Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people believing in political COVID-19 conspiracies likely perceived that the government executed power unfairly (i.e., low procedural justice), which might have contributed to the questioning of the government’s legitimacy. This study examines the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and perceived procedural justice regarding COVID-19 policies during the peak and decay of the pandemic (May/June 2022–September 2023). Additionally, we considered the moderating role of economic and health threat. We tested our hypotheses using data from a five-wave study (N = 4939, quota-based). Latent growth curve analysis revealed a negative relationship between conspiracy beliefs (at Time 1) and the starting value of procedural justice (i.e., intercept). Furthermore, conspiracy beliefs were also negatively related to the change of procedural justice over time (i.e., slope): the lower people’s conspiracy beliefs at Time 1, the steeper their increase in procedural justice over time. Health threat weakened the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and the intercept of procedural justice, implying that people with stronger conspiracy beliefs reported lower resentment against COVID-19 policies the more they perceived health threat. Results show the effects of conspiracy beliefs on procedural justice throughout and potentially also beyond the pandemic, while also pointing to important moderators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some people felt that governments made unjustified political decisions (e.g., introducing lockdowns), climaxing in at that point forbidden demonstrations, where, among others, individuals with conspiracy beliefs expressed their dissatisfaction with governmental policies1,2,3. In other words, those people perceived low levels of procedural justice (i.e., the extent to which decision-making procedures by authorities are evaluated as fair or unfair) regarding governmental and societal responses to COVID-194. Procedural justice is one pillar through which a political system is legitimized, as it fosters acceptance, compliance, satisfaction, and trust in authorities5. Critically, procedural justice does not mean agreeing with the decision but, rather, assuming that it is based on a fair decision process in which different opinions have been considered. A lack of perceived procedural justice can foster intentions to overturn a government, which might have been one reason for the Capitol attack on January 6, 20216.

Despite the anecdotal evidence pointing to a link between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice, this relationship has barely been studied so far. Additionally, we have no knowledge of how conspiracy beliefs affect the perception of procedural justice over time, for example, whether procedural justice is restored after a societally critical event, here, after the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. To fill this gap, we studied the relation between conspiracy beliefs and perceived procedural justice from May/June 2022, when COVID-19 measures were gradually easing through the pandemic’s decay, up to September 2023 to examine the potential restoration of procedural justice. To gain a deeper understanding of the motivating forces, we paid particular attention to the moderating role of two types of threat prevalent during the pandemic: economic and health threat.

Conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice

Conspiracy beliefs are non-mainstream explanations for important events based on power holders who orchestrate secret plots without public oversight to suit their interests at the expense of others7,8. The alleged conspirators should be associated with lower perceived procedural justice, especially when the secret arrangement is the focus of the respective conspiracy theory. The COVID-19 pandemic inspired conspiracy theories, for instance, that the virus is a hoax or that governments instrumentalized the global health crisis to restrict citizens’ freedom9. Accordingly, individuals who lean towards COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs should be more likely to consider freedom-reducing measures unjustified and the result of an unfair decision-making process. Hence, people who believe in conspiracy theories about COVID-19 should have perceived low procedural justice during the pandemic (for further consideration of related concepts, see Supplement)10. The same might be true among those with a strong general propensity to believe in conspiracy theories—the so-called conspiracy mentality11,12,13. Individuals higher in such beliefs perceive those ruling the system as evil. Evidently, the higher such beliefs, the higher the general resentment against (governmental) institutions and processes14,15, implying that political processes are perceived as unfair and non-transparent. People high in conspiracy mentality assume that those in power only pursue the interests of the inner circle, questioning the justification of the implemented system12,16.

Accordingly, we predict that:

H1

The stronger peoples’ conspiracy beliefs—(a) stronger COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and (b) stronger conspiracy mentality—the less their perceived procedural justice.

Supporting this claim indirectly, Furnham (2023) reported a positive relationship between conspiracy beliefs and unjust world beliefs—the mindset that “good things happen to bad people”17. Other research found that leadership that empowers employees to participate in decision-making negatively relates to organizational conspiracy beliefs18.

Restoration of perceived procedural justice after the pandemic

Research has so far predominantly focused on correlates of conspiracy beliefs regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and in many other contexts19,20. However, much less is known about the long-term consequences of conspiracy beliefs, particularly the stability of these consequences when the event explained by the conspiracy decays. To close this gap, we sought to study the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice during the decay of the COVID-19 pandemic. The present study was conducted in Germany during the phase in which the government lifted the measures implemented to contain the spread of the virus. In May 2022, the German Health Minister at that time, Karl Lauterbach, appealed to the public to prepare for the upcoming autumn and winter. To this end, it was mandatory to wear face masks on public transport or get tested before entering a hospital. However, in February 2023, the health risk level for the population posed by the virus officially reduced, followed by the lifting of mandatory face mask wearing in March 202321, and the WHO declaring the end of a global health emergency in May 202322 (see Supplement for the rational underlying the selection of the measurement points). Given that the government removed the policies that originally caused the protests, perceptions of procedural justice might also be restored.

Yet, we consider an alternative trajectory for individuals with strong conspiracy beliefs more likely: Conspiracy beliefs are part of a worldview characterized by strong attitudes and beliefs23 that are hard to change24,25. Thus, it seems plausible that influences on daily life, such as the end of the pandemic and with it the lower relevance of the event originally explained by conspiracy theories, are less likely to affect conspiracy believers. In sum, individuals with stronger conspiracy beliefs are more inclined to cling to their perception of low procedural justice than those low in conspiracy beliefs. Accordingly, we predict that:

H2

The stronger peoples’ conspiracy beliefs—(a) stronger COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and (b) stronger conspiracy mentality—the less increase of procedural justice they will show over time.

Health and economic threat

The COVID-19 pandemic brought economic threat (e.g., potential unemployment) and health threat (e.g., getting seriously ill). We expect both to moderate the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice. Therefore, we draw on the uncertainty management model of procedural justice and the fairness heuristic theory, which state that people focus more on procedural justice in uncertain situations and use fairness information to evaluate authorities26,27,28. Accordingly, we assume that economic threat strengthens the negative relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice because (1) the emphasis on procedural justice is stronger (reinforcing the already low procedural justice perceptions of people with stronger conspiracy beliefs), and (2) the implemented COVID-19 measures by the government further fuel economic insecurities, and, thus, are perceived as unfair, resulting in an even worse evaluation of the government in handling the pandemic.

Indirectly supporting this reasoning, empirical work shows that economic threat negatively relates to adherence to COVID-19 measures29,30. One explanation for this result is that economic threat undermines feelings of agency and individual freedom. Hence, individuals who experience economic threat oppose COVID-19 measures implemented by the government as they put additional restrictions on them. Some people could not afford to stay home because this meant they would lack the money for their food and rent. Therefore, the perception of being economically threatened should give individuals with strong conspiracy beliefs additional reason to feel ignored, neglected, and unfairly treated by policymakers. In other words, individuals with strong conspiracy beliefs and a higher economic threat should perceive even lower procedural justice compared to people with strong conspiracy beliefs but with lower economic threat. Accordingly, we predict that:

H3

Economic threat moderates the relationship between conspiracy beliefs—(a) COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and (b) conspiracy mentality—and procedural justice. The higher the perceived economic threat, the stronger the negative relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice.

Contrary to economic threat, we assume the health threat weakens the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice. Specifically, in the presence of health threat, individuals, also those with stronger conspiracy beliefs, should appreciate the implemented restrictions by the government as they aim to reduce health threat and, thus, are in the people’s interest. In other words, even though people with stronger conspiracy beliefs have lower procedural justice perceptions associated with the government, they should positively evaluate the government’s handling of the pandemic, which might ultimately alter their perceptions of procedural justice. In line with this reasoning, previous empirical research showed that health threat is positively associated with adherence to COVID-19 measures29, potentially because health threat inspires caring, and individuals appreciate policymakers who implement COVID-19 measures as a means to keep communities safe. While appreciation of COVID-19 measures should already be high among individuals lower in conspiracy beliefs, the effect of health threat on acceptance of COVID-19 measures should also be especially pronounced among individuals higher in conspiracy beliefs.

Accordingly, we expect that people who hold strong conspiracy beliefs but also experience a higher health threat from COVID-19 to be less opposed to the government’s policies and, thus, perceive more procedural justice than individuals with strong conspiracy beliefs and lower perceived health threat as they likely perceive these measures as unnecessary. This reasoning leads to the following hypothesis:

H4

Health threat moderates the relationship between conspiracy beliefs—(a) COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and (b) conspiracy mentality—and procedural justice. The higher the perceived health threat, the weaker the negative relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice

The current research

We sought to test the hypotheses in a 5-wave longitudinal study (3-month time-lagged). As reasoned above, we also tested whether economic threat and health threat moderate the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and the trajectory of procedural justice over time, we also included this relationship in our analysis. However, the analysis was exploratory due to the lack of empirical research testing the long-term effects of threat perceptions in the context of conspiracy beliefs. Thus, we formulate the following research questions:

RQ1

Does economic threat moderate the relationship between conspiracy beliefs—(a) COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and (b) conspiracy mentality—and the trajectory of procedural justice over time?

RQ2

Does health threat moderate the relationship between conspiracy beliefs—(a) COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and (b) conspiracy mentality—and the trajectory of procedural justice over time?

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the ethics boards of the second author’s institution (LEK2022/017) and conducted in accordance with all relevant guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was preregistered (https://aspredicted.org/qfjf-mp8b.pdf), but the hypotheses and analyses reported here only broadly resemble the ideas of the preregistration. The specific analysis, applied exclusion criteria, and inclusion of relevant variables deviate from our original plan. A detailed report of the deviations and the reasons for the deviations can be found in the Supplement.

Participants and recruitment

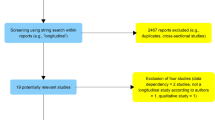

We recruited a German sample (quota-based sampling regarding age, gender, and education) via the panel provider respondi. Participants were financially reimbursed for their participation. People were eligible for participation when they gave their informed consent by checking a box, were between 18 and 69 years old, and spoke German fluently. Our goal was to recruit N = 5000 at Time 1. However, the provider invited more participants to account for potential dropouts and exclusions due to the quota-matching or low data quality. Of the 6555 people who clicked on the study, 5783 responded to the complete questionnaire. We excluded participants based on the following preregistered criteria: (1) no consent (n = 145), (2) did not finish the questionnaire (n = 370), (3) failing of two attention-checks (n = 209), (4) no agreement that they responded truthfully (n = 51), (5) participated multiple times (n = 211; we kept the data point completed first, in case IDs appeared twice), (6) not fluent in German (n = 11), and (7) did not sent their data to be used for research purposes (n = 773). Some participants fulfilled multiple exclusion criteria. To further improve data quality, we excluded n = 94 participants who showed repetitive answer patterns, n = 180 whose response times were faster than 50% of the average response time of the sample, and n = 101 who failed the first attention-check at Time 1, and did not invite them to the subsequent surveys. Excluding additional participants did not change the relationship between the variables (see Table S2 in Supplements). After excluding those individuals, the sample at Time 1 comprised N = 5171 participants. After requoting regarding age, gender, and education, our final sample at Time 1 consisted of N = 4939 participants (mean age = 44.73 years, SD = 14.92; 50.6% women). Most participants held a lower secondary school diploma (31.4%; 30.9% secondary school diploma, 18.3% abitur, 18.2% university degree) and were employed (63.2%). We invited all 4939 participants to the following waves and applied the described data quality checks for every wave. We document the exclusion process of Waves 2–5 in the Supplements (Table S3).

Measures

This study was part of a larger research project. In the following, we only present relevant variables to the current research question. A complete overview of all measures can be found in the Supplement. We included measures of procedural justice at all five measurement time points and, unless stated otherwise, report the assessment of the remaining variables at Time 1 in the analyses below.

Procedural justice (COVID-19 related)

Procedural justice regarding COVID-19-related politics was measured with four items adapted from Tyler et al. (1985; sample item: All sides are currently considered when making political decisions that affect the coronavirus policy)31. Participants indicated their agreement with the given statements on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely). McDonald’s ω ranged from 0.91 to 0.93.

Conspiracy mentality

We measured conspiracy mentality with the five items of the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (sample item: I think that many very important things happen in the world, which the public is never informed about)11. Participants rated their agreement with the given statements on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). McDonald’s ω was 0.90.

COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs

We assessed COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs with five items (sample item: Coronavirus (COVID-19) news outlets are exaggerating the numbers and the danger of COVID-19)9. Participants indicated their agreement with the given statements on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). McDonald’s ω was 0.89.

Economic threat

Perceived economic threat due to the COVID-19 pandemic was measured with nine items32. Participants finished the statement “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on my income and my work is…” on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (e.g., light/harmless/uncritical) to 7 (e.g., heavy/detrimental/threatening). McDonald’s ω was 0.95.

Health threat

Perceived health threat due to the COVID-19 pandemic was captured with nine items32. Participants finished the statement “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on my health is…” on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (e.g., light/harmless/uncritical) to 7 (e.g., heavy/detrimental/ threatening). McDonald’s ω was 0.95.

General perceptions of procedural justice (for exploratory analyses only; Time 5)

General perception of procedural justice was assessed with four items (sample item: All sides are currently considered when making political decisions). Participants indicated their agreement with those statements on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely). McDonald’s ω was 0.93.

We performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to ensure the statistical independence of conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice and present the results in the Supplement (Table S1).

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analysis with SPSS v. 29 and Mplus v. 8.1133,34. We tested our hypotheses and addressed the research question using latent growth curve analysis, which is based on structural equation modeling and allows for analyzing differences in intraindividual changes between individuals over time35. The observed items were treated as indicators for their respective latent factors.

First, we tested the longitudinal measurement invariance of procedural justice as it is a necessary precondition for latent growth curve analysis36. In the configural model, the observed indicators of procedural justice loaded on their a priori latent factor at each time point (configural invariance model). In the metric invariance model, we constrained the factor loadings of each indicator to be equal across all five time points (weak invariant model). In the scalar invariance model, we constrained the factor loadings and intercepts of each indicator to be equal across time (strong invariance model). We allowed item-specific covariances over time. We followed recommendations for model comparison in large samples, stating that changes < 0.010 in CFI (changes < 0.15 in RMSEA and changes < 0.03 in SRMR) imply no significant deterioration in model fit37. Applying these cut-off values suggests strong measurement invariance of procedural justice over time (see Table 1).

Before testing our hypotheses, we had to determine the actual temporal trajectory (i.e., slope) of procedural justice from Time 1 to Time 5. Accordingly, as a second step, we performed second-order latent growth curve analyses based on the strong invariance model. Particularly, we tested and compared an intercept-only model (Model 1), a linear model (containing the intercept and a linear slope; Model 2), and a quadratic model (containing the intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope; Model 3). In Model 3, we constrained the variance of the quadratic slope to zero to ensure a positive covariance matrix. In all three models, we set the factor loadings to 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 to represent the three-month retest-interval between measurement points. Intercepts and slope(s) were allowed to covary. As evident in Table 2, including the quadratic trend did not improve the fit beyond the linear model.

In the linear model, the intercept, which is the average baseline score, was 3.26 (SE = 0.02, z = 149.40, p < 0.001, 95% CI [3.22, 3.30]), and people differed regarding their average starting values (σ2 = 1.45, SE = 0.04, z = 35.34, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.37, 1.53]). On average, perceptions of procedural justice increased by 0.05 (SE = 0.01, z = 8.47, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.04, 0.07]) between measurement time points. However, peoples’ trajectories of procedural justice did not differ (σ2 = 0.002, SE = 0.01, z = 0.49, p = 0.627, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.01]). Finally, there was a positive covariance between the intercept and slope of procedural justice (γ = 0.05, SE = 0.01, z = 4.95, 95% CI [0.03, 0.07]) indicating that individuals with higher baseline values showed a steeper increase in procedural justice over time.

Third, we conducted hypotheses testing based on Model 2 (i.e., linear growth curve model). To this end, we added COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (at Time 1) as a latent variable in the model and regressed the intercept and slope of procedural justice on COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs to test H1a and H2a. We tested H1b and H2b in a different model by adding conspiracy mentality as a predictor.

Fourth, we performed moderation analyses to test H3, H4, RQ1, and RQ2 by adding either economic threat or health threat as moderators in the structural model. Therefore, we calculated latent interaction terms by multiplying COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs with economic threat (to test H3a and RQ1a) and health threat (H4a and RQ2a). Likewise, we multiplied conspiracy mentality with economic threat (H3b and RQ1b) and health threat (H4b and RQ2b) to create the latent interaction terms. Finally, we regressed the intercept and slope of procedural justice on COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, economic threat (or health threat to test H4a and RQ2a), and their respective interaction terms to test H3a and RQ1a. Lastly, we regressed the intercept and slope of procedural justice on COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, economic threat (or health threat to test H4b and RQ2b), and their respective interaction term to test H3b and RQ1b. We used the maximum likelihood parameter estimation (MLR) to account for possible non-normal distribution33. Small, insignificant residual variances were fixed to zero.

The outcomes of steps 3 and 4 are reported in the results section below.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in the Supplements (Table S5). We statistically compared individuals who participated at Time 1 to those who participated at Time 5 on all study-relevant variables (see Table S4 in the Supplements). Therefore, we consider the drop-out balanced as there were only small differences between both sub-samples (Cohen’s |d|= 0.04–0.21).

COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs as a predictor (H1a and H2a)

The results of the structural equation model (χ2 = 1525.43, df = 264; p < 0.001, scaling correction factor MLR = 1.27, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.03, 90% CI [0.03; 0.03], SRMR = 0.05) revealed that COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs were negatively related to the starting value of procedural justice as indicated by a negative relation to the intercept (γ = − 0.39, SE = 0.01, z = − 31.20, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.42, − 0.37]). Accordingly, H1a was supported as individuals with higher COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs at Time 1 reported lower levels of perceived procedural justice. Supporting H2a, there was also a negative relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and the slope of procedural justice (γ = − 0.01, SE = 0.004, z = − 3.11, p = 0.002, 95% CI [− 0.02, − 0.00]). This result indicates that individuals with higher values of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs at Time 1 (+ 1 SD: γ = 0.04, SE = 0.01, z = 5.22, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.02, 0.05]) showed a flatter trajectory of procedural justice over time than individuals with lower values of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (− 1 SD: γ = 0.06, SE = 0.01, z = 8.61, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.08]).

Conspiracy mentality as a predictor (H1b and H2b)

The results of the structural equation model (χ2 = 2111.30, df = 264; p < 0.001, scaling correction factor MLR = 1.27, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04, 90% CI [0.04; 0.04], SRMR = 0.06) revealed that conspiracy mentality is negatively related to the initial level of procedural justice as indicated by a negative relation to the intercept (γ = − 0.46, SE = 0.02, z = − 25.99, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.50, − 0.43]). This result supports H1b as individuals with higher conspiracy mentality at Time 1 showed lower initial values of procedural justice. Supporting H2b, conspiracy mentality was also negatively associated with the slope of procedural justice (γ = − 0.03, SE = 0.01, z = − 4.94, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.04, − 0.02]). In other words, individuals with higher values of conspiracy mentality (+ 1 SD: γ = 0.03, SE = 0.01, z = 3.08, p = 0.002, 95% CI [0.01, 0.04]) at Time 1 showed a flatter trajectory of procedural justice over time compared to individuals with lower values of conspiracy mentality (− 1 SD: γ = 0.08, SE = 0.01, z = 9.52, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.06, 0.09]).

Economic and health threat as moderators (H3, H4, RQ1, and RQ2)

COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs

Economic threat moderated the relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and the intercept of procedural justice and the slope (RQ1a). Contradicting H3a, the interaction term (COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs*economic threat) was positively related to the intercept (γ = 0.04, SE = 0.01, z = 5.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.03, 0.06]), which indicates that the relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and the starting value of procedural justice was weaker (i.e., a lower negative value), the higher the economic threat. In other words, the negative relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice was less pronounced in individuals perceiving more economic threat. This result is somewhat surprising as we anticipated that economic threat would strengthen the negative relationship. Likewise, the interaction term was positively related to the slope (γ = 0.01, SE = 0.002, z = 2.06, p = 0.039, 95% CI [0.00, 0.01]), indicating that individuals with stronger conspiracy beliefs (at the beginning) showed a steeper increase in procedural justice over time, the higher their economic threat (at Time 1).

Supporting H4a, the interaction term (COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs*health threat) was positively associated with the intercept of procedural justice (γ = 0.09, SE = 0.01, z = 10.40, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.07, 0.11]). This tells us that the higher the health threat, the weaker the negative relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice. Finally, regarding RQ2a, there was no relationship between the interaction term and the slope of procedural justice.

Conspiracy mentality

Economic threat moderated the relationship between conspiracy mentality and the intercept of procedural justice, but not the slope (RQ1b). Contradicting H3b, the interaction term (conspiracy mentality*economic threat) was positively associated with the intercept of procedural justice (γ = 0.03, SE = 0.01, z = 2.83, p = 0.005, 95% CI [0.01, 0.06]). The positive relationship indicates that the stronger the economic threat, the weaker the negative relationship between conspiracy mentality and the average starting value of procedural justice (again contradicting our anticipation that economic threat would strengthen this relationship).

Furthermore, supporting H4b, the interaction term (conspiracy mentality*health threat) was positively related to the intercept of procedural justice (γ = 0.07, SE = 0.01, z = 5.45, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.04, 0.09]), but not the slope (RC2b). In other words, the higher the perceived health threat, the weaker the negative relationship between conspiracy mentality and initial levels of procedural justice. This tells us that individuals with strong conspiracy beliefs, who perceived to be under health threat, report higher levels of procedural justice than individuals with strong conspiracy beliefs but under no health threat. The complete results of the structural models are summarized in Table 3. Follow-up analyses: For exploratory purposes, we also ran structural models separately for COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs and conspiracy mentality in which we included economic and health threat simultaneously as moderators38,39. For both conspiracy measures, the interaction term conspiracy beliefs*health threat positively related to the intercept of procedural justice (COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: γ = 0.09, SE = 0.01, z = 10.22, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.001, 0.01], conspiracy mentality: γ = 0.07, SE = 0.01, z = 5.30, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.04, 0.09]). Furthermore, the interaction term COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs*economic threat positively related to the slope of procedural justice (γ = 0.01, SE = 0.003, z = 2.30, p = 0.021, 95% CI [0.00, 0.01]). Yet, the relationship between the interaction term conspiracy beliefs*economic threat and the intercept of procedural justice no longer reached significance (COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: γ = 0.00, SE = 0.01, z = 0.42, p = 0.671, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.02], conspiracy mentality: γ = 0.00, SE = 0.01, z = 0.27, p = 0.784, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.03]), indicating that the unexpected positive relationship between the interaction term and procedural justice was due to the shared variance of economic and health threat.

Additional analysis

So far, we considered procedural justice regarding COVID-19 measures. We were also interested in whether conspiracy mentality and COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (both assessed at Time 1) would predict general (i.e., not COVID-19 specific) perceptions of procedural justice at Time 5—an indicator of general doubt about the fairness of governmental processes. Hence, we conducted multiple regression analysis with general and COVID-19-related perceptions of procedural justice (χ2 = 2418.61, df = 129; p < 0.001, scaling correction factor MLR = 1.33, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06, 90% CI [0.06; 0.06], SRMR = 0.05). Our results indicate a negative relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and general procedural justice (γ = − 0.12, SE = 0.03, z = − 3.76, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.19, − 0.06] and COVID-19-related procedural justice (γ = − 0.28, SE = 0.04, z = − 7.49, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.35, − 0.21]). There was also a negative relationship between conspiracy mentality and general procedural justice (γ = − 0.32, SE = 0.04, z = − 7.45, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.41, − 0.24]) and COVID-19-related procedural justice (γ = − 0.29, SE = 0.05, z = − 5.87, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.38, − 0.19]). These results show that general and specific conspiracy beliefs relate to general procedural justice perceptions one year later. The relationship seems to be highly stable and apply domain independently.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice, yielding five main results. First, stronger conspiracy beliefs (COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and conspiracy mentality) were related to lower perceptions of procedural justice. Second, conspiracy beliefs also predicted the trajectory of procedural justice, as individuals with stronger conspiracy beliefs showed a flatter increase in procedural justice over time. Third, the higher health threat perceptions, the weaker the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice. Fourth, economic and health threat did not moderate the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and the procedural justice trajectory (slope) over time. Five, all findings are consistent across COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs and conspiracy mentality.

The first result implies that individuals with stronger conspiracy beliefs perceived that the actions taken by the government during the COVID-19 pandemic were unjustified because they did not consider all relevant opinions. This result aligns with previous research, indirectly implying that conspiracy beliefs negatively relate to procedural justice17,18. According to the second result, the restoration of perceived procedural justice for people with strong conspiracy beliefs is substantially slower than for those with lower conspiracy beliefs. In addition, conspiracy beliefs assessed at the beginning of the pandemic also predicted perceived procedural justice in general (i.e., not just regarding decisions related to the pandemic) more than one year later. Given the high and stable correlational pattern between those constructs over time, we assume that conspiracy beliefs and (low) procedural justice perceptions form a stable interrelated belief system, which aligns with literature demonstrating that conspiracy beliefs and their negative consequences are highly stable and can shape (life) trajectories over a significant amount of time40,41.

Third, aligning with the uncertainty management model, suggesting that procedural justice perceptions are more pronounced in uncertain times, a stronger perceived health threat predicted a weaker relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice at the beginning of the study. This result aligns with our hypothesis and previous research showing that health concerns during the pandemic are positively associated with adherence to COVID-19 policies29,42. Moreover, the results showed that a stronger economic threat predicted a weaker relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice. However, the moderation effect by economic threat disappeared when controlling for health threat, suggesting that the significant correlations of economic threat were predominantly driven by the general threat perception shared by both types of threat. This might result from the fact that the primary threat of a pandemic is health-related, and the benefits of health-protecting behavior were prominently featured in the media and, thus, deemed important43. Hence, health threat seems to be the superior predictor and can buffer, at least to some extent, the impact of conspiracy beliefs on procedural justice.

Contributions and practical implications

Our research has several theoretical and practical contributions. First, our study provided initial empirical evidence for the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice using the COVID-19 pandemic as a contemporary, tangible, and highly relevant research context. We could also show the development of negative outcomes (i.e., low procedural justice concerning COVID-19 policies) of conspiracy beliefs over time. This is problematic for society because, in particular, low perceptions of procedural justice are impactful and come with negative consequences44. For instance, a lack of procedural justice makes it difficult for people to deal with burdening societal situations and carries the risk that they take matters (of justice) into their own hands45,46.

Second, and even more alarmingly, individuals with stronger conspiracy beliefs seem to stick to those low procedural justice perceptions, even when the critical event loses relevance. Additionally, our exploratory analyses provide initial evidence that procedural justice perceptions concerning COVID-19 measures might spill over to other areas (i.e., a general perception of low procedural justice). Third, even though threat perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic positively relate to conspiracy beliefs47, we have seen that, at least health threat, functions as a buffer, against the negative consequences of conspiracy beliefs.

This leads us to the practical implications derived from our research. On the one hand, politicians and other policymakers should monitor the emergence and development of conspiracy beliefs. In particular, they must be aware that their actions and statements have the capacity to inspire conspiracy beliefs, which in turn undermine the impact of policies (due to low procedural justice). On the other hand, these people might be able to combat conspiracy beliefs or their negative consequences due to their pivotal position in the political realm.

One way to maintain or restore procedural justice is to address criteria contributing to a fair decision-making process. For instance, Leventhal proposed six criteria: (1) consistency (i.e., decisions apply to everyone) (2) bias suppression (i.e., policymakers act independently of their self-interests) (3) accuracy (i.e., all information available must be considered) (4) correctability (i.e., the decision-making process must be monitored and mistakes must be corrected) (5) representativeness (i.e., concerns and values of all affected parties must be taken into account) (6) ethicality (i.e., acknowledging moral and ethical standards)48. Based on these criteria, people are sought to evaluate processes as (un)justified. If they find these criteria to be applicable, they should feel empowered, heard, and seen in politics49. And, in fact, people who perceive themselves as having a “voice” report higher levels of procedural justice50. However, the stable relationship between conspiracy beliefs and low procedural justice raises doubts that these otherwise effective measures to increase perceived procedural justice also work among conspiracy believers. Accordingly, future research should test whether it might be more challenging to recover procedural justice in individuals with strong conspiracy beliefs.

Limitations and future directions

The strengths of the presented research are the large quota-based sample, the longitudinal study design, and the consistency of the results across two different measures of conspiracy beliefs. Our work also has several limitations. First, even though we speak of the restoration of procedural justice, we did not collect data before or right at the onset of the pandemic. Therefore, we do not know the participants’ pre-pandemic levels of procedural justice. Additionally, our last measurement in September 2023 occurred only a couple of months after all COVID-19 measures were lifted. Thus, our data does not capture the development of procedural justice beyond the end of the pandemic. Accordingly, it would be highly informative if future research could track the interplay of conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice over a longer period, thereby assessing measures before and after an important societal event. Second, we only collected data in Germany. Hence, our results must be interpreted in light of the COVID-19 pandemic development in Germany (e.g., COVID-19 measures implemented, incidence rates, vaccination, and testing availability), but also the general characteristics of the political context (e.g., federal structure of Germany, growth of support for populist parties during the pandemic, formation of a new national government in spring 2022). Given that national characteristics are known to impact conspiracy beliefs51, future research might want to examine the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice in other countries to address this limitation. Third, the results presented are correlational. Thus, a causal interpretation is impermissible. Lastly, we rely on self-report scales, which pose the risk of common-method bias52. To minimize this risk, independent and dependent variables were measured at different time points53.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that conspiracy beliefs at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic (May/June 2022) negatively relate to perceptions of procedural justice concerning COVID-19 policies. Conspiracy beliefs also affected the restoration of procedural justice during the decay of the pandemic up to September 2023. In particular, individuals with lower conspiracy beliefs at the beginning showed larger increases in procedural justice over time compared to individuals with higher conspiracy beliefs. Finally, health threat weakened the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and procedural justice at the peak of the pandemic. To conclude, these results alarmingly show that even a year after the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, people with stronger conspiracy beliefs perceive that there is no justice for all.

Data availability

The data (https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.16511) and the syntax (https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.16512) supporting the results are publicly available.

References

Oltermann, P. Germany to crack down on Covid protesters in yellow star badges. (2022).

Connolly, K. German Jewish leaders fear rise of antisemitic conspiracy theories linked to Covid-19. The Guardian (2020).

Nocun, K. "It must be a plot!" - Coronavirus conspiracy theorists take streets in Germany. Heinrich Böll Stiftung Brussels (2020).

Sunshine, J. & Tyler, T. R. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law Soc. Rev. 37, 513–547 (2003).

Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E. & Manning, M. Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A systematic review of the research evidence. J. Exp. Criminol. 9, 245–274 (2013).

Kim, H. & Lee, J. A critical review of the US Senate examination report on the 2021 US Capitol riot. Front. Psychol. 14, 1038612 (2023).

Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. What are conspiracy theories? A definitional approach to their correlates, consequences, and communication. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 74, 271–298 (2023).

Van Prooijen, J.-W. & Douglas, K. M. Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Mem. Stud. 10, 323–333 (2017).

Pummerer, L. et al. Conspiracy Theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Per. Sci. 13, 49–59 (2022).

Van Prooijen, J.-W. Injustice without evidence: The unique role of conspiracy theories in social justice research. Soc. Just. Res. 35, 88–106 (2022).

Bruder, M., Haffke, P., Neave, N., Nouripanah, N. & Imhoff, R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: Conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 4, 225 (2013).

Sassenberg, K., Bertin, P., Douglas, K. M. & Hornsey, M. J. Engaging with conspiracy theories: Causes and consequences. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 105, 104425 (2023).

Hornsey, M. J., Bierwiaczonek, K., Sassenberg, K. & Douglas, K. M. Individual, intergroup and nation-level influences on belief in conspiracy theories. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 85–97 (2023).

Imhoff, R. & Bruder, M. Speaking (Un–)truth to power: Conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. Eur. J. Pers. 28, 25–43 (2014).

Freeman, D. et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol. Med. 52, 251–263 (2022).

Nera, K., Douglas, K. M., Bertin, P., Delouvée, S. & Klein, O. Conspiracy beliefs and the perception of intergroup inequalities. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 01461672241279085 (2024).

Furnham, A. Just world beliefs, personal success and beliefs in conspiracy theories. Curr. Psychol. 42, 2636–2642 (2023).

Van Prooijen, J.-W. & De Vries, R. E. Organizational conspiracy beliefs: implications for leadership styles and employee outcomes. J. Bus Psychol. 31, 479–491 (2016).

Uscinski, J. et al. The psychological and political correlates of conspiracy theory beliefs. Sci. Rep. 12, 21672 (2022).

Stasielowicz, L. Who believes in conspiracy theories? A meta-analysis on personality correlates. J. Res. Pers. 98, 104229 (2022).

Federal Ministry of Health. Coronavirus-Pandemie: Was geschah wann? https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/coronavirus/chronik-coronavirus.html.

Rigby, J. & Satija, B. WHO declares end to COVID global health emergency. (2023).

Winter, K., Hornsey, M. J., Pummerer, L. & Sassenberg, K. Public agreement with misinformation about wind farms. Nat. Commun. 15, 8888 (2024).

O’Mahony, C., Brassil, M., Murphy, G. & Linehan, C. The efficacy of interventions in reducing belief in conspiracy theories: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 18, e0280902 (2023).

Krekó, P. Countering conspiracy theories and misinformation. In Routledge handbook of conspiracy theories 242–256 (2020).

Van Den Bos, K. Uncertainty management: The influence of uncertainty salience on reactions to perceived procedural fairness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80, 931–941 (2001).

Uncertainty management by means of fairness judgments. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1–60 (Elsevier, 2002).

Van Den Bos, K. Fairness heuristic theory: Assessing the information to which people are reacting has a pivotal role in understanding organizational justice. In Theoretical and cultural perspectives on organizational justice 63–84 (Greenwich, 2001).

Lemay, E. P. et al. The role of values in coping with health and economic threats of COVID-19. J. Soc. Psychol. 163, 755–772 (2023).

Normand, A., Marot, M. & Darnon, C. Economic insecurity and compliance with the COVID-19 restrictions. Eur. J. Soc. Psych. 52, 448–456 (2022).

Tyler, T. R., Rasinski, K. A. & Spodick, N. Influence of voice on satisfaction with leaders: Exploring the meaning of process control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 72–81 (1985).

Klemm, C., Hartmann, T. & Das, E. Fear-mongering or fact-driven? Illuminating the interplay of objective risk and emotion-evoking form in the response to epidemic news. Health Commun. 34, 74–83 (2019).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide. (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, 1998).

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corp (2021).

Curran, P. J., Obeidat, K. & Losardo, D. Twelve frequently asked questions about growth curve modeling. J. Cogn. Dev. 11, 121–136 (2010).

Stoel, R. D., Van Den Wittenboer, G. spsampsps Hox, J. Methodological issues in the application of the latent growth curve model. In Recent developments on structural equation models (eds. Van Montfort, K., Oud, J. spsampsps Satorra, A.) vol. 19 241–261 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2004).

Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 14, 464–504 (2007).

Yzerbyt, V. Y., Muller, D. & Judd, C. M. Adjusting researchers’ approach to adjustment: On the use of covariates when testing interactions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40, 424–431 (2004).

Muller, D., Yzerbyt, V. Y. & Judd, C. M. Adjusting for a mediator in models with two crossed treatment variables. Organ. Res. Methods 11, 224–240 (2008).

Bierwiaczonek, K., Fluit, S., Von Soest, T., Hornsey, M. J. & Kunst, J. R. Loneliness trajectories over three decades are associated with conspiracist worldviews in midlife. Nat. Commun. 15, 3629 (2024).

Uscinski, J. et al. Have beliefs in conspiracy theories increased over time?. PLoS ONE 17, e0270429 (2022).

Morstead, T., Zheng, J., Sin, N. L., King, D. B. & DeLongis, A. Adherence to recommended preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of empathy and perceived health threat. Ann. Behav. Med. 56, 381–392 (2022).

Carrieri, V., De Paola, M. & Gioia, F. The health-economy trade-off during the Covid-19 pandemic: Communication matters. PLoS ONE 16, e0256103 (2021).

Cropanzano, R. S., Ambrose, M. L., Bobocel, D. R. & Gosse, L. Procedural Justice. In The oxford handbook of justice in the workplace (eds. Cropanzano, R. S. & Ambrose, M. L.) (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Edri-Peer, O. & Cohen, N. Citizens’ illegal behaviour as a response to unsatisfactory street-level encounters: The causal relationship between procedural justice and vigilantism. Public Management Review 1–21 (2024).

Moon, B. & McCluskey, J. Aggression toward teachers and negative consequences: The moderating effects of procedural justice. Victims Offen. 18, 1030–1045 (2023).

Heiss, R., Gell, S., Röthlingshöfer, E. & Zoller, C. How threat perceptions relate to learning and conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19: Evidence from a panel study. Personality Individ. Differ. 175, 110672 (2021).

Leventhal, G. S. What should be done with equity theory?. In: Social exchange (eds. Gergen, K. J., Greenberg, M. S. spsampsps Willis, R. H.) 27–55 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 1980).

Van Prooijen, J. W. Empowerment as a tool to reduce belief in conspiracy theories. In Conspiracy theories and the people who believe them (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Folger, R. Distributive and procedural justice: Combined impact of voice and improvement on experienced inequity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 35, 108–119 (1977).

Hornsey, M. J. et al. Multinational data show that conspiracy beliefs are associated with the perception (and reality) of poor national economic performance. Eur. J. Soc. Psych. 53, 78–89 (2023).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Kock, F., Berbekova, A. & Assaf, A. G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manage. 86, 104330 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.F.: formal analysis, writing—original draft; L.P.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, conceptualization, writing—review and editing; S.U.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, conceptualization, writing—review and editing; K.S.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Openness statement

Note, that the tested hypotheses are not preregistered as we deviated from the preregistration in several ways. We explain our reasoning for the deviations in the Supplements.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frenzel, S.B., Pummerer, L., Utz, S. et al. Conspiracy beliefs predict perceptions of procedural justice. Sci Rep 15, 30317 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10362-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10362-x