Abstract

Word production often involves resolving competition between multiple activated word candidates. This study investigated how cognitive control states and traits modulate lexical competition during production, combining behavioral and fMRI techniques. Cognitive control states were manipulated using a Stroop-embedded picture naming task, while lexical competition was manipulated via name agreement of pictures to be named. Cognitive control traits were measured using the AX version of the Continuous Performance, Flanker, and Simon tasks. Behaviorally, higher lexical competition was associated with worse naming responses, while Stroop conflict trials facilitated the subsequent picture naming. Neuroimaging results revealed greater activation in language-specific regions and domain-general multiple demand (MD) regions during higher lexical competition, reflecting their integrated role in managing cognitive demand. Neurally, transient cognitive control states did interact with lexical competition, albeit through competing mechanisms. Effective connectivity analyses further identified direct effects of MD regions on the activation of language regions. Additionally, individuals with lower cognitive control ability recruited additional neural domain-general resources to maintain the same level of performance as individuals with higher control ability. Overall, the results highlight how cognitive control states and traits dynamically modulate word production, through the interaction between domain-general and language networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Language production is the foundation of human communication, governed by complex cognitive and neural processes. Although recent studies have explored word production and the involvement of cognitive control1,2,3,4, the modulation effects of cognitive control states (i.e., transient trial-level processes) and traits (i.e., stable ability), along with the underlying neural mechanisms, remain poorly understood. Therefore, this study examined how cognitive control states and traits affect word production, particularly under conditions with higher lexical competition. We specifically looked at the interplay between domain-general and language-specific brain networks during production, and the temporal dynamics of these interactions. Results from this study can enhance our understanding of how the brain resolves lexical competition during production and how cognitive control modulates brain-behavior relationships during word production.

Word production is a multifaceted process involving the coordination of various functions, including retrieving lexical items, resolving competition between multiple activated word candidates, and executing articulatory plans5,6. A key challenge during this process is lexical competition7, where multiple lexical candidates are activated simultaneously, yet only one can be selected for articulation8,9. For example, when participants see a picture of “a metal container in which you can put letters for them to be collected and sent to someone else”, they might activate both “mailbox”, “letterbox”, and “postbox” (“信箱”, “郵箱” “郵筒”), as these three words are semantically equivalent. The competition among different word candidates delays naming responses and increases the likelihood of errors, especially compared to pictures with more distinct or less competitive lexical representations, for example, “lemon”10,11.

Lexical competition is often quantified through name agreement, which represents the extent to which different individuals agree on the name of a given picture. Higher name agreement indicates that the object or concept is typically associated with a single, widely recognized name, while lower name agreement indicates multiple names for the same object12,13. Name agreement is commonly operationalized using the H-index, which captures the diversity and frequency of names to an image. Specifically, the H-index is calculated through the total number of unique names provided by participants (excluding “do not know” and idiosyncratic responses) and the percentage of participants who provided each name14,15. A higher H-index indicates lower name agreement while a lower H-index indicates higher name agreement. Behavioral studies have reported that pictures with lower name agreement are associated with higher lexical competition, being named more slowly and less accurately than pictures with higher name agreement7,13,16. These challenges highlight the importance of effective cognitive control mechanisms that support conflict resolution among competing lexical candidates and facilitate fluent language production17,18,19.

Neurally, word production often involves multiple brain networks interacting dynamically7,17,20. Key language regions, such as the middle temporal gyrus (MTG), and superior temporal gyrus (STG) play crucial roles in lexical selection20,21,22,23, supporting lexical retrieval and integration for selecting appropriate words for articulation. Additionally, the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) has been recognized as a pivotal area for production that requires resolution of lexical competition24,25,26. This region has also been identified as critical for response inhibition processes, which are essential for suppressing prepotent but inappropriate representations27,28,29. The IFG is particularly sensitive to task difficulty and is frequently activated in situations with higher selection demands, highlighting its role in cognitive control and the management of interference during complex tasks24. Other domain-general cognitive control regions could facilitate managing lexical competition and resolving conflicts30. For instance, the multiple demand (MD) network, which includes bilateral frontal, anterior cingulate, and parietal cortices, is involved in various cognitively demanding tasks, including attention allocation, conflict resolution, and task switching31,32,33. During word production, MD regions are likely recruited to suppress competing words and facilitate the selection of the target word. Research has demonstrated that both language-specific and domain-general control regions work together to solve lexical competition19,34. Specifically, higher competition stimuli elicited stronger activation in the left IFG and bilateral prefrontal regions, reflecting increased demands on lexical selection and cognitive control. This engagement of both language-specific and domain-general networks highlights the integrated nature of word production, where cognitive control processes facilitate the smooth selection of target word, ensuring fluent speech.

In addition to their integral role in word production, trial-level cognitive control states and individual level cognitive control traits may modulate production performance. Cognitive control states refer to transient, task-induced changes in cognitive control, reflecting the brain’s dynamic allocation of cognitive resources to meet the demands of specific tasks or contexts35,36. The conflict-adaptation effect, also known as the Gratton effect, refers to the phenomenon where the congruency effect (the difference in response times or accuracy between congruent and incongruent trials in Stroop or Flanker task) is reduced following an incongruent trial compared to a congruent trial, illustrating how cognitive control states can modulate behavior in real time37,38. Yet, this modulation may depend on the similarity between tasks39 and the cognitive demands of tasks40. Braem proposed that conflict adaptation follows a U-shaped relationship with task dissimilarity, occurring primarily when tasks are either highly similar or entirely distinct39. In contrast, tasks with partial overlap compete for cognitive resources, making adaptation effects less evident. Although theoretically sound, the domain-general task adaptation from highly different tasks proposed by the U-shaped account has not been supported by empirical studies40. The recent learning theory of control41 further suggests that cognitive adaptation is most pronounced within the same task. While switching to a new task may induce weak across-task adaptation, it can also introduce significant interference, potentially canceling out behavioral benefits. Thus, conflict adaptation across tasks is not uniform but depends on the degree of task similarity.

Conflict adaptation has been shown across tasks, from conflict-inducing tasks to language comprehension42, such that elevated cognitive control states may directly enhance the resolution of conflicts that emerge during real-time language comprehension6,43. For instance, the Stroop task has been shown to enhance subsequent language comprehension performance, reflecting facilitation of conflict control states across tasks44. In the domain of language production, although no study has used the similar paired-design (i.e., Stroop-language pairs) as in Hsu and Novick’s study 44, recent studies using continuous alternating designs reported conflict adaptation only within-task (i.e., language to language), but not across-tasks (i.e., Task A/B to language), suggesting task-specific conflict adaptation25,45.

Individual differences in cognitive control traits can also impact language production performance46,47. For example, individuals with stronger executive function abilities are more adept at detecting and resolving conflicts46, which facilitates word retrieval47. Additionally, cognitive control traits may contribute to more efficient resolution of lexical competition43,48, and enhance adaptability to task demands46,49. Thus, understanding the role of cognitive control states and traits provides valuable insight into the variability in language production across contexts and individuals. Although some preliminary studies have investigated the effects of cognitive control states and traits individually, no study has tested them simultaneously. Additionally, the underlying neural mechanisms supporting these effects remain poorly understood.

Therefore, the current study investigated the behavioral and neural effects of cognitive control states and traits on word production. A picture naming task was used to measure word production, with stimuli varying in name agreement (higher vs. lower) to measure lexical competition. Cognitive control states were manipulated via Stroop trials (conflict vs. non-conflict) proceeding the picture trial. In addition, individual-level cognitive control traits were captured through three commonly used control tasks, namely the AX version of the Continuous Performance Task (AX-CPT)50, Flanker Task51, and Simon Task52. We hypothesized that compared to lower lexical competition pictures (i.e., higher name agreement), pictures with higher lexical competition (i.e., lower name agreement) would elicit worse behavioral performance evidenced by lower accuracy and longer response times, as well as stronger brain activation in language and cognitive control regions. Additionally, cognitive control states may modulate word production in picture naming, such that production after the Stroop conflict trials would be facilitated. The modulation of cognitive control states would also be reflected in the potential interaction between Stroop conflict conditions and the level of lexical competition. We further hypothesized that individuals with better cognitive control ability (i.e., cognitive control traits) would exhibit better performance and more efficient neural recruitment during word production.

Methods

Participants

Forty native Cantonese speakers living in Macau (16 males, mean age = 20.5 years, range = 18–27 years) were tested (Demographic information reported in Table 1). All participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were right-handed as determined by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory53. None of the participants reported a history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. All participants reported speaking at least one other language (e.g., Mandarin, English) but were all dominant in Cantonese, and lived in a Cantonese environment. Informed consent was obtained prior to the experiment, ensuring that participants were fully aware of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. All the procedures and study protocols were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Macau.

Stimuli and procedure

Neuropsychological testing was administered prior to the MRI session. During this session, participants completed a set of neuropsychological tests as well as several cognitive tasks assessing their memory, language and executive functions. Among them, three tasks were used to measure participants’ cognitive control traits: AX version of the Continuous Performance, Flanker, and Simon tasks (Table 1).

AX version of the continuous performance task

The AX version of the Continuous Performance Task has been used to measure inhibitory control58,59. During each trial, a sequence of five letters was presented at the center of the screen one at a time. The first and the last letters were targets (in red font), and the three middle letters were distractors (in white font). Unbeknownst to the participants, the target letters were divided into cue-probe pairs, forming four conditions, AX, AY, BX, and BY, respectively occupying 40%, 10%, 10%, and 40% of the trials60,61. Note that B and Y represent non-A and non-X and could be any other letters. Participants were required to press “YES” only when they saw an “X” after an “A” and press “NO” to any other letters in any other conditions. Because the AX and BY conditions were more frequent, the assumption was that the presentation of the “A” would bias participants toward a YES response, while the presentation of the “B” would bias a NO response. When an “A” was presented but followed by a “Y”, or when a “B” was presented but then followed by an “X”, it should then be difficult to suppress the bias to the more frequent response (i.e., higher inhibitory control demands). The performance difference between the conflict AY condition and the baseline AX condition can be used to measure inhibitory control.

Flanker task

The Flanker task has also been used to evaluate selective attention and inhibitory function51. In this task, participants were shown a series of stimuli consisting of a central arrow and two surrounding shapes on each side (i.e., five in total). Participants needed to respond on the keyboard to which way the center arrow was pointing (i.e., left or right). There were three conditions, the congruent condition (the central target and the surrounding arrows pointing to the same direction), the incongruent condition (the central target and the surrounding arrows pointing to different directions), and the neutral condition (the surrounding stimuli are diamond shapes instead of arrows). The flanker effect (i.e., the performance difference between the incongruent and the congruent conditions) would measure inhibitory control.

Simon task

The Simon task has also been used to measure inhibitory control through manipulating stimulus-response compatibility52. In this task, a red or blue square would show up on the left or the right side of the screen. Participants were instructed to press the right key on the keyboard for a blue square and press the left key on the keyboard for a red square. There were two conditions. In the congruent condition, the position of the square was consistent with the location of the response key (e.g., a blue square on the right side requiring a right key response). In the incongruent condition, the position of the square was inconsistent with the location of the response key (e.g., a red square on the right side requiring a left key response). During the incongruent condition, participants then need to recruit more inhibitory control to overcome the stimulus-response conflict. The Simon effect (i.e., the performance difference between incongruent and congruent conditions) would measure inhibitory control.

In-scanner word production task

After the neuropsychological session, participants completed a word production task in the MRI scanner. To manipulate the effect of cognitive control states on word production, we embedded a Stroop task in a picture naming task (Fig. 1). A total of six color words (i.e., blue, green, red, brown, orange, and yellow) and three ink colors (i.e., blue, green, and red) were used. These stimuli included congruent (i.e., word and ink color matched, “blue,” “green,” and “red” in blue, green, and red ink, respectively; Fig. 1a,c) and incongruent (i.e., word and ink color mismatched, including only response-ineligible color names, “brown,” “orange,” and “yellow” in blue, green, and red ink; Fig. 1b,d) conditions. The incongruent Stroop trials, involving solving a conflict from mismatched representations, would demand more cognitive control resources than congruent trials44,62.

In-scanner stroop-embedded picture naming task examples. In each pair, the stroop trial, then the picture were presented sequentially on a white background for 1.5 s each, separated by a blank screen for 0.5 s. A variable duration of fixation between pairs (ISI, range = 2.5–16.5 s, average ISI = 4.1 s) was used. Stroop trials in a, c are blue printed in blue, in b, d are brown printed in blue; pictures in a, b are lower lexical competition (H-index: 0.29 ± 0.22), in c, d are higher lexical competition (H-index: 1.35 ± 0.32).

Pictures for naming tasks were selected from the MultiPic norm63. The norm consists of 750 colored line drawings illustrating concrete concepts. An independent group of 53 healthy, native Cantonese speakers was recruited to norm these stimuli. They were asked to provide the most appropriate name in Cantonese as well as to rate the familiarity of each picture on a 1-100 scale. The name agreement of each picture was then calculated using the H-index14. Among these pictures, 100 items with lower name agreement were selected to elicit higher lexical competition, while 100 items with higher name agreement were selected to elicit lower lexical competition.

By presenting Stroop trials before the picture naming trials, the states of cognitive control can be modulated (i.e., conflict requiring higher cognitive control states vs. non-conflict requiring lower cognitive control states). To this end, a 2 (Conflict status: conflict vs. non-conflict) × 2 (Lexical competition: higher vs. lower) within-subject design was formed. The final set included 50 pictures for each of the four conditions. The name agreement in the higher lexical competition conditions was significantly lower than the lower lexical competition conditions (p < 0.001). Stimuli across conditions were statistically matched on familiarity, target word length, visual complexity, and word frequency (ps > 0.05). An additional 50 pictures were selected for the control condition. Different from the critical conditions that contain all Stroop-Picture pairs, the control condition includes Stroop-Stroop, Picture-Picture, and Picture-Stroop trials to prevent participants from predicting upcoming trials or task types. In each pair of all conditions, both stimuli were presented on a white background for 1.5 s, separated by a blank screen for 0.5 s (Fig. 1). A variable inter-stimuli interval after each pair (ISI, range = 2.5–16.5 s, average ISI = 4.1 s) was used, generated by the optseq2 program, as jittered presentations can optimize the hemodynamic response64.

Before scanning, participants practiced the task while minimizing head movement in an MRI simulator. After practice, participants completed 5 runs of picture naming tasks in the scanner, each containing 10 stimulus pairs from each condition. Picture stimuli were not repeated across conditions. Before each picture, participants were presented with a Stroop trial, where they needed to say the ink color of a color word in Cantonese (e.g., say “blue” for the word brown printed in blue ink). During the picture trial, participants were presented with pictures and instructed to overtly name the picture in Cantonese as quickly and accurately as possible. The overt verbal responses during the scan were recorded and online filtered using an MR-compatible fiber optic microphone system (Optoacoustics Ltd., Or-Yehuda, Israel).

Acquisition of MRI data

MRI scanning was completed using a 3T Siemens Prisma MRI scanner equipped with a 32-channel head coil. A sagittal T1-weighted localizer was first acquired to define a volume for succeeding data collection, high-order shimming, and alignment to the AC-PC line (i.e., Anterior and Posterior Commissure). Then T1-weighted anatomical images were collected using the magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MP-RAGE) sequence (repetition time [TR] = 2300 ms; echo time [TE] = 2.28 ms; flip angle = 8°; field of view [FOV] = 256 mm2; voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm; phase encode direction: anterior to posterior; fat saturation = off; duration = 5 min and 21 s).

After the structural images were obtained, participants underwent task runs in the scanner. Task-based functional images sensitive to BOLD contrast were acquired using an echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (TR = 2000 ms; TE = 25.0 ms; flip angle = 90°; FOV = 240 mm2; voxel size = 3.0 × 3.0 × 4.0 mm; 33 contiguous slices; phase encode direction: anterior to posterior; fat saturation = on; duration = 6 min and 9 s per run; 5 runs).

A field map sequence was also acquired using an echo sequence (TR = 436 ms; TE1 = 4.92 ms; TE2 = 7.38 ms; flip angle = 60°; FOV = 240 mm2; voxel size = 3.0 × 3.0 × 4.0 mm; 33 contiguous slices; phase encoding = anterior to posterior; fat saturation = off; duration = 1 min and 12 s), generating two magnitude images and one phase image.

Behavioral data coding

Responses for the Stroop-embedded picture naming task were coded based on the recordings during the scan. For each run, the participant’s verbal responses were transcribed precisely, and the accuracy of each response was assessed. For Stroop stimuli, responses were coded correct only if participants accurately said the ink color. All other responses, including omissions, were coded as incorrect. For picture stimuli, responses were coded as correct if they were exactly the same as the target word (e.g., “mailbox” for mailbox) or they described the same concept (e.g., “letterbox” for mailbox); If the produced word was not consistent with the picture concept (e.g., “door” for mailbox) or not aligned with specific concepts (e.g., “box” for mailbox), the responses were coded as incorrect. Both stimuli in a Stroop-Picture pair must be correctly responded to for the trial to be considered correct. Reaction times (RTs) for all trials were calculated using customized PRAAT scripts, by calculating the interval between the onset of the stimulus and the initiation of the verbal response.

MRI data preprocessing

Preceding data processing, the data quality was evaluated using the fBIRN QA tool65, assessing the mean signal fluctuation to noise ratio (SFNR), the number of potentially clipped voxels, and variation per slice. Subsequently, the anatomical and functional images were visually checked for artifacts and signal drop-out. The non-brain portions of the anatomical images were identified and discarded using Optimized Brain Extraction for Pathological Brains66. Preprocessing and statistical analyses were conducted using the FEAT (fMRI expert analysis tool) version 6.067,68. Preprocessing included motion correction69, B0 unwarping, slice timing correction, spatial smoothing (FWHM = 5 mm), highpass temporal filtering, coregistration, and normalization. All processed datasets were aligned to each participant’s anatomical scan and then to the MNI standard space. For modeling the BOLD signal for each event, a double-gamma hemodynamic response function was used, including only correct trials in the analyses.

Effects of cognitive control states on production

Behavioral and fMRI data analysis

Reaction time data for the Stroop-embedded picture naming task was trimmed first. Only reaction times from the correctly responded trials and within the 2.5 standard deviation range were included in the analysis. After trimming, reaction times and accuracy were analyzed as the dependent variable through a mixed-effect regression conducted in the R statistical environment (R version 4.2.270), with cognitive control states (conflict vs. non-conflict), lexical competition (higher vs. lower), and their interaction included as independent variables.

For the basic set of fMRI activation analysis, events were time-locked to the onset of each Stroop trial and each picture, enabling precise measurement of brain activity associated with word production. For preprocessed fMRI data, first-level analyses were performed on the individual runs for each participant. Higher-level group analyses were then conducted to combine first-level results across runs and then across subjects. Although the activation associated with Stroop processing was modeled, we primarily focused on brain activation associated with picture naming. We modeled the effects of cognitive control state (conflict vs. non-conflict Stroop trials), lexical competition (higher vs. lower name agreement), and their interaction on the BOLD response during picture naming using a general linear model in FSL. Instead of directly testing for interactions, we focused on characterizing differences in activation patterns following conflict and non-conflict trials, consistent with previous work using similar paradigms71. All contrasts between conditions were masked with regions corresponding to the subtracted condition to ensure that the reported regions are functionally meaningful.

In addition to the whole brain approach looking at picture-evoked fMRI activation, we further explored the time dynamics in the Stroop-Picture sequence. For this exploration, we used a Region-Of-Interest (ROI) approach that focused specifically on language processing and multiple-demand (MD) networks established from previous studies4,31,72. Coordinate locations can be found in Table 2 and 4 mm radius sphere nodes were created centering around these locations. To explore whether the involvement of MD regions would modulate the involvement of language regions, and whether this modulation is different across different task conditions, an effective connectivity analysis was conducted, using the Group Iterative Multiple Model Estimation (GIMME) method. Traditional dynamic approaches often rely on group-level models, which may fail to account for individual variability in brain processes73. By incorporating individual-level data, GIMME allows for a more nuanced understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying word production, particularly in the context of lexical competition and cognitive control74.

Behavioral results

A mixed-effect regression was conducted on picture naming accuracy and response time to explore how cognitive control states and lexical competition impact word production. On accuracy (Fig. 2a), the main effect of lexical competition was significant (β = 0.68, SE = 0.07, z = 10.19, p < 0.001), such that pictures with lower lexical competition were responded to more accurately than those with higher lexical competition. Yet, the main effect of cognitive control states (β = 0.11, SE = 0.06, z = 1.80, p = 0.07) and its interaction with lexical competition were not significant (β = -0.08, SE = 0.09, z = -0.94, p = 0.35). Additionally, congruency sequence effects (CSE) were calculated and analyzed by directly comparing the lexical competition effect following Stroop conflict condition vs. following Stroop non-conflict condition. Results showed no significant CSE on accuracy (t (39) = -0.83, p = 0.41).

On reaction time (Fig. 2b), the main effect of lexical competition was significant (β = -67.64, SE = 5.92, t (114.59) = -11.41, p < 0.001), such that pictures with lower lexical competition were responded to faster than those with higher competition. The main effect of cognitive control states was also significant (β = 14.43, SE = 6.53, t (100.62) = 2.21, p = 0.03), such that pictures after the Stroop conflict trials were responded to faster compared to the pictures after the Stroop non-conflict trials. The interaction between cognitive control states and lexical competition was not significant (β = 0.02, SE = 7.68, t (560.78) = 0.003, p = 0.998). Additionally, there was no significant CSE found on RT (t (39) = -0.02, p = 0.99). Overall, behavioral results indicated an interference effect from lexical competition and a facilitation effect on naming following Stroop conflict trials, but no evidence for conflict adaptation.

Behavioral effects of cognitive control states and lexical competition on picture naming. (a) shows a significant main effect of lexical competition on accuracy, (b) shows significant main effects of lexical competition and cognitive control states on response times, (c) shows no significant congruency sequence effect on accuracy, (d) shows no significant congruency sequence effect on response times. Error bars represent mean ± standard error (SE). Values in (c, d) represent the differences in accuracy and response times between the higher and lower lexical competition conditions.

fMRI basic activation

We first examined the effects on brain activation during picture naming by the cognitive control states, lexical competition, and their interaction. While the main effect of the cognitive control states was not found in any region, the main effect of lexical competition was significant in several regions. Specifically, when comparing with the lower lexical competition pictures, the higher lexical competition pictures elicited stronger activation in left superior frontal gyrus (SFG), extending to bilateral inferior frontal gyri (IFG) and left middle frontal gyrus (MFG), and left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), lateral occipital cortex (Fig. 3a; Table 3). And when comparing with the higher lexical competition pictures, the lower lexical competition pictures elicited stronger activation in the right lateral occipital cortex, extending to precuneus and angular gyrus (Fig. 3b; Table 3).

Furthermore, we explored the interaction between cognitive control states and lexical competition (Fig. 3c-3f; Table 3). We found that following the Stroop conflict trials, higher lexical competition pictures elicited stronger activation than lower lexical competition pictures in left IFG, extending to left SFG and left MTG (Fig. 3c), while following non-conflict trials, higher lexical competition pictures elicited stronger activation than lower lexical competition pictures in left IFG, extending to left SFG and left MFG (Fig. 3e). Following the Stroop conflict trials, lower lexical competition pictures elicited stronger activation than higher lexical competition pictures in right lateral occipital cortex, precuneus, and angular gyrus (Fig. 3d). Following the Stroop non-conflict trials, pictures with lower lexical competition elicited stronger activation in right occipital pole extending to precuneous (Fig. 3f).

(a) Regions showing stronger activation for higher lexical competition pictures than lower lexical competition pictures; (b) Regions showing stronger activation for lower lexical competition pictures than higher lexical competition pictures; (c) Regions showing stronger activation in higher lexical competition pictures than lower lexical competition pictures following Stroop conflict trials; (d) Regions showing stronger activation in lower lexical competition pictures than higher lexical competition pictures following Stroop conflict trials; (e) Regions showing stronger activation in higher lexical competition pictures than lower lexical competition pictures following Stroop non-conflict trials; (f) Regions showing stronger activation in lower lexical competition pictures than higher lexical competition pictures following Stroop non-conflict trials. HLC Higher lexical competition, LLC Lower lexical competition.

Effective connectivity analysis on language and MD regions

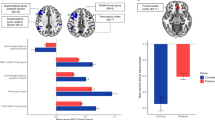

To explore the dynamic relationship between domain-general MD regions and the later language regions (Fig. 4a), and how this relationship varies across different conditions, an effective connectivity analysis was conducted. At the group level, significant connectivity patterns were identified within both MD regions and language regions, as well as from MD to language regions (Fig. 4b). Specifically, the right superior frontal gyrus and the right pars opercular of the IFG were found to drive the activation in the left anterior parietal region, which in turn influenced the activation of the left lateral occipital node (Fig. 4c). Moreover, the right pars opercular of the IFG directly activated the left pars triangular of the IFG, further influencing the activation of the left lateral occipital node (Fig. 4d). Similarly, the right middle parietal node exerted a direct influence on the posterior MTG, further driving the activation of the left pars triangular of the IFG (Fig. 4e). Statistical analyses of these paths showed no significant differences in strength across different conditions (ps > 0.05). Thus, the effective connectivity analysis revealed that activation in language regions was modulated by multiple control regions, with minimal variation across experimental conditions.

The group-level effective connectivity patterns across different conditions (a) MD network ROIs (yellow) and language network ROIs (blue) used. (b) Effective connectivity identified within MD regions, within language regions, and between MD and language regions; Colored thick lines represent the group-level dynamic paths and arrows indicate the directionality of the relationship (e.g., one node influencing another). (c, d, e) demonstrated significant pathways between MD and language nodes. Three pathways between MD and language regions were indicated by orange, blue, and green respectively.

Effects of cognitive control traits on production

Behavioral and fMRI data analysis

Cognitive control traits were captured through three cognitive tasks, namely the AX-CPT, the Flanker task, and the Simon task. Response accuracy for all three tasks was higher than 80%, indicating sufficient level of performance. Using the same criteria to the picture naming task, all reaction times were trimmed first. Then for each participant, conditional level mean RTs were calculated, then the cognitive control index was calculated for each task (i.e., AY-AX in AX-CPT, Flanker effect in Flanker task, and Simon effect in Simon task; Table 1). To gather an overall cognitive control traits indicator for each participant, indices from each task were first transformed to a Z score, then added together as a summed Z (i.e., Traits Z score). Higher Z scores indicate worse cognitive control traits (i.e., lower cognitive control ability). Reaction time and accuracy were analyzed as dependent variables using mixed-effect regression modeling, including cognitive control traits Z score as a continuous between-participant variable, lexical competition as a categorical within-subject variable, and their interaction as independent variables in the R environment (R version 4.2.2, RStudio Team, 2022).

For fMRI data analysis, the cognitive control traits Z scores were first mean-centered then added as a participant-level EV (Explanatory Variable) to the statistical matrix as a continuous regressor, investigating the main effect of cognitive control traits and its interaction with lexical competition in the higher-level analysis. The mean-centered Z-scores were multiplied by lexical competition levels to form the interaction term, which was then added as a separate EV in the design matrix. Since this set of analysis focused on the interplay between cognitive control traits and lexical competition (i.e., time locked to the onset of pictures), no further time course analysis was conducted.

Behavioral results

A mixed-effect regression was conducted on accuracy and reaction time to explore the effect of cognitive control traits, lexical competition, and their interaction. On accuracy, the main effect of lexical competition was still significant (Fig. 2a), as previously reported (β = 0.68, SE = 0.07, z = 10.19, p < 0.001), such that pictures with lower lexical competition were responded to more accurately than those with higher lexical competition. The main effect of cognitive control traits and its interaction with lexical competition were not significant (ps > 0.05). On response time, the main effect of lexical competition was significant (β = -67.65, SE = 5.93, t (114.59) = -11.41, p < 0.001; Fig. 2b). Specifically, items with lower lexical competition were responded to more quickly than those with higher lexical competition, indicating that increased lexical interference made production more difficult. Yet, the main effect of cognitive control traits and its interaction with lexical competition were not significant (ps > 0.05). Overall, these findings further highlight the strong influence of lexical competition on word production performance, independent of individual differences in cognitive control traits.

fMRI activation

On brain activation during word production, we investigated the main effects of lexical competition and cognitive control traits, as well as their interaction. In addition to the main effect of lexical competition as reported earlier (Fig. 3a,b), there was a significant effect of cognitive control traits on brain activation (Fig. 5; Table 4). Specifically, individuals with lower control ability (i.e., higher traits Z scores) demonstrated stronger activation in bilateral middle frontal gyri extending to bilateral inferior frontal gyri and bilateral precentral gyri, and left occipital cortex. In contrast, individuals with higher control ability (i.e., lower traits Z scores) exhibited stronger activation in left inferior temporal gyrus and left orbital cortex.

Main effect of cognitive control traits during picture naming. (a) Regions shown are where individuals with lower control ability (i.e., higher traits Z score) showed stronger activation; (b) Regions shown are where individuals with higher control ability (i.e., lower traits Z score) showed stronger activation.

Discussion and conclusion

The current study examined how cognitive control states and traits influence word production, particularly during higher lexical competition. Our findings revealed a reliable interference effect of lexical competition, observed both behaviorally and neurally, in the process of word production during picture naming. Cognitive control states, manipulated via a preceding Stroop trial, promoted the subsequent naming performance behaviorally, whereas the effect of lexical competition on naming was not modulated by control states. However, the control states interacted with lexical competition at the neural level, as reflected in condition-dependent activation patterns following conflict and non-conflict trials (Fig. 3c,f). Although cognitive control traits did not significantly affect behavior, individuals with lower cognitive control ability recruited additional neural resources related to cognitive control to maintain performance. Below, we discuss these findings in detail.

First, by manipulating the name agreement of pictures, we found a significant interference effect of lexical competition on word production. Specifically, items with higher lexical competition were associated with lower accuracy, longer response time, and stronger brain activation in regions involved in language processing and cognitive control. Our study observed the increased activation of bilateral IFG in solving lexical competition. This aligns with previous studies reporting more effortful processing for lower name agreement pictures than higher name agreement pictures, reflected by worse behavioral performance and stronger activation in left IFG and ERP components (e.g., P1, N2) in frontal and parietal clusters75. Beyond the involvement of bilateral IFG in addressing lexical competition20,22,76, our study revealed stronger activation in left prefrontal regions such as superior and middle frontal gyri in response to higher lexical competition. The left middle frontal gyrus (LMFG) is speculated to support the maintenance of perceptual information77, as well as the deep frontal pathway connecting the superior frontal gyrus (SFG) to Broca’s area is identified to be associated with language functions78. These regions have been consistently found in the hard > easy contrast across tasks31, indicating their role in domain-general cognitive control processes. The stronger activation of these regions in higher lexical competition condition demonstrates the involvement of domain-general control resources in solving lexical competition in word production.

Given the critical role of cognitive control in resolving lexical competition during word production, this study further examined how cognitive control states and traits modulate this process. Behaviorally, although picture naming speed was faster following Stroop conflict trials than following Stroop non-conflict trials (i.e., main effect), no significant interaction between control states and lexical competition was observed, providing no direct evidence for conflict modulation across the Stroop-picture pairs. This is surprising, as previous studies using similar paradigms have reported cross-task conflict adaptation in language comprehension44. However, our findings align with studies on production but using continuous alternating designs25,45, which have shown task-specific adaptive control rather than across-task conflict adaptation. If anything, we observed a non-significant “anti-adaptation” trend, where lexical competition effects were larger following Stroop conflict trials than non-conflict trials (Fig. 2). Braem and colleagues proposed a U-shaped relationship between task dissimilarity and conflict adaptation39, such that only tasks that are either highly similar or dissimilar show adaptation effects. For tasks with partial overlap—such as Stroop and picture naming, which both involve production but differ in stimulus modality (words vs. pictures)79 — across-task interference may arise due to competition for cognitive resources. Unlike comprehension, language production likely demands greater cognitive resources; if these resources remain engaged in the previous task, they may interfere with subsequent production rather than facilitating adaptation. The interpretation aligns with the recent learning theory of control, which posits that cognitive control strengthens task-specific connections41, leading to benefits that are limited to the same task and may even cause interference for new tasks. Consequently, weak across-task adaptation may coexist with resource competition, yielding unstable or null behavioral outcomes. Fortunately, neural mechanisms can reveal these underlying processes.

Neuroimaging results showed that, compared to non-conflict Stroop trials, picture naming following conflict trials elicited greater activation in the left superior, middle, and inferior frontal regions, as well as the left middle and inferior temporal gyri extending to the bilateral occipital cortex—particularly under higher lexical competition. This suggests that while weak across-task adaptation may exist, it is overshadowed by resource limitations from the preceding Stroop task. Thus, when processing higher competition pictures, additional neural resources are recruited to compensate for behavioral demands.

One might argue that control adaptation is simply absent in such paradigms. However, a small portion of right angular gyrus and precuneous showed stronger activation for lower-competition than higher-competition pictures, with this contrast being amplified after conflict trials. This finding does not contradict the Gratton effect38,80. Specifically, conflict resolution in the Stroop task may trigger a heightened cognitive control state41,79, preparing the brain to handle interference25. Although this adaptation did not facilitate lexical competition resolution due to across-task interference, it manifested in the lower > higher lexical competition contrast after conflict trials. Processing lower-competition pictures requires minimal cognitive control, which may misalign with the brain’s heightened control state following conflict Stroop trials. This mismatch can lead to an overallocation of resources compared to non-conflict trials. Consequently, the stronger activation observed for low-competition pictures after conflict Stroop trials suggests less efficient neural resource reallocation, potentially contributing to poorer behavioral performance (Fig. 3d). Overall, these results support the notion that transient cognitive control states influence language production. However, competing mechanisms — facilitation from conflict adaptation and interference from across-task resource competition — may explain the lack of behavioral interaction.

In addition to the observations on basic fMRI activation, follow-up effective connectivity analyses further demonstrated the relationship between domain-general control and language regions. Although this method was not sensitive to the different rapid event-related control conditions81, several control regions were found to drive the activation of language regions through distinct pathways across all conditions. Importantly, no path was identified starting from language regions to control regions. The analysis reinforced the idea that cognitive control states involving control regions can modulate subsequent language production involving language regions.

In addition to the effects of cognitive control states, we also examined the relationship between cognitive control traits and word production. Behaviorally, there was no significant effect of cognitive control traits on the naming behavior. This result aligns with the learning theory of control such that the task adaptation and control transfer are task-specific rather than domain-general41, therefore, no effect was found from domain-general control ability to language specific production. Yet, neurally, participants with lower cognitive control ability exhibited stronger activation in domain-general regions, such as the bilateral inferior frontal gyri72,82,83, middle frontal and precentral gyri72, compared to those with higher control ability. Specifically, individuals with lower cognitive control may rely more heavily on cognitive control resources to help with their performance in language production. This compensatory mechanism suggests that individuals with lower control ability recruit additional neural resources to achieve the same level of word production performance, thereby lacking any observable behavioral effects associated with the trait Z score.

While our findings provide evidence for the modulation effect of cognitive control states and traits on general language production, several potential limitations should be acknowledged. First, all participants in our study were multilinguals, which may have heightened the involvement of cognitive control mechanisms related to monolinguals. Even though the task was conducted in participants’ native language, multilinguals are known to engage cognitive control resources more intensively during language processing84. Future research should investigate whether similar effects can be observed in monolingual populations to better understand the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, while our name agreement manipulation for lexical competition proved effective, future studies could explore other aspects of competition during production, such as semantic competition.

In conclusion, the current study provides novel insights into the dynamic interaction between cognitive control and lexical competition during word production. Processing higher lexical competition pictures is more demanding than lower lexical competition pictures. While no behavioral interaction was observed, neural evidence suggests that transient cognitive control states influence lexical competition resolution, albeit through competing mechanisms. The findings align with theories proposing task-specific adaptation and resource competition, suggesting that across-task interference may counteract facilitation effects. From a sustained trait perspective, individuals with lower cognitive control ability compensate by engaging additional domain-general neural resources to maintain performance. By integrating behavioral and neural data, our study provides new insights into the dynamic role of cognitive control in language production and underscores the need for further research to disentangle the facilitatory and inhibitory effects of cross-task adaptation.

Data availability

The behavioral data presented in this study and analysis scripts are openly available on the OSF Platform at https://osf.io/mwxsc/?view_only=d08d14d0bb3143f4afeabea3f3a68de2. Imaging data are available upon request to haoyunzhang@um.edu.mo.

References

Laganaro, M. et al. Functional and time-course changes in single word production from childhood to adulthood. Neuroimage 111, 204–214 (2015).

Atanasova, T. et al. Dynamics of word production in the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Neurobiol. Lang. (Camb). 2 (1), 1–21 (2021).

Fedorenko, E. & Thompson-Schill, S. L. Reworking the Language network. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18 (3), 120–126 (2014).

Zhang, H. & Diaz, M. T. Task difficulty modulates age-related differences in functional connectivity during word production. Brain Lang. 240, 105263 (2023).

Thompson-Schill, S. L., Bedny, M. & Goldberg, R. F. The frontal lobes and the regulation of mental activity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15 (2), 219–224 (2005).

Badre, D. & Wagner, A. D. Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the cognitive control of memory. Neuropsychologia 45 (13), 2883–2901 (2007).

Britt, A. E., Ferrara, C. & Mirman, D. Distinct effects of lexical and semantic competition during picture naming in younger adults, older adults, and people with aphasia. Front. Psychol. 7, 813 (2016).

Maxfield, N. D. Inhibitory control of lexical selection in adults who stutter. J. Fluen. Disord. 66, 105780 (2020).

Moss, H. E. et al. Selecting among competing alternatives: selection and retrieval in the left inferior frontal gyrus. Cereb. Cortex. 15 (11), 1723–1735 (2005).

Apfelbaum, K. S. et al. The development of lexical competition in written- and spoken-word recognition. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Hove). 76 (1), 196–219 (2023).

Zhang, X. & Samuel, A. G. Is speech recognition automatic? Lexical competition, but not initial lexical access, requires cognitive resources. J. Mem. Lang. 100, 32–50 (2018).

Zhong, J. et al. Standardizing norms for 1286 colored pictures in Cantonese. Behav. Res. Methods. 56 (6), 6318–6331 (2024).

Alario, F. X. et al. Predictors of picture naming speed. Behav. Res. Methods Instr. Comput. 36 (1), 140–155. (2004).

Brodeur, M. B., Guerard, K. & Bouras, M. Bank of standardized stimuli (BOSS) phase II: 930 new normative photos. PLoS One. 9 (9), e106953 (2014).

Snodgrass, J. G. & Vanderwart, M. L. A standardized set of 260 pictures: norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 6 (2), 174–215 (1980).

Swingley, D. & Aslin, R. N. Lexical competition in young children’s word learning. Cogn. Psychol. 54 (2), 99–132 (2007).

Nozari, N. & Novick, J. Monitoring and control in Language production. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26 (5), 403–410 (2017).

Nozari, N., Dell, G. S. & Schwartz, M. F. Is comprehension necessary for error detection? A conflict-based account of monitoring in speech production. Cogn. Psychol. 63 (1), 1–33 (2011).

Piai, V. et al. Distinct patterns of brain activity characterise lexical activation and competition in spoken word production. PLoS One. 9 (2), e88674 (2014).

Nozari, N. & Pinet, S. A critical review of the behavioral, neuroimaging, and electrophysiological studies of co-activation of representations during word production. J. Neurolinguistics 53. (2020).

Wernicke, C. Der Aphasische Symptomenkomplex, in Der Aphasische Symptomencomplex: Eine Psychologische Studie Auf Anatomischer Basis 1–70 (Springer, 1974).

Binder, J. R. et al. Human brain Language areas identified by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurosci. 17 (1), 353–362 (1997).

Broca, P. Remarques Sur Le siège de La faculté du Langage articulé, suivies d’une observation d’aphémie (perte de La parole). Bull. Et Memoires De La. Societe Anatomique De Paris. 6, 330–357 (1861).

Nozari, N. The neural basis of word production. In The Oxford Handbook of the Mental Lexicon A. Papafragou, J.C. Trueswell, and L.R. Gleitman, Editors. (Oxford University Press, 2022).

Freund, M. & Nozari, N. Is adaptive control in Language production mediated by learning? Cognition 176, 107–130 (2018).

Nozari, N. & Thompson-Schill, S. L. Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex in processing of words and sentences. In Neurobiol. Lang. 569–584. (2016).

Badre, D. Cognitive control, hierarchy, and the rostro-caudal organization of the frontal lobes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12 (5), 193–200 (2008).

Novick, J. M., Trueswell, J. C. & Thompson-Schill, S. L. Cognitive control and parsing: Reexamining the role of Broca’s area in sentence comprehension. Cogn. Aff. Behav. Neurosci. 5 (3), 263–281. (2005).

Swick, D. et al. Left inferior frontal gyrus is critical for response Inhibition. BMC Neurosci. 9 (1), 102 (2008).

Geranmayeh, F. et al. Overlapping networks engaged during spoken Language production and its cognitive control. J. Neurosci. 34 (26), 8728–8740 (2014).

Fedorenko, E., Duncan, J. & Kanwisher, N. Broad domain generality in focal regions of frontal and parietal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110 (41), 16616–16621 (2013).

Cabeza, R. & Nyberg, L. Imaging cognition II: an empirical review of 275 PET and fMRI studies. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12 (1), 1–47 (2000).

Duncan, J. The multiple-demand (MD) system of the primate brain: mental programs for intelligent behaviour. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14 (4), 172–179 (2010).

Seo, R., Stocco, A. & Prat, C. S. The bilingual Language network: differential involvement of anterior cingulate, basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex in preparation, monitoring, and execution. Neuroimage 174, 44–56 (2018).

Maki-Marttunen, V., Hagen, T. & Espeseth, T. Task context load induces reactive cognitive control: an fMRI study on cortical and brain stem activity. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 19 (4), 945–965 (2019).

Menon, V. & D’Esposito, M. The role of PFC networks in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 47 (1), 90–103 (2022).

Yeung, N. (2013).

Gratton, G., Coles, M. G. H. & Donchin, E. Optimizing the use of information: strategic control of activation of responses. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 121, 26 (1992).

Braem, S. et al. What determines the specificity of conflict adaptation? A review, critical analysis, and proposed synthesis. Front. Psychol. 5, 1134 (2014).

Zhu, D. et al. Cognitive control is task specific: Further evidence against the idea of domain-general conflict adaptation. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Memory Cogn. (2025).

Nozari, N. Monitoring, control and repair in word production. Nat. Reviews Psychol. 4 (3), 222–238 (2025).

Ness, T. et al. The state of cognitive control in Language processing. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 17456916231197122, p (2023).

Ye, Z. & Zhou, X. Executive control in Language processing. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 33 (8), 1168–1177 (2009).

Hsu, N. S. & Novick, J. M. Dynamic engagement of cognitive control modulates recovery from misinterpretation during Real-Time Language processing. Psychol. Sci. 27 (4), 572–582 (2016).

Zhu, D. et al. Cognitive control is task specific: Further evidence against the idea of domain-general conflict adaptation. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Memory Cogn., (2025).

Salig, L. K. et al. Moving from bilingual traits to states: Understanding cognition and Language processing through Moment-to-Moment variation. Neurobiol. Lang. (Camb). 2 (4), 487–512 (2021).

Crowther, J. E. & Martin, R. C. Lexical selection in the semantically blocked Cyclic naming task: the role of cognitive control and learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 9 (2014).

Badre, D. et al. Dissociable controlled retrieval and generalized selection mechanisms in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuron 47 (6), 907–918 (2005).

Novick, J. M., Trueswell, J. C. & Thompson-Schill, S. L. Broca’s area and Language processing: evidence for the cognitive control connection. Lang. Linguistics Compass. 4 (10), 906–924 (2010).

Rosvold, H. E., Mirsky, A. F., Sarason, I., Bransome, E. D. & Beck, L. H. A continuous performance test of brain damage. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 20, 8 (1956).

Eriksen, B. A. & Eriksen, C. W. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Percept. Psychophys. 16 7 (1974).

Simon, J. R. & Wolf, J. D. Choice reaction time as a function of angular stimulus-response correspondence and age. Ergonomics 6 (1), 99–105 (1963).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9 (1), 97–113 (1971).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler Memory scale-revised. Psychol. Corp. (1987).

Gong, Y. Wechsler Adult Intelligence scale-revised in China Version (Hunan Medical College, 1992).

Acheson, D. J., Wells, J. B. & MacDonald, M. C. New and updated tests of print exposure and reading abilities in college students. Behav. Res. Methods. 40 (1), 278–289 (2008).

Patterson, J. Controlled oral word association test, in Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology, J.S. Kreutzer, J. DeLuca, and B. Caplan, Editors. Springer New York: New York, NY. 703–706. (2011).

Paxton, J. L. et al. Cognitive control, goal maintenance, and prefrontal function in healthy aging. Cereb. Cortex. 18 (5), 1010–1028 (2008).

Braver, T. S. et al. Flexible neural mechanisms of cognitive control within human prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106 (18), 7351–7356 (2009).

Gonthier, C. et al. Inducing proactive control shifts in the AX-CPT. Front. Psychol. 7, 1822 (2016).

Richmond, L. L., Redick, T. S. & Braver, T. S. Remembering to prepare: the benefits (and costs) of high working memory capacity. J. Experimental Psychology: Learn. Memory Cognition. 41 (6), 1764 (2015).

Milham, M. P. et al. The relative involvement of anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex in attentional control depends on nature of conflict. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 12 (3), 467–473 (2001).

Duñabeitia, J. A. et al. MultiPic: A standardized set of 750 drawings with norms for six European languages. Q. J. Experimental Psychol. 71 (4), 808–816 (2018).

Dale, A. M. Optimal experimental design for event-related fMRI. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 8 (2–3), 109–114 (1999).

Glover, G. H. et al. Function biomedical informatics research network recommendations for prospective multicenter functional MRI studies. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 36 (1), 39–54 (2012).

Lutkenhoff, E. S. et al. Optimized brain extraction for pathological brains (optiBET). PLoS One. 9 (12), e115551 (2014).

Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23 (Suppl 1), S208–S219 (2004).

Woolrich, M. W. et al. Multilevel linear modelling for FMRI group analysis using bayesian inference. Neuroimage 21 (4), 1732–1747 (2004).

Jenkinson, M. et al. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage 17 (2), 825–841 (2002).

Team, R. RStudio: Integrated Development for R (RStudio, PBC, 2020).

Ovans, Z. et al. Cognitive control States influence real-time sentence processing as reflected in the P600 ERP. Cognition Neurosci. 37 (8), 939–947 (2022). Language.

Fedorenko, E. et al. New method for fMRI investigations of language: defining rois functionally in individual subjects. J. Neurophysiol. 104 (2), 1177–1194 (2010).

Gates, K. M. & Molenaar, P. C. Group search algorithm recovers effective connectivity maps for individuals in homogeneous and heterogeneous samples. Neuroimage 63 (1), 310–319 (2012).

Beltz, A. M. & Gates, K. M. Network mapping with GIMME. Multivar. Behav. Res. 52 (6), 789–804 (2017).

Cheng, X., Schafer, G. & Akyurek, E. G. Name agreement in picture naming: an ERP study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 76 (3), 130–141 (2010).

Righi, G. et al. Neural systems underlying lexical competition: an eye tracking and fMRI study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22 (2), 213–224 (2010).

Wen, J. et al. Evaluating the roles of left middle frontal gyrus in word production using electrocorticography. Neurocase 23 (5–6), 263–269 (2017).

Fujii, M. et al. Intraoperative subcortical mapping of a language-associated deep frontal tract connecting the superior frontal gyrus to broca’s area in the dominant hemisphere of patients with glioma. J. Neurosurg. JNS. 122 (6), 1390–1396 (2015).

Pinet, S. & Nozari, N. Different electrophysiological signatures of Similarity-induced and Stroop-like interference in Language production. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 35 (8), 1329–1349 (2023).

Schmidt, J. R. & De Houwer, J. Now you see it, now you don’t: controlling for contingencies and stimulus repetitions eliminates the Gratton effect. Acta Psychol. (Amst). 138 (1), 176–186 (2011).

Duffy, K. A. et al. Detecting Task-Dependent functional connectivity in group iterative multiple model Estimation with Person-Specific hemodynamic response functions. Brain Connect. 11 (6), 418–429 (2021).

Rodd, J. M., Davis, M. H. & Johnsrude, I. S. The neural mechanisms of speech comprehension: fMRI studies of semantic ambiguity. Cereb. Cortex. 15 (8), 1261–1269 (2005).

Berman, M. G. et al. Evaluating functional localizers: the case of the FFA. Neuroimage 50 (1), 56–71 (2010).

Green, D. W. & Abutalebi, J. Language control in bilinguals: the adaptive control hypothesis. J. Cogn. Psychol. (Hove). 25 (5), 515–530 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [32200845], the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macao S.A.R [FDCT, 0153/2022/A], and Multi-Year Research Grant [MYRG2022-00148-ICI] from the University of Macau to Haoyun Zhang. CTI was supported by the University of Macau (File no: SRG2023-000040-ICI). We thank Yumeng Xiao, and other members from the Language Aging and Bilingualism Lab for their help in data collection. We thank the staff at the Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences (CCBS) at the University of Macau, where the study was conducted, for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. designed the experiment, conducted the study, wrote the initial draft, and prepared all figures. K.K., J.Z., and H.Y. helped with data collection. C.T.I. revised the draft. H.Z. supervised the project, designed the experiment, revised the draft, and provided funding for this project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the beginning of the study.

Institutional review board

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Macau (protocol code BSERE22-APP001-ICI, approved on 17 March 2022).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Kang, K., Zhong, J. et al. Cognitive control states and traits modulate lexical competition during word production. Sci Rep 15, 25381 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10039-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10039-5