Abstract

With the vigorous construction of water conservancy projects in the cold regions of western China, the frost heaving cracking problem of rock mass fissures in cold regions under the water-ice phase change seriously threatens the safety of projects. This study aims to explore the fracture laws of rock masses containing random fissures under frost heaving, providing a basis for frost-resistant design and disaster prevention in cold region projects. The study uses the Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) method. A failure coefficient, a discrete format of the heat conduction equation, and an equivalent thermal expansion coefficient method are introduced to build the model. The Monte Carlo method is used to generate random fissures, and numerical simulations are carried out by setting different fissure lengths, numbers, and dip angles. The results show that different fissure lengths, numbers, and dip angles have different effects on the frost heaving failure patterns of rocks. An increase in length makes secondary cracks more likely to overlap, the cracks become coarser, more complex, and their expansion accelerates. An increase in the number of fissures makes the crack distribution denser, the overlapping and merging of cracks accelerate, and they are distributed in blocks. Changes in the dip angle affect the crack direction, finally, through-going cracks can be formed. By comparing with previous experiments, the rationality of the simulation method is verified. Although the SPH method has certain advantages, there are differences between the simplifications of random fissures and the actual situation. In the follow-up, a three-dimensional SPH method should be developed and combined with non-destructive testing techniques to more accurately simulate the frost heaving mechanical behavior of rocks and support the construction of rock engineering in cold regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

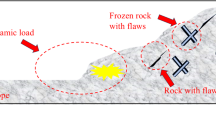

In China, the area of permanent and seasonal cold regions accounts for approximately 75% of the total national territory, mainly distributed in the western and northern regions. With the implementation of the Western Development Strategy and the Belt and Road Initiative, the construction of water conservancy projects in the western cold regions is advancing rapidly. Currently, the Jinsha River Hydropower Base, known as the “top of China’s 13 major hydropower bases,” is also under rapid construction. The Jinsha River Hydropower Base stretches over 2,300 km, with its climate gradually transitioning from the plateau climate in Yushu, Qinghai in the upper reaches to the subtropical monsoon climate in Yibin, Sichuan in the lower reaches. The hydropower stations in the upper reaches of the Jinsha River are characterized by strong seasonality, large diurnal temperature differences, and intense freeze - thaw weathering effects. Moreover, most of these hydropower stations are built in alpine valleys, where the rock masses are rich in numerous fractures1,2. Since part of the rock slopes along the reservoir banks is submerged below the reservoir water level, the water inside the rock mass fissures (especially in the case of saturated fissure water) undergoes a water - ice phase change under the low - temperature environment in cold regions, generating frost heaving forces on the fissure surfaces. As a result, the fissures expand, leading to frequent slope collapse disasters (Fig. 1). For example, a landslide occurred in Zhenxiong County, Yunnan Province, along the Jinsha River due to frost heaving, resulting in 44 deaths. This seriously threatens the safety of the lives and property of residents along the river and the operation safety of reservoir dams within the basin.

Due to the fact that the frost heaving fracture process of fissured rock masses involves complex multi - field and multi - phase coupling as well as discontinuous problems, numerical simulation is required. Currently, numerical simulation research on the frost heaving fracture process of rock masses has attracted the attention of scholars. Initially, the finite element method/finite difference method was used to simulate the frost heaving fracture of rock masses under multi - field coupling. For example, Tan et al.3 established a multi - field coupling model of rock masses under low - temperature freeze - thaw based on the finite element method and simulated the frost heaving process of pipeline projects in cold regions. Liu et al.4 used FLAC3D to establish a thermo - mechanical coupling model for single - fissure frost heaving and obtained the stress field distribution near the fissures under frost heaving. Li et al.5 simulated the freeze - thaw cycle process of indoor rock samples based on the FLAC3D software. The finite element method/finite difference method generally reflects the failure of rock masses by using plastic penetration zones or damage variables. Therefore, it is difficult to truly simulate the entire process of crack initiation, propagation, and failure in rock masses. With the development of numerical simulation technology, the discrete element method, due to its good ability to simulate large - deformations and discontinuous problems, has been widely applied to the analysis of the fracture process of rock masses. For example, Song et al.6 proposed a water - ice particle phase - change coupling expansion method based on the discrete element method and achieved the simulation of the freeze - thaw fracture process of rock masses. Jia et al.7 considered the freeze - thaw damage process of saturated rock samples and simulated and analyzed the crack propagation process of rock samples under freeze - thaw - stress coupling conditions based on the discrete element method. However, the discrete element method generally requires the calibration of micro - contact parameters, which has certain empiricism8. Later, scholars improved the finite element method and the discrete element method to better simulate the freeze - thaw deterioration process of rocks. For example, Tan et al.9 used the extended finite element method to study the interaction between multiple cracks in frozen rocks. Tang et al.10simulated and studied the influence of the angles of double - coplanar fissures and ice - fissure rock bridges on their tensile behavior based on the RFPA2D thermal - force analysis module independently developed by the team. Sun et al11. simulated the frost - crack propagation process of single - fissure specimens by using a low - temperature thermal - force coupling model combined with the finite - discrete element method (FDEM). Tang et al.12 reproduced the freeze - thaw expansion and penetration process of multiple fissures by using the AiFrac - TOUGH joint simulation technology. However, these methods are still essentially based on the frameworks of the finite element method and the discrete element method and still have certain problems.

In fact, the frost heaving fracture process of fissured rock masses includes the entire process from the generation of frost heaving forces to the large - deformation failure of the rock mass structure caused by crack expansion. Currently, for the simulation of large - deformations of rock masses, methods such as the discontinuous deformation analysis method, the discrete element method, and the meshless method are mainly used. Representative programs include DDA (Shi et al.13, Yang et al.14, Zhuang et al.15), DEM (Liu et al.16), and SPH (Zhou et al.17, Li et al.18), etc. The DDA and DEM methods are mainly used to simulate the large - deformations of fractured rock masses and the block collapse process. The frost heaving failure of fractured rock masses involves low - temperature multi - field and multi - phase coupling as well as discontinuous fracture behavior. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the research of the simulation method for the evolution process of frost heaving forces inside the fissures of rock masses under the multi - phase coupling of water - ice - rock and the entire process of rock mass cracking and failure induced by it. SPH (Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics), as a pure Lagrangian meshless method, not only has the advantages of the traditional finite element method in dealing with multi - field coupling problems but also can better simulate large - deformations and discontinuous problems19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Moreover, the governing equations of SPH use actual physical parameters and do not require complex meso - parameter calibration. In addition, SPH can conveniently handle the complex multi - phase interaction process of water - ice - rock during the frost heaving process of fractured rock masses. Therefore, it is very suitable for simulating the multi - field and multi - phase coupling and discontinuous frost heaving failure process of the fractured rock masses. However, there are a large number of randomly distributed fissures inside rocks, and there are few studies on the expansion and overlapping laws of fissures considering random distribution under the water - ice phase change.

In view of the shortcomings of previous studies, in this paper, a failure coefficient ε is introduced into the traditional SPH framework, which can realize the simulation of the progressive failure process of rocks. The SPH discrete format of the heat conduction equation and the equivalent thermal expansion coefficient method are introduced to realize the simulation of the frost heaving failure of rocks within the SPH framework. A method for generating random fissures of rocks within the SPH framework is proposed, and numerical simulations of the frost heaving expansion of random fissures with different fissure lengths, numbers, and inclinations are carried out. The research results can provide a reference for the application of SPH in fracture mechanics of rocks in cold regions.

Basic principles of SPH

Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH), as a meshless Lagrangian method, demonstrates unique advantages when dealing with complex fluid dynamics problems such as large - deformation multiphase flows. Its core idea is that the continuous fluid medium is discretized into a series of particles with properties like mass, velocity, and pressure, and the motion of the fluid is simulated through the interactions among these particles. The kernel approximation method and the particle approximation method are the key techniques of the SPH method, and they determine the approximation accuracy of the SPH algorithm for continuous fields and the computational efficiency.

Kernel function approximation and particle approximation method

The kernel function W(x, h) is the core of the kernel approximation method, which describes the weight of the interactions between particles. Consider a continuous function f(x) defined on the spatial domain Ω, and it can be approximately integrated through the kernel function W(x, h), that is:

Where 〈 〉is the approximation symbol;〈f(x)〉is the approximate form of the function.

f(x) at x;Ω is the size of the interaction domain of a specific particle x.

Another approximate expression of the kernel function for the first - order derivative of an SPH function is:

In SPH, the continuous fluid medium is discretized into N particles with mass mi. For the continuous function f(xi), its kernel approximation at particle i can be approximated by summing up the contributions of all particles:

According to Eq. (2), referring to the particle approximation method, it can be further rewritten, and its expression can be written as:

Governing equations

In the SPH method, the continuity equation and the momentum equation are crucial for describing the mechanical behavior of solids. The continuity equation essentially reflects the law of conservation of mass, and the momentum equation is used to describe the change law of momentum during the motion of solids. Their expressions can be written as17:

Where α、β are Einstein notations.

Implementation method for the Frost heaving fracture process in SPH

Introduction of the heat conduction equations

The heat conduction equation describes the law of change in temperature within a substance with respect to time and space, revealing the intrinsic mechanism of heat transfer within an object. Its expression can be written as:

In Eq. (7), ρ is the density; c is the specific heat capacity; k is the thermal conductivity; t is time; and Tem is temperature. The heat conduction equation is a second-order partial differential equation. Referring to previous treatments, the second-order partial differential equation can be decomposed into two first-order partial differential equations by introducing the heat flux vector q, which is expressed as:

Discretizing Eqs. (8) and (9) by SPH according to Eq. (4), their expressions can be written as:

Temperature stress equation

In SPH, Hooke’s law is used to represent the stress-strain relationship of solids. Stress mainly consists of hydrostatic pressure p, shear stress τ, and temperature stress, and its expression can be written as:

Where B is the shear modulus and λ is the coefficient of thermal expansion.

Particle failure treatment methods in the SPH framework

In the field of rock mechanics, rocks are subjected to complex and diverse stress conditions. Accurately determining when rocks will fail is of utmost importance. As a significant strength theory, the maximum principal stress criterion finds extensive application in rock research. Since rocks are mostly brittle materials, their failure mode under load is primarily brittle fracture. Through the observation and analysis of numerous rock failure phenomena, it has been found that the maximum principal stress plays a decisive role in the process of rock brittle fracture. This criterion posits that regardless of the complex stress state a rock is in, once the maximum principal stress reaches the rock’s tensile strength, brittle failure will occur. Based on this characteristic, in rock engineering projects such as tunnel excavation and mining, engineers utilize the maximum principal stress criterion to evaluate the stability of rocks, determine the safety of rock structures, and subsequently make rational engineering design and construction decisions. This section introduces the most commonly used maximum tensile stress criterion, that is, when the maximum principal stress σ1 exceeds the tensile strength σt of an SPH particle, the particle fails. Therefore, its expression can be written as:

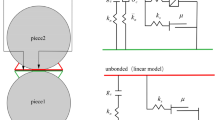

To characterize the fracture failure process of particles, a failure coefficient ε is introduced. When a particle fails, it is denoted as ε = 0, conversely, it is denoted as ε = 1, The particle failure process within the SPH framework is illustrated in Fig. 2. Therefore, based on the traditional SPH governing Eqs. (5) and (6), the SPH governing equations considering particle failure can be expressed as:

Random fissure generation method in the SPH framework

In the complex geological environment of cold regions, rocks are continuously subjected to freeze - thaw cycles over a long period. Frost heaving failure has become a key issue threatening the stability of infrastructure. Random fissures are widely distributed inside rocks, and their lengths, widths, attitudes, and spatial distributions are highly uncertain. These fissures, like “weak zones”, greatly alter the physical and mechanical properties of rocks. When the temperature drops rapidly, the water in the fissures freezes and expands, generating stress concentration at the fissure tips, which accelerates the expansion and connection of fissures. As the number of freeze - thaw cycles increases, the fracture network continues to develop, leading to a reduction in rock strength and an increase in permeability. This, in turn, triggers a series of engineering disasters such as slope instability, tunnel lining cracking, and foundation frost heave uplift. Therefore, it is particularly necessary to fully consider the distribution of random fissures inside rocks in numerical simulations. By accurately simulating the initiation, expansion, and evolution processes of fissures under the action of frost heaving forces, it is possible to deeply reveal the mechanism of frost heaving failure, provide a scientific basis for the anti - freezing design of projects in cold regions and disaster prevention, and effectively improve the safety and durability of engineering structures in frost heaving environments.

There are numerous fissures inside rocks, and it is generally difficult to accurately determine their internal geometric structures. However, their spatial distributions follow statistical laws. That is, the lengths, dip angles, etc. of the fissures can be described by probability - statistical density functions. This section introduces the commonly used Monte Carlo method, and the linear congruential method is used to generate uniformly distributed random numbers. Its recurrence formula is expressed as follows:

Where M is the modulus, mod M represents taking the remainder with respect to the modulus; a is the multiplier; c is the increment; x0 is the initial value; rn is the random number generated between (0 ~ 1), Therefore, the formula for random numbers that follow a normal distribution can be expressed as:

Where µx is the mean value and σx is the standard deviation.

For two - dimensional fissures inside rocks, their characteristics can be represented by the coordinates of the fissure center point (fx0,fy0), the length of the fissure l, and the direction angle of the fissure α. Therefore, the coordinates of the fissure endpoints can be written as:

Where fx is the abscissa of the fissure endpoint and fy is the ordinate of the fissure endpoint.

Analysis of numerical simulation results

Numerical model and calculation scheme

In order to explore the influence of the geometric characteristics and distribution of the internal fissures of the rock mass on the frost heaving and cracking morphology of the rock under the water-ice phase change, the following calculation schemes are set: Scheme A: Different fissure lengths l. Scheme B: Different numbers of fissures n. Scheme C: Different fissure dip angles α. The details of the specific calculation schemes are shown in Table 1. The rock mass model is a cuboid model with the size of 60 mm×120 mm, and the whole model is divided into 150 × 300 = 45,000 particles in total. The random fissures are generated according to Sect. 4 in this article. The model is subjected to the freeze-thaw cycle load ranging from − 20℃~20℃. The size of the model and the meshing of the particles are shown in Fig. 3. The parameters of the model are as follows: The elastic modulus E = 17GPa, the Poisson’s ratio µ = 0.2, and the tensile strength σt = 2Mpa.

Influence of different fissure lengths l on the Frost heave failure of rock

Figure 4 presents the frost heave cracking processes of rocks with different fissure lengths l. As the ambient temperature drops, the water inside the fissures gradually changes from a liquid state to a liquid-solid mixed state and then to a solid state. With a further decrease in temperature, due to the water-ice phase change inside the rock fissures, a frost heave force is generated, which exerts an extrusion effect on the fissure surfaces. Frost heave cracks initiate and propagate from the surfaces of the long fissures. Cracks that propagate along the direction of the prefabricated long fissures are called “main cracks”, while those that form on the prefabricated fissure surfaces and are nearly perpendicular to the prefabricated fissures are called “secondary cracks”. It can be seen from the figure that for a fissure length l = 5mm, the “main crack” propagates along the direction of the prefabricated fissure (i.e., at a 45°angle to the horizontal direction), and the “secondary cracks” extend from the two ends of the “main crack” in a direction perpendicular to the prefabricated long fissure. During the propagation of the “secondary cracks”, when they extend to the area of an adjacent fissure and overlap with it, the cracks will continue to extend towards the model boundary. As the cracks continue to propagate, the originally independent cracks will merge, resulting in a reduction in the number of cracks. The cracks become coarser and more complex, and finally, several open frost heave crack propagation patterns are formed. For a fissure length l = 10mm, the “main crack” propagates along the direction of the prefabricated fissure (i.e., at a 45° angle to the horizontal direction). Under the premise that the number of fissures and the fissure inclination remain constant, due to the relatively large fissure length, the secondary cracks are more likely to extend to the area of an adjacent fissure and overlap during their propagation. As the cracks continue to propagate, the originally independent cracks will merge more quickly, leading to a more significant reduction in the number of cracks. The crack structure becomes coarser and more complex, and finally, a frost heave crack that almost penetrates the entire rectangular model is formed. For a fissure length l = 15mm, under the premise that the number of fissures and the fissure inclination remain constant, due to the further increase in fissure length, when the “main crack” extends along the direction of the prefabricated fissure (i.e., at a 45°angle to the horizontal direction), it may merge with an adjacent “main crack” to form a single fissure. The development of the “secondary cracks” is similar to the previous analysis. The dominant “secondary cracks” and the “main crack” continue to propagate and overlap with each other, and they merge into a thick and complex crack in the model, which extends towards the model boundary. Finally, a frost heave crack that penetrates the entire rectangular model is formed.

For a fissure length l = 20 mm, the continuous increase in fissure length does not lead to significant changes. The frost heave propagation pattern of the crack is similar to that of the specimen with l = 15 mm, but the difference is that the cracks are coarser and more complex, and the crack propagation speed is also slightly accelerated.

Influence of different numbers of fissures n on the Frost heave failure of rock

Figure 5 presents the frost heave cracking processes of rocks with different numbers of fissures n. As the ambient temperature decreases, the water within the fissures undergoes a phase transition from a liquid state to a liquid-solid mixture and finally to a solid state. With a further drop in temperature, the water-ice phase change within the rock fissures generates a frost heave force, which exerts pressure on the fissure surfaces. Frost heave cracks initiate and propagate from the tips of the pre-existing fissures. The cracks propagating along the direction of the prefabricated fissures are termed “main cracks,” while those forming on the prefabricated fissure surfaces and nearly perpendicular to the prefabricated fissures are referred to as “secondary cracks.” It can be observed from the figure that when the number of fissures n = 12, the “main cracks” propagate along the direction of the prefabricated fissures (i.e., at a 45°angle to the horizontal direction), and the “secondary cracks” extend from both ends of the “main fissures” in a direction perpendicular to the prefabricated fissures. During the propagation of the “secondary cracks,” when they extend to the vicinity of adjacent cracks and intersect with them, the cracks continue to propagate toward the model boundary. As the cracks propagate, the originally isolated cracks coalesce, leading to a reduction in the number of cracks. The crack structure becomes coarser and more complex, ultimately forming several open frost heave crack propagation patterns. When the number of cracks n = 18, the “main cracks” propagate along the direction of the prefabricated fissures. With an increased number of fissures while keeping the fissure length and inclination constant, the probability of interaction between adjacent fissures rises. Consequently, the “secondary cracks” are more likely to extend to and intersect with adjacent fissures during propagation. As the cracks continue to propagate, the originally isolated fissures coalesce more rapidly, resulting in a more significant reduction in the number of cracks. The crack structure becomes coarser and more intricate, eventually forming a frost heave crack that nearly penetrates the entire rectangular model.

When the number of fissures n = 24, with a further increase in the number of fissures while maintaining constant fissure length and inclination, the interaction between fissures becomes more pronounced. The “main cracks” and “secondary cracks” propagate and intersect more frequently, leading to the rapid coalescence of fissures. As a result, the number of cracks decreases significantly, and the crack structure evolves into a complex network. Finally, a frost heave crack that penetrates the entire model is formed. When the number of fissures n = 30, the high density of fissures promotes extensive interaction and coalescence. The propagation and coalescence of cracks occur more rapidly, resulting in a coarser and more complex crack structures. The crack propagation speed increases slightly compared to the case with n = 24, and a frost heave crack that fully penetrates the model is formed.

Influence of different fissure inclinations α on the Frost heave failure of rock

The influence of different fissure inclinations α on the frost heave failure of rock masses is shown in Fig. 6. As can be seen from the figure, when the fissure inclination α is 30°, the “primary crack” propagates along the direction of the prefabricated fissure (i.e., 30° from the horizontal direction), while the “secondary cracks” extend perpendicularly from both ends of the prefabricated long fissure. During the propagation of secondary cracks, when they extend to the area of adjacent fissures and lap with them, the cracks continue to extend toward the boundary of the model. With the continuous propagation of cracks, the originally independent cracks merge, leading to a reduction in the number of cracks and a coarser and more complex crack structure, eventually forming frost heave cracks that almost penetrate the entire rectangular model.

For fissure inclinations α of 45°, 60°, and 75°, under the condition that the fissure length and number remain constant, only the propagation directions of the “primary cracks” along the prefabricated fissuree direction and the “secondary cracks” perpendicular to the prefabricated fissure direction change. Compared with the fissure inclination of 30°, no significant differences are observed in the propagation degree and rate of the prefabricated fissures. With the further propagation of cracks, the differences caused by fissure inclinations gradually decrease, and finally, frost heave cracks that almost penetrate the entire rectangular model are formed in all cases.

Discussion

Comparison between numerical simulation results and previous experimental results

Figure 7 presents a comparison between the numerical simulation results of this study and previous experimental results26. As shown in the figure, under the action of frost heave forces, the inner frost heave cracks of the prefabricated double fissures connect to the ends of adjacent prefabricated fissures. Meanwhile, the outer tips of the two prefabricated fissures generate frost heave cracks that propagate approximately along the direction of the original prefabricated fissures and extend to the ends of the model, leading to model failure. The consistency between the numerical simulation results and the experimental results verifies the rationality of the numerical simulation method in this study.

Comparison between the numerical simulation results of this study and previous experimental results. (a) Numerical simulation results of this study; (b) Previous experimental results26.

Application prospects of the SPH method in simulating Frost heave propagation of random fissures in rocks

In the field of rock mechanics, simulating the propagation of rock fractures under frost heave is of great significance for understanding geological disasters in cold regions and the stability of underground engineering. Traditional finite element method (FEM) and discrete element method (DEM) have certain limitations in addressing rock frost heave failure problems, while the smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) method demonstrates unique advantages and broad application prospects in simulating frost heave propagation of random fissures in rocks.

The finite element method, based on mesh division, is prone to distortion or even failure of the mesh when dealing with large deformation and dynamic crack extension problems, making it difficult to accurately capture the complex evolution of cracks during rock frost heave. Although the discrete element method can effectively simulate the interaction between particles and the motion of particle systems, its computational efficiency is low, resulting in excessive simulation costs for large-scale, continuous medium rock models. In contrast, the SPH method, as a Lagrangian meshless method, does not require mesh division of the computational domain. By discretizing the continuous medium into interacting particles, it can naturally handle large deformation, fracture, and other discontinuous problems. During the simulation of rock frost heave and cracking, it can more accurately describe the initiation, expansion, and penetration of cracks, and has relatively high computational efficiency, especially suitable for simulating complex boundary conditions and dynamic processes.

However, in the simulation study of frost heave propagation of random fissures in rocks conducted in this paper, the treatment of random fissures is mostly based on the assumption that they follow a certain probability distribution. Although this assumption simplifies the research to a certain extent, it has significant differences from the complex morphology of fissures in actual rocks, limiting the accuracy and reliability of the simulation results. Therefore, future research should focus on developing a three-dimensional SPH method and combining it with advanced non-destructive testing technologies, such as X-ray computed tomography (CT) and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to obtain the geometric information of actual rock fissures and reconstruct high-precision three-dimensional rock fracture models. Through simulating and predicting frost heave failure using these three-dimensional models, the mechanical behavior of rocks under frost heave can be more realistically reflected, providing a more scientific theoretical basis for the design of rock engineering and disaster prevention in cold regions.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Based on the smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) method, this study introduced a failure coefficient, a discrete format for the heat conduction equation, and an equivalent thermal expansion coefficient method to simulate the frost heave failure of rocks. Comparison with previous experimental results showed consistent propagation of frost heave cracks in prefabricated double fractures under frost heave forces, verifying the rationality of this numerical simulation method and providing a reliable approach for studying rock frost heave failure.

-

(2)

The length of fissures has a significant impact on the frost heave failure patterns of rocks. As the fissure length increases, the propagation direction of primary cracks remains unchanged, but secondary cracks are more prone to lapping, and the speed of crack coalescence accelerates. For example, crack propagation in the 5-mm fissure specimen is relatively slow, while cracks in the 20-mm fissure specimen are coarser, more complex, and propagate faster. Ultimately, fissures of different lengths lead to coarsening of the crack structure and the formation of open or through-going frost heave cracks in the model.

-

(3)

The increase in the number of fissures changes the frost heave damage process of rocks. With fewer numbers of fissures, there are fewer secondary cracks and the main cracks merge through bridging; As the number increases, the cracks become more densely distributed, with a significant increase in secondary cracks forming a network structure and accelerating the speed of overlap and merging. Samples with 30 fissures are similar to those with 24, but they are more tightly connected and expand faster, eventually resulting in cracks that are block-like distributed, covering most areas of the model.

-

(4)

The fissure inclination has a certain influence on the frost heave failure of rocks. When the fissure inclination is 30°, the primary cracks propagate along the direction of the prefabricated fissures, while the secondary cracks extend vertically and lap with each other. At 45°, 60°, and 75°, the orientations of the primary and secondary cracks change, but compared with the 30° case, there are no obvious differences in the propagation degree and rate of the prefabricated cracks. Eventually, frost heave cracks that almost penetrate the model are formed in all cases.

-

(5)

The SPH method has unique advantages in simulating the frost heave propagation of random fissures in rocks, as it can naturally handle large deformations and fracture problems with high computational efficiency. However, the current treatment of random fissures is based on probability distribution assumptions, which differ significantly from reality. In future research, three-dimensional SPH methods should be developed, combined with non-destructive testing technologies to obtain geometric information of actual fissures, and high-precision models should be reconstructed to provide a more scientific theoretical basis for rock engineering in cold regions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tariq, W., Rehman, G., Gardezi, S. & Ikram, N. Impact of fractures and diagenesis on reservoir potential of inner ramp paleocene carbonates exposed in Western part of the lesser Himalayas of Pakistan. J. Earth Sci. 34 (2), 536–555 (2023).

Shu, B. et al. Analysis of the hydraulic and heat transfer evolution mechanism of a single rock fracture. J. Earth Sci. 34 (1), 205–213 (2023).

Tan, X., Chen, W., Wu, G. & Zheng, P. Study of thermo-hydro-mechanical-damage (thmd) coupled model in the condition of freeze-thaw cycles and its application to cold region tunnels. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 32 (2), 239–250 (2013).

Liu, Q., Kang, Y. & Liu, X. Analysis of stress field and coupled thermo-mechanical simulation of single-fracture freezed rock masses. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 30 (2), 217–223 (2011).

Li, G., Li, N., Liu, N. & Zhu, C. Practical algorithm of THM coupling process with ice-water phase change based on FLAC3D. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 36 (Supp. 2), 3841–3851 (2017).

Song, Y. et al. Meso-fracture evolution characteristics of freeze-thawed sandstone based on discrete element method simulation. Rock. Soil. Mech. 44 (12), 3602–3615 (2023).

Jia, C. et al. Investigation on freeze-thaw damage mechanism of porous rock with discrete element method. Rock and Soil Mechanics, 45 (2), 588–600.[8], Tension-shear extension criteria used in PFC2D to reveal a brittle failure of rock bridges in rock slopes with stepped joints[J]. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2024, 295: 109807. (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. A numerical method to consider the interaction between multiple fractures in frozen rocks based on XFEM[J]. Comput. Geotech. 169, 106240 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. Failure behaviour of frozen rock with double ice-filled flaws under Brazilian splitting tension[J]. Eng. Fract. Mech. 304, 110124 (2024).

Sun, L., Tao, S. & Liu, Q. Frost Crack Propagation and Interaction in Fissured Rocks Subjected To freeze-thaw Cycles: Experimental and Numerical studies[J]561077–1097 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2023).

Tang, X. et al. The Propagation and Interaction of Cracks Under freeze-thaw Cycling in rock-like material[J]154105112 (International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2022).

Pei, J. Numerical manifold method and discontinuous deformation analysis. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 16 (3), 279–292 (1997).

Xu, D. et al. A New Contact Potential Based three-dimensional Discontinuous Deformation Analysis method[J]127104206 (International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2020).

Zheng, F., Zhuang, X., Zheng, H., Jiao, Y. & Timom, R. Kinetic analysis of polyhedral block system using an improved potential-based penalty function approach for explicit discontinuous deformation analysis[J]. Appl. Math. Model. 82, 314–335 (2020).

Liu, C., Le, T., Shi, B. & Zhu, Y. Discussion on three major problems of engineering application of the particle discrete element method. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 39 (6), 1142–1151 (2020).

Bi, J. & Zhou, X. A Novel Numerical Algorithm for Simulation of Initiation, Propagation and Coalescence of Flaws Subject To Internal Fluid Pressure and Vertical Stress in the Framework of General Particle dynamics[J]501833–1849 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2017). 3.

Su, Z., Wang, S., Li, D., Sheng, J. & Wu, W. SPH–DEM modeling overtopping failure of earthfill dams[J]. Acta Geotech. 19 (2), 953–970 (2024).

Yu, S., Ren, X., Zhang, J. & Sun, Z. Numerical Simulation on the Excavation Damage of Jinping Deep Tunnels Based on the SPH method[J]91 (Geomechanics and Geophysics for Geo-Energy and Geo-Resources, 2023).

Yu, S., Sun, Z., Yu, J., Yang, J. & Zhu, C. An improved meshless method for modeling the mesoscale cracking processes of concrete containing random aggregates and initial defects[J]. Constr. Build. Mater. 363, 129770 (2023).

Yu, S., Ren, X. & Zhang, J. Simulating the chemical-mechanical-damage coupling problems of cement-based materials using an improved smoothed particle hydrodynamics method[J]. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e2018 (2023).

Yu, S., Ren, X. & Zhang, J. Using an improved SPH algorithm to simulate thermo-hydro-mechanical-damage coupling problems in rock masses[J]. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 47, 103085 (2023).

Yu, S., Sun, Z. & Qian, W. A meshless method for modeling the microscopic drying shrinkage cracking processes of concrete and its applications[J]. Eng. Fract. Mech. 277, 109014 (2023).

Xiang, Z., Yu, S. & Wang, X. Modeling the hydraulic fracturing processes in shale formations using a meshless method. Water 16 (13), 1855 (2024).

Hu, X., Yu, S. & Gao, Y. Experimental and meshless numerical simulation on the crack propagation processes of marble SCB specimens[J]. Eng. Fract. Mech. 308, 110354 (2024).

Hu, X., Yu, S. & Ying, P. Effects of Fissure Locations on the Crack Propagation Morphologies of 3D Printing Tunnel Models: Experiments and Numerical simulations[J]133104631 (Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 2024).

Li, P., Tang, X., Liu, Q. & Luo, P. Experimental study on fracture characteristics and strength loss of intermittent fractured quasi-sandstone under freezing and thawing. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 39 (1), 115–125 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenwei Zhu, Xingyi Yang, Bin Liu and Xuejiao Han wrote the main manuscript text and Shuyang Yu did the numerical simulation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, W., Yang, X., Liu, B. et al. Meshless numerical simulation on Frost cracking of rock masses containing random fissures under water-ice phase change. Sci Rep 15, 24464 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09993-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09993-x