Abstract

Here, the encapsulation behavior of Cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]) is studied for six organic UV filters, i.e., benzophenone, homosalate, oxybenzone, dioxybenzone, sulisobenzone, and para aminobenzoic acid (PABA) using density functional theory (DFT). The thermodynamic stability of the designed systems is ensured by the values of interaction energies ranging from − 11.78 to -20.42 kcal/mol, with the highest value observed for dioxybenzone@CB[7]. Non-covalent interaction (NCI) analysis highlights the prevalence of van der Waals interactions in host-guest complexes, supported by quantum theory of atoms in molecule (QTAIM) analysis. The values of interaction energies of individual bonds in QTAIM analysis fall below 3 kcal/mol confirming the van der Waals interactions between the host and guest species. Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) and density of states (DOS) analyses indicate decreased energy gaps in the complexes compared to bare species, while natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis reveals charge transfer from host to guests with the highest observed for oxybenzone@CB[7] (-0.019|e|). Recovery time and desorption energy analysis highlight dioxybenzone@CB[7] as the most strongly adsorbed complex, while benzophenone@CB[7] being the least. The analysis also suggest a decrease in recovery time with increasing temperature (i.e., least for benzophenone@belt complex, i.e., 2.7\(\:\times\:\)10−6 s at 400 K). These findings illustrate CB[7] as an efficient host for encapsulating organic UV filters, offering a promising approach for reducing their negative ecological consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, water pollution has emerged as a significant global challenge. Increased awareness about the harmful effects of ultraviolet (UV) radiation on the skin has led to a surge in sunscreen usage, resulting in release of these chemical compounds into aquatic environments1,2. These compounds, when released into marine environments, disrupt aquatic ecosystems and pose risks to human and animal health. Their release into water systems occurs through direct deposition during recreational activities and indirectly via wastewater systems3. Coastal and marine tourism contribute significantly towards polluting nearshore waters, creating ecological dilemma. Once in aquatic ecosystems, these compounds undergo various chemical reactions, potentially forming harmful by-products that disrupt the delicate balance of marine life4,5. These chemical compounds, being lipophilic, when enter the food chain, also affect humans and animals.

Solar radiation reaching the surface of the Earth consist of shorter UVB radiation (wavelength 280–315 nm) and longer UVA radiation (wavelength 315–400 nm)6,7. The exposure to both UVB and UVA radiations is deleterious to the skin. UVB radiations lead to skin inflammation (sunburn), and erythema8. On the other hand, UVA radiations are mainly responsible for accelerating the premature aging of the skin9. Moreover, the excessive exposure to harmful UV radiations is the leading cause of skin cancer10,11. Suncare products contain UV filters that protect the skin from harmful UV radiations, by scattering, absorbing or reflecting sunlight. The efficacy of sunscreen in shielding UVB radiation is measured by its Sun protection factor (SPF), and against UVA radiation through the protection factor (UVA-PF)12. The UV filters can be organic, or inorganic in nature. Organic UV filters are classified based on their chemical structure, i.e., derivatives of benzophenones13,14, aminobenzoic acid15, salicylic acid16, triazines17, cinnamic acid18, dibenzoylmethane19, benzimidazole20, benzylidenecamphor21, and benzotriazole22. The common inorganic UV filters include titanium dioxide and zinc oxide23,24.

Benzophenone derivatives, such as benzophenone-8 (dioxybenzone) and benzophenone-3 (oxybenzone), are commonly used as UV filters in sunscreens but create significant environmental threats when released into aquatic ecosystems25. These compounds can disrupt marine environment by causing hormonal imbalances, oxidative stress and genotoxicity in marine life. Oxybenzone, for instance, is a major allergen and has been linked to contact dermatitis in humans. In aquatic systems, it disrupts metabolic pathways and can lead to fish mortality, developmental issues, and impaired growth in algae25,26. Similarly, benzophenone-4 (sulisobenzone) and other UV filters like homosalate and para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) contribute to oxidative damage, hormonal disruption, and growth inhibition in species like algae and Daphnia magna. These pollutants affect marine life, impairing growth, reproduction, and photosynthesis25,27. Research suggests various methods to remove these contaminants from water bodies to mitigate their harmful impacts28,29,30,31.

The biological processes like flocculation, filtration and adsorption have low efficiency for the removal of benzophenone-3 (BP-3), as reported by Li et al.32. Refering to adsorption for capture and removal of harmful pollutants, Belgacim et al. reported that n-ZIF-8 (ZIF = Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework) has potential as an adsorbent for greenhouse gas adsorption and Missaoui et al. studied the adsorption of volatile organic compounds using metal organic frameworks (MOFs)33,34,35. The nanofiltration and reverse osmosis are efficient processes for the removal of UV filters having diverse chemical and physical properties. Tsui et al. reported the successful removal of 99% UV contaminants from water through process of reverse osmosis36. However, reverse osmosis and nanofiltration processes are pressure-controlled and utilize more energy than membrane-based systems such as microfiltration and ultrafiltration (MF and UF)37,38. Moreover, the drawback associated with membrane-based systems is that UF membranes are unable to retain UV filter compound effectively. Photodegradation and advanced oxidation processes have greater removal efficiencies but are costly and limited for large-scale application39,40,41. Hence, the conventional treatment technologies have proved to be ineffective in the removal of these harmful UV filters from water.

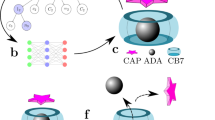

Fazli et al. performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations for the removal of benzophenone pollutants from wastewater via graphene oxide (GO) nanosheet42. The results indicate that the physical interactions exist between pollutant and GO nanosheet, i.e., the pollutants are stabilized via van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding with GO nanosheet42. Host-guest chemistry explores the formation of supramolecular complexes stabilized by non-covalent interactions, with macrocyclic molecules like cucurbit[n]urils (CBs), metallacycles, nanobelts, etc. offering remarkable recognition and binding abilities43,44,45,46,47. CB[7], with its symmetrical structure and hydrophobic cavity, is particularly suited for encapsulating diverse guests, including biologically active molecules43. Here, in our research work, six guests (i.e., benzophenone, homosalate, PABA, sulisobenzone, dioxybenzone and oxybenzone, see Fig. 1) are selected for encapsulation inside the host, i.e., cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]). Cucurbit[7]uril is pumpkin-shaped macrocyclic host, possessing hydrophobic cavity for encapsulation of guest molecules inside. Literature reports that CB[7] can form various types of interactions in host-guest complexes with different guests, depending on the type and nature of the guest42,48. CB[7] is chosen for this study due to its optimal size compatibility with the selected guests for encapsulation. This study focuses on the effective removal of organic UV filters via encapsulation inside CB[7]. It further explores the nature and strength of the interactions between the host and guest molecules, providing valuable insights into their binding dynamics. Additionally, the research aims to analyze the energy gaps and investigate the charge transfer processes within the host-guest complexes, offering a comprehensive understanding of their electronic properties.

Methodology

ORCA 5.0.149 is employed for density functional theory (DFT) calculations. A range-separated functional (ωB97X-D3)50 and triple zeta basis set (def2-TZVP)51 are used for geometry optimization. Frequency calculations are also performed by employing the same method (ωB97X-D3/def2-TZVP) in order to confirm the true minima nature of the optimized bare host, guest and host-guest complexes. ωB97X-D3 accurately predicts the noncovalent interactions between the host and guest in the designed complexes and is extensively used in literature for this purpose52. The ORCA is selected for computations primarily for its implementation of the wB97X-D3 functional, which includes the third-generation Grimme dispersion correction (D3), providing improved treatment of dispersion interactions that is critical for accurately modeling the system’s non-covalent interactions. Additionally, ORCA’s implementation of the Resolution of Identity (RI) approximation significantly reduced computational cost without compromising accuracy. Moreover, ORCA’s superior parallelization capabilities are better suited to our available computational infrastructure, enabling more efficient resource utilization across our computing cluster53. For the visualization of optimized structures, Chemcraft54 and GaussView 5.055 are used. The noncovalent interaction analyses (noncovalent interaction index and quantum theory of atoms in molecules) are performed at ωB97X-D3/def2-TZVP, whereas the electronic properties (i.e., frontier molecular orbital, density of states, and electron density difference analyses) are performed at B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP56,57,58, due to the reported greater accuracy of the method in predicting the HOMO/LUMO energies and the energy gaps56,57,58. Although the long-range hybrid functional (ωB97X-D3) is known for its accuracy, recent studies have shown that it does not always reproduce accurate HOMO/LUMO energies59. NBO 7.0 package60 is employed for natural bond orbital (NBO) charge analysis. Multiwfn61 is used to analyze data obtained from ORCA and visual molecular dynamics (VMD) software version 1.9.4a4862 is used for visualization. Further, Eq. (1) is used to calculate interaction energies (Eint) of the complexes.

In this equation, interaction energy of the designed complex is represented by Eint, whereas Ecomplex, ECB[7] and Eorganic guest represent the energies of the host-guest complex, bare host and guest, respectively. Moreover, NCI47,63 and QTAIM45,64 analyses provide detailed investigation of noncovalent interactions. 2D RDG maps of NCI depend on electron density (ρ) and reduced density gradient, i.e.,

The topological parameter of QTAIM i.e., the total energy density H(r) is obtained by addition of local potential and kinetic energies i.e., G(r) and V(r), respectively.

Similarly, the Eint of individual bonds is determined as follows,

The Eint values between 3 and 10 kcal/mol demonstrate the presence of electrostatic interactions between the host and guest in the complexes44,46. However, the values less than 3 kcal/mol indicate the existence of van der Waals forces. Furthermore, recovery time is determined via transition state theory, using following Eq.

Here, υ signifies the attempt frequency, T is temperature of the system, and k represents the Boltzmann constant having value of 8.62 × 10− 5 eV K− 1.

Results and discussion

Geometric parameters and interaction energies

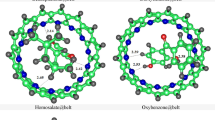

Cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]), a cavity containing host is selected in the study for complexation with organic compounds, as it is the best fit for studied guests. Six organic compounds (commonly used in sunscreens) are encapsulated as guests inside the host CB[7], for the formation of host-guest complexes. Interaction energies (Eint) for the most stable configuration of the complexes and interaction distances between the host and guests are reported in Table 1. The complexes are illustrated in Fig. 2. Figure 2 shows that the guests are stabilized at the center of the host’s cavity. The interaction energies for the complexes range from − 11.78 to -20.42 kcal/mol, showing a significant interaction between the host and guest specie. The values of Eint for benzophenone@CB[7] and PABA@CB[7] are lesser compared to the other complexes, i.e., -11.78 and − 11.82 kcal/mol, respectively. The reason can be attributed to the greater interaction distances (Dint) between the host and guest for these two complexes, i.e., ranging from 2.32 to 2.71 and 2.01–2.76 Å, respectively.

The highest Eint is observed for dioxybenzone@CB[7] complex, accompanied by the shortest Dint i.e., ranging from 2.17 to 2.30 Å. The other three complexes also show considerable values of Eint and Dint, i.e., Eint for sulisobenzone@CB[7], homosalate@CB[7] and oxybenzone@CB[7] are − 20.37, -19.21, and − 15.51 kcal/mol, respectively. Similarly, the Dint for sulisobenzone@CB[7], homosalate@CB[7]and oxybenzone@CB[7] range from 2.40 to 2.55, 2.51–2.69, and 1.98–2.63 Å, respectively. Overall, the values of Eint reveal that guests are well stabilized inside the cavity of host, resulting in stable host-guest complexes. Additionally, Fig. 2 shows that the lesser Dint exist between the H atoms of the guests and O atoms of the host CB[7], compared to the other atoms due to the geometry of CB[7].

Moreover, it is quite evident that the CB[7] cavity is large for PABA molecule. The encapsulation of these molecules (guests) inside CB[6] was tried, but the molecules didn’t fit best there. That’s why CB[7] is chosen to encapsulate all the guest molecules, as the comparative analysis is performed. The results of interaction energies for PABA encapsulated inside CB[6] shows that the complex i.e., PABA@CB[6] (Eint= -14.02 kcal/mol) is more stable compared to PABA@CB[7] (Eint= -11.78 kcal/mol). The values are reported in Table S2 (of supporting information).

Table 2 reports the adsorption or interaction energies (Eint) of the designed guest@CB[7] complexes alongside representative values reported in the literature. All our calculations are performed at the wB97XD-D3/Def2-TZVP level of theory in the gas phase, yielding interaction energies ranging from − 11.78 to − 20.42 kcal mol⁻¹. Among the studied systems, dioxybenzone@CB[7] and sulisobenzone@CB[7] showed the strongest binding affinities, with interaction energies of − 20.42 and − 20.37 kcal mol⁻¹, respectively. These values are comparable to or stronger than several reported CB[7] complexes such as D2–CB[7] (− 15.38 kcal mol⁻¹), D3–CB[7] (− 13.68 kcal mol⁻¹), and piperine–CB[7] in the gas phase (− 21.80 kcal mol⁻¹), indicating favorable host–guest interactions in our systems. Though variations in computational methodology and solvent models exist among the literature values (e.g., M06-2X/6–31 + G(d, p), B3LYP/6-31G(d)), the comparative trend still highlights the competitive binding nature of guest species used in our study. Notably, some systems reported in solution or with protonated guests (e.g., DOXH⁺–CB[7], − 53.54 kJ mol⁻¹) show enhanced binding due to additional electrostatic interactions. Overall, the reported interaction energies align well with literature data, reinforcing the stability and inclusion potential of CB[7] for sunscreen-based guests.

NCI analysis

Noncovalent interactions are of significant importance in many chemical and biological systems. Noncovalent interaction index (NCI) or reduced density gradient (RDG) analysis facilitates the evaluation of host-guest complementarity, along with the extent to which the weak host-guest interactions play a role in stabilizing the complex. Figure 3 displays 3D isosurfaces and 2D RDG maps of NCI analysis for the designed supramolecular complexes. 3D images show the green and red colored patches indicating the van der Waals (vdW) interactions and steric effects (repulsions). By carefully examining the isosurfaces, it is observed that a greater number of green colored patches are dispersed in the cavity of the host, i.e., between the guest and walls of the host, indicating the vdW interactions between the host and guest. Moreover, some red colored patches are noticed existing inside the rings of the host and guests, indicating steric effects (SE). Likewise, in 2D RDG maps of the complexes, the green and red spikes are observable, validating the findings of 3D isosurfaces.

For benzophenone@CB[7] complex, green patches are present in the vicinity of benzophenone, implying vdW interactions as the reason behind stability of the host-guest complex (benzophenone@CB[7]). The red patches, representing SE are found in the rings of CB[7] and benzophenone, individually. Similarly, in 2D map, the green and red spikes are visible, justifying the existence of vdW and SC. Similarly, for all the other complexes, the green patches are more prominent between the host and guests in the 3D maps, whereas the red patches are predominantly found within the rings of host and guest species. Moreover, the greater green and red spikes are present compared to the blue spikes, indicating that the dominant forces for host-guest stability are weak van der Waals interactions. In comparison among all the complexes, two of the designed supramolecular complexes (i.e., benzophenone@CB[7] and PABA@CB[7]) exhibit lesser number of green colored patches compared to the others, demonstrating comparatively less van der Waals interactions. Moreover, 3D map of dioxybenzone@CB[7] complex shows greater green patches, justifying the highest Eint, followed by sulisobenzone@CB[7], homosalate@CB[7] and oxybenzone@CB[7], respectively. Overall, the interaction energies (Eint) of the complexes follow a trend i.e., dioxybenzone@CB[7] (-20.42 kcal/mol) > sulisobenzone@CB[7] (-20.37 kcal/mol) > homosalate@CB[7] (-19.21 kcal/mol) > oxybenzone@CB[7] (-15.51 kcal/mol) > PABA@CB[7] (-11.82 kcal/mol) > benzophenone@CB[7] (-11.78 kcal/mol).

QTAIM analysis

Bader’s quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analysis describes the nature of bonding in molecular systems. The topological parameters obtained via QTAIM are; bond critical points (BCPs), local kinetic energy V(r), local potential energy G(r), electron density ρ(r), Laplacian of electron density ∇2ρ(r), and total electron energy density H(r). By analyzing these topological parameters, the nature as well as strength of interactions can easily be predicted. Figure 4 presents BCPs of the designed supramolecular complexes, whereas Table S1 reports the QTAIM topological parameters. The least number of BCPs are found for benzophenone@CB[7] and PABA@CB[7], i.e., 17 and 16, respectively. These two complexes also exhibit the lesser Eint and vdW interactions as predicted via interaction energy and NCI analyses. The other complexes show comparatively greater number of BCPs, i.e., 30, 23, 19 and 19 for homosalate@CB[7], sulisobenzone@CB[7], dioxybenzone@CB[7], and oxybenzone@CB[7], respectively.

The electron density ρ(r) and Laplacian of electron density ∇2ρ(r) at BCPs for benzophenone@CB[7]range from 0.0007 to 0.0110 a.u and 0.002–0.043 a.u, respectively. Similarly, local kinetic energy V(r), local potential energy G(r), and total electron energy density H(r) range from − 0.0003 to -0.0063 a.u, 0.0004–0.0085 a.u, and 0.0002–0.0022 a.u, respectively. Moreover, the ratio -V/G and interaction energy of individual bond (Eint) at BCP range from 0.60 to 0.79 a.u and 0.09–1.98 kcal/mol, respectively. The positive values of ∇2ρ(r) show the presence of noncovalent interactions in the complex. The smaller values of ρ(r) and ∇2ρ(r) indicate that the weaker van der Waals interactions are responsible to stabilize the benzophenone inside CB[7]. Further, smaller Eint (less than 3) states the absence of hydrogen bonding in the complex, justifying the stability via vdW interactions. A similar pattern is observed for homosalate@CB[7] and sulisobenzone@belt complexes in Table S1, i.e., the smaller positive values of ρ(r) and ∇2ρ(r), representing the stabilization of the guests inside host specie via weak vdW interactions. Moreover, the values of Eint less than 3 at all CPs, showing the absence and presence of electrostatic attraction and vdW interactions, respectively.

The ρ(r) and ∇2ρ(r) of the other three complexes, i.e., dioxybenzone@CB[7], PABA@CB[7]and oxybenzone@CB[7]also show the presence of noncovalent interactions. For all the three complexes, the Eint for one of the BCP falls in the range of hydrogen bond (i.e., greater than 3), while all the other values are in the range of vdW interactions. Overall, QTAIM analysis reveals that the guests are stabilized inside host via noncovalent interactions, where comparatively lesser BCPs and interactions are observed for benzophenone@CB[7] and PABA@CB[7]complexes. Hence, QTAIM analysis corroborates with NCI and interaction energies analysis, revealing the nature and comparative strength of interactions in the designed supramolecular host-guest complexes.

FMO analysis

Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis provides comprehensive insights about the electronic properties of complexes. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels and energy gaps of the complexes are analyzed in order to find the contribution of HOMO and LUMO of the host and guests in the formation of complexes. Figure 5 demonstrate the HOMO, LUMO isodensities of the host (CB[7]), and six designed complexes. Similarly, Table 3 shows the energies of HOMO (EH), LUMO (EL) and energy gaps (Eg) of host, guests and the complexes. The red and green patches represent the positive and negative phases respectively. In the HOMO of bare CB[7], the patches are spread over all oxygen and nitrogen atoms, indicating that the electronic cloud is concentrated over there. The LUMO isodensities are spread mostly over the C and O atoms of the host. The EH, EL and Eg for CB[7] are − 6.71, -0.15 and 6.56 eV, respectively (comparable to already reported literature48). In benzophenone@CB[7] complex, both the HOMO and LUMO isodensities appear on the guest. The EH, EL and Eg for benzophenone@CB[7] are − 5.53, -0.59 and 4.94 eV, respectively after complexation. The Eg decreases after complexation as compared to bare host. This can be attributed to the increase in energy of HOMO and decrease in energy of LUMO after complexation, compared to bare host. Upon complexation, the HOMO energy increases significantly, ranging from − 5.53 to -4.64 eV for the guest@CB[7] complexes. Importantly, frontier molecular orbital analysis reveals that the HOMO of the complexes becomes predominantly localized on the guest molecules, indicating that the frontier orbitals are now governed by the electronic structure of the guest. This shift in orbital localization and energy reflects a redistribution of electron density upon complexation. Therefore, the increase in HOMO energy is therefore attributed to electronic interactions between the host and guest.

The HOMO isodensities for dioxybenzone@CB[7]complex are observed on guest (dioxybenzone) and LUMO on both the host and guest species (dioxybenzone and CB[7]). EH, EL and Eg for complex are − 4.68, -0.20 and 4.47 eV, respectively. Eg for the complex is decreased after complexation due to increase in energy of HOMO and decrease in energy of LUMO. Moreover, the HOMO and LUMO isodensities for homosalate@CB[7] and PABA@CB[7] are observed over the guest and host, respectively, whereas for oxybenzone@CB[7] and sulisobenzone@CB[7], both the HOMO and LUMO isodensities spread over the guest species. The Eg decreases for all the complexes after complexation when compared to the bare host CB7 (range from 4.37 to 4.88 eV). Overall, it is evident that in all the complexes, the values of EH increase and EL decreases. Thus, FMO analysis reveal the reasonable energy gaps, hence stability of the designed complexes.

DOS analysis

Total density of states (TDOS) and partial density of states (PDOS) analyses are performed so as to validate the positions and contribution of HOMO, and LUMO of host (CB[7]) and guests (benzophenone, dioxybenzone, homosalate, oxybenzone, PABA and sulisobenzone) towards the HOMO and LUMO of complexes. Moreover, the graphs of DOS effectively demonstrate the orbital characteristics in different energy ranges, each discrete line corresponds to a molecular orbital (MO). The curves are generated by applying broadening function to these discrete lines of MOs (y-axis). The only relative height of the curves is meaningful rather than the absolute height. The dotted line in Fig. 6 represent the HOMO level of the complexes. After HOMO, the first vertically upward line on x-axis is the position of LUMO. The black, red and blue curves in DOS maps represent the total density of states and partial density of states for host and guest, respectively. The graphs clearly exhibit the red and blue colored discrete lines pointing upwards on x-axis (representing MOs). The greater number of red lines compared to blue ones signify the greater contribution of the orbitals of CB[7] towards the MOs of the host-guest species for all the studied complexes. This results in the greater relative height of the red curves compared to blue ones. Hence, it can be concluded that the major composition of molecular orbitals comes from the host CB[7], compared to the guest species.

In benzophenone@CB[7] complex, the graphs of PDOS show that at HOMO level, the position of blue curve is dominant compared to red curve, which highlights the greater contribution of guest’s HOMO towards the HOMO of the corresponding complex. At LUMO position, the contribution of guest is observed along with the host (i.e., blue and red curves, respectively). Similarly, for PABA@CB[7] and sulisobenzone@CB[7], the molecular orbitals of the guests are contributing majorly towards the HOMO of the complexes, whereas the molecular orbitals of the host CB[7] are primarily responsible for LUMO for PABA@CB[7] complex. For the other three complexes, the contribution of HOMO of the host and LUMO of both the host and guests are observed for TDOS plot of the complexes, respectively. The region between the HOMO and LUMO in the space is energy gap. Most of the region in DOS maps do not show any curve or is vacant, as the host, guest as well as complexes have greater energy gaps ranging from 4.37 to 4.94 eV, which are interpreted via FMO analysis. Hence, DOS supports the findings of FMO by illustrating the positions and contribution of HOMO, LUMO and energy gaps of the host, guests and complexes.

NBO analysis

The direction of charge transfer from host to guest or vice versa is better examined via natural bond orbital (NBO) charge analysis. The net charge on all the atoms of the host and guest before complexation is zero, i.e., neutral species. The sign of the net NBO charge after complex formation describes the direction of charge transfer. If sum of charges on guest and host is negative and positive respectively, it indicates that the charge is accumulated from the host towards the guest specie. Conversely, if sum of charges on the guest and host is positive and negative, it reveals the NBO charge accumulation over the host and charge depletion from the guest specie. Table 3 reports the NBO charges on the guest species after complex formation. Here, NBO analysis predicts that after encapsulation of guest inside the host CB[7], the charge is transferred from CB[7] towards the guests in all the cases, which is revealed by the net negative charge on guest species in all the complexes. The range of NBO is -0.009 to -0.019|e|. The least NBO charge transfer is observed for benzophenone@CB[7] complex, i.e., -0.009|e|, indicating the comparatively lesser interactions and greater interaction distances, which are also justified via NCI, QTAIM and interaction energy analyses. Moreover, the other complexes show somewhat greater NBO charge due to the greater interactions comparatively. Overall, the charge is transferred from host towards guests in all the designed host-guest complexes.

EDD analysis

For the visualization of NBO charge transfer, electron density difference (EDD) analysis is performed. Figure 7 shows EDD isosurfaces for the most stable complexes. The blue and red isosurfaces represent the charge accumulation and depletion, respectively. For benzophenone@CB[7] complex, the greater blue isosurfaces spread over the guest compared to the host, indicating the greater charge accumulation over the guest benzophenone. Similarly, the greater blue isosurfaces are observed over dioxybenzone in dioxybenzone@CB[7] complex, compared to CB[7]. In comparison between the two complexes, it can be seen that the greater EDD isosurfaces are present over host and guest in dioxybenzone@CB[7], compared to benzophenone@CB[7]. This is actually a justification of NBO charge analysis where lesser charge transfer is observed for benzophenone@CB[7] complex. Similarly, for the other complexes, the greater blue isosurfaces spread over the guest species, representing the net charge accumulation over the guest species. Hence, the direction of net charge transfer predicted via NBO analysis is confirmed by EDD, i.e., host towards the guest specie.

Recovery time and desorption energies

The recovery times for the guests from host are calculated at 298, 350 and 400 K. Table 4 reports a decrease in recovery time with increase in temperature in all the cases, as high temperature provides greater energy for desorption. Conversely, recovery time increases with increase in interaction or adsorption energy (Eads). Similarly, desorption energy (Edes) also increases with increase in adsorption or interaction energy, i.e., greater energy is required to desorb a specie having higher interactions. The Eads for the complexes range from − 11.78 to -20.42 kcal/mol, and Edes range from 11.78 to 20.42 kcal/mol. The Eads, Edes and recovery time (τ) for benzophenone@CB[7] are lowest among all the complexes which means that it is easy to desorb benzophenone from CB[7]. The τ for benzophenone@CB[7] is 4.3\(\:\times\:\)10−4, 2.2\(\:\times\:\)10−5, and 2.7\(\:\times\:\)10−6 s, respectively at 298, 350 and 400 K. Moreover, the Eads, Edes and τ for dioxybenzone@CB[7] are highest among all the complexes, indicating the highest stability of dioxybenzone inside CB[7]. The τ for desorption of dioxybenzone from CB[7] at 298, 350 and 400 K are 9.3\(\:\times\:\)102, 5.6 and 1.4\(\:\times\:\)10−1 s, respectively. The desorption energies (Edes) for the designed complexes follow a trend i.e., dioxybenzone@CB[7] (20.42 kcal/mol) > sulisobenzone@CB[7](20.37 kcal/mol) > homosalate@CB[7] (19.21 kcal/mol) > oxybenzone@CB[7] (15.51 kcal/mol) > PABA@CB[7] (11.82 kcal/mol) > benzophenone@CB[7] (11.78 kcal/mol). The same trend is followed by recovery time, i.e., τ for dioxybenzone > sulisobenzone > homosalate > oxybenzone > PABA > benzophenone. Overall, it is observed that for all the complexes, recovery time decrease with increase in temperature and is highest for the complex having higher adsorption and desorption energies.

Reactivity descriptors

The chemical reactivity descriptors are computed for the designed complexes. The HOMO–LUMO energy gap (Eg) is often used as an indicator of a molecule’s electronic stability and chemical reactivity68. A larger energy gap typically suggests lower chemical reactivity and higher kinetic stability, while a smaller gap implies enhanced polarizability. All the designed host-guest complexes show reasonable energy gaps ranging from 4.37 to 4.94 eV, proving significant stability of the complexes. The energy gap between the frontier orbitals can be correlated with global descriptors such as chemical hardness and softness.

The hardness η is computed as

.

Here, \(\:I=\:-{E}_{HOMO\:}\)and \(\:A=-{E}_{LUMO}\), respectively. The softness of a molecule is determined as

.

These equations show that the molecules have greater values of chemical hardness compared to softness. Molecules with higher hardness are thermodynamically more stable, resisting deformation of their electron clouds upon interaction with external species. Thus, a greater Eg often translates to a more inert and stable system under ambient conditions.

The chemical potential, and electronegativity are computed via Eqs. (8) and (9), respectively.

The ionization energy of designed complexes range from 4.64 to 4.43 eV. The higher values of ionization energy exhibit the reasonable thermal stability of complexes. The electron affinity values are smaller, i.e., and range from 0.20 to 0.59 eV. Moreover, the compounds show significant electronegativity and chemical potential values. The values of the chemical reactivity descriptors are given in Table 5.

Conclusion

In this study, six host-guest encapsulated systems are designed by using CB[7] as host and benzophenone, homosalate, oxybenzone, dioxybenzone, sulisobenzone, and PABA as guests. DFT results suggest the thermodynamic stability of these designed systems, i.e., the interaction energies of the host-guest inclusion complexes range from − 11.78 to -20.42 kcal/mol. The NCI analysis explains that the host-guest complexes are stabilized through non-covalent interactions, which is further justified via QTAIM analysis. NCI illustrates the green colored isosurfaces in the surroundings of the guest, predicting the van der Waals interactions between the host and guest. The least number of BCPs in QTAIM are observed for benzophenone@CB[7] and PABA@CB[7], i.e., 17 and 16, respectively showing comparatively lesser interactions of these complexes with CB[7]. FMO analysis determines that for all the complexes, Eg decreases after complexation when compared to the bare host CB[7] and range from 4.37 to 4.88 eV. Additionally, it is evident in FMO that in all complexes, the values of EH increase and EL decreases. The calculation of chemical reactivity descriptors for the complexes shows that the molecules have greater values of chemical hardness compared to softness, as well as greater ionization energy, indicating reasonable thermodynamic stability. The studied compounds also show significant electronegativity and chemical potential. The DOS analysis supports the results of FMO analysis, providing visual illustration of the HOMO, LUMO levels and energy gaps. NBO analysis shows the net charge accumulation over the guests in all the complexes. Moreover, the greater NBO charge transfer is observed for oxybenzone@CB[7] complex, i.e., -0.019|e| whereas, the least for benzophenone@CB[7], i.e., -0.009|e|. The findings of NBO are validated by EDD via visual illustration of charge accumulation and depletion. Furthermore, the recovery time and desorption energy are highest for dioxybenzone, i.e., complex with highest adsorption energy, i.e., 9.3\(\:\times\:\)102 s (at 298 K) and 20.42 kcal/mol, respectively. The least recovery time is determined for benzophenone@belt complex, i.e., 2.7\(\:\times\:\)10−6 s at 400 K, i.e., complex with least adsorption energy. Hence, this study highlights that CB[7] exhibits a remarkable ability to encapsulate all these guest species effectively. Its performance underscores its suitability as a host molecule for complexation with organic UV filters, offering a reliable solution for their efficient removal from environment.

Data availability

Data Availability StatementThe data supporting this manuscript has been added in the supporting information file. In case of any additional concerns, corresponding author can be contacted at khurshid@cuiatd.edu.pk.

References

Tovar-Sánchez, A. et al. Sunscreen products as emerging pollutants to coastal waters. PLoS One. 8 (6), e65451 (2013).

Tovar-Sánchez, A., Sánchez-Ouiles, D., Basterretxea, G., Benedé, J. & Chisvert, A. Sunscreen Products as Emerging Pollutants to Coastal, (2013).

Chatzigianni, M. et al. Environmental impacts due to the use of sunscreen products: a mini-review, Ecotoxicology 31 (9), pp. 1331–1345, (2022).

Wheate, N. J. A review of environmental contamination and potential health impacts on aquatic life from the active chemicals in sunscreen formulations. Aust. J. Chem. 75 (4), 241–248 (2022).

Schneider, S. L. & Lim, H. W. Review of environmental effects of oxybenzone and other sunscreen active ingredients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 80 (1), 266–271 (2019).

Stiefel, C., Schwack, W. & Nguyen, Y. T. H. Photostability of cosmetic UV filters on mammalian skin under UV exposure. Photochem. Photobiol. 91 (1), 84–91 (2015).

Stiefel, C. & Schwack, W. Photoprotection in changing times–UV filter efficacy and safety, sensitization processes and regulatory aspects. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 37 (1), 2–30 (2015).

Sklar, L. R., Almutawa, F., Lim, H. W. & Hamzavi, I. Effects of ultraviolet radiation, visible light, and infrared radiation on erythema and pigmentation: a review. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 12, 54–64 (2012).

Battie, C. et al. New insights in photoaging, UVA induced damage and skin types, Experimental dermatology 23, 7–12. (2014).

Narayanan, D. L., Saladi, R. N. & Fox, J. L. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. Int. J. Dermatol. 49 (9), 978–986 (2010).

De Gruijl, F. Skin cancer and solar UV radiation. Eur. J. Cancer. 35 (14), 2003–2009 (1999).

Osterwalder, U. & Herzog, B. Sun protection factors: world wide confusion. Br. J. Dermatol. 161 (s3), 13–24 (2009).

Mao, J. F. et al. Assessment of human exposure to benzophenone-type UV filters: a review. Environ. Int. 167, 107405 (2022).

Mao, F., He, Y. & Gin, K. Y. H. Occurrence and fate of benzophenone-type UV filters in aquatic environments: a review. Environ. Science: Water Res. Technol. 5 (2), 209–223 (2019).

Tsoumachidou, S., Lambropoulou, D. & Poulios, I. Homogeneous photocatalytic oxidation of UV filter para-aminobenzoic acid in aqueous solutions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 1113–1121 (2017).

Ziklo, N., Tzafrir, I., Shulkin, R. & Salama, P. Salicylate UV-filters in sunscreen formulations compromise the preservative system efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia, Cosmetics 7 (3), 63. (2020).

Couteau, C., Paparis, E., Chauvet, C. & Coiffard, L. Tris-biphenyl triazine, a new ultraviolet filter studied in terms of photoprotective efficacy. Int. J. Pharm. 487, 1–2 (2015).

Gunia-Krzyżak, A. et al. Cinnamic acid derivatives in cosmetics: current use and future prospects. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 40 (4), 356–366 (2018).

Hubaud, J. C., Bombarda, I., Decome, L., Wallet, J. C. & Gaydou, E. M. Synthesis and spectroscopic examination of various substituted 1, 3-dibenzoylmethane, active agents for UVA/UVB photoprotection. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 92 (2), 103–109 (2008).

Anichina, K. K. & Georgiev, N. I. Synthesis of 2-Substituted Benzimidazole Derivatives as a Platform for the Development of UV Filters and Radical Scavengers in Sunscreens, Organics 4 (4), 524–538. (2023).

Holbech, H., Nørum, U., Korsgaard, B. & Bjerregaard, P. The chemical UV-filter 3‐benzylidene Camphor causes an oestrogenic effect in an in vivo fish assay. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 91 (4), 204–208 (2002).

Liu, Y. S., Ying, G. G., Shareef, A. & Kookana, R. S. Occurrence and removal of benzotriazoles and ultraviolet filters in a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Pollut. 165, 225–232 (2012).

Schneider, S. L. & Lim, H. W. A review of inorganic UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide. PhotoDermatol. PhotoImmunol. PhotoMed. 35 (6), 442–446 (2019).

Bennat Skin penetration and stabilization of formulations containing microfine titanium dioxide as physical UV filter. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 22 (4), 271–283 (2000).

Zhang, Q., Ma, X., Dzakpasu, M. & Wang, X. C. Evaluation of ecotoxicological effects of benzophenone UV filters: luminescent bacteria toxicity, genotoxicity and hormonal activity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 142, 338–347 (2017).

DiNardo, J. C. & Downs, C. A. Dermatological and environmental toxicological impact of the sunscreen ingredient oxybenzone/benzophenone-3. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 17 (1), 15–19 (2018).

Erol, M. et al. Evaluation of the endocrine-disrupting effects of homosalate (HMS) and 2-ethylhexyl 4-dimethylaminobenzoate (OD-PABA) in rat pups during the prenatal, lactation, and early postnatal periods. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 33 (10), 775–791 (2017).

Rathi, B. S., Kumar, P. S. & Vo, D. V. N. Critical review on hazardous pollutants in water environment: occurrence, monitoring, fate, removal technologies and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 797, 149134 (2021).

Shah, B. R. & Patel, U. D. Aqueous pollutants in water bodies can be photocatalytically reduced by TiO2 nano-particles in the presence of natural organic matters. Sep. Purif. Technol. 209, 748–755 (2019).

Delgado, L. F., Charles, P., Glucina, K. & Morlay, C. The removal of endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceutically activated compounds and cyanobacterial toxins during drinking water Preparation using activated carbon—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 435, 509–525 (2012).

Ugwu, E. I. et al. Application of green nanocomposites in removal of toxic chemicals, heavy metals, radioactive materials, and pesticides from aquatic water bodies. in Sustainable Nanotechnology for Environmental Remediation (eds Bandala, E. R. et al.) 321–346 (Elsevier, 2022).

Li, W. et al. Occurrence and behavior of four of the most used sunscreen UV filters in a wastewater reclamation plant. Water Res. 41 (15), 3506–3512 (2007).

Belgacem, C. et al. Synthesis of ultramicroporous zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-8 via solid state method using a minimum amount of deionized water for high greenhouse gas adsorption: a computational modeling. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12 (2), 112086 (2024).

Missaoui, N. et al. Synergistic combination of experimental and theoretical studies on chlorinated volatile organic compound adsorption in highly microporous n-MOF-5 and amino-substituted n-MOF-5-NH2 nanocrystals synthesized via PEG soft-templating. J. Mol. Liq. 418, 126716 (2025).

Chérif, I. et al. A theoretical and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study of the adsorption and sensing of selected metal ions by 4-morpholino-7-nitrobenzofuran, Heliyon 10 (5), (2024).

Tsui, M. M., Leung, H., Lam, P. K. & Murphy, M. B. Seasonal occurrence, removal efficiencies and preliminary risk assessment of multiple classes of organic UV filters in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 53, 58–67 (2014).

Krzeminski, P., Schwermer, C., Wennberg, A., Langford, K. & Vogelsang, C. Occurrence of UV filters, fragrances and organophosphate flame retardants in municipal WWTP effluents and their removal during membrane post-treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 323, 166–176 (2017).

Surana, D., Gupta, J., Sharma, S., Kumar, S. & Ghosh, P. A review on advances in removal of endocrine disrupting compounds from aquatic matrices: future perspectives on utilization of agri-waste based adsorbents. Sci. Total Environ. 826, 154129 (2022).

Gago-Ferrero, P. et al. Evaluation of fungal-and photo-degradation as potential treatments for the removal of sunscreens BP3 and BP1. Sci. Total Environ. 427, 355–363 (2012).

Nguyen, L. N. et al. Removal of pharmaceuticals, steroid hormones, phytoestrogens, UV-filters, industrial chemicals and pesticides by trametes versicolor: role of biosorption and biodegradation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 88, 169–175 (2014).

Celeiro, M., Hackbarth, F. V., de Souza, S. M. G. U., Llompart, M. & Vilar, V. J. Assessment of advanced oxidation processes for the degradation of three UV filters from swimming pool water. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 351, 95–107 (2018).

Selinger, A. J. & Macartney, D. H. Cucurbit [7] uril complexations of good’s buffers. RSC Adv. 7 (67), 42513–42518 (2017).

Mustafa, S. F. Z., Arsad, S. R., Mohamad, H., Abdallah, H. H. & Maarof, H. Host-guest molecular encapsulation of cucurbit [7] uril with dillapiole congeners using docking simulation and density functional theory approaches, Structural Chemistry 32, pp. 1151–1161, (2021).

Maqbool, M. et al. Finely tuned energy gaps in host-guest complexes: insights from belt [14] pyridine and fullerene-based nano-Saturn systems. Diam. Relat. Mater. 150, 111686 (2024).

Maqbool, M., Aetizaz, M. & Ayub, K. Chiral discrimination of amino acids by möbius carbon belt. Diam. Relat. Mater. 146, 111227 (2024).

Maqbool, M. & Ayub, K. Controlled tuning of HOMO and LUMO levels in supramolecular nano-Saturn complexes. RSC Adv. 14 (53), 39395–39407 (2024).

Maqbool, M. & Ayub, K. Chiral recognition of amino acids through homochiral metallacycle [ZnCl 2 L] 2. Biomaterials Sci. 13 (1), 310–323 (2025).

Venkataramanan, N. S., Suvitha, A. & Kawazoe, Y. Unravelling the nature of binding of Cubane and substituted Cubanes within cucurbiturils: A DFT and NCI study. J. Mol. Liq. 260, 18–29 (2018).

Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Becker, U. & Riplinger, C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 224108 (2020).

Lin, Y. S., Li, G. D., Mao, S. P. & Chai, J. D. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with improved dispersion corrections. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9 (1), 263–272 (2013).

Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split Valence, triple zeta Valence and quadruple zeta Valence quality for H to rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7 (18), 3297–3305 (2005).

Aetizaz, M., Ullah, F., Mahmood, T. & Ayub, K. Investigating the sensing efficiency of C6O6Li6 for detecting lung cancer-related volatile organic compounds: A computational density functional theory approach. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1232, 114469 (2024).

Klyukin, I. N., Kolbunova, A. V., Novikov, A. S., Zhizhin, K. Y. & Kuznetsov, N. T. Theoretical investigation of bond dissociation energies of exo-Polyhedral B–H and B–F bonds of closo-Borate anions [BnHn – 1X] 2–. Computation 13 (2), 28 (2025). (n = 6, 10, 12; X = H, F),.

Zhurko, G. Chemcraft: http://www.chemcraftprog.com. Received October 22 (2014).

Dennington, R., Keith, T., Millam, J. & GaussView, V. Shawnee Mission KS GaussView Version 5 (2009).

Lu, L., Zhu, S., Zhang, H., Li, F. & Zhang, S. Theoretical study of complexation of Resveratrol with cyclodextrins and cucurbiturils: structure and antioxidative activity. RSC Adv. 5 (19), 14114–14122 (2015).

Venkataramanan, N. S., Suvitha, A. & Sahara, R. Structure, stability, and nature of bonding between high energy water clusters confined inside cucurbituril: A computational study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1148, 44–54 (2019).

Pichierri, F. Density functional study of cucurbituril and its sulfur analogue. Chem. Phys. Lett. 390, 1–3 (2004).

Rosa, N. M. & Borges, I. Jr Star-shaped molecules with a triazine Core:(TD) DFT investigation of charge transfer and photovoltaic properties of organic solar cells. Braz. J. Phys. 54 (6), 252 (2024).

Glendening, E. et al. Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison (2018).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33 (5), 580–592 (2012).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14 (1), 33–38 (1996). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0263785596000185

J. Contreras-García, R. A. Boto, F. Izquierdo-Ruiz, I. Reva, T. Woller, and M. Alonso,A benchmark for the non-covalent interaction (NCI) index or… is it really all in the geometry? Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 135, 1–14, 2016.

Forni, A., Pieraccini, S., Franchini, D. & Sironi, M. Assessment of Dft functionals for Qtaim topological analysis of halogen bonds with benzene. J. Phys. Chem. A. 120 (45), 9071–9080 (2016).

Mohanty, B., Suvitha, A. & Venkataramanan, N. S. Piperine encapsulation within cucurbit [n] uril (n = 6, 7): a combined experimental and density functional study, ChemistrySelect 3 (6), 1933–1941. (2018).

Hasanzade, Z. & Raissi, H. Molecular mechanism for the encapsulation of the doxorubicin in the cucurbit [n] urils cavity and the effects of diameter, protonation on loading and releasing of the anticancer drug: mixed quantum mechanical/molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 196, 105563 (2020).

Shewale, M. N., Lande, D. N. & Gejji, S. P. Encapsulation of benzimidazole derivatives within cucurbit [7] uril: density functional investigations. J. Mol. Liq. 216, 309–317 (2016).

Choudhary, V., Bhatt, A., Dash, D. & Sharma, N. DFT calculations on molecular structures, HOMO–LUMO study, reactivity descriptors and spectral analyses of newly synthesized Diorganotin (IV) 2-chloridophenylacetohydroxamate complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 40 (27), 2354–2363 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU250179].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Faizan Ullah and Maria Maqbool wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ullah, F., Maqbool, M., Sheikh, N.S. et al. Scavenging sunblock agents from aquatic environment through encapsulation in cucurbit[7]uril. Sci Rep 15, 29386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10388-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10388-1