Abstract

Cryopreservation of rooster sperm is a vital technique in avian reproductive management; however, it is often hindered by oxidative stress induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS) that negatively impact sperm quality during the freezing-thawing process. The present study aimed to investigate the impact of elamipretide, a mitochondria-targeted peptide, on sperm quality post-thaw. Sperm samples from 32-week-old broiler breeder roosters were cryopreserved using a Lake extender buffer with glycerol as the cryoprotectant. Four different concentrations of elamipretide (0, 6, 9, and 12 µmol/L) were tested in combination with the extender. Post-thaw sperm quality was evaluated by assessing motility, kinematic parameters, membrane integrity, mitochondrial activity, ROS levels as a direct marker of oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, cell viability, and antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, GPx and TAC). Sperm motility increased significantly at the 6 µmol/L (60.33 ± 1.54) and 9 µmol/L (64.96 ± 1.96) concentrations compared to the control, with the highest straight-line velocity observed at 9 µmol/L (21.21 ± 0.59). Membrane integrity also improved significantly at 9 µmol/L (61.78 ± 2.70) compared to lower doses (36.30 ± 1.64) and decreased at 12 µmol/L (49.57 ± 1.63). ROS production was significantly lower at 6 µmol/L (2.88 ± 0.07). Mitochondrial activity peaked at 9 µmol/L (60.21 ± 1.92), reflecting enhanced cell vitality and function. However, the effects were diminished at 12 µmol/L, indicating toxicity at higher concentrations. This study demonstrates the potential of elamipretide to improve rooster sperm cryopreservation outcomes by mitigating oxidative damage and preserving sperm quality post-thaw.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cryopreservation is an important technique in the preservation of sperm cells1. However, freezing and subsequent thawing of the samples almost always result in considerable damage, including reduced motility, viability, and fertility potential2,3. These detrimental effects are primarily attributed to oxidative stress resulting from the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which impair both the structural integrity and functional capacity of sperm cells4,5. In view of this challenge, studies have increasingly focused on antioxidants and mitochondrial protectors that enhance the resilience of sperm during cryopreservation6,7,8.

In the last years, particular interest has been focused on elamipretide, a mitochondria-targeted peptide, as a new promising additive to be used for improving sperm cryopreservation outcomes9,10. This compound exerts its beneficial effect on mitochondrial functionality and reduces lipid peroxidation by stabilizing mitochondrial membranes and mitigating oxidative stress, two of the most critical factors affecting the quality of spermatozoa after thawing7,11. Evidence from mammalian studies underlines its efficacy: in bull spermatozoa, 5 and 10 µM improved motility, mitochondrial potential, and acrosome integrity12. It improved motility, membrane stability, and mitochondrial function of human sperm at comparable concentrations. The most important benefits of elamipretide, however, involve a reduction in oxidative stress in frozen-thawed sperm, as evidenced by decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and lower levels of lipid peroxidation—both of which are key indicators of cellular oxidative damage. Indeed, experiments show that treatment with elamipretide significantly decreases ROS production and lipid peroxidation levels12. Such a reduction of oxidative stress is critical toward maintaining integrity and functionality in sperm via cryopreservation. By reducing the rate of oxidative damage, elamipretide is responsible for ensuring that the sperm cells can retain their functional capabilities after thawing9.

While these indeed are promising results, the possible benefits of elamipretide for avian sperm cryopreservation have not been fully realized to date. Rooster sperm is highly susceptible to ROS-induced lipid peroxidation due to its high polyunsaturated fatty acid content, which makes finding methods for mitigating oxidative stress highly relevant13. Adding mitochondrial protectors, such as elamipretide might offer a new strategy for maintaining post-thaw sperm quality through protection of the fragile mitochondrial architecture and by reducing oxidative injury14,15,16.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the antioxidant effects of elamipretide on the post-thaw quality of rooster sperm. By targeting mitochondrial function and reducing oxidative stress, this research provides new insights into how elamipretide can enhance sperm viability, motility, and overall quality after freezing and thawing, contributing to the improvement of cryopreservation outcomes in poultry species.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

The chemical reagents utilized in this study were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA).

Animal ethics

This study is in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. All animal care and procedures were approved by the University Ethical Committee of the University of Tehran. In addition, all methods used in the current study were carried out under the University Review Board and University Ethical Committee of the University of Tehran guidelines and regulations.

Using bird’s

The experimental work used ten Ross 308 broiler breeder roosters, 32 weeks old. These were separately caged in houses measuring 70 × 95 × 85 cm at 18 to 20 °C and maintained on a photoperiod of 15 L: 9 D. A dietary formula containing 12% of crude protein, 2750 kcal/kg metabolizable energy, 0.7% of calcium, 0.35% available phosphorus was provided with water at all times through the period of the experiment17.

Collection of semen

Abdominal massage was used to collect semen (twice a week). The ejaculates of ten roosters were consequently delivered to the laboratory within five minutes of its collection in an insulated container at 37 °C for evaluation of its quality. This temperature was chosen to minimize thermal shock during the short transit period prior to immediate evaluation and processing. On each collection day, ejaculates were immediately evaluated for quality, and those meeting the inclusion criteria (sperm concentration: 3.5 ± 0.3 × 10⁹ sperm cells/ml, sperm volume: 0.35 ± 0.05 ml, total motility: 85.2 ± 3.1%, and normal morphology: 88.6 ± 2.5%) were pooled in equal volumes to form one replicate. For the cryopreservation procedure, a total of seven pooled semen samples were used, each comprising equal aliquots from the ten roosters (1 ejaculate per male; 10 ejaculates per pool). Pooling was employed to minimize individual variability and ensure consistency across experimental treatments18.

Cryopreservation

Based on effective concentrations reported in mammalian sperm cryopreservation studies, four different concentrations of elamipretide (0, 6, 9, and 12 µmol/L) were tested in combination with the extender. The Lake extender buffer formed the basis of the basal freezing medium used in this study. Both pH and osmolality of the extender were lowered to 7.1 and 310 mOsm/kg, respectively. To this basic medium was added the major cryoprotectant glycerol at a concentration of 3.8% (v/v)19. Then the Lake extender containing glycerol was added with elamipretide to final treatment concentrations of 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 µmol/L elamipretide. The diluted semen was then loaded in to French straws (0.25 ml, IMV, L’Aigle, France) to get 100 × 106 sperm cells/straws. The straws, once sealed, were placed in a cryobox and equilibrated by holding them 6 cm above the surface of liquid nitrogen for 10 min. Following this equilibration period, the straws were immersed directly into a liquid nitrogen tank for storage. The results were evaluated after one week of storage by thawing the straws in a water bath at 37 °C for 30 s20.

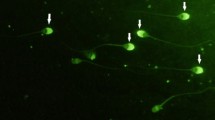

Computer-aided examination of sperm

Sperm motility parameters were measured by a computer-assisted sperm analyzer, CASA system (Hamilton Thorne CASA V 12.2, HTM-IVOS II software; Hamilton Thorne Biosciences, Beverly, MA, USA). Frozen semen samples were diluted 1:10 with Lake buffer for CASA analysis to achieve an optimal sperm concentration of 20 × 106 sperm/mL. Three µL of thawed sperm were loaded on to a preheated chamber (Leja, Nieuw-Vannep, Netherlands). Sperm motility was evaluated under a phase-contrast microscope at a total magnification of 100×. These settings of the CASA used in the experiment are as follows: frame rate, 60 Hz; number of frames acquired, 30; minimum contrast, 60; particle area = 5 < 190 mm2. The following parameters were evaluated: total motility (%), progressive motility (%), straightness (%), average path velocity (µm/s), straight line velocity (µm/s), curvilinear velocity (µm/s), amplitude of lateral head displacement (µm), beat cross-frequency (Hz), and linearity (%). For each evaluation, at least five fields (200 cells per evaluation) were randomly scanned21.

Abnormal morphology

To 10 µL of semen sample, 1 milliliter of Hancock’s solution was added, which was prepared by adding 65.5 mL formalin (37%) to 150 mL normal saline solution and 150 mL buffer solution and topped up to 500 µL with double-distilled water. A coverslip was placed to hold 5 µL of the mixture on a slide. Under a phase-contrast microscope at 1000×, 300 sperm were counted for percentage of sperm with abnormal acrosome, detached head, abnormal mid-pieces, and tail22.

The Hypo-Osmotic Swelling Test (HOST)

The hypo-osmotic swelling test (HOST) was performed as described by Santiago-Moreno, et al.23. The hypo-osmotic test was conducted by adding 100 µL of fructose and sodium citrate solution, each dissolved at a rate of 9 and 4.9 g per liter of distilled water, respectively, at the osmolality of 100 mOsm, respectively, to 10 µl of ejaculated semen sample, for incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Later on, 5 µL of this mixture was transfer to coverslip-covered and pre warmed slide. Using a phase-contrast microscope at 400× magnification, 200 sperm from at least 10 microscopic areas were counted to determine the proportion with inflated and coiled tails.

ROS assay

ROS was assayed by using the method Sangani, et al.24. Following 20 min of incubation in 250 µL of PBS at 37 °C, the semen samples were centrifuged at 300 g for 7 min and the supernatant extracted. The pellet was then added with 3 mL of PBS and centrifuged for 7 min at 300 g. After that, the sperm were diluted with PBS to get the concentration down to 20 × 106 mL. The tubes were then placed in an Orion II Microplate Luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany) for analysis after the addition of 400 µL of sample and 10 µL of luminol. The results were expressed as 103 sperm/106 cpm.

Evaluation of TAC, SOD, and GPx

The total antioxidant ability has been measured with total antioxidant status-RANDOX. This method works on the principle that antioxidants scavenge the ABTS cation radical. The samples were mixed with 1 ml of chromogen (ABTS reagent) in a volume of 20 µl, and the reaction was started by adding 200 µl of H2O2. This method produces a stable blue-green color that can be quantified by spectrophotometry with a maximum light absorption of 600 nm. The activity of GPX enzyme was assayed using RANSEL (SD125). The above-mentioned reaction mixture was created by adding 500 µl of GPx Reagent [glutathione, glutathione reducase and NADPH] and 10 µl of Buffer [EDTA and Phosphate Buffer] to 10 µl of sample, followed by the addition of 4 µl of cumene hydroperoxide. Absorption was read at the wavelength of 340 nm. Superoxide dismutase activity was determined by using RANSOD kit number SD 125. The assay principle is based on the interaction of superoxide radicals, produced by xanthine and xanthine oxidase with INT, resulting in a red formazan dye. This process is inhibited to different extents depending on SOD activity; this is then measured by calculation of SOD activity. In summary, 1.7 mL of the mixed substrate solution containing xanthine and INT was added to 50 µL of the sperm samples. Then, xanthine oxidase solution 500 µl was added to start the reaction. The absorption wavelength is at 505 nm25.

Flow cytometric analysis

A Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with a 488-nm argon laser was used to quantify phosphatidylserine externalization and mitochondrial activity. Green and red fluorescence emission were monitored by the system through the use of 530/30 nm [Annexin V-FITC and rhodamine 123] and 610/20 nm [PI] bandpass filters, respectively. Sperm were gated using forward/side scatter signals in all studies, and each sample analyzed contained 10.000 cells. Quantitative flow cytometry data were recorded using the program CellQuest 3.326.

Externalization of phosphatidylserine

Externalization of phosphatidyl serine as a sign of death in sperm was assessed by PI and annexin V-FITC kit [PI, Annexin VFITC, IQP, Groningen, and The Netherlands]. The samples, after washing in calcium buffer, were adjusted to contain 1 × 106 spermatozoa/ml. Then, 100 µL of the sperm suspension was mixed with 5 µL Annexin V FITC 0.01 mg/mL and incubated for 20 min at room temperature (22 °C). Sperm suspension was incubated at 22 °C for at least 10 min with 5 µL of PI. Then, the sperm suspension was stained by Annexin V-FITC and PI, and by flow cytometry, the sperm subpopulations were divided into four groups: (1) viable sperm that are both PI and Annexin V-FITC negative; (2) early apoptotic sperm that are both Annexin V-FITC positive and PI negative; (3) late apoptotic sperm that are both Annexin V-FITC positive and PI positive; and (4) necrotic sperm that are both Annexin V-FITC negative and PI positive. PI uptake was considered an indication that the sperm belonged to either the necrotic or late apoptotic subgroups and that they were dead27.

Mitochondrial activity

Diluted semen samples (100 mL; 50 × 106 sperm/mL) were mixed with 5 µL of Rhodamine 123 (R123; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) (0.01 mg/mL) and incubated at room temperature in the dark to measure the mitochondrial activity of sperm. Then, the sample, after adding 5 µL of PI solution 1 mg/mL, was analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the total amount of surviving sperm with active mitochondria both PI negative and R123 positive28.

Statistical analysis

Sperm evaluation was performed according to description earlier in this work; after that, pooled semen was cryopreserved in seven replicates. Data were examined using linear mixed-effects models using the R statistical platform (R Team, 2024). Results are represented as mean ± SEM. Where P < 0.05, significant differences in means were considered using Tukey’s multiple-comparison corrections method.

Results

Sperm motility and kinematics

Elamipretide exhibited a dose-dependent effect on sperm motility, with an optimal performance observed at intermediate concentrations (6 and 9 µmol/L), as shown in Table 1. Total motility (TM) increased significantly at 6 µmol/L (60.33 ± 1.54) and peaked at 9 µmol/L (64.96 ± 1.96). However, TM markedly declined at 12 µmol/L (51.97 ± 2.26), suggesting the onset of toxicity or adverse effects at higher doses. Progressive motility (PM) followed a similar trend. Kinematic parameters further highlighted the optimal effects of elamipretide. Average path velocity (VAP), curvilinear velocity (VCL), linearity (LIN), straightness (STR), and amplitude of lateral head displacement (ALH) showed no statistically significant differences between treatments (P ≥ 0.05) (see Table 1).

Membrane integrity and structural stability

The results depicted in Fig. 1 illustrate substantial improvements in membrane integrity with elamipretide treatment. Starting at 36.30 ± 1.64 in the control group (0 µmol/L), membrane integrity increased significantly with rising concentrations, peaking at 61.78 ± 2.70 at 9 µmol/L. A sharp reduction in membrane integrity was observed at 12 µmol/L (49.57 ± 1.63).

Mitochondrial activity (Fig. 1c) closely followed the trends observed for membrane integrity. A peak was observed at 9 µmol/L (60.21 ± 1.92), reflecting enhanced mitochondrial function and energy production. At 12 µmol/L, mitochondrial activity significantly decreased to 45.74 ± 1.25.

Viability and sperm apoptosis

Elamipretide significantly reduced sperm apoptosis (Fig. 2b) and enhanced cell viability (Fig. 2a). In the control group, apoptotic sperm percentages were relatively high, while treatment with elamipretide lowered these values, reaching the lowest levels at 9 µmol/L. Similarly, the percentage of dead sperm decreased markedly with treatment (Fig. 2c), reflecting improved cellular integrity and viability. However, at 12 µmol/L, apoptosis and cell death increased again, indicating potential adverse effects at this concentration.

Antioxidant enzyme activity

Specifically, Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (Fig. 3b) was significantly elevated at 6 µmol/L and peaked at 9 µmol/L compared to the control group. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity (Fig. 3d) also significantly increased at 6 µmol/L and reached its highest level at 9 µmol/L. Similarly, Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) (Fig. 3c) was significantly higher at 6 µmol/L and 9 µmol/L. The impact of elamipretide on oxidative stress was evident from ROS measurements in Fig. 3a. ROS levels decreased significantly (P < 0.05) at 6 µmol/L (2.88 ± 0.07) and were further reduced (P < 0.05) or maintained at a similarly low level at 9 µmol/L when compared to the control group (0 µmol/L). However, a significant increase (P < 0.05) in ROS levels was observed at the 12 µmol/L concentration, indicating that the protective effects were diminished and potentially reversed at this higher concentration.

Discussion

This study highlights the dual and dose-dependent functions of elamipretide both as a mitochondrial stabilizer and an antioxidant in improving sperm function and cryopreservation outcomes. Of particular note is the enhancement of sperm motility observed at intermediate concentrations, especially 6 µmol/L and 9 µmol/L, indicating its therapeutic potential. These effects align with existing evidence on the efficacy of mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants in reproductive technologies.

For instance, the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant Mitoquinone (MitoQ) improved post-thaw sperm motility by enhancing mitochondrial membrane potential and reducing oxidative stress during cryopreservation8. Astaxanthin from natural sources has also been shown to improve sperm motility and mitochondrial function in aging roosters29. In addition, this finding agrees with Kowalczyk and Czerniawska Piątkowska12where it was shown that the optimum improvement in motility is observed at concentrations of 5–10 µM for bull sperm cryopreservation. These improvements in motility are because of enhanced mitochondrial function and repressed oxidative stress during the cryopreservation process. In addition, Bai, et al.9present that optimum motility improvements were induced in human sperm cells exposed to 1–10 µM elamipretide since such intermediate concentrations averted mitochondrial dysfunction and maintained cell energy states.

Concentrations of 12 µM identified a drop in sperm motility to 51.97% ± 2.26, which paralleled observations from studies using human sperm. Such decline indicates a cytotoxic threshold beyond which the stabilizing effects of elamipretide are compromised, an effect probably related to oxidative overload30. The biphasic response of this study, regarding the dose-response relationship, underlines that careful optimizations of concentrations are necessary for therapeutic efficacy31.

Studies have shown that cryopreservation can lead to a failure in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in heightened ROS and decreased ATP32,33,34. Bai, et al.9stated that the action of elamipretide on mitochondria enhances mitochondrial membrane potential and decreases the generation of ROS. This is reflected in our observation that mitochondrial activity at 9 µmol/L was the highest, corresponding to heightened ATP production presumably used for motility. Elamipretide is known to achieve such effects by selectively interacting with cardiolipin, a key phospholipid of the inner mitochondrial membrane15. This binding helps to prevent cardiolipin’s peroxidation, thereby stabilizing the mitochondrial cristae architecture and supporting the efficient function of the electron transport chain components. The further decrease in the levels of ROS at lower concentrations of elamipretide also supports such antioxidant properties of this compound identified in previous studies. The further decrease in the levels of ROS at lower concentrations of elamipretide also supports such antioxidant properties of this compound identified in previous studies by Arjun, et al.8. Similarly, based on our results showing increased straight line velocity at 9 µmol/L, it would seem that elamipretide enhances mitochondrial function, crucial for sperm motility. Our result is in agreement with Obi, et al.10who in detail described how elamipretide stabilizes cardiolipin, an important molecule maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential. Both our study and that by Bai, et al.9 pointed toward a biphasic response to elamipretide, where lower concentrations increase sperm parameters while at higher concentrations 12 µmol/L in our case-motility and viability are significantly reduced. This is in agreement with the findings of Bravo, et al.35who reported that excessive oxidative stress could lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and impair sperm motility. The decrease in motility at higher concentrations in our study indicates that while elamipretide exerts a protective effect, it may also be toxic at high concentration, as is the case in other compounds studied in the context of oxidative stress8.

These actions act to explain the concurrent reduction in levels of ROS at 6 µM, in tandem with the established antioxidant capability of elamipretide. In this respect, Bai, et al.9have seen a similar dose-dependent effect where optimal ROS scavenging happened under lower doses of Elamipretide. Protection against oxidative stress-induced sperm apoptosis is thus afforded to the sperm by these antioxidant effects; this is one of the problems when cryopreservation is pursued.

The highest antioxidant enzyme activity was at 9 µM, expressed by TAC and GPX. These findings are in agreement with Kowalczyk and Czerniawska Piątkowska12who, in discussing bull sperm cryopreservation, recorded increased enzymatic activity at moderate concentrations of elamipretide. Besides optimizing enzymatic defenses against ROS levels, elamipretide preserves intracellular homeostasis essential for cell survival.

It significantly increased plasma membrane integrity at 9 µM with a recording of 61.78% ± 2.70, further pointing toward the role of elamipretide in structural stability. Stabilization of membranes can lower susceptibility to osmotic and mechanical damages during cryopreservation; the same was mentioned earlier in studies about bull and human sperm9,12.

Cell viability data further confirm these advantages. The rate of viability reached a maximum at 61.72% ± 0.81 at 9 µM, while the proportion of apoptotic and necrotic cells was the lowest. These trends are in line with the results obtained by Kowalczyk and Czerniawska Piątkowska12who reported that elamipretide treatments minimized membrane disruptions and apoptotic markers during stress. On the other hand, the decrease in viability at 12 µM, coupled with the rise in apoptotic activity, reflects the threshold beyond which elamipretide protective effects are overtaken by cytotoxic stress.

While the present in vitro study provides strong evidence for the benefits of elamipretide by demonstrating significant improvements in key sperm quality parameters such as motility, membrane integrity, mitochondrial function, and reduced oxidative stress, further research is warranted. Future studies should ideally progress to in vivo fertility trials to confirm these positive effects on reproductive outcomes in a practical setting. Additionally, investigating the efficacy of elamipretide in roosters of varying age groups, particularly older birds who may exhibit different baseline sperm quality or cryosensitivity, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of its potential applications in avian reproductive management. While our in vitro addition of elamipretide directly to the extender might suggest its fundamental mechanism of action on sperm mitochondria would be consistent, the overall benefit could be modulated by age-related factors inherent in the sperm cells.

Conclusion

Elamipretide shows great potential as a cryoprotective agent, significantly improving sperm motility, mitochondrial function, membrane integrity, and cellular viability at optimal concentrations of 6 and 9 µmol/L. Its antioxidant properties, including reduced ROS levels and enhanced enzymatic activity, support its role in mitigating oxidative stress during cryopreservation. By stabilizing mitochondrial membranes and maintaining intracellular energy production, elamipretide provides crucial advancements for reproductive technologies.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Mehaisen, G. M. K., Partyka, A., Ligocka, Z. & Nizanski, W. Cryoprotective effect of melatonin supplementation on post-thawed rooster sperm quality. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 212, 106238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2019.106238 (2020).

Partyka, A., Strojecki, M. & Nizanski, W. Cyclodextrins or cholesterol-loaded-cyclodextrins? A better choice for improved cryosurvival of chicken spermatozoa. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 193, 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2018.04.076 (2018).

Partyka, A., Nizanski, W., Bajzert, J., Lukaszewicz, E. & Ochota, M. The effect of cysteine and superoxide dismutase on the quality of post-thawed chicken sperm. Cryobiology 67, 132–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryobiol.2013.06.002 (2013).

Elomda, A. M. et al. The characteristics of frozen-thawed rooster sperm using various intracellular cryoprotectants. Poult. Sci. 103, 104190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.104190 (2024).

Partyka, A., Babapour, A., Mikita, M., Adeniran, S. & Nizanski, W. Lipid peroxidation in avian semen. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 26, 497–509. https://doi.org/10.24425/pjvs.2023.145050 (2023).

Wu, J. Y. et al. Effect of natural Astaxanthin on sperm quality and mitochondrial function of breeder rooster semen cryopreservation. Cryobiology 117, 104979 (2024).

Tiwari, S., Dewry, R., Srivastava, R., Nath, S. & Mohanty, T. Targeted antioxidant delivery modulates mitochondrial functions, ameliorates oxidative stress and preserve sperm quality during cryopreservation. Theriogenology 179, 22–31 (2022).

Arjun, V. et al. Effect of mitochondria-targeted antioxidant on the regulation of the mitochondrial function of sperm during cryopreservation. Andrologia 54, e14431 (2022).

Bai, H. et al. Elamipretide as a potential candidate for relieving Cryodamage to human spermatozoa during cryopreservation. Cryobiology 95, 138–142 (2020).

Obi, C., Smith, A. T., Hughes, G. J. & Adeboye, A. A. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction with Elamipretide. Heart Fail. Rev. 27, 1925–1932 (2022).

Masoudi, R., Asadzadeh, N. & Sharafi, M. Effects of freezing extender supplementation with mitochondria-targeted antioxidant Mito-TEMPO on frozen-thawed rooster semen quality and reproductive performance. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 225, 106671 (2021).

Kowalczyk, A. & Czerniawska Piątkowska, E. Antioxidant effect of Elamipretide on bull’s sperm cells during freezing/thawing process. Andrology 9, 1275–1281 (2021).

Oke, O. et al. Oxidative stress in poultry production. Poultry Science. 103, 104003 (2024).

Tung, C. et al. A review of its structure, mechanism of action, and therapeutic potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 944 (2025). Elamipretide.

Sabbah, H. N. et al. Contemporary insights into elamipretide’s mitochondrial mechanism of action and therapeutic effects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 187, 118056 (2025).

Mason, S. A., Wadley, G. D., Keske, M. A. & Parker, L. Effect of mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants on glycaemic control, cardiovascular health, and oxidative stress in humans: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes. Metabolism. 24, 1047–1060 (2022).

Lotfi, S., Mehri, M., Sharafi, M. & Masoudi, R. Hyaluronic acid improves frozen-thawed sperm quality and fertility potential in rooster. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 184, 204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2017.07.018 (2017).

Shahverdi, A. et al. Fertility and flow cytometric evaluations of frozen-thawed rooster semen in cryopreservation medium containing low-density lipoprotein. Theriogenology 83, 78–85 (2015).

Feyzi, S., Sharafi, M. & Rahimi, S. Stress preconditioning of rooster semen before cryopreservation improves fertility potential of thawed sperm. Poult. Sci. 97, 2582–2590. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pey067 (2018).

Mehdipour, M., Daghigh-Kia, H., Najafi, A., Mehdipour, Z. & Mohammadi, H. Protective effect of Rosiglitazone on microscopic and oxidative stress parameters of Ram sperm after freeze-thawing. Sci. Rep. 12, 13981. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18298-2 (2022).

Thananurak, P., Vongpralup, T., Sittikasamkit, C. & Sakwiwatkul, K. Optimization of Trehalose concentration in semen freezing extender in Thai native chicken semen. Thai J. Veterinary Med. 46, 287–294 (2016).

Schäfer, S. & Holzmann, A. The use of transmigration and spermac (tm) stain to evaluate epididymal Cat spermatozoa. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 59, 201–211 (2000).

Santiago-Moreno, J. et al. Use of the hypo-osmotic swelling test and aniline blue staining to improve the evaluation of seasonal sperm variation in native Spanish free-range poultry. Poult. Sci. 88, 2661–2669 (2009).

Sangani, A. K., Masoudi, A. & Torshizi, R. V. Association of mitochondrial function and sperm progressivity in slow-and fast-growing roosters. Poult. Sci. 96, 211–219 (2017).

Najafi, A. et al. Effect of tempol and straw size on rooster sperm quality and fertility after post-thawing. Sci. Rep. 12, 12192 (2022).

Najafi, A., Daghigh-Kia, H., Mehdipour, M., Mohammadi, H. & Hamishehkar, H. Comparing the effect of rooster semen extender supplemented with gamma-oryzanol and its nano form on post-thaw sperm quality and fertility. Poult. Sci. 101, 101637 (2022).

Askarianzadeh, Z., Sharafi, M. & Torshizi, M. A. K. Sperm quality characteristics and fertilization capacity after cryopreservation of rooster semen in extender exposed to a magnetic field. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 198, 37–46 (2018).

Sun, L. et al. Does antioxidant mitoquinone (MitoQ) ameliorate oxidative stress in frozen–thawed rooster sperm? Animals 12, 3181 (2022).

Gao, S. et al. Natural Astaxanthin improves testosterone synthesis and sperm mitochondrial function in aging roosters. Antioxidants 11, 1684 (2022).

Szeto, H. H. First-in‐class cardiolipin‐protective compound as a therapeutic agent to restore mitochondrial bioenergetics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2029–2050 (2014).

Celik, I. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of endostatin exhibits a biphasic dose-response curve. Cancer Res. 65, 11044–11050 (2005).

Gualtieri, R. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress caused by cryopreservation in reproductive cells. Antioxidants 10, 337 (2021).

Zhu, Q. et al. Melatonin protects mitochondrial function and inhibits oxidative damage against the decline of human oocytes development caused by prolonged cryopreservation. Cells 11, 4018 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Damage to mitochondria during the cryopreservation, causing ROS leakage, leading to oxidative stress and decreased quality of Ram sperm. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 59, e14737 (2024).

Bravo, A., Sánchez, R., Zambrano, F. & Uribe, P. Exogenous oxidative stress in human spermatozoa induces opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: effect on mitochondrial function, sperm motility and induction of cell death. Antioxidants 13, 739 (2024).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N and S D.Sh: Collecting the data, Writing – original draft and Writing – review & editing, Supervision. R.F and Sh H.B: Carrying out the experiments and collecting the data, Writing–original draft, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. All animal care and procedures were approved by the University Ethical Committee of the University of Tehran. In addition, all methods used in the current study were carried out under the University Review Board and University Ethical Committee of the University of Tehran guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Najafi, A., Sharifi, S.D., Farhadi, R. et al. Elamipretide enhances post-thaw rooster sperm quality by mitigating oxidative stress and optimizing mitochondrial function during cryopreservation. Sci Rep 15, 23564 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09943-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09943-7