Abstract

This study evaluates the impacts of construction activities from the Ulu Jelai Hydroelectric Project on the water quality of the Susu Reservoir, a critical freshwater system in Malaysia fed by the Telom, Mensun, Bertam, Menlock, Lemoi, and Tekai rivers. A systematic spatial–temporal analysis was conducted using 15 water quality monitoring stations (WQ1–WQ18), strategically distributed across tributaries, inflow points, and the Susu Dam. Key physicochemical, biological, and hydrological parameters, including turbidity, total suspended solids (TSS), pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), ammonia (NH3-N), E. coli, and oil and grease (O&G), and flow rate, were analyzed across wet and dry seasons. The results revealed significant seasonal variability in water quality parameters. Dry periods were characterized by elevated DO, O&G, and flow rate levels with an average of 8.98 mg/L, 1932.98 mg/L, and 7.48 m3/s, respectively, alongside reduced TSS and E. coli with an average of 300.23 mg/L and 656.47 CFU/100mL, respectively. In contrast, wet seasons exhibited heightened turbidity, BOD, and nutrient influx, with an average of 201.73 NTU, 1.84mg/L, and 0.16 mg/L, due to runoff within the Upper Susu Watershed. Principal component analysis (PCA) attributed dry-season conditions to climatic and physicochemical drivers, whereas wet-season water quality degradation correlated with anthropogenic activities, such as agricultural runoff, livestock operations, and rainfall conditions. Turbidity levels exceeded regulatory thresholds at multiple monitoring stations, underscoring localized sediment mobilization near construction zones. The findings underscore the cumulative impacts of land-use practices and hydroelectric infrastructure on reservoir integrity. Elevated contaminant levels, driven by seasonal hydrological dynamics and anthropogenic pressures, necessitate adaptive management strategies. This study provides a framework for balancing hydroelectric development with ecological sustainability in tropical montane systems, emphasizing evidence-based practices to minimize anthropogenic degradation in freshwater reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pursuit of societal progress, marked by population growth, technological advancement, and ambitious infrastructure development, has disrupted the equilibrium of global ecosystems1. The construction of large-scale infrastructure, such as dams and reservoirs, driven by the increasing demand for energy and water, has long-lasting impacts on the environment2. While these projects address critical water and energy needs, they also disrupt ecological equilibrium through sediment loading, altered hydrological regimes, and water quality degradation3,4,5. This influx of sediment, often accompanied by nutrient release, thermal stratification changes, and oxygen depletion, can severely degrade water quality within reservoirs and downstream, compromise dam integrity, and exacerbate erosion6. Consequently, robust environmental assessment and management are paramount during such developments. Empirical evidence underscores the necessity of elucidating the mechanistic linkages between anthropogenic disturbances associated with construction activities and aquatic system degradation to formulate targeted mitigation protocols, ensuring regulatory compliance and ecological resilience in tropical reservoir systems7.

In Malaysia, where natural lakes are scarce, over 90 constructed freshwater reservoirs are essential for water supply, hydroelectric power generation, and rainwater management8. The push for sustainable energy heavily relies on hydroelectric projects like the Ulu Jelai Hydroelectric Project (UJHP)8,9. While crucial for national energy goals (UJHP capacity: 372 MW10), the associated large-scale constructions, such as earthworks, tunnelling, and dam building, invariably impact environmental sustainability and water resources11. These impacts manifest as degraded water quality, including heightened turbidity, pH shifts, and oxygen depletion12. Despite mitigation aims outlined in regulations like the Environmental Quality Act 1974, evidence suggests current practices may be insufficient; research indicates construction sediment alone can increase turbidity by as much as 200%13. This starkly demonstrates the urgent need for more rigorous site-specific monitoring and demonstrably effective mitigation strategies during such developments.

Integrating empirical findings like those from this study into decision-making frameworks is critical for project developers, regulators, and policymakers across Southeast Asia14 striving for more sustainable water management aligned with regional environmental guidelines. Despite increasing recognition of hydropower project impacts, critical knowledge gaps persist in understanding how seasonal dynamics interact with specific construction and operational activities to drive water quality fluctuations in tropical reservoirs. Notably, there is a lack of in situ data evaluating the real-world effectiveness of environmental mitigation strategies during high-impact project phases, such as construction and initial reservoir operation. This study addresses these gaps through a focused case study of Malaysia’s Susu Reservoir, part of the Ulu Jelai Hydroelectric Project (UJHP), which receives inflows from the Telom, Mensun, Bertam, Menlock, Lemoi, and Tekai rivers. The research aims to quantify construction-driven perturbations in the reservoir’s hydrochemical regimes, analyze seasonal and activity-linked variations in key water quality parameters such as nutrient levels, turbidity, and dissolved oxygen, and assess the performance of implemented mitigation measures in minimizing ecological disruptions. By integrating empirical data with contextual analysis, this work provides actionable insights for optimizing environmental management practices and shaping evidence-based policies to reduce the ecological footprint of future hydropower projects in tropical regions.

Materials and methods

Study area and description

The Susu Reservoir, part of the Susu Dam in Cameron Highlands, Pahang, Malaysia, supports water supply, flood control, and hydroelectric power generation. The reservoir, with a full supply level at an elevation of 540 m, has a gross storage capacity of 26.14 million m3, including live and dead storage capacities of 14.70 and 4.00 million m3, respectively. Its catchment area, with 157.6–228 km2 and linked intakes including Telom, Lemoi rivers, is critically impacted by steep-slope agriculture, including tea, vegetables, and flowers, tourism infrastructure, and rapid urbanization. Unmanaged land-use practices, such as road construction and deforestation, exacerbate soil erosion and sediment transport into the reservoir, worsened by the region’s steep terrain and heavy rainfall.

Sampling station selection and water quality index (WQI)

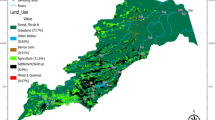

Fifteen monitoring stations (WQ1-WQ18) assessed spatial–temporal variability in physical, chemical, biological, and hydrological parameters to quantify sediment mobilization and contaminant influx from anthropogenic disturbances. Integrated analysis of physicochemical and hydrological data identified localized and cumulative impacts on reservoir integrity, informing adaptive mitigation strategies to balance energy infrastructure development with ecological sustainability in tropical montane watersheds. Water samples were collected monthly from each sampling location. The specific details for each of the river and stream water monitoring locations are presented in Table 1, while their spatial distribution is depicted in Fig. 1.

(a) General map indicating the locations of Water Quality Monitoring Stations., (b) Detailed map of Susu Dam, highlighting key features and monitoring points (c), a Satellite image of the sampling location, providing a visual context for the study area Source: The map in Fig. 1 was created using QGIS v3.40 (https://qgis.org). The base map utilizes open-access data from OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright). Regarding the satellite imagery, it is an RGB basemap of Google Maps (tile maps service), which is based on WorldView-3.

The average flow rate of each of the stream flows was obtained by dividing the stream cross-section into segments where the respective velocity and area of each segment were measured. At each segment, the current speed was measured at a single point at 0.6 m of depth from the surface to the bottom, before being multiplied by the area to obtain the segmental flow rate. The average flow rate is the summation of all segmental flow rates. An example of the flow measurement is shown in the following model, average velocity and average flow rate of the river and/or stream shall be computed as follows in Eqs. (1, 2): -

where:

V = velocity.

A = Area.

Qaverage = total flow rate.

The water quality parameters gathered in this study were evaluated against the threshold limits set by Malaysia’s Department of Environment (DOE) under the National Water Quality Standards (NWQS) for Malaysia (1996; formerly referred to as the Interim National Water Quality Standards, INWQS). Additionally, WQI, developed by the Malaysian Department of Environment, was employed to assess water quality (Table 2). This index, which combines six key variables, DO (Dissolved oxygen), COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand), BOD (Biological Oxygen Demand), O&G (Oil and Grease), pH (Potential of Hydrogen), and NH3-N (Ammonia Nitrogen), provides an overall water quality rating. The parameters were selected and weighted using an expert opinion poll. The WQI equation is then used to classify water quality that corresponds to the NWQS classifications.

Analytical techniques of water quality parameters

During this study, critical in-situ water quality parameters, temperature, pH, and DO were measured on-site using a YSI 556 multi-parameter probe, following American Public Health Association (APHA) standards to ensure accuracy and consistency. Prior to sample collection, all instruments, including the YSI 556 probe, were calibrated using standardized protocols to guarantee the reliability of measurements for temperature, pH, DO, and turbidity. Water samples were collected at designated monitoring sites, preserved under refrigerated conditions (4°C) during transportation, during transport, and transferred to the laboratory for subsequent analysis. These samples were tested for a range of parameters, including TSS, O&G, NH3-N, E. coli, BOD, and COD. The combination of on-site measurements and laboratory analyses. A summary table(S4) details all analyzed parameters, including TSS, turbidity, pH, DO, COD, BOD, ammoniacal nitrogen, oil and grease, and Escherichia coli (E. coli), alongside their respective analytical methods and references, such as APHA method numbers or HACH protocols15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was conducted on monthly monitoring data collected over 12 months to identify trends and correlations. Methods included regression analysis and ANOVA. A range of methods were used for this purpose, including linear regression to explore relationships between two variables and multivariate regression to explore multiple variables. Comparative methodologies such as the Pearson correlation test and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) were used to compare the dataset between different groups and assess the correlation between variables. Boxplots were used for visualization, and residual analysis was used to verify model assumptions. While these are the primary methods, advanced statistical methods and machine learning algorithms were also used to augment predictive precision, and further analysis was completed using a range of computational tools and software to manage complex statistical models. By combining these techniques, a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the intricate data relationships is achieved.

Results

Water quality variables distribution and concentration

The variations in water temperature, turbidity, TSS, pH, DO, BOD, COD, NH3-N, O&G, E. coli levels, and flow rate in the Susu Reservoir during the dry and rainy seasons are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The water quality analysis revealed distinct seasonal differences in these parameters. During the wet season, the average values of water temperature, turbidity, TSS, pH, BOD, COD, NH3-N, and E. coli were higher compared to the dry season. Specifically, the wet season averages were 22.54°C for water temperature, 201.73 NTU for turbidity, 329.71 mg/L for TSS, 7.14 for pH, 1.84 mg/L for BOD, 13.89 mg/L for COD, 0.16 mg/L for NH3-N, and 1263.95 CFU/100 mL for E. coli. In contrast, during the dry season, the corresponding averages were 21.37°C for water temperature, 182.51 NTU for turbidity, 300.23 mg/L for TSS, 7.05 for pH, 1.45 mg/L for BOD, 10.98 mg/L for COD, 0.11 mg/L for NH3-N, and 656.47 CFU/100 mL for E. coli as shown in Fig. 2a.

Conversely, the dry season saw greater levels of DO, O&G, and flow rate. During the dry season, the mean readings for DO, O&G, and flow rate were 8.98 mg/L, 1932.89 mg/L, and 7.48 m3/s, respectively. During the wet season, the averages were slightly lower, with 8.97 mg/L for DO, 426.95 mg/L for O&G, and 5.91 m3/s for flow rate as shown in Fig. 2b.

These findings underscore the impact of seasonal variability on water quality in the Susu Reservoir. During the wet season, elevated levels of suspended solids, organic pollutants, and microbial contamination were observed, whereas the dry season exhibited higher dissolved oxygen, oil-and-grease concentrations, as well as increased flow rates, a trend potentially driven by regulated dam discharges upstream or lower evaporation rates under dry conditions. This pattern aligns with findings from the Puah Reservoir22, where similar seasonal trends were documented. Such variations are crucial for deciphering the reservoir’s ecological dynamics and devising targeted water management strategies to mitigate pollution risks.

S5, presents the correlation matrix for the wet season, detailing the relationships between various water quality parameters in the Susu Reservoir. A moderate positive correlation was observed between turbidity and TSS (r = 0.49), suggesting that suspended solids may contribute to water cloudiness, though additional factors likely influence turbidity levels. The positive correlation between BOD and NH3-N (r = 0.59) suggests that organic pollution drives up ammoniacal nitrogen concentrations, likely due to microbial decomposition processes23. While a moderate correlation exists between NH3-N and E. coli (r = 0.60), implicating fecal contamination as a partial ammonia source, further investigation is needed to disentangle contributions from agricultural inputs, decaying vegetation, or sediment release. Negative correlations were observed between turbidity and pH (r = − 0.52) and between COD and NH3-N (r = − 0.70). The inverse relationship between turbidity and pH suggests that elevated suspended solids correlate with lower pH values, likely due to acidic compound release, including organic acids from decomposing organic matter or hydrogen ion (H⁺) adsorption onto sediment surfaces, thereby altering aqueous-phase acidity. Similarly, the COD-NH3-N correlation implies that higher COD may reduce ammonia levels, potentially through oxidation processes converting NH3-N to nitrate (NO3⁻) under aerobic conditions24,25. The positive correlation between flow rate and turbidity (r = 0.52) suggests that elevated water flow from upstream discharges may enhance sediment resuspension, mobilizing particulate matter into the water column. These correlations emphasize the interconnected nature of water quality parameters, with organic pollution, sedimentation, and fecal contamination identified as important factors influencing water quality. A clear understanding of these dynamics, including the quantified impacts of rainfall intensity and runoff volume on sediment mobilization, is critical for effective reservoir management, particularly during the wet season when these processes exacerbate water quality degradation26.

Analysis of the correlation matrix for the dry season (S6) reveals important relationships between key water quality parameters. Strong positive correlations were identified between turbidity and TSS (r = 0.90), and between NH3-N and E. coli (r = 0.92). These correlations were significantly stronger during the dry season compared to the wet season. This seasonal contrast is likely driven by dilution effects during the wet season, where increased rainfall and runoff disperse suspended solids and fecal contaminants, weakening the observed relationships. Conversely, lower flows and stagnation during the dry season appear to concentrate particulates and microbial indicators, thereby amplifying these correlations. Furthermore, the strong positive correlation specifically observed between turbidity and NH3-N during the dry season (r = 0.75) suggests that sediment resuspension, promoted by low flow conditions, mobilizes particulate-bound ammonium, such as that associated with organic matter or adsorbed ammonium. into the water column. Conversely, a strong negative correlation between COD and NH3-N (r = − 0.82) indicates that higher chemical oxygen demand is linked to a reduction in ammonia levels, likely through oxidation. Strong correlations between water temperature and pH (r = 0.91) and BOD (r = 0.78) reflect two key mechanisms: warmer temperatures stimulate algal photosynthesis, reducing CO₂ and raising pH, while accelerating microbial decomposition of organic matter, increasing BOD. These thermally driven processes highlight how seasonal warming amplifies both alkalinity and organic pollution in aquatic systems. The high correlation between TSS and E. coli (r = 0.86) suggests that suspended solids may act as carriers for fecal bacteria. In contrast, flow rate demonstrates minimal correlations with most other parameters, which suggests it has little direct influence on water quality during the dry season and that other processes are the main driving factors. The data demonstrate an interconnected nature of water quality and identify organic pollution, sedimentation, and fecal contamination as key drivers27. These findings show that the dry season presents a unique set of environmental factors that are important to consider when developing a management plan for this reservoir.

Characteristics of water quality in the wet season

During the monitoring period, the wet season (March to October) recorded an annual average rainfall of 2,311 mm, with particularly intense precipitation during the Southwest Monsoon (SWM) from May to September, averaging 866 mm/month28. This heavy rainfall significantly influenced water quality trends, as elevated pollution loads reflected in higher Water Quality Index (WQI) values were observed in wet season months compared to dry season months (October to February). The increase in pollution correlates with frequent flooding during heavy rains, which transports organic matter, sediments, and nutrients from surrounding watersheds into reservoirs, elevating physicochemical parameters such as turbidity and nutrient concentrations. These inputs decline during the dry season when reduced rainfall and runoff limit external contributions.

PCA of the wet season water quality data, identified four principal components (PCs) with eigenvalues > 1, which together explained 77.182% of the aggregate variation (S2). S7 and S8 provide a summary of the particular findings of this PCA analysis. The colored points and ellipses on Fig. 3 reveal groupings of different sampling sites, demonstrating that certain sites are associated with distinct combinations of these parameters. Sites in Group A (red) exhibit characteristics linked to elevated suspended solids, while Group C (blue) shows higher concentrations of COD, suggesting conditions such as low organic input or stable flow that may inherently reduce pH and BOD compared to Group A. In contrast, Group B (green) is associated with higher pH, dissolved oxygen, and markers of organic pollution, including NH3-N and E. coli. Overall, the biplot highlights how distinct combinations of parameters influence water quality in the Susu Reservoir during the wet season, with each sampling site reflecting unique environmental or anthropogenic drivers.

Of the dataset’s total variance, Principal Component 1 (PC1) explained 36.209% of it. In the water, PC1 showed substantial negative loadings for turbidity, TSS, and COD, and significant positive loadings for pH, BOD, NH3-N, and E. coli levels. These patterns indicate that PC1 was primarily influenced by physical and chemical factors associated with the wet season. During this period, high rainfall contributed to elevated NH3-N levels in the Susu Reservoir. Additionally, agricultural activities, settlements, and livestock farming in the upstream Susu Watershed significantly impacted the reservoir’s water quality29,30. Rainfall during the wet season (May–September), characterized by intense precipitation averaging 866 mm/month, transported fertilizer residues, and domestic waste, into the reservoir, elevating nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) levels and turbidity31. Elevated turbidity in the reservoir was linked to runoff from surrounding land interacting with the Susu Dam infrastructure. Concurrently, reduced solar radiation during the wet season’s overcast conditions contributed to lower water temperatures. These findings underscore the complex interplay of land use practices, seasonal rainfall patterns, and water quality parameters in the Susu Reservoir.

The variation was explained by Principal Component 2 (PC2) in 17.085% of cases. Temperature, oil and grease (O&G), and flow rate all showed notable positive loadings in PC2. This suggests that the primary drivers of PC2 were hydrological causes, notably discharge from the Susu Watershed and increased water volumes during the period of heavy rainfall32. Discharge bringing domestic waste and oil and grease residues from the watershed increased O&G concentrations in the Susu Reservoir. Furthermore, the dilution of the water body caused by the increased water volume from rainfall, runoff, and streamflow during the wet season led to higher temperatures and lower levels of TSS. TSS and DO loadings in the water were significantly positive, and Principal Component 3 (PC3) accounted for 13.574% of the variation. In the Susu Watershed, PC3 was driven by intense seasonal rainfall (averaging 866 mm/month) and anthropogenic activities such as improper waste disposal. Rainfall transported domestic waste downstream into the Susu Reservoir, contributing to elevated TSS and fluctuating DO levels.

Of the overall variance, 10.315% was explained by Principal Component 4 (PC4). Considerable negative loadings for water pH were shown by PC4, while considerable positive loadings for temperature were shown. This indicates that PC4 was controlled by seasonal physical parameters. The high temperatures in the Susu Reservoir were influenced by local climatic conditions, while the lower pH values were attributed to acidic rain and chemical runoff carried into the reservoir by rainfall. These factors collectively highlight the complex interactions between climatic conditions, hydrological processes, and human activities in shaping the water quality of the Susu Reservoir.

Characteristics of water quality in the dry season

PCA was applied to dry season water quality data for the Susu Reservoir, resulting in three significant PCs with eigenvalues greater than unity. Together, these components account for 82.328% of the total variance (S9). Full details of the PCA results for the dry season are summarized in S10 and graphically represented in S3.

Figure 4 demonstrates that PC1 is positively correlated with COD and DO, and negatively correlated with Turbidity, O&G, and NH3-N. Likewise, PC2 is positively correlated with pH, BOD, and Temperature. A combination of different factors influences the water quality at the different locations.

PC1, which accounted for 43.334% of the total variance, exhibits strong positive loadings for turbidity, TSS, NH3-N, O&G, and E. coli, and negative loadings for DO and COD. These loadings indicate that PC1 is driven by dry season conditions and nutrient inputs from agricultural activities, including manure waste or organic matter released from areas and rivers adjacent to the Susu Reservoir, contributing to elevated pollution indicators such as NH3-N and TSS levels. During the dry season, high water temperatures, coupled with reduced rainfall, result in low TSS levels. While it was expected that higher nutrient levels from sources such as agriculture would result in low clarity, it is likely that algal growth, which is enhanced by high NH3-N concentrations, contributes to higher turbidity as well as increased pH through photosynthesis33. Additionally, inefficient decomposition of unused food pellets and deceased fish may contribute to the high levels of NH3-N observed.

PCA of the dry season water quality data revealed three key underlying factors, which explain the variance in the dataset. The first factor (F1), which is also PC1, primarily represents a contamination component, showing strong positive loadings for TSS, NH3-N, and E. coli, as well as turbidity and O&G, all of which are often associated with fecal contamination and sediment pollution. Furthermore, this factor also demonstrates negative loadings for COD and DO, suggesting that these parameters are strongly associated with reduced levels of organic waste and biological processes. The second factor (F2) is linked to water chemistry and biological activity, exhibiting high positive loadings for temperature, pH, and BOD, as well as a lower positive loading with DO. Finally, the third factor (F3) is strongly associated with the flow rate, which suggests that variability in this factor is primarily driven by the movement of water throughout the reservoir. Overall, these findings demonstrate that dry season water quality is influenced by a complex interaction of factors, including pollution, biological processes related to temperature, and the flow rate of water. These different factors all contribute in unique and distinct ways to the overall variability in water quality of this reservoir.

Temperature, turbidity, pH, DO, and BOD all showed high positive loadings, and PC2 explained 29.501% of the variance. This implies that during the dry season, PC2 is significantly impacted by the reservoir’s physical and chemical properties. The higher temperatures prevalent during the dry season, while decreasing overall water flow, also encourage algal growth, which increases the pH and DO levels. Conversely, low rainfall during dry periods correlates with reduced COD, as diminished runoff from nearby agricultural lands such as tea plantations, vegetable farms, and floriculture in the Cameron Highlands region that surrounds the study area decreases the influx of NH3-N and pesticides linked to fertilizer and agrochemical applications34. In addition, agricultural practices are the primary driver of elevated nutrient concentrations, which stimulate algal growth. This increase in algal productivity in turn elevates pH and DO through the process of photosynthesis, while the incomplete degradation of the pellets results in high BOD levels. A further 9.493% of the variance was explained by PC3, which showed a negative loading for NH3-N and a substantial positive loading for water flow rate. These loadings suggest that PC3 reflects hydrological conditions and water movement through the reservoir. Moderate flow rates with a daily average (7.48 m3/s) in the Susu Reservoir promote vertical mixing of the water column, while agricultural practices in the surrounding watershed contribute to elevated nutrient levels through runoff.

Discussion

Trends of water quality during the wet season

Rainfall, runoff, and land-use patterns within the Susu Watershed all have a major impact on the water quality of the Susu Reservoir during the rainy season. The wet season is characterized by generally higher levels of pH, DO, NH3-N, E. coli, oil and O&G, and flow rates, while water temperature, TSS, and COD are typically lower. The cloudy weather and high rainfall during this season act to decrease both air and water temperatures. This results in a higher capacity of the water to hold DO35. Further, the high influx of oxygenated waters from the watershed results in further elevation in DO concentrations. The Susu Reservoir’s position within the lower catchment of the watershed makes it a convergence point for pollutants transported by heavy rainfall, such as agricultural runoff and urban waste, which are carried downstream from upstream land-use activities into the reservoir34. The dominant land use patterns in the Susu Watershed, which are agricultural and settlement-based, contribute heavily to this transport. Inorganic fertilizers containing nitrogen, human waste from inadequate sanitation facilities upstream, and untreated livestock manure from surrounding farms34 are transported via runoff into the Susu Reservoir, collectively contributing to elevated nitrogen levels in its waters. These sources, combined with high rainfall, result in a higher concentration of NH3-N in the reservoir, a pattern which is consistent with observations in other similar reservoirs36,37. Additionally, limestone weathering, which is enhanced by rainfall, increases the transportation of CaCO3 into the reservoir, resulting in an elevated PH38,39. Finally, the increased volume of water dilutes various solid materials, leading to decreased TSS levels, which in turn, results in a clearer water clarity and relatively higher levels of O&G, consistent with the findings in Bakun Reservoir, Malaysia40. Though other studies in Mexico showed a contradictory result, with higher rainfall resulting in higher levels of TSS41,42,43, this suggests there are a wide variety of regional variations to these responses.

Overall, the water quality of the Susu Reservoir during the wet season is governed by a complex and interconnected relationship between climatic conditions, watershed characteristics, and human activities. High rainfall acts as a primary driver, mobilizing soil and pollutants from the Susu Reservoir’s watershed, where agricultural land use (5500 ha), urban settlements (2750 ha) result in the accumulation of approximately 400,000 tons of annual sedimentation in the reservoir34. This includes fertilizer residues from croplands, livestock manure from pasture zones, domestic waste from densely populated urban areas, and dissolved limestone. These inputs collectively lead to elevated levels of DO, nutrients, pH, and E. coli, alongside reduced TSS and increased O&G concentrations. This intricate interplay of environmental factors highlights the multifaceted nature of water quality dynamics in the reservoir. Agricultural practices significantly impact water pollution, with cabbage farms losing 154 kg/season/ha of N, P, and K via runoff (vs. 5 kg in chrysanthemum farms) and 193 kg/season/ha via leaching. Runoff NO3⁻–N concentrations reached 25 ppm in cabbage farms, compared to < 10 ppm under rain-shelters34. Animal waste and improperly managed manure further contribute to the presence of E. coli, posing risks to both aquatic ecosystems and human health44. Additionally, rainwater serves as a conduit for transporting oil and grease from urban and industrial sources, such as vehicles, machinery, and paved surfaces, into the reservoir45. This process significantly elevates O&G levels, further degrading water quality.

The seasonal influx of pollutants underscores the vulnerability of the Susu Reservoir to anthropogenic activities and climatic variability. High rainfall (937 mm/month) enhances contaminant transport and alters the water’s physicochemical properties, increasing DO levels through aeration from rainfall and reducing TSS via dilution effects31,46. However, these changes are not uniform and can vary depending on regional characteristics and land-use practices, as evidenced by contrasting findings in other studies, such as higher TSS levels in Mexico during wet seasons42,43.

To address these challenges, a holistic approach to watershed management is essential. This includes implementing sustainable agricultural practices to minimize fertilizer runoff, improving waste management systems to reduce untreated sewage, and promoting better manure management to limit E. coli contamination47,48,49. Public awareness campaigns can also play a crucial role in reducing the discharge of oil and grease from urban areas50. Furthermore, continuous monitoring and adaptive management strategies are needed to account for the dynamic interplay of climatic and anthropogenic factors, ensuring the long-term protection and sustainability of the Susu Reservoir’s water quality. By addressing these issues, stakeholders can mitigate the adverse impacts of wet-season pollution and enhance the resilience of the reservoir’s ecosystem.

Trends of water quality during the dry season

There are significant variations in physical, chemical, biological, and hydrological factors that define the Susu Reservoir’s water quality during the dry season as opposed to the rainy season. The dry season is marked by elevated water temperature, turbidity, pH, DO, BOD, NH3-N, and E. coli levels. Conversely, TSS, COD, O&G, and water flow rates tend to be lower during this period. The combination of low rainfall and high solar radiation, during the dry season results in higher water temperatures, as solar radiation acts as a major heat source for the reservoir51,52. Additionally, the decreased rainfall causes less runoff and erosion from the watershed, even though wind velocity may result in higher water flow and wave height. Since rainfall is the main way that solid materials are distributed into the reservoir, the reduction in rainfall has a direct effect on TSS concentrations53,54. The reduced runoff, associated with a slow flow regime, diminishes the input of COD into the reservoir, primarily sourced from agricultural activity in the watershed. However, the slow flow simultaneously hinders self-purification processes, leading to pollutant accumulation. This issue is exacerbated by rising evaporation rates under high temperatures, which further concentrates pollutants such as NH3-N in the water55. Additionally, increased agricultural activity during the dry season leads to greater runoff of fertilizers, which are typically richer in nitrate than ammonia, but residual ammonium components still contribute to elevated NH3-N levels in the water,56,57.

Agro-ecosystems, a common practice in the surrounding areas of the Susu Reservoir, exacerbate water quality issues, particularly during the dry season, as highlighted by studies such as34,58,59. The deposition of uneaten feed pellets from these aquaculture systems disrupts both aerobic and anaerobic bacterial processes, leading to the release of NH3-N and a reduction in DO levels. This disruption not only affects the chemical balance of the water but also promotes algal growth due to the increased availability of nutrients from the decomposing pellets. The proliferation of algae enhances photosynthetic activity, which temporarily elevates pH and DO levels during daylight hours. However, this effect is diurnal; at night, algal respiration and decomposition deplete oxygen, resulting in a net reduction of DO levels in the water60,61.

Furthermore, the decomposition of organic materials releases NH3-N, which is alkaline, further contributing to higher pH levels in the reservoir. This combination of factors creates a feedback loop where nutrient enrichment from aquaculture activities sustains algal blooms, altering the water’s chemical and biological properties62,63. During the dry season, the situation is aggravated by reduced river and stream flows, which limit the dilution of contaminants. This stagnation creates favorable conditions for bacterial growth, including E. coli, as the lack of flushing and aeration allows bacteria to thrive in the slow-moving or stagnant waters64,65.

Thus, the dry season’s water quality is significantly shaped by a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors. High temperatures and low rainfall amplify the effects of human activities, particularly agricultural practices, which introduce excess nutrients and organic matter into the reservoir. These conditions not only degrade water quality but also pose risks to aquatic ecosystems and human health. For instance, elevated NH3-N levels can be toxic to aquatic organisms, while high E. coli concentrations indicate fecal contamination, raising concerns about water safety for downstream users.

To mitigate these impacts, adopting improved agricultural management practices such as optimizing fertilizer application schedules to minimize nutrient leaching and upgrading waste collection systems to reduce nutrient runoff into waterways is critical66. Concurrently, systematically monitoring and regulating nutrient inputs from agricultural and domestic sources can curb algal blooms and safeguard aquatic ecosystem health. Strengthening public awareness campaigns and enforcing stricter environmental regulations are equally vital to addressing human-driven pollution across the watershed. By addressing these challenges, stakeholders can work toward preserving the ecological integrity and sustainability of the Susu Reservoir, particularly during the vulnerable dry season.

Conclusions

External environmental factors, particularly runoff from the Susu Watershed, strongly influenced the water quality of Susu Reservoir during the wet season (March to October). Elevated levels of pH, DO, NH3-N, E. coli, and increased flow rates were observed, attributed to heavy rainfall washing agricultural, livestock, and domestic waste into the reservoir. Concurrently, the increased water volume led to higher transparency and reduced TSS. Conversely, during the dry season (November to February), water quality was primarily governed by internal reservoir conditions. Elevated solar radiation drove higher water temperatures, while limited rainfall reduced external pollutant inputs, resulting in lower COD and diminished TSS. Meanwhile, accumulations of organic matter from agriculture practices contributed to increased pH, and NH3-N levels likely through nutrient-driven algal growth and decomposition processes, while concurrently reducing turbidity due to settled particulates. Findings from both seasons underscore the adverse impacts of agricultural activities and land use practices in the Susu Watershed on the reservoir’s water quality. Addressing these impacts requires targeted training programs to help farmers adopt efficient agricultural practices, including managing farm density to minimize waste generation and runoff, alongside focused education initiatives on improved manure processing and precision fertilizer application to reduce nutrient pollution, such as NH3-N and NO3-N. Effective watershed management strategies must prioritize organic waste reduction, sediment runoff control through measures like riparian buffers, and enhanced sanitation infrastructure. This study advances SDG 6 (Clean Water) by proposing strategies to curb nutrient pollution (NH3-N, NO3-N) and microbial contamination (E. coli), and supports SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) via sustainable farming practices that balance productivity and environmental protection. Mitigation measures like riparian buffers and precision farming align with SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) by enhancing ecosystem resilience and curbing sediment runoff. The call for integrated watershed management underscores the role of collaborative governance (SDG 17) in harmonizing ecological and socioeconomic goals, fostering an SDG-aligned framework for sustainable hydropower development.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Khir Alla, Y. M.& Liu, L. Impacts of Dams on the Environment: A Review. International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 6(1) (2021).

Ingle, P. V., Gangadhar, M. & Deepak, M. D. Developing a project performance assessment model for benchmarking the project success of Indian construction projects. Benchmarking 31, 1426–1452 (2023).

Ibrahim, A., Zayed, T. & Lafhaj, Z. Enhancing construction performance: a critical review of performance measurement practices at the project level. Buildings 14, 1988 (2024).

Shi, C., Qu, C. & Sun, W. Multimedia distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Wang Lake Wetland. China. Environ. Pollut 306, 119358 (2022).

Astuti, M. P., Notodarmojo, S., Priadi, C. R. & Padhye, L. P. Contaminants of emerging concerns (CECs) in a municipal wastewater treatment plant in Indonesia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 30, 21512–21532 (2023).

Andualem, T. G., Hewa, G. A., Myers, B. R., Peters, S. & Boland, J. Erosion and sediment transport modeling: A systematic review. Land 12, 1396 (2023).

Oyedotun, T. D. T. & Ally, N. Environmental issues and challenges confronting surface waters in South America: A review. Environ. Challenges 3, 100049 (2021).

NAHRIM. Study on the Status of Eutrophication of Lakes in Malaysia. Seri Kembangan. (2009)

Tang, K. H. D. Hydroelectric dams and power demand in Malaysia: A planning Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 252, 119795 (2020).

Abdullah, M. F. If you can control water, you can control everything: Pembangunan Sumber Air Mentah di Negeri Kedah, 1957–1992. Asian J. Environ, History and Heritage 5(1), 1–24 (2021).

Hossaina, M. et al. A state-of-the-art review of hydropower in Malaysia as renewable energy: Current status and future prospects. Energ. Strat. Rev. 22, 426–437 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Assessment of the impact of floods on terrestrial plant biodiversity. J. Clean. Prod 339, 130722 (2022).

Khaddor, I., Achab, M., Soumali, M. R., Benjbara, A. & Alaoui, A. H. The impact of the construction of a dam on flood management. Civ. Eng. J. 7(2), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.28991/cej-(2021)-03091658 (2021).

Thompson, N. S. & Caissie, B. E. Evaluating the paleoenvironmental significance of sediment grain size in Bering Sea sediments during Marine Isotope Stage 11. Stratigraphy 19(2), 119–139 (2022).

Singh, K., Kumar, N., Yadav, A. K., Singh, R. & Kumar, K. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as a health hazard: current state of knowledge and strategies in environmental settings across Asia and future perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 475, 145064 (2023).

Matos, T., Martins, M. S., Henriques, R. & Goncalves, L. M. A review of methods and instruments to monitor turbidity and suspended sediment concentration. J. Water Proc. Eng 64, 105624 (2024).

Dewangan, S. K., Toppo, D. N. & Kujur, A. Investigating the impact of pH levels on water quality: An experimental approach. IJRASET 45(98), 2321–9653 (2023).

Zhang, W., Han, S., Zhang, D., Shan, B. & Wei, D. Variations in dissolved oxygen and aquatic biological responses in China’s coastal seas. Environ. Res 223, 115418 (2023).

Lv, Z., Ran, X., Liu, J. & Jiao, N. Effectiveness of chemical oxygen demand as an indicator of organic pollution in aquatic environments. OLAR https://doi.org/10.34133/olar.0050 (2024).

Aguilar-Torrejón, J. A. et al. Relationship, importance, and development of analytical techniques: COD, BOD, and TOC in water—An overview through time. SN Appl. Sci. 5, 118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-023-05318-7 (2023).

AbdulKadir, W. A. F. W., Omar, R. C. & Shamsudin, M. S. Ammoniacal nitrogen – A critical contaminant in leachate composition: Characteristics, potential risk, and adsorption treatment innovations. J. Water Proc. Eng 62, 105424 (2024).

Fulazzaky, M. A. & Omar, R. Removal of oil and grease contamination from stream water using the granular activated carbon block filter. Clean Technol Envir 14, 965–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-012-0471-8 (2012).

Abubakar, M. K., Ruddin, M. S. A. S., Filza, E. A., Ahmad Nazri, S. & Shahril, M. Assessment of water quality index of Puah Reservoir, Hulu Terengganu, Malaysia. Earth Environ. Sci. 711, 012031 (2021).

Tan, H., Wang, C. & Zhu, S. Neonicotinoids in draining micro-watersheds dominated by rice-vegetable rotations in tropical China: multimedia occurrence, influencing factors, transport, and associated ecological risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 446, 130716 (2023).

Abu Hasan, H., Muhamad, M. H., Budi Kurniawan, S., Buhari, J. & Husain, A. O. J. W. Managing bisphenol A contamination: advances in removal technologies and future prospects. Water 15, 3573 (2023).

Babel, S. et al. Microplastics pollution in selected rivers from Southeast Asia. APN Sci. Bull. 12, 5–17 (2022).

Chow, M. F., Subbramaniam, P. & Sidek, L. M. Assessment of sedimentation problem in Kenyir hydropower reservoir. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 541, 012008 (2020).

Abd Wahab, N. et al. The assessment of sedimentation problems in Kenyir hydropower reservoir. Malaysia. 15(13), 2375. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15132375 (2023).

Wong, C. L., Venneker Uhlenbrook, R. S., Jamil, A. B. M. & Zhou, Y. Variability of rainfall in Peninsular Malaysia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci 6, 5471–5503 (2009).

Debie, E. &Awoke, Z. Assessment of the effects of land use/cover changes on soil loss and sediment export in the Tul Watershed, Northwest Ethiopia using the RUSLE and InVEST models. Int. J. River Basin Manag, 1–16 (2023).

Chan, R., Chiemchaisri, C., Chiemchaisri, W., Boonsoongnern, A. & Tulayakul, P. J. E. C. Occurrence of antibiotics in typical pig farming and its wastewater treatment in Thailand. Emerg. Contam. 8, 21–29 (2022).

Muhammad, N. S., Abdullah, J. & Julien, P. Characteristics of Rainfall in Peninsular Malaysia. J. Phys. Conf. Ser 1529, 052014 (2020).

Rafiei, V., Ghahramani, A., An-Vo, D. A. & Mushtaq, S. Modelling hydrological processes and identifying soil erosion sources in a tropical catchment of the great barrier reef using SWAT. Water 12, 2179 (2020).

Doan, T. O., Duong, T. T., Nguyen, T. M., Hoang, T. Q., Luong, T. T. &Pham, P. T. Preliminary results on microplastic pollution from agricultural soil in Vietnam: distribution, characterization, and ecological risk assessment. (2023)

Aminuddin. B. Y., Ghulam. M. H., Wan Abdullah. W. Y., Zulkefli. M., Salama. R. B. Sustainability of current agricultural practices in the Cameron Highlands, Malaysia. Water Air Soil Pollut, (2005) 5: 89–101

Yao, R., Yao, S. & Ai, T. Organophosphate pesticides and pyrethroids in farmland of the Pearl River Delta, China: regional residue, distributions and risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(2), 1017 (2023).

Klake, R. K., Nartey, V. K., Doamekpor, L. K. & Dinku, D. E. Seasonal variation in water quality of the Weija Dam. Ghana. J. Nat. Sci. Res 5, 20 (2015).

Luckyardi, S., Gaol, T. V. L. & Oktafiani, D. Assessment of the water quality and environmental management in Jangari reservoir watershed using selected physical, chemical, and biological parameters. J. Eng. Sci. Technol 16, 4518–4529 (2021).

Chaidar, A. N., Soekarno, I., Wiyono, A. & Nugroho, J. Spatial analysis of erosion and land criticality of the Upstream Citarum watershed. Int. J. Geomate 13, 133–140 (2017).

Buvaneshwari, S. et al. Potash fertilizer promotes incipient salinization in groundwater irrigated semi-arid agriculture. Sci. Rep 10, 3691 (2020).

Ling, T. Y. et al. Physicochemical parameters of Bakun reservoir in Belaga, Sarawak, Malaysia, 13 months after reaching full supply leve. Sains Malaysiana 45(2), 157–166 (2016).

Rodríguez-Martínez, G. et al. Water erosion, its relationship to total suspended solids and water quality in the lower basin of the Usumacinta River, Tabasco. Mexico. Nat. Environ. Pollut. 20(3), 1097–1106 (2021).

Loaiza, J. G. et al. Assessment of water quality in a tropical reservoir in Mexico: seasonal, spatial and multivariable analysis. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 18, 7456 (2021).

Oliveira, K. L. D., Ramos, R. L., Oliveira, S. C. & Christofaro, C. Water quality index and spatio-temporal perspective of a large Brazilian water reservoir. Water Supply 21, 971–982 (2021).

Alegbeleye, O. O. & Sant’Ana, A. S. Manure-borne pathogens as an important source of water contamination: An update on the dynamics of pathogen survival/transport as well as practical risk mitigation strategies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 227, 113524 (2020).

Müller, A., Österlund, H., Marsalek, J. & Viklander, M. The pollution conveyed by urban runoff: A review of sources. Sci. Total Environ 709, 136125 (2020).

Ariyani, M., Agustian, M., Maharani, G. S. & Sunardi.,. Assessment of Seasonal Trophic State of Tropical Man-Made Lake, the Cirata Reservoir. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 277, 012030 (2019).

Ng, C. H. et al. Plastic waste and microplastic issues in Southeast Asia. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 427 (2023).

Alkhadher, S. A. A. et al. Monitoring of sewage pollution in the surface sediments of coastal ecosystems using linear alkylbenzenes (LABs) as molecular markers. J. Soils Sediments 20, 3230–3242 (2020).

Alkhadher, S. A. A. et al. Assessment of Sewage Molecular Markers in Port Dickson Coast and Kim Kim River with Sediment Linear Alkylbenzenes. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd https://doi.org/10.1080/10406638 (2022).

Suwarno, D., Löhr, A., Kroeze, C. & Widianarko, B. Fast Increases in Urban Sewage Inputs to Rivers of Indonesia. Env. Dev. Sustain 16, 1077–1096 (2014).

Musnansyah, A., Kamil, A. A., Marliana, L., Widayati, E. & Zulfakriza,. Assessment of spatial water quality observation of citarum river bandung regency using multivariate statistical methods. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol 11, 356–362 (2021).

Ling, T. et al. Seasonal changes and spatial variation in water quality of a large young tropical reservoir and Its Downstream river. J. Chem. 2017, 8153246 (2017).

Ngearnpat, N., Klayluk, B., Kumla, A., Ngamta, S. & Issakul, K. Phytoplankton composition and water quality of Kwan Phayao reservoir, Thailand, during rainy and cold dry seasons. J. Food Health Bioenviron. Sci 11, 46–55 (2018).

Castilla-Hernández, P., Torres-Alvarado, M. D. R., Luis, J. A. H. & Cruz-López, N. Water quality of a reservoir and its major tributary located in East-Central Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 6119–6135 (2014).

Ajayan, A. & Kumar, K. G. A. On the seasonal changes in the surface water chemistry of Museum Lake, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. India. Pollution 2, 103–114 (2016).

Shemsanga, C. et al. Origin and mechanisms of high salinity in Hombolo Dam and Groundwater in Dodoma Municipality Tanzania. Revealed. Appl. Water Sci 7, 2883–2905 (2017).

Ariningsih, E., Erwidodo Irawan, A. R. & Saliem, H. P. Dairy Cattle manure utilization by smallholder dairy farmers in West Java Indonesia. E3S Web. Conf. 361, 03013 (2022).

Shabala, A. N., Combrinck, L. & McCrindle, R. Effect of farming activities on seasonal variation of water quality of Bonsma Dam. KwaZulu-Natal. S. Afr. J. Sci 109, 1–7 (2013).

Long, D. T. et al. Influence of rainy season and land use on drinking water quality in a Karst Landscape, State of Yucatán. Mexico. Appl. Geochem 98, 265–277 (2018).

Andriyani, N. et al. Biodiversity of Algae Potentially HABS (Harmfull Algae Blooms) in Reservoir Mrica Banjarnegara. E3S Web. Conf 47, 03001 (2018).

Tromboni, F. et al. Changing land use and population density are degrading water quality in the lower Mekong Basin. Water 13, 1948 (2021).

Anjali, N. et al. Assessment of potentially toxic elements in groundwater through interpolation, pollution indices, and chemometric techniques in Dehradun in Uttarakhand State. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 25, 36241–36263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27419-x (2024).

Matta, G., Nayak, A., Kumar, A., Tiwari, A. K. & Naik, P. K. Evaluation of heavy metals contamination with calculating the pollution index for Ganga River system. Aiwan Water Conserv 68(3), 52–65 (2020).

Marselina, M. & Burhanudin, M. Trophic status assessment of Saguling reservoir, upper Citarum Basin Indonesia. Air Soil WaterRes 10, 1178622117746660 (2017).

Melo, R. R. C. D. et al. Influence of extreme strength in water quality of the Jucazinho reservoir, Northeastern Brazil PE. Water 9, 955 (2017).

Hoang, A. Q. et al. A review on management practices, environmental impacts, and human exposure risks related to electrical and electronic waste in Vietnam: findings from case studies in informal e-waste recycling areas. Environ. Geochem. Health 45, 2705–2728 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The funding for the study was provided by Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) and UNITEN for BOLD Refresh Postdoctoral Fellowships through project code J510050002-IC-6 BOLDREFRESH2025-Center of Excellence. This research also was supported by Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) and UNITEN through the Higher Institution Centre of Excellence (HICoE), Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia under the project code 2024001HICOE as referenced in JPT(BPKI)1000/016/018/34(5).

Funding

This research was supported by Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) and UNITEN through the Higher Institution Centre of Excellence (HICoE), Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia, under the project code 2024001HICOE as referenced in JPT(BPKI)1000/016/018/34(5). The funding for the study was provided by Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) and UNITEN for BOLD Refresh Postdoctoral Fellowships through project code J510050002-IC-6 BOLDREFRESH2025-Center of Excellence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology formal analysis and investigation and writing—original draft preparation: S.A. A.A; L.M.S; M.S.J.K, M.M.A.A and T.A.K Writing review and editing and resources: L.M.S; and T.A.K.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkhadher, S.A.A., Sidek, L.M., Khan, M.S.J. et al. Seasonal variations in water quality and hydrological dynamics in a tropical reservoir driven by rainfall, runoff, and anthropogenic activities. Sci Rep 15, 35589 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09808-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09808-z