Abstract

Previous research has demonstrated an inverse relationship between optimal cardiovascular health (CVH) and the prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA). The American Heart Association has evolved its Life Simple 7 (LS7) metric into Life Essential 8 (LE8), which exhibits enhanced sensitivity to inter-individual variations and places increased emphasis on social determinants of health and mental well-being. The primary objective of this study was to examine the potential relationship between the CVH (LE8) score and the health status of patients with OA. Additionally, this study aimed to investigate the possible association between the CVH (LE8) score and other forms of arthritis, as well as to draw comparisons among different arthritis types. This observational study utilized data from the NHANES, conducted from 2005 to 2018. To examine the association between the CVH LE8 score and various arthritis types, multiple statistical approaches were employed. These included weighted multivariable logistic regression analysis, subgroup analysis, and restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis. The study included 29,324 participants. Results indicated an inverse relationship between CVH (LE8 score) tertiles and the likelihood of developing OA (tertile 1, 10.14%; tertile 2, 7.47%; tertile 3, 4.61%; p < 0.001) and Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (tertile 1, 9.60%; tertile 2, 6.67%; tertile 3, 2.86%; p < 0.001). No statistically significant difference was observed for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) across the three CVH categories (p = 0.125). In the fully adjusted model 3, logistic regression analysis revealed that a higher CVH (LE8) score was associated with a lower prevalence of OA (OR = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.35–0.54, p < 0.001) and RA (OR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.35–0.50, p < 0.001). Furthermore, diet, exercise, nicotine exposure, body mass index, and blood pressure were significantly associated with OA (p < 0.05). RCS analyses demonstrated a linear relationship between the CVH (LE8) score and OA, RA, and PsA (p-overall < 0.001, p-nonlinear > 0.05). The cardiovascular health (Life Essential 8) score demonstrated a negative linear association with the prevalence of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis among US adults. These findings offer valuable insights for developing early intervention strategies targeting populations susceptible to arthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease characterized by cartilage degeneration, bone proliferation, osteophyte formation, joint space narrowing, and degenerative inflammation1. It has emerged as the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting over 500 million individuals2,3. Numerous studies have demonstrated that various cardiovascular disease-related risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking, sleep disturbances, inflammation, and physical inactivity, are closely associated with the progression and prognosis of of osteoarthritis (OA)4,5,6,7,8,9. While the precise etiology of OA remains elusive, there is growing consensus that environmental factors, particularly health behaviors and diet, play crucial roles in the development of this disease10,11.

The concept of cardiovascular health (CVH) was introduced by the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2010, encompassing both lifestyle factors and biological metrics12. The original algorithm for evaluating CVH was the Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) score12. Recently, the AHA proposed a new scoring system, Life’s Essential 8 (LE8), which includes diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, sleep health, body mass index, blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure as a comprehensive tool to assess CVH13. Compared to the original CVH metrics (LS7), the new scoring system and the inclusion of sleep factors enable Life Essential 8 (LE8) to provide a more comprehensive and detailed assessment of CVH status at both population and individual levels13,14. These factors play a pivotal role in maintaining overall CVH and are closely associated with OA. Epidemiological studies have shown that conventional risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and low physical activity, are associated with the development and progression of OA15. Furthermore, research has indicated that shorter duration and lower quality of sleep at night are associated with an elevated risk of developing knee OA16. However, a recent study suggests an association between higher LE8 scores and a decreased prevalence of disabilities in physical functioning and functional limitations among OA patients17.

Utilizing the latest data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), our primary objective was to investigate the potential relationship between CVH (LE8) scores and the health status of individuals with OA. The secondary aim of the study was to examine potential associations between CVH (LE8) scores and other types of arthritis, as well as to draw comparisons between different types of arthritis.

Methods

Overview of NHANES and ethics

NHANES, a recurring cross-sectional health survey program, collects data from a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized United States citizens to assess nutrition and health status18,19. The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved the NHANES, and all participants provided written informed consent. In addition, we confirmed that all data were collected and analyzed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and cited previously published high-quality literature in each of the data collections as additional notes.

Study population

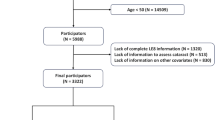

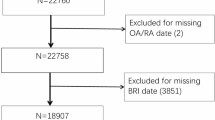

This study utilized data from the NHANES spanning 2005 to 2018. Participants were included if they had complete data for LE8 components and various arthritis types. To ensure result validity and reliability, exclusion criteria were applied as follows: (1) individuals with incomplete data pertaining to arthritis and CVH (LE8) scores were excluded to reduce potential biases and enhance analysis robustness; (2) pregnant and lactating women were also excluded due to potential metabolic profile alterations that could impact the analysis.

Assessment of arthritis

Arthritis status was determined through responses to a questionnaire on medical conditions. In alignment with previous studies20,21 participants were asked whether a doctor or health professional had ever diagnosed them with arthritis, and if so, which type. Individuals who confirmed a professional diagnosis of arthritis were classified as having “arthritis”. Those who self-reported “osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis” were categorized as “OA”, “rheumatoid arthritis” as “Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)”, and “psoriatic arthritis” as “psoriatic arthritis (PsA)”. A previous study demonstrated 81% concordance between self-reported and clinically confirmed diagnoses22. While self-reporting and selection biases remain potential limitations, rigorous standardized procedures were implemented to ensure reliable data quality.

Quantification of CVH: life’s essential 8 score

The new CVH definition comprises eight metrics, categorized into two domains for ease of reference in clinical or research settings: health behaviors (diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep) and health factors (body mass index, blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure). The AHA determined that an ordinal point scoring system for each metric (ranging from 0 to 100 points) was the most effective method for quantifying the metrics and overall CVH. The total CVH score was calculated by averaging the scores from the 8 measures. Following AHA recommendations, we classified the overall CVH into three levels (high: LE8 ≥ 80, moderate: 50 ≤ LE8 < 80, low: LE8 < 50)23. Previous research has validated the LE8 triple classification method24. To further investigate the relationship between LE8 subscales and arthritis, we applied the same definition and cut-off points to measure and classify health behaviors and health factors in this study. In our analysis, LE8 served as the exposure variable.

Diet

Dietary information in this study was collected using a self-reported food frequency questionnaire. Diet quality was assessed using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 201525. The HEI-2015 evaluated diet metrics across five percentile ranges (1st-24th, 25th-49th, 50th-74th, 75th-94th, and ≥ 95th), corresponding to scores of 0, 25, 50, 80, and 100 points, respectively. While self-report and selection biases are potential limitations, stringent standardized procedures were implemented to ensure reliable data quality.

Physical activity

Physical activity assessment utilized the NHANES PAQ-K questionnaire, which quantified weekly moderate or vigorous exercise duration13,23. The physical activity time was categorized into intervals of 0, 1–29, 30–59, 60–89, 90–119, 120–149, and 150 min per week, corresponding to point values of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 90, and 100, respectively.

Nicotine exposure

The NHANES SMQ134 questionnaire, which assessed self-reported use of cigarettes or inhaled nicotine, was utilized to quantify nicotine exposure26. Five nicotine exposure categories were established: current smoker, former smoker (quit < 1 year) or current user of inhaled nicotine delivery systems, former smoker (quit 1 to < 5 years), former smoker (quit ≥ 5 years), and never smoker, corresponding to 0, 25, 50, 80, and 100 points, respectively. Adults residing in homes with an active indoor smoker had 20 points deducted from their score.

Sleep health

In alignment with previous research13,27 sleep health was assessed using a questionnaire to collect self-reported average hours of sleep per night. Sleep duration was categorized as follows: <4, 4 to < 5, 5 to < 6 or ≥ 10, 6 to < 7, 9 to < 10, and 7 to < 9 h, corresponding to 0, 20, 40, 70, 90, and 100 points, respectively. Trained interviewers administered the questionnaire at participants’ homes using a computer-assisted personal interview system to ensure data integrity, consistency, and analytical utility.

Body mass index (BMI)

In accordance with previous research methodologies, BMI was calculated using weight and height measurements obtained by trained study personnel. Participants were categorized into four groups based on their BMI: 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 (normal weight), 25.0–29.9 (overweight), 30.0–34.9 (obese grade 1), and ≥ 35.0 (obese grade 2 and 3)28,29,30.

Blood lipids

A study by Jiahong Sun, et al. demonstrated that non-HDL cholesterol was measured and calculated from blood samples to evaluate blood lipid profiles. Non-HDL levels were categorized as ≥ 220, 190–219, 160–189, 130–159, and < 130 mg/dL, corresponding to scores of 0, 20, 40, 60, and 100, respectively13,27.

Blood glucose

In accordance with previous research13,27 blood samples were utilized to evaluate blood glucose levels by measuring HbA1c (%) and fasting blood glucose (FBG, mg/dL). Blood glucose levels were categorized as follows: diabetes with HbA1c ≥ 10.0%, diabetes with HbA1c of 9.0-9.9%, diabetes with HbA1c of 8.0-8.9%, diabetes with HbA1c of 7.0-7.9%, diabetes with HbA1c < 7.0%, no diabetes and fasting blood glucose (FBG) of 100–125 mg/dL or HbA1c of 5.7–6.4%, and no history of diabetes and FBG < 100 mg/dL or HbA1c < 5.7%. These categories corresponded to 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, and 100 points, respectively.

Blood pressure

In accordance with previous studies13,27 blood pressure assessment encompassed both systolic and diastolic measurements. The scoring system for blood pressure was as follows: systolic pressure of 160 mmHg or diastolic pressure of 100 mmHg scored 0 points; 140–159 mmHg systolic or 90–99 mmHg diastolic scored 25 points; 130–139 mmHg systolic or 80–89 mmHg diastolic scored 50 points; 120–129/80 mmHg scored 75 points; and 120/80 mmHg scored 100 points. For individuals undergoing blood pressure treatment, a deduction of twenty points was applied.

Covariates

Our study incorporated covariates that potentially influence the association between LE8 and arthritis. These included gender (Male/Female), age (Years), race (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Others), education level (Less than high school, High school, More than high school), diabetes status (Yes/No), cancer history (Yes/No), Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII), uric acid levels, and poverty ratio. The poverty ratio was calculated as the ratio of monthly household income to poverty thresholds specified by the Department of Health and Human Services. Detailed measurement procedures for all variables are publicly accessible at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses adhered to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, utilizing appropriate NHANES sampling weights and accounting for the complex multistage cluster survey design. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard errors (SE), while categorical characteristics were reported as proportions. To evaluate differences between participants stratified by LE8 tertiles, a weighted Student’s t-test (for continuous variables) or a weighted chi-squared test (for categorical variables) was employed.

Associations between the CVH score and outcomes were analyzed using multivariable-adjusted regression models. To improve clinical interpretability, the CVH score was scaled in 10-point increments (e.g., a 10-unit increase from 0 to 100), consistent with its theoretical range. This approach allowed us to estimate effect sizes per decade of the score while retaining its continuous nature in statistical models. Model 1 remained unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for sex, age, and race. Model 3 incorporated adjustments for sex, age, race, education level, poverty-income ratio (PIR), diabetes, cancer, SII, and uric acid.

Subgroup analyses investigating the associations between CVH (LE8) score and osteoarthritis (OA) were performed using stratified factors including Gender (Male/Female), Age (< 60/≥ 60 years), Race (Non-Hispanic White/Non-Hispanic Black/Mexican American/Other Hispanic/Others), Education level (Less than high school/High school/More than high school), and Diabetes (Yes/No). These stratified factors were also considered as pre-specified potential effect modifiers. Missing values were imputed using the median for continuous variables or mode for categorical variables of existing cases. The strength of associations in multivariate models was estimated using odds ratios (OR) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Lastly, the association between CVH (LE8) score and different types of arthritis was examined using restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.4.3 (solutions, Inc., Boston, MA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Following the application of exclusion criteria, 37,622 participants were excluded due to insufficient CVH, 202 due to pregnancy and breastfeeding, and 55 due to missing arthritis data. Consequently, the final study population comprised 29,324 participants. Figure 1 depicts the participant selection process.

Baseline characteristics of participants

The study included 29,324 individuals. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the study population. Among the participants, 20.3% had low CVH (LE8 < 50), 64.79% had moderate CVH (50 ≤ LE8 < 80), and 14.91% had high CVH (LE8 ≥ 80). Statistically significant differences were observed among the three CVH tertiles in age, gender, race, education level, ratio of income to PIR, diabetes, cancer, and uric acid levels (all p < 0.001). Participants with high CVH, compared to those with low CVH, were more likely to be younger, female, Non-Hispanic White, have lower uric acid levels, higher education levels, and higher ratios of family income to poverty (all p < 0.001). Individuals with diabetes, cancer, osteoarthritis (OA), or RA were less likely to have higher CVH scores (all p < 0.001). Notably, there was no statistically significant difference in PsA prevalence among the three CVH categories (p = 0.125). To visually compare the mean expression of the 9 CVH scores between OA and non-OA participants, radar charts were employed (Fig. 2). The findings indicate that OA individuals exhibited higher mean values solely for the diet score compared to non-OA participants.

The association between CVH (LE8) score and different types of arthritis

Table 2(a) illustrates the association between CVH (LE8) score and OA. Our findings revealed that a higher CVH (LE8) score was associated with a lower prevalence of OA. This association was statistically significant across all models: Model 1 (OR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97–0.98, p < 0.0001), Model 2 (OR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.98–0.99, p < 0.0001), and Model 3 (OR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.98–0.99, p < 0.0001). These results indicate that each unit increase in CVH (LE8) score corresponded to a 2% decrease in the prevalence of OA. For sensitivity analysis, we converted the CVH (LE8) score from a continuous to a categorical variable (tertiles). Compared to the lowest CVH (LE8) score tertile, participants in the highest tertile (OR = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.35–0.54, p < 0.001) and middle tertile (OR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.67–0.84, p < 0.001) exhibited a 56% and 25% lower prevalence of OA, respectively.

Table2(b) demonstrates the association between CVH (LE8) score and RA. Consistent with the findings in Table 2(a), higher CVH (LE8) scores were associated with lower RA prevalence. Relative to the lowest CVH (LE8) score tertile, participants in the highest tertile (OR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.35–0.50, p < 0.001) and middle tertile (OR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.62–0.76, p < 0.001) showed a 58% and 32% lower prevalence of RA, respectively.

Table2(c) presents the association between CVH (LE8) score and PsA. No statistically significant difference was observed in PsA prevalence between participants in the highest CVH (LE8) tertile (OR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.19–1.06, p = 0.083) and the lowest tertile. However, compared to the lowest CVH (LE8) score tertile, participants in the middle tertile (OR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.22–0.65, p < 0.001) demonstrated a 63% lower prevalence of PsA.

The association between components of the CVH (LE8) score and OA

Table 3 illustrates the association between components of the CVH LE8 score and osteoarthritis (OA). In model 3, adjusted for partial covariates, several components demonstrated statistically significant associations with the prevalence of OA development. The DASH diet score (OR = 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00,1.02, p = 0.0240), physical activity score (OR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97,0.99, p = 0.0005), tobacco/nicotine exposure score (OR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.95–0.97, p < 0.0001), body mass index score (OR = 0.91; 95% CI, 0.90,0.92, p < 0.0001), and blood pressure score (OR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97,1.00, p = 0.0342) all showed significant relationships. However, sleep health scores did not exhibit statistically significant differences in relation to OA across Models 1, 2, and 3 (p > 0.05).

Subgroup analysis

The findings from subgroup analyses are presented in Table 4. Stratification by sex, age, race, education level, and diabetes revealed a significant interaction between age and race in the relationship between CVH (Life Essential 8 [LE8]) scores and osteoarthritis (OA) (interaction p < 0.05). However, gender, education level, and diabetes did not significantly influence the association between CVH (LE8) score and OA (all p for interaction > 0.05).

Restricted cubic splines (RCS) analysis examining the association between CVH (LE8) score and three distinct types of arthritis

In Fig. 3, we utilized restricted cubic spline analysis to flexibly model and visualize the associations between CVH LE8 score and three different types of arthritis. After adjusting for all covariates in the master analytical model, a linear correlation was observed between CVH (LE8) score and osteoarthritis (OA) (P-overall < 0.001, P-nonlinear > 0.05). Similarly, CVH (LE8) score exhibited linear correlations with RA and PsA (P-overall < 0.05, P-nonlinear > 0.05).

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative prospective cohort study of US adults, we observed a linear negative correlation between the CVH LE8 score and the prevalence of all types of arthritis, including osteoarthritis (OA), RA, and PsA. Subgroup analysis indicated that the negative association between CVH (LE8) score and OA was more pronounced among Non-Hispanic and younger participants. These findings suggest a novel approach for early screening and treatment of arthritis.

Our study revealed that among the individual components of the CVH (LE8) score, lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity level, and nicotine exposure, as well as metabolic indicators like BMI and blood pressure, are closely associated with arthritis. These factors may influence arthritis development and progression through various mechanisms. Consistent with previous research, Sajedeh Jandari et al.31 found that adopting a diet with higher HEI scores significantly reduces the likelihood of developing RA. Similarly, a recent US cross-sectional study reported significantly different HEI scores between individuals with RA (51.41 ± 0.37) and healthy subjects (53.50 ± 0.28)32. This phenomenon may be related to the reduction of the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) in RA31,33,34. Evidence clearly demonstrates that moderate physical activity has a protective effect on arthritis patients35,36 possibly due to improvements through the downregulation of TRAIL37. However, excessive exercise can cause progressive damage, inhibiting matrix synthesis and thereby increasing arthritis risk38,39. A meta-analysis revealed that smokers are more likely to develop RA than non-smokers40which may be related to the formation of citrullination of antigens and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) in RA41,42. Conversely, meta-analyses have indicated a negative association between smoking and osteoarthritis43,44. Obesity is a crucial risk factor for OA onset and progression45,46,47 with previous studies showing a positive association between body roundness index (BRI) and OA risk48. The mechanisms by which obesity leads to OA include excessive mechanical loading49 and activation of inflammatory pathways and related factors, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and NF-κB, resulting in irreversible matrix degradation and contributing to apoptosis50,51,52. An observational and Mendelian randomization analysis53 showed no causal relationship between OA and hypertension, but a higher risk of hypertension in the male subgroup of OA patients, aligning with prior literature54,55,56,57. Recent Mendelian randomization studies have indicated a causal relationship between androgen and osteoarthritis occurrence58suggesting that androgen signaling may partially explain the association between osteoarthritis and hypertension. Our study found no independent association between sleep health and Arthritis (AR). However, contrary to our findings, a prospective cohort study demonstrated that healthy sleep patterns significantly reduced RA risk in a dose-response manner59 and a case-control study involving 4176 individuals showed that shift work was associated with a higher RA risk60. These discrepancies may be related to inconsistent sleep subgrouping and insufficient description of sleep characteristics. The CVH (LE8) score, as a comprehensive indicator, demonstrates superior ability in identifying arthritis, supporting its application in arthritis prevention and identification.

Subgroup analyses revealed a trend association between CVH (LE8) scores and OA, with P values for the trend < 0.001 for each subgroup. We identified interactions between CVH (LE8) scores and age, and race (interaction p < 0.05). The odds ratio (OR) of OA was higher in the age < 60 years group compared to the elderly, indicating a closer relationship between CVH (LE8) score and OA in the non-elderly population and emphasizing the importance of early OA prevention. Research has shown that chronological age (CA) is merely a retrospective measure of years lived61 while biological age (BA), calculated based on biochemical indicators of healthy individuals, provides a comprehensive assessment of physiological age62,63. Qiang He et al. demonstrated that adults with accelerated biological aging have an increased risk of OA, particularly among older adults64possibly due to the activation of aging markers such as IL-6 and CRP65,66. This contributes significantly to our understanding of how biological aging is linked to OA development. Additionally, the association between CVH (LE8) scores and OA was stronger in the non-Hispanic group compared to other groups, potentially influenced by factors such as social status, health insurance, and lifestyle67. This study provides new insights for further research on the association between CVH (LE8) scores and OA across different demographic characteristics.

This study examined the relationship between CVH scores, as measured by LE8, and various types of arthritis. The findings revealed a negative correlation between different arthritis types and CVH (LE8) scores, with significant trend tests across all subgroups. This correlation may be attributed to the influence of multiple indicators within the CVH (LE8) scores on arthritis31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. These results suggest that higher CVH (LE8) scores could potentially play a role in arthritis prevention across different types. Furthermore, among the CVH (LE8) indicators, lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, and nicotine exposure, as well as metabolic factors like BMI and blood pressure, demonstrate strong correlations. By focusing on these strongly correlated indicators, multiple aspects can be addressed simultaneously, offering a novel approach to arthritis prevention in future research and interventions.

While some odds ratios (ORs) in our analysis remained close to 1.00 despite strong statistical significance, this finding warrants further interpretation. First, the large sample size of our study provided substantial statistical power to detect even subtle associations, which may explain the strong significance of small ORs. Second, a key factor contributing to this observation is the narrow confidence intervals (CIs) associated with these estimates. The narrow confidence intervals (CIs) observed for these estimates indicate high precision in effect estimation, likely attributable to the study’s large sample size and rigorous data collection. While such precision strengthens the statistical reliability of the observed associations, it does not inherently imply clinical or practical significance. Third, we acknowledge potential multicollinearity among CVH components (e.g., correlations between diet, physical activity, and BMI), which may stabilize OR estimates toward null values but would not diminish their statistical validity. Finally, the clinical importance of these findings lies in the cumulative effect of a 10-point improvement in the CVH score: although individual odds ratios (ORs) may appear modest, focusing on the comprehensive CVH score is more beneficial for the management, prevention, and identification of osteoarthritis. We emphasize that even small ORs for certain factors, when considered in the context of disease burden, may still guide preventive strategies (e.g., screening high-risk populations) due to the potential impact of slight risk increases. Furthermore, we hope future studies will validate the cumulative effects of these small ORs through longitudinal data or experimental designs.

This study presents several strengths. Firstly, it utilizes nationally representative data from the NHANES to investigate the association between CVH (LE8) scores and various arthritis types, enhancing the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the study controls for confounding variables to produce more reliable results. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of causal relationships, necessitating prospective studies with larger sample sizes to elucidate causality. Additionally, the reliance on questionnaires for arthritis diagnosis and health behavior assessment may introduce selection bias.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a clear linear negative correlation between CVH as measured by the LE8 score and osteoarthritis (OA), RA, and PsA within a diverse US population. Consequently, we suggest that the CVH (LE8) score may function as a potential predictor for arthritis, facilitating early detection and prevention strategies. Further research examining the relationship between CVH (LE8) scores and arthritis will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of their association.

Data availability

Availability of dataThe National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dataset is publicly available at the National Center for Health Statistics of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

References

Hanly, R. J. et al. The outcome of cemented acetabular components in total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis defines a proficiency threshold: results of 22,956 cases from the Australian orthopaedic association National joint replacement registry. J. Arthroplast. 34, 1711–1717 (2019).

Quicke, J. G. et al. Osteoarthritis year in review epidemiology & therapy. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 30, 196–206 (2022).

Little, C. B. et al. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis: from mouse models to clinical trials. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 9, 485–497 (2013).

Turkiewicz, A. et al. Cause-specific mortality in osteoarthritis of peripheral joints. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 27, 848–854 (2019).

Zemedikun, D. T. et al. Comorbidity phenotypes and risk of mortality in patients with osteoarthritis in the UK: a latent class analysis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 24, 231 (2022).

Yoshimura, N. et al. Accumulation of metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and impaired glucose tolerance raises the risk of occurrence and progression of knee osteoarthritis: a 3-year follow-up of the ROAD study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 20, 1217–1226 (2012).

Roux, C. H. et al. Impact of smoking on femorotibial and hip osteoarthritis progression: 3-year follow-up data from the KHOALA cohort. Joint Bone Spine. 88, 105077 (2021).

Parmelee, P. A. et al. Sleep disturbance in osteoarthritis: linkages with pain, disability, and depressive symptoms. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 67, 358–365 (2015).

Katz, J. N. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis: a review. JAMA 325, 568–578 (2021).

Palazzo, C. et al. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil Med. 59, 134–138 (2016).

Nguyen, H. D. et al. An increased intake of nutrients, fruits, and green vegetables was negatively related to the risk of arthritis and osteoarthritis development in the aging population. Nutr. Res. 99, 51–65 (2022).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Defining and setting National goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American heart association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 121 (4), 586–613 (2010).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American heart association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American heart association. Circulation 146, e18–43 (2022).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adults and children using the American heart association’s new life’s essential 8 metrics: prevalence estimates from the NHANES, 2013 through 2018. Circulation 146, 822–835 (2022).

Erb, N. et al. Risk assessment for coronary heart disease in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 33, 293–299 (2004).

Zhou, S. et al. Association between nighttime sleep duration and quality with knee osteoarthritis in middle-aged and older chinese: A longitudinal cohort study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 118, 105284 (2024).

Chen, M. et al. Life’s essential 8 and its association with osteoarthritis and disability: a cross-sectional study based on the NHANES 2005–2018 database. Qual. Life Res. Nov. 33 (11), 3141–3153 (2024).

Johnson, C. L. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2011–2014. Vital Health Stat. 2, 1–33 (2014).

Curtin, L. R. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2007–2010. Vital Health Stat. 1–23 (2013).

Yan, Y. et al. The association between triglyceride glucose index and arthritis: a population-based study. Lipids Health Dis. 22, 132 (2023).

Liu, B. et al. The association between systemic immune-inflammation index and rheumatoid arthritis: evidence from NHANES 1999–2018. Arthritis Res. Ther. 25, 34 (2023).

March, L. M. et al. Clinical validation of self-reported osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 6, 87–93 (1998).

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Physical activity and physical fitness: PAQ-K. Accessed February 15 (2022). (2019).

Hao et al. Cardiovascular health and life expectancy among adults in the united States. Circulation 11 (15), 1137–1146 (2023).

Krebs-Smith, S. M. et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118 (9), 1591–1602 (2018).

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Smoking and tobacco use: SMQ. Accessed February 15 (2022). (2015).

Jiahong, S. et al. Association of the American heart association’s new life’s essential 8 with all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality: prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 21, 116 (2023).

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risks; Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmi_dis.htm

World Health Organization. Body mass index-BMI; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi

Kulapong et al. Relationship of body mass index with frailty and all-cause mortality among middle-aged and older adults. BMC Med. 24;20(1):404 (2022).

Sajedeh et al. Dietary inflammatory index and healthy eating index-2015 are associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Public. Health Nutr. 24 (18), 6007–6014 (2021).

Comee, L. et al. Dietary patterns and nutrient intake of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis in the united States. Nutrition 67–68, 110533 (2019).

James, R. H. et al. Perspective: The DII-Lessons Learned, Improvements Made, and Future Directions. Adv Nutr. 1;10(2):185–195 (2019).

Michael, D. et al. Anti-inflammatory dietary inflammatory index scores are associated with healthier scores on other dietary indices. Nutr. Res. 36 (3), 214–219 (2016).

Chenyang et al. Comparative study on the association between types of physical activity, physical activity levels, and the incidence of osteoarthritis in adults: the NHANES 2007–2020. Sci Rep. 4;14(1):20574 (2024).

Rausch Osthoff, A. K. et al. 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77 (9), 1251–1260 (2018).

Yue et al. Moderate mechanical stimulation protects rats against osteoarthritis through the regulation of TRAIL via the NF- κ B/NLRP3 pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 23, 6196398 (2020).

Yue et al. Mechanical stress protects against osteoarthritis via regulation of the AMPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 234 (6), 9156–9167 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Exercise induced meteorin-like protects chondrocytes against inflammation and pyroptosis in osteoarthritis by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/NF-κB and NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 158, 114118 (2023).

Sugiyama, D. et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: A Meta-Analysis of observational studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 70–81 (2010).

Ospelt, C. et al. Carbamylation of vimentin is inducible by smoking and represents an independent autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76 (7), 1176–1183 (2017).

Anderson, R. et al. Smoking and air pollution as pro-inflammatory triggers for the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 18 (7), 1556–1565 (2016).

Hui, M. et al. Does smoking protect against osteoarthritis?? Meta-Analysis of observational studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 1231–1237 (2011).

Kong, L. et al. Association between smoking and risk of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 25, 809–816 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Association between weight-adjusted-waist index and the prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24, 595 (2023).

Zhou, Z. Y. et al. Body mass index and knee osteoarthritis risk: a dose-response meta-analysis. Obes. (Silver Spring). 22, 2180–2185 (2014).

Raud, B. et al. Level of obesity is directly associated with the clinical and functional consequences of knee osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 10, 3601 (2020).

Xudong et al. Association between body roundness index and risk of osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 14;23(1):334 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Pathogenesis and clinical management of obesity-related knee osteoarthritis: impact of mechanical loading. J. Orthop. Translat. 24, 66–75 (2020).

Fang, T. et al. Molecular mechanisms of mechanical load-induced osteoarthritis. Int. Orthop. 45, 1125–1136 (2021).

Zhu, J. et al. Instability and excessive mechanical loading mediate subchondral bone changes to induce osteoarthritis. Ann. Transl Med. 8, 350 (2020).

Sobieh, B. H. et al. Beyond mechanical loading: the metabolic contribution of obesity in osteoarthritis unveils novel therapeutic targets. Heliyon 9, e15700 (2023).

ZhiJie et al. Osteoarthritis and hypertension: observational and Mendelian randomization analyses. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17;26(1):88 (2024).

Bagge, E. et al. Factors associated with radiographic osteoarthritis: results from the population study 70-year-old people in Göteborg. J. Rhuematol. 18 (8), 1218–1222 (1991).

Inoue, R. et al. Medical problems and risk factors of metabolic syndrome among radiographic knee osteoarthritis patients in the Japanese general population. J. Orthop. Sci.. 16 (6), 704–709 (2011).

Lee, B. J. et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional nationwide survey study. J. Rehabil Med. 51 (6), 464–470 (2019).

Sananta, P. et al. Association between diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and knee osteoarthritis in secondary referral hospitals in Indonesia with retrospective cross-sectional study. Annals Med. Surg. 80, 104155 (2022).

Yan, Y. S. et al. Sex steroids and osteoarthritis: a Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 683226 (2021).

Jing et al. Sleep patterns, physical activity, genetic susceptibility, and incident rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 13;22(1):390 (2024).

Hedström, A. K. et al. Relationship between shift work and the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 3, e000475 (2017).

Elliott, M. L. et al. Disparities in the Pace of biological aging among midlife adults of the same chronological age have implications for future frailty risk and policy. Nat. Aging. 1, 295–308 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Associations between biological ageing and the risk of, genetic susceptibility to, and life expectancy associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a secondary analysis of two observational studies. Lancet Healthy Longev. 5, e45–55 (2024).

Moqri, M. et al. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell 186, 3758–3775 (2023).

Qiang et al. The association between accelerated biological aging and the risk of osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public. Health. 11, 12:1451737 (2024).

Freund, A. et al. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 238–246 (2010).

Cesari, M. et al. Inflammatory markers and physical performance in older persons: the InCHIANTI study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 59, 242–248 (2004).

McBurney, C. A. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 14 (5), 463–471 (2012).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81702210) and the Shaanxi Provincial Key R&D Project of China (Grant No. 2022SF-100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributionsPEK: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review & editing; ZY, SLT, WT, KYB: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing- original draft preparationWW, LJ: conceptualization, validation, writing—review & editing; CXX, KH: conceptualization, supervision; writing—review & editing; funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, E., Chen, X., Zhu, Y. et al. The association between the American heart association’s new “Life’s Essential 8” and different types of arthritis: insights from a large population study. Sci Rep 15, 24319 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10201-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10201-z