Abstract

In this study, we addressed the influence of individual differences in personality traits measured trough a Big Five personality test, and sociodemographic variables such as age or gender, in the processing of words conveying discrete emotions. To this aim, we relied on data from a large-scale lexical decision task in Spanish. The analyses with linear mixed models revealed several interactions between emotional content and both personality traits and sociodemographic factors during word recognition. In this sense, there was a facilitation for fear-related words, mainly in male participants. Also, disgust interacted with agreeableness and conscientiousness, showing an inhibition for disgust-related words in participants scoring low in agreeableness or high in conscientiousness. Sadness-related words were processed more slowly in men, while this effect was absent in women. Finally, happiness-related words showed an interaction with openness to experience, age and gender. We discuss the complex interplay between the emotional connotation of words and individual differences. All in all, our findings emphasise the need to take individual characteristics into account when examining emotional word processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of how emotional content affects language processing has been extensively investigated in recent decades (see1,2, for reviews). Much of this research has focused on examining the emotional content of words from a dimensional approach, which defines it as a combination of two variables: valence and arousal3. Valence represents the hedonic value of the emotional content, a continuum ranging from highly unpleasant/negative to highly pleasant/positive. In contrast, arousal refers to the intensity of physiological and psychological alertness triggered by an emotion, ranging from highly relaxing to highly exciting. The most used task to study the effect of valence and arousal in word recognition is the Lexical Decision Task (LDT; e.g4), in which participants decide whether a string of letters is a real word or a nonword; response times (RTs) and errors are recorded. However, the evidence for the effects of these two variables in the LDT remains inconclusive. In particular, it is unclear whether high levels of valence facilitate (i.e., speed up) RTs regardless of their polarity (e.g5). , or whether positive valence (e.g., “gift”) facilitates recognition compared to neutral words (e.g., “chair”), while negative valence (e.g., “trash”) is inhibitory (i.e., it slows down RT, e.g6). In this regard, a recent meta-analysis4 shows a consistent effect of positive valence in word recognition, while the effect of negative valence is less clear.

Several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain how emotional valence influences word recognition. First, the model of motivated attention and affective states7 posits that both positive and negative stimuli signal survival-relevant approach or avoidance goals, thereby recruiting our motivational systems and receiving prioritised processing. Thus, emotional words should be processed faster than neutral ones. Second, the automatic vigilance hypothesis8 argues that negative stimuli - an evolutionary cue to threat - capture and hold attention more strongly, delaying attentional disengagement and slowing concurrent cognitive tasks such as word processing. Finally, theories of embodied semantics propose that affective experience is a core semantic dimension, especially for abstract words. Thus, extreme valence (either highly positive or highly negative) enriches multimodal representations and leads to faster word processing9,10.

The inconsistency in the effects of emotional valence poses a significant challenge to a full understanding of how the emotional content of words is processed and represented. For this reason, research in this field has focused, in part, on the factors that may be causing this discrepancy. At least three factors have been identified. The first of them is the lack of experimental control in previous studies (see11). For example, emotional words may differ from neutral words in variables such as frequency and concreteness, both of which interact with valence effects (e.g12,13). To address this limitation, recent research has used large-scale lexical decision tasks (i.e., mega-studies; see14). In these studies, data are collected from a large number of participants who respond in a LDT to many words characterised in a wide range of psycholinguistic variables. This approach ensures high statistical power while aiming for a high degree of experimental control (see14). The results of these mega-studies show a linear relationship between emotional valence and lexical decision times: Positive words are detected faster than neutral and negative words, while negative words are detected slower than neutral words (e.g6,15,16,17, but see9,18).

The second factor relates to the possibility that the dimensional approach may not be the most appropriate, or at least the only one, for characterising the emotional content of words. It has been suggested that a more accurate definition of the emotional content of a word should also consider the specific emotion it evokes19. This approach is based on discrete emotion models (e.g20), which postulate the existence of a limited number of discrete emotions (i.e., happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust) that manifest in specific and distinctive patterns of behaviour, cognition, and subjective experience (e.g21,22). Furthermore, each discrete emotion appears to depend on the activity of specific neural pathways (e.g23).

The main evidence in support of discrete emotion models comes from the study of emotional facial expressions (e.g24,25). However, the impact of discrete emotions on word processing has been scarcely investigated, with only a limited number of published studies to date. This might be a crucial point regarding the disparity of effects observed for negative valence. Since there are several discrete negative emotions (sadness, fear, disgust, anger) that might be associated with the activity of different motivational systems (withdrawn vs. approach), their effects in word recognition may not go in the same direction (e.g., inhibition vs. facilitation). The likely uneven distribution of these discrete emotions in previous studies may therefore have contributed to the different experimental results. This is clearly exemplified by the fact that words with similar levels of valence and arousal, like “nightmare” (valence = 1.8, arousal = 7.6) and “nausea” (valence = 1.8, arousal = 6.65), can be related to different discrete emotions (in this case, fear and disgust, respectively).

One of the earliest studies in this area was conducted by Briesemeister et al.26, who found that the recognition of words related to happiness and fear was faster compared to neutral words, while the recognition of words related to disgust was inhibited. Notably, this study found that when discrete emotion variables and dimensional variables were included as predictors of recognition times, only the former yielded a significant effect. Other LDT studies have reported an inhibitory effect of both disgust- and fear-related words, with no significant differences between the two27. Also, a similar inhibitory effect of both anger and fear-related words has been observed28.

Neurophysiological data further supports the influence of discrete emotions on word processing. Briesemeister et al.29 investigated the temporality of the effects of discrete and dimensional emotion variables using electroencephalography (EEG) measures. They orthogonally manipulated happiness (high and low) and valence (neutral or positive) and observed earlier EEG effects for happiness than for valence, and no interaction between the two variables. Moreover, a gamma power band synchronization for fear words relative to anger words have been reported30. These findings appear to be consistent with the hierarchical emotion theory22, which suggests that both discrete and dimensional emotion variables belong to the same emotional processing system, but influence different processing stages.

The third factor which may have contributed to the inconsistency in the effects of emotional valence in word recognition is the role of individual differences in the processing and representation of emotional words. The way that people perceive the emotional content of a word can be influenced by various individual characteristics, such as personality traits, age and gender. For example, the emotion evoked by a word such as “party” may differ significantly between individuals with different levels of extroversion; for extroverts it may be associated with positive emotional content, whereas for introverts it may evoke negative or neutral emotions. Other examples include the word “freedom”, which may have different emotional connotations depending on a person’s age. For instance, younger adults may experience this word as more emotionally arousing or positively valenced, potentially associating it with aspirations and autonomy, whereas older adults may link it to past experiences or losses, resulting in different emotional appraisals. In this line, recent research has shown that arousal ratings for emotionally charged words tend to decline with age, and that the relationship between arousal and other emotional dimensions—such as tabooness or humor—weakens across the lifespan31. This suggests that aging is associated with reduced emotional reactivity to certain types of language, which may modulate the emotional weight that words like “freedom” carry. Similarly, the word “cry” may evoke different emotional responses in men and women. Women tend to cry more frequently and intensely than men (e.g32. These disparities are influenced by both biological factors, such as hormonal differences, and social norms that discourage emotional expression in men33. Consequently, the word “cry” may carry different emotional connotations across genders, reflecting these underlying differences in emotional expression and regulation.

In a recent study15, we investigated the role of individual differences in emotional word recognition by examining the interaction between valence and arousal with age, gender and personality traits (Big Five): extraversion (social interaction and energy levels; ranging from introverted to extraverted), openness to experience (creativity and curiosity for new experiences; ranging from conservative to innovative), agreeableness (empathy and cooperation; from confrontational to cooperative), emotional stability (stress management; from neurotic to emotionally stable), and conscientiousness (organization and dependability; from impulsive to disciplined) (see also34,35). Overall, we found a linear effect of valence, with a facilitation for positive words and an inhibition for negative ones. Our results also revealed several significant interactions. We found an interaction between valence and extraversion: The recognition of positive words was facilitated in extroverted participants, but not in participants with medium or low levels of extraversion. In addition, an interaction between conscientiousness and valence was observed, showing that the effect of valence was not significant for participants with low levels of conscientiousness, but became significant and larger as conscientiousness increased. The opposite pattern was found for valence and openness to experience. In addition, the effect of valence decreased or even disappeared as a function of age, and women showed a stronger valence effect than men, largely due to a lack of facilitation in the recognition of positive words among male participants. Considering the above, it is plausible that individual differences have contributed to the variability in findings related to emotional valence in previous research. The composition of the sample in these studies (e.g., a high proportion of extraverts or a greater presence of women) could have influenced the presence, magnitude, and direction of valence effects.

The impact of individual differences in emotional word processing offers a novel perspective on how emotional content is processed and represented. These findings suggest that there is no universal, one-size-fits-all explanation for the effect of emotional content. Instead, a full understanding of emotional effects in word processing requires taking into account the individual characteristics of speakers. For example, the observation that extroverts show a greater facilitation for positive words than introverts has been linked to the fact that extroverts tend to accumulate a greater number of positive life experiences than introverts34. Other findings have been interpreted in terms of the automatic vigilance hypothesis8, which suggests that humans have an innate predisposition to prioritise negative stimuli as a result of evolution, leading to negative words attracting more attention and delaying response times in the LDT36. In this sense, the increased valence effect observed in high-conscientiousness participants may be due to a greater attentional capture of negative words by such individuals, possibly because of their reduced use of such words37. On the other hand, the interaction between valence and openness to experience has been related to the greater emotional regulation observed in participants with higher scores on this factor38.

In the present study, we aim to extend our previous work15 by testing whether individual differences also influence the processing of words related to discrete emotions. This aspect has been scarcely explored, but there is some promising evidence from studies that employed the LDT. For example, Armstrong et al.39 found that participants with high sensitivity to contamination showed greater inhibition in the recognition of fear- and disgust-related words than to happiness-related words, compared to individuals with low sensitivity. In a further study, Mueller and Kuchinke40 reported that participants with high Behavioural Activation System (BAS41) scores, which indicate a greater predisposition to initiate approach behaviours, showed more inhibition in the recognition of fear-related words in a LDT. Specifically, the effect was observed in those with higher scores on the BAS-drive subscale, which measures persistent goal pursuit. According to the authors, individuals with high levels of goal-orientation would allocate more attentional resources to stimulus processing, thus increasing the inhibitory effect of fear-related words. In another study by Parrott et al.42, participants with high anger sensitivity responded faster to anger-related words than individuals with low anger sensitivity. Finally, Silva et al.43 tested participants with different levels of disgust sensitivity (low vs. high) in a LDT. Their results revealed an inhibition in the recognition of disgust-related words in individuals with high disgust sensitivity, while individuals with low disgust sensitivity showed the opposite effect. It is important to note, however, that none of these studies have examined the moderating effects of personality factors (i.e., Big Five), age, or gender on the processing of words related to discrete emotions.

In this study, we examine the impact of discrete emotions and individual differences in emotional word processing. To do that, we rely on data from our recent large-scale LDT mega-study15, which allows us to control for many extraneous variables and ensures robust statistical power. Through this approach, we aim to provide deeper insights into the complex influence of emotional content on lexical processing.

Method

The analyses carried out in this study rely on response times and measures of individual differences obtained from Haro et al.15. These authors collected lexical decision times for 7500 words from 918 native Spanish speakers (mean age = 27.51, range = 17–70, SD = 11.05; 69.83% female). In addition, the values of several psycholinguistic variables were included in the analyses, namely emotional valence and arousal, concreteness, familiarity, age of acquisition, logarithm of frequency, number of letters, number of syllables, number of phonemes, number of lexical neighbours, number of higher frequency lexical neighbours, number of phonological neighbours, number of higher frequency phonological neighbours, average orthographic Levenshtein distance to the 20 closest neighbors (OLD20), average bigram frequency and average trigram frequency. The sources for these values were the same as in Haro et al.15. Values for emotional valence and arousal were taken from previous normative studies44,45,46,47. The values for familiarity and concreteness were obtained from previous normative studies15,44,45,48,49. The values for age of acquisition came from previous normative studies15,48,50. The values for the lexical and phonological variables were retrieved from ESPAL49. In addition, we obtained the values of the discrete emotions (happiness, fear, anger, disgust and sadness) of all 7500 words from different databases46,51,52) (see Table 1 for the statistics descriptives of these values; see15, for the statistics descriptives of the rest of variables). It is worth noting that although the values were obtained from several studies, the population from which the samples were taken in each of these studies was comparable, i.e. mainly young women studying at one of the Spanish universities. Furthermore, most of these studies assessed the validity of the measures collected by comparing them with other studies published in Spanish, showing in most cases high correlations between them (see, for example45).

Data analyses

We followed the same data cleaning procedure of RTs as in Haro et al.15. In particular, we excluded participants with error rates above 15% (n = 59) and words with error rates over 75% (n = 5). This left 7,495 words, each averaging 36.72 observations (range: 31–43, SD = 2.66). Observations with RTs below 300 ms or below or above 2.5 standard deviations from each participant’s mean were discarded. Overall accuracy was high (94.73%), so errors were not analyzed. In total, we removed 50,360 observations (8.59%), resulting in 506,848 observations for analysis. We analyzed the data using linear mixed effects models (e.g53,54), with the lme4 package in R55,56. The model was created to analyze the main effects and interactions of the variables of interest on raw RTs. We chose to analyze raw RTs to preserve interpretability and avoid potential artifacts introduced by data transformations, as highlighted by Lo and Andrews57. In addition, although raw RTs are often skewed, linear mixed-effects models are generally robust to such deviations, especially with large datasets. Discrete emotion variables (happiness, fear, anger, disgust, sadness) and their interactions with personality trait scores (extroversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, emotional stability, and conscientiousness), along with age and gender, were included as fixed effects. While higher-order interactions (e.g. three- or four-way combinations) could theoretically provide a more detailed understanding of how discrete emotions interact with individual differences, attempts to incorporate them into current models resulted in convergence issues. Additionally, we incorporated the remaining variables as covariates. Arousal and valence were introduced individually, as well as their interaction. All covariates were centred and transformed into z-scores. Random intercepts were specified for both participants and words; random slopes could not be included due to convergence issues. We checked for multicollinearity among the fixed effects (using the R VIF function) and excluded variables with a VIF > 5 or with a correlation > 0.80 with other fixed effects. Specifically, we removed number of phonemes, number of phonological neighbors, number of higher frequency phonological neighbors, and number of syllables. Participant gender was coded using sum contrast coding: female (−0.5), male (+ 0.5).

Multiple comparisons were performed using the emmeans software package58. For continuous variables, marginal means were calculated at two standard deviations below (referred to as ‘low level’) and above (referred to as ‘high level’) the mean, as well as at the mean itself (referred to as ‘medium level’). These levels were used for multiple comparisons of continuous variables and for visualizing the interactive effects when at least one continuous variable was involved. The Tukey method was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. Additionally, we report the results of t-test analyses on the coefficient estimates for each fixed effect and interaction. Satterthwaite’s approximation to the degrees of freedom of the denominator was used for this analysis (p-values were calculated using the lmerTest package59.

Results

The linear mixed effects model results revealed several interactions and main effects (see Table 2). These are detailed below, along with the results of multiple comparisons where relevant. Only significant main effects and interactions will be presented.

Valence and arousal effects

A significant effect of valence was found, β = −5.39, SE = 1.44, t = −3.74, p < .001 (Fig. 1). This effect indicates that as valence increases, RT decreases. Thus, there was a facilitative effect for positive words and an inhibitory effect for negative words. On the other hand, the effect of arousal was marginally significant, suggesting that words with high arousal values were recognized faster than those with low arousal values, β = −1.34, SE = 0.74, t = −1.82, p = .069.

Importantly, the effects of valence and arousal were moderated by their interaction, β = 1.92, SE = 0.52, t = 3.69, p < .001 (Fig. 2). Arousal influenced negative and positive words differently. A facilitative effect of arousal was observed for negative words: high-arousal negative words were recognized faster than low-arousal negative words (p < .001). Conversely, the opposite effect was found for positive words, indicating an inhibition for high-arousal positive words relative to low-arousal positive words (p = .018).

Fear

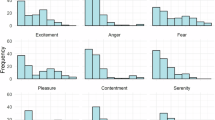

A facilitating effect of fear was observed, β = −2.55, SE = 0.98, t = −2.60, p = .009, showing that as fear increased, RT decreased (Fig. 3). There was also an interaction between fear and participant gender, β = −3.78, SE = 1.06, t = −3.58, p < .001. The effect of fear was significant for males (p < .001), but not for females (p = .791) (Fig. 4).

Disgust

There were several significant interactions between disgust and personality traits. Disgust interacted with agreeableness, β = −1.14, SE = 0.45, t = −2.56, p = .011 (Fig. 5). An inhibitory effect of disgust was observed for low agreeableness participants (p = .044), but was not significant for medium and high agreeableness participants (both ps > 0.29). Furthermore, an interaction was found between disgust and conscientiousness, β = 1.27, SE = 0.45, t = 2.79, p = .005 (Fig. 6). An inhibitory effect of disgust was observed for high conscientiousness participants (p = .032), but was not significant for medium and low conscientiousness participants (both ps > 0.19). Finally, disgust interacted with openness to experience, β = −0.86, SE = 0.42, t = −2.02, p = .043 (Fig. 7). The interaction was due to disgust showing an inhibitory trend at low openness to experience, but a clear null effect at medium openness to experience and a trend towards facilitation at high openness to experience.

Sadness

An interaction was found between sadness and participant gender, β = 5.64, SE = 1.16, t = 4.87, p < .001 (Fig. 8). There was an inhibitory effect of sadness for males (p = .002), but not for females (p = .438).

Happiness

Several interactions were found for happiness. There was an interaction between happiness and openness to experience, β = −0.86, SE = 0.42, t = −2.02, p = .043 (Fig. 9). The interaction was driven by a trend towards facilitation of happiness for low openness to experience participants, but a null effect for medium openness to experience and a trend towards inhibition for high openness to experience. There was also an interaction between happiness and participant age, β = 0.84, SE = 0.35, t = 2.39, p = .017 (Fig. 10). The interaction suggests a trend towards facilitation of happiness for younger participants, but a null effect for middle-aged participants and a trend towards inhibition for older participants. A further interaction was found between happiness and participant gender, β = 3.46, SE = 0.77, t = 4.50, p < .001 (Fig. 11). There was an inhibitory tendency of happiness for males, but a facilitatory tendency for females.

Discussion

In the present study we examined the influence of discrete emotions and individual differences on word recognition. We analysed lexical decision times from a recently published mega-study15, where response times to 7500 Spanish words were collected from 917 participants.

The results showed that the effect of emotional valence persisted even after controlling for the potential influence of discrete emotions. The valence effect is consistent with the findings of Haro et al.15 and other mega-studies of lexical decision with emotional words6,17, although these studies did not control for the effect of discrete emotions. We observed an inhibition in the recognition of negative words and a facilitation in the recognition of positive words. The inhibition of negative words is in line with the automatic vigilance hypothesis8, which suggests that negative words capture attention strongly and thus interfere with any other cognitive process taking place simultaneously. As a result, the processing of negative words is delayed. The recognition advantage seen with positive words is likely due to a different underlying mechanism. This facilitation is often attributed to the positivity bias in language, where positive words are used more frequently than negative or neutral words (e.g60). As a result of their higher frequency, positive words may have a lower identification threshold, requiring less activation for recognition17. However, in the present study, word frequency was controlled for. Therefore, frequency differences cannot account for the observed facilitation in recognition of positive words. Instead, this advantage may be attributed to other factors. A possible explanation is that positive words are generally more connected and elaborated61, associated with richer sensory experiences, and tend to have more meanings62 than neutral or negative words. This increased semantic richness may increase recognition speed for positive words through semantic-orthographic feedback processes (e.g63).

The results also showed an interaction between valence and arousal. Arousal speeded up recognition of negative words, but slowed down recognition of positive words. This complex relationship between arousal and valence has been observed in several studies (e.g15,64,65,66,67). and supports the model proposed by Robinson et al68. According to this model, negative valence and high arousal are associated with avoidance behaviour, often signaling a threat. Conversely, positive valence and low arousal are associated with non-threatening or attractive scenarios, leading to approach behaviour. As a result, different combinations of valence and arousal can produce either congruent (positive valence-low arousal, negative valence-high arousal) or incongruent (positive valence-high arousal, negative valence-low arousal) responses that can either facilitate or inhibit word recognition.

Importantly, in this study we also observed an effect of discrete emotions, suggesting that dimensional variables alone do not fully explain the influence of emotional content on word recognition. We found that, among the discrete emotions, only fear had a significant main effect on RTs. This finding is in line with the results of Briesemeister et al26. Notably, the effect was facilitatory, rather than the inhibitory effect more typically seen with negative valence, making it difficult to reconcile with the automatic vigilance hypothesis8. One possible explanation is that fear-related words have richer semantic representations than other negative words, which may give them a processing advantage (e.g63). Alternatively, this effect could be related to behavioural strategies associated with fear, consistent with the approach-withdrawal dimensions28. Thus, speeded recognition of words communicating fear might be of help to promote action tendencies to cope with threatening stimuli. In any case, further research is needed to clarify the source of this facilitatory effect of fear.

The effect found for fear-related words may also shed light on the mixed findings on negative valence in previous studies (see meta-analysis by Ferré et al.4). It is possible that the proportion of fear-related words within the negative valence condition varied across these studies, potentially acting as a confounding factor. Furthermore, this facilitatory effect of fear contrasts with previous findings27,28, which reported an inhibitory effect of fear. Although we cannot provide a definitive explanation for these discrepancies, it is important to note that, while the number and type of controlled variables in these studies were comparable to those in the present study, there were notable differences in the number of participants and stimuli per condition. Specifically, Ferré et al.27 included 36 words per condition with 42 (Experiment 1) to 56 (Experiment 2) participants, and Huete-Pérez et al.28 used 31 words per condition with 51 participants (Experiment 1). In contrast, our study employed a larger sample size and a greater number of stimuli, which likely enhanced the statistical power and reliability of our findings. In addition, unlike the present work, these studies used a factorial design. This is consistent with an observation by Briesemeister et al.26, who found a facilitatory effect of fear when they examined RTs from the English Lexicon Project (Experiment 1;69), but no effect in a factorial design (Experiment 3). The reason of the discrepant findings may be that mega-studies involve more words and participants than studies that use factorial designs, resulting in higher statistical power, and usually control for more variables. Thus, it is plausible that the differences between our findings and those of previous studies may be due to methodological differences. Regarding the other discrete emotions, our results are at odds with several studies that reported a main effect for disgust and happiness26,27. Although we did not observe a main effect for these emotions in the present study, we did find interactions between them and some individual differences (discussed later). Hence, these discrepancies may be related to the specific characteristics of the participants involved in these studies.

As mentioned above, the main contribution of this study was to examine how individual differences influence the processing of words related to discrete emotions. The results revealed several significant interactions, which we will now discuss in detail. Overall, these findings support the ‘contextual learning hypothesis’70. This hypothesis suggests that the individual’s lifetime experiences with basic emotions (such as happiness, fear, sadness, anger, and disgust) shapes people’s perception emotional content.

First, while fear had a general facilitating effect on RTs, this effect was only observed in men. The interaction between fear and gender suggests that women may not be affected by fear-related emotional content in word recognition. Given that the facilitating effect of fear is difficult to reconcile with the automatic vigilance hypothesis8 , these gender differences may be explained by other factors, possibly related to distinct behavioural strategies for dealing with fear stimuli between men and women. For example, the higher impulsivity typically observed in men compared to women71. It has been argued that this may be related to the heightened attraction of men to risk-taking behaviour (see metanalysis in Byrnes et al.72), which contrasts with the anxiety and caution that such risks typically evoke in women. This difference suggests that fear in men may act not as a barrier, but as a signal that a stimulus offers a potential reward. Consequently, rather than provoking an aversive or avoidance response, fear may actually trigger an approach or engagement response in men.

The interactions we found between disgust and several personality traits suggest that the inhibition effect observed for disgust-related words in previous studies26,27 might be modulated by participant characteristics. Specifically, we found an inhibition effect for disgust-related words in participants with low agreeableness, high conscientiousness, and also (although only as a trend) in those with low openness to experience. These interactions generally suggest that such individuals are more sensitive to disgust, in line with Silva et al.43 findings. For example, agreeableness has been shown to be negatively correlated with disgust sensitivity (e.g73); in other words, the lower the agreeableness, the greater the sensitivity to disgust. Highly agreeable individuals tend to exert more effort to control negative emotions when interacting with others and may have a higher threshold for feeling disgust towards others74,75. Furthermore, agreeableness leads individuals to prioritise the benefits of harmonious social interactions, resulting in reduced disgust towards human pathogens73. Complete avoidance of all contact, direct or indirect, would eliminate vital social behaviours, such as food sharing, mating, cooperative work and kinship care. No avoidance at all would leave you highly vulnerable to infection. Instead, the behavioural immune system dynamically calibrates avoidance in a context sensitive manner, trading off motivations to avoid disease against the benefits of social interaction, and moderating disgust with pathogens when interpersonal values are high76. There is also evidence of increased sensitivity to disgust in high conscientiousness individuals, which has been related to their traits of competence, orderliness, obedience, achievement, self-discipline, and deliberation77. Finally, the increased sensitivity to disgust in individuals with low openness to experience is consistent with some previous studies (e.g77,78), that have documented a negative relationship between the pursuit of new experiences and sensitivity to disgust. These findings suggest that individuals with high disgust sensitivity tend to have a less active imagination, less aesthetic sensitivity, less attention to inner feelings, less preference for variety, less intellectual curiosity, and less independence of judgement than those with low disgust sensitivity. They are less adventurous and more socially and politically conservative.

We also found an interaction between sadness and gender. Sadness-related words showed an inhibitory effect in men, but not in women. This finding may be linked to evidence suggesting that women report experiencing sadness more frequently than men (e.g79). In addition, there is evidence that women tend to use a higher proportion of sadness-related words than men80. This increased use of sadness-related words may stem from socialization practices where parents use more emotionally expressive language with daughters than with sons. For instance, Aznar and Tenenbaum81 observed that mothers are more likely to use emotional words when interacting with their 4-year-old daughters compared to mothers of 4-year-old sons. Furthermore, studies have shown that women often exhibit higher levels of empathy than men, which could contribute to a greater sensitivity and responsiveness to sadness-related stimuli. Christov-Moore et al.82 reported that women demonstrate greater empathic responses, both behaviorally and neurologically, compared to men. This heightened empathic concern may enhance the processing and recognition of sadness-related words among women. As a result, sadness-related words may be less familiar for men, making lexical access of these words more difficult and effortful. Additionally, in line with the automatic vigilance hypothesis8, given that these emotional words take longer to retrieve in men and are more salient because they are less frequent, their attentional capture would be more intense and prolonged, reflected in higher inhibition in LDT.

Finally, our study revealed several interactions between happiness and individual differences. For female and younger participants, we observed a facilitation trend for happiness-related words, consistent with previous findings (e.g26). Conversely, male and older participants showed an inhibition trend for these words. These findings are consistent with previous studies that observed interactions between age, gender, and valence15,83,84. Specifically, these studies found that the facilitation effect of positive valence was either exclusive to, or more pronounced in, women and younger individuals. Regarding the interaction with age, one possibility derived from the lifelong learning hypothesis (e.g84,85) is that the value of positivity as a lexical cue steadily decreases as the vocabulary of positive words increases. When the set of positive words is relatively small, the ‘positive’ feature drives activation to a narrow subset of items, significantly reducing lexical competition and allowing these items to reach the recognition threshold more quickly. However, as the number of positive words increases with age, the same feature must spread activation to a much larger pool of candidates. This spreading of activation both reduces the activation boost per candidate and increases the inhibition of lexical competitors, thus slowing the accumulation of evidence needed for an entry to reach recognition threshold. As a result, positive valence has a reduced facilitating effect on word recognition in older participants. Also, gender differences might be related to a gender gap indicating that females are more likely to experience happiness86 and are happier with their life87 than males. These findings may be related to the theory of grounded cognition (e.g88), which posits that conceptual knowledge is rooted in sensorimotor and emotional experiences. According to this theory, the semantic content of words is partly constituted by simulations of perceptual, emotional, and motor states derived from previous experiences. Therefore, women’s happiness-related words would be associated with more vivid and accessible simulations, since women are more likely to experience happiness than men.

In conclusion, the results of this study show that discrete emotions influence word recognition beyond the effect of affective dimensions. This suggests that both dimensional and discrete emotional variables play a role in word processing, possibly at different stages22,29. Therefore, the emotional dimensional model alone does not capture all the nuances of emotional word content, emphasizing the importance of also examining emotional content through the lens of discrete emotions. Furthermore, the results indicate that individual differences, including personality traits, age, and gender, influence the recognition of words related to discrete emotions. This implies that the representation and processing of emotional content is affected by how individuals experience these emotions in their daily lives and across the lifespan70. The findings also highlight the need for careful experimental control and consideration of participant characteristics in studies of emotional word processing.

Data availability

The data and scripts used in this study can be downloaded from the following online open-access repository (Open Science Foundation): https://osf.io/rm7ej.

Change history

16 September 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the Acknowledgements section was incomplete. The Acknowledgements section now reads: “This study was supported by Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2023-149606NB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, U.E.), Rovira i Virgili University (2023PFR-URV-00196), and the Horizon Europe Framework Programme (HORIZON-MSCA-2023-SE-01. Ref.101182959)”.

References

Citron, F. M. M. Neural correlates of written emotion word processing: A review of recent electrophysiological and hemodynamic neuroimaging studies. Brain Lang. 122, 211–226 (2012).

Hinojosa, J. A., Moreno, E. M. & Ferré, P. Affective neurolinguistics: Towards a framework for reconciling Language and emotion. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 35, 813–839 (2020).

Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW): Instruction Manual and Affective Ratings. (1999).

Ferré, P. et al. How does emotional content influence visual word recognition? A meta-analysis of Valence effects. Psychon Bull. Rev. 32, 570–587 (2025).

Kousta, S. T., Vinson, D. P. & Vigliocco, G. Emotion words, regardless of polarity, have a processing advantage over neutral words. Cognition 112, 473–481 (2009).

Rodríguez-Ferreiro, J. & Davies, R. The graded effect of Valence on word recognition in Spanish. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 45, 851–868 (2019).

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M. & Cuthbert, B. N. Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychol. Rev. 97, 377–395 (1990).

Pratto, F. & John, O. P. Automatic vigilance: The attention-grabbing power of negative social information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 380–391 (1991).

Kousta, S. T., Vigliocco, G., Vinson, D. P., Andrews, M. & Del Campo, E. The representation of abstract words: Why emotion matters. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 140, 14–34 (2011).

Vigliocco, G., Kousta, S., Vinson, D., Andrews, M. & Del Campo, E. The representation of abstract words: What matters? Reply to paivio’s (2013) comment on Kousta et al. (2011). J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142, 288–291 (2013).

Larsen, R. J., Mercer, K. A. & Balota, D. A. Lexical characteristics of words used in emotional Stroop experiments. Emotion 6, 62–72 (2006).

Kuchinke, L., Võ, M. L. H., Hofmann, M. & Jacobs, A. M. Pupillary responses during lexical decisions vary with word frequency but not emotional Valence. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 65, 132–140 (2007).

Palazova, M., Sommer, W. & Schacht, A. Interplay of emotional Valence and concreteness in word processing: An event-related potential study with verbs. Brain Lang. 125, 264–271 (2013).

Keuleers, E. & Balota, D. A. Megastudies, crowdsourcing, and large datasets in psycholinguistics: An overview of recent developments. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 68, 1457–1468 (2015).

Haro, J., Hinojosa, J. A. & Ferré, P. The role of individual differences in emotional word recognition: Insights from a large-scale lexical decision study. Behav. Res. Methods. 56, 8501–8520 (2024).

Kuperman, V. Virtual experiments in megastudies: A case study of Language and emotion. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 68, 1693–1710 (2015).

Kuperman, V., Estes, Z., Brysbaert, M. & Warriner, A. B. Emotion and language: Valence and arousal affect word recognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143, 1065–1081 (2014).

Vinson, D., Ponari, M. & Vigliocco, G. How does emotional content affect lexical processing? Cogn. Emot. 28, 737–746 (2014).

Briesemeister, B. B., Kuchinke, L. & Jacobs, A. M. Discrete emotion norms for nouns: Berlin affective word list (DENN–BAWL). Behav. Res. Methods. 43, 441–448 (2011).

Ekman, P. Are there basic emotions? Psychol. Rev. 99, 550–553 (1992).

Frijda, N. H. Emotion, cognitive structure, and action tendency. Cogn. Emot. 1, 115–143 (1987).

Panksepp, J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions (Oxford University Press, 1998). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195096736.001.0001

Lindquist, K. A., Wager, T. D., Kober, H., Bliss-Moreau, E. & Barrett, L. F. The brain basis of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Behav. Brain Sci. 35, 121–143 (2012).

Campbell, J. & Burke, D. Evidence that identity-dependent and identity-independent neural populations are recruited in the perception of five basic emotional facial expressions. Vis. Res. 49, 1532–1540 (2009).

Elfenbein, H. A., Beaupré, M., Lévesque, M. & Hess, U. Toward a dialect theory: Cultural differences in the expression and recognition of posed facial expressions. Emotion 7, 131–146 (2007).

Briesemeister, B. B., Kuchinke, L. & Jacobs, A. M. Discrete emotion effects on lexical decision response times. PLoS ONE. 6, e23743 (2011).

Ferré, P., Haro, J. & Hinojosa, J. A. Be aware of the rifle but do not forget the stench: Differential effects of fear and disgust on lexical processing and memory. Cogn. Emot. 32, 796–811 (2018).

Huete-Pérez, D., Haro, J., Hinojosa, J. A. & Ferré, P. Does it matter if we approach or withdraw when reading? A comparison of fear-related words and anger-related words. Acta Psychol. 197, 73–85 (2019).

Briesemeister, B. B., Kuchinke, L. & Jacobs, A. M. Emotion word recognition: Discrete information effects first, continuous later? Brain Res. 1564, 62–71 (2014).

Santaniello, G. et al. Gamma oscillations in the Temporal pole reflect the contribution of approach and avoidance motivational systems to the processing of fear and anger words. Front. Psychol. 12, 802290 (2022).

Shafto, M. A., Abrams, L. & James, L. E. Age-related differences in the evaluation of highly arousing Language. Psychol. Aging. 39, 288–298 (2024).

van Hemert, D. A., van de Vijver, F. J. R. & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. Culture and crying: Prevalences and gender differences. Cross-Cult Res. 45, 399–431 (2011).

Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. & Bylsma, L. M. The riddle of human emotional crying: A challenge for emotion researchers. Emot. Rev. 8, 207–217 (2016).

Borkenau, P., Paelecke, M. & Yu, R. Personality and lexical decision times for evaluative words. Eur. J. Personal. 24, 123–136 (2010).

Ku, L. C., Chan, S. H. & Lai, V. T. Personality traits and emotional word recognition: An ERP study. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 20, 371–386 (2020).

Estes, Z. & Verges, M. Freeze or flee? Negative stimuli elicit selective responding. Cognition 108, 557–565 (2008).

Caplan, J. E., Adams, K. & Boyd, R. L. Personality and Language. in The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (eds. Carducci, B. J. & Nave, C. S.) 311–316 (Wiley, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118970843.ch52

Barańczuk, U. The five factor model of personality and emotion regulation: A meta-analysis. Person. Individ Differ. 139, 217–227 (2019).

Armstrong, T., Tomarken, A. J. & Olatunji, B. O. The moderating effects of contamination sensitivity on state affect and information processing: Examination of disgust specificity. Cogn. Emot. 26, 136–143 (2012).

Mueller, C. J. & Kuchinke, L. Individual differences in emotion word processing: A diffusion model analysis. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 489–501 (2016).

Carver, C. S. & White, T. L. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 319–333 (1994).

Parrott, D. J., Zeichner, A. & Evces, M. Effect of trait anger on cognitive processing of emotional stimuli. J. Gen. Psychol. 132, 67–80 (2005).

Silva, C., Montant, M., Ponz, A. & Ziegler, J. C. Emotions in reading: Disgust, empathy and the contextual learning hypothesis. Cognition 125, 333–338 (2012).

Ferré, P., Guasch, M. & Moldovan, C. Sánchez-Casas, R. Affective norms for 380 Spanish words belonging to three different semantic categories. Behav. Res. Methods. 44, 395–403 (2012).

Guasch, M., Ferré, P. & Fraga, I. Spanish norms for affective and lexico-semantic variables for 1,400 words. Behav. Res. Methods. 48, 1358–1369 (2016).

Hinojosa, J. A. et al. Affective norms of 875 Spanish words for five discrete emotional categories and two emotional dimensions. Behav. Res. Methods. 48, 272–284 (2016).

Stadthagen-Gonzalez, H., Imbault, C., Pérez Sánchez, M. A. & Brysbaert, M. Norms of Valence and arousal for 14,031 Spanish words. Behav. Res. Methods. 49, 111–123 (2017).

Hinojosa, J. A. et al. The Madrid affective database for Spanish (MADS): Ratings of dominance, familiarity, subjective age of acquisition and sensory experience. PLoS ONE. 11, e0155866 (2016).

Duchon, A. et al. One-stop shopping for Spanish word properties. Behav. Res. Methods. 45, 1246–1258 (2013).

Alonso, M. A., Fernandez, A. & Díez, E. Subjective age-of-acquisition norms for 7,039 Spanish words. Behav. Res. Methods. 47, 268–274 (2015).

Stadthagen-González, H., Ferré, P., Pérez-Sánchez, M. A., Imbault, C. & Hinojosa, J. A. Norms for 10,491 Spanish words for five discrete emotions: Happiness, disgust, anger, fear, and sadness. Behav. Res. Methods. 50, 1943–1952 (2018).

Ferré, P., Guasch, M., Martínez-García, N., Fraga, I. & Hinojosa, J. A. Moved by words: Affective ratings for a set of 2,266 Spanish words in five discrete emotion categories. Behav. Res. Methods. 49, 1082–1094 (2017).

Baayen, R. H. Analyzing Linguistic Data: A Practical Introduction To Statistics Using R (Cambridge University Press, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511801686

Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J. & Bates, D. M. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J. Mem. Lang. 59, 390–412 (2008).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023).

Lo, S. & Andrews, S. To transform or not to transform: Using generalized linear mixed models to analyse reaction time data. Front. Psychol. 6, 1171 (2015).

Lenth, R. V. et al. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.7.2. (2022). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. LmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Dodds, P. S. et al. Human Language reveals a universal positivity bias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 2389–2394 (2015).

Isen, A. M., Johnson, M. M., Mertz, E. & Robinson, G. F. The influence of positive affect on the unusualness of word associations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1413–1426 (1985).

Warriner, A. B., Kuperman, V. & Brysbaert, M. Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 english lemmas. Behav. Res. Methods. 45, 1191–1207 (2013).

Pexman, P. M., Hargreaves, I. S., Siakaluk, P. D., Bodner, G. E. & Pope, J. There are many ways to be rich: Effects of three measures of semantic richness on visual word recognition. Psychon Bull. Rev. 15, 161–167 (2008).

Citron, F. M. M., Weekes, B. S. & Ferstl, E. C. Arousal and emotional Valence interact in written word recognition. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 1257–1267 (2014).

Hofmann, M. J., Kuchinke, L., Tamm, S., Võ, M. L. H. & Jacobs, A. M. Affective processing within 1/10th of a second: High arousal is necessary for early facilitative processing of negative but not positive words. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 9, 389–397 (2009).

Larsen, R. J., Mercer, K. A., Balota, D. A. & Strube, M. J. Not all negative words slow down lexical decision and naming speed: Importance of word arousal. Emotion 8, 445–452 (2008).

Vieitez, L., Haro, J., Ferré, P., Padrón, I. & Fraga, I. Unraveling the mystery about the negative Valence bias: Does arousal account for processing differences in unpleasant words? Front. Psychol. 12, 748726 (2021).

Robinson, M. D., Storbeck, J., Meier, B. P. & Kirkeby, B. S. Watch out! That could be dangerous: Valence-Arousal interactions in evaluative processing. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 1472–1484 (2004).

Balota, D. A. et al. The english lexicon project. Behav. Res. Methods. 39, 445–459 (2007).

Barrett, L. F., Lindquist, K. A. & Gendron, M. Language as context for the perception of emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 327–332 (2007).

Cross, C. P., Copping, L. T. & Campbell, A. Sex differences in impulsivity: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 137, 97–130 (2011).

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C. & Schafer, W. D. Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 125, 367–383 (1999).

Kupfer, T. R. & Tybur, J. M. Pathogen disgust and interpersonal personality. Person. Individ Differ. 116, 379–384 (2017).

Meier, B. P. & Robinson, M. D. Does quick to blame mean quick to anger? The role of agreeableness in dissociating blame and anger? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 856–867 (2004).

Tobin, R. M., Graziano, W. G., Vanman, E. J. & Tassinary, L. G. Personality, emotional experience, and efforts to control emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 656–669 (2000).

Tybur, J. M., Lieberman, D., Fan, L., Kupfer, T. R. & de Vries, R. E. Behavioral immune Trade-Offs: Interpersonal value relaxes social pathogen avoidance. Psychol. Sci. 31, 1211–1221 (2020).

Druschel, B. & Sherman, M. F. Disgust sensitivity as a function of the big five and gender. Person. Individ Differ. 26, 739–748 (1999).

Haidt, J., McCauley, C. & Rozin, P. Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Person. Individ Differ. 16, 701–713 (1994).

Brebner, J. Gender and emotions. Person. Individ Differ. 34, 387–394 (2003).

Mohammad, S. & Yang, T. Tracking sentiment in mail: How genders differ on emotional axes. in Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity and Sentiment Analysis (WASSA 2.011) (eds. Balahur, A., Boldrini, E., Montoyo, A. & Martinez-Barco, P.) 70–79 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Portland, Oregon, 2011).

Aznar, A. & Tenenbaum, H. R. Gender and age differences in parent–child emotion talk. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 33, 148–155 (2015).

Christov-Moore, L. et al. Empathy: Gender effects in brain and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 46 Pt 4, 604–627 (2014).

Abbassi, E. et al. Lateralized affective word priming and gender effect. Front. Psychol. 9, 2591 (2019).

Kyröläinen, A. J., Keuleers, E., Mandera, P., Brysbaert, M. & Kuperman, V. Affect across adulthood: Evidence from english, dutch, and Spanish. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 150, 792–812 (2021).

Ramscar, M., Hendrix, P., Shaoul, C., Milin, P. & Baayen, H. The myth of cognitive decline: Non-linear dynamics of lifelong learning. Top. Cogn. Sci. 6, 5–42 (2014).

Namazi, A. Gender differences in general health and happiness: A study on Iranian engineering students. PeerJ 10, e14339 (2022).

Blanchflower, D. & Bryson, A. The gender well-being gap. Soc. Indic. Res. 173, 1–45 (2024).

Barsalou, L. W. Grounded cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59, 617–645 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2023-149606NB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, U.E.), Rovira i Virgili University (2023PFR-URV-00196), and the Horizon Europe Framework Programme (HORIZON-MSCA-2023-SE-01. Ref.101182959).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived the idea. J.H. conducted the data analyses and drafted the manuscript. P.F. and J.A.H. edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haro, J., Hinojosa, J.A. & Ferré, P. The influence of individual differences in the processing of words expressing discrete emotions: data from a large-scale study. Sci Rep 15, 25036 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10310-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10310-9