Abstract

Universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) is recommended for early identification of congenital hearing impairment (CHI). Evidence has shown that much of the impact of this condition can be mitigated through early detection and intervention. We sought to report findings of UNHS in a setting where it is not effectively implemented, describe the risk profile of potentially hearing impaired babies after screening, and determine factors associated with abnormal results. This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study carried out in three reference hospitals in Cameroon, for a period of three months from January to March 2024. We included all neonates born or admitted in any of these three facilities. Critically ill babies were excluded. A portable non-invasive otoacoustic emission (OAE) device was used. This device is exclusively used for screening, not diagnosis. Results were either “pass” or “refer”, indicating that OAEs were either recorded or not detected respectively. A total of 215 babies were screened. Fifty-three out of 215 newborns had abnormal results (24.7%). Maternal age varied from 13 to 41 years, with a mean of 27.6 years. Among newborns with abnormal OAE results, maternal risk factors found were maternal alcoholism (23; 43.4%), family history of hearing loss (9; 17%), and infections (3; 5.7%). Neonatal risk factors were gentamicin administration (33; 62.3%), acute foetal distress/ neonatal asphyxia (19; 35.8%), and meningitis (7; 13.2%). Statistically significant risk factors identified on multivariate analysis included maternal alcoholism (adjusted OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.8, p = 0.002), the use of gentamicin (adjusted OR 5, 95% CI 2.3–10.8, p < 0.001), neonatal asphyxia (adjusted OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.2–6.4, p < 0.001), and meningitis (adjusted OR 6.3, 95% CI 1.1–35.7, p = 0.04). Without UNHS, many children with CHI are probably missed at the time when they would benefit most from treatment. Despite the cost-effectiveness of screening methods, and the availability of hearing specialists in some hospitals in Cameroon, UNHS is still not implemented. Risk factors for CHI are common among babies born in Cameroon. Diagnosis and management of CHI should be preceded by preventive measures, which include good perinatal care and satisfactory control of risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) is considered the gold standard towards early identification of congenital hearing impairment (CHI), and has been widely adopted in most high income countries. Evidence has shown that much of the impact of CHI can be mitigated through early detection and interventions. These interventions include proper characterization of the defect, treatment, rehabilitation and prevention, leading to improved developmental outcomes later in childhood1. In most high income countries, neonatal hearing screening programs are available to detect and manage CHI. These programs aim to screen all newborns within one month of birth1. They also provide a wide variety of social services, accessibility enhancement and rehabilitation programs.

According to a World Health Organization (WHO) 2024 report2, about 40 million people live with HI in the African region, but the figure could rise to 54 million by 2030 if urgent measures are not taken to address the problem. Without urgent interventions, widespread hearing loss, which disproportionately affects poor and vulnerable populations, will continue to escalate, amplifying existing inequalities in health services access across Africa. For children, the far-reaching consequences of hearing loss include delays in language development, raising the risk of poor educational outcomes and limited future career prospects2. Despite this, UNHS programs are scarce across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). There is evidence to suggest that the lack of UNHS programs in Africa is detrimental to hearing-impaired children3,4. While the available technology for UNHS is appropriate and affordable for employment in income countries (LMICs), the advantages and benefits of early detection and early intervention services for infants with hearing impairment (HI) are not always available and easily reachable3,5. In Cameroon specifically, very few facilities effectively conduct systematic screening of newborns. Furthermore, some studies report scarcity and overt unevenness in distribution of specialists, equipment and solutions to CHI5. Reporting findings and outcome of UNHS in Cameroon could contribute to raising awareness on the scope of CHI, and the relevance and urgency of implementing comprehensive programs. The objectives of this study were to report findings of UNHS, describe the risk profile of potentially hearing impaired babies after screening, and determine factors associated with abnormal results.

Methods

Study design and procedure

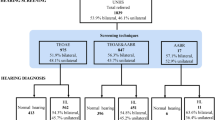

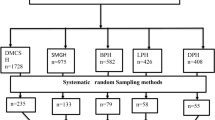

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study carried out in three reference hospitals in Cameroon; Yaoundé Central Hospital, Yaoundé Gynaecology Obstetric and Paediatric Hospital, and CB Foundation, for a period of three months from January 2024 to March 2024. These hospitals are referral centres that provide the highest level of care in neonatology, paediatrics, and obstetrics/gynaecology in the country. They have specialists, residents, specialized nurses, as well as good equipment for optimal care, and hence receive women and infants from all over the country. We included all neonates born at any of these three institutions, either awaiting discharge or admitted for further care, after obtaining informed consent from their care provider. We excluded critically ill neonates, defined as newborn babies with an immediately life-threatening illness or injury, due to their need for uninterrupted care and monitoring. A consecutive sampling was used to recruit all eligible neonates born in any of these three hospitals during the study period. The investigator visited the maternity and neonatology units of these hospitals on a daily basis to identify potential participants. The parent was informed about the objectives of the study, the benefits of the test, and its non-harmful nature. Verbal consent was approved due to the low risk of the procedure, and the cultural context of the study, with a few mothers unable to read and write. Following verbal consent, a portable non-invasive otoacoustic emission (OAE) testing device of brand Grason-Stadler Corti® (Eden Prairie, Minnesota) acquired for the purpose of the study was used for screening. The device tests both distortion product OAEs and transient evoked OAEs, assessing up to 12 frequencies from 1.5 to 12 kHz. Hearing screening was carried out in a quiet and calm testing room with no background noise. The test was performed in a calm newborn, either awake in the arms of their caregiver, or asleep. The OAE device was properly calibrated and the probe snugly placed in each ear canal. Results were either “pass”, indicating that OAEs were successfully measured in both ears, suggesting normal cochlear function, or “refer”, indicating that OAEs were not detected in one or both ears, suggesting risk of hearing loss. Parents of babies whose results were positive for suspected HI were advised on the steps to follow. An appointment was made to confirm the result using auditory-evoked brainstem response. We did not consider the confirmatory results, as this would have required a long follow up period not convenient for this study. They were given information on the different management steps, options, and expectations in case CHI was confirmed, as well as their availability in Cameroon.

Statistics

Data collected included maternal socio-demographic and clinical characteristics (age, educational level, occupation, alcoholism, smoking, and family history of HI or genetic syndrome), antenatal history (antenatal toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes and other infections (TORCH), and antenatal medications), perinatal history (mode of delivery, instrumental delivery, notion of prolonged labour and reason), neonatal demographics (sex, birth weight, and gestational age at birth), neonatal risk factors (acute foetal distress/neonatal asphyxia, neonatal jaundice, kernicterus, severe malaria, meningitis, rhesus incompatibility, genetic syndrome, and ototoxic drug administration). OAE results were recorded as either pass or refer. Results were presented as means for quantitative variables, and percentages for qualitative variables. Data were analysed using SPSS® version 25 (College Station, Texas). Statistical significance was set at p value < 0.05 for all comparisons.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Buea, Cameroon. Administrative authorizations were sought from the administration of the concerned hospitals. Confidentiality and privacy were ensured during data collection by using assigned codes. Colleagues practising in the referral hospitals where data were collected were included as authors, as they significantly contributed to this study. All other relevant guidelines and regulations for ethical and suitable cross-sectional studies were followed.

Results

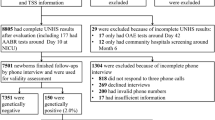

A total of 232 potentially eligible neonates were approached, among whom 215 were screened. Fifty-three out of 215 newborns had abnormal results, giving a proportion of 24.7%. Of these 53 newborns, 35 (66%) had absent OAEs on one side, while 18 (34%) had absent OAEs on both sides. Maternal age varied from 13 to 41 years, with a mean of 27.6 ± 6.7 years. Demographic characteristics of the study population are represented on Table 1.

The most common maternal risk factors for HI identified were maternal alcoholism (50; 23.3%), family history of hearing loss (24; 11.2%), and TORCH infections (19; 8.8%), while neonatal risk factors included gentamicin administration (71; 33%), acute foetal distress/ neonatal asphyxia (42; 19.5%), and neonatal jaundice (32; 14.9%). Table 2 depicts the HI risk profile of all study participants.

Among newborns with abnormal OAE results, maternal risk factors found were maternal alcoholism (23; 43.4%), family history of HI (9; 17%), and TORCH infections (3; 5.7%), and neonatal risk factors were gentamicin administration (33; 62.3%), prematurity (23; 43.4%), low birth weight (20; 37.7%), acute foetal distress/ neonatal asphyxia (19; 35.8%), neonatal jaundice (10; 18.9%), meningitis (7; 13.2%), and genetic syndrome (4; 7.5%). Statistically significant risk factors identified on multivariate regression analysis included maternal alcoholism (adjusted OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.8, p = 0.002), the use of gentamicin (adjusted OR 5, 95% CI 2.3–10.8, p < 0.001), neonatal asphyxia (adjusted OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.2–6.4, p < 0.001), and meningitis (adjusted OR 6.3, 95% CI 1.1–35.7, p = 0.04). Table 3 shows the association between identified risk factors and suspicion of HI following screening on multivariate regression analysis.

Discussion

Cameroon is a LMIC, partitioned into 10 administrative regions. This study was conducted in the Centre Region, within which the capital city is located. The referral hospitals concerned comprise specialists intervening in hearing care. Our findings reveal that risk factors for CHI are frequent, with unsuspecting factors such as maternal alcoholism being relatively common. Despite the availability of adequate equipment, and the level of care they provide, UNHS is not implemented in these facilities.

As many as 24.7% of babies required hearing test confirmation due to absence of OAEs. This not only brings out the importance and urgency of systematic screening and implementation of UNHS, but also the identification and control of potential risk factors. The hospitals in which this study was carried out receive women referred for delivery and neonates from semi-urban and rural settings. The reasons for referring women in labour in Cameroon are mainly cephalopelvic disproportion and foetal distress6,7, which are both known risk factors for CHI1,8,9. The absence of optimal equipment and specialist care in most facilities in rural settings could lead to suboptimal pregnancy and neonatal care, potentially exposing more newborns to a higher risk of CHI. Interestingly, alcohol consumption during pregnancy was the most common maternal predisposing factor reported. Maternal alcoholism can result to at least four types of hearing disorders, resulting from prenatal alcohol exposure; delayed maturation of the auditory system, sensorineural hearing loss, intermittent conductive hearing loss secondary to recurrent serous otitis media, and central hearing loss10. This finding is pertinent in a setting where alcohol consumption and drug abuse among youths are steadily rising due to rural exodus, unemployment, social media influence, and subsequent increased psychological distress. A family history of HI was also found in a few women. The absence of genetic testing in Cameroon constitutes a major setback in assessing and pre-empting hereditary forms of CHI.

The most significant neonatal risk factor associated with abnormal results was ototoxicity, notably the use of gentamicin. Gentamicin is commonly used in most hospitals in Cameroon, together with two other antibiotics, as empirical antibiotic protocol for the treatment of neonatal bacterial sepsis. The role of gentamicin in CHI is controversial. There is evidence that aminoglycosides can cause permanent damage to inner ear hair cells, resulting in hearing loss (cochleotoxicity) and/or vestibular disturbances such as disequilibrium (vestibulotoxicity). Furthermore, gentamicin can cause damage to the outer hair cells of the cochlea, resulting in permanent sensorineural hearing loss, as well as vestibular injury, producing permanent loss of balance11,12,13. However, other authors indicated that gentamicin administration within the observed doses and durations of exposure is not associated with hearing screen failure14,15. Considering that the medication was administered properly, our presumption is that the potential HI in these newborns is a consequence of neonatal sepsis, which was the reason why the drug was administered. Bacterial sepsis in newborns has been described to be associated with hydrocephalus, mild developmental delay, and deafness, notably gram-negative sepsis16, the most common causative agent in Cameroon17. This condition is still common among newborns in Cameroon18, and further bolsters the need for improvement of perinatal care for pregnant women in all parts of the country, given that these infections are generally contracted in the perinatal period. Further studies are needed to confirm whether our findings are due the drug itself or the underlying illness. Remarkably, most of the other predisposing factors identified among babies with abnormal results, though not statistically significant, were linked to inappropriate pregnancy and perinatal care; these included prematurity, low birth weight, acute foetal distress, and neonatal asphyxia. Our results portray the frequency of risk factors for CHI in our setting, pertaining to the fragile nature of the health care system and the challenges in access to proper care in all parts of the country. While awaiting the effective implementation of UNHS, clinicians should intentionally request screening for exposed newborns, especially those exposed to maternal alcoholism, neonatal sepsis, neonatal asphyxia, and meningitis. Scholarly associations should not relent in advocacy efforts for policy-makers and health facility administrators to effectively implement UNHS, at least in hospitals that can provide specialist care and follow-up. CHI prevention should begin with adequate and optimal neonatal care, which would control many causes of CHI in our setting. Training of more specialized personnel, provision, and equitable distribution of resources could significantly improve the overall quality of care. Finally, alcoholism urgently needs to be controlled. This would require an effective multifaceted national strategy to control all potential factors contributing to the problem.

Limitations of this study include the fact that it was conducted in only three facilities. Findings related to risk factors are therefore not generalizable. In addition, the use of OAE, which is only a screening tool, and not a diagnostic test constitutes another limitation. Finally, confirmatory auditory-evoked brainstem response results were not included.

Conclusion

Without UNHS, many children with CHI are probably missed at the time when they would benefit most from treatment. Despite the cost-effectiveness of screening methods, and the availability of hearing specialists in some hospitals in Cameroon, UNHS is still not implemented. Risk factors for CHI are common among babies born in Cameroon. Diagnosis and management of CHI should be preceded by preventive measures, which include good perinatal care and satisfactory control of risk factors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CHI:

-

Congenital hearing impairment

- HI:

-

Hearing impairment

- LMIC:

-

Low-middle income country

- OAE:

-

Otoacoustic emission

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TORCH:

-

Toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes and other infections

- UNHS:

-

Universal newborn hearing screening

- WHO:

-

World health organisation

References

Korver, A. M. et al. Congenital hearing loss. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer. 3, 16094 (2017).

WHO Regional Office for Africa: WHO report on Burden of hearing loss in Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/news/burden-hearing-loss-africa-could-rise-54-million-2030-who-report (2024). Accessed 8 Dec 2024.

Khoza-Shangase, K. & Harbinson, S. Evaluation of universal newborn hearing screening in South African primary care. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 7, 769 (2015).

Hyde, M. L. Newborn hearing screening programs: Overview. J. Otolaryngol. 34, 70–78 (2005).

Choffor-Nchinda, E. et al. Approach and solutions to congenital hearing impairment in Cameroon: Perspective of hearing professionals. Trop. Med. Health 50, 36 (2022).

Mforteh, A. A. et al. Appropriateness of indications of caesarean sections in a district setting of cameroon. Mathews J. Gynecol. Obstet. 5, 1–33 (2020).

Tanyi, T. J., Atashili, J., Fon, P. N., Robert, T. & Paul, K. N. Caesarean delivery in the Limbé and the Buea regional hospitals, Cameroon: Frequency, indications and outcomes. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 24, 227 (2016).

Congenital Hearing Loss—An overview. ScienceDirect Topics. 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/congenital-hearing-loss. Accessed 23 Dec 2024.

Alhazmi, W. Risk factors associated with hearing impairment in infants and children: A systematic review. Cureus 15, e40464 (2023).

Church, M. W. & Abel, E. L. Fetal alcohol syndrome: Hearing, speech, language, and vestibular disorders. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 25, 85–97 (1998).

Dobie, R. A., Black, F. O., Pezsnecker, S. C. & Stallings, V. L. Hearing loss in patients with vestibulotoxic reactions to gentamicin therapy. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 132, 253–257 (2006).

Blunston, M. A., Yonovitz, A., Woodahl, E. L. & Smolensky, M. H. Gentamicin-induced ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity vary with circadian time of treatment and entail separate mechanisms. Chronobiol. Int. 32, 1223–1232 (2015).

Ahmed, R. M., Hannigan, I. P., MacDougall, H. G., Chan, R. C. & Halmagyi, G. M. Gentamicin ototoxicity: A 23-year selected case series of 103 patients. Med. J. Aust. 196, 701–706 (2012).

Ekmen, S. & Doğan, E. Evaluation of gentamicin ototoxicity in newborn infants: A retrospective observational study. J. Pediatr. Perspect. 9, 13137–13144 (2021).

Puia-Dumitrescu, M. et al. Evaluation of gentamicin exposure in the neonatal intensive care unit and hearing function at discharge. J. Pediatr. 203, 131–136 (2018).

Gans, H. A. & Darmstadt, G. L. Bacterial sepsis in the neonate. In Fetal Neonatal Brain Inj (eds Stevenson, D. K. et al.) 456–480 (University Press, 2017).

Chiabi, A. et al. The clinical and bacteriogical spectrum of neonatal sepsis in a tertiary hospital in Yaounde, Cameroon. Iran J. Pediatr. 21, 441–448 (2011).

Noukeu, N. D. et al. Determinants of neonatal mortality in a neonatology unit in a referral hospital in Douala, Cameroon. Health Sci. Dis. 23, 99–104 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the parents who voluntarily participated in this study.

Funding

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC-N conceived and designed this study. EC-N, NM, AM, and AB participated in data acquisition. EC-N and AM analysed data. EC-N drafted the manuscript, RCMB and ARNN provided critical insight. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Buea, Cameroon. Verbal consent to participate in the study was obtained from parents after they were informed about the objectives of the study, the benefits, and non-harmful nature of otoacoustic emission testing.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choffor-Nchinda, E., Monono, N., Mawota, A. et al. Outcome of universal newborn hearing screening conducted in three referral hospitals in Cameroon. Sci Rep 15, 24394 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10150-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10150-7