Abstract

To examine the nonlinear effects of adolescent self-control on mental health and investigate the mediating role of school adaptation and the moderating role of physical activity, we conducted psychological measurements on 2077 high school students from eight different schools using a psychological scale. The results revealed a U-shaped relationship between adolescent self-control and their mental health and school adaptation, with school adaptation mediating this relationship. Furthermore, physical activity was identified as a regulator of the indirect effects of self-control on mental health through school adaptation. This suggests that adolescents sometimes need to balance their focus between internal self-control and external adaptation strategies to succeed in school. This balancing act can lead to an overuse of self-control resources, resulting in "excessive adaptation," which negatively impacts their mental health. However, physical activity can help mitigate these negative effects by moderating the relationship between school adaptation and mental health. The study underscores the importance of balancing self-control and school adaptation in adolescents. It recommends that educators incorporate physical activity into routines to help maintain adolescents’ mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence is a peak period for individual physical and mental health development and serves as a transitional phase from the family to the broader society, holding significant importance in human socialization processes. During this stage, adolescents experience increased needs in areas such as social identity and integration compared to childhood, leading to heightened interaction with peers, schools, and society, and a greater desire for social integration into new environments1,2. Traditionally, parents have endeavored to cultivate “good” and "well-behaved" children, with the common belief that children with good self-control exhibit high levels of school adaptation and better mental health. However, in recent years, scholars have expressed divergent views on the education of “good” and "well-behaved" children. Behind the façade of “good” and "well-behaved" lies a negotiation between self-needs and external adaptation3. Excessive maturity may lead children to accommodate others at the expense of neglecting themselves4. Education should instead focus on the subjective existence of children, fostering the development and perfection of their minds and wisdom5. The development of adolescent mental health should not only consider external environmental factors but also internal ones6. Thus, maintaining a dynamic balance between adolescent self-control and school adaptation is of paramount importance for their mental health development. Previous research has mainly focused on the linear impact of adolescent self-control on mental health, but whether adolescent self-control consistently exerts positive effects on mental health remains to be explored. Moderate physical activity, as one of the four cornerstones of health proposed by the World Health Organization, plays a crucial role in the development of adolescent mental health7. In recent years, experts from various disciplines such as developmental psychology and sports science have increasingly focused on the influence of physical activity on adolescent mental health8. Existing studies have shown that physical activity contributes to improving self-awareness, enhancing attentional states, maintaining positive moods, and facilitating interpersonal interactions. Research focusing on adolescents has also demonstrated the unique role of physical activity in improving adolescent physical and mental health and preventing symptoms such as anxiety and depression9,10. The roles of school adaptation and physical activity as crucial factors influencing adolescent mental health in the context of the impact of self-control on mental health require further investigation. Based on this, this study aims to explore the nonlinear relationship between adolescent self-control and mental health from the perspectives of self-control resource depletion, excessive adaptation, and embodied cognition theory. It also aims to examine the mediating and moderating roles of school adaptation and physical activity, respectively, in the aforementioned relationships, with the goal of enriching the empirical research findings on adolescent self-control and mental health and further exploring the roles of school adaptation and physical activity in adolescent mental health, thus providing new insights into the factors influencing adolescent mental health.

Self-control and adolescent mental health

Currently, researchers have not reached a unified interpretation of the concept of self-control. The concept proposed by Baumeister, which emphasizes the process of inhibiting dominant responses or behaviors and replacing them with less frequently occurring but desired responses, is widely cited11. Combined with the definition and development of self-control in Chinese scholars, self-control is defined in this study as an individual’s active process of regulating his or her own psychology and behavior. As research on self-control progresses, scholars have described self-control mechanisms from different perspectives. The Self-Control Resource Model is one of the common theories. This model suggests that self-control is a limited psychological resource that is temporarily depleted after exertion (also referred to as “ego depletion”), and individuals can restore it through rest or relaxation12,13. Self-control resources determine the success or failure of self-control. Some studies have shown that during the ages of 12–17, there is an increase in self-control problems, followed by a decline thereafter14.

Adolescence, a crucial period for the development of self-control in individuals, also plays a significant role in assessing adolescent mental health and overall health status. A substantial body of research indicates a positive relationship between self-control and adolescent mental health15,16. Higher levels of self-control are associated with fewer physical and mental health symptoms17. Self-control during adolescence also promotes physical and mental health in adulthood18,19. However, recent studies have pointed out that self-control is not always beneficial for mental health and may sometimes have adverse effects. For example, excessive depletion of self-control resources may lead individuals who typically exhibit good behavior to engage in misconduct20; high depletion of self-control resources may lower levels of individuals’ prosocial behavior21; and depletion of self-control resources diminishes individuals’ optimistic expectations for the future22. The literature review revealed that researchers have found two different perspectives in studying the linear relationship between the two. A portion of scholars have found that self-control is beneficial to mental health, while others have found that self-control can also have some negative effects on an individual’s mental health. Self-control may have a dual effect, as suggested by the theory of resource depletion in self-control. And it is this double-edged sword effect that has led to the emergence of different viewpoints in the study of the relationship between the two by previous researchers. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the relationship between self-control and adolescent mental health may not simply grow linearly, but rather show a nonlinear relationship.

The mediating role of school adaptation

Students spend the majority of their time at school, which serves as a crucial environment for their learning, social interaction, self-awareness, and overall development. Therefore, adolescent school adaptation has long been a focal point of attention. Currently, researchers have not yet reached a unified concept of school adaptation. Drawing from the definition proposed by Hou Jing, school adaptation is defined as the condition in which students actively participate in school activities, demonstrate success in learning, interpersonal interactions, engagement in school activities, and emotional adaptation within the school context23. Some studies have indicated that adolescent school adaptation is influenced by self-control24,25,26. Students with good self-control demonstrate higher psychological resilience, stronger sense of social responsibility, and are less prone to aggressive behavior, which facilitates their school adaptation27,28,29. Adolescent school adaptation is closely related to their mental health. Existing research suggests that positive teacher-student relationships, school identification, and collective adaptation are protective factors for adolescent mental health30,31,32. School adaptation is an important indicator for evaluating the mental health of student populations, and good school adaptation is one of the manifestations of student mental health33.

As mentioned that the potential nonlinear impact of self-control on adolescent mental health raises uncertainties about the directionality of the mediating role of school adaptation in the process. It remains to be clarified whether school adaptation is associated with the nonlinear effects of self-control on adolescent mental health. Japanese scholar Kitamura Haruo proposed that individual adaptation includes external adaptation (individuals’ adaptation to external environments) and internal adaptation (individuals’ sense of satisfaction and happiness)34. Ishizu et al. defined excessive adaptation as the phenomenon where individuals, even if they reluctantly suppress internal needs, strive to adapt to external expectations and demands35. Existing research indicates that physiologically, students with excessive adaptation exhibit increased parasympathetic nervous system activity during school periods36, and psychologically, they are more prone to emotional disorders37 and other mental health issues. To better adapt to school, adolescents may experience excessive depletion of self-control resources, leading to the occurrence of excessive adaptation and subsequently influencing their mental health.

The moderating role of physical activity

The concept of physical activity was initially proposed by Caspersen, defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle contractions resulting in energy expenditure, encompassing frequency, intensity, duration, and type as core elements, and defined from an energy metabolism perspective as any behavior during waking hours exceeding 1.5 METs38. Adolescent physical activity encompasses any activity involving skeletal muscle contractions, both within and outside of school, which leads to energy expenditure and health benefits.

Embodied cognition theory, as a core concept in embodied philosophy, provides theoretical support for modern school physical education39. This theory posits that cognitive content and processes are determined by the body, with cognition, body, and environment forming a dynamic unity. According to embodied cognition theory, the body plays a crucial role in individual cognitive processes, with the structure, mode of activity, sensation, and movement experience of the body determining how individuals perceive themselves and the world40. Considering the concept of excessive adaptation, when individuals suppress their intrinsic selves due to external environmental factors, excessive adaptation occurs, indicating that external environment and individual cognition are necessary conditions for the occurrence of excessive adaptation. Combined with the notion of embodied cognition, physical activity provides more opportunities for socialization and enables students to develop positive social relationships with their peers. Good social support has a positive effect on mental health. During physical activity, students can receive support and encouragement from their peers, which can alleviate feelings of isolation and stress associated with over-adjustment to school, thus promoting mental health. In other words, physical activity can regulate the impact of school adaptation on adolescent mental health.

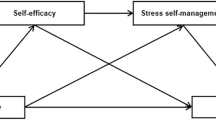

By combing and analyzing previous studies, we found a complex relationship between self-control, school adaptation, physical activity, and adolescent mental health, and proposed the following hypotheses for this study:

-

H1: There is a nonlinear relationship between self-control and adolescent mental health.

-

H2: There is a nonlinear relationship between self-control and adolescent school adaptation.

-

H3: School adaptation mediates the nonlinear relationship between adolescent self-control and mental health.

-

H4: Physical activity moderates the relationship between adolescent school adaptation and mental health.

-

H5: Physical activity moderates the indirect effect between adolescent self-control and mental health via school adaptation.

In summary, the theoretical model proposed in this study is depicted in Fig. 1.

Method

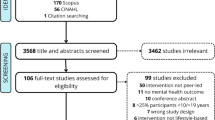

Participants

In order to ensure the representativeness of the selected samples, and to minimize the differences between regions. We selected one city from each of the four regions of Jiangsu Province (Central Jiangsu, Southern Jiangsu, Northern Jiangsu, and Nanjing) based on the economic and educational levels of the province, and one rural and one urban high school in each city, for a total of eight schools to distribute the questionnaires offline. The questionnaires were distributed with the approval of the ethical organizations in which they were administered and the consent of the participants or their guardians was obtained.

A total of 2345 questionnaires were collected in this study, and after cleaning invalid questionnaires, 2077 valid questionnaires were obtained, with a validity rate of 88.57%. There were nearly equal proportions of gender, different areas of domicile, and type of school.

Instruments

Self-control scale

Revised by Tan Shuhua41 et al., the five-point Likert scale with 19 items measures school adjustment in terms of Healthy Habits, Moderation in Entertainment, Resistance to Temptation, Focus on Work, and Impulse Control, with higher scores indicating better self-control. This scale is widely used in China to measure an individual’s degree of self-control.

Secondary school students’ mental health scale

Developed by Su Dan and Huang Xiting42, the five-point Likert scale with 25 items measures school adjustment in terms of Life Happiness, Enjoying Learning, Interpersonal Harmony, Calmness in Exams, and Emotional Stability, with higher scores indicating better mental health. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in measuring the mental health of Chinese secondary school students and has been widely used.

High school students’ school adaptation scale

Developed by Hou Jing43, the five-point Likert scale with 82 items measures school adjustment in terms of Learning Adaptationthis, Collective Adaptation, Peer Relationships, Emotional Adaptation, School Attitude, Teacher-Student Conflict, and Teacher-Student Intimacy, with higher scores indicating better school adaptation. The scale is also widely used in China and has high reliability and validity.

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

Administered using the short Chinese version developed by the International Physical Activity Working Group in 200144. This questionnaire assesses physical activity, walking, and sedentary behavior over the past 7 days and is suitable for individuals aged 15–69. It comprises seven items and utilizes Metabolic Equivalent of Energy (METs) values to assess physical activity levels (1 MET is equivalent to the energy expenditure or metabolic rate at rest, 1 MET = 3.5 ml of oxygen consumption per minute per kilogram of body weight). Higher MET values indicate higher levels of physical activity. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous studies .

The reliability and validity of the psychological scale used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

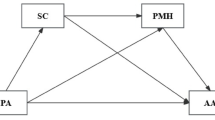

The study utilized SPSS 24.0, Medcurve, and Process for data analysis. The specific statistical analysis procedures are as follows: Conducting scale reliability and validity analysis, descriptive statistics, and correlation analysis using SPSS 24.0. Utilizing the Harman single-factor test to examine common method bias. Hypothesis testing using multiple linear regression. U-shaped hypothesis testing (Fig. 2): Using the non-linear expression Y = β0 + β1X + β2X2 + C where the regression coefficient β2 of the independent variable square is positive. Testing the hypothesis of mediation in non-linear relationships: Calculating the instantaneous mediation effect using Medcurve at levels where the independent variable is M − SD, M, and M + SD. If the 95% confidence intervals do not contain zero, it indicates a significant non-linear mediation effect of the mediator variable. Applying the Process plugin to test moderated mediation models.

Results

Common method bias test

Due to the subjective nature of the measurement items for the core variables of adolescent mental health, self-control, and school adaptation, there may be issues of common method bias45. Therefore, the Harman single-factor test was employed to test for common method bias. The results of the Harman single-factor test revealed that there were 18 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 22.927%, which did not exceed half of the total variance explained. Thus, this study does not exhibit serious common method bias issues.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Adolescents’ self-control score was (60.030 ± 12.558), mental health score was (87.518 ± 14.217), school adaptation score was (292.638 ± 45.737), and the value of physical activity meltdown was (1508.729 ± 1315.753).

Based on the characteristics of the variables, two-column correlation analysis was chosen for the correlation analysis between dichotomous variables and continuous variables, ANOVA was chosen for the correlation analysis between multicategorical variables and continuous variables, and Pearson’s correlation analysis or Spearman’s correlation analysis was chosen for the correlation analysis between continuous variables.

Correlation analysis of the control variables and adolescent mental health revealed that there were differences in adolescent mental health in different regions (F = 10.157, p < 0.001), there was a negative correlation between hukou location and adolescent mental health (r = − 0.045, p < 0.05), there was a positive correlation between gender and adolescent mental health (r = 0.121, p < 0.001), and there was a difference in the mental health level of adolescents from different family types (F = 6.813, p = 0.001). Correlation analysis of control variables and adolescent school adjustment revealed that there were differences in the level of adolescent school adaptation in different regions (F = 9.321, p < 0.001), and that there was a negative correlation between gender and the level of adolescent school adjustment (r = − 0.054, p = 0.013). In addition, there was a significant positive correlation between self-control and mental health (r = 0.595, p < 0.001), self-control and school adaptation (r = 0.545, p < 0.001), and school adaptation and mental health (r = 0.691, p < 0.001). The results of the correlation analysis were consistent with the research hypotheses and laid the foundation for subsequent hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis testing

The study employed multiple linear regression analysis for hypothesis testing. After standardizing the variables, all models’ VIF values were within the standard range during the regression analysis, indicating no significant multicollinearity among the variables, as shown in Table 2.

The first part focuses on the study of the effect of self-control on mental health and the mediating effect of school adaptation in their relationship. Mental health was taken as the dependent variable and controlled variables were included to obtain Model 1. Then, self-control was introduced as a linear and quadratic term to obtain Models 2 and 3. Firstly, the hypothesis of non-linear relationship was tested, revealing that the quadratic term of self-control had a significant positive effect on mental health (β = 0.057, p < 0.001). Thus, adolescent self-control exhibits a U-shaped effect on mental health, supporting hypothesis 1. Models 6 and 7 showed that the linear term of self-control was significantly positively correlated with school adaptation (β = 0.558, p < 0.001), and the quadratic term of self-control was also significantly positively correlated with school adaptation (β = 0.101, p < 0.001). Hence, adolescent self-control has a U-shaped effect on school adaptation. In Model 4, adolescent mental health was significantly positively influenced by school adaptation (β = 0.520, p < 0.001), and the regression coefficient of the quadratic term of self-control on adolescent mental health was not significant (β = 0.004, p = 0.668), indicating that school adaptation acts as a mediator. Thus, hypotheses 2 and 3 are both supported.

Further validation of the mediation effect of the non-linear relationship was conducted using the SPSS plugin Medcurve, with the results shown in Table 3. The results indicate that the instantaneous mediation effect is significant when self-control values are at M-SD, M, and M + SD levels. This suggests that school adaptation mediates the non-linear relationship between self-control and adolescent mental health, further confirming hypothesis 3.

To test hypothesis 4, after controlling for relevant variables, an interaction term "school adaptation × physical activity" was generated, and regression was performed with adolescent mental health as the dependent variable, as shown in Table 4. In Model 4, the interaction term "school adaptation × physical activity" reached significance (β = − 0.036, p < 0.05), supporting hypothesis 4. To further assess the moderation effect, the difference in the relationship between school adaptation and adolescent mental health at different levels of physical activity was examined, as depicted in Fig. 3. Simple slope analysis results indicated that when physical activity levels were high (M + 1SD), the impact of school adaptation on adolescent mental health was weaker (Effect = 0.635, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.563, 0.708]), whereas when physical activity levels were low (M − 1SD), the impact of school adaptation on adolescent mental health was stronger (Effect = 0.699, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.704, 0.657]).

The SPSS plug-in Process was used to test the mediation model for the second stage of being moderated, and the results are shown in Table 5.The results of the analyses showed that the indirect effect of self-control affecting adolescents’ mental health through school adaptation was significant when the level of physical activity was one standard deviation above the mean (Effect = 0.262, 95% CI [0.229, 0.293]), and the indirect effect of self-control affecting adolescents’ mental health through school adaptation was significant when the level of physical activity was one standard deviation below the mean, the indirect effect of self-control influencing adolescent mental health through school adaptation was significant (Effect = 0.295, 95% CI [0.261, 0.329]); the difference between the two was significant (ΔEffect = − 0.033, 95% CI [− 0.035, − 0.004]), indicating that this moderated mediation effect was significant and hypothesis 5 is supported.

Discussion

This study found a U-shaped relationship between adolescent self-control and mental health, which differs from the view in previous studies that the two have a linear relationship. Existing findings of the self-control resource depletion theory can partially explain the emergence of the U-shaped relationship between adolescent self-control and mental health. Based on the theory of depletion of self-control resources, scholars have already gained a basic consensus view through different types of research that (1) self-control resources are quite limited, but the depletion of resources is temporary46; and (2) the aftereffect of the depletion of self-control resources is longer, and it takes a longer period of time for the depletion of self-control resources to be recovered47; and (3) effective interventions can help alleviate self-control resource depletion. When individuals are in a state of depletion of self-control resources, they can promote the recovery of self-control resources by improving motivation48, replenishing energy49, and improving the capacity of self-control resources (e.g., following a regular routine, exercising physical strength, and monitoring the use of finances, etc.) through systematic training in everyday life capacity of self-control resources50,51,52, all of which help to mitigate the self-control resource depletion effect. To facilitate readers’ understanding, we assume the existing self-control resources of individual adolescents as water in a reservoir. Based on the above three ideas, we can clarify that the capacity of the reservoir (self-control resource pool) is limited, and when water is needed downstream (when the self-control resource depletion event occurs), the water in the reservoir (self-control resource) is temporarily used. In order to ensure that the water in the reservoir can be used sustainably, the reservoir manager (the individual himself), borrows a river (external self-control resource) upstream to inject water into the reservoir, which in turn is converged by a number of tributaries (different ways of restoring the self-control resource). It takes longer for the river to refill (self-control resource recovery) than for the reservoir to release (self-control resource depletion), so it takes longer for the self-control resource depletion to recover. In the following, we borrow the basic consensus of self-control resource depletion theory to explain in detail how the U-shaped relationship between adolescent self-control and mental health arises.

Firstly, in the decreasing segment of the U-shaped relationship, based on the theory of self-control resource depletion, the study suggests that in the early stages of self-control, continuous depletion of self-control resources can lead to self-control overload, resulting in self-depletion phenomenon and a decrease in adolescent mental health levels. That is, as adolescent self-control levels increase, mental health levels decrease. Faced with the continuous depletion of self-control resources, in order to cope with stressors and maintain mental health, individuals will engage in self-psychological adjustment primarily through defense and coping mechanisms53. Adolescents, in order to overcome the continuous depletion of self-control resources, will stimulate their own psychological defense mechanisms, slow down the depletion of self-control resources, and actively seek ways to restore self-control resources to cope with this depletion. However, at this point, the recovery of self-control resources is still lower than the total depletion, hence self-control and mental health remain in the declining segment of the U-shaped relationship. Brief depletion of self-control resources can be restored to normal levels through rest and other means54.

The example of a reservoir is illustrated in layman’s terms. In the descending section of the U-shaped relationship, the reservoir manager (the adolescent) realizes that water is needed downstream (a self-control resource depletion event occurs), and since the reservoir has sufficient water (self-control resource) at this point in time, the reservoir manager chooses to open the gates and release the water to solve the downstream water problem (the self-control resource begins to deplete). From the downstream viewpoint, the reservoir releases water well, and the downstream water shortage problem is alleviated (i.e., from the outside viewpoint, the level of self-control of the adolescents increases). However, in reality, as more and more water is released, the water in the reservoir has dropped to the warning line (self-control overload), and the entire reservoir system (adolescent mental health), which contains the reservoir (the pool of self-control resources) and the other facilities (the other psychological resources), begins to alarm. That is, the adolescent’s level of self-control increases, accompanied by the continued depletion of self-control resources, and the level of mental health decreases instead. Faced with the alarming status of the reservoir system, the administrator (adolescent) chose to reduce the water release to ensure only the minimum amount of water to address the downstream water problem (defense- and coping-based self-psychological conditioning) due to the cost of time (recovery of self-control resources is longer compared to the depletion of self-control resources). At the same time, the administrator opens the intake valve and borrows a river upstream to fill the reservoir with water (aggressively seeking ways to self-control resource recovery to cope with the depletion of that resource). However, due to the time lag between self-control resource recovery and depletion, the adolescents were able to escape from the continuous depletion of self-control resources by reducing the amount of self-control resource depletion and increasing the amount of self-control resource recovery. However, because of the previous excessive water shortage in the reservoir, at this point, the amount of self-control resource recovery is still lower than the total amount of depletion, and self-control and mental health are still in the declining segment of the U-shaped relationship.

When the depletion of self-control resources reaches a threshold (the lowest point of the U-shaped relationship), where the amount of depletion equals the amount of recovery, the impact of self-control on mental health reaches a turning point. If the recovery rate of self-control resources exceeds the depletion rate thereafter, adolescent mental health levels will improve, showing an upward trend in the U-shaped relationship. This upward trend is consistent with previous research conclusions, where an increase in adolescent self-control levels is associated with higher mental health levels17. Adolescent self-control and mental health exhibit a U-shaped relationship. If, after the turning point, the recovery rate of self-control resources is lower than the depletion rate, the long-term effects of self-depletion become prominent, leading to a qualitative change in adolescent mental health, and potentially the occurrence of psychological problems and even mental disorders55.

The reservoir example is still used for a generalized explanation. In the descending segment of the U-shaped relationship, despite the fact that water inflow > water outflow, the total amount of water inflow < previous depletion + current depletion due to the excessive amount of water shortage in the reservoir previously. Since the administrators (adolescents) have been actively expanding water intake (self-control resource recovery) and decreasing water outflow (self-control resource depletion), the reservoir water volume (self-control resource) always reaches an inflection point, i.e., total water intake = prior depletion + current depletion, at which point the total self-control resource depletion is equal to the amount of water recovered, and the total reservoir volume is no longer continually decreasing, and the health of the entire reservoir system (Mental health) ushered in the inflection point. However, at this time, the health (mental health) of the whole reservoir system still cannot reach the level before the water release (before self-control resource depletion), so the inflection point is the lowest point of the U-shaped relationship, rather than the highest point of the inverted U-shaped relationship. If the rate of water intake (the rate of self-control resource recovery) is faster than the rate of water discharge.

This study found that school adaptation plays a mediating role in the U-shaped relationship between self-control and adolescent mental health. Based on the theory of self-control resource depletion, the U-shaped relationship between adolescent self-control and mental health is related to the dynamic changes in self-control resource depletion and recovery. The theory of self-control resource depletion posits that the execution of all self-control behaviors depletes the energy in the self-control resource pool, and due to the limited total amount of resources, efforts in one area of self-control (such as impulse control, emotion regulation, interpersonal interactions, judgment and decision-making, etc.) will result in reduced energy available in other areas56. The theory of self-control resource depletion can also explain the mediating role of school adaptation. When the total reserve of self-control resources in adolescents is less than the demands of school adaptation, individuals will be in a state of surplus adaptation, where they reluctantly suppress internal needs and strive to adapt to the external environment. As the level of self-control increases, the state of surplus adaptation intensifies, leading to a decrease in adolescent mental health. Meanwhile, to cope with the continuous depletion of self-control resources caused by surplus adaptation, adolescents will alleviate the situation by reducing their level of school adaptation, i.e., under the state of surplus adaptation, the stronger the self-control of adolescents, the lower the level of school adaptation. When the total reserve of self-control resources equals the demands of school adaptation, the “rebound effect” is activated, leading to a significant accumulation of self-control resources in adolescents. With the reserve of self-control resources exceeding the demands of school adaptation, the increase in self-control level triggers an increase in the upper limit of school adaptation, resulting in a positive correlation between self-control and school adaptation in the U-shaped relationship. At this point, adolescent mental health levels increase as self-control levels increase. School adaptation is related to the dynamic changes in self-control resource depletion and recovery in adolescents, mediating the emergence of the U-shaped relationship between adolescent self-control and mental health.

This study found that the relationship between school adaptation and adolescent mental health varies depending on the level of physical activity: when physical activity levels are high, the impact of school adaptation on adolescent mental health is weaker; whereas when physical activity levels are low, the impact of school adaptation on adolescent mental health is stronger. In other words, physical activity can weaken the impact of school adaptation on adolescent mental health, making physical activity a moderating variable between school adaptation and adolescent mental health. Additionally, this study also indicates that while physical activity cannot directly regulate the U-shaped effect between self-control and adolescent mental health, it can regulate the indirect effects between adolescent self-control and mental health through school adaptation. Embodied cognition theory suggests that the concepts and categories through which individuals understand the world around them are determined by their bodies, with abstract concepts such as human progress and decline stemming from the unique physical structure of humans57. Adolescent physical activity can regulate their cognitive perceptions of internal resources and external environments, including their perceptions of self-control and school adaptation. Regular participation in physical activities can enhance self-control resources and school adaptation58,59. Studies have shown that high levels of leisure-time physical activity and moderate levels of work-time physical activity constitute the optimal combination of physical activities to reduce mental health problems60. Physical activity helps individuals break free from the fatigue of daily life, providing time for psychological resource recovery61, and also helps individuals reduce sensitivity to negative external feedback and alleviate mental fatigue62 Extracurricular physical exercise promotes school adaptation and mental health in adolescents63. Compared to adolescents with low physical activity levels, those with high physical activity levels achieve better school adaptation with fewer self-control resources mobilized and are less concerned about mental health issues caused by surplus adaptation.

In general, the results of this study provide the following insights for adolescent educators to maintain the mental health of adolescents: Firstly, dynamically assess the levels of self-control and school adaptation in adolescents. Given the U-shaped effect of self-control on school adaptation and mental health, teachers should pay attention to the compatibility of adolescents’ self-control levels and school adaptation levels. High school adaptation does not necessarily equate to mental health, and surplus adaptation also falls into the category of poor school adaptation. Moreover, “good children” and “obedient children” may exhibit hidden mental health issues. Secondly, the research focus on adolescent physical activity and mental health should be more diverse. While attention is given to the impact of physical activity on the mental health of adolescents with lower levels of self-control and poorer school adaptation, greater emphasis should also be placed on the unique role of physical activity in promoting the mental health of “good children” and “obedient children”. Considering that physical activity can weaken the indirect effects between adolescent self-control and mental health through school adaptation, educators can alleviate the psychological stress of adolescents who fall into a state of “surplus adaptation” due to excessive depletion of self-control resources by guiding them to engage in scientifically effective and diverse physical activities both inside and outside the campus.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations that provide implications for future research. Firstly, the use of self-reported measures for all variables in this study may impact the objectivity of the data. Future experimental studies could be conducted to further validate the underlying causal relationships. Secondly, while this study confirmed the non-linear impact of self-control on adolescent mental health, it did not identify the key factors directly influencing the opening and apex of the U-shaped curve. Lastly, further research is needed to explore targeted physical activities for adolescents experiencing surplus adaptation, in order to mitigate or resolve their mental health issues.

Conclusion

The findings of this study reveal a U-shaped relationship between self-control and adolescent mental health, indicating that both very low and very high levels of self-control can be detrimental. Furthermore, school adaptation is shown to mediate this relationship, and physical activity serves as a moderator for the indirect effects through school adaptation. These insights offer significant practical implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Programs aimed at fostering balanced self-control in adolescents should be emphasized, avoiding extremes that can lead to negative mental health outcomes. Enhancing school adaptation strategies and promoting regular physical activity can be effective interventions to support adolescent mental health.

Future research should explore the underlying mechanisms of these relationships in more detail and examine the longitudinal impacts of balanced self-control development. Additionally, studies could investigate the role of different types of physical activities and their specific effects on school adaptation and mental health. By addressing these areas, we can develop more targeted and effective strategies for improving adolescent well-being.

Data availability

Data availability The datasets generated during or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, W. W. et al. Developmental characteristics and influencing factors of children and adolescents’ social adaptation and promotion. J. Preschool Educ. Res. 12, 36–47 (2021).

Yao, Y. & Cheng, C. Peer networks and adolescent mental health. J. Youth Stud. 5, 24–34 (2021).

Cheng, L. Behind the well-behaved child. J. People’s Educ. 5, 6–8 (2015).

Zhang, T. T. & Zheng, H. “Being responsible”-educational implications in the expectation of growing up. J. Educ. Sci. Res. 5, 78–83 (2020).

Yuan, Z. J. “Good children”: A moral orientation that needs reflection. J. Preschool Educ. Res. 1, 18–22 (2012).

Meng, Z. W. Assessing contemporary adolescent mental health. J. People’s Forum. 1, 91–93 (2021).

Zhang, Y. T. et al. Chinese children and adolescents physical activity guidelines. J. Chin. J. Evidence-Based Pediatr. 12, 401–409 (2017).

Liu, Y. H. & Guo, Y. L. Research progress on adolescent psychological health from the perspective of exercise psychology. J. Hunan Normal Univ. (Educ. Sci. Edn.) 21, 115–122 (2022).

Sun, X. B. et al. Correlation analysis of high school students’ physical activity and symptoms of anxiety based on component-based time-substituted model. J. Modern Prevent. Med. 48, 3277–3280 (2021).

Yang, T. N. & Xiao, H. Physical activity and health effects in disabled children and adolescents: A systematic review of systematic reviews. J. Chin. J. Rehabil. Theory Practice. 28, 1299–1308 (2022).

Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F. & Tice, D. M. Losing control: How and why people fail at self-regulation. J. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 15, 367–368 (1995).

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D. & Tice, D. M. The strength model of self-control. J. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 16, 351–355 (2007).

Dou, K. et al. Self-depletion promotes impulsive decision making: evidence from behavioral and ERPs studies. J. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 46, 1564–1579 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Age and gender differences in self-control and its intergenerational transmission. J. Child Care Health Develop. 43, 274–280 (2017).

Ge, X. Y. & Hou, Y. B. A gentleman is not worried or afraid: The chain-mediated effect of gentlemanly personality on mental health—Self-control and authenticity. J. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 53, 374–386 (2021).

Hu, Q. et al. A systematic review of adolescent self-control research. J. Chin. J. Mental Health. 36, 129–134 (2022).

Boals, A., Vandellen, M. R. & Banks, J. B. The relationship between self-control and health: The mediating effect of avoidant coping. J. Psychol. Health. 26, 1049–1062 (2011).

Nishida, A. et al. Adolescent self-control predicts midlife hallucinatory experiences: 40-year follow-up of a national birth cohort. J. Schizophrenia Bull. 40, 1543–1551 (2014).

Yang, F. & Jiang, Y. Adolescent self-control and individual physical and mental health in adulthood: A Chinese study. J. Front. Psychol. 13, 850192 (2022).

Ren, J. et al. Psychological explanation of good people doing bad things: evidence from research on self-control resource depletion. J. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 46, 841–851 (2014).

Ma, L. Y. & Mo, W. The influence of positive emotions on prosocial behavior under self-depletion. J. Psychol. Behav. Res. 20, 684–691 (2022).

Li, M. P. & Lu, J. M. Feeling tired of love? Evidence from research on reducing optimistic expectations based on self-depletion. J. Psychol. Res. 15, 126–131 (2022).

Hou, J. Development and validation of a school adaptation scale for Junior High School Students. J. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 24, 413–420 (2016).

Ng-Knight, T. et al. A longitudinal study of self-control at the transition to secondary school: Considering the role of pubertal status and parenting. J. Adolesc. 50, 44–55 (2016).

Bai, Y. et al. The level of self-control of Chinese rural primary and secondary school students and its relationship with educational output. J. World Agric. 493, 12–19 (2020).

Zhang, Y. Y. et al. Father’s involvement in parenting and school adaptation of rural boarding junior high school students: The mediating role of self-control and the moderating role of relative deprivation. J. Psychol. Sci. 44, 1354–1360 (2021).

Song, M. H. et al. The influence of parenting styles on junior high school students’ aggressive behavior: The role of deviant peer association and self-control. J. Psychol. Develop. Educ. 33, 675–682 (2017).

Luo, L. et al. The relationship between parenting styles and college students’ sense of social responsibility: The mediating role of self-control and gender differences. J. Psychol. Develop. Educ. 34, 164–170 (2018).

Wang, J. Z. et al. The relationship between migrant children’s self-control and social adaptation: The mediating role of psychological resilience. J. Chin. Special Educ. 10, 70–75 (2019).

Patel, V. et al. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. J. Lancet. 369, 1302–1313 (2007).

Van der Horst, M. & Coffé, H. How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being. J. Social Indicators Res. 107, 509–529 (2012).

Liu, Y. et al. Perceived positive teacher-student relationship as a protective factor for Chinese left-behind children’s emotional and behavioural adjustment. J. Int. J. Psychol. 50, 354–362 (2015).

Savickas, M. L. & Porfeli, E. J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocational Behav. 80, 661–673 (2012).

Wang, X. A comparative study of excessive adaptation in middle school students in China and Japan. J. Ningbo Univ. (Educ. Sci. Edn.) 43, 51–58 (2021).

Ishizu, K. & Ambo, H. Tendency toward over-adaptation: School adjustment and stress responses. Japan. J. Educ. Psychol. 56, 23–31 (2008).

Sugawara, Y., Hiramoto, I. & Kodama, H. Over-adaptation and heart rate variability in Japanese high school girls. J. Autonomic Neurosci. 176, 78–84 (2013).

Abe, N., Abe, K. & Nakashima, K. The role of perceived stress and fear of negative evaluation in the process from alexithymia to over-adaptation. J. Psychol. 62, 217–232 (2020).

Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E. & Christenson, G. M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. J. Public Health Rep. 100, 126–131 (1985).

Zhou, S. W. & Cheng, C. G. Embodied physical education teaching: A practical perspective for implementing physical education curriculum standards. J. Tianjin Inst. Phys. Educ. 37, 504–510 (2022).

Ye, H. S. Embodied cognition: A new orientation in cognitive psychology. J. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 18, 705–710 (2010).

Tan, S. H. & Guo, Y. Y. Revision of the college student self-control scale. J. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 16, 468–470 (2008).

Su, D. & Huang, X. T. A preliminary study on the psychological health structure of middle school students’ adaptation orientation. J. Psychol. Sci. 30, 1290–1294 (2007).

Hou, J. Development of a school adaptation scale for high school students. J. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 21, 385–388 (2013).

Qu, N. N. & Li, K. X. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. J. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 25, 87–90 (2004).

Zhou, H. & Long, L. R. Statistical testing and control methods for common method bias. J. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 22, 942–950 (2004).

Muraven, M. & Baumeister, R. F. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle?. J. Psychol. Bull. 126, 247–259 (2000).

Vohs, K. D. et al. Making choices impairs subsequent self-control: A limited-resource account of decision making, self-regulation, and active initiative. J. Personality Social Psychol 94, 883–898 (2008).

Muraven, M. & Slessareva, E. Mechanisms of self-control failure: Motivation and limited resources. J. Personality Social Psychol. Bull. 29, 894–906 (2003).

Gailiot, M. T. et al. Self-control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor. J. Personality Social Psychol. 92, 325–336 (2007).

Oaten, M. & Cheng, K. lmproved self-control: The benefits of a regular program of academic study. J. Basic Appl. Social Psychol. 28, 1–16 (2006).

Oaten, M., Cheng, & K.,. Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. Br. J. Health Psychol. 11, 717–733 (2006).

Oaten, M. & Cheng, K. Improvements in self-control from financial monitoring. J. Econ. Psychol. 28, 487–501 (2007).

Liang, B. Y. & Cui, G. C. Psychological defense mechanisms and clinical practice. J. Chin. J. Mental Health. 7, 488–490 (2002).

Tan, S. H. et al. Self-depletion: Theory, influencing factors, and research directions. J. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 20, 715–725 (2012).

Chen, Y. Y. et al. A review of the aftereffects of self-depletion. J. Beijing Normal Univ. (Social Sci. Edn.) 228, 14–20 (2011).

Yu, B., Le, G. A. & Liu, H. J. The power model of self-control. J. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1272–1282 (2013).

Ye, H. S. Body and learning: Embodied cognition and its challenge to traditional educational views. J. Educ. Res. 36, 104–114 (2015).

Cao, M. et al. The mediating effect of self-concept on the relationship between physical activities and school adaptation among primary school students. J. Chin. J. School Health 39, 122–123 (2018).

Bollimbala, A., James, P. S. & Ganguli, S. Grooving, moving, and stretching out of the box! The role of recovery experiences in the relation between physical activity and creativity. J. Personality Individual Differences. 196, 11757 (2022).

Rodríguez-Romo, G. et al. Physical activity and mental health in undergraduate students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 195 (2022).

Jiang, N. P. et al. Roaming: accelerating the practice of deceleration among social youth groups. J. Chin. Youth Res. 324, 69–75 (2023).

Jacquet, T. et al. Physical activity and music to counteract mental fatigue. J. Neurosci. 478, 75–88 (2021).

Yan, J. et al. The relationship between extracurricular physical exercise and school adaptation in adolescents: A chain-mediation model and gender differences. J. China Sport Sci. 56, 11–18 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the teachers and principals who helped us in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (22ATY007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yueyan Jiang designed and wrote the main manuscript text. Chong Liu wrote and edited the manuscript. Yueyan Jiang and Chong Liu contributed equally to this study. Jun Yan reviewed and administrated the study. Lingzhi Wang assisted in data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical College of Yangzhou University (No. YXYLL-2022-109).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Liu, C., Yan, J. et al. The joint role of school adaptation and physical activity in the nonlinear effect of adolescent self-control and mental health. Sci Rep 15, 25277 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10011-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10011-3