Abstract

The present paper provides a novel hybrid computational framework that integrates Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) with advanced machine learning techniques to optimize solar thermal collectors employing micro-heat pipe arrays (MHPA) for food dehydration applications. The methodology addresses the fundamental challenge of balancing computational efficiency with prediction accuracy in thermal system design. A validated CFD model generated 935 numerical cases across diverse operational and design parameters, which were used to train and evaluate three machine learning algorithms: linear regression (LR), support vector regression (SVR), and artificial neural networks (ANN). While baseline LR achieved R² = 0.61, optimized SVR and ANN models demonstrated superior performance with R² values of 0.96 and 0.94 respectively. The study identifies a critical transition at 100–300 samples where error rates drop sharply, with optimal performance requiring more than 600 samples. Entropy analysis quantified information transfer between input parameters and thermal efficiency, identifying MHPA thermal conductivity as the most influential parameter (~ 20% mutual information), followed by air inlet temperature (~ 17%) and air velocity (~ 14%). This information-theoretic approach provided clear design priorities by measuring entropy reduction potential of each parameter. Interpretability analysis established optimal operating ranges for key parameters including MHPA equivalent thermal conductivity, power density, glass cover heat transfer coefficient, and air inlet temperature. The hybrid methodology shows promise for efficiently optimizing solar thermal collector designs at lower computational costs than traditional methods to provide valuable insights for solar food drying systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solar thermal technology has been considered as a sustainable and energy-efficient solution for food drying processes across various agricultural and food processing applications, which effectively reduces moisture content in fruits, vegetables, and grains. Solar thermal technological applications for drying food can be broadly categorized as direct and indirect solar heating dryers according to the heat transfer working principles. Direct dryers expose food directly to solar radiation, which are simple to manufacture and design. As direct solar dryers allow the food to be exposed directly to sun and wind, it is popularly used for agricultural goods for its simplicity and cost effectiveness. However, this application has limitation of challenges for hygiene and contamination risks1. Indirect solar dryers separate the drying chamber from direct solar exposure, so the ambient air is initially heated by a solar collector system before being directed into a drying chamber to absorb moisture from food items arranged on rack shelves2,3. Indirect solar drying method offers excellent performance by ensuring high-quality dried products and shortening drying time4.

Solar thermal collectors operate by converting solar radiation into thermal energy through selective absorption surfaces5. The fundamental mechanism involves solar radiation passing through a transparent cover, being absorbed by a dark surface, and transferring heat to a working fluid6,7. Recent advancements in collector design have focused on three main areas: (1) enhanced heat transfer through novel fin geometries and surface treatments8(2) reduced heat losses via improved insulation and selective coatings6(3) integration of thermal storage elements for extended operation9,10.

Hybrid systems, which support photovoltaic and thermal collectors, are becoming increasingly important for solar thermal efficiency11. compares a standard solar water heater with two hybrid systems that integrate thermoelectric generators (TEGs). Using MATLAB finite-difference modeling, researchers found that the hybrid systems improve hot water storage while simultaneously generating electricity through the TEGs, demonstrating clear advantages for energy cogeneration applications.

Many researchers’ work12,13,14,15 reveals that solar thermal collector design is very important factor for improving the overall performance of food drying process. A typical solar thermal collector used in indirect food drying process is depicted in Fig. 1. With the advancement of scientific computing technology, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a pivotal methodology for analyzing and optimizing solar thermal collector performance to help improve the design and efficiency16. studied the temperature variation and air flow velocity under different mass flowrates for sensitivity analysis by using CFD and concluded that CFD is a reliable method to predict solar thermal dryer temperature. Design efforts have been made to improve the absorber plate to increase the solar collector efficiency up to 10%17. CFD has been used to predict the drying uniformity of solar tray design by examining the temperature and velocity profiles18. Similarly, Petros19 developed a commercially available indirect solar dryer through three-dimensional CFD modeling with experiment validation to provide qualitative analysis of temperature and air velocity distribution in the solar chamber. Researchers have also focused on design evaluation and improvement of solar thermal collector20. found that the thermal efficiency of solar dryer could be improved with the adding the exhaust hot air recirculation. Novel design of reflector is added to a conventional solar thermal collector to improve the thermal efficiency as well as life span of the solar thermal dryer21.

Innovative configurations of thermal energy storage applications have been extensively explored to enhance the efficiency and performance of solar energy systems. Recent studies have focused on integrating advanced materials and designs to improve heat transfer and storage capabilities. For instance, the performance evaluation of a solar air heater with staggered/longitudinal finned absorber plates integrated with aluminum sponge porous medium has shown significant improvements in thermal efficiency and heat retention22. Additionally, research on phase change materials (PCMs) storage containers has highlighted various geometries and design considerations that enhance heat transfer rates and storage capacity23. Experimental investigations have also demonstrated the thermal performance benefits of flat and V-corrugated plate solar air heaters with and without PCMs, underscoring the potential of these configurations in thermal energy storage applications24. These advancements contribute to the development of more efficient and sustainable thermal energy storage solutions.

MHPA have been widely utilized in the development of a novel solar thermal collector, which comprises multiple independent micro heat pipes, each featuring an internal design that includes several longitudinal micro fins25,26. This configuration greatly enhances both the heat transfer area and the capillary force. MHPA have the advantage to improve the heat transfer process on the conventional solar thermal collectors. The combined experiment and CFD model to optimize the thermal performance of solar thermal collector with MPHA and evaluated the thermal efficiency under different process conditions and design parameters27.

MHPA has been successfully applied in solar thermal collectors for indirect heating dryers28,29,30. The mechanism and process of a typical MHPA based solar thermal collector is presented in Fig. 2. The solar thermal collector incorporating MHPA technology consists of MHPA heat transfer units with aluminum fins in the condensation region. The collector’s structure includes glass cover, air duct, absorber film, insulation layer, and fins. Within the air duct lies the MHPA’s condensation section, while its evaporation section is attached to the absorber on the opposite side31. Cold ambient air enters the solar thermal collector with a thin film of absorber on top of MHPA. The absorbed solar thermal energy is transferred to the fins (which is usually made of metal material with high thermal conductivity). Cold ambient air passes through the fins and is heated up before exiting the solar thermal collector for drying food.

CFD modeling is physics based mathematical programming code to solve complex equations for solutions, which can be time consuming. The advancement of machine learning is capable to overcome this challenge: The application of machine learning conserves time and reveals significant information patterns within a multi-dimensional data landscape. This method has gained considerable popularity in the fields of thermal science and food engineering 32 33. The unique advantage of machine learning lies in its capability to model physical processes in intricate systems. Machine learning relies on artificial intelligence using data and algorithms while not necessitate detailed mathematical formulations or extensive experimental trials. When sufficient experimental data is accessible, machine learning can forecast the expected output of a system with high level of accuracy.

Performance prediction is crucial as it enables optimization of design parameters before physical prototyping, reducing development costs. In addition, accurate performance models facilitate system integration with other renewable energy technologies. The present study addresses this need by developing a hybrid CFD-ML approach that maintains prediction accuracy while drastically reducing computational requirements.

To better utilize solar thermal collectors for drying food, one needs to consider various aspects of the operational and environmental parameters to maximize the energy efficiency. This present study aims to develop a hybrid model for evaluating and improving the thermal efficiency of a typical solar thermal collector with MHPA for indirect solar dryer by combining CFD and machine learning method. The baseline CFD model will be validated against experiment results in published open literature and a large number of datasets were generated for training machine learning model. The large datasets are capable to provide insights of the impact of different operational and process parameters on the prediction of the thermal efficiency. Then, different machine learning algorithms were applied to build the hybrid model with their accuracy evaluated and optimized.

Methodology

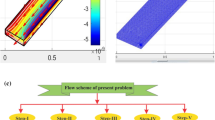

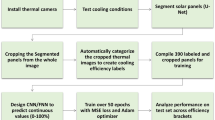

Figure 3 presents the workflow diagram of the hybrid CFD-ML methodology for optimizing solar thermal collector efficiency. The process begins with CFD baseline model development and experimental validation, followed by parameter range definition for input variables and thermal efficiency output. After generating 935 CFD simulation cases using parallel computing, the workflow splits into two parallel paths: statistical analysis (correlation and parameter impact assessment) and machine learning model development (LR, SVR, and ANN with optimization). Both analytical paths converge to provide comprehensive insights for optimized solar thermal collector performance and thermal efficiency prediction.

Since MHPA is a proven widely used technique for solar thermal collector for food drying process, a literature paper is selected to establish a baseline CFD model in the study27. The research paper was chosen for two reasons. Firstly, it has been experimentally validated with sufficient measurements, and the secondly, the MHPA design they studied is typically used in many similar solar thermal collectors by recent research25,29.

The CFD model geometry consists of a single heat-collection unit with six key components: glass cover (modeled as “wall” boundary condition), MHPA (length = 1.75 m, width = 0.08 m, thickness = 0.003 m). air duct, and fins, whose detailed dimensions are listed out in Fig. 4(a), which is referenced from literature referrence27.

Solar energy first passes through the glass cover and is absorbed by the MHPA, which conducts the heat horizontally. The aluminum fins conduct this heat, reaching higher temperatures. As ambient air flows through the duct and across these heated fins, the thermal energy transfers from the fins to the air. This heated air can then be used for food drying applications, as shown in Fig. 4(b) and (c).

The study used commercial CFD software ANSYS Fluent Cloud platform with 32 cores for carrying out model simulations. The computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model employs Navier-Stokes equations for incompressible flow. Continuity is enforced through ∇·u = 0, which ensuring mass conservation. Momentum conservation follows:

where u is velocity, p is pressure, is \(\:{\upmu\:}\) dynamic viscosity, and g represents gravitational acceleration. Energy transport is governed by:

where \(\:{C}_{p}\) is specific heat capacity, k is thermal conductivity, and S represents source terms including solar radiation. The buoyancy-driven natural convection employs the Boussinesq approximation for density (ρ) variation:

which couples temperature variations to density changes. \(\:{\rho\:}_{0}\) is density, T is temperature, β is thermal expansion coefficient, and T₀ is reference temperature, Turbulence effects are captured using appropriate RANS models with wall functions for near-wall treatment.

The boundary conditions are defined as follows: incident solar radiation is applied as an energy density heat source through the MHPA; the glass cover external surface experiences natural convection with ambient air while its internal surface undergoes coupled radiation-convection interactions, with heat convection governed by the surface heat transfer coefficient; heat conduction occurs at the absorber-MHPA evaporation section interface; the MHPA is modeled as a high-efficiency heat conductor incorporating phase change effects; the air duct system features fluid-solid coupled interfaces between cooling fins and airflow, with air entering at ambient temperature through a velocity inlet boundary and exiting through a free outflow boundary; and the back cover is treated as adiabatic. This configuration comprehensively captures all relevant heat transfer mechanisms: radiation, natural convection, conduction, phase change, and forced convection, referring to the details in Table 1, where the above discussed boundary conditions are summarized accordingly.

It is important to ensure that mesh is refined sufficiently so that model solution does not change further with refinement of mesh. The study is firstly carried out with fewer mesh elements, and then gradually refined mesh until to a point of further mesh refinement does not change the solution.

Polyhedral mesh is generated, and mesh is further refined locally at the areas of interest (e.g., conjugate heat transfer surfaces) to ensure that turbulent flow and heat transfer mechanism is captured.

Evaluating thermal efficiency

In the present study, CFD model with referring to the experiment set up and numerical model methodology by is developed by using two equation - Reynold Averaged Naver-Stokes (RANS) model, k-epsilon model, to consider the turbulent airflow within the solar thermal collector27. In the reference research27the thermal efficiency has been studied with evaluating a few parameters (e.g., fin spacing, ambient air temperature, and air inlet velocity). However, due to nature that CFD model is expensive to run and requires high performance computing resources, these studies were evaluated with data only under limited design and process conditions. The design and process evaluation of solar thermal collector involves the interaction of many material, design, and process parameters, and thus a more systematic approach that involves large sets of data would help researchers to provide more insights to the thermal efficiency and complex material, design, and process conditions.

Thermal efficiency, η, is an important parameter to evaluate the performance of solar thermal collector, which can be expressed as27:

where \(\:\dot{m}\:\)is the mass flow rate of air, \(\:{T}_{i}\) is the inlet air temperature that enters the solar collector, \(\:{T}_{o}\) is outlet air temperature that enters into the container for drying food, A is the absorber area, I is the solar radiation intensity, and \(\:{C}_{p}\) is the specific heat of air. Thus, in other words, η is the ratio of utilized heat energy that used for heating up the air in the solar thermal collector to the total received solar energy via radiation.

Generating datasets

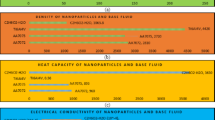

The effectiveness of machine learning model greatly depends on the selection of appropriate input parameters. Thus, to effectively evaluate thermal efficiency, the material property and process condition need to be carefully chosen to ensure that the developed machine learning model is built upon has relevant and important input parameters for output of thermal efficiency. Thus, six input parameters that describes the material properties and process condition are chosen: Air inlet velocity from ambient environment (\(\:{U}_{i})\), thermal conductivity of metal fins (\(\:{K}_{f})\), heat transfer coefficient of glass cover (\(\:{H}_{g})\), air inlet temperature (\(\:{T}_{i})\), equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA (\(\:{K}_{m})\), and power density absorbed by the thermal collector (\(\:{P}_{tc})\), which comes from the solar radiation. These input parameters determine numerical condition, which are the specific values of parameters that define the exact mathematical setup for each CFD simulation run. were chosen as input for developing machine learning model. Figure 5 shows the schematic view of the machine learning networks in this study as we discussed above. The chosen input parameters were fed into as input of the system and different machine learning techniques will be applied in the network for calculating the thermal efficiency of solar thermal collector, as shown in Fig. 5.

The above input parameters were identified through a systematic physics-based approach that captures all major heat transfer mechanisms in the solar thermal collector system. The three material properties were selected: thermal conductivity of metal fins (\(\:{K}_{f})\:\)affects heat conduction from the absorber to the air, the equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA (\(\:{K}_{m})\) determines heat transfer efficiency across the heat pipe system, and the heat transfer coefficient of glass cover (\(\:{H}_{g})\) influences heat losses to the environment. Three operational parameters complete the set: air inlet velocity (\(\:{U}_{i})\) controls the convective heat transfer rate, air inlet temperature (\(\:{T}_{i})\) sets the baseline thermal conditions, and power density \(\:{(P}_{tc}\)) represents the absorbed solar radiation.

Aside from selecting effective input parameters, an appropriate parameter varying window (defined as the specific range of values within which each input parameter is allowed to vary when generating the CFD simulation datasets) of these input parameters needs to be well defined before generated large set of CFD data because inappropriate parameter varying window will results in unphysical results, and if those results were used in training data sets, the accuracy of developed machine learning model would be compromised or negatively affected.

The selection of machine learning algorithms followed a systematic approach from simple to complex methods to comprehensively evaluate modeling capabilities for the non-linear thermal system. Linear regression (LR) was chosen as the baseline model due to its interpretability and computational efficiency, providing a benchmark for comparing more sophisticated approaches. Support vector regression (SVR)32 was selected for its proven ability to handle non-linear relationships through kernel functions while maintaining robustness against overfitting, particularly valuable given the multi-dimensional parameter space with complex interactions. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) model33 were implemented as they excel at capturing intricate non-linear patterns in thermal systems through multiple hidden layers, offering the potential for highest accuracy when sufficient training data is available.

Extensive datasets containing 935 numerical cases were modeled by using 32 cores running in parallel by leveraging the available computing resources. The 935 numerical cases were used in the present study through balancing the fact that machine learning models require generating sufficient large number of training datasets and one needs to keep computational cost of running CFD model cases affordable.

Linear regression model

The present study firstly developed linear regression (LR) model as it is the simplest machine learning model. LR model can be categorized into simple LR and multiple LR model34. Simple LR has one independent variable while multiple regression includes several explanatory variables. The basic mathematical form of multiple regression model can be expressed as follows35:

where \(\:{b}_{0}\) is a constant term, \(\:{b}_{1}\), \(\:{b}_{2}\),…, \(\:{b}_{k}\) are coefficients of regression terms, and e is sum of errors.

The cost function for LR, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), which can be written in the below form:

, where N is number of data points, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is observed value.

In addition to RMSE, “R-squared” (R²), referred to as the coefficient of determination, is a statistical metric employed in machine learning to assess the effectiveness of a regression model. It quantifies the degree to which the model accurately represents the data by evaluating the fraction of variance in the dependent variable that is accounted for by the independent variables.

R² can be mathematically expressed by considering the Sum of Squares of Errors (SSE) or the Sum of Squared Residuals (SSR) to the Total Sum of Squares (TSS), which can be detailed as below:

where, ESS is regression sum of squares:

TSS is the regression sum of squares for total:

Based on the above description of RMSE and R², one can note that when evaluating the adequacy of a model in relation to a dataset, it is beneficial to compute both the RMSE and the R² value, as each metric provides distinct insights. RMSE indicates the average deviation between the predicted values generated by the regression model and the actual observed values. Conversely, R² measures the extent to which the predictor variables account for the variability in the response variable.

Therefore, the present study will evaluate both RMSE and R² for comparing the performance of different machine learning models. The architecture diagram of LR model is detailed in Fig. 6.

Support vector regression model

Support vector regression (SVR) model is chosen in this study as it is popular for addressing regression challenges, primarily due to their ability to model data with non-linear relationships through the use of the kernel trick36. SVR model is frequently utilized with various kernel functions to transform the input space into a higher-dimensional feature space. This transformation introduces non-linearity into the solution, enabling the execution of LR within the feature space37. Taking example of linear functions for best fit function:

With the objective to minimize \(\:\frac{1}{2}{‖w‖}^{2}\) and constraints:

where \(\:\epsilon\:\) defines a margin of tolerance, w and b are the weights and bias, respectively .

Figure 7 illustrates the architecture of SVR model used to predict solar thermal collector efficiency. The model transforms the six-dimensional input space, which is through a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel with hyperparameters C = 1.0, γ=’scale’, and ε = 0.1. This kernel mapping projects the data into a high-dimensional feature space where a linear regression function can be fitted. The SVR algorithm identifies support vectors (critical data points) that define the regression function within an ε-insensitive tube, allowing for controlled prediction error tolerance and the model ultimately outputs thermal efficiency (η), which is detailed in Figure xx.

Artificial neural networks model

Artificial Neural networks (ANN) model is a class of machine learning algorithms designed to replicate the information processing functions of the human brain. The objective of ANN is the thermal efficiency. Hidden layers are placed in between the objective and input layers for prediction. In the present model, the activation function for hidden layers uses Rectified Linear Unit Function (RELU). The hyperparameters (e.g., L2 penalty parameter) is used as default within scikit-learn library with seven input parameters are input layer and thermal efficiency is the objective38.

ANN model develops rapidly in recent years. ANN can be mathematically considered as a nonlinear regression model \(\:f\left(x\right)=\phi\:(w,\:x)\), where \(\:\phi\:\) is a nonlinear model function and w is the vector that contains the parameters in which x is known as inputs. The basic units of ANN, known as perceptron, can be computed as:\(\:f\left(x\right)=\phi\:({w}^{T},\:x)\), where the nonlinear function \(\:\phi\:\) is called activation function. The training of perceptron model is conducted through the updating of weights as follows39:

where \(\:{\upeta\:}\) is the learning rate.

The generation of comprehensive datasets involved a methodical approach leveraging validated CFD modeling techniques. After establishing a baseline CFD model validated against experimental data from27. Random sampling within these carefully considered parameter ranges was employed to avoid biasing the results, generating 935 distinct simulation cases. Each case represented a unique combination of air inlet velocity, fin thermal conductivity, glass cover heat transfer coefficient, inlet temperature, MPHA equivalent thermal conductivity, and power density for thermal conversion. These simulations, executed in parallel across 32 cores, solved the full 3D thermal-fluid physics with k-epsilon turbulence modeling, capturing the complex interactions between parameters and producing a robust dataset that spans the practical operating space of solar thermal collectors.

As shown in Fig. 8 for the architecture diagram in the present research, multilayer perceptron (MLP) ANN model is used to predict solar thermal collector efficiency. The feed-forward network consists of an input layer with six neurons, two hidden layers with 100 and 50 neurons respectively (both using ReLU activation functions to capture non-linear relationships), and an output layer with a single neuron using linear activation to represent thermal efficiency (η).

Discussion

CFD model analysis

Figure 9 shows the mesh independence study, where we the average temperature of the fins is monitored across different mesh element numbers. It can be observed from Fig. 8 that the result does not noticeably change after mesh element number reaches approximately 1.47 million. Further increasing the mesh element numbers changes the monitored results very little. Thus, 1.47 million mesh elements are used in the present study.

CFD physics model is used to perform the above discussed solar thermal collector that essential for drying food, which is developed by referring to reference literature27. Figure 10 shows the temperature distribution contour of a cut cross-section through the mid-plane of the 3D steady state thermal-flow model under three different air inlet temperature conditions. In the physics based CFD model, we assume that the incoming air from the ambient is 3.3 m/s under the temperature of 280 K, 285 K, and 312 K, respectively. The glass cover has heat transfer coefficient of 5 W/\(\:{\text{m}}^{2}\text{K}\). The metal fins are considered to be made of aluminum, whose thermal conductivity is estimated to be 202.4 W/\(\:\text{m}.\text{K}\). The total absorbed solar thermal energy is 105 W (e.g., uses the same sun radiation condition as in27 ).

Based on the temperature contour plots shown in Fig. 10, we can observe how different inlet air temperatures affect the heat transfer and outlet conditions. In Fig. 10a with the lowest inlet temperature of 280 K, there is a significant temperature rise as shown by the color gradient from blue to red, indicating effective heat transfer from the fins to the air. Figure 10b with an inlet temperature of 285 K shows a similar pattern but with a slightly smaller temperature differential. However, in case of Fig. 10c where the inlet air temperature is already high at 312 K, the temperature change is minimal as indicated by the relatively uniform green coloring, suggesting reduced heat transfer effectiveness due to the smaller temperature difference between the fins and the incoming air. This comparison clearly demonstrates that the heat transfer rate is more efficient when there is a larger temperature differential between the inlet air and the heated fins.

As shown in Fig. 10, the advantage of physics based CFD model is its capability to present a full 3D virtual view of the temperature distribution. The detailed analysis could be carried out based on CFD model results based on certain design and process parameters. However, CFD models take a long time to run and usually requires high performance computing resources, which are sometimes not always available to researchers. When running one case of CFD, only a certain combination of design and process parameters can be studied and analyzed, which limits the knowledge of understanding and optimization of design and process for solar thermal collector efficiency in the present study. This is the reason why the authors of this present study propose a hybrid combined method to generate large datasets of CFD model data and use them for machine learning analysis to understand more in-depth insights of parameters for solar thermal collector process and design.

It is important to understand that developing an effective machine learning model depends on obtaining high-quality training datasets. Thus, the accuracy of the baseline physics based CFD model is validated against experiment from literature before generating extensive datasets.

Figure 11 shows the comparison between the experiment measurements by literature refence27 and present CFD model results. Figure 11 presents the relationship between air inlet temperature and thermal efficiency, comparing experimental data (solid triangles) and model predictions (hollow circles). There is a clear inverse relationship between inlet temperature and thermal efficiency - as the inlet temperature increases from 6 to 20 °C, the thermal efficiency decreases from approximately 0.6 to 0.5. The model predictions align very closely with the experimental results across all three measured points, validating the accuracy of the model. This means that the CFD model presented in this study is capable to effectively model the solar thermal collector with validated accuracy.

Comparison between experiment of27 and present CFD model results.

Statistical analysis

Figure 12 shows the distribution of thermal efficiency for all generated 935 numerical cases through CFD model runs. It is interesting to see that the histogram of thermal efficiency data reveals a primarily normal distribution with a slight left skew, centered around 65–67% efficiency. The distribution spans from approximately 30–80% efficiency, with most cases falling between 55% and 75%. The data shows a single peak (unimodal) with the highest frequencies (exceeding 60 occurrences) near the 65–67% efficiency range. It is important to note that the smooth, bell-shaped distribution and large sample size suggest reliable and consistent system performance. This distribution pattern in Fig. 12 provides strong evidence that the solar thermal collector system maintains stable performance, typically operating at 60–70% thermal efficiency.

Table 2 shows the statistical overview of the inputs and outputs from the CFD datasets. As mentioned above, a total of 935 CFD cases were ran with varying material properties and process conditions that determined by the six input parameters (\(\:{U}_{i}\), \(\:{K}_{f}\), \(\:{H}_{g}\), \(\:{T}_{i}\), \(\:{K}_{m}\), and \(\:{P}_{tc}\)). Complete 3D CFD simulations solve the physical model of temperature and velocity field of the solar thermal collectors. Outputs (\(\:{T}_{o\:}\)and \(\:\dot{m}\)) are generated from these CFD simulation runs and can be used to calculate thermal efficiency (\(\:{\upeta\:}\)).

Correlation analysis

It could notice several key relationships from Fig. 13, which presents correlation analysis of input parameters to thermal efficiency. Among the six input parameters, “air inlet velocity (r = 0.512)” and “equivalent thermal conductivity of MHPA (r = 0.527)” demonstrate the strongest positive relationships with thermal efficiency, showing clear upward trends despite some scatter. “Air inlet temperature” exhibits a moderate negative correlation (r = − 0.181), while “thermal conductivity of metal fins (r = − 0.018)”, “heat transfer coefficient of glass cover (r = − 0.006)”, and “power density (r = − 0.14)” show minimal to weak correlations with efficiency. The generally spanned values of thermal efficiency in Fig. 13 is between 0.3 and 0.8, and more clustered between 0.5 and 0.7.

From Fig. 13, it also shows that the fluid dynamics parameters (e.g., air velocity and mass flow rate) appear to be the most critical factors in determining thermal efficiency. Temperature-related parameters show significant impact, with inlet temperature having a notable negative correlation. Material properties (thermal conductivity of fins and glass cover) have relatively minor direct impacts on thermal efficiency. Thus, one should focus on optimizing air flow parameters (e.g., air velocity and mass flow rate) as they have the strongest positive impact on efficiency, and consider the trade-off with inlet temperature, as lower temperature appear to benefit efficiency while MPHA thermal conductivity shows moderate importance.

Correlation analysis of input parameters affecting thermal efficiency in solar thermal collectors (a) Air inlet velocity, (b) Thermal conductivity of metal fins, (c) Heat transfer coefficient of glass cover, (d) Air inlet temperature, (e) Equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA, and (f) Power density for thermal conversion.

Comparison of model accuracy across different machine learning models

Three different machine learning models- LR, SVR, and ANN model are compared for their accuracy in predicting the thermal efficiency in Jupyter Notebook by coding in Python.

CFD model datasets are shuffled firstly and divided into training, validating and testing datasets. In the present study, the total datasets are split by 70% for training, 15% for validation during model development and hyperparameter tuning, and 15% for final testing to evaluate generalization performance, which helps to ensure our models are not overfitting and provides more reliable performance metrics.

Figure 14 compares the above three machine learning models’ performance. All three models show moderate predictive capability with notable differences in accuracy. LR model performs best (R² = 0.6134, RMSE = 0.056), followed by SVR (R² = 0.5096, RMSE = 0.0631), and ANN model (R² = 0.4098, RMSE = 0.0692). All models show significant scatter around the ideal prediction line (red dashed), particularly in the mid-range values, indicating room for improvement in predictive accuracy.

Optimization of ANN model

As noted above, all three different machine learning methods do not seem to provide a high enough accuracy. LR model performs the best, however, with only R² =0.6134. The other two methods, SVR and ANN, could be further optimized intending to achieve higher accuracy of performance for prediction. Thus, Grid Search Cross-Validation was implemented to optimize hyperparameters for both SVR and ANN models. For SVR, the authors optimized the regularization parameter (C: 0.1–100), gamma values (scale, auto, 0.1, 0.01), kernel types (rbf, polynomial), and epsilon values (0.01–0.2), which aims to provide advanced testing and control, see the summary of the improvement effort in Table 3.

Similarly, for the ANN model, different architectures were tested for varying hidden layers, activation functions (relu’, ‘tanh’), learning rates (0.001–0.01), and batch sizes (32–128), with maximum iterations set to 2000. Both models employed 5-fold cross-validation and parallel processing for efficient computation, see Table 4 for details of the summary.

These optimizations improved model accuracy, resulting in higher R² scores and lower RMSE values compared to baseline models for that discussed and analyzed above. Both optimized models demonstrate strong predictive accuracy with high R² values and low RMSE. Figure 15 reveals that both models follow the ideal prediction line (red dashed) closely, with some minor deviations at extreme values. While SVR shows slightly better statistical metrics, both models appear to be robust predictors, outperforming LR model from the above.

To summarize the above discussion, Table 5 shows the statistical performance metrics related to the prediction across the models. As can be shown from Table 5, hyperparameter optimization dramatically improved model performance. While LR model showed the best baseline results (R² = 0.6134), optimized SVR and ANN models achieved superior accuracy with R² values of 0.96 and 0.94 respectively. The optimized SVR model demonstrated the highest performance, making it most suitable for thermal efficiency prediction.

Impact of dataset volume

In the present study, machine learning models are used to reveal distinctive performance characteristics and scaling behaviors across varying dataset sizes (n = 100 to 800) for thermal efficiency prediction in complex heat transfer systems. ANN demonstrate superior predictive capabilities, achieving an R² value of 0.95 and minimal relative error of 2% at n = 800, attributable to their ability to capture complex non-linear thermal interactions. SVR maintains robust intermediate performance (R²≈0.85, relative error 4%), suggesting its utility as a reliable baseline model, particularly when computational resources are constrained. The poor performance of linear regression (R²<0.65, relative error 8%) underscores the inherent non-linear complexity of the thermal system’s underlying physics.

From Fig. 16, it can be noticed that a critical transition region is identified between 100 and 300 samples, where all models exhibit rapid error reduction, followed by asymptotic convergence beyond 600 samples. This behavior indicates an optimal dataset size threshold for resource-efficient model deployment. The ANN model’s performance advantage becomes particularly pronounced at larger dataset sizes (n > 400), while maintaining competitive accuracy (relative error ≈ 4%) even under data-constrained conditions (n = 200). The RMSE trends further corroborate these findings, with ANN model achieving the most substantial reduction (0.09 to 0.02) across the dataset size range.

Based on Fig. 16, it is recommended using ANN for production environments with adequate data collection capabilities (> 600 samples) to achieve optimal accuracy. For rapid prototyping or systems with limited data availability (< 300 samples), SVR presents a more practical choice, offering robust performance without extensive data requirements. The analysis suggests focusing efforts on obtaining 400–600 samples, as this range represents the optimal balance between model accuracy and data acquisition costs. Future work should investigate the impact of feature engineering and ensemble methods to potentially enhance SVR performance for smaller datasets.

Interpretability of developed machine learning model

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis reveals distinct patterns of feature importance and their impacts on machine learning model predictions for output of interest (e.g., thermal efficiency in the present study). It provides a mathematical framework for interpreting machine learning model predictions by assigning each feature an importance value based on game theory principles40. It addresses the “black box” nature of machine learning models by quantifying both individual and interactive effects of input variables on model outputs, enabling researchers to validate model behavior against physical principles and derive actionable insights for system optimization. Since it has been shown that SVR has more practical and robust performance without extensive data requirements for the present study, SHAP analysis is performed on SVR model for interpretability study. Figure 17(a) demonstrates that equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA and air inlet temperature are the most influential parameters, with mean SHAP values of 0.042 and 0.038 respectively, indicating their dominant role in determining system efficiency. Inlet temperature and power density show moderate importance (SHAP values ≈ 0.015), while thermal conductivity of metal fins and heat transfer coefficient of glass cover exhibit minimal impact (SHAP values < 0.005). The feature impact distribution in Fig. 17(b) further elucidates that thermal conductivity of metal fins) and air inlet temperature display strong positive correlations with efficiency at high values (red points) and negative correlations at low values (blue points), suggesting a nonlinear relationship. Notably, inlet temperature shows a more complex pattern with both positive and negative impacts distributed across its range, indicating potential interaction effects with other parameters. Power density for thermal conversion demonstrates a relatively symmetric impact distribution around zero, suggesting a more stable influence on efficiency predictions. Thus, it could be suggested that (1) prioritizing the optimization of equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA and air inlet temperature parameters during system design, (2) implementing adaptive control strategies for inlet temperature to account for its variable effects, and (3) considering the development of simplified models for preliminary design stages that focus primarily on the two dominant parameters while maintaining acceptable accuracy. Future work should investigate the specific interaction mechanisms between inlet temperature and other parameters to enhance model robustness.

In Fig. 17, The SHAP analysis reveals that MHPA thermal conductivity and air inlet temperature dominate thermal efficiency, which aligns with fundamental heat transfer physics. MHPA conductivity controls the rate of heat transfer from the solar-heated evaporator to the condenser section, essentially determining how effectively the system can transport thermal energy. Air inlet temperature creates the temperature differential that drives convective heat transfer—lower inlet temperatures increase the temperature difference between the heated fins and incoming air, enhancing heat transfer rates.

SHAP analysis of SVR model for thermal efficiency prediction: (a) feature importance ranking based on mean absolute SHAP values, demonstrating the relative contribution of each input parameter to model predictions; (b) SHAP value distribution plots showing the impact and directionality of individual features, where color indicates feature value.

To get a more comprehensive understanding of how SHAP values vary with the input variables, SHAP dependence analysis is performed to study parameter interactions in thermal system efficiency. Figure 18a demonstrates the non-linear relationship of equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA, transitioning from negative impact below 20,000 W/m-K to positive influence beyond 40,000 W/m-K, with higher air velocities enhancing this positive effect. In addition, Fig. 18b shows power density for thermal conversion’s negative correlation with thermal efficiency beyond 1.0 × 10⁶ W/m², though higher air inlet temperatures moderate this negative impact. Figure 18c illustrates the heat transfer coefficient (HTC) of glass cover has transition from positive (0.015) to negative (− 0.015) impact as values increase, with stronger interaction effects at higher glass cover HTC values (> 20 W/m²-K). Figure 18d reveals air inlet temperature’s predominantly negative influence above 265 K, with the heat transfer coefficient (HTC) of glass cover moderating this effect. Figures 18e, f further confirm these relationships: equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA shows a distinct transition from negative (− 0.20) to positive (0.05) impact up to 40,000 W/m-K with high air inlet velocity enhancement, while power density for thermal conversion exhibits increasingly negative correlation beyond 1.5 × 10⁶ W/m², moderated by higher air inlet temperatures (> 275 K).

In Fig. 18, the dependence plots demonstrate critical physical transitions in the thermal system. MHPA conductivity shows a negative impact below 20,000 W/m-K because insufficient heat transport limits system performance, but becomes beneficial above 40,000 W/m-K where rapid heat transfer enables efficient energy collection. Power density exhibits negative correlation beyond 1.0 × 10⁶ W/m² due to thermal saturation—excessive solar input cannot be effectively transferred, causing heat accumulation and reduced efficiency. The glass cover heat transfer coefficient transition reflects the balance between beneficial heat retention (low values) and excessive heat loss to ambient (high values).

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) value dependence analysis for SVR model of thermal system efficiency with interaction of (a) equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA with air velocity; (b) power density for thermal conversion with inlet temperature; (c) heat transfer coefficient of glass cover with power density for thermal conversion; (d) air inlet temperature with heat transfer coefficient of glass cover; (e) equivalent thermal conductivity of MPHA with air velocity; and (f) power density for thermal conversion with air inlet temperature.

Table 6 provides the optimized outcomes derived from our comprehensive surrogate modeling approach. Based on the comprehensive parameter analysis conducted through our surrogate modeling approach, we can establish optimal operational parameters for maximizing thermal efficiency in solar collectors. The SHAP values reveal critical transi-tion thresholds where parameters shift from negative to positive influence on system per-formance. These findings, which are summarized in Table 6, represent data-driven opti-mization guidelines derived from interpreting our surrogate models rather than conven-tional sensitivity analysis. The strong interactions between parameters, particularly at their transition points, indicate that system optimization requires careful consideration of parameter combinations, with potential for extended operating ranges when leveraging compensatory effects between interacting parameters.

Entropy analysis

Entropy analysis quantifies randomness in data systems using Shannon’s formula, which measures information content and predictability41. In the present study, Fig. 19 employs Mutual Information (MI) to quantify information sharing between input variables and thermal efficiency. MI measures how much knowing the value of one variable reduces uncertainty about another variable, capturing both linear and non-linear dependencies between parameters. The normalized MI values shown in Fig. 19 indicate the percentage of uncertainty reduction in thermal efficiency when each parameter is known. MPHA thermal conductivity demonstrates the highest normalized mutual information (~ 20%), followed by air inlet temperature (~ 17%), air velocity (~ 14%), and three parameters each contributing ~ 12–13%: glass cover heat transfer coefficient, thermal conversion power density, and metal fin thermal conductivity. From an entropy perspective, these values represent potential uncertainty reduction in efficiency predictions when each parameter is known. Consistent with previous machine learning model results, the dominant influence of MPHA conductivity indicates it provides the greatest entropy reduction, establishing it as the critical design parameter. This information-theoretic approach reveals that optimizing MPHA properties and inlet temperature would most effectively increase system predictability and performance, which provides clearer design priorities than conventional sensitivity analyses.

The entropy-based sensitivity in Fig. 19 reveals the information content each parameter contributes to predicting thermal efficiency. MHPA thermal conductivity’s highest mutual information (~ 20%) reflects its role as the primary heat transfer pathway connecting solar collection to air heating. Air inlet temperature (~ 17%) and velocity (~ 14%) rank next because they control the convective heat removal rate—the system’s ability to extract collected thermal energy. The lower importance of other parameters indicates they represent secondary heat transfer mechanisms or boundary conditions rather than primary energy transport pathways.

Future research direction

The present research provides a computational methodology to combine CFD model and machine learning for evaluating thermal efficiency of solar thermal collector. There may be some limitations of the present research and could extend this approach for future improvement by researchers.

On the level of process condition and system design, present research studied the impact of six input parameters with fixed solar thermal collector design for indirect solar food drying process. Future research could expand the training dataset by incorporating more diverse environmental conditions and operational scenarios (e.g., system physical dimensions, structure components, impact of humidity, seasonal variation, and geographical location). More advanced deep learning architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for temporal performance prediction could be explored or developing ensemble methods combining multiple machine learning algorithms to improve prediction accuracy. In addition, the impact of structural design (e.g., different MHPA configurations and geometries on system performance) can be studied. In addition, the relationship between collector thermal efficiency and food drying quality could be further explored by future work.

The hybrid CFD-ML methodology is potentially transferrable to other thermal systems because it addresses fundamental challenges common across heat transfer applications: high computational costs of physics-based simulations and the need for rapid design optimization. The approach addresses the underlying physics (conservation laws) governs all thermal systems and parameter-to-performance relationships typically exhibit similar non-linear characteristics. However, successful application requires significant initial investment in data generation—our study shows optimal performance needs 600 + CFD simulations, with critical improvements occurring between 100 and 300 samples. This data requirement represents the primary limitation for broader adoption, as generating high-fidelity CFD datasets demands substantial computational resources and domain expertise. Additionally, the model’s accuracy is bounded by the quality and representativeness of training data; systems operating outside the trained parameter ranges may yield unreliable predictions. Despite these constraints, once the initial dataset is established, the ML models enable rapid exploration of design spaces that would be computationally prohibitive using CFD alone. Future research should focus on developing transfer learning approaches to reduce data requirements for new applications and establishing standardized validation protocols for cross-domain implementation.

Conclusions

In this present research work, we present a hybrid methodology to address a persistent challenge in thermal system design. In the present study, we introduced an innovative hybrid CFD-ML methodology that revolutionizes solar thermal collector optimization for food drying applications. By training machine learning models on 935 CFD simulations, the approach achieves exceptional predictive accuracy (R² = 0.95) while dramatically reducing computational time. The key innovation lies in using SHAP analysis to make the ML models interpretable, revealing that MHPA thermal conductivity and air inlet temperature are the critical design parameters, with optimal thresholds at > 40,000 W/m-K and < 265 K respectively. This methodology transforms traditionally time-intensive thermal system optimization into a rapid, data-driven process while maintaining the physical understanding essential for engineering applications. The key conclusions are summarized as follows:

-

The hybrid methodology achieved high accuracy (R² = 0.95) while drastically reducing computational time compared to traditional CFD approaches.

-

Thermal system performance is governed by complex parameter interactions rather than individual factors, which challenges the traditional approach of isolated parameter optimization.

-

Specific design thresholds were identified, including optimal MHPA thermal conductivity above 40,000 W/m-K and air inlet temperature below 265 K.

-

In the analysis of impact of data entry volumes, using 100–300 samples shows model errors rapidly decrease, with ANN model showing superior performance at larger dataset sizes (> 400), while recommending ANN model for production environments with > 600 samples and SVR for limited data scenarios (< 300 samples), with 400–600 samples representing the optimal balance between accuracy and data acquisition costs.

-

SHAP analysis provided interpretable insights into the “black box” of machine learning predictions, which provides data-driven modeling with physical understanding and optimized process conditions.

-

Entropy analysis identified MPHA thermal conductivity as the most influential parameter (~ 20% mutual information), followed by air inlet temperature (~ 17%) and air velocity (~ 14%).

In addition, the present study provides innovative use of entropy analysis quantifies parameter importance (MHPA thermal conductivity: ~20% uncertainty reduction), providing an information-theoretic framework that can be transferred to other thermal system optimizations, advancing sustainable energy design methodologies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fernandes, L. & Tavares, P. B. A review on solar drying devices: Heat transfer, air movement and type of chambers. Solar 4, 15–42 (2024).

Fernandes, L., Fernandes, J. R. & Tavares, P. B. Design of a friendly solar food dryer for domestic over-production. In Solar 2, 495–508. (2022).

Ekechukwu, O. V. & Norton, B. Review of solar-energy drying systems II: An overview of solar drying technology. Energy. Conv. Manag. 40 (6), 615–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-8904(98)00093-4 (1999).

Esper, A. & Mühlbauer, W. Solar drying—an effective means of food preservation. Renew. Energy. 15 (1), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(98)00143-8 (1998).

Fernandes, J. C. S., Nunes, A., Carvalho, M. J. & Diamantino, T. Degradation of selective solar absorber surfaces in solar thermal collectors–An EIS study. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 160 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2016.10.015 (2017).

Zayed, M. E. Recent Advances in Solar Thermal Selective Coatings for Solar Power Applications: Technology Categorization, Preparation Methods, and Induced Aging Mechanisms. In Applied Sciences 14. (2024).

Dj Azzawı, I., Azeez, K., Ahmed, R. I. & Obaıd, Z. A. Heat transfer enhancement and applications of thermal energy storage techniques on solar air collectors: A review. J. Therm. Eng. 9 (5), 1356–1371. https://doi.org/10.18186/thermal.1377246 (2023).

Vahidhosseini, S. M., Rashidi, S., Hsu, S. H., Yan, W. M. & Rashidi, A. Integration of solar thermal collectors and heat pumps with thermal energy storage systems for Building energy demand reduction: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage. 95, 112568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.112568 (2024).

Hamdan, M., Abdelhafez, E., Ajib, S. & Sukkariyh, M. Improving thermal energy storage in solar collectors: A study of aluminum oxide nanoparticles and flow rate optimization. In Energies 17. (2024).

Tian, Y. & Zhao, C. A review of solar collectors and thermal energy storage in solar thermal. Appl. Energy. 104, 538–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.11.051 (2013).

Faddouli, A. et al. Comparative study of a normal solar water heater and smart thermal/thermoelectric hybrid systems. Mater. Today Proc. 30, 1039–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.04.499 (2020).

Mohana, Y. et al. Solar dryers for food applications: Concepts, designs, and recent advances. Sol. Energy. 208, 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.07.098 (2020).

Suman, S., Khan, M. K. & Pathak, M. Performance enhancement of solar collectors—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 49, 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.04.087 (2015).

Arabhosseini, A., Samimi-Akhijahani, H. & Motahayyer, M. Increasing the energy and exergy efficiencies of a collector using porous and recycling system. Renew. Energy. 132, 308–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.07.132 (2019).

Simo-Tagne, M. et al. Numerical analysis and validation of a natural convection mix-mode solar dryer for drying red Chilli under variable conditions. Renew. Energy. 151, 659–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.11.055 (2020).

Singh, R., Salhan, P. & Kumar, A. CFD modelling and simulation of an indirect forced convection solar dryer. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 795 (1), 012008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/795/1/012008 (2021).

Güler, H. Ö. et al. Experimental and CFD survey of indirect solar dryer modified with low-cost iron mesh. Sol. Energy. 197, 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.01.021 (2020).

Norton, T., Tiwari, B. & Sun, D. W. Computational fluid dynamics in the design and analysis of thermal processes: A review of recent advances. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 53 (3), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2010.518256 (2013).

Demissie, P. et al. Design, development and CFD modeling of indirect solar food dryer. Energy Procedia. 158, 1128–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2019.01.278 (2019).

Behera, D. D., Mohanty, R. C. & Mohanty, A. M. Thermal performance of a hybrid solar dryer through experimental and CFD investigation. J. Food Process Eng. 46 (8), e14386. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpe.14386 (2023). accessed 2024/12/01).

Jain, R., Paul, A. S., Sharma, D. & Panwar, N. L. Enhancement in thermal performance of solar dryer through conduction mode for drying of agricultural produces. Energy Nexus. 9, 100182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nexus.2023.100182 (2023).

Abushanab, W. S., Zayed, M. E., Sathyamurthy, R., Moustafa, E. B. & Elsheikh, A. H. Performance evaluation of a solar air heater with staggered/longitudinal finned absorber plate integrated with aluminium sponge porous medium. J. Build. Eng. 73, 106841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106841 (2023).

Zayed, M. E. et al. Recent progress in phase change materials storage containers: Geometries, design considerations and heat transfer improvement methods. J. Energy Storage. 30, 101341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101341 (2020).

Kabeel, A. E., Khalil, A., Shalaby, S. M. & Zayed, M. E. Experimental investigation of thermal performance of flat and v-corrugated plate solar air heaters with and without PCM as thermal energy storage. Energy. Conv. Manag. 113, 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.01.068 (2016).

Ranjan Tamuli, B. & Nath, S. Analysis of micro heat pipe array based evacuated tube solar water heater integrated with an energy storage system for improved thermal performance. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress. 41, 101801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2023.101801 (2023).

Zhao, Y. H. & Diao, Z. K. YH. Heat pipe with micro-pore tubes array and making method thereof and heat exchanging system. (2011).

Zhu, T. & Zhang, J. A numerical study on performance optimization of a micro-heat pipe arrays-based solar air heater. Energy 215, 119047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119047 (2021).

Abdelkader, T. K. et al. Flat micro heat pipe-based shell and tube storage unit for indirect solar dryer: A pilot study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (34), 46385–46396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27851-z (2024).

Mathew, A. A. & Thangavel, V. A novel thermal energy storage integrated evacuated tube heat pipe solar dryer for agricultural products: performance and economic evaluation. Renew. Energy. 179, 1674–1693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.07.029 (2021).

Lamidi, R. O., Jiang, L., Pathare, P. B., Wang, Y. D. & Roskilly, A. P. Recent advances in sustainable drying of agricultural produce: A review. Appl. Energy. 233–234, 367–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.044 (2019).

Zhu, T., Diao, Y., Zhao, Y. & Ma, C. Performance evaluation of a novel flat-plate solar air collector with micro-heat pipe arrays (MHPA). Appl. Therm. Eng. 118, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.02.076 (2017).

Vakili, M. & Salehi, S. A. A review of recent developments in the application of machine learning in solar thermal collector modelling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (2), 2406–2439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-24044-y (2023).

Kler, R. et al. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in the food industry: A sustainable approach. J. Food Qual.. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8521236

Rong, S. & Bao-wen, Z. The research of regression model in machine learning field. MATEC Web Conf. 176 https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201817601033 (2018).

Maulud, D. & Abdulazeez, A. A. Review on linear regression comprehensive in machine learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends. 1, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.38094/jastt1457 (2020).

Üstün, B., Melssen, W. J. & Buydens, L. M. C. Visualisation and interpretation of support vector regression models. Anal. Chim. Acta. 595 (1), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2007.03.023 (2007).

Saravanan, A. et al. Thermal performance prediction of a solar air heater with a C-shape finned absorber plate using RF, LR and KNN models of machine learning. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progr. 38, 101630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2022.101630 (2023).

Loisel, J. et al. Machine learning for temperature prediction in food pallet along a cold chain: Comparison between synthetic and experimental training dataset. J. Food Eng. 335, 111156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2022.111156 (2022).

Comito, C. & Pizzuti, C. Artificial intelligence for forecasting and diagnosing COVID-19 pandemic: A focused review. Artif. Intell. Med. 128, 102286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2022.102286 (2022).

Gharaee, H., Erfanimatin, M. & Bahman, A. M. Machine learning development to predict the electrical efficiency of photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) collector systems. Energy. Conv. Manag. 315, 118808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118808 (2024).

Namdari, A. & Li, Z. A review of entropy measures for uncertainty quantification of stochastic processes. Adv. Mech. Eng. 11 (6), 1687814019857350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814019857350 (2019).

Funding

There is no external funding received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G. and X.H. developed the CFD model and conducted the numerical simulations. J.W. designed and implemented the machine learning models and performed the statistical and entropy analyses. Y.L. conceived the study, supervised the overall project, and provided guidance on the integration of CFD and machine learning methods. L.G. and J.W. wrote the main manuscript text. X.H. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 and the tables. X.H. was mainly responsible for the revision. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, X., Guo, L., Wang, J. et al. Computational fluid dynamics and machine learning integration for evaluating solar thermal collector efficiency -Based parameter analysis. Sci Rep 15, 24528 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10212-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10212-w