 0.51%, significantly outperforming baseline models, with RMSE reductions of 0.9814 mm (RNN), 0.7629 mm (LSTM), 0.4188 mm (GRU), and 0.2292 mm (CNN-GRU), and MAPE improvements of 2.64%, 1.37%, 1.05%, and 0.86%, respectively. Moreover, the model exhibits robust generalization, with average absolute errors below 1 mm and relative errors under 1% across various construction methods and tunnel segments. These results provide compelling evidence for the effectiveness of hybrid intelligent models in capturing nonlinear, spatiotemporal deformation patterns in tunnel engineering. The WOA-CNN-GRU model offers practical guidance for real-time monitoring system development and risk mitigation in civil infrastructure projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

China’s high-speed rail technology is world-leading, and its construction plays a crucial role in the economic and social development of cities along the route. Between 2014 and 2024, China’s high-speed rail network expanded annually, growing from 16,000 km in 2014 to 48,000 km in 2024, with an average annual increase of 3,200 km. As mountain tunnels traverse increasingly complex geological environments, higher stability requirements for surrounding rock are necessary to prevent engineering disasters such as landslides1.The deformation of the tunnel’s surrounding rock directly reflects its stability. Therefore, analyzing and predicting future deformation using existing displacement monitoring data is crucial for guiding high-speed rail tunnel construction2. Many researchers apply mathematical methods and machine learning techniques to data prediction across various industries.

Koopialipoor3 developed a Stack-Tree-KNN-RF-MLP model to predict the modulus of elasticity of granite in relation to rock deformation. The results showed that this model achieved higher predictive accuracy than general models. Xue4 input the parameters selected using the fuzzy Field-Rough Set method into the BPNN model to predict and analyze the non-uniform deformation of soft rock tunnels. Engineering experiments demonstrated that the BPNN model achieved better predictive performance. Fattahi5 applied the Harmony Search Algorithm (HS) to optimize the Support Vector Machine Regression (SVR) model. The optimized model predicted the deformation modulus of the rock mass with a lower error than the SVR-DE and SVR-PSO models. Deng6 employed the finite-discrete element method (FDEM) for numerical simulation and analysis to investigate the deformation and damage mechanisms of tunnel surrounding rock. The study derived prediction equations for the deformation of unsupported tunnels in homogeneous soft rock under hydrostatic geostress and estimated the maximum possible deformation of such tunnels. Qiu7 developed a tunnel section deformation prediction model based on cloud model theory. Rough set theory was applied to determine the weight of each influencing factor, and the cloud model was then used to predict the surrounding rock deformation level. The model’s predictions were compared with actual excavation observations, demonstrating that the improved cloud model achieved higher prediction accuracy. Cui8 developed a nonlinear prediction model for tunnel strain through repeated numerical computations and regression analysis of geological parameters, including support pressure, ground stress, and GSI. The model was then applied to calculate the strain of a circular bore tunnel in softened rock. While prior research has primarily utilized mathematical methods and traditional machine learning techniques to develop deformation prediction models in different fields, there is still a notable lack of application of deep learning models.

While prior research has primarily utilized mathematical methods and traditional machine learning techniques to develop deformation prediction models in different fields, there is still a notable lack of application of deep learning models. Consequently, researchers have explored the application of deep learning techniques for deformation prediction in recent studies. Shi9 developed a time-series and spatial prediction model using the SVM information granulation algorithm, enhancing the accuracy and stability of tunnel surrounding rock deformation predictions. He10 and colleagues developed an LSTM network model to predict tunnel vault settlement using a recursive neural network algorithm. The LSTM model’s predictions outperformed those of the traditional curvilinear model in practical applications. Dong11 proposed a time-series traction method based on the inversion of mechanical parameters to predict tunnel surrounding rock deformation. The ACSSA algorithm was used to optimize the initial parameters of the ELM and AMLSTM neural networks, forming the ACSSA-ELM and ACSSA-AMLSTM algorithms. A time deformation sequence model was constructed to achieve intelligent prediction of tunnel surrounding rock deformation. Li12 proposed the Bi-LSTM-LGBM model, integrating Bi-LSTM and Light GBM, and used the Liangwangshan Tunnel dataset to compare its performance with other models. The results demonstrated that the Bi-LSTM-LGBM model exhibits strong generalization ability in tunnel deformation prediction. Yao13 developed a WOA-LSTM model based on deep learning theory and applied it to predict surrounding rock deformation in high geostress tunnels. The results indicated that the model achieved higher accuracy in predicting tunnel settlement and convergence. Ye14 employed the LSTM model to develop a new time deformation sequence model for predicting tunnel structure deformation. The measured data from subway construction were input into both the LSTM and RNN models, and the results showed that the LSTM model achieved higher prediction accuracy. Zhang15 combined the CNN and LSTM algorithms to design the FDNN model and analyzed its performance using various metrics. The results demonstrated that the model exhibits high accuracy and strong robustness. Chen16 designed two deep learning models, ANN and LSTM, to predict frozen deformation of railroad roadbeds. The models were trained with data collected from an actual project, and the comparison showed that the LSTM model outperformed the ANN model. Dong17 introduced an autoregressive recurrent network model (DeepAR) to predict the probability of slope instability. The prediction accuracy of DeepAR was verified using goodness-of-fit, demonstrating that the model exhibits excellent safety control and prediction accuracy in practical engineering. Cao18 established a hybrid CNN-LSTM model to capture the deformation trend of the dam and mapped the relationship between load and residuals using the ELM training model. This enabled the prediction of deformation fluctuations and successfully predicted the dam’s deformation. Li19 applied BP neural network theory to construct a model for predicting roadway deformation under high dynamic loads. The model was trained using sample data and tested with an error feedback learning algorithm, demonstrating good accuracy and reliability. Liu20 proposed the MHA-ConvLSTM model for dam deformation prediction, which is typically susceptible to redundant features and weak generalization. By integrating the attention mechanism and convolution algorithm, the model’s performance was enhanced. A comparison with the benchmark model confirmed the accuracy and effectiveness of the MHA-ConvLSTM model in predicting dam deformation. Pei21 developed a nonlinear mapping model for landslide deformation by optimizing the BP algorithm with LSTM, improving the accuracy of landslide disaster prediction. The optimized BP algorithm, along with other improved BP algorithms, was tested for landslide displacement prediction. Results showed that the LSTM-optimized model achieved the best prediction performance. Xi22 proposed a GRU model for long- and short-term dam deformation prediction to enhance monitoring accuracy. The model was trained using monitoring data from a hyperbolic arch dam, showing superior robustness and prediction accuracy compared to the LSTM model. Cai23 predicted landslide deformation from a generative perspective by combining VAE and GRU to create the VAE-GRU framework. The prediction quality was evaluated using corresponding metrics, and the results surpassed the state-of-the-art (SOTA) model in both accuracy and reliability. Ding24 applied the Fbprophet algorithm in Python to train and generate a prediction model for canal slope deformation. The prediction results were compared with MT-InSAR monitoring values, and the analysis showed that the model outperformed others, demonstrating its applicability to predicting slope deformation in deep foundation pit sections. Fu25 studied the deformation of large-span prestressed structures and introduced the PCA algorithm to optimize the GPR, creating the PCA-GPR deformation prediction model. The model’s validity was tested using simulated structural deformation data from Hangzhou Stadium, and the results demonstrated that the model can effectively evaluate the deformation of large-span structures. Qiu26 and colleagues optimized the CDBN model using the LM algorithm to create the LM-CDBN model. They applied the SAA to obtain deformation data from real-time inspections of CITIC Tower and analyzed and predicted the monitoring data with the LM-CDBN model. The results showed that the LM-CDBN model provided better accuracy and fit in predicting the deformation trends of ultra-high-rise buildings. While existing studies have leveraged deep learning models to achieve deformation prediction across diverse engineering scenarios, their optimization processes often succumb to local optima due to the absence of inherent global search mechanisms in bio-inspired algorithms. This limitation constrains prediction accuracy in complex geological contexts.

In summary, existing studies present the following limitations. In high-speed railway tunnel applications that demand high deformation sensitivity, current methodologies exhibit several key shortcomings: (1) Limited predictive accuracy: Artificial neural network (ANN)-based models are constrained by a limited number of neurons and shallow architectures, resulting in substantial prediction errors; (2) Susceptibility to local optimization: Traditional gradient descent algorithms, when combined with bio-inspired optimization techniques that lack global convergence guarantees, are prone to becoming trapped in local optima during parameter tuning; (3) Inadequate spatiotemporal feature fusion: Existing models do not effectively integrate temporal dynamics with spatial structural characteristics, thereby limiting the accurate interpretation of complex deformation patterns.

Therefore, this paper proposes a hybrid CNN-GRU architecture that integrates convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with gated recurrent units (GRUs). This framework not only enhances the complementary extraction of spatial and temporal features, but also mitigates local convergence issues by employing parameter initialization based on the bio-inspired Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA). Ultimately, the proposed model achieves a synergistic balance between model complexity and predictive accuracy.

2 Principles of predictive modeling

Recurrent neural networks

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are a class of deep learning architectures designed to process time-series data. Fundamentally, RNNs propagate hidden-state information across sequential time steps via recurrent connections, enabling the modeling of variable-length sequences. The operational principle of RNNs is illustrated in Fig. 1.

(1) Input Sequence: a text sequence or time series can be divided into multiple time steps, denoted as t.

(2) Hidden State: at each time step t, the network maintains a hidden state st, representing the internal memory at that step.

(3) Forward Propagation: at each time step, the following operations are performed:

(i) The linear combination of inputs and hidden states, as shown in Eq. (1):

where, xt is the input at time step t; U is the weight matrix from the input to the hidden state; W is the weight matrix from the hidden state to the hidden state; st-1 is the hidden state at the previous time step t-1; and bh is the bias term.

(ii) Apply the activation function as shown in Eq. (2):

(iii) Calculate the output as shown in Eq. (3):

(4) Hidden state pass: pass the hidden state of the current time step t to the next time step t + 1 after forward propagation,

(5) Output: generate a yt at each time step.

(6) Backpropagation: involves computing the loss function, calculating the gradient, propagating the gradient, and updating the parameters to train the RNN algorithm.

Long Short-Term memory

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are an advanced variant of recurrent neural networks (RNNs). They transmit information along temporal sequences while maintaining stable gradients that neither vanish nor explode. Their connection weights are updated at each time step, enabling the network to selectively retain relevant information and discard irrelevant inputs through gated mechanisms. These features make LSTMs particularly well-suited for processing sequential data. The architecture of the LSTM gating unit is illustrated in Fig. 2.

-

(1)

Forget gate.

The forget gate is used to determine how much information in the cell state ct-1 of the previous moment can be retained to ct, filtering the invalid information to the model thus speeding up the training, which is calculated in Eq. (4):

where, the value of ft represents the proportion of forgotten information in the cell state ct-1 at the previous moment.

-

(2)

Input gate.

The input gate is used to control how much information in the current input xt can be added to the cell state \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{c}}_{t}\) to realize the state update of \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{c}}_{t}\). The calculation is shown in Eqs. (5) and (6):

where, the output ht-1 at moment t−1 and the input xt at moment t are jointly processed by the sigmoid function as some it in the interval (0, 1), which represents how much of the information in xt is retained.

-

(3)

Output gate.

The output gate is based on the ct after updating and controls how much information of the ct can be used in the calculation of the LSTM output value ht. The formulas for its calculation are shown in Eqs. (7) and (8):

Output gate control unit state ct how many outputs are available into the current output value ht of the LSTM.

In Eq. (5)−(8), ct-1 and ct denote the state variables of the memory cells at t−1 and t moments, which run through the whole network and play the role of transmitting information; \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{c}}_{t}\) denotes the state of the cell at t moments; xt denotes the input at t moments; \(\:\sigma\:\) denotes the sigmoid activation function; ht-1 and ht denote the state variables of the hidden layer at t−1 and t moments; “×” denotes the outer product of vectors; “+” denotes superposition.

CNN-GRU model

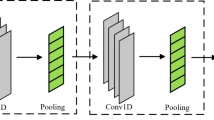

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are deep learning architectures originally developed for image processing, but they have also demonstrated effectiveness in handling time-series data. CNNs utilize convolutional kernels (filters) to perform convolution operations that capture local features and progressively extract higher-level representations through stacked convolutional and pooling layers. CNNs are primarily employed for processing data with lattice-like structures, such as in object detection tasks. The convolution operation between the input feature map III and the convolution kernel KKK is defined in Eq. (9):

where, \(\:{x}_{m}^{n}\) is the output feature of the m-th unit in the n-th layer; Dm is the position of the convolution kernel corresponding to the input feature; \(\:{x}_{m}^{n-1}\) is the input feature of the mth unit in the (n-1)-th layer; \(\:{w}_{im}^{n}\) is the weight between the i-th unit of the n-th layer; and \(\:{\text{b}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{n}}\) is the bias of the m-th unit in the n-th layer.

The gated recurrent unit (GRU) is a variant of the recurrent neural network (RNN) architecture that often surpasses both RNN and LSTM in terms of accuracy and generalization, particularly when the number of model parameters is fixed. GRUs employ a reset gate to determine whether information from previous time steps should be retained, an update gate to regulate the extent to which current information is passed forward, and a candidate activation to update the hidden state. These operations are iteratively executed until convergence or predefined criteria are satisfied. Therefore, GRUs are well-suited for modeling long sequences and effectively mitigating the vanishing gradient problem.

In Eqs. (10)-(13): rt is the reset gate vector; Wr is the reset gate weight matrix; ht-1 is the hidden state of the previous time step; xt is the input of the current time step; br, bh, and bz are the bias terms; \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{h}\) is the candidate hidden state vector; Wh is the candidate hidden state weight matrix; zt is the update gate vector; Wz is the update gate weight matrix; and ht is the current time step hidden state at the current time step.

The CNN-GRU model is a comprehensive neural network architecture comprising a CNN layer, a GRU layer, and a fully connected layer. The CNN layer is responsible for spatial feature extraction and consists of an input layer, a convolutional layer, and a pooling layer. The GRU layer extracts temporal features and consists of an input layer, a hidden layer, and a hidden output layer. The fully connected layer maps the features to the predicted values and contains an output layer. The principle of the CNN-GRU neural network is shown in Fig. 3.

-

Whale Optimization Algorithm.

The Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) is a population-based intelligent optimization algorithm known for its few parameters and fast convergence. WOA consists of three main actions: encircling the prey, foaming net attack, and random prey search.

(1) Surrounding the prey.

The WOA algorithm takes the current optimal candidate solution as the target prey (optimal solution), and after knowing the prey position the whales start to update the position based on the current relationship between themselves and the prey position. As shown in Eqs. (14) and (15):

where, t denotes the current number of iterations, \(\:{\overrightarrow{X}}^{*}\left(t\right)\) denotes the position of the optimal candidate solution before generation t, \(\:\overrightarrow{X}\left(t\right)\) and \(\:\overrightarrow{X}\left(t+1\right)\) denotes the solution of generation t and t+1. \(\:\overrightarrow{A}\) and \(\:\overrightarrow{C}\) are coefficient vectors, and the computational formulas are shown in Eqs. (16) and (17):

where, \(\:\overrightarrow{{r}_{1}}\) and \(\:\overrightarrow{{r}_{2}}\) denote random numbers between (0,1); \(\:\overrightarrow{{a}_{1}}\) denotes a number that decreases linearly from 2 to 0, as shown in Eq. (18):

where, G represents the total number of iterations.

(2) Foamnet Attacks.

To simulate the humpback whale’s foaming net attack, a spiral equation was established between the whale and the prey to model the whale’s spiral motion, as shown in Eqs. (19) and (20):

where, b is a constant, typically 1, and l is a random number between [−1, 1].

Humpback whale encircling prey and foam net attacks were randomly selected, and would encircle prey when probability p < i, and use foam nets in total when probability p ≥ i, as shown in Eqs. (21) and (22):

(3) Randomized search for prey.

Randomized search is used in WOA for global search to jump out of the local optimum, as shown in Eqs. (23) and (24):

where, \(\:\overrightarrow{{X}_{rand}}\) is a randomly selected whale and the direction of the random search is determined by one random whale. When \(\:\left|A\right|<1\) adopts the encircling prey behavior, when \(\:\left|A\right|>1\) adopts the random search behavior.

3 Project overview and monitoring program

Project overview

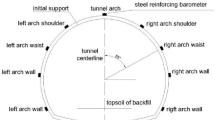

The G tunnel, located in Jiangmen City, Guangdong Province, extends from DK18 + 875 to DK34 + 029.655, with a total length of 15.15 km. It traverses a geologically anomalous zone, where detailed investigations have identified a densely jointed zone and a rock mass ranging from fractured to severely broken. The tunnel adopts a single-bore, dual-lane design, incorporating one vertical shaft and one inclined shaft, and constitutes a time-critical segment of the entire line. Construction of the G tunnel is executed using two distinct methods, selected based on the varying engineering geological conditions: the step excavation method and the shield tunneling method. Specifically, the tunnel sections from DK24 + 660 to DK27 + 325 and from DK31 + 288.5 to DK34 + 029.655 are constructed using the step excavation method, whereas the section from DK27 + 325 to DK31 + 288.5 is constructed using the shield tunneling method. The tunnel sections constructed using the step excavation and shield tunneling methods are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively.

Tunnel construction monitoring program

Surface settlement monitoring program

The primary objective of surface settlement monitoring in tunnel construction is to collect data on surface deformation induced by construction-related disturbances, track the deformation process, and promptly forecast potential hazards based on monitoring frequency and established control standards. Furthermore, it serves as a critical reference for optimizing construction parameters.

First, the reference point is established in a geologically stable area beyond the influence zone of tunnel construction, and verification measurement points are installed to ensure the reliability and stability of the collected data. After surface monitoring points are installed ahead of the vertical tunnel axis in the portal and shallow-buried gully sections, settlement observation points are symmetrically arranged at regular intervals on both sides of the tunnel centerline. The monitoring width on each side of the tunnel centerline is not less than H0 + B. The layouts of the measurement points are illustrated in Fig. 6 for the conventional tunnel section and in Fig. 7 for the shield-driven section.

The installation of surface settlement measurement points involves using a core drilling machine equipped with a 140 mm diameter drill bit to penetrate the road’s hardened surface layer until the original soil stratum is reached. After cleaning the borehole, water is injected to maintain moisture. A 20 mm diameter steel rebar is then positioned along the central axis of the borehole, with its top end approximately 5 cm below ground level. The bottom of the borehole is filled with approximately 15 cm of cement mortar, while the upper portion is backfilled with fine sand and compacted using manual vibration techniques. The backfill height is maintained approximately 5 cm below the end of the rebar. Finally, a protective sleeve is installed, and the measurement point number is marked on the surface. The burial and protective arrangement of the surface settlement measurement points are illustrated in Fig. 8.

The initial elevation is then determined using the third-class leveling method and by jointly measuring the working base point and the nearby datum point. During monitoring, the elevation difference between the survey point and the datum point is measured to obtain the elevation Δht1, which is then compared with the last measured elevation Δht0 to calculate the settlement value ΔH of the point:

Horizontal convergence and vault subsidence monitoring program

Monitoring horizontal convergence provides real-time data on the deformation of the surrounding rock during tunnel excavation. Analysis of these data reveals deformation patterns, which inform the optimization of tunnel construction parameters and the design of support structures. Additionally, it contributes to minimizing the ecological impact of high-speed railway tunnel construction.

The construction of the G tunnel employs both the step method and the shield method, depending on the prevailing geological conditions. The arrangement of measurement points for horizontal convergence monitoring varies according to the construction technique: the step method involves measurements at each excavation step, whereas the shield method focuses on monitoring at segment joints. The tunnel vault, which bears the pressure exerted by the surrounding soil, plays a critical role in ensuring the safety and stability of the tunnel. Measured vault subsidence serves as a key indicator of changes in the surrounding rock, structural behavior, and support system performance. The horizontal convergence and vault subsidence monitoring schemes for tunnels constructed using the step method and the shield method are illustrated in Figs. 9 and 10, respectively.

4 Algorithmic applications

Monitoring data and pre-processing

The monitoring dataset comprises 300 representative deformation measurements collected across different construction methods and monitoring sections during the construction of Tunnel G, spanning from April 2022 to March 2023. The data sources are summarized in Table 1.

The presence of outliers in the monitoring data can negatively impact model training accuracy, reduce generalization capability, and impair the quality of data fitting. Therefore, noise reduction preprocessing is essential. In this study, the quadratic exponential smoothing method—a time series analysis and forecasting technique—is employed to preprocess the data. This method assigns greater weights to more recent data points and lower weights to older ones, thereby effectively reducing noise.

The equations are provided in Eqs. (26) and (27):

where, Ft is the predicted value at this moment; \(\:\alpha\:\) is the smoothing parameter, [0,1]; Yt is the observed value at moment t; Lt-1 is the observed value at the previous moment; Lt is the horizontal value at moment t.

The monitoring data are normalized and linearly scaled into the range [0, 1]. The normalization formula is presented in Eq. (28).

Where, X is the original value; Xn is the normalized eigenvalue; Xmax is the original maximum value; Xmin is the original minimum value.

To prevent overfitting and improve the model’s generalization and stability, the normalized dataset is divided into training and testing subsets according to a predefined ratio. Specifically, 70% of the data is allocated for training, while the remaining 30% is used to evaluate the model’s performance and generalization capability.

Deep learning model construction

Deep learning architectures can be categorized into various types based on tasks, data types, network structures, and other criteria. Based on network structure, representative models include Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN), CNN, RNN, Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), Graph Neural Networks (GNN), and Attention Mechanisms. The characteristics and application scenarios of different neural networks—such as CNN, RNN, GAN, GNN, and Attention Mechanisms—differ significantly, as summarized in Table 2.

This paper primarily uses deep learning models such as RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN-GRU, and the basic steps for constructing these models are outlined below.

The data preprocessing and model training pipeline can be summarized as follows: First, data preparation involves collecting representative, high-quality datasets, removing redundant or noisy entries, and extracting relevant multidimensional features. Next, data normalization is applied to ensure that input features are on comparable scales. A suitable model architecture is then selected and designed based on the specific task requirements. Appropriate activation functions, loss functions, and optimizers are chosen to facilitate effective learning. The dataset is subsequently divided into training, validation, and test subsets according to the task type, and mini-batch training is employed to accelerate convergence. During model compilation and training, parameters such as learning rate, batch size, and number of epochs are configured. The training process is monitored using loss functions and evaluation metrics to prevent overfitting. The model is subsequently evaluated on the test set using various metrics, and loss and accuracy curves are plotted to assess its performance. Finally, model performance and generalization are further improved by refining the architecture, tuning hyperparameters, selecting suitable optimizers, and applying regularization techniques.

Deep learning model construction combining bionic algorithms

Bionic algorithms are optimization methods that address practical problems by mimicking biological processes, evolutionary mechanisms, or ecological behaviors observed in nature. Their core principle is to replicate the behaviors, evolutionary patterns, and adaptive strategies of organisms in nature to identify optimal or near-optimal solutions.

Step 1: Create a time-series dataset by splitting the data into input sequences and their corresponding target values. Use the np.reshape function to add a temporal dimension, transforming the data from “(number of samples, number of features)” to “(number of samples, number of features, number of time steps)” to meet the CNN-GRU model’s input requirements.

Step 2: Import the Sequential model from the Keras library, configure network parameters such as the number of convolutional kernels, kernel size, and activation function, and apply zero-padding to maintain consistent input and output sizes, thereby creating a CNN-GRU model.

Step 3: Evaluate the current solution by training the model, adjusting the number of neuron nodes in the GRU layer, setting the activation function, and calculating the error between the model’s output and the monitoring value. Use the gradient descent formula to update the weights, checking if the maximum iteration count (200) or accuracy requirements are met. If not, continue training; otherwise, stop and save the optimal weight matrix. Then, pass the complete sequence to the fully connected layer. Finally, train the model using the Adam optimizer and evaluate accuracy using the mean square error (MSE) loss function.

Step 4: Define the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) and use it to optimize the model’s hyperparameters or weights. Then, train the final CNN-GRU model using the WOA-optimized parameters, and evaluate the model’s performance by monitoring the loss function and accuracy.

Step 5: Once training is complete, save the optimal model weights for future use.

Indicators for evaluating the effectiveness of forecasting

This paper uses the root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) as indicators to measure the error between predicted and actual values. The RMSE has the same unit as the original target value, making it easier to compare, while the MAPE measures the relative error. Therefore, RMSE and MAPE are selected as the evaluation metrics for the model’s performance, with their calculation formulas shown in Eqs. (29) and (30).

Where, n is the total number of samples; y is the actual value of the ith sample; \(\:\widehat{y}\) is the predicted value of the ith sample.

Comparison model parameter selection

To assess the predictive performance of the WOA-CNN-GRU model for construction monitoring data in high-speed rail tunnels, this study compares its results with those of four neural network models: RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN-GRU. The parameter settings for both the baseline models and the WOA-CNN-GRU model are listed in Table 3.

Deep learning model construction

Model accuracy analysis

The surface settlement dataset DK24 + 985:Z1, collected from the step-method section, is employed as input data to evaluate the training accuracy of various models. Initially, the training dataset is fed into five models—RNN, LSTM, GRU, CNN-GRU, and WOA-CNN-GRU—to compare their training performance. The training results of each model are presented in Fig. 11, while the corresponding loss function curves are illustrated in Fig. 12. As shown in Figs. 11 and 12, all models achieve a prediction accuracy exceeding 95% when applied to surface settlement forecasting in the step-method section. This indicates that while all models exhibit strong performance, variations in accuracy still exist.

As illustrated in Figs. 11 and 12 and summarized in Table 4, the WOA-CNN-GRU model achieves an RMSE of 0.1257 mm in predicting construction deformation in high-speed rail tunnels. In comparison, the RMSE values for the RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN-GRU models are 0.9814 mm, 0.7629 mm, 0.4188 mm, and 0.2292 mm, respectively. The model also yields a MAPE of 0.51%, whereas the corresponding values for the RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN-GRU models are 2.64%, 1.37%, 1.05%, and 0.86%, respectively. Moreover, the WOA-CNN-GRU model exhibits the lowest testing and validation losses at 0.8 × 10⁻⁵ and 2.1 × 10⁻⁵, respectively. In contrast, the other models produce significantly higher values for these metrics.

The model’s absolute prediction accuracy improves by factors of 6.8, 5.1, 2.3, and 0.8 compared to the RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN-GRU models, respectively. Similarly, its relative prediction accuracy increases by factors of 4.2, 1.7, 1.1, and 0.7. These results demonstrate that the WOA-optimized CNN-GRU model significantly outperforms conventional deep learning models in terms of predictive performance. Therefore, the WOA-CNN-GRU model can accurately forecast surface settlement and horizontal convergence in tunnel construction, thus contributing to improved safety in high-speed rail tunnel engineering.

Model accuracy analysis

The trained WOA-CNN-GRU model is applied to various work methods, sections, and monitoring data, with the comparison between predicted and actual values shown in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13; Table 5, the RMSE and MAPE between actual and predicted monitoring data across different sources during high-speed rail tunnel construction are consistently below 1 mm and 1%, respectively. These results indicate that the WOA-CNN-GRU model is highly effective and reliable for predicting surrounding rock deformation. Its application can contribute to improved construction efficiency and reduced project costs.

5 Conclusion

(1) This paper develops a WOA-CNN-GRU hybrid neural network model grounded in recurrent neural network theory, capable of more accurately predicting surrounding rock deformation in high-speed rail tunnel construction employing various methods.

(2) Quadratic exponential smoothing is employed to mitigate anomalies in surrounding rock deformation data during high-speed rail tunnel construction, effectively reducing noise and enhancing the accuracy of the time series prediction model.

(3) Using monitoring data from the DK24 + 985:Z1 section, the WOA-CNN-GRU model significantly outperforms RNN, LSTM, GRU, and CNN-GRU models, achieving RMSE and MAPE values of 0.1257 mm and 0.51%, respectively. Its accuracy improves by factors of 6.8, 5.1, 2.3, and 0.8 relative to these models.

(4) Applied to five additional datasets, the WOA-CNN-GRU model attains an average absolute prediction error below 1%, demonstrating its value as a reliable tool for deformation prediction in high-speed rail construction, thereby enhancing efficiency and reducing costs.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sun, Z., Zhang, D., Hou, Y., Li A. Whole-process deformation laws and determination of stability criterion of surrounding rock of tunnels based on statistics of field measured data. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 43 (07), 1261–1270 (2021).

Zhang, X. & Wang, C. Analysis of the stability of tunnel surrounding rock and ground settlement in soft layered foundatio. Chinese Journal of Underground Space and Engineering, 18(S1):396–403. (2022).

Koopialipoor, M. et al. Introducing stacking machine learning approaches for the prediction of rock deformation. Transp. Geotechnics. 34, 100756 (2022).

Xue, Y. et al. Analysis of the factors influencing the nonuniform deformation and a deformation prediction model of soft rock tunnels by data mining. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 109, 103769 (2021).

Fattahi, H. Application of improved support vector regression model for prediction of deformation modulus of a rock mass. Eng. Comput. 32 (4), 567–580 (2016).

Deng, P., Liu, Q., Liu, B. & Lu, H. Failure mechanism and deformation prediction of soft rock tunnels based on a combined finite–discrete element numerical method. Comput. Geotech. 161, 105622 (2023).

Qiu, D. et al. Prediction of the surrounding rock deformation grade for a High-Speed railway tunnel based on rough set theory and a cloud model. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. - Trans. Civil Eng. 45, 303–314 (2021).

Cui, L. et al. Regression model for predicting tunnel strain in strain-softening rock mass for underground openings. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 119, 81–97 (2019).

Shi, S. et al. Intelligent prediction of surrounding rock deformation of shallow buried highway tunnel and its engineering application.Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 90(8):1–11. (2019).

He, Y. & Chen, Q. Construction and application of LSTM-Based prediction model for tunnel surrounding rock deformation. Sustainability 15 (8), 6877 (2023).

Dong, F., Wang, S., Yang, R. & Yang, S. Time-series traction prediction of surrounding rock deformation in tunnel construction based on mechanical parameter inversion. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 152,105933. (2024).

Li, Z., Ma, E., Lai, J. & Su, X. Tunnel Deformation Prediction during Construction: an Explainable Hybrid Model Considering Temporal and Static Factors. Computers & Structures, 294, 107276 , (2024).

Yao, J., Nie, J. & Li, C. Research on prediction of surrounding rock deformation and optimization of construction parameters of high ground stress tunnel based on WOA-LSTM. Sci. Rep. 14(1): 27396. (2024).

Ye, X. et al. LSTM-based deformation forecasting for additional stress Estimation of existing tunnel structure induced by adjacent shield tunneling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 146, 105664 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. The construction and application of a deep Learning-Based primary support deformation prediction model for large Cross-Section tunnels. Appl. Sci. 14 (2), 912 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Zhou, T. A deep learning forecasting method for Frost heave deformation of high-speed railway subgrade. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 185, 103265 (2021).

Dong, M. et al. Deformation prediction of unstable slopes based on Real-Time monitoring and DeepAR model. Sensors 21 (1), 14 (2020).

Cao, E., Bao, T., Yuan, R. & Hu, S. Hierarchical prediction of dam deformation based on hybrid Temporal network and load-oriented residual correction. Eng. Struct. 308, 117949 (2024).

Li, A. et al. Deformation and failure laws of surrounding rocks of coal roadways under high dynamic load and intelligent prediction. Sustainability 15 (2), 1313 (2023).

Liu, H., Li, D. & Ding, Y. MHA-ConvLSTM dam deformation prediction model considering environmental volume lag effect. Appl. Sci. 13 (14), 8538 (2023).

Pei, Z. & Huang, Y. Prediction of sliding slope displacement based on intelligent algorithm. Wireless Pers. Commun. 102, 3141–3157 (2018).

Xi, N., Yang, Q., Sun, Y. & Mei, G. Machine learning approaches for slope deformation prediction based on monitored Time-Series displacement data: A comparative investigation. Appl. Sci. 13, 4677 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Generative probabilistic prediction of precipitation induced landslide deformation with variational autoencoder and gated recurrent unit. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1394129 (2024).

Ding, L. et al. Slope deformation prediction based on MT-InSAR and Fbprophet for deep excavation section of South–North. Water Transf. Project Sustain. 14 (17), 10873 (2022).

Fu, W. et al. Deformation prediction model of large-span prestressed structure for health monitoring based on robust Gaussian process regression. Eng. Struct. 318, 118597 (2024).

Qiu, D. et al. Deformation prediction approach for supertall Building using sensor monitoring system. J. Sens. 2019 (1), 9283584 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and C.Z.; methodology, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z., C.Z. and W.D.; formal analysis, Y.Z., C.Z. and W.D.; investigation, Y.Z., C.Z. and W.D.; resources, C.Z.; data curation, Y.Z., C.Z. and W.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., C.Z. and W.D; visualization, W.D.; supervision, W.D. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Cheng, Z. & Wu, D. Deep learning driven prediction and comparative study of surrounding rock deformation in high speed railway tunnels. Sci Rep 15, 24104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09791-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09791-5