Abstract

The increasing complexity of wireless transmission environments and the growing demand for precise localization in non-line-of-sight (NLOS) scenarios present significant challenges for conventional localization methods. While reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS) offer a promising solution by creating virtual signal paths, existing RIS-assisted methods face critical challenges in high-frequency regimes where spatial aliasing occurs. This paper introduces a novel RIS-assisted localization system designed for high-frequency signal positioning under NLOS conditions. Our proposed approach addresses these challenges through a cost-effective system and proposes a spatio-temporal-frequency information fusion (STFIF) direct localization algorithm that effectively resolves spatial aliasing issues in high-frequency applications. The STFIF framework integrates three key components: (1) sparse signal reconstruction via semi-definite programming for spatial domain parameter estimation, (2)frequency difference processing to suppress spatial aliasing and artifact targets, and (3) temporal-domain information exploitation through RIS’s time-varying configurations. Comparative analysis with existing frequency difference-based techniques demonstrates the superior performance of our approach in both single and multiple snapshot scenarios, highlighting its robustness and practical applicability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The demand for precise localization is escalating with the rapid advancement of wireless systems. Traditional localization methods often struggle in complex urban and indoor environments due to their reliance on line-of-sight (LOS) propagation paths. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS) offer a promising solution by creating controllable reflective paths to enable effective localization in non-line-of-sight (NLOS) scenarios. Furthermore, RIS present a cost-effective and energy-efficient alternative to deploying additional anchors or relays1as a single receive antenna can estimate the target location with the RIS assistance2,3. Moreover, RIS feature a simplified hardware design, which facilitates easier deployment and maintenance4.

Research has underscored the potential of RIS to enhance wireless positioning accuracy. Theoretical analyses using the Cramér-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) established fundamental limits of localization accuracy under varying RIS configurations5with Wymeersch et al.3 demonstrating a reduction in positioning error compared to passive scattering approaches. Investigations revealed that localization error generally decreases as RIS aperture size grows, and distributed RIS deployments can simultaneously lower the CRLB and extend coverage6. In RIS-assisted localization, the target’s position is determined using anchor nodes with known coordinates by extracting parameters such as Time of Arrival (ToA), Angle of Arrival (AoA), and Angle of Departure (AoD)7,8,9,10. These approaches fall into two categories: model-based methods utilizing mathematical models and signal processing while maintaining robustness11,12and data-driven methods employing machine learning but potentially suffering performance degradation outside training conditions. Various model-based implementations demonstrate practical capabilities, including Keykhosravi et al.10 introducing a low-complexity estimator combining ToA and AoD, Fascista et al.13 developing a Maximum Likelihood-based AoA method, and Zhou et al.14 deploying two aerial RISs with a discrete Fourier transform-based positioning framework. Recent advances include a single-antenna full-duplex system achieving centimeter-level accuracy in indoor scenarios15 and Zhang et al.16 pioneering sub-RIS beam steering-assisted localization with environment-aware probabilistic modeling.

In RIS-assisted localization systems, the element spacing is typically designed as half the wavelength of the incident signal17. However, in practical scenarios, the wavelength of the target signal is often unknown. As the signal frequency increases, spatial aliasing occurs18. To mitigate this issue, difference frequency (DF) technology has been widely adopted as an effective solution. suppressing grating lobes through signal down-conversion while maintaining localization accuracy19,20. DF-based methods have demonstrated robust performance, achieving meter-level source positioning via measured-to-simulated wavefield correlation20,21 and enabling high-frequency DOA estimation comparable to low-frequency conventional beamforming (CBF)21. Further improvements integrate DF with deconvolution to refine CBF’s angular resolution20. Additionally, DF-based matched field processing enhances target localization by correlating received signals with model-simulated wavefields generated through acoustic propagation modeling22,23. A DF-integrated Multiple Signal Classification (MUSIC) technique has been developed to address spatial aliasing and suppress spurious DOA components in high-frequency DOA estimation. By analyzing three distinct DF combination strategies — time, frequency, and hybrid time-frequency processing — the method effectively resolves spatial aliasing while suppressing artifact DoA24. The aforementioned algorithms are primarily designed for LOS environments and often simplify location parameters during modeling. This simplification can lead to incomplete data at the receiver, ultimately degrading localization accuracy. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no investigation of RIS-assisted localization systems operating under conditions that involve spatial aliasing at high frequencies.

In this paper, we present a RIS-based localization system designed to pinpoint high-frequency signals under NLOS propagation. By fully exploiting multi-domain information, the proposed algorithm effectively resolves spatial aliasing and achieves robust localization. The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

We proposed a cost-effective localization system that operates robustly under NLOS condition. Unlike conventional systems rely on array antenna, the proposed architecture achieves accurate positioning using only a single-sensor receiver and a single RIS. This design eliminates the need for costly phased arrays or dense sensor deployments while maintaining functionality in obstructed environments.

-

(2)

We introduce a spatio-temporal-frequency information fusion (STFIF) direct localization algorithm to overcome challenges of high-frequency NLOS localization. The STFIF framework resolves these challenges through tri-domain fusion:1) Sparse signal reconstruction via semi-definite programming (SDP) for preliminary parameter estimation in the spatial domain, 2) DF processing to suppress spatial aliasing and artifacts targets, and 3) temporal-domain information derived from RIS’s time-varying configurations, fully leveraging multi-dimensional signal characteristics.

-

(3)

We perform a comparative analysis by integrating the DF-based techniques presented in prior literature into our proposed RIS-assisted direct localization framework. Moreover, we demonstrate the versatility and effectiveness of our proposed algorithm by validating its performance in scenarios with both single and multiple snapshot conditions. The numerical results indicate robust localization performance in both cases, highlighting the adaptability and practical feasibility of our proposed STFIF algorithm.

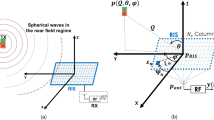

System models

The proposed localization system comprises a single receive sensor, a dynamically RIS in controlled motion, and two closely spaced target sources. The RIS performs Q signal reception cycles, where each cycle is partitioned into P non-overlapping segments. The RIS follows a linear motion with a constant velocity. During each signal reception cycle, the RIS is assumed to remain completely stationary at position \({{\mathbf{u}}_{\text{q}}}=[{u_{q,x}},{u_{q,y}}]\)\(\left( {q=1,2, \cdots ,Q} \right)\). This assumption is reasonable as the signal acquisition time at each position is typically short, and any micro-movements during data collection would be negligible. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the direct path from the targets to the receiver is obstructed, preventing LOS transmission. Consequently, the target signals are received exclusively through reflections from the RIS. The primary objective is to estimate the positions of the targets based on the signals recorded at the receiver. The RIS contains \({N_{ris}}\) programmable elements with an inter-element spacing of d. Consider K targets located at \({{\varvec{e}}_k}=\left[ {{e_{k,x}},{e_{k,y}}} \right]\), each transmitting signals at frequency f. The source signal vector is defined as \(\user2{S}_{f} \user2{ = }\left[ {s_{{t_{1} ,f}} ,s_{{t_{2} ,f}} , \cdots ,s_{{t_{L} ,f}} } \right] \in \mathbb{C}^{{K \times L}}\). The received signal matrix \({{\varvec{X}}_f}=\left[ {{x_{{t_1},f}},{x_{{t_1},f}}, \cdots ,{x_{{t_L},f}}} \right] \in {{\mathbb{C}}^{P \times L}}\) over Lsnapshots is given by

where \({\varvec{W}}\sim \mathcal{N}(0,{\sigma ^2}) \in {{\mathbb{C}}^{P \times L}}\) denotes white Gaussian noise. The time-varying measurement matrix \({{\mathbf{H}}_R} \in {{\mathbb{C}}^{P \times {N_{{\text{ris}}}}}}\) accounts for the dynamic reconfiguration of the RIS over time, incorporating P measurements across its \({N_{ris}}\) programmable elements. \({{\mathbf{A}}_r}=[{\mathbf{a}}({{\mathbf{e}}_0}),{\mathbf{a}}({{\mathbf{e}}_1}), \cdots ,{\mathbf{a}}({{\mathbf{e}}_{K - 1}})] \in {{\mathbb{C}}^{{N_{ris}} \times K}}\) denotes the steering matrix of RIS, and we have

c is the sound speed and \({{\text{d}}_n}\) represents the nth element spacing. \({\theta _k}\) is the AoA of the k-th target arriving at the RIS. The relationship of the target’s position and \({\theta _k}\) is described as follows:

STFIF direct localization algorithm

-

1.

Spatial sparse reconstruction.

To obtain the target location information, we leverage the signal’s sparsity through the ANM method. The resulting problem formulation is:

in this formulation, we define \({{\varvec{Y}}_f}={{\varvec{A}}_{\text{r}}}{{\varvec{S}}_f} \in {{\mathbb{C}}^{{N_{ris}} \times L}}\) to simplify the representation.\({\left\| {{{\varvec{Y}}_f}} \right\|_\mathcal{A}}\)denotes the atomic norm of \({{\varvec{Y}}_f}\), \(\rho\)is a regularization parameter that balances data fidelity with sparsity, typically set to \(\rho =\sqrt {{\sigma _{\text{w}}}N\log N}\). To solve the optimization problem in Eq. (5), we leverage the ANM technique, based on the approach described in reference25the atomic norm is given by:

\({\mathbf{u}} \in {{\mathbb{C}}^{{N_{ris}} \times 1}}\),\(\text{T}\text{o}\text{e}\text{p}({\mathbf{u}})\) is a Toeplitz matrix denoted as:

the ANM problem can be restated as follows:

we can recover the sparse signal \({{\varvec{Y}}_{{f}}}\) by employing an SDP-based approach, The parameter \(\rho\) usually set as \(\rho \approx \sigma \sqrt {{N_{ris}}\log {N_{ris}}}\). the Eq. (8) can be solved using the CVX convex optimization toolbox in MATLAB.

The formulation presented above applies generally to multiple snapshots. Under the single-snapshot scenario, the constant t replaces the matrix \(\varvec{\Upsilon}\)leading to a simplified form

-

2.

Difference frequency.

We leverage differential frequency to establish an equivalent array response with enhanced spatial resolution. This is achieved through the Hadamard product (\(\odot\)) between the upper-frequency data matrix \({{\varvec{Y}}_{{f_i}^{U}}}\) and the complex conjugate of corresponding lower-frequency components \({{\varvec{Y}}_{{f_i}^{L}}}\)24formulated as

To simplify the expression, let \({\varvec{a}}_{{\Delta {f_i}}}^{{}}({\varvec{e}})={\varvec{a}}_{{f_{i}^{U}}}^{{}}({\varvec{e}}) \odot {\varvec{a}}_{{f_{i}^{L}}}^{*}({\varvec{e}})\) .The cross-terms in Eq. (10) generate false responses values, resulting in \({K^2} - K\) artifact targets for K true targets, which degrade the localization accuracy. In the subsequent processing stages, mitigating the impact of artifact targets is critical. A fundamental characteristic of these artifact targets, generated by cross-terms, is that their apparent positions in the spatial spectrum are contingent upon the specific frequencies employed in the DF calculation. In contrast, the physical locations of true targets remain fixed, with their corresponding peaks in the spatial spectrum demonstrating consistency across various frequency processing methods. The STFIF algorithm exploits this frequency-dependent property of artifacts. Through fusion of multi-dimensional information derived from different frequencies, the algorithm effectively combines the spatial spectra.

-

(1)

DF-CBF.

The product \({{\varvec{Y}}_{\Delta {f_i}}}\) from Eq. (10) and \({\varvec{a}}_{{\Delta {f_i}}}^{{}}({\varvec{e}})\) are employed to carry out the conventional beamformer (CBF) .The DF sample covariance matrix (DF-SCM), denoted by \({R_{cbf}}\),is used for estimate unknow localization \(\hat {{\varvec{e}}}\). The resulting CBF power at each angle location is given by

The target location can be obtained by solving for the maximizer of Eq. (10).

-

(2)

Multi-information fusion.

Recall the Eq. (10), for a single vector \({y_{\Delta {f_i},l}}\)

the first, second, and third terms are uncorrelated. The covariance matrix can be formulated as

where \({\left[ {{{\varvec{R}}_x}} \right]_{i,j}}={\mathbb{E}}\left[ {{x_i}x_{j}^{*}} \right]\). The estimated covariance matrix can be obtained from

By performing eigenvalue decomposition of \({\varvec{R}}\), the signal subspace and noise subspace components can be obtained, written as:

Due to the presence of cross-terms, the eigen-decomposition yields \({K^2}\) largest eigenvalues corresponding to the signal subspace (which still contains noise components), while the remaining \({N_{{\text{ris}}}} - {K^2}\) eigenvalues constitute the noise subspace. These two subspaces are mutually orthogonal

The cost function can be formulated as:

The formulation discussed above is suitable for multi-snapshots. In the single-snapshot scenario, the covariance matrix cannot be computed directly from Eq. (16). Additional information is required to construct the covariance matrix. Here, we utilize frequency-domain components to form the covariance matrix instead

Performing eigenvalue decomposition on \({{\varvec{R}}_{ss}}\) yields the corresponding signal subspaces and noise subspaces \({\varvec{U}}_{N}^{{ss}}\). We formulate the cost function as:

To provide a more detailed exposition of the algorithm, the pseudocode for the STFIF algorithm is shown in Table 1.

To clearly illustrate the characteristics and advantages of the proposed STFIF algorithm relative to relevant baseline methods, we summarize their comparison across key technical dimensions in Table 2.

Simulation results

In this section, we conduct numerical simulations to validate the effectiveness of the proposed STFIF localization algorithm, particularly focusing on its performance in distinguishing two closely located targets. The simulated scenario involves two targets placed at \({{\varvec{e}}_1}=(50,100)m\),\({{\varvec{e}}_2}=(60,100)m\), with an intentionally minimal spatial separation of only\(10m\). The simulation environment is configured as follows: an RIS composed of \({N_{ris}}=32\)elements, employing a random coding scheme for its reflection matrix \({{\varvec{H}}_R}\), gather signal data over \(P=8\)time slots and observe \(L=50\) snapshot data. The element spacing of the RIS is normalized as\(d=c/2\Delta f\), and the frequency of the transmitted signal is set between 3.5 and 5 times the frequency \(\Delta f\). Here, we define uniformly spaced DF as \(\Delta f=f_{i}^{U} - f_{i}^{L}=10\text{k}\text{H}\text{z}\). To excute \(Q=5\)multiple measurements, the RIS initiates measurements from coordinate \({{\varvec{u}}_1}=(0,0)m\) and subsequently moves along the x-axis, performing additional measurements at intervals of \(15m\),such as \({{\varvec{u}}_2}=(15,0)m\),\({{\varvec{u}}_3}=(30,0)m\),\({{\varvec{u}}_4}=(45,0)m\), \({{\varvec{u}}_5}=(60,0)m\).

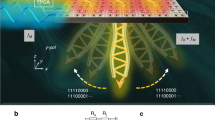

As shown in Fig. 2, the spatial spectra obtained using the proposed DF technology are presented for three frequency components (35 kHz, 42.5 kHz, and 50 kHz). The results demonstrate that while our DF approach successfully overcomes the spatial aliasing problem that commonly affects conventional beamforming methods, unwanted artifact targets still appear in the spectra. The two prominent central peaks highlighted by green circles correspond to the true target positions, whereas the additional peaks marked by red arrows represent artifact targets that could lead to false detections. These artifact targets exhibit clear frequency-dependent characteristics—notably shifting their positions in the spatial domain as the operating frequency changes from 35 kHz to 50 kHz. By applying our proposed algorithm, as demonstrated in Fig. 3, the 3D plot shows successful suppression of artifact targets, leaving only the two true targets clearly visible. The algorithm achieves enhanced target localization by exploiting the frequency-dependent characteristics of artifact peaks while preserving the consistent spatial signatures of genuine targets.

Spatial spectrum obtained using DF technology at three different frequencies (35 kHz, 42.5 kHz, and 50 kHz). The 3D plots illustrate the spectral power distribution across the x-y coordinate plane, where peaks indicate potential target locations. True targets are highlighted with green circles, while artifact targets (false positives) are marked with red arrows.

We compare our proposed method STFIF with DF-CBF and DF-MUSIC. Additionally, the performance of STFIF in the single-snapshot scenario is also compared, highlighting its effectiveness under conditions with limited snapshot availability. We use the root mean square error (RMSE) to measure the localization performance. The CRLB25 is also included in our comparisons as a theoretical performance benchmark, representing the minimum variance that can be achieved by any unbiased estimator. All simulations were performed over 500 Monte Carlo trials, the RMSE is computed using the standard formula:

where \(monte\) represents the total number of Monte Carlo trials and \({\hat {{\varvec{e}}}_k}\) is the estimated position.

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of the RMSE performance for various algorithms across different noise levels, with the SNR ranging from 5 dB to 20 dB. It is evident that the proposed STFIF algorithm consistently outperforms DF-CBF and DF-MUSIC, exhibiting notably lower RMSE values at identical SNR conditions. Although all evaluated methods demonstrate improvements as the SNR increases, the STFIF method achieves superior estimation accuracy closer to the CRLB than other comparative algorithms. The gap between STFIF and the CRLB indicates potential for further algorithmic refinement, while clearly highlighting STFIF’s robustness and enhanced ability to handle noise in comparison to alternative approaches.

Figure 5 analyzes the impact of the number of RIS elements on localization performance, with the SNR fixed at 10 dB and the number of RIS elements varying from 15 to 40. The simulation results demonstrate a clear trend: as the number of RIS elements increases, the RMSE of all algorithms decreases, with our proposed STFIF algorithm consistently achieving the lowest error. Notably, the STFIF method maintains superior performance across the entire range compared to DF-CBF, DF-MUSIC, and STFIF-single approaches, with its error curve closest to the theoretical CRLB limit. This performance advantage becomes more pronounced with larger RIS arrays, where STFIF achieves approximately 0.13 m RMSE at 40 RIS elements, significantly outperforming conventional methods. The decreasing gap between STFIF and CRLB with increasing RIS elements suggests that our proposed algorithm can more effectively leverage the additional spatial diversity provided by larger RIS arrays, making it particularly well-suited for high-precision localization applications that employ substantial reconfigurable surfaces.

Beyond localization accuracy, computational complexity serves as another critical metric for evaluating the practical feasibility of localization algorithms. The computational complexity of these algorithms is primarily determined by several key operations: the computation of the covariance matrix from received signals, eigen decomposition of this matrix, and the evaluation of a spatial spectrum over a grid of possible angles. While the complexity of covariance matrix computation and eigen decomposition remains consistent across all three algorithms, the spatial spectrum search dominates the overall computational cost. The proposed STFIF algorithm incurs a marginally higher complexity in this step due to additional processing requirements, yet demonstrates only negligible computational overhead compared to DF-CBF and DF-MUSIC. The detailed quantitative comparison is presented in Table 3, where \({N_{grid}}\) denotes the number of grid points in the spatial search.

Conclusions

This study investigates RIS-assisted high-frequency localization and addresses the issue of spatial aliasing that arises in conventional array architectures. To overcome this challenge, we propose a STFIF algorithm, which integrates three critical components: (1) Sparse signal reconstruction via SDP for initial parameter estimation, (2) DF processing to mitigate spatial aliasing and artifact targets, and (3) integration of RIS’s time-varying configurations, multi spatial-domain measurements, and the accumulation of multi-frequency components. By effectively exploiting multi-dimensional information, the proposed STFIF algorithm achieves superior positioning performance with enhanced resolution and accuracy.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are fully contained within this published article.

References

Jian, M. et al. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces for wireless communications: overview of hardware designs, channel models, and Estimation techniques. Intell. Converged Netw. 3, 1–32 (2022).

Keykhosravi, K. et al. Leveraging RIS-Enabled smart signal propagation for solving infeasible localization problems: scenarios, key research directions, and open challenges. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 18, 20–28 (2023).

Wymeersch, H. & Denis, B. Beyond 5G Wireless Localization with Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces. in ICC 2020–2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC) 1–6IEEE, Dublin, Ireland, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC40277.2020.9148744

Renzo, M. D. et al. Smart radio environments empowered by reconfigurable AI meta-surfaces: an idea whose time has come. J Wireless Com Network 129 (2019). (2019).

Hu, S., Rusek, F., Edfors, O. & Beyond Massive, M. I. M. O. The potential of positioning with large intelligent surfaces. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 66, 1761–1774 (2018).

Hu, S., Rusek, F. & Edfors, O. Cramér-Rao lower bounds for positioning with large Intelligent surfaces. in IEEE 86th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC-Fall) 1–6 (IEEE, Toronto, ON, 2017). 1–6 (IEEE, Toronto, ON, 2017). (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/VTCFall.2017.8288263

Zhao, Y., Chen, P., Sun, M., Luo, T. & Cao, Z. RIS-Aided sensing system with localization function: fundamental and practical design. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 506–514 (2024).

Emenonye, D. R., Dhillon, H. S. & Buehrer, R. M. Fundamentals of RIS-Aided localization in the Far-Field. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2023.3307818 (2023).

Wu, Z. et al. Multiple anchors and RIS-Aided localization method in complex NLOS environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3433948 (2024).

Keykhosravi, K., Keskin, M. F., Seco-Granados, G. & Wymeersch, H. SISO RIS-Enabled Joint 3D Downlink Localization and Synchronization. in ICC - IEEE International Conference on Communications 1–6 (IEEE, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021).https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC42927.2021.9500281

Shah, S. T. et al. Coded environments: data-driven indoor localisation with reconfigurable intelligent surfaces. Commun. Eng. 3, 66 (2024).

Faisal, K. M. & Choi, W. Machine learning approaches for reconfigurable intelligent surfaces: A survey. IEEE Access. 10, 27343–27367 (2022).

Fascista, A., Keskin, M. F., Coluccia, A., Wymeersch, H. & Seco-Granados, G. RIS-Aided joint localization and synchronization with a Single-Antenna receiver: beamforming design and Low-Complexity Estimation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal. Process. 16, 1141–1156 (2022).

Zhou, T. et al. AoA-Based positioning for aerial intelligent reflecting Surface-Aided wireless communications: an angle-Domain approach. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 11, 761–765 (2022).

Ye, Z., Junaid, F., Ibrahim, E., Nilsson, R. & Van De Beek J. Monostatic sensing for passive RIS localization and tracking. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 13, 1260–1264 (2024).

Zhang, J., Wu, J. & Wang, R. User localization and environment mapping with the assistance of RIS. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 73, 8549–8562 (2024).

Dmochowski, J., Benesty, J. & Affes, S. On Spatial aliasing in microphone arrays. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 57, 1383–1395 (2009).

Yang, L., Wang, Y. & Yang, Y. Aliasing-free broadband direction of arrival Estimation using a frequency-difference technique. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 150, 4256–4267 (2021).

Gao, W., Zhu, S., Li, X., Wang, H. & Wang, L. Frequency-difference MUSIC: a method for DOA Estimation in inhomogeneous media. SIViP 18, 7029–7040 (2024).

Xie, L., Sun, C. & Tian, J. Deconvolved frequency-difference beamforming for a linear array. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 148, EL440–EL446 (2020).

Douglass, A. S., Song, H. C. & Dowling, D. R. Performance comparisons of frequency-difference and conventional beamforming. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 142, 1663–1673 (2017).

Worthmann, B. M., Song, H. C. & Dowling, D. R. Adaptive frequency-difference matched field processing for high frequency source localization in a noisy shallow ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 141, 543–556 (2017).

Worthmann, B. M., Song, H. C. & Dowling, D. R. High frequency source localization in a shallow ocean sound channel using frequency difference matched field processing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 138, 3549–3562 (2015).

Park, Y., Gerstoft, P. & Lee, J. H. Difference-Frequency MUSIC for DOAs. IEEE Signal. Process. Lett. 29, 2612–2616 (2022).

Li, J., Wang, J., Cui, W. & Jian, C. UAV-Mounted RIS-Aided Multi-Target localization system: an efficient Sparse-Reconstruction-Based approach. Drones 8, 694 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jingjing Li: Conceived the research idea, designed the methodology, and led the overall study. Contributed to manuscript writing and revisions.Jianhui Wang: Assisted in algorithm development and experimental implementation. Contributed to manuscript drafting and data analysis.Lihao Liu: Conducted simulations, analyzed results, and contributed to manuscript preparation.Weijia Cui: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, ensuring technical accuracy and clarity.Chunxiao Jian: Provided critical feedback on the methodology and contributed to manuscript revisions.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Wang, J., Liu, L. et al. RIS-assisted anti-spatial aliasing direct localization in NLOS scenarios via spatio-temporal-frequency information fusion. Sci Rep 15, 28146 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10257-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10257-x