Abstract

In-situ combustion (ISC) offers a compelling solution for enhancing oil recovery, particularly for heavy crude oils. This process involves the oxidation and pyrolysis of hydrocarbons, generating heat and depositing fuel in the combustion front. In this work, the thermo-oxidative profiles and residue formation of crude oils during thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) were modeled using 3075 experimental data points from 18 crude oils with API gravities ranging from 5 to 42. Four advanced tree-based machine learning algorithms comprising gradient boosting with categorical features support (CatBoost), light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), random forest (RF), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) were utilized to develop accurate predictive models. The results indicated that CatBoost outperformed the other models, achieving mean absolute relative error (MARE) values of 4.95% for the entire dataset, 5.92% for the testing subset, and 4.71% for the training subset. Moreover, it recorded a determination coefficient (R2) value of 0.9993, highlighting its exceptional predictive capability. Furthermore, temperature was identified as the most influential factor affecting residual crude oil content, exhibiting a significant negative correlation, while API gravity also showed a negative impact. Conversely, asphaltene, resin, and heating rate positively correlated with residual content. Finally, the leverage method demonstrated that only 2.14% of the data were identified as suspected, with no out-of-leverage points detected, underscoring the reliability of the CatBoost model and the gathered experimental data. Effective management of fuel consumption and residue formation is crucial for maintaining the ISC process, and the CatBoost model has demonstrated strong predictive capabilities that support this objective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the fact that the use of nonrenewable energy might be declining, this sector holds significant potential. Thus, promoting and expanding oil recovery methods is a pivotal step toward a more sustainable future in this inevitable industry. As a matter of fact, utilizing experiments and authentic outcomes of studies conducted with miraculous technological advances, some crucial behaviors of hydrocarbons will be predictable. Hence, the advancement of methodologies for oil recovery, especially through in-situ combustion (ISC), presents a promising thermal recovery technique. This process involves injecting air into a reservoir, which generates energy through oxidation reactions with crude oil. ISC is considered an effective approach for extracting heavy oil due to its strong displacement capabilities and associated cost efficiencies1,2,3. ICS process has proven effective as a follow-up to steam injection. This process involves injecting hot air to oxidize hydrocarbons or coke in oil reservoirs, creating a combustion front that generates substantial heat, leading to increased oil temperature and enhances mobility, maximizing recovery efficiency and making ISC an appealing option for oil extraction4,5. Before designing an ISC process, it is inevitable to understand the oxidation behavior of heavy oil with oxygen. In other words, improved ISC development requires modeling the fundamental reaction dynamic6,7. Although ISC has potential benefits, its industrial applications have faced criticism due to unclear oxidation mechanisms and combustion processes, leading to project failures8,9. This scenario holds the key to understanding the dynamic nature of coke deposition and combustion. To put it simply, examining the structural changes and combustion behavior of coke during the low-temperature oxidation (LTO) process provides insights that can improve ISC process for addressing inferior heavy oil reservoirs. Therefore, the characteristics and quantity of coke produced are crucial for ensuring the sustainability of the ISC process10,11,12. From this viewpoint, it is indispensable to comprehend how LTO affects the coking mechanism and the formation of coke, as this dramatically impacts the combustion process13. Another reaction region that might be happening in ISC is the negative temperature gradient region, which is considered a transitional zone between LTO and high-temperature oxidation (HTO) where the oxygen absorption rate reduces with rising temperature14,15. More importantly, heavy components are converted into lighter components to produce fuel for combustion16,17. HTO reactions are the most critical aspect of the ISC process because they release a considerable amount of heat. Typically, coke produced from LTO or thermal cracking is thought to serve as the primary fuel source for HTO reactions18,19.

Numerous studies have been conducted from both laboratory and system modeling perspectives to achieve a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of residue formation from crude oil during ISC. Belgrave et al.20 built a reaction model including thermal cracking reactions, LTO, and HTO, in which the bitumen was divided into two components, asphaltene and maltene. Yamamoto et al.21,22 built the Lattice Boltzmann model for propane combustion and subsequently simulated combustion, although they did not consider the effects of thermal expansion. Xu et al.23 studied coke deposition at varying oxidation temperatures for conventional heavy oil from Xinjiang. They found that the highest coke deposition occurred under LTO conditions and during coke combustion at HTO conditions, specifically within the LTO temperature range. Zhao et al.24,25 used practical outcomes and theoretical results to summarize LTO reaction pathways, significantly enhancing the understanding of LTO reactions. Askarova et al.26 conducted medium-pressure coking tests on crushed and consolidated core samples to examine ISC feasibility in a heavy-oil carbonate reservoir. Experiments analyzed phase behavior under high pressures and temperatures, highlighting that consolidated cores require increased air flux due to lower porosity.

In recent years, significant advancements have been made in the modeling and simulation of underground reservoirs, covering a wide range of topics, including enhanced oil recovery (EOR) processes, complex pore-scale fluid-rock interactions, thermal behavior of insulating oils, shales and coals, as well as ignition and combustion sciences27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Surprisingly, the advent of artificial intelligence has greatly changed various aspects of thermal EOR. Rasouli et al.36 applied thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to investigate the pyrolysis of six crude oils in a nitrogen atmosphere. A simple neural network model was developed to predict the residual crude oil based on temperature during pyrolysis, achieving an acceptable average relative error of about 3.5%. Then, Norouzpour et al.37 created radial basis function network models to anticipate the remaining mass of crudes during pyrolysis, using input parameters such as API density, viscosity, resin and asphaltene content, temperature, and heating rate. Their results indicated that the developed model can precisely anticipate remaining weight of crude oil during pyrolysis. In investigating this issue, Mohammadi et al.38 created general models for anticipating residual mass during the pyrolysis of crude oil. They utilized various neural network architectures. Their sensitivity analysis revealed that temperature and asphaltene content substantially influence mass loss. Furthermore, Mohammadi et al.39 modeled oxidation reactions during the ISC with advanced machine-learning techniques and 2289 experimental TGA data. Hadavimoghaddam et al.40 conducted a study to model crude oil pyrolysis during TGA using various machine learning techniques. Their results showed that higher temperatures and lower oil gravity decreased fuel deposition. Fuel formation from crude oil pyrolysis and oxidation is essential in ISC, as it generates the coke needed to sustain the combustion front. Proper fuel generation ensures continuous heat release, supporting effective oil recovery. The literature review reveals limited studies attempting to model these processes, with a focus primarily on pyrolysis over oxidation and a reliance on minimal crude oil TGA data. Hence, incorporating diverse crude oil data, emphasizing oxidation profiles, and utilizing advanced machine learning algorithms could aid in developing a robust model to predict residue formation during ISC.

In this study, the thermo-oxidative profiles and residue formation of crude oils during TGA are modeled using 3075 experimental data points from 18 crude oils with API gravities between 5 and 42. To develop accurate predictive models, four advanced tree-based machine learning algorithms were utilized: gradient boosting with categorical features support (CatBoost); light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM); random forest (RF); and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). To assess model performance, statistical metrics and graphical error analysis are utilized. Moreover, sensitivity analysis is conducted to investigate the relationships between input variables and the predictions of the top-performing model. Eventually, the leverage method is applied to assess the model’s validity and its applicable scope.

Data gathering and preprocessing

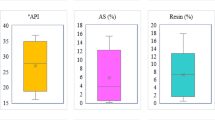

In the current work, a collection of 3075 TGA experimental data points, sourced from credible literature41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53, were gathered for the purpose of modeling crude oil oxidation. The models take into account ˚API gravity of the oil, asphaltenes (wt%), resins (wt%), the heating rate, and temperature as input variables. Meanwhile, the output of the models is residual crude oil (wt%) measured at varying temperatures. The selection of model input parameters is crucial for accurately capturing the key factors influencing the thermal decomposition of crude oil in TGA. The °API gravity, asphaltenes, and resins are essential for characterizing the crude oil, as these properties significantly impact its oxidation behavior. The inclusion of the heating rate and temperature as input variables reflects the operational conditions of TGA, providing a realistic representation of the thermal environment. This combination of parameters ensures a comprehensive model that effectively captures both the intrinsic characteristics of the crude oil and the external thermal conditions, aligning with the approaches demonstrated in prior studies39,52,54. Table 1 represents a summary of the properties of crude oils analyzed through TGA along with heating rates and temperature ranges of experiments. Moreover, Table 2 presents the statistical analysis of both the target and input variables for the gathered database in this work. The ranges of the input variables shown in Table 2 are as follows: °API gravity (5–42.03), asphaltene content (0.53–49.12 wt%), resin content (1.09–51.30 wt%), heating rate (2–30 °C/min), and temperature (25.25–821.62 °C). The target variable, crude oil residue, ranges from 0.03 to 100.00 wt.%. The data utilized for developing the machine learning models are included in the Supplementary Information accompanying this manuscript. Also, Fig. 1 depicts box plots for all variables in the dataset, showcasing key statistical indicators such as the quartiles, mean, median, minimum and maximum. A box plot, or whisker plot, is a graphical representation applied in data preprocessing to reveal the distribution of numerical data through their quartiles. This type of plot demonstrates a graphical summary of the minimum, first quartile (Q1), third quartile (Q3), median, and maximum values, making it easy to identify outliers and understand the data’s spread. The “box” indicates the interquartile range (IQR), containing 50% of the data between Q1 and Q3. Also, whiskers are limits extending from the box to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the IQR from Q1 and Q3, respectively. These plots offer a clear visual summary, making them an effective tool for analyzing the dataset’s statistical properties. As it is evident, the broad ranges for both input and target parameters are sufficient for developing a reliable model to anticipate crude oil oxidation behavior in TGA experiments.

Model development

CatBoost

CatBoost is a gradient boosting decision tree technique that is particularly adept at managing categorical features, which can have a substantial impact on predictive accuracy55. Introduced by Prokhorenkova et al.56, the CatBoost algorithm effectively transforms categorical variables into numerical representations utilizing greedy target-based statistics (Greedy TBS), necessitating limited hyperparameter adjustments57,58. Within its gradient-boosting architecture, it employs both non-symmetric and symmetric tree construction methods, initiating the process with a root node that encompasses all data. This method enhances the feature space by generating combinations of categorical features based on their interrelationships, employing greedy target-based statistics59. Additionally, CatBoost incorporates “ordered boosting” to mitigate the target leakage issue commonly associated with gradient boosting (GB) methods and demonstrates strong performance with small datasets by utilizing stochastic permutations of the training data, thereby improving its robustness.

Given a training subset with N samples and M features, where each sample is represented as \(({x}_{i}, {y}_{i})\), as \({x}_{i}\) is a vector of M features and \({y}_{i}\) is the corresponding target variable, CatBoost aims to learn a function \(F(x)\) that estimates the target variable \(y\)60.

where \(F\left(x\right)\) represents the overall prediction function, \({F}_{0}\left(x\right)\) is the initial guess or the baseline prediction, and \({f}_{m}({x}_{i})\) represents the prediction of the mth tree for the ith training sample.

This framework employs both symmetric and non-symmetric methods for tree construction61,62. This algorithm implements a non-symmetric splitting technique for numerical attributes, while utilizing a symmetric splitting approach for categorical attributes, evaluating all potential split points and generating a new branch for each category63. This methodology improves the GB algorithm and effectively develops a robust model by iteratively reducing training errors64. Figure 2 demonstrates a schematic representation of the CatBoost algorithm.

XGBoost

XGBoost is a powerful supervised machine learning algorithm65, combining classification and regression trees (CARTs) to improve learning dataset alignment66. XGBoost is popular due to its strong generalization abilities and differences from other boosting methods, making it effective for regression and classification problems67,68. It combines several weak classifiers/regressors into a strong classifiers/regressors using the decision tree (DT) algorithm69. XGBoost is fundamentally based on an optimized distributed GB framework. While traditional GB constructs trees in a sequential manner, XGBoost enhances this process by employing a parallelized approach to tree construction. This parallel computation occurs at a more granular level compared to bagging methods, specifically during the tree-building phase at each iteration. There are three categories of nodes in this algorithm70. As Fig. 3 presented, in each CART tuning procedure, the root node plays a crucial role, followed by the interior nodes and, finally, the leaf nodes.

During XGBoost developing process, a series of CARTs are built sequentially and each CART estimator is associated with a weight to be tuned in the training process to construct a powerful and robust result. After aggregating the tree results, the model’s initial productivity prediction is calculated as follows71:

in which, \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) denotes the predicted value, \({f}_{k}\) shows the regression tree’s output, \(T\) is a number of leaf nodes, \(q\) illustrates tree’s structure, and \(\omega\) is the weight vector.

In the context of regression tasks, XGBoost incrementally adds new regression trees, which are designed to fit the residuals produced by the preceding model through the newly constructed CART tree. The ultimate prediction is derived by aggregating the outputs of all trained DTs across each training iteration72. This paradigm proposed a simple GB method by integrating a regularization component into the objective function, which assists in reducing the risk of overfitting70,73:

where, \({y}_{i}\) and \({\widehat{y}}_{i}^{(r)}\) shows the experimental and the estimated value of the r-th step, respectively, \(L\left({y}_{i},{\widehat{y}}_{i}^{(r)}\right)\) denotes the loss function, \(n\) stands for the count of training samples, \({g}_{r}\) is the symbol for showing tree’s structure, and \(\Omega ({g}_{r})\) shows the regularization term calculated as below70:

where, ω is the weight of the leaves, T denotes the total count of leaves, while γ and λ are constant coefficients, assigned default values of 0 and 1, respectively.

RF

RF is an ensemble machine learning technique introduced in 200174, recognized for its interpretability, ease of use, and rapid computational efficiency. This robust algorithm is adept at addressing various tasks, including unsupervised learning, regression, and classification75,76. The RF methodology is built upon a collection of DTs, where each tree functions as a relatively straightforward model characterized by root nodes, split nodes, and leaf nodes. In this context, each DT is treated as an individual model output, which is then synthesized to produce a comprehensive new model77. The inherent randomness in the selection of nodes is fundamental to the RF approach. In other words, this technique integrates multiple individual learners to create a cohesive model78,79. This paradigm employs a distinctive sampling technique known as bootstrap sampling to enhance diversity of selected samples. This method generates two types of data: out-of-bag (OOB) data and in-bag data80. OOB data consists of one-third of the original sample that is excluded from the bag, while in-bag data pertains to the portion of the sample that remains within the bag (see Fig. 4)81. It operates not on a singular DT but rather aggregates predictions from multiple individual trees, determining the final response based on the majority vote among them.

When Dt is the training data for tree ht, the training dataset of the model is expressed as \(D = \left\{ {\left( {x_{1} ,y_{1} } \right),\left( {x_{2} ,y_{2} } \right),...,\left( {x_{n} ,y_{n} } \right)} \right\}\). Moreover, the following equation calculates the prediction of the OOB outcome for data × 74:

also, the error of the OOB dataset is measured as follows:

The randomness operation of the RF model is controlled by the parameter q as q = log2 d. The feature significance of the variable Xi is calculated as below74:

in which, B shows the number of trees, \({X}_{i}\) stands for the ith factor of the vector X, \(\widetilde{OOB}{err}_{{t}^{i}}\) denotes the estimation error of the OOB samples of the permuted \({X}_{i}\) sample in tree t, and \(OOB{err}_{t}\) shows initial OOB samples, that contains the permuted variables.

LightGBM

LightGBM represents an innovative GB framework that employs tree-based algorithms characterized by vertical or leaf-wise growth, in contrast to traditional algorithms that typically exhibit horizontal or level-wise growth82,83. This framework prioritizes the expansion of leaves associated with significant loss, achieving a greater reduction in loss than traditional level-wise algorithms84. Figure 5 illustrates the distinctions between level-wise and leaf-wise tree growth more effectively.

LightGBM implements three key strategies to ensure rapid, efficient, and accurate model training59. First, it adopts a leaf-wise growth strategy for constructing DTs. To enhance training efficiency and minimize the risk of overfitting, LightGBM imposes constraints on the tree’s depth and the minimum count of data required for each leaf node. The use of histogram-based methods contributes to reducing loss, accelerating training, and minimizing memory consumption85. Second, LightGBM utilizes the gradient-based one-side sampling (GOSS) technique for splitting internal nodes, which is informed by variance gain. This method reduces the count of instances with low gradients prior to calculating informative data, thereby enabling the sampling of more informative data86. It is noteworthy that the histogram-based approach is computationally more intensive than GOSS. Lastly, LightGBM incorporates exclusive feature bundling to decrease the dimensionality of input features, thereby expediting the training stage while maintaining precision87.

The following formula shows the training subset of the LightGBM paradigm88:

Then, \({\widehat{f}}_{(x)}\) will forecast by minimizing the loss function \(L\):

Finally, the training process of each tree can be presented as below88:

In the equation above, W stands for the weight term of each leaf node, q shows the decision rules used in a single tree, and N indicates the leaf number in a tree. Applying Newton’s law for minimizing objective function, the training final result of each step is computed as:

Results and discussion

Developed models

For training the intelligent algorithms, various train/test ratios such as 70/30, 75/25, 80/20, 85/15, and 90/10 are evaluated to obtain the optimum proportion. As a consequence, the dataset utilized in this work was randomly partitioned into training and testing subsets, adhering to an 80/20 proportional split as the best ratio. Moreover, to achieve robust model validation, K-fold cross-validation analysis is applied to the training data to prevent overfitting and to make reliable predictions. After testing various K values, the optimum value of 10 is earned. Hence, the dataset is divided into ten parts, with each part used as a validation set once, ensuring comprehensive model evaluation89. Additionally, grid search was applied to fine-tune the hyperparameters, selecting values grounded in both theoretical insights and practical relevance. The optimal hyperparameter values for all models are presented in Table 3.

Evaluation of developed models

The performance of the developed models was assessed applying several statistical indicators, such as the standard deviation (SD), mean absolute relative error (MARE, %), mean relative error (MRE, %), root mean square error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (R2). The formulas for the mentioned statistical metrics are defined as follows90:

here, Yi,exp stands for the experimental crude oil residue in the oxidation process, and Yi,pred shows the predicted crude oil residue by the models, and N is the count of data.

Table 4 presents the computed values for each statistical parameter during the modeling processes. Analysis of the statistical criteria in Table 4 demonstrates an accuracy ranking of the models, with CatBoost, XGBoost, RF, and LightGBM in descending order based on MARE values. Notably, the CatBoost model achieved the most accurate predictions for crude oil residue during oxidation, with MARE values of 4.95% across the entire database, 5.92% for testing collection, and 4.71% for training collection. Moreover, an R2 value of 0.9993 highlights the model’s strong predictive capability, supported by its minimal SD, RMSE, and MRE values compared to other models, underscoring its robustness in prediction.

Next, Table 5 shows the comparison of the proposed model in this work with existing models in the literature for crude oil TGA estimation. Most studies in the literature have primarily focused on modeling the pyrolysis behavior of crude oils, with comparatively fewer works addressing oxidation. Additionally, the number of data points and crude oil samples considered in these studies has generally been limited. However, this work significantly expands the data size and number of crude oil samples, achieving high prediction accuracy despite the increased dataset size.

To conduct a deeper evaluation of the suggested models’ accuracy, a graphical analysis was conducted by plotting predicted crude oil residue values versus the corresponding laboratory values, as illustrated in Fig. 6. This figure reveals a dense clustering of points near the Y = X line for all models. Nonetheless, the CatBoost model displays superior performance, exhibiting greater alignment between experimental and predicted values, which underscores its reliability for forecasting crude oil oxidation.

Subsequently, the error distribution of the models is evaluated visually, based on the premise that a model demonstrating lower error dispersion around the zero-error line in the plots indicates higher reliability. Figure 7 illustrates that the CatBoost model exhibits less error spread near the zero-error line in comparison with other models. Additionally, the absence of any discernible error trends in both the training and testing datasets highlights the accuracy and robustness of the proposed models.

To complement previous analyses, a cumulative frequency plot for the entire dataset was created for the suggested models, as shown in Fig. 8. The absolute relative error (ARE, %) was calculated by applying the formula provided in below:

Figure 8 reveals that over 70% and 90% of the crude oil residue estimates made by the CatBoost model had errors below 2.5% and 10.5%, respectively. In comparison, the RF, XGBoost, and LightGBM models showed errors of 12.43%, 16.75%, and 18.13% for 90% of the data, respectively, underscoring high reliability of the CatBoost model in predicting crude oil oxidation.

Trend analysis

Finally, CatBoost, identified as the best-performing model in this work, is evaluated by comparing its predictions of the thermo-oxidative thermal behavior trends of crude oils with laboratory data to assess its accuracy in capturing these trends. First, the impact of the heating rate on crude oil #9, with an API gravity of 16.4, is assessed and illustrated in Fig. 9. It is evident that increasing the heating rate causes a shift of reaction regions toward higher temperatures due to thermal lag, resulting in reduced mass loss at elevated heating rates49,53. Literature findings confirm that with higher heating rates, the peak, burnout, and ignition temperatures move to higher values51. In this context, the CatBoost model accurately captures the rate of mass loss of crude oil across various heating rates, demonstrating its robustness in predicting the thermo-oxidative behavior trends of crude oil.

Comparison of experimental data45 with CatBoost model predictions for TG curves of a heavy oil at various heating rates.

Figure 10 presents the TG curves for two crude oils: light oil (#17) and heavy oil (#18), plotted against temperature at a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min. Due to their distinct compositions and properties, the TG profiles of these oils vary significantly. Generally, heavier crude oils, which contain higher asphaltene and resin contents, tend to leave more residual mass54,91. The TG analysis reveals distinct mass loss patterns for light and heavy crude oils, as indicated in the literature53. Light oil undergoes a considerable mass loss of 85% in the LTO stage, almost double that of heavy oil (48.9%), while heavy oil experiences greater mass loss during the fuel deposition and HTO stages, driven by its higher asphaltene content and complex intermolecular interactions53. Again, the CatBoost model effectively captures the mass loss rates of both crude oils, demonstrating its strong predictive accuracy for oxidation behavior of crude oils.

Comparison of experimental data53 with CatBoost model predictions for TG curves of heavy and light oils at a heating rate of 10 ˚C/min.

Sensitivity analysis

In this study, sensitivity analysis based on the correlation coefficients92,93 is utilized to quantify the impact of input variables on the CatBoost model’s predictions. A higher correlation coefficient calculated between any input parameter and the output indicates a more substantial impact of that parameter on crude oil residue during oxidation. The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables. Here, the Pearson correlation coefficients are determined by applying the following equation38,94:

here, inpi,j shows the jth value of the ith input variable and inpa,i is the average of the ith input variable. Also, i can be any of the inputs considered in the modeling. Finally, the average value and the jth value of predicted crude oil residue are shown by Ya and Yj, respectively.

Moreover, the Spearman correlation coefficient is a rank-based measure that captures the strength and direction of monotonic relationships between two variables. It is resilient to outliers and can reveal nonlinear associations often missed by traditional linear methods. It is calculated using the following formula93:

here, ρ represents the Spearman rank correlation coefficient, while n is the number of observations. The terms R(x) and Rm(x) denote the rank and mean rank of the x variable, respectively, with similar definitions for R(y) and Rm(y).

The sensitivity analysis presented in Fig. 11 highlights the influence of various input parameters on residue formation in crude oils, using both Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients. Temperature stands out as the most impactful factor, showing a strong negative correlation with residue formation, with Pearson and Spearman coefficients of -0.76 and -0.93, respectively, indicating a substantial reduction in residual content as temperature increases. The difference between Pearson and Spearman coefficients indicates that temperature’s impact on residue formation involves both linear and nonlinear effects, with the latter being more pronounced. API gravity also exhibits a negative effect, with Pearson and Spearman values of -0.19 and -0.18, respectively, suggesting that lighter oils produce less residue. In contrast, asphaltene and resin have positive correlations, with Pearson coefficients of 0.16 and 0.13, and slightly higher Spearman coefficients of 0.17 and 0.16, respectively. These positive values imply that higher levels of asphaltene and resin contribute to increased residue formation. The slightly higher Spearman values indicate the potential presence of nonlinear relationships, which this rank-based method can better capture. The heating rate has a relatively minor positive impact on residue formation, with Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients of 0.032 and 0.026, respectively, indicating a weak influence. Overall, the temperature has the most substantial impact, followed by API gravity, asphaltene, resin, and heating rate in descending order of influence, emphasizing the critical role of crude oil composition and operational conditions in residue formation. Crude oil type, as well as its asphaltene and resin content, plays a critical role in influencing coke deposition, which is evident in the results of sensitivity analysis. For the ISC process to remain sustainable, managing fuel consumption and residue formation is essential. Thus, precisely calculating the amount of air injected to ignite the coke or residue within the porous media is vital to enhance the heat generated during high-temperature oxidation.

Leverage technique

The leverage technique95,96,97 is useful for identifying outliers and potentially anomalous data points that may deviate from the main dataset trends. Additionally, this technique plays an important role in evaluating the reliability and accuracy of the database used for modeling purposes. Standardized residuals (SR) are calculated as the differences between the model’s estimates and real laboratory measurements. In this calculation, ei is the error for each data point, MSE is the mean square error, and Hi denotes the leverage value for the ith observation98:

Furthermore, in this approach, leverage values, represented by the diagonal elements of the hat matrix, are calculated based on the structure of the hat matrix, as outlined in the following99:

in this context, X represents an n × i matrix that includes n data points and i input parameters, while T stands for the transpose of the matrix. Furthermore, the critical leverage (H*) is computed as follows97:

Here, data with SR within the interval [− 3, + 3] and H ≤ H* are regarded as “valid”. The model is statistically sound if the majority of data satisfy the mentioned conditions. Also, points with H > H* and − 3 ≤ R ≤ 3 are identified as “out-of-leverage” points, meaning they exist outside the applicability domain yet remain accurately predicted. In contrast, points with SR values beyond [− 3, + 3] are labeled as “suspected” points, signifying a potential for experimental uncertainty, thereby placing them outside the model’s applicability domain97,98. As illustrated in the Williams plot in Fig. 12, only 2.14% of the empirical data (i.e., 66 data points) were identified as suspected, and no out-of-leverage points were detected. This represents a minimal fraction of the dataset, indicating that the vast majority of data points were classified as valid. These findings prove that CatBoost model suggested in this work demonstrates a high level of reliability.

Conclusions

In this study, thermo-oxidative profiles and residue formation of crude oils during TGA are modeled using 3075 experimental data points collected from 18 crude oils’ oxidation, spanning an API gravity range of 5–42. Four advanced tree-based machine learning algorithms including CatBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and RF were utilized for modeling. The findings of this work allow for the following conclusions to be drawn:

-

The models were ranked in terms of accuracy, with CatBoost, XGBoost, Random Forest, and LightGBM. The CatBoost model demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy for crude oil residue during oxidation, achieving MARE values of 4.95% across the entire database, 5.92% for the testing collection, and 4.71% for the training collection. In addition, an R2 value of 0.9993 underscores the model’s exceptional predictive capability.

-

Temperature strongly influences residual crude oil content, with a significant negative correlation, while API gravity also negatively impacts it. In contrast, asphaltene, resin, and heating rate positively correlate with crude oil residual content, with temperature being the most influential factor, followed by API gravity, asphaltene, resin, and heating rate; crude oil type and composition notably affect coke deposition as shown in sensitivity analysis.

-

The leverage method identified only 2.14% of the data as suspected, with no out-of-leverage points detected, highlighting the high reliability of the CatBoost model suggested in this work.

To ensure the sustainability of the ISC process, effective management of fuel consumption and residue formation is crucial, a task in which the developed CatBoost model demonstrated exceptional capability.

Data availability

The databank utilized during this research is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Harding, T. Methods to enhance success of field application of in-situ combustion for heavy oil recovery. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 26, 190–197 (2023).

Minakov, A. V., Meshkova, V. D., Guzey, D. V. & Pryazhnikov, M. I. Recent advances in the study of in situ combustion for enhanced oil recovery. Energies 16, 4266 (2023).

Dong, X. et al. Enhanced oil recovery techniques for heavy oil and oilsands reservoirs after steam injection. Appl. Energy 239, 1190–1211 (2019).

Dong, X., Liu, H., Wu, K. & Chen, Z. in SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference? D041S018R004 (SPE).

Yang, M., Harding, T. G. & Chen, Z. Numerical investigation of the mechanisms in co-injection of steam and enriched air process using combustion tube tests. Fuel 242, 638–648 (2019).

Medina, O. E., Olmos, C., Lopera, S. H., Cortés, F. B. & Franco, C. A. Nanotechnology applied to thermal enhanced oil recovery processes: A review. Energies 12, 4671 (2019).

Ado, M. R., Greaves, M. & Rigby, S. P. Numerical simulation investigations of the applicability of THAI in situ combustion process in heavy oil reservoirs underlain by bottom water. Petrol. Res. 8, 36–43 (2023).

Turta, A., Chattopadhyay, S., Bhattacharya, R., Condrachi, A. & Hanson, W. Current status of commercial in situ combustion projects worldwide. J. Can. Pet. Technol. https://doi.org/10.2118/07-11-GE (2007).

Ursenbach, M., Moore, R. & Mehta, S. Air injection in heavy oil reservoirs-a process whose time has come (again). J. Can. Petrol. Technol. 49, 48–54 (2010).

Turta, A., Singhal, A. K., Islam, M. N. & Greaves, M. in SPE Canadian Energy Technology Conference. D011S010R002 (SPE).

Martins, M. F. Structure d’un front de combustion propagé en co-courant dans un lit fixe de schiste bitumineux broyé, Institut National Polytechnique (Toulouse), (2008).

Ismail, N. B. & Hascakir, B. Impact of asphaltenes and clay interaction on in-situ combustion performance. Fuel 268, 117358 (2020).

Xu, Q. et al. Chemical-structural properties of the coke produced by low temperature oxidation reactions during crude oil in-situ combustion. Fuel 207, 179–188 (2017).

Bhattacharya, S., Mallory, D. G., Moore, R. G., Ursenbach, M. G. & Mehta, S. A. Vapor-phase combustion in accelerating rate calorimetry for air-injection enhanced-oil-recovery processes. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 20, 669–680 (2017).

Gutiérrez, D. Development of a comprehensive and general approach to in situ combustion modelling. Development 2024, 03–26 (2024).

Bhattacharya, S., Mallory, D., Moore, R., Ursenbach, M. & Mehta, S. in SPE Western Regional Meeting. SPE-180451-MS (SPE).

Antolinez, J. D., Miri, R. & Nouri, A. In situ combustion: A comprehensive review of the current state of knowledge. Energies 16, 6306 (2023).

Mehrabi-Kalajahi, S., Varfolomeev, M. A., Sadikov, K. G., Mikhailova, A. N. & Feoktistov, D. A. The impact of the initiators on heavy oil oxidation in porous media during in situ combustion for in situ upgrading process. Energy Fuels 38, 4134–4141 (2024).

Yuan, C. et al. in SPE Kuwait Oil and Gas Show and Conference. D033S013R006 (SPE).

Belgrave, J. D., Moore, R. G., Ursenbach, M. G. & Bennion, D. W. A comprehensive approach to in-situ combustion modeling. SPE Adv. Technol. Ser. 1, 98–107 (1993).

Yamamoto, K., He, X. & Doolen, G. D. Simulation of combustion field with lattice Boltzmann method. J. Stat. Phys. 107, 367–383 (2002).

Yamamoto, K., Takada, N. & Misawa, M. Combustion simulation with Lattice Boltzmann method in a three-dimensional porous structure. Proc. Combust. Inst. 30, 1509–1515 (2005).

Xu, Q. et al. Coke formation and coupled effects on pore structure and permeability change during crude oil in situ combustion. Energy Fuels 30, 933–942 (2016).

Zhao, S., Pu, W., Peng, X., Zhang, J. & Ren, H. Low-temperature oxidation of heavy crude oil characterized by TG, DSC, GC-MS, and negative ion ESI FT-ICR MS. Energy 214, 119004 (2021).

Zhao, S., Pu, W., Pan, J., Chen, S. & Zhang, L. Thermo-oxidative characteristics and kinetics of light, heavy, and extra-heavy crude oils using accelerating rate calorimetry. Fuel 312, 123001 (2022).

Askarova, A., Popov, E., Maerle, K. & Cheremisin, A. Comparative study of in-situ combustion tests on consolidated and crushed cores. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 26, 167–179 (2023).

Cao, D. et al. Correction of linear fracture density and error analysis using underground borehole data. J. Struct. Geol. 184, 105152 (2024).

Yanchun, L. et al. Surrogate model for reservoir performance prediction with time-varying well control based on depth generative network. Pet. Explor. Dev. 51, 1287–1300 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Comparison of phenolic antioxidants’ impact on thermal oxidation stability of pentaerythritol ester insulating oil. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2024.3487148 (2024).

Li, S. et al. The hidden vulnerabilities of pentaerythritol synthetic ester insulating oil for eco-friendly transformers: A dive into molecular behavior. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2024.3510476 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Integrating experimental study and intelligent modeling of pore evolution in the Bakken during simulated thermal progression for CO2 storage goals. Appl. Energy 359, 122693 (2024).

Zhou, Y., Guan, W., Sun, Q., Zou, X. & He, Z. Effect of multi-scale rough surfaces on oil-phase trapping in fractures: Pore-scale modeling accelerated by wavelet decomposition. Comput. Geotech. 179, 106951 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. Probing the combustion characteristics of micron-sized aluminum particles enhanced with graphene fluoride. Combust. Flame 272, 113858 (2025).

Gan, B. et al. Phase transitions of CH4 hydrates in mud-bearing sediments with oceanic laminar distribution: Mechanical response and stabilization-type evolution. Fuel 380, 133185 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. Effect of coal tar components and thermal polycondensation conditions on the formation of mesophase pitch. Materials 18, 1002 (2025).

Rasouli, A., Dabiri, A. & Nezamabadi-pour, H. A multi-layer perceptron-based approach for prediction of the crude oil pyrolysis process. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 37, 1464–1472 (2015).

Norouzpour, M., Rasouli, A. R., Dabiri, A., Azdarpour, A. & Karaei, M. A. Prediction of crude oil pyrolysis process using radial basis function networks. QUID: Investigación, Ciencia Y Tecnología, 567–576 (2017).

Mohammadi, M.-R., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Schaffie, M., Husein, M. M. & Ranjbar, M. Application of cascade forward neural network and group method of data handling to modeling crude oil pyrolysis during thermal enhanced oil recovery. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 205, 108836 (2021).

Mohammadi, M.-R. et al. On the evaluation of crude oil oxidation during thermogravimetry by generalised regression neural network and gene expression programming: application to thermal enhanced oil recovery. Combust. Theor. Model. 25, 1268–1295 (2021).

Hadavimoghaddam, F. et al. Modeling crude oil pyrolysis process using advanced white-box and black-box machine learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 13, 22649 (2023).

Karimian, M., Schaffie, M. & Fazaelipoor, M. H. Estimation of the kinetic triplet for in-situ combustion of crude oil in the presence of limestone matrix. Fuel 209, 203–210 (2017).

Karimian, M., Schaffie, M. & Fazaelipoor, M. H. Determination of activation energy as a function of conversion for the oxidation of heavy and light crude oils in relation to in situ combustion. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 125, 301–311 (2016).

Li, Y.-B. et al. Low temperature oxidation characteristics analysis of ultra-heavy oil by thermal methods. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 48, 249–258 (2017).

Varfolomeev, M. A. et al. Chemical evaluation and kinetics of Siberian, north regions of Russia and Republic of Tatarstan crude oils. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 38, 1031–1038 (2016).

Pu, W., Chen, Y., Li, Y., Zou, P. & Li, D. Comparison of different kinetic models for heavy oil oxidation characteristic evaluation. Energy Fuels 31, 12665–12676 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. New insights into the oxidation behaviors of crude oils and their exothermic characteristics: Experimental study via simultaneous TGA/DSC. Fuel 219, 141–150 (2018).

Kok, M. V., Varfolomeev, M. A. & Nurgaliev, D. K. Low-temperature oxidation reactions of crude oils using TGA–DSC techniques. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 141, 775–781 (2019).

Li, Y.-B. et al. Study of the catalytic effect of copper oxide on the low-temperature oxidation of Tahe ultra-heavy oil. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 135, 3353–3362 (2019).

Yuan, C. et al. Mechanistic and kinetic insight into catalytic oxidation process of heavy oil in in-situ combustion process using copper (II) stearate as oil soluble catalyst. Fuel 284, 118981 (2021).

Zhao, S. et al. Low-temperature oxidation of light and heavy oils via thermal analysis: Kinetic analysis and temperature zone division. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 168, 246–255 (2018).

Kök, M. V., Varfolomeev, M. A. & Nurgaliev, D. K. TGA and DSC investigation of different clay mineral effects on the combustion behavior and kinetics of crude oil from Kazan region, Russia. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 200, 108364 (2021).

Yuan, C., Emelianov, D. A. & Varfolomeev, M. A. Oxidation behavior and kinetics of light, medium, and heavy crude oils characterized by thermogravimetry coupled with Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Energy Fuels 32, 5571–5580 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. The impact of the oil character and quartz sands on the thermal behavior and kinetics of crude oil. Energy 210, 118573 (2020).

Ranjbar, M. & Pusch, G. Pyrolysis and combustion kinetics of crude oils, asphaltenes and resins in relation to thermal recovery processes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 20, 185–196 (1991).

Kharazi Esfahani, P., Peiro Ahmady Langeroudy, K. & Khorsand Movaghar, M. R. Enhanced machine learning—ensemble method for estimation of oil formation volume factor at reservoir conditions. Sci. Rep. 13, 15199 (2023).

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 31 (2018).

Yu, R. et al. Ensemble learning for predicting average thermal extraction load of a hydrothermal geothermal field: A case study in Guanzhong Basin, China. Energy 296, 131146 (2024).

Pu, B. et al. Machine Learning Evaluation Method of Inter-well Sand Body Connectivity by CatBoost Model: A Field Example from Tight Oil Reservoir, Ordos Basin, China.

Kouassi, A. K. F. et al. Identification of karst cavities from 2D seismic wave impedance images based on Gradient-Boosting Decision Trees Algorithms (GBDT): Case of ordovician fracture-vuggy carbonate reservoir, Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin, China. Energies 16, 643 (2023).

Hancock, J. T. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. CatBoost for big data: An interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 7, 94 (2020).

Esfandi, T., Sadeghnejad, S. & Jafari, A. Effect of reservoir heterogeneity on well placement prediction in CO2-EOR projects using machine learning surrogate models: Benchmarking of boosting-based algorithms. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 233, 212564 (2024).

Lv, Q. et al. Modelling minimum miscibility pressure of CO2-crude oil systems using deep learning, tree-based, and thermodynamic models: Application to CO2 sequestration and enhanced oil recovery. Sep. Purif. Technol. 310, 123086 (2023).

Nakhaei-Kohani, R. et al. Extensive data analysis and modelling of carbon dioxide solubility in ionic liquids using chemical structure-based ensemble learning approaches. Fluid Phase Equilib. 585, 114166 (2024).

Liu, B. & Li, C. Mining and analysis of production characteristics data of tight gas reservoirs. Processes 11, 3159 (2023).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. in Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. 785–794.

Pan, S., Zheng, Z., Guo, Z. & Luo, H. An optimized XGBoost method for predicting reservoir porosity using petrophysical logs. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109520 (2022).

Xie, Z. et al. Prediction of conformance control performance for cyclic-steam-stimulated horizontal well using the XGBoost: A case study in the Chunfeng heavy oil reservoir. Energies 14, 8161 (2021).

Gu, Y., Zhang, D. & Bao, Z. A new data-driven predictor, PSO-XGBoost, used for permeability of tight sandstone reservoirs: A case study of member of chang 4+ 5, western Jiyuan Oilfield, Ordos Basin. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 199, 108350 (2021).

Mahdaviara, M., Sharifi, M. & Ahmadi, M. Toward evaluation and screening of the enhanced oil recovery scenarios for low permeability reservoirs using statistical and machine learning techniques. Fuel 325, 124795 (2022).

Lv, Q. et al. Modeling thermo-physical properties of hydrogen utilizing machine learning schemes: Viscosity, density, diffusivity, and thermal conductivity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 72, 1127–1142 (2024).

Dong, Y. et al. A physics-guided eXtreme gradient boosting model for predicting the initial productivity of oil wells. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 231, 212402 (2023).

Sun, H., Luo, Q., Xia, Z., Li, Y. & Yu, Y. Bottomhole pressure prediction of carbonate reservoirs using XGBoost. Processes 12, 125 (2024).

Pirizadeh, M., Alemohammad, N., Manthouri, M. & Pirizadeh, M. A new machine learning ensemble model for class imbalance problem of screening enhanced oil recovery methods. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 198, 108214 (2021).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Hidayat, F. & Astsauri, T. M. S. Applied random forest for parameter sensitivity of low salinity water Injection (LSWI) implementation on carbonate reservoir. Alex. Eng. J. 61, 2408–2417 (2022).

Rahimi, M. & Riahi, M. A. Reservoir facies classification based on random forest and geostatistics methods in an offshore oilfield. J. Appl. Geophys. 201, 104640 (2022).

Zaiery, M., Kadkhodaie, A., Arian, M. & Maleki, Z. Application of artificial neural network models and random forest algorithm for estimation of fracture intensity from petrophysical data. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 13, 1877–1887 (2023).

Guo, J. et al. Optimized random forest method for 3D evaluation of coalbed methane content using geophysical logging data. ACS Omega 9, 35769–35788 (2024).

Wang, M., Feng, D., Li, D. & Wang, J. Reservoir parameter prediction based on the neural random forest model. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 888933 (2022).

Zheng, H., Mahmoudzadeh, A., Amiri-Ramsheh, B. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Modeling viscosity of CO2–N2 gaseous mixtures using robust tree-based techniques: Extra tree, random forest, GBoost, and LightGBM. ACS Omega 8, 13863–13875 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Prediction of permeability using random forest and genetic algorithm model. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 125, 1135–1157 (2020).

Song, L. et al. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 012084 (IOP Publishing).

Shen, B. et al. A novel CO2-EOR potential evaluation method based on BO-LightGBM algorithms using hybrid feature mining. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 222, 211427 (2023).

Wang, B., Wu, D., Zhang, K., Zhang, H. & Zhang, C. prediction model of fault block reservoir measure index based on 1DCNN-LightGBM. Sci. Program. 2023, 8555423 (2023).

Liu, Y., Zhu, R., Zhai, S., Li, N. & Li, C. Lithofacies identification of shale formation based on mineral content regression using LightGBM algorithm: A case study in the Luzhou block, South Sichuan Basin, China. Energy Sci. Eng. 11, 4256–4272 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Prediction technology of a reservoir development model while drilling based on machine learning and its application. Processes 12, 975 (2024).

Kumar, I., Tripathi, B. K. & Singh, A. Synthetic well log modeling with light gradient boosting machine for Assam-Arakan Basin, India. J. Appl. Geophys. 203, 104697 (2022).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in neural information processing systems, Vol. 30 (2017).

Mohammadi, M.-R., Larestani, A., Schaffie, M., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. & Ranjbar, M. Predictive modeling of CO2 solubility in piperazine aqueous solutions using boosting algorithms for carbon capture goals. Sci. Rep. 14, 22112 (2024).

Mohammadi, M.-R. et al. Modeling the solubility of light hydrocarbon gases and their mixture in brine with machine learning and equations of state. Sci. Rep. 12, 14943 (2022).

Murugan, P., Mani, T., Mahinpey, N. & Asghari, K. The low temperature oxidation of Fosterton asphaltenes and its combustion kinetics. Fuel Process. Technol. 92, 1056–1061 (2011).

Chen, G. et al. The genetic algorithm based back propagation neural network for MMP prediction in CO2-EOR process. Fuel 126, 202–212 (2014).

Xu, M., Wong, T.-C. & Chin, K.-S. Modeling daily patient arrivals at Emergency Department and quantifying the relative importance of contributing variables using artificial neural network. Decis. Support Syst. 54, 1488–1498 (2013).

Madani, S. A. et al. Modeling of nitrogen solubility in normal alkanes using machine learning methods compared with cubic and PC-SAFT equations of state. Sci. Rep. 11, 24403 (2021).

Leroy, A. M. & Rousseeuw, P. J. Robust regression and outlier detection. rrod (1987).

Goodall, C. R. 13 Computation using the QR decomposition (1993).

Gramatica, P. Principles of QSAR models validation: Internal and external. QSAR Comb. Sci. 26, 694–701 (2007).

Lv, Q. et al. Application of group method of data handling and gene expression programming to modeling molecular diffusivity of CO2 in heavy crudes. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 237, 212789 (2024).

Rousseeuw, P. J. & Leroy, A. M. Robust Regression and Outlier Detection (John wiley & sons, Hoboken, 2005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M-R.M.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, data, Software; S-M-M.H.: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Visualization; B.A-R.: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Software; S.K.: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Software, Writing-Review & Editing; A.A.: Writing-Review & Editing, Validation, Conceptualization; A.H–S.: Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Writing-Review & Editing, Project administration; A.M.: Writing-Review & Editing, Validation, Conceptualization, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadi, MR., Hosseini, SMM., Amiri-Ramsheh, B. et al. Modeling residue formation from crude oil oxidation using tree-based machine learning approaches. Sci Rep 15, 26264 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10012-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10012-2