Abstract

Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) is one of the most expensive spices that is used globally for diverse medicinal, culinary and cosmetic purposes. Among the saffron producing countries, Iran ranks first whereas India produces only a fraction that is restricted exclusively to the Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The demand for saffron far exceeds its production in India necessitating the augmentation of saffron cultivation area involving suitable locations particularly in the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR). We explored the possibility of saffron cultivation under organic regime in the Eastern Himalayan state of Sikkim by conducting two-year cultivation trials at nine locations namely, Khamdong, Okhrey, Hilley, Khecheopalri, Yoksum, Pangthang, Dzongu, Phadamchen and Kyongnosla. The findings revealed the prevalence of edaphic and climatic conditions to support all developmental stages of saffron cultivation with location-specific differences. The major observations include (i) occurrence of first-year flowering of corms procured from Kashmir followed by robust vegetative growth at all the stated locations, (ii) effective multiplication and development of daughter corms, a crucially important event in saffron growth cycle, at all locations and (iii) occurrence of second-year flowering on new corms developed in Sikkim at five locations. The phytochemical marker components (crocin, safranal, picrocrocin) measured for saffron from certain locations corresponded to Grade 1 as per the norms adopted by the India International Kashmir Saffron Trading Centre (IIKSTC), Pampore, Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Taken together, the findings indicate the suitability of Sikkim Himalaya for saffron corm multiplication and commercial cultivation under complete organic regime and consequently hold significance for the farmers welfare at large.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crocus sativus L. (Family Iridaceae), commonly known as saffron, kesar and zafaran, is a perennial herbaceous flower crop. Saffron is a subhysteranthous, self-sterile, geophytic plant1. Being a male-sterile triploid, it is propagated exclusively by vegetative means from corms2. The characteristic lack of genetic variability in saffron could be solely ascribed to its sterility. The origin of saffron has been debated for over a century3,4. Earliest reference to its cultivation dates back to about 2300 BC at a village on the Euphrates called Azupirano meaning ‘saffron town’5. Precise identification of saffron dates from about 1700 − 1600 BC in the form of a fresco painting in the Palace of Minos in Crete. Assyrians and Babylonians evidently used saffron as medicine against various ailments during 668–627 BC. In Iran, saffron was first cultivated during the Kingdom of Media (708–550 BC). As mentioned in Rajtarangini written by Kalhana, in India saffron was used in Kashmir even before the reign of Lalitaditya in 750 AD. An elaborate analysis of evidence involving both ancient arts across history and recent research employing diverse genetic approaches suggests the emergence and domestication of saffron in ancient Greece4. Genetic studies convincingly reveal the auto-triploid origin of saffron (C. sativus) from two C. cartwrightianus cytotypes occurring naturally in Greece6,7.

Commercial saffron comprises the dried red stigmas often together with the yellowish style8,9. Recent surge in the interest in saffron owes to the pharmacological studies that provide convincing evidence for its multiple medicinal properties. Saffron is used in different medicine systems largely for its marked carminative, emmenagogue, febrifuge and anti-anxiety properties and also to cure arthritis, dysmenorrhea, asthma and cough10,11. Besides, its effective uses in folk medicine against scarlet fever, smallpox, colds, asthma, eye and heart diseases and cancer have been reported12. Pharmacologically, saffron possesses tyrosinase inhibitory13, anti-inflammator14, mutagenic15, cytotoxic, antigenotoxic16 as well as antiamyloidogenic activity against Alzheimer’s disease. These activities likely account for the reported effectiveness of saffron against various ailments. Saffron is in demand for flavouring food, perfumery and for dyeing17,18. The major chemical constituents of saffron, among several others, are three carotenoids namely, crocin, picrocrocin and safranal that render the characteristic colour, flavour and aroma, respectively19,20. Consequently, they most significantly determine the quality of commercial saffron.

Iran is by far the largest producer of saffron that meets most of its global demand. Other saffron producing countries include Afghanistan, India, Greece, Morocco, Spain, Italy, France, Azarbaijan21,22. Saffron production in India is restricted to Kashmir particularly Pampore (District Pulwama) and a few other places23,24. Since the domestic demand for saffron far exceeds its production, it is desirable to augment the production area by exploring the possibility of its cultivation beyond the traditional ones having considerable overlaps of edaphic and climatic conditions25. This is further necessitated in view of the fact that saffron production in Kashmir has substantially declined in recent years due to various factors including the prevailing climate change scenario24. The annual production decreased from 15.95 t in 1997 to 9.6 t in 201526. In this context, a few saffron cultivation trials have occasionally been attempted in certain locations in Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) including those in Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and others with varying extents of success9,27,28. However, more systematic studies aimed at identification of potential areas for saffron cultivation particularly in IHR are required with an emphasis on precise availability of growth conditions conducive for completion of different developmental events including corm multiplication.

Sikkim (27° 4’–28° 6’ N; 88° 3’–88° 56’ E), situated in the North-East, is the second smallest state of India that comprises a significant component of the Himalayan biodiversity hotspot (Fig. 1). Despite having a meagre 0.26% of the forested land in the country, it harbours > 6,000 plant species, 35% of the flora of India29. Sikkim has a unique distinction of being the first state in India to have fully organic certified status since 201630 and owns a significant agriculture landscape with numerous landraces/genotypes, carrying multiple beneficial traits of crops like rice. Recently, two cash crops from Sikkim namely, large cardamom (Amomum subulatum Roxb.) and dalley khorsani (Capsicum annuum L.) earned a Geographical Indication (GI) tag each. However, like elsewhere in the Himalayan region, the local people face the challenges of poverty and malnutrition31 due to threat to the traditionally practiced agriculture on account of fragmentation of land holdings coupled with the ongoing vast range of developmental activities. In the prevailing scenario, cultivation of appropriate high-value, low-volume agri-horticultural crops is highly desirable that could be expected to effectively augment and stabilize the economy of this tiny Himalayan state. The stated background prompted us to explore the possibility of cultivation of saffron under complete organic regime in certain specific parts of Sikkim with potentially suitable sets of conditions required for its growth and development. Here, we report the comprehensive success in terms of completion of diverse steps associated with saffron cultivation including corm multiplication in Sikkim Himalaya.

Materials and methods

Source of saffron corms

The saffron corms were procured from the well-recognized ‘All J&K Saffron Growers Development and Marketing Co-operative Association’, Jammu and Kashmir Union Territory, India. The transportation of corms was facilitated by JKHPMC (Jammu & Kashmir Horticultural Produce Marketing and Processing Corporation, Department of Horticulture, Govt. of J&K) with due permission of Department of Agriculture Production and Farmers Welfare (J&K UT). The corms were transported through air cargo and kept at room temperature with sufficient aeration to ensure proper corm health during storage at Sikkim University (Department of Horticulture) for a fortnight prior to planting. After planting, the specimen was collected from Okhrey, Sikkim, India (27°09′27.7″ N; 88°05′98.5″ E) at an altitude of 2490 m on November 22, 2022. It was identified by taxonomists Santosh K. Rai and Arun Chettri. The voucher specimen has been deposited in the herbarium of the Department of Botany, Sikkim University (SUH), under accession number SUH648.

Selection of cultivation trial sites

Based on the soil and climatic requirements for saffron cultivation, nine representative farmers’ fields were selected from five districts of Sikkim. At each location, trial was conducted in an area of 100 m2 (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Land preparation, planting and intercultural operations

Fertile land plots (100 m2 each) were brought to fine tilth in the month of September 2021 through deep ploughing, hoeing and removal of debris and stones. The soil beds of convenient length with 15 cm height and 90 cm width and separated by deep furrows for better drainage were prepared. Four hundred kg of enriched well decomposed Farmyard Manure (enriched FYM with Trichoderma viride) and 50 kg of vermicompost was incorporated to each plot at the time of bed preparation.

Saffron corms were planted at a depth of 10–12 cm maintaining a spacing of about 25 × 10 cm (row: row and plant: plant) keeping the apical bud upward. Plot was periodically irrigated during the dry spell (November to April) to maintain the optimum soil moisture level; during rest of the period, all locations received adequate rainfall. Required weeding and hoeing was done to keep the fields free of weeds. Fencing was done around the fields to protect them from wild animals and intruders, if any.

Measurement of agrometeorological and edaphic parameters

Among the agrometeorological parameters, air temperature and relative humidity were measured daily at each trial site using a digital thermo-hygrometer (Barigo No. 780, Barigo, Germany; precision: relative humidity 1%, temperature 1 °C). Composite soil samples for 0–10 cm depth collected from each plot using a steel corer of 10 cm diameter together with the one collected from Pampore (Kashmir) were analyzed for pH, total organic C, total Kjeldahl N, available P and K contents32,33.

Agrometeorological observations calculated for three blocks of a year each comprising 4 months are presented in Table 2; they broadly correspond to specific phase(s) of an annual cycle of saffron growth and development. Different phases include flowering, vegetative growth and initiation of corm multiplication (first block: November 2021-February 2022), corm multiplication, development, maturation and initiation of rest period (second block: March - June 2022) and completion of rest period and corm sprouting (third block: July-October, 2022). In general, the average ambient temperature range (minimum-maximum) was lowest and highest for the first and third block, respectively. Also, temperature varied substantially in a site-specific manner with the lowest and highest values recorded for Kyongnosla and Dzongu, respectively. In this regard, Hilley was comparable to Kyongnosla particularly during the first block (Table 2). All the sites, except Dzongu, experienced snow and/or frost mostly towards the second half of the first block; highest (74 d) and lowest (31 d) being in Hilley and Kyongnosla, respectively. Snow/frost exposure of the locations varied annually. For example, in the subsequent year (November 2022-February 2023), the number of days of snow/frost at Hilley was 64 (data not shown). Maximum rainfall (846–1036 mm) occurred during third block followed by that in the second (613–973 mm) and first block (21–28 mm), respectively (Table 2).

The physical properties of soil namely, bulk density, particle density and porosity (%) were estimated using standard protocol through pycnometer method. Bulk density was measured by calculating the mass of soil per given volume including solids and pore spaces and has been expressed as g/cm3. Particle density was measured as the mass of soil solids per given volume and expressed as g/cm3. Porosity corresponding to the volume not occupied by solids was expressed in terms of percentage. A digital pH meter (Systronics-335, Systronics, India; precision: 0.01) was used to determine soil pH in soil: water (1:5) suspension. Soil organic C was estimated by a colorimetric method without external heating34. Available P was determined following the ammonium–molybdenum blue method after extracting in 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate solution34. Total N was determined by the Kjeldahl digestion distillation method35 and exchangeable K by a digital flame photometer (Systronics, Model No. 130, Systronics, India) after extracting in ammonium acetate (pH 7) solution35.

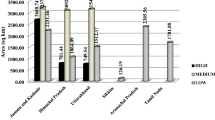

The results of soil sample analysis for its physico-chemical properties are shown in Fig. 2. The soil pH varied among different locations within a narrow range of 5.70 (Hilley) to 6.40 (Okhrey). The electrical conductivity values varied between 0.01 (Okhrey) and 0.10 dS/m (Kyongnosla) in Sikkim; the value was 0.05 dS/m for Kashmir soil sample. Organic carbon content was highest at Khecheopalri (2.60%) and the lowest at Phadamchen (1.09%). The magnitude of variation in nitrogen content was substantial. Among the Sikkim sites, it ranged from 214.7 (Okhrey) to 778.67 kg/ha (Yuksom) while the lowest contents (196 kg/ha) were recorded for Kashmir soil. Likewise, the P2O5 contents were in the range of 73.39 (Hilley) to 132.66 kg/ha (Phadamchen). The range of soil K2O content for Sikkim locations was 166.34 (Khamdong) to 376.91 kg/ha (Yuksom) while it was 509.96 kg/ha for Kashmir soil. The variation in soil bulk density, particle density and porosity among different locations including Kashmir was of a lower magnitude (Fig. 2).

Physico-chemical properties [(a) pH, (b) EC, (c) Organic carbon, (d) Nitrogen, (e) P2O5, (f) K2O, (g) Bulk density, (h) Particle density, (i) Porosity] of soil sampled from different locations, n = 3 ± SE. L1 (Khamdong); L2 (Okhrey); L3 (Hilley); L4 (Khecheopalri); L5 (Yuksom); L6 (Pangthang); L7 (Dzongu); L8 (Phadamchen); L9 (Kyongnosla); L10 (Pampore, Kashmir).

Flower harvesting, measurement of plant growth and corm multiplication

Flowers were picked manually during morning hours (before 10 AM) on the next day of anthesis. Number of flowers was recorded every day and the final count was calculated by summing up the numbers obtained from all pickings. Values were expressed per hectare basis. To determine the flower yield, average flower weight was measured on the basis of 15 randomly selected flowers. This was multiplied by the total number of flowers to obtain the final yield. Stigma, stamens and petals were separated using fine tipped forceps. Shade drying of the stigma was facilitated by spreading over the absorbent papers under the ambient conditions. Saffron yield was calculated after weighing the dried stigma and final value was expressed per hectare basis. The described growth parameters were measured for three replications. Under each replication, 15 randomly selected plants were tagged and utilised for recording of data. The data thus obtained from all replications was averaged to work out the final value. Number of sprouts per plant was counted after seven days of corm sprouting. Number of leaves per plant was counted at maturity. The length of 10 randomly selected leaves was measured by using a meter scale and average value was presented in centimeter. The days to first flowering was calculated by counting the days from sprouting till the first flower appeared. Likewise, the corm multiplication was assessed on the basis of number of corms recorded periodically from February to July. The corm multiplication ratio was determined in terms of the number of daughter corms per mother corm involving 15 tagged plants and the average value was calculated. The average weight of daughter corm was calculated by averaging the weight of 10 randomly selected daughter corms from the tagged plants.

Estimation of active chemical marker components in stigma

The dried stigma samples composited from each of the five sites namely, Khamdong, Okhrey, Khecheopalri, Yuksom and Pangthang in the first year and three sites namely, Khamdong, Okhrey and Pangthang were analyzed for the chemical marker constituents namely, picrocrocin, safranal and crocin. The analysis was done at the quality evaluation laboratory of India International Kashmir Saffron Trading Centre (IIKSTC), Pampore, Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir, India following standard protocol as detailed in ISO 3632-2:2010(E)36. The picrocrocin, safranal and crocin contents, measured spectrophotometrically, are expressed in terms of A1% 1 cm at 257, 330 and 440 nm on dry matter, respectively. In accordance with the practice followed for relative grade assignment to the saffron samples Grade 1 (G1) was assigned with following contents (A values): >70 (Picrocrocin), 20–50 (Safranal) and > 440 (Crocin).

Data analysis

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using OPSTAT online software (http://14.139.232.166/opstat/). Before performing ANOVA, the assumptions were tested for random sampling, normality and homogeneity of variance. Observations have been sampled randomly and were independent of each other. The data were tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk test and was found normally distributed within each group. The homogeneity of variance was tested using Levene’s test and the variance of the data within each group was equal. After applying ANOVA, the Tukey’s HSD test was done for post-hoc analysis to determine the significant difference among the locations for different traits.

Results

Plant growth, flowering and corm development

The sequence of different growth and development events associated with saffron cultivation trials conducted at the designated locations and salient features thereof are as follows:

First year flowering and plant growth

Location wise data were significantly different for almost all the parameters, except number of sprouts per plant and number of leaves per plant, where non-significant difference was observed among the locations based upon Tukey’s HSD test hypothesis. Following the sprouting of corms with an average of 1.29 (Khecheopalri) − 2.09 (Dzongu) sprouts per plant, flowering occurred at all the nine locations. However, the initiation of flowering in terms of time taken after sprouting varied. The earliest flowering was observed after 26 d at Phadamchen whereas it occurred as late as 46 d at Kyongnosla (Table 3). The flowering performance has been assessed in terms of number of flowers/ha, fresh flower yield (kg/ha) and saffron yield (stigma dry weight, g/ha) that varied quite widely among different locations. Thus, the observed range for these parameters was: flower number/ha, 16,650 (Phadamchem) to 201,650 (Pangthang); fresh flower yield (kg/ha), 5.99 (Phadamchen) to 56.46 (Pangthang); saffron yield (g/ha), 79.67 (Phadamchen) to 1,053.67 (Pangthang). Based on the saffron yield, highest performance was evident at Pangthang followed, in a descending order, by that at Khamdong, Khecheopalri, Yuksom, Dzongu, Okhrey, Kyongnosla, Hilley and Phadamchen, respectively (Table 3).

After flowering, plants continued to grow and as in case of flowering parameters, the growth performance in terms of leaf number per plant and leaf length varied in a wide range in a site-specific manner. Thus, the leaf number per plant ranged from 8.78 (Khecheopalri) to 14.05 (Dzongu) whereas the leaf length was found to be lowest (18.42 cm) at Yuksom and highest at Khamdong (34.41 cm) (Table 3).

First year corm multiplication and development

It was of particular interest to evaluate the multiplication and subsequent development potential of planted corms in terms of corm multiplication ratio (number of daughter corms developed per corm planted) and average weight of newly developed corms. Remarkably, the corm multiplication was observed at all the sites with variations in a narrow range and found to be non-significant (Table 3). However, highest corm multiplication ratio of 2.09 was recorded at Dzongu while the minimum value of 1.29 was noted at Khecheopalri. The average fresh weight of the newly developed corm was statistically significant and highest at Okhrey (19.36 g/corm) whereas the lowest value was observed at Kyongnosla (8.23 g/corm).

Interaction between location and year for plant growth, flowering and corm multiplication

In contrast to the first-year flowering performance, the second-year flowering from the daughter corms developed in Sikkim was observed only at five locations namely, Khamdong, Okhrey, Hilley, Khecheopalri and Pangthang (Table 4). No flowering was evident at Dzongu, Phadamchen and Kyongnosla whereas data could not be collected for Yuksom, so these sites were excluded from the analysis. The number of flowers/ha and fresh flower yield declined to strongly varying extents at different sites in the second year vis-à-vis the first year. Thus, the magnitude of decline in flower number was 0, 21, 54, 68, and 78% at Okhrey, Khamdong, Hilley, Pangthang and Khecheopalri, respectively. These values for fresh flower yield were 27, 29, 57, 63 and 80%, respectively. The observations in case of saffron yield differed in second year; yield was found to increase by 25% both at Khamdong and Okhrey whereas the same declined by 48, 51 and 56% at Hilley, Pangthang and Khecheopalri, respectively. As compared to first year, the leaf number per plant was substantially increased at Khamdong, Okhrey, Khecheopalri, Pangthang and Phadamchen by a magnitude ranging from 25 to 121%. It did not change at Yuksom and declined to some extent at Dzongu and Kyongnosla (Table 4). The interaction effect analysis showed that highest number of leaves (23.74) was observed in L1xY2 (Khamdong in second year), however; it was statistically at par with L5xY2 (Pangthang in second year) with non-significant difference (Table 4). In contrast, flowering parameters like number of flowers per hectare and flower yield per hectare was statistically superior (201650 and 56.46 kg, respectively) in L5xY1 (Pangthang in first year). Similarly, the saffron yield was highest (1053.67) in L5xY1. Corm multiplication ratio (4.54) was maximum in L5xY2. It is evident from the table that mean data of each location resulted from year 1 and year 2, was maximum in L5 (Pagthang) when compared to other locations, in case of all parameters. However, it was statistically at par with L1 (Khamdong) with non-significant difference in the case of number of leaves per plant and flower yield per hectare. The value of each parameter was averaged from all the locations to find out the data in each year, individually and it is evident that flowering parameters like number of flowers, flower yield and saffron yield were highest in Y1 (first year). Whereas, number of leaves per plant and corm multiplication ratio was highest in Y2 (second year) (Table 4).

Active chemical marker constituents

Quality of saffron was assessed in terms of the relative contents of three chemical marker constituents of saffron namely, crocin, picrocrocin and safranal for selected sites in both the years. Remarkably, the constituents at all considered sites corresponded to Grade 1 as prescribed by quality control laboratory of IIKSTC, UT of Jammu and Kashmir, India. In the first-year samples, the range of picrocrocin contents (A1% 1 cm at nm) was 73.48 (Khecheopalri) − 85.84 (Khamdong), that of safranal (A1% 1 cm at 330 nm) was 40.48 (Yuksom) − 47.67 (Okhrey); for crocin (A1% 1 cm at 440 nm), it was 230.71–254.65. It is noteworthy that the amount of measured constituents was slightly lower in second year than that in first year although they consistently corresponded to Grade 1 (Table 5).

Diverse events representing different developmental stages of saffron cultivation under organic regime in Sikkim Himalaya are summarised in Fig. 3.

Showing diverse events of saffron cultivation under complete organic regime in Sikkim Himalaya: (A) Corms procured from Kashmir (September, 2021), (B) Planting of corms on raised beds (October, 2021), (C) Flowering (November, 2021), (D) Multiplication of mother corms after flowering (November, 2021–April, 2022), (E) Mature corms (June-July 2022) (F) Flowering from the in situ multiplied corms (October- November, 2022) (G) Whole flowers, (H) Separated stigmas, (I) Dried saffron stigma. The photographs included in Fig. 3 were taken by the co-authors of this paper: Laxuman Sharma (A), Arun Chettri (B,C), Santosh K. Rai (D,E), Reshav Subba (F,G) and Rajesh Kumar (H,I).

Discussion

Present study aimed at exploring the possibility of saffron cultivation under the organically certified regime being practiced following NPOP (National Programme on Organic Production) standards in the Eastern Himalayan state of Sikkim since 2016. The major concerns, in addition to the occurrence of first-year flowering, were (i) whether the corms will multiply effectively and (ii) whether the newly developed corms (daughter) in Sikkim will receive sufficient low temperature exposure leading eventually to second-year flowering. The outcome of study, on the one hand, has direct implications for a meaningful augmentation of saffron cultivation area in India beyond Kashmir where it is cultivated traditionally and almost exclusively. Such an expansion is the need of the hour to ensure the fulfillment of domestic demand of this valuable spice and also in the wake of consistently declining saffron production in Kashmir owing to diverse reasons including those associated with the developing climate change scenario23. On the other hand, it is expected to add to the economic welfare of the farmer community and in turn the state of Sikkim. Saffron cultivation has been attempted at a few locations in Himalayan states such as Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and others9,27,28. However, the prevalence of a vast range of climatic conditions across IHR coupled with the specific biological requirements for accomplishment of all saffron crop cycle events clearly necessitates the intensification of efforts in this direction.

First year plant growth and flowering: suitability of growth conditions under organic regime

Despite small total area of the state of Sikkim (7096 km2), there are strong variations in climatic conditions that support diverse vegetation types contributing to the extraordinary richness of biodiversity37. Apparently, there is sufficient scope for introduction of a new crop species such as saffron at least in some suitable parts. The nine adopted sites for saffron cultivation trials in the present study were carefully chosen on the basis of understanding of the specific edaphic and climatic requirements for saffron cultivation, particularly in Kashmir, developed through literature search as well as interactions and elaborate discussions with the saffron experts and farmers during authors’ visits to Kashmir. The altitude of chosen sites ranges from 1404 (Dzongu) to 3300 m above mean sea level (Kyongnosla) (Table 1; Fig. 1). The annual agrometeorological data have been split into three distinct blocks, each comprising four months and generally corresponding to different plant growth and flowering process events. Such a split is intended to facilitate the correlative analyses of different growth and flowering observations. Temperature and rainfall are among the most important factors affecting the saffron cultivation. Indeed, a vernalisation requirement of 1000–1200 h of chilling with mean aerial temperature of 1-4o C has been reported for saffron38. Upon fulfillment of threshold chilling requirement, metabolic activities increase, hydrolytic enzymes are activated and carbohydrate reserves gradually become mobilized in order to support the growth and development. Present data concerning the availability of snow/frost days on different locations in Sikkim are consistent with the fulfillment of the necessary chilling requirement, albeit to varying extents (Table 2).

Due to the low water requirements, saffron cultivation is traditionally suited for low-rainfall areas1,39. In Italy, Greece and Spain, saffron is cultivated in areas having an annual rainfall between 250 and 700 mm1. This also holds for Kashmir valley with low precipitation rates but water scarcity below a certain threshold could potentially threaten the saffron production24. However, Sikkim is characterized by consistently high rainfall of up to 3000 mm annually40. Apparently, it represents a challenge for saffron cultivation and needs appropriate interventions to minimize the adverse impact on saffron crop. To this end, raised beds of 15 cm above ground coupled with deep furrows were used to facilitate drainage of water with minimum retention in soil surrounding the corm. The measured soil physical properties, in terms of bulk density, particle density and porosity (Fig. 2), allowed sufficiently low water retention at all the sites. Although soil pH in several parts of Sikkim is acidic, at the sites considered in this study, it ranged from 5.7 to 6.4 that is quite comparable to the pH (6.1) of Kashmir soil (Fig. 2).

Sikkim adopted the organic farming practice in 2003; subsequently, the entire cultivated area in the state was certified as per the norms of NPOP in 201630. The prohibition of all kinds of chemicals in the organic state of Sikkim over the last two decades has had discernible positive consequences for soil health in terms of multiple parameters. This is sufficiently reflected in a reasonably robust nutrient status of soils at all the sites. The measured values of soil organic C, N and P2O5 at most of the Sikkim sites were either greater or comparable to those measured for Pampore (Kashmir) soil except the organic C value at Phadamchen. The soil K contents were an exception in that they were consistently lower as compared to those of the Pampore soil (Fig. 2). Apparently, the high soil nutrient contents owe, in a large part, to the effective replenishment and maintenance of the relevant soil micro flora in the absence of any harmful chemicals under the prevalent organic agriculture practices since 2003. Several beneficial PGPRs have been isolated from the rhizosphere of different crops grown in Sikkim30. These inter alia include Bacillus luciferensis K2, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens K12 and Bacillus subtilis BioCWB41Bacillus cereus and Bacillus mycoides30 Enterobacter spp41 phosphate solubilizing bacteria (PSB) and IAA producing isolates42. Besides, we relied upon adding organic manure and vermicompost as nutrient supplements during saffron cultivation as they are quite compatible with the organic agriculture practices. Indeed, the replaceability of chemical fertilizers with organic and biological fertilizers for saffron cultivation has been suggested in a recent study reported from Iran43. Likewise, the application of vermicompost and mycorrhiza was demonstrated to have beneficial effects on the vegetative and reproductive growth of saffron44. Organic manure allows preserving C: N ratio by decomposing organic matter and mineralization within soil and additionally increases the soil fertility and productivity. Amending saffron with an organic fertilizer is beneficial for flower yield and mother corms size, that was more pronounced and significantly higher than the use of chemical fertilizer45. For example, the combined application of FYM and vermicompost is beneficial in increasing the saffron productivity and arresting the declining trend of soil organic carbon. Additionally, the application of FYM using corms of > 15 g resulted in highest yield of quality corms, alongside higher stigma yield and length of saffron46. Recently, the interactive effects of certain commercially available microbial inoculants on diverse aspects of saffron growth, corm multiplication and apo-carotenoid biosynthesis have been evaluated; trait-specific qualitative and quantitative influence was evident. Due to microbial interaction, saffron yield and quality increased as a consequence of modified metabolic parameters including enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defence47.

Saffron corms procured from Pampore (Kashmir) and planted in Sikkim sprouted well and flowered at all the stated locations. The observed first year flowering was expected given that the corms produced in Kashmir had already received the requisite amount of chilling. Obviously, they were physiologically equipped with all the necessary hormonal attributes required for various developmental processes including floral induction. Furthermore, all the needed nutrients to support vegetative and reproductive growth were available in appropriate amounts in Sikkim soil. However, despite the same physiological status of corms, the flowering performance parameters including the saffron yield differed substantially in a location-specific manner. This signifies the role of available soil nutrients in realization of the flowering potential of the otherwise physiologically competent corms. On the basis of first year saffron yield, the performance was in the following descending order: Pangthang > Khamdong > Khecheopalri > Yuksom > Dzongu > Okhrey > Kyongnosla > Hilley > Phadamchen. Interestingly, despite a similar altitude of Pangthang (1900 m) and Khamdong (1940 m), both in Gangtok district of Sikkim, the saffron yield was 42% in case of latter as compared to that in the former likely as a consequence of interactive influence of multiple prevailing factors in determining the saffron yield. Apparently, further research is required to get insight into the reasons for low saffron yield and identify appropriate strategies aimed at enhancing the same. The saffron flowering at certain locations in Himachal Pradesh (five) and Uttarakhand (one) located at different altitudes with diverse climatic characteristics in Western Himalaya involving the corms procured from Kashmir for a consecutive couple of years was recently reported27. Stigma yield was positively correlated with increased altitude and lesser rainfall27. Recently, saffron trials were conducted in several locations outside the traditional saffron growing area in Jammu and Kashmir, India with the objective of assessing location effects on saffron quality. The outcome indicated the possibility of growing good quality saffron outside traditional areas48. Based on Ecological Niche Modelling (ENM), Kumar et al.28 reported 06 states/UT in India including Jammu and Kashmir UT, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and Tamil Nadu to have the potential for saffron cultivation. Sikkim, together with Arunachal Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, was reported to have only low suitability class for saffron cultivation. A one-year trial at a single location (Shipgyer) in North Sikkim was made. In view of the vast differences in growth conditions, elaborate multi-location trials, even beyond the locations considered here, across the state would be rewarding.

Diverse aspects of corm multiplication and second year flowering

In order to ensure the self-reliance with respect to the perpetual availability of planting material (corms), it is crucially important that the mother corms procured from Kashmir multiply and develop effectively in Sikkim and then the newly developed corms receive the requisite chilling amount eventually leading to flowering. A major emphasis of the present study has been to convincingly address these two aspects. Quite interestingly, corm multiplication namely, the development of daughter corms from the mother corm, was evident at all the sites with the corm multiplication ratio ranging from 1.29 (Khecheopalri) to 2.09 (Dzongu). The latter was often inversely related with the corm fresh weight that varied from 8.79 (Dzongu) to 19.36 g (Okhrey). As an exception, at Kyongnosla, both low multiplication ratio as well as corm fresh weight were observed. There were strong site-dependent variations in the plant vegetative growth in terms of leaf number and length reflecting the photosynthetic potential. For example, the highest leaf length observed at Khamdong was nearly double that of the lowest observed at Yuksom. The observed differences could be ascribed firstly to the variations in soil nutrient contents and secondly to their uptake and utilization under the varying edaphic as well as temperature and moisture conditions. These two reasons need not be mutually exclusive. At some but not all sites, the fresh weight of newly developed (daughter) corms paralleled the leaf length which seems inter alia to be a consequence of differential allocation of photosynthates to the developing corms at different sites. As such, the robust corm multiplication observed here is highly encouraging and indicative of the possibility of self-reliant saffron cultivation in Sikkim. In a recent study, saffron cultivation in certain locations in Himachal Pradesh in Western Himalaya involving the corm procurement from Kashmir for a couple of consecutive years resulted in flowering but there were no data pertaining to corm multiplication27necessary for sustainable cultivation of saffron.

Although corm multiplication and development occurred at all the nine sites, the second-year flowering was evident only at five locations namely, Khamdong, Okhrey, Hilley, Khecheopalri and Pangthang. No flowering was evident at Dzongu, Phadamchen and Kyongnosla whereas data could not be collected for Yuksom. Flowering performance at the stated five locations in terms of flower number and flower yield declined vis-à-vis the first-year performance; the extent of decline ranged from low (< 30%; Okhrey, Khamdong) to high (> 50%; Hilley, Pangthang and Khecheopalri). As an exception, the flower number at Okhrey was comparable in the two years. Despite the moderately reduced flower number/yield, an increase in saffron yield was observed in the second year at Okhrey and Khamdong.

The most important reason for the year-on-year decline in the saffron flowering performance was the pathogenic damage of the corms. A random check was done by uprooting the developed underground corms and it revealed that up to one-third of the corms were affected depending upon the location (data not shown). Indeed, the corm rot complex disease caused by fungi such as Fusarium and other species as well as other microorganisms represents a major limiting factor substantially restricting the saffron production world over49. For example, in Kashmir, most of the saffron crop was found infected with corm rot49,50. The causal organisms are largely soil-borne and likely differ qualitatively and quantitatively in a location specific manner. Unlike elsewhere, owing to complete prohibition of agricultural use of chemicals in Sikkim, we relied on biological control for the management of corm rot. Accordingly, Trichoderma viride was used for corm treatment prior to planting as well as was added to the soil through FYM. This apparently provided reasonably high protection during the first year that was maintained in the second year albeit to a lesser extent. T. viride has been reported to effectively reduce the saffron corm rot51. Besides Trichoderma, beneficial effects of Azospirillum spp52 and Bacillus spp53 have been reported. It will be rewarding to test these and other organisms, both individually and in desired combinations, for their efficacy in reducing the incidence and magnitude of rot dependent damage in Sikkim. Excess water availability could inter alia aggravate the development of corm rot by way of providing necessary moist conditions for pathogen multiplication and maintenance. Despite high precipitation rates in Sikkim, the adopted interventions including raised beds, adjustment of corm-planting depth and deep intra-row furrows further supported by adequate soil properties led to effective drainage keeping the corms protected to a reasonable extent.

Although a certain threshold level and duration of low temperature exposure favours the saffron production, prolonged exposure to very low temperatures might inflict freezing injury. Cold stress has in fact been reported to adversely affect the saffron flower yield54 as well as the vegetative tissue differentiation and daughter corm formation. A lack of flower formation in corms incubated at 9 °C was reported55. In view of the lowest temperatures at Kyongnosla, of all the locations considered in the present study, freezing injury, among other factors, might have substantially contributed to the lack of second-year flowering. Certain physiological aspects of saffron response to freezing have been addressed. For example, electrolyte leakage in leaf as well as in whole underground part was observed to increase significantly with a decrease in temperature; simultaneously, the proline contents increased. The observed electrolyte leakage significantly decreased with increasing planting depth56. The damage to underground part would likely reflect in reduced flowering. Apparently, location-specific corm planting depth will have to be optimized to maximize the water drainage and simultaneously minimize the cold stress injury. The flower induction and formation in saffron have been shown to be differentially influenced by different hormones57. The possibility of altered hormonal regulation of flowering in response to the exposure to freezing temperature could not be excluded.

The existence of triploidy severely restricts the development of desired resistance to biotic (corm rot causing organisms) as well as abiotic (freezing, low- or excess-water availability etc.) stresses. Nevertheless, all organisms are inherently equipped to evolve adaptive strategies to withstand the deviations from optimal growth conditions. This constitutes an important reason for optimism that the continued saffron cultivation would along the way adapt to at least some parts of Sikkim in a near future.

The qualitative analysis of saffron produced for consecutive couple of years from some locations in terms of crocin, safranal and picrocrocin at the laboratory of Kashmir revealed it to be consistently Grade 1 as per the norms developed by the stated laboratory. The quality of produce sufficiently indicates the availability of necessary precursors as well as the effectivity of metabolic pathway involved in the synthesis of these secondary metabolites. This metabolic evidence strengthens the suitability of growth conditions for saffron cultivation in Sikkim Himalaya. Sikkim saffron produced under complete organic regime would be qualitatively exclusive and particularly superior for medicinal use where chemical toxicants are altogether undesirable.

Conclusion

Multi-location trials revealed the suitability of some parts of Sikkim Himalaya in terms of edaphic and climatic conditions for accomplishment of the entire biological cycle associated with cultivation of the high-value saffron. Thus, in the first year, the corms procured from Kashmir sprouted, flowered and led to the development of daughter corms. The latter received the required low temperature exposure and flowered in the second year. The phytochemical constituents (crocin, safranal and picrocrocon) corresponded to Grade 1 standards as per the norms adopted at IIKSTC, Jammu and Kashmir UT. The entire trials were conducted under complete organic regime being practiced in the state. A location-specific decline of flowering performance in the second year could inter alia be ascribed to pathogenic damage to corms despite the application of Trichoderma. It is planned to employ additional biocontrol agents in our future work. In a nutshell, the findings are encouraging and have direct implications for the welfare of farmers in the tiny Himalayan state of Sikkim with unique status of first completely organic state of India.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Gresta, F., Lombardo, G. M., Siracusa, L. & Ruberto, G. Saffron, an alternative crop for sustainable agricultural systems: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 28, 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2666-8_23( (2008).

Bayat, M., Rahimi, M. & Ramezani, M. Determining the most effective traits to improve saffron (Crocus sativus L.) yield. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 22(1), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-016-0347-1 (2016).

Koocheki, A. R. & Khajeh-Hosseini, M. Saffron: Science, Technology and Health (Woodhead Publishing, 2020).

Kazemi-Shahandashti, S. S. et al. Ancient artworks and Crocus genetics both support saffron’s origin in early Greece. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 834416 (2022).

Gadd, C. J. & Edwards, I. E. The Dynasty of Agade and the Gutian Invasion 2417–463 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1971).

Nemati, Z., Harpke, D., Gemicioglu, A., Kerndorff, H. & Blattner, F. R. Saffron is an autotriploid that evolved in Attica (Greece) from wild Crocus cartwrightianus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 136, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.03.022 (2019).

Schmidt, T., Heitkam, T., Liedtke, S., Schubert, V. & Menzel, G. Adding color to a century-old enigma: multicolor chromosome identification unravels the autotriploid nature of saffron (Crocus sativus) as a hybrid of wild Crocus cartwrightianus cytotypes. New. Phytol. 222, 1965–1980. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15715 (2019).

Zargari, A. Medicinal Plants (Tehran University, 1990).

Dhar, A. K. & Mir, G. M. Saffron in Kashmir-VI: A review of distribution and production. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 4(4), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1300/J044v04n04_09 (1997).

Mousavi, S. Z. & Bathaie, S. Z. Historical uses of saffron: identifying potential new avenues for modern research. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 1, 57–66 (2011).

Mykhailenko, O., Kovalyov, V., Goryacha, O., Ivanauskas, L. & Geogiyants, V. Biologically active compounds and pharmacological activities of species of the genus Crocus. A review. Phytochemistry 162, 56–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.02.004 (2019).

Abdullaev, F. I. Cancer chemopreventive and tumoricidal properties of saffron (Crocus sativus L). Exp. Biol. Med. 227, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/153537020222700104 (2002).

Li, C. Y. & Wu, T. Constituents of the stigmas of Crocus sativus and their tyrosinase inhibitory activity. J. Nat. Prod. 65, 1452–1456. https://doi.org/10.1021/np020188v (2002).

Hosseinzadeh, H. & Younesi Hani, M. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Crocus sativus L. stigma and petal extracts in mice. BMC Pharmacol. 2, 7 (2002).

Abdullaev, F. I. & Espinosa-Aguirre, J. J. Biomedical properties of saffron and its potential use in cancer therapy and chemoprevention trials. Cancer Detect. Prev. 28, 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdp.2004.09.002 (2004).

Abdullaev, F. I. et al. Use of in vitro assays to assess the potential antigenotoxic and cytotoxic effects of saffron (Crocus sativus L). Toxicol. in Vitro 17, 731–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-2333(03)00098-5 (2003).

Polunin, O. & Stainton, A. Flowers of the Himalaya (Oxford University Press, 1984).

Kyriakoudi, A., Ordoudi, S. A., Roldan-Medina, M. & Tsimidou, M. Z. Saffron, a functional spice. Austin J. Nutr. Food Sci. 3, 1059–1064 (2015).

Melnyk, J. P., Wang, S. N. & Marcone, M. F. Chemical and biological properties of the world’s most expensive spice saffron. Food Res. Int. 43, 1981–1989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2010.07.033 (2010).

Bathaie, S. Z. & Mousavi, S. Z. New applications and mechanisms of action of saffron and its important ingredients. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 50, 761–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390902773003 (2010).

Kafi, M., Kamili, A. N., Husaini, A. M., Ozturk, M. & Altay, V. An expensive spice saffron (Crocus sativus L.): A case study from Kashmir, Iran, and Turkey. Global perspectives on underutilized crops) (ed. Ozturk, M., Hakeem, K., Ashraf, M. & Ahmad, M.) 109–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77776-4_4 (Springer, 2018).

Cardone, L., Castronuovo, D., Perniola, M., Cicco, N. & Candido, V. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.), the King of spices: an overview. Sci. Hortic. 272, 109560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109560 (2020).

Husaini, A. M., Kamili, A. N., Wani, A. H., Teixeira da Silva, J. H. & Bhat, G. N. Sustainable saffron (Crocus sativus Kashmirianus) production: technological and policy interventions for Kashmir. Func Plant. Sci. Biotech. 4(2), 116–127 (2010).

Husaini, A. M. Challenges of climate change: Omics-based biology of saffron plants and organic agricultural biotechnology for sustainable saffron production. GM Crops Food. 5(2), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.4161/gmcr.29436 (2014).

Nehvi, F. A. et al. New emerging trends on production technology of saffron. Acta Hortic. 739, 375–382. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2007.739.49 (2007).

Ganaie, D. B. & Singh, Y. Saffron in Jammu & Kashmir. Int. J. Res. Geogr. 5, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.20431/2454-8685.0502001 (2019).

Kothari, D., Thakur, M., Joshi, R., Kumar, A. & Kumar, R. Agro-climatic suitability evaluation for saffron production in areas of Western Himalaya. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 657819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.657819 (2021).

Kumar, A., Devi, M., Kumar, R. & Kumar, S. Introduction of high-value Crocus sativus (saffron) cultivation in non-traditional regions of India through ecological modelling. Sci. Rep. 12, 11925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15907-y (2022).

Shenga, N. C. Status paper on biodiversity in Sikkim. Panda 1, 5–10 (1994).

Sherpa, M. T., Sharma, L., Bag, N. & Das, S. Isolation, characterization, and evaluation of native rhizobacterial consortia developed from the rhizosphere of rice grown in organic state sikkim, india, and their effect on plant growth. Front. Microbiol. 12, 713660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.713660 (2021).

Chhetri, D. R., Mahanta, J., Chettri, A. & Pradhan, A. Phytochemical and antioxidant attributes of Rhus chinensis mill., an edible wild fruit from Sikkim Himalaya. J. Plant. Sci. Res. 36(1–2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.32381/JPSR.2020.36.1-2.21 (2020).

Irshad, M. et al. Elevation-driven modifications In tissue architecture and physiobiochemical traits of Panicum antidotale Retz. in the Pothohar plateau, Pakistan. Plant Stress 11, 100430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2024.100430

Iqbal, U. et al. Unveiling the ecological dominance of button Mangrove (Conocarpus erectus L.) through microstructural and functional traits modifications across heterogenic environmental conditions. Bot. Stud. 65, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-024-00440-0 (2024).

Anderson, J. M. & Ingram, J. S. I. A handbook of methods 62–65 (CABInternational, 1993).

Allen, S. E., Grimshaw, H. M., Parkinson, J. A. & Quarmby, C. Chemical analysis of ecological materials. Blackwell Scientific Publications10.5555/19750622636 (1974).

ISO 3632-2 Technical Specification. Saffron (Crocus Sativus L.). Part 2 (test methods) (International Organization for Standardization, 2010).

Kholia, B. S. Pteridophytic Wealth of Sikkim Himalaya. Biodiversity of Sikkim Ferns 35–68 (Sikkim Biodiversity Board, 2011).

Nehvi, F. A. et al. Effect of trigger weather on saffron phenology under temperate conditions of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 14, 11085–11090 (2022).

Koocheki, A. R. Research on production of saffron in Iran: past trends and future prospects. Saffron Agron. Technol. 1(1), 3–21 (2013).

Dash, S. S. & Singh, P. Trees of Sikkim (ed. Aarawatia & Tambe. Biodiversity of Sikkim) 89–124 (IPR Department, Government of Sikkim, 2011).

Panneerselvam, P. et al. Antagonistic and plant-growth promoting novel Bacillus species from long-term organic farming soils from Sikkim, India. 3 Biotech 9(11), 416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-019-1938-7(2019).

Nan, T. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) under different citrus (Citrus reticulata Blanco.) based intercropping systems in long-term organic farming conditions. M.Sc. Dissertation, Sikkim University, India (2023).

Esmaeilian, Y., Amiri, M. B., Tavassoli, A., Caballero-Calvo, A. & Rodrigo-Comino, J. Replacing chemical fertilizers with organic and biological ones in transition to organic farming systems in saffron (Crocus sativus) cultivation. Chemosphere 307, 135537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135537 (2022).

Jami, N., Rahimi, A., Naghizadeh, M. & Sedaghati, E. Investigating the use of different levels of mycorrhiza and vermicompost on quantitative and qualitative yield of saffron (Crocus sativus L). Sci. Hortic. 262, 109027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.109027 (2020).

Koocheki, A. & Seyyedi, S. M. Relationship between nitrogen and phosphorus use efficiency in saffron (Crocus sativus L.) as affected by mother corm size and fertilization. Ind. Crops Prod. 71, 128–137 (2015).

Hussain, A., Illahi, B. A., Iqbal, A. M., Jehaangir, I. A. & Hussain, S. T. Agronomic management of saffron (Crocus sativus) – A review. Ind. J. Agron. 64(2), 147–164 (2019).

Naik, S., Bharti, N., Mir, S. A., Nehvi, F. A. & Husaini, A. M. Microbial interactions modify saffron traits selectively and modulate immunity through adaptive antioxidative strategy: organic cultivation modules should be trait and crop-specific. Ind. Crops Prod. 222, 119521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119521 (2024).

Sheikh, S. A. et al. Exploring Crocus sativus L. cultivation in new areas of North-Western Himalayas: the quality of saffron is location dependent. SKUAST J. Res. 25(1), 82–89 (2023).

Gupta, V. et al. Corm rot of saffron: epidemiology and management. Agronomy 11, 339 (2021). 10.3390/agronomy11020339.

Gupta, V., Kalha, C. S. & Razdan, V. K. Etiology and management of corm rot of saffron in Kishtwar district of Jammu and Kashmir, India. J. Mycol. Plant. Pathol. 41, 361–366 (2011).

Ahmad, M. et al. Management of corm rot of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) in Kashmir, India. Acta Hortic. 1200, 111–114. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2018.1200.18 (2018).

Sameer, S. S. et al. Effect of biofertilizers, biological control agents and soil amendments on the control of saffron corm rot (Crocus sativus L). Acta Hortic. 1200, 121–124 (2018).

Nehvi, F. A. et al. Integrated capsule for enhancing saffron productivity. Acta Hortic 1200, 95–100 (2018).

Koocheki, A. R., Mahallati, N., Alizadeh, M., Ganjali, A. & A. & Modelling the impact of climate change on flowering behaviour of saffron (Crocus sativus L). Iran. J. Field Crops Res. 7, 583–594 (2010).

Molina, R. V., Valero, M., Navarro, Y., Guardiola, J. L. & García-Luis, A. Temperature effects on flower formation in saffron (Crocus sativus L). Sci. Hort. 103(3), 361–379 (2005).

Koocheki, A. R. & Seyyedi, S. M. Mother corm origin and planting depth affect physiological responses in saffron (Crocus sativus L.) under controlled freezing conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 138, 111468 (2019).

Singh, D., Sharma, S., Jose-Santhi, J., Kalia, D. & Singh, R. K. Hormones regulate the flowering process in saffron differently depending on the developmental stage. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1107172 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge the help extended by Mr. Chowdhary Mohammad Iqbal, Director, Department of Agriculture Production & Farmers Welfare, Jammu & Kashmir UT in facilitating the procurement of saffron corms and expertise/suggestions on saffron cultivation by scientists (Dr. Sheikh Farhan Qadri, Dr. Sheikh Imran, Dr. Mohammad Younus) and farmers (Mr Abdul Majeed Wani, Mr Javed Gani) from Kashmir. We thank Dr. M. Salmani, IIKSTC, Jammu and Kashmir UT for phytochemical analysis of saffron samples and all the farmers in Sikkim on whose farms the study was conducted. Present work was financially supported by Sikkim University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK conceptualized and supervised the research. SSS designed the research, investigated the research and reviewed the manuscript. LS visualized and investigated the research, and edited the manuscript. DRC conceptualized the methodology and investigated the research. NB investigated the research and curated the data. SKR investigated the research and collected the data. AC investigated the research and prepared the figures. RK investigated the research, curated the data and written the original draft. RS: investigated the research and analyzed the statistical data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, R., Subba, R., Chettri, A. et al. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) cultivation under organic regime in Sikkim Himalaya and prevalence of conditions conducive for corm multiplication. Sci Rep 15, 25414 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10325-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10325-2