Abstract

The issue of multimorbidity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is extremely serious. However, the pattern of multimorbidity, including typical complications, remains unclear. This study aims to explore the current status and influencing factors of multimorbidity in T2DM, with a focus on mining frequent disease combination patterns and strong association rules. Data on 26 diseases were extracted from the electronic medical records of 5,838 hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes. The chi-square test, Cochran-Armitage trend test, and logistic regression were used for the analysis of influential factors. Association rule mining was employed to explore frequent disease combinations and association rules across the entire population and subgroups stratified by gender, age, and BMI. Network graphs were used to visualize binary comorbidity relationships. Gender-specific differences in disease prevalence were found for 18 of the 26 diseases included in this study. The prevalence of multimorbidity was 97.8%, and it increased with age, with a higher prevalence in males (P < 0.05). The identified frequent disease combination patterns mainly centered around typical complications of T2DM. The most frequent binary comorbidity pattern was diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) + diabetic peripheral vascular disease (DPVD) (support: 74.1%), which is a novel finding in the relationship between DPN and DPVD. The primary association rule identified was {DPVD + diabetic nephropathy (DN)}→{Hypertension}. Disease combination patterns and association rules varied across gender, age, and BMI. Comorbidity relationships became more complex in the middle and older age groups, as well as in the overweight and obese groups. The findings of this study can be used to guide clinicians in the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity in T2DM and provide possible directions for researchers to further investigate the causes and mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the aging of the global population and changes in lifestyle, diabetes mellitus (DM) has become a major challenge in public health1,2. About 537 million adults (20–79 years) worldwide have diabetes, and this figure is expected to rise to 783 million by 20453. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common form, accounting for nearly 90% of all diabetes cases globally1. More seriously, many T2DM patients suffer from multimorbidity4, which means the co-existence of two or more diseases in an individual5. Compared to individuals with a single disease, those with multimorbidity often experience a poorer quality of life6,7,8, accelerated functional decline9, higher healthcare costs10,11,12, and more complicated diagnosis and treatment13. This situation not only impacts patients but also imposes a significant burden on society14. Unfortunately, current healthcare systems and public health policies are predominantly focused on addressing individual diseases, which often result in fragmented and sometimes contradictory care for people with multimorbidity5,15. This limitation underscores the need for a more integrated and comprehensive understanding of the complex networks and interrelationships behind multimorbidities to inform the development of more effective and coordinated clinical treatment and management strategies.

Previous studies on multimorbidity have primarily focused on investigating the prevalence rates or analyzing various socio-demographic factors, as well as using simple cluster analyses to discover common diseases combinations16,17,18,19,20. These approaches are insufficient for systematically revealing the underlying patterns and deeper relationships between multimorbidity. In recent years, the Association Rule Mining (ARM) technique, as an effective tool for discovering significant associations between variables in large-scale datasets, has been widely used in the field of multimorbidity research. This is because it is able to mine the hidden associative relationships between complex comorbidities and has the advantage of being higher interpretability than the currently popular and more advanced deep learning21. However, most studies have been conducted on middle-aged and older adults in the general population15,22,23,24,25,26; research applying ARM in T2DM population is relatively limited. However, T2DM patients have a higher prevalence of multimorbidity compared to the general population27,28. Studies have reported that the multimorbidity prevalence among middle-aged and elderly T2DM outpatients is 83.3%29, and among hospitalized T2DM patients, it reaches 95.6%4. Additionally, people with diabetes have a higher incidence and severity of certain comorbidities due to exposure to elevated glucose and insulin resistance28,30. Therefore, it is essential to employ ARM to specifically mine the multimorbidity patterns in T2DM. Currently, only a handful of studies have employed ARM method to analyze the multimorbidity profile for T2DM patients4,29,31. Although these studies have large sample sizes, they either focused only on patterns of association between other diseases and DM, ignoring the relationship between comorbidities4, or the studies did not include typical complications of T2DM, which are highly prevalent in this population31,32. These limitations highlight the need for more comprehensive and in-depth multimorbidity pattern mining studies in T2DM patients, especially analyzing the multimorbidity characteristics by incorporating typical complications.

This study aims to investigate the current status and influencing factors of multimorbidity, including typical complications, in patients with T2DM, with a focus on mining frequent disease combination patterns and strong association rules. The findings of this study can be used to guide clinicians in the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity in T2DM patients, and to suggest possible directions for further research into the etiology and mechanisms of multimorbidity.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study population

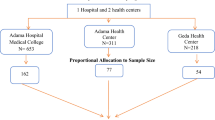

Data were extracted from all 6,951 diabetic inpatients admitted to the Department of Endocrinology at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University between January 1, 2021, and March 28, 2024. The dataset included basic demographic information (e.g., gender, age, height, weight, and marital status) and discharge diagnosis details. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with T2DM; (2) age ≥ 18 years. Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients with type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes, or other types of diabetes; (2) patients with missing key information such as height, weight, gender, marital status. Based on these criteria, 5,838 patients with type 2 diabetes were included in the analysis.

Defining multimorbidity

Multimorbidity is defined as the co-existence of two or more diseases (except type 2 diabetes) in a single T2DM individual. The diseases included in the multimorbidity discussed in this study encompass both typical complications of T2DM and other common comorbidities. Whereas previous studies have primarily focused on common comorbidities, with less emphasis on typical complications, this study aims to address this gap. Typical complications are those directly caused by T2DM, such as acute metabolic, microvascular, and cardiovascular conditions. Common comorbidities refer to other conditions that co-occur in individuals with diabetes, including incidental conditions and those related to diabetes but not traditionally classified as typical complications28,30. Based on the most frequently included diseases in previous studies4,24,25,33,34,35 and the prevalent typical complications associated with T2DM, we extracted information about complications and comorbidities from discharge diagnoses. Ultimately, 26 diseases with a prevalence greater than 1% in the study dataset were included in the multimorbidity analysis. These diseases encompass 9 typical complications: diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), diabetic peripheral vascular disease (DPVD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), diabetic foot (DF), diabetic nephropathy (DN), diabetic ketosis (DK), diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), coronary atherosclerotic heart disease (CAHD), cerebral infarction (CI); as well as 17 comorbidities: hypertension, anxiety or depression (ANX/DEP), thyroid disease (TD), lumbar or cervical spondylosis (LS/CS), fatty liver (FL), osteoporosis, sleep disorders (SD), tumor, arthropathy, gastritis, cataracts, gallbladder polyp (GP), hyperuricemia, anemia, hepatitis, lithiasis, hyperlipidemia.

Category criteria

Based on existing literature related to the analysis of influencing factors in multimorbidity, combined with the availability of data, we select gender, age, BMI, and marital status as the categorical variables in this study22,36,37. Patients were categorized into different subgroups based on gender and marital status. They were also divided into four age groups: 18 to 44 years, 45 to 54 years, 55 to 64 years, and 65 years and older31. Additionally, patients were classified into four groups based on body mass index (BMI): a BMI between 18.5 and 24 is considered normal, a BMI below 18.5 indicates underweight, a BMI between 24 and 28 is classified as overweight, and a BMI above 28 is categorized as obese22.

Association rule mining

ARM is a data mining technique originally developed in marketing research to explore sets of items that consumers frequently purchase together38. It can uncover hidden information and interesting patterns in large dataset39. In this study, the Apriori algorithm40,41 was used to mine frequent disease combination patterns and association rules for complications and other diseases in T2DM. As a well-established algorithm grounded in prior probabilities, Apriori leverages knowledge of frequent itemsets while iteratively searching through the dataset to identify all frequent itemsets, thereby uncovering potential associations42. By applying association rules to analysis multimorbidity in T2DM, we can investigate patterns of disease co-occurrence and reveal underlying relationships among them. The algorithm generates a set of diseases that exhibit strong association rules by utilizing various evaluation metrics.

The association rules between diseases are expressed in the form of A→B, where A is referred to as the antecedent and B as the consequent21. Support, confidence, and lift are the three most important metrics that used to evaluate the effectiveness of the association rule between A and B33. Support measures the probability of disease A and B co-occurring in the whole dataset D, with the formula: support(A→B) = P(A∩B) = count(A∩B)/count(D), and the result is expressed as a percentage21,33. In this study, support refers to the proportion of patients who simultaneously suffer from both disease A and disease B. A higher support value indicates a greater likelihood of disease A and B occurring together. Confidence refers to the conditional probability of B occurring given that A has already occurred. It is calculated as: confidence(A→B) = P (A∩B)/P(A) = P(B|A)33. In this study, confidence refers to the proportion of people with disease A who also have disease B. Higher confidence values suggest that B is more likely to occur once A is occurred. Lift measures how many times more likely B is to occur in the presence of A compared to the unconditional probability of B. It is calculated as: Lift(A→B) = P(B|A)/P(B)33. A lift greater than 1 indicates a strong positive correlation between disease A and B. The higher the lift, the stronger the correlation. If the lift equals 1, it suggests no association between A and B.

In the definition of the above association rules, A and B can be either single diseases or combinations of diseases. Given the significant differences in the baseline prevalence of various diseases, lift was considered as the most important evaluation metric in this study. We should pay particular attention to the fact that the association rule between diseases A and B does not indicate a causal relationship between them.

Statistical analysis

In this study statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0 to examine 26 included diseases. Grouping factors such as gender, age, BMI, and marital status were included for stratified analysis. Prevalence of single diseases and multimorbidity across different groups were compared using either the Chi-square test or the Cochran-Armitage trend test, Bonferroni method was used for multiple testing adjustment. Multivariate logistic regression was employed to examine the relationships between various factors and multimorbidity. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To identify the association patterns and strength between different diseases, data mining was performed using the mlxtend package in Python 3.8, which applies the Apriori algorithm for association rule mining. Finally, the discovered binary comorbidity patterns were visualized through a network graph, in which diseases were represented as nodes, and the size of each node reflected the prevalence of the corresponding disease. The edges between nodes represent the comorbidity relationship between the two diseases, and the weight of the edges represents the comorbidity rate also known as support.

Ethical statement

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Medical University (Approval number: HYLL-2021-388). Ethics Committee of Hainan Medical University waived the need for informed consent because the data had been deidentified. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 5,838 inpatients with T2DM were included in this analysis. Among these patients, 3,514 (60.2%) were male, and 2,324 (39.8%) were female. Regarding age distribution, 12.4% were aged 18–44 years, 19.8% were aged 45–54 years, 33.1% were aged 55–64 years, and 34.7% were aged 65 years and older. The proportion of patients in different BMI categories was 6.3% for lean, 52.7% for normal, 29.8% for overweight, and 11.2% for obese. Additionally, 93.3% of the patients were married (Table 1).

Prevalence and influencing factors of single diseases

Among the 26 diseases included in the analysis, the five with the highest prevalence were DPN, DPVD, hypertension, FL, and DN (Fig. 1). The prevalence of 26 diseases showed differences between genders (Fig. 2). The results of the univariate analysis demonstrate significant differences in the prevalence of various complications and chronic diseases among different groups (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The Cochran-Armitage trend test showed an overall increasing trend in the prevalence of DPN, DPVD, hypertension, DN, CI, lithiasis, DR, DF, and anemia with increasing age (P < 0.05), while there was a decreasing trend in the prevalence of FL (P < 0.05). In addition, of the 26 diseases included in this study, 18 showed significant differences in prevalence between genders (P < 0.05). The prevalence of DPN, hypertension, CI, anemia, ANX/DEP, LS/CS, and osteoporosis was higher in females than in males. Conversely, the prevalence of DN, lithiasis, hyperuricemia, and DF was lower in females than in males. Furthermore, the Cochran-Armitage trend test also revealed a linear trend in the prevalence of DPN, DPVD, hypertension, FL, CI, hyperlipidemia, DR, DF, and anemia across different BMI categories(P < 0.05). However, among the different marital status groups, only DPN, DPVD, hypertension, CI, and lithiasis showed differences in prevalence (P < 0.05).

The prevalence of 26 diseases in study population. DPN, diabetic peripheral neuropathy; DPVD, diabetic peripheral vascular disease; DR, diabetic retinopathy; DF, diabetic foot; FL, fatty liver; DN, diabetic nephropathy; DK, diabetic ketosis; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; GP, gallbladder polyp; CAHD, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease; CI, cerebral infarction; SD, sleep disorders; ANX/DEP, anxiety or depression; TD, thyroid disease; LS/CS, lumbar or cervical spondylosis.

Comparison of the prevalence of 26 diseases between males and females. DPN, diabetic peripheral neuropathy; DPVD, diabetic peripheral vascular disease; DR, diabetic retinopathy; DF, diabetic foot; FL, fatty liver; DN, diabetic nephropathy; DK, diabetic ketosis; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; GP, gallbladder polyp; CAHD, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease; CI, cerebral infarction; SD, sleep disorders; ANX/DEP, anxiety or depression; TD, thyroid disease; LS/CS, lumbar or cervical spondylosis.

Current status of multimorbidity

The distribution of multimorbidity in T2DM is summarized in Table 2 and illustrated Fig. 3. It can be seen that a total of 5,711 patients (97.8%) suffered from multimorbidity, only 0.3% of the study population did not have any of the 26 diseases included, and up to 79.6% of the patients suffered from four or more diseases. The total number of diseases present in any individual ranged from 0 to 12, with the highest number of individuals suffering from 5 diseases (20.6%) and those suffering from 12 diseases comprising 0.1% of the total population. In addition, it was found that the prevalence of multimorbidity was significantly higher in males than in females (χ²=4.399, P < 0.05) and tended to increase with age (Cochran-Armitage χ²=118.664, P < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of multimorbidity among people with different BMI or marital status (P > 0.05). Multivariable logistic regression analysis indicated that males exhibited a significantly higher risk of multimorbidity compared to females (OR = 2.094, 95% CI: 1.451–3.020). The risk of multimorbidity was higher in the 45 ~ 54, 55 ~ 64, and 65 years or older age groups compared to the 18 ~ 44 years old reference group, with odds ratios of 5.287 (95% CI: 3.207–8.717), 6.215 (95% CI: 4.002–9.652), and 22.478 (95% CI: 11.374–44.422), respectively.

Analysis of multimorbidity patterns

By setting the minimum support at 0.03, we identified all the frequent disease combination patterns. Among all combinations, the top three binary combinations with the highest support were DPN + DPVD(74.1%), DPN + hypertension(43.3%), and DPVD + hypertension(41.5%). This indicates that 74.1% of T2DM patients in the study population also suffered from both DPN and DPVD; 43.3% of T2DM patients suffered from both DPN and hypertension; and 41.5% of T2DM patients suffered from both DPVD and hypertension. The top three ternary combinations with the highest support were DPN + DPVD + hypertension(39.2%), DPN + DPVD + CI(29.0%), and DPN + DPVD + DN(27.3%). Almost all disease combination patterns contained typical complications of T2DM. In addition, among all disease combinations, those with a prevalence exceeding 3% contained a maximum of five diseases. Furthermore, the top three binary and ternary disease combinations identified by gender were similar to those in the overall population, with comparable support levels. However, the patterns of disease combination observed in different age groups differed from those in the whole population, and the support of major disease combinations tended to increase with age (see Supplementary Tables 2 and Supplementary Table 3).

In order to provide a comprehensive picture of all binary disease combination patterns, we used a network diagram for visualization. Figure 4 shows the network graph for the entire study population, while Fig. 5 displays the network graph for males and females respectively. The network diagram enables us to visually compare the prevalence of each single disease as well as all binary disease combination patterns and their support. If there is an edge between two diseases in the graph, it means that the probability of coexistence of these two diseases is greater than 0.03, and the thicker the edge, the higher the probability of coexistence. As can be seen from the figure, DPN, DPVD and hypertension are comorbidly associated with almost all diseases, and the comorbidity networks differ considerably between males and females. Supplementary Fig. 1 displays a graph of the binary comorbidity network for different age groups. As shown in the figure, the number of diseases with support greater than 0.03 increases with age, and the comorbidity network becomes more complex with age. Supplementary Fig. 2 presents the binary comorbidity network diagrams for the various BMI groups. As can be seen from the figure, the lean group had the least comorbidities, and the binary comorbidity relationship was more complex with increasing BMI.

Binary comorbidity network diagram of the study population. The size of the nodes (circle containing the morbidity name) is proportional to the prevalence of the disease, and the width of edges connecting the nodes is determined by the support of the two diseases connected by the edge. (minimum support = 0.03). DPN, diabetic peripheral neuropathy; DPVD, diabetic peripheral vascular disease; DR, diabetic retinopathy; DF, diabetic foot; FL, fatty liver; DN, diabetic nephropathy; DK, diabetic ketosis; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; GP, gallbladder polyp; CAHD, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease; CI, cerebral infarction; SD, sleep disorders; ANX/DEP, anxiety or depression; TD, thyroid disease; LS/CS, lumbar or cervical spondylosis.

Binary comorbidity network diagram for males and females. Node size is according to the prevalence of the disease, and the width of edges connecting the nodes is determined by the support of the two diseases connected by the edge.(minimum support = 0.03). DPN, diabetic peripheral neuropathy; DPVD, diabetic peripheral vascular disease; DR, diabetic retinopathy; DF, diabetic foot; FL, fatty liver; DN, diabetic nephropathy; DK, diabetic ketosis; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; GP, gallbladder polyp; CAHD, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease; CI, cerebral infarction; SD, sleep disorders; ANX/DEP, anxiety or depression; TD, thyroid disease; LS/CS, lumbar or cervical spondylosis.

Analysis of association rules

There is no universally fixed standard for setting threshold values in association rule mining. Based on relevant literature in the field of multimorbidity association mining, support thresholds are typically set between 0.01 and 0.03, confidence thresholds range from 10 to 50%, and lift thresholds are generally between 1 and 1.522,29,33,43. In this paper, the thresholds are set with reference to previous similar studies and adjusted with data characteristics. Through experiments, we found that rules with smaller support cover too few cases, which may lead to chance associations, while smaller confidence thresholds are prone to contain inverse relationships. We gradually increased the thresholds by trial-and-error method until the rules could be reasonably interpreted. We conducted several rounds of manual tuning and ultimately set the support threshold to 0.1, the minimum confidence level to 45%, and the lift to 1.2. The association rules were limited to include 2 or 3 diseases, with the consequent part restricted to a single disease. Across the study population, 13 association rules were identified that satisfied the set criteria (Table 3). Among these, 4 rules were binary patterns, while the remaining 9 were ternary patterns. The 13 association rules are centered around only 7 diseases: DPVD, DPN, hypertension, DN, FL, hyperlipidemia, and CI. The consequent items in the 13 rules included 4 diseases, with 6 rules pointing to hypertension, 3 to DN, 3 to FL and 1 to CI. The association rule {DPVD + DN}→{Hypertension} (support: 19.2%, confidence: 66.6%, lift:1.43) is identified as the strongest. This association rule revealed that 19.2% of the study population suffered from DPVD, DN, and hypertension simultaneously. Furthermore, among individuals with both DPVD and DN, 66.6% also had hypertension, which was 1.43 times more likely than hypertension rate in the study population.

Due to differences in comorbidity patterns among different gender, age, and BMI groups, we conducted association rule mining for each subgroup separately, resulting in 24, 23, and 50 association rules, respectively. Given the large number of rules, we increased the lift threshold to 1.30, ultimately retaining 14 gender-related, 15 age-related (as shown in Tables 4 and 5), and 36 BMI-related association rules (Table 6). Among the 14 gender-related association rules, the rule {DPVD + DN}→{Hypertension} demonstrated the highest confidence and lift in both male and female groups. The number of association rules obtained in women was less than in men. In the consequent of association rules, males are only associated with hypertension, DN, and FL, while females are only linked to hypertension and CI. Of the 15 association rules related to age group, the most rules pointed to hypertension and DN, and no association rules met the established criteria in the group aged 65 and above. Association rules in different BMI group exhibited more diversity, but still the highest number of rules pointed to hypertension.

In summary, of the association rules identified, most had hypertension as the consequent. In association rules pointing to hypertension, the antecedent almost always contained DN. In all association rules pointing to CI, the antecedent almost always contained hypertension. Association rules with DPVD as a consequent were only identified in the obese group, and their antecedents often included CI. The association rule {DR}→{DN} was only identified in the age subgroups and the lifts were all higher than 2.

Discussion

The number of individuals with T2DM is substantial, and their multimorbidity prevalence and severity of co-morbidities are more severe than those of the general population. Therefore, a specialized study in the current status of multimorbidity, its influencing factors, frequent disease combination patterns, and associations rules in T2DM patients is essential for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies. Currently, there are no specific recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of multimorbidity in T2DM patients4. To our knowledge, this study is the first to define multimorbidity in diabetic patients by integrating multiple typical complications and chronic diseases and simultaneously using the ARM approach to mine the association rules among multimorbidity. Previous studies on the association rules of multimorbidity in diabetic patients have often failed to include typical complications, resulting in an incomplete understanding of the disease patterns. This study addresses this gap by including typical complications in diabetic patients for multimorbidity analysis and is a good addition to the existing literature.

The results of the single disease prevalence showed that three of the top five diseases in terms of prevalence were typical complications, each with high prevalence rates. This highlights the necessity for a study specifically focused on T2DM and the importance of including typical complications. Additionally, multiple diseases, such as DPN, hypertension, and DN, exhibited significant differences across gender, age, and BMI categories, emphasizing the need for stratified analysis.

Our investigation reveals that 97.8% of hospitalized T2DM patients suffered from multimorbidity, exceeding the 95.6% and 83.3% reported in previous studies4,29. This discrepancy is mainly due to differences in the range of diseases included in the definition of multimorbidity and the source of data. The prevalence of multimorbidity is highly dependent on the population setting and the number and types of diseases included in the definition30. In previous studies, multimorbidity was mainly limited to chronic diseases and rarely included typical complications, whereas complications are very common in patients with T2DM. Furthermore, our study population was drawn from inpatients at a well-known tertiary hospitals in provincial capital, meaning these patients here tend to be sicker and thus more likely to have multimorbidity. However, multiple studies have consistently shown a high prevalence of multimorbidity in patients with T2DM. This suggests that the situation is very serious, and the patterns of multimorbidity need to be identifiedd to enable targeted interventions.

Our study revealed a higher prevalence of multimorbidity among men compared to women, which aligns with the findings of Zou et al.18 and Wang et al.43. This gender disparity may be due to the significantly lower prevalence of smoking and alcohol consumption among Chinese women, both of which are recognised risk factors for various diseases25,44,45. However, numerous previous studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence of multimorbidity in women15,19,20,33,37. The reason for this discrepancy may be that previous studies have focused on middle-aged and older adults, whereas during menopause, oestrogen levels decline in women, which may increase their susceptibility to a variety of health problems46. Additionally, the study also showed an increasing trend in the prevalence of multimorbidity with age, which has been reported in many previous studies4,5,16,47,48. This may be due to age-related cellular degeneration, decreased immune function, oxidative stress, and inflammatory processes18. However, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of multimorbidity between different BMI or marital status groups, which is inconsistent with some studies22,37. Possible reasons for this discrepancy include the severely imbalanced data on marital status in the study population, with the non-married group being too small to be representative. In addition, the lack of consideration for the interaction between gender and BMI might have obscured differences in multimorbidity across various BMI categories49, suggesting a need for more detailed subgroup analyses in future research.

The binary comorbidity network graph demonstrates differences in comorbid relationships between men and women. Compared with women, men exhibit more complex commorbidity patterns. This may be because men in China typically engage in more adverse health behaviors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, than women. Additionally, women in Hainan region have higher levels of physical activity than men; regular exercise can improve insulin sensitivity50, thereby reduce diabetes complications. The probability of disease coexistence and the complexity of the comorbidity network increase with age, consistent with the findings in the univariate and multivariate analyses. Although no significant differences in the prevalence of comorbidity across different BMI groups were observed in both univariate and multivariate analyses, the binary network diagram suggests that comorbidity relationships tend to become more complex with increasing BMI, consistent with prior research. A study from Finnish cohort identified obesity as a risk factor for 21 distinct cardiometabolic, digestive, respiratory, neurological, musculoskeletal, and infectious diseases, underscoring its importance in multimorbidity prevention51. Additionally, overweight individuals have a 1.32 times higher risk of multimorbidity compared to those with normal BMI, while obese individuals face a 1.93 times increased risk. Furthermore, obese individuals were 1.75 times more likely to develop multimorbidity than non-obese individuals52. These findings highlight obesity as a critical factor in the development and management of multimorbidity among T2DM patients.

The results of frequent comorbidity patterns mined using the ARM method demonstrate that almost all frequent comorbidity combinations include complications, and many of the comorbidity combinations with high support values consist solely of complications. This indicates that the multimorbidity patterns in T2DM are primarily centered around its typical complications, emphasizing the critical role of complications in the analysis of multimorbidity in T2DM patients. Therefore, the analysis of multimorbidity in the T2DM population cannot overlook the consideration of complications. Among all frequent comorbidity combinations, {DPVD + DPN} has the highest support (74.1%), indicating the highest likelihood of this comorbidity combination occurring. The frequent comorbidity relationship between DPN and DPVD represents a novel discovery, as there have been no prior reports documenting their high-frequency co-occurrence, and research exploring the causal relationship and underlying mechanisms between these two conditions remains limited. Notably, in a machine-learning prediction study focusing on DPN, DPVD was identified as a significant predictor53. Therefore, individuals diagnosed with either DPN or DPVD should implement preventive measures to mitigate the occurrence of the other condition.

The identified association rules indicate that a significant majority of the rules had hypertension as the consequent. For example, a variety of diseases and disease combinations including DN, CI, DPVD + DN and DN + DPN, were associated with hypertension. This is consistent with previous studies, which have also noted that comorbidity patterns often revolve around hypertension29,43,54. This suggests that individuals with the aforementioned diseases should pay close attention to the risk of hypertension. Additionally, in the association rules pointing to hypertension, DN is almost always an antecedent. However, this does not mean that DN is the cause of hypertension, as association rule does not imply causation. Some studies have highlighted that DN may play a significant role in the development of hypertension in patients with diabetes55. This association might be linked to endothelial dysfunction caused by diabetes. In diabetic patients, insulin resistance and insufficient insulin secretion lead to reduced responsiveness of endothelial cells to insulin, which in turn affects vascular relaxation, increases vascular resistance, and ultimately results in elevated blood pressure56,57. The specific causal mechanism between DN and hypertension can be further clarified by referring to the methodology of Chen et al.58.

We found that hypertension was consistently identified as an antecedent in all association rules pointing to CI. Hypertension is widely proven to be a risk factor for cerebral infarction, and the higher the blood pressure, the greater the risk of CI59. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral vasculature lead to CI mainly through the mechanisms of atherosclerosis, aneurysm rupture, and microaneurysm rupture. Managing hypertension can significantly reduce the risk of cerebral infarction60. This finding suggests that clinicians should pay particularly close attention to the risk of CI in diabetic patients with hypertension, and should monitor blood pressure regularly and take appropriate therapeutic measures.

Association rules with DPVD as the consequent are identified exclusively in obese populations, and their antecedents frequently include CI, with the confidence level for these rules consistently exceeding 90%. This is because obese diabetic patients frequently present hypertension and dyslipidemia, which are primary risk factors for CI and DPVD61. Furthermore, persistent hyperglycemia impairs vascular endothelial cells, fostering atherosclerosis and elevating the risk of both CI and DPVD62. Obese diabetics often exhibit chronic inflammatory states, which release multiple inflammatory mediators that exacerbate atherosclerosis and vascular pathologies, thereby increasing the risk of CI and DPVD63. This finding has important clinical implications for risk assessment and early intervention, highlighting the need for enhanced vascular health monitoring and treatment strategies for obese diabetic patients.

All identified association rules pointing to FL have hyperlipidemia as a constituent in their antecedents. Hyperlipidemia can promote the occurrence and progression of FL. When the level of lipids in the blood is excessively high, excess lipids can be deposited in the liver, leading to FL. Conversely, FL can also exacerbate hyperlipidemia. Patients with FL often have impaired liver function, possibly making it difficult to effectively clear lipids from the blood, thereby further elevating blood lipid levels64. This indicates that individuals with T2DM, while suffering from hyperlipidemia, should pay special attention to whether they already have FL and whether there are risk factors for developing FL. Taking preventive measures in advance to ensure timely treatment for the patients.

This association rule {DR}→{DN} has the highest lift of all the rules identified, more than 2. This rule suggests that patients with DR are more than twice as likely to have DN as those general T2DM patient. Epidemiologic studies have shown that DN and DR are closely related in diabetic patients. The probability of DN in patients with DR is three times higher than in patients without DR65; therefore, DR patients should be closely monitored for the presence of DN.

No meaningful association rules were mined in the age group above 65 years old, which may be due to the fact that this age group has the largest number of people and the most complex comorbidity relationships, while we limited the maximum number of diseases in each rule to three during the mining process, which resulted in the failure to identify meaningful association rules from the complex comorbidity relationships. However, the results of association rule mining revealed differences in comorbidity patterns and identified association rules among type 2 diabetes patients of different gender, age, and BMI subgroups. This finding suggests that gender, age, and BMI should be fully considered when addressing the multimorbidity problem of T2DM, thereby enabling the development of targeted treatment and management strategies.

This study has a large sample size and a wide range of diseases included, especially the inclusion of typical complications, thus providing a good representation of the multimorbidity status and patterns of T2DM patients. Despite the high prevalence of multimorbidity in the T2DM population, there are no specific guidelines for its diagnosis and treatment66. The study has uncovered several novel findings regarding the relationships between comorbidities. However, further longitudinal or laboratory studies are required to clarify the causality and clinical significance, ultimately improving the prevention and treatment of multimorbidities in diabetic patients.

Several limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. First, our study data came from inpatients in a tertiary hospital, where patients may be sicker and have a wider variety of comorbidities, so the prevalence of multimorbidity and the association rules mined may not be applicable to the entire diabetic population. However, our results based on more severe cases may provide ideas for research into the early prevention of multimorbidity in T2DM. Future studies could use data from T2DM patients at multi-level medical institutions or integrate data from populations of different severities using Meta-analysis67 to clarify the generalizability of this study’s findings. Second, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, the temporal dynamics of co-morbidities cannot be fully captured. Consequently, the identified association rule do not indicate a causal link between the antecedent and consequent items. However, our findings provide valuable insights for further etiopathogenic and pathophysiological investigations. In future research, longitudinal studies could be conducted to track the temporal evolution of co-morbidities and elucidate the causal sequence. Additionally, integrating methodologies such as randomized controlled trials or prospective cohort studies may help to validate whether the association rule is causal associations. Third, due to insufficient data availability, detailed information about patients’ physical activity, smoking and drinking habits, socioeconomic status and duration of diabetes, which has been reported to be associated with multimorbidity, was not included in this study20,36,50,68. Finally, due to the lack of a standardized criterion for threshold settings in association rule mining, different threshold settings may identify different strong association rules, implying that our study may have overlooked some meaningful rules.

Conclusion

This study found that the prevalence of multimorbidity in inpatient T2DM was very high, and multimorbidity varies significantly across gender and age groups. The ARM method is an effective way to mine frequent disease combination patterns and association rules. The mining results revealed that the comorbidity patterns of diabetic patients mainly centered around typical complications; the frequent co-morbidity combination of DPN + DPVD is a novel finding; disease combination patterns and association rules varied across gender, age, and BMI. Healthcare professionals can utilize these findings to develop targeted screening and treatment strategies for the multimorbidity of diabetes. Researchers can use the association rules to explore the causality and mechanisms of comorbidities. Further research should consider incorporating more influencing factors in a wider T2DM population and analyzing the interaction effects between factors to obtain more comprehensive results, ultimately reducing the adverse consequences and disease burden of multimorbidity on individuals, families, and society.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmad, E. et al. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 400, 1803–1820 (2022).

Lv, K. et al. Detection of diabetic patients in people with normal fasting glucose using machine learning. BMC Med. 21, 342 (2023).

Sun, H. et al. Idf diabetes atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 183, 109119 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. The diabetes mellitus Multimorbidity network in hospitalized patients over 50 years of age in china: data mining of medical records. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1433 (2024).

Skou, S. T. et al. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 8, 48 (2022).

Fortin, M. et al. Relationship between Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life of patients in primary care. Qual. Life Res. 15, 83–91 (2006).

Bao, X. Y. et al. The association between Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional survey among community middle-aged and elderly residents in Southern China. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 17, 107 (2019).

Makovski, T. T. et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 53, 100903 (2019).

Pati, S. et al. Prevalence and outcomes of Multimorbidity in South asia: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 5, e007235 (2015).

Lehnert, T. et al. Review: health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Med. Care Res. Rev. 68, 387–420 (2011).

McPhail, S. M. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag Healthc. Policy. 9, 143–156 (2016).

Picco, L. et al. Economic burden of Multimorbidity among older adults: impact on healthcare and societal costs. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16, 173 (2016).

Asogwa, O. A. et al. Multimorbidity of non-communicable diseases in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 12, e049133 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Physical multimorbidity, health service use, and catastrophic health expenditure by socioeconomic groups in china: an analysis of population-based panel data. Lancet Glob Health. 8, e840–e849 (2020).

Hernandez, B., Reilly, R. B. & Kenny, R. A. Investigation of Multimorbidity and prevalent disease combinations in older Irish adults using network analysis and association rules. Sci. Rep. 9, 14567 (2019).

Barnett, K. et al. Epidemiology of Multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 380, 37–43 (2012).

Stanley, J. et al. Epidemiology of Multimorbidity in new zealand: A cross-sectional study using national-level hospital and pharmaceutical data. BMJ Open 8,e021689 (2018).

Zou, S. et al. Prevalence and associated socioeconomic factors of Multimorbidity in 10 regions of china: an analysis of 0.5 million adults. J. Public. Health (Oxf). 44, 36–50 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Age- and sex-specific differences in Multimorbidity patterns and Temporal trends on assessing hospital discharge records in Southwest china: Network-based study. Journal Med. Internet Research 24,e27146 (2022).

Yao, S. S. et al. Prevalence and patterns of Multimorbidity in a nationally representative sample of older chinese: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 1974–1980 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. A data mining algorithm for association rules with chronic disease constraints. Comput Intell Neurosci 8526256 (2022). (2022).

Yu, Z. et al. Identification of status quo and association rules for chronic comorbidity among Chinese middle-aged and older adults rural residents. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1186248 (2023).

Tran, T. N. et al. Multimorbidity patterns by health-related quality of life status in older adults: an association rules and network analysis utilizing the Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Epidemiol. Health. 44, e2022113 (2022).

Zheng, Z. et al. Association rules analysis on patterns of Multimorbidity in adults: based on the National health and nutrition examination surveys database. BMJ Open. 12, e063660 (2022).

Roh, E. H. Analysis of multiple chronic disease characteristics in South Koreans by age groups using association rules analysis. Health Inf. J. 28, 14604582211070208 (2022).

Lee, Y. et al. Patterns of Multimorbidity in adults: an association rules analysis using the Korea health panel. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17, 2618 (2020).

Alonso-Morán, E. et al. Multimorbidity in people with type 2 diabetes in the Basque country (spain): prevalence, comorbidity clusters and comparison with other chronic patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 26, 197–202 (2015).

Cicek, M. et al. Characterizing Multimorbidity from type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 50, 531–558 (2021).

Yan, Z., Gao, R., Sun, M. & Chen D. Patterns of Multimorbidity in middle-aged and elderly type 2 diabetes patients: an electronic outpatient medical record-based analysis. Chin. J. Public. Health. 38, 1576–1581 (2022).

Khunti, K. et al. Diabetes and multiple long-term conditions: A review of our current global health challenge. Diabetes Care. 46, 2092–2101 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Epidemiological status and characteristics of common comorbidities of type 2 diabetes mellitus among 1.15 million patients in Beijing area. J. Third Military Med. Univ. 43, 1126–1132 (2021).

Tan, K. R. et al. Evaluation of machine learning methods developed for prediction of diabetes complications: A systematic review. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 17, 474–489 (2023).

Huang, Y. et al. Analysis of multiple chronic disease characteristics in middle-aged and elderly South Koreans by exercise habits based on association rules mining algorithm. BMC Public. Health. 23, 1232 (2023).

Chua, Y. P. et al. Definitions and prevalence of Multimorbidity in large database studies: A scoping review. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18, 1673 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Associations among multimorbid conditions in hospitalized middle-aged and older adults in china: statistical analysis of medical records. JMIR Public. Health Surveillance 8, e38182 (2022).

Ni, W. et al. Sociodemographic and lifestyle determinants of Multimorbidity among community-dwelling older adults: findings from 346,760 share participants. BMC Geriatrics 23, 419 (2023).

Lin, W. Q. et al. Prevalence and patterns of Multimorbidity in chronic diseases in guangzhou, china: A data mining study in the residents’ health records system among 31 708 community-dwelling elderly people. BMJ Open 12, e056135 (2022).

Dhanabhakyam, M. & Punithavalli, M. A survey on data mining algorithm for market basket analysis. Global J. Comput. Sci. Technology 11, 22–28 (2011).

Borgelt, C. Frequent item set mining. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2, 437–456 (2012).

Agrawal, R. & Srikant, R. in Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases.

Nagwan, S. et al. Mining medical data for identifying frequently occuring diseases by using apriori algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 131, 18–20 (2015).

Wei, Y., Yang, R. & Liu, P. y. in 2009 IEEE International Symposium on IT in Medicine & Education. 942–946.

Wang, Z. et al. Multimorbidity status and risk factors among adults aged 45–64 years in 15 provinces of China in 2018: based on association rule analysis. J. Environ. Occup. Med. 41, 768–773 (2024).

Brath, H. et al. [smoking, heated tobacco products, alcohol and diabetes mellitus (update 2023)]. Wien Klin. Wochenschr. 135, 84–90 (2023).

Jensen, H. A. R. et al. Trends in social inequality in mortality in Denmark 1995–2019: the contribution of smoking- and alcohol-related deaths. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 78, 18–24 (2023).

Xu, X., Jones, M. & Mishra, G. D. Age at natural menopause and development of chronic conditions and multimorbidity: results from an Australian prospective cohort. Hum. Reprod. 35, 203–211 (2020).

Aminisani, N. et al. Socio-demographic and lifestyle factors associated with Multimorbidity in new Zealand. Epidemiol. Health. 42, e2020001 (2020).

Geng, Y. et al. Prevalence and patterns of Multimorbidity among adults aged 18 years and older - china, 2018. China CDC Wkly. 5, 35–39 (2023).

Koceva, A. et al. Sex- and gender-related differences in obesity: from pathophysiological mechanisms to clinical implications. International J. Mol. Sciences 25, 7342 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Exploration of physical activity, sedentary behavior and insulin level among short sleepers. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1371682 (2024).

Kivimäki, M. et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: an observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10, 253–263 (2022).

Shan, J., Yin, R. & Panuthai, S. Body mass index and Multimorbidity risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 123, 105418 (2024).

Luo, L. et al. Development and validation of a risk nomogram model for predicting peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Frontiers Endocrinology 15, 1338167 (2024).

Hu, Y. et al. Prevalence and patterns of Multimorbidity in China during 2002–2022: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 93, 102165 (2024).

Epstein, M. & Sowers, J. R. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Hypertension 19, 403–418 (1992).

Jia, G. & Sowers, J. R. Hypertension in diabetes: an update of basic mechanisms and clinical disease. Hypertension 78, 1197–1205 (2021).

Mahler, R. J. Diabetes and hypertension. Horm. Metab. Res. 22, 599–607 (1990).

Chen, Y. et al. Comment on: predictive value of pretreatment Circulating inflammatory response markers in the neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer: Meta-analysis. Br J. Surg 111, znae187 (2024).

Tanahashi, N. [management of blood pressure for stroke prevention]. Nihon Rinsho Japanese J. Clin. Med. 74 (4), 681–689 (2016).

Phillips, S. J. & Whisnant, J. P. Hypertension and the brain. Arch. Intern. Med. 152, 938–945 (1992).

Simpkins, A. N., Neeland, I. J. & Lavie, C. J. Tipping the scales for older adults: time to consider body fat assessment and management for optimal atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and stroke prevention? J. Am. Heart Association. 10, e021307 (2021).

Li-n, W. The effects of acute hyperglycaemia and excess dietary glucose on cardiovascular function. Chinese Foreign Med. Research (2011).

Rohm, T. V. et al. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 55, 31–55 (2022).

Lu, M., Cheng, Z. & Chang B.Analysis of the prevalence rate and the related factors of glycemia, hyperlipemia and fatty liver. Chinese journal of Clinical nutrition. (2002).

Xu, Y. & Xiang, Z. E, W. et al. Single-cell transcriptomes reveal a molecular link between diabetic kidney and retinal lesions. Communications Biology 6, 912 (2023).

Gao, N. et al. Prevalence of chd-related metabolic comorbidity of diabetes mellitus in Northern Chinese adults: the reaction study. J. Diabetes Complications. 30, 199–205 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Systematic and meta-based evaluation on job satisfaction of village doctors: an urgent need for solution issue. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 856379 (2022).

Ashworth, M. et al. Journey to multimorbidity: longitudinal analysis exploring cardiovascular risk factors and sociodemographic determinants in an urban setting. BMJ Open. 9, e031649 (2019).

Funding

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province(Nos. 821QN0895 and 821MS044).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study conception and design were developed by LL, XW, FJ and LC. Material preparation and data collection were by FJ. Data extraction was by BB. Data analysis was performed by LL, BB and MG. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LL. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Wang, X., Gui, M. et al. Investigation of multimorbidity patterns and association rules in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using association rules mining algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 25741 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09926-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09926-8